Dynamics of Gut Microbiota in Japanese Tits (Parus minor) Across Developmental Stages: Composition, Diversity, and Associations with Body Condition

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Sample Collection

2.2. Sex Identification

2.3. DNA Extractions from Feces

2.4. Illumina MiSeq Sequencing

2.5. Bioinformatics

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

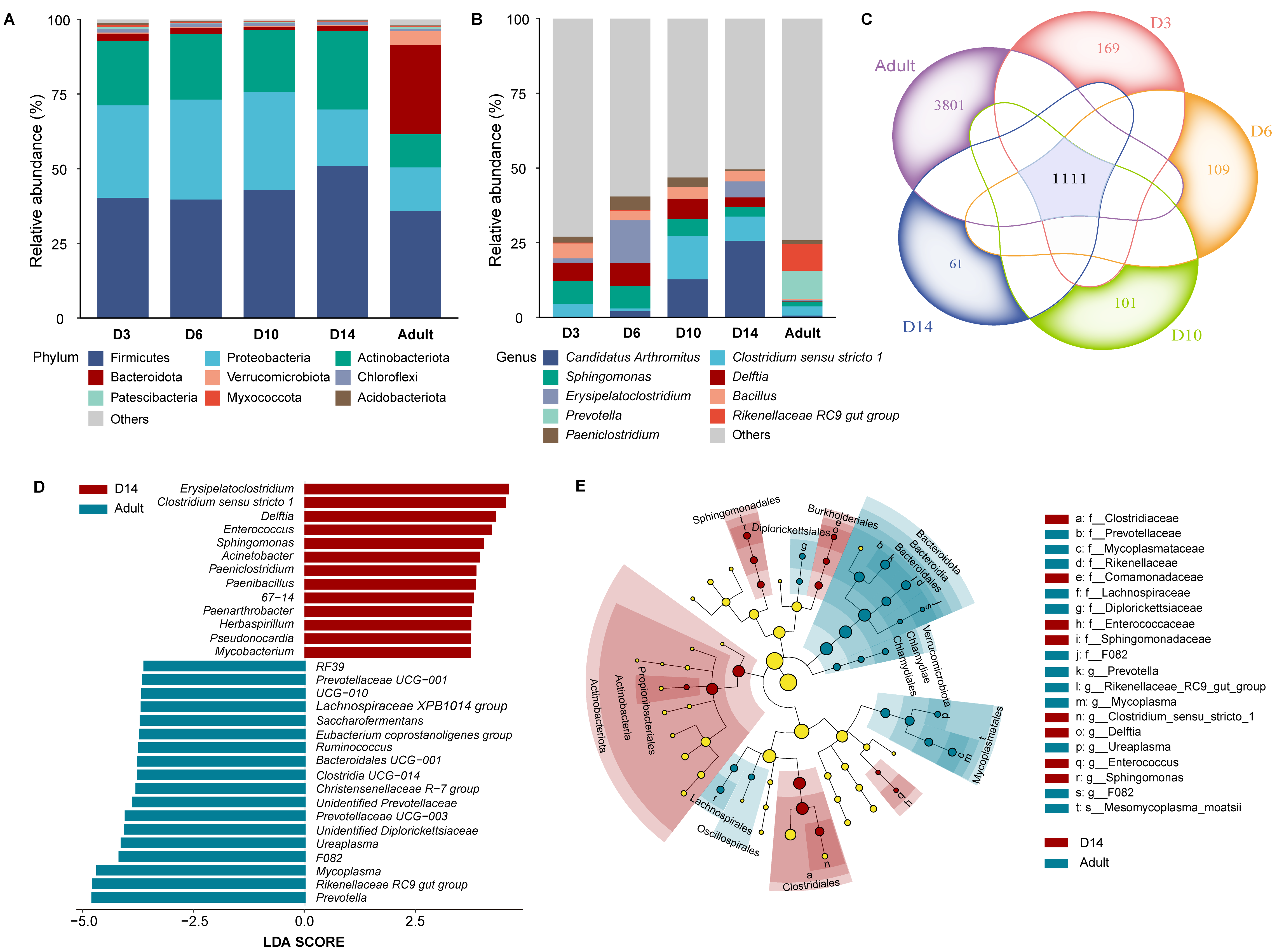

3.1. Gut Microbiota Composition

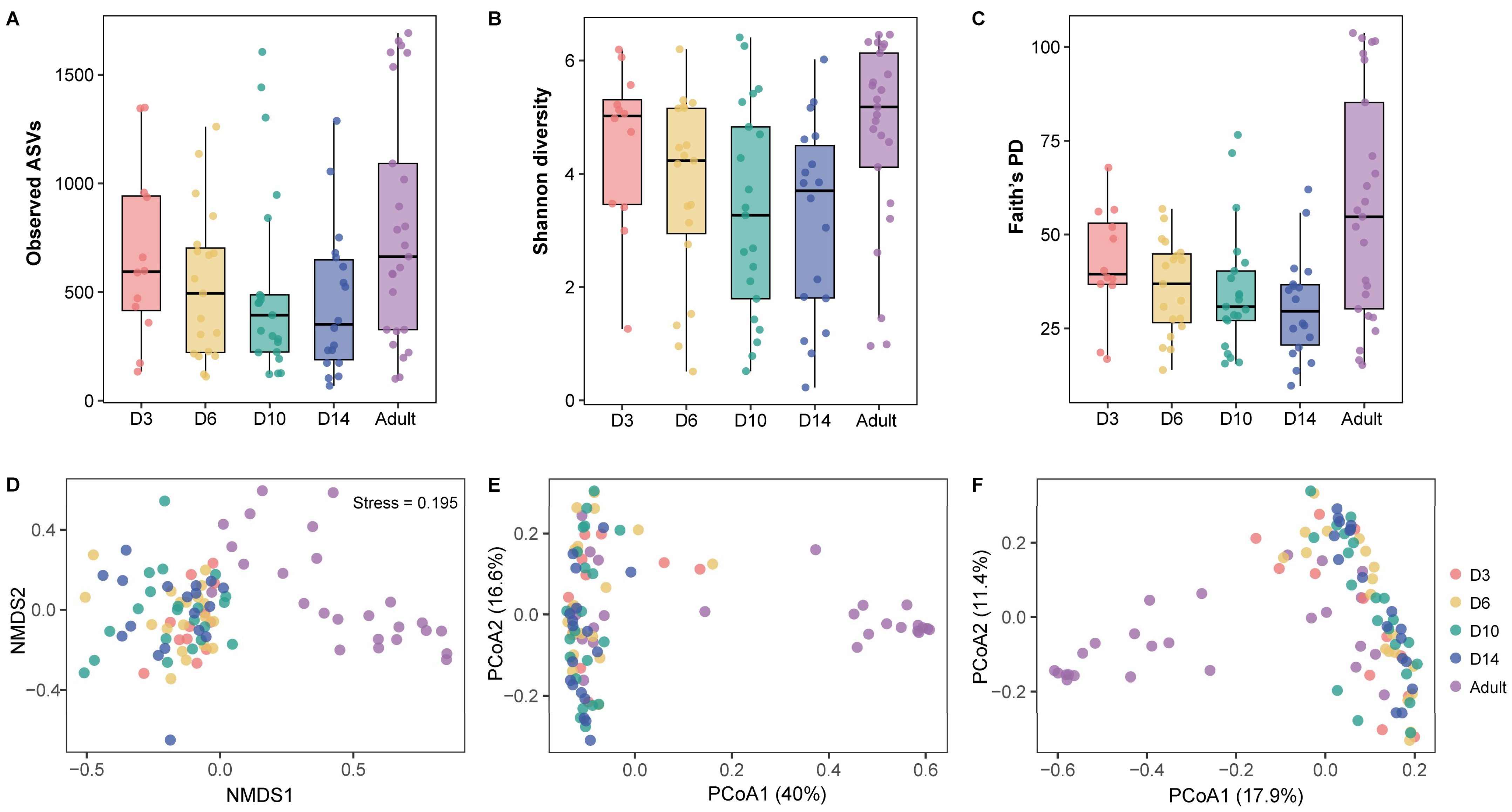

3.2. Alpha Diversity

3.3. Beta Diversity

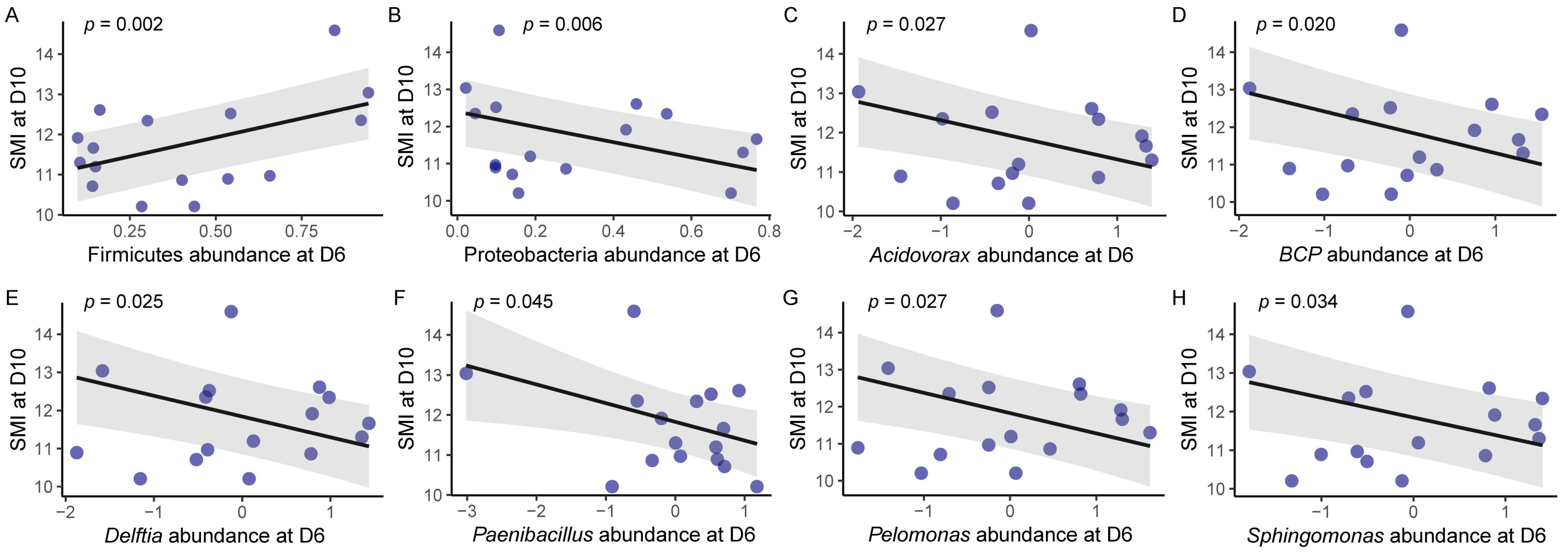

3.4. Gut Microbiota and the SMI of Hosts

4. Discussion

4.1. Composition and Dynamics of Gut Microbiota

4.2. Age-Related Changes in Gut Microbiota Diversity

4.3. Nest and Sex Effects on Gut Microbiota

4.4. Gut Microbiota and Body Condition

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- O’Hara, A.M.; Shanahan, F. The gut flora as a forgotten organ. Embo Rep. 2006, 7, 688–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Browne, H.P.; Neville, B.A.; Forster, S.C.; Lawley, T.D. Transmission of the gut microbiota: Spreading of health. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2017, 15, 531–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gould, A.L.; Zhang, V.; Lamberti, L.; Jones, E.W.; Obadia, B.; Korasidis, N.; Gavryushkin, A.; Carlson, J.M.; Beerenwinkel, N.; Ludington, W.B. Microbiome interactions shape host fitness. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, E11951–E11960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clemente, J.C.; Ursell, L.K.; Parfrey, L.W.; Knight, R. The impact of the gut microbiota on human health: An integrative view. Cell 2012, 148, 1258–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Liang, X.; Lei, C.; Huang, Q.; Song, W.; Fang, R.; Li, C.; Li, X.; Mo, H.; Sun, N.; et al. High-fat diet affects heavy metal accumulation and toxicity to mice liver and kidney probably via gut microbiota. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, K.; Baptista, A.P.; Tamoutounour, S.; Zhuang, L.; Bouladoux, N.; Martins, A.J.; Huang, Y.; Gerner, M.Y.; Belkaid, Y.; Germain, R.N. Innate and adaptive lymphocytes sequentially shape the gut microbiota and lipid metabolism. Nature 2018, 554, 255–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belkaid, Y.; Hand, T.W. Role of the microbiota in immunity and inflammation. Cell 2014, 157, 121–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gensollen, T.; Iyer, S.S.; Kasper, D.L.; Blumberg, R.S. How colonization by microbiota in early life shapes the immune system. Science 2016, 352, 539–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherwin, E.; Bordenstein, S.R.; Quinn, J.L.; Dinan, T.G.; Cryan, J.F. Microbiota and the social brain. Science 2019, 366, 587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.M.; Nassar, N.; Chang, H.; Khan, S.; Cheng, M.J.; Wang, Z.G.; Xiang, X. The microbiota: A key regulator of health, productivity, and reproductive success in mammals. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1480811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, S.; Chen, T.; Lu, Z.; Zhao, W.; Mou, X.; Liu, S. Consistent signatures in the human gut microbiome of longevous populations. Gut Microbes 2024, 16, 2393756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kohl, K.D.; Carey, H.V. A place for host-microbe symbiosis in the comparative physiologist’s toolbox. J. Exp. Biol. 2016, 219, 3496–3504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- David, L.A.; Maurice, C.F.; Carmody, R.N.; Gootenberg, D.B.; Button, J.E.; Wolfe, B.E.; Ling, A.V.; Devlin, A.S.; Varma, Y.; Fischbach, M.A.; et al. Diet rapidly and reproducibly alters the human gut microbiome. Nature 2014, 505, 559–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frese, S.A.; Parker, K.; Calvert, C.C.; Mills, D.A. Diet shapes the gut microbiome of pigs during nursing and weaning. Microbiome 2015, 3, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.Y.; Peralta-Sánchez, J.M.; Martínez-Bueno, M.; Moller, A.P.; Rabelo-Ruiz, M.; Zamora-Muñoz, C.; Soler, J.J. The gut microbiota of brood parasite and host nestlings reared within the same environment: Disentangling genetic and environmental effects. ISME J. 2020, 14, 2691–2702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grieneisen, L.; Dasari, M.; Gould, T.J.; Björk, J.R.; Grenier, J.-C.; Yotova, V.; Jansen, D.; Gottel, N.; Gordon, J.B.; Learn, N.H.; et al. Gut microbiome heritability is nearly universal but environmentally contingent. Science 2021, 373, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, J.A. Social behavior and the microbiome. Elife 2015, 4, e07322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moeller, A.H.; Foerster, S.; Wilson, M.L.; Pusey, A.E.; Hahn, B.H.; Ochman, H. Social behavior shapes the chimpanzee pan-microbiome. Sci. Adv. 2016, 2, e1500997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, J.B.; Vangay, P.; Huang, H.; Ward, T.; Hillmann, B.M.; Al-Ghalith, G.A.; Travis, D.A.; Long, H.T.; Van Tuan, B.; Van Minh, V.; et al. Captivity humanizes the primate microbiome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 10376–10381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baniel, A.; Amato, K.R.; Beehner, J.C.; Bergman, T.J.; Mercer, A.; Perlman, R.F.; Petrullo, L.; Reitsema, L.; Sams, S.; Lu, A.; et al. Seasonal shifts in the gut microbiome indicate plastic responses to diet in wild geladas. Microbiome 2021, 9, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenig, J.E.; Spor, A.; Scalfone, N.; Fricker, A.D.; Stombaugh, J.; Knight, R.; Angenent, L.T.; Ley, R.E. Succession of microbial consortia in the developing infant gut microbiome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 4578–4585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janiak, M.C.; Montague, M.J.; Villamil, C.I.; Stock, M.K.; Trujillo, A.E.; DePasquale, A.N.; Orkin, J.D.; Bauman Surratt, S.E.; Gonzalez, O.; Platt, M.L.; et al. Age and sex-associated variation in the multi-site microbiome of an entire social group of free-ranging rhesus macaques. Microbiome 2021, 9, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox, L.M.; Yamanishi, S.; Sohn, J.; Alekseyenko, A.V.; Leung, J.M.; Cho, I.; Kim, S.G.; Li, H.; Gao, Z.; Mahana, D.; et al. Altering the intestinal microbiota during a critical developmental window has lasting metabolic consequences. Cell 2014, 158, 705–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pascoe, E.L.; Hauffe, H.C.; Marchesi, J.R.; Perkins, S.E. Network analysis of gut microbiota literature: An overview of the research landscape in non-human animal studies. ISME J. 2017, 11, 2644–2651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kohl, K.D. Diversity and function of the avian gut microbiota. J. Comp. Physiol. B 2012, 182, 591–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.Y.; Chen, C.K.; Chen, Y.Y.; Fang, A.; Shaw, G.T.W.; Hung, C.M.; Wang, D. Maternal gut microbes shape the early-life assembly of gut microbiota in passerine chicks via nests. Microbiome 2020, 8, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grond, K.; Sandercock, B.K.; Jumpponen, A.; Zeglin, L.H. The avian gut microbiota: Community, physiology and function in wild birds. J. Avian Biol. 2018, 49, e01788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dongen, W.F.; White, J.; Brandl, H.B.; Moodley, Y.; Merkling, T.; Leclaire, S.; Blanchard, P.; Danchin, É.A.; Hatch, S.; Wagner, R.H. Age-related differences in the cloacal microbiota of a wild bird species. BMC Ecol. 2013, 13, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teyssier, A.; Lens, L.; Matthysen, E.; White, J. Dynamics of gut microbiota diversity during the early development of an avian host: Evidence from a cross-foster experiment. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohl, K.D.; Brun, A.; Caviedes-Vidal, E.; Karasov, W.H. Age-related changes in the gut microbiota of wild house sparrow nestlings. Ibis 2019, 161, 184–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Huo, X.A.; Liu, B.Y.; Wu, H.; Feng, J. Comparative analysis of the gut microbial communities of the eurasian kestrel (Falco tinnunculus) at different developmental stages. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 592539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dewar, M.L.; Arnould, J.P.Y.; Allnutt, T.R.; Crowley, T.; Krause, L.; Reynolds, J.; Dann, P.; Smith, S.C. Microbiota of little penguins and short-tailed shearwaters during development. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0183117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Videvall, E.; Song, S.J.; Bensch, H.M.; Strandh, M.; Engelbrecht, A.; Serfontein, N.; Hellgren, O.; Olivier, A.; Cloete, S.; Knight, R.; et al. Major shifts in gut microbiota during development and its relationship to growth in ostriches. Mol. Ecol. 2019, 28, 2653–2667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Y.Z.; Wang, J.M.; Shi, L.Y.; Sun, H.Y.; Cheng, B.X.; Sun, Y. Adaptive characteristics of the gut microbiota of the scaly-sided merganser (Mergus squamatus) in energy compensation at different developmental stages. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1614319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maraci, Ö.; Antonatou-Papaioannou, A.; Jünemann, S.; Engel, K.; Castillo-Gutiérrez, O.; Busche, T.; Kalinowski, J.; Caspers, B.A. Timing matters: Age-dependent impacts of the social environment and host selection on the avian gut microbiota. Microbiome 2022, 10, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberdi, A.; Aizpurua, O.; Bohmann, K.; Zepeda-Mendoza, M.L.; Gilbert, M.T.P. Do vertebrate gut metagenomes confer rapid ecological adaptation? Trends Ecol. Evol. 2016, 31, 689–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, L.R.; Zhang, P.; Sun, K.P.; Wang, H.T. Gut microbiota dynamics and their impact on body condition in nestlings of the yellow-rumped flycatchers, Ficedula zanthopygia. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1595357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, G.L.; Somers, S.E.; Wiley, N.; Johnson, C.N.; Reichert, M.S.; Ross, R.P.; Stanton, C.; Quinn, J.L. A time-lagged association between the gut microbiome, nestling weight and nestling survival in wild great tits. J. Anim Ecol. 2021, 90, 989–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozupone, C.A.; Stombaugh, J.I.; Gordon, J.I.; Jansson, J.K.; Knight, R. Diversity, stability and resilience of the human gut microbiota. Nature 2012, 489, 220–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaumont, M.; Goodrich, J.K.; Jackson, M.A.; Yet, I.; Davenport, E.R.; Vieira-Silva, S.; Debelius, J.; Pallister, T.; Mangino, M.; Raes, J.; et al. Heritable components of the human fecal microbiome are associated with visceral fat. Genome Biol. 2016, 17, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Chatelier, E.; Nielsen, T.; Qin, J.; Prifti, E.; Hildebrand, F.; Falony, G.; Almeida, M.; Arumugam, M.; Batto, J.-M.; Kennedy, S.; et al. Richness of human gut microbiome correlates with metabolic markers. Nature 2013, 500, 541–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drissi, F.; Raoult, D.; Merhej, V. Metabolic role of lactobacilli in weight modification in humans and animals. Microb. Pathog. 2017, 106, 182–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- E, M.; Shen, C.; Bibi, N.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, L.; Li, X. The influence of body condition and personality on nest defense behavior of japanese tits (Parus minor). Anim. Cogn. 2025, 28, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peig, J.; Green, A.J. New perspectives for estimating body condition from mass/length data: The scaled mass index as an alternative method. Oikos 2009, 118, 1883–1891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Liu, Z.Y.; Sun, K.P.; Jin, L.R.; Yu, J.P.; Wang, H.T. Multi-dimensional niche differentiation of two sympatric breeding secondary cave-nesting birds in northeast china using DNA metabarcoding. Ecol. Evol. 2024, 14, e11709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magoc, T.; Salzberg, S.L. Flash: Fast length adjustment of short reads to improve genome assemblies. Bioinformatics 2011, 27, 2957–2963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.F.; Zhou, Y.Q.; Chen, Y.R.; Gu, J. Fastp: An ultra-fast all-in-one fastq preprocessor. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, 884–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolyen, E.; Rideout, J.R.; Dillon, M.R.; Bokulich, N.A.; Abnet, C.C.; Al-Ghalith, G.A.; Alexander, H.; Alm, E.J.; Arumugam, M.; Asnicar, F.; et al. Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science using qiime 2. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 852–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amir, A.; McDonald, D.; Navas-Molina, J.A.; Kopylova, E.; Morton, J.T.; Zech Xu, Z.; Kightley, E.P.; Thompson, L.R.; Hyde, E.R.; Gonzalez, A.; et al. Deblur rapidly resolves single-nucleotide community sequence patterns. Msystems 2017, 2, e00191–00116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bokulich, N.A.; Kaehler, B.D.; Rideout, J.R.; Dillon, M.; Bolyen, E.; Knight, R.; Huttley, G.A.; Gregory Caporaso, J. Optimizing taxonomic classification of marker-gene amplicon sequences with qiime 2′s q2-feature-classifier plugin. Microbiome 2018, 6, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMurdie, P.J.; Holmes, S. Phyloseq: An r package for reproducible interactive analysis and graphics of microbiome census data. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e61217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, M.N.; Dehal, P.S.; Arkin, A.P. Fasttree: Computing large minimum evolution trees with profiles instead of a distance matrix. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2009, 26, 1641–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wickham, H. Ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, C.H.; Yu, G.C.; Cai, P. Ggvenndiagram: An intuitive, easy-to-use, and highly customizable r package to generate venn diagram. Front. Genet. 2021, 12, 706907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benjamini, Y.; Hochberg, Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B 1995, 57, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segata, N.; Izard, J.; Waldron, L.; Gevers, D.; Miropolsky, L.; Garrett, W.S.; Huttenhower, C. Metagenomic biomarker discovery and explanation. Genome Biol. 2011, 12, R60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holman, D.B.; Brunelle, B.W.; Trachsel, J.; Allen, H.K. Meta-analysis to define a core microbiota in the swine gut. Msystems 2017, 2, e00004–00017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bender, R.; Lange, S. Adjusting for multiple testing—When and how? J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2001, 54, 343–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranstam, J. Hypothesis-generating and confirmatory studies, bonferroni correction, and pre-specification of trial endpoints. Acta Orthop. 2019, 90, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsui, H.; Kato, Y.; Chikaraishi, T.; Moritani, M.; Ban-Tokuda, T.; Wakita, M. Microbial diversity in ostrich ceca as revealed by 16s ribosomal RNA gene clone library and detection of novel fibrobacter species. Anaerobe 2010, 16, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.; Lee, W.Y. Interspecific comparison of the fecal microbiota structure in three arctic migratory bird species. Ecol. Evol. 2020, 10, 5582–5594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waite, D.W.; Taylor, M.W. Characterizing the avian gut microbiota: Membership, driving influences, and potential function. Front. Microbiol. 2014, 5, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janssen, P.H. Identifying the dominant soil bacterial taxa in libraries of 16s rrna and 16s rRNA genes. Appl. Environ. Microb. 2006, 72, 1719–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barka, E.A.; Vatsa, P.; Sanchez, L.; Gaveau-Vaillant, N.; Jacquard, C.; Meier-Kolthoff, J.P.; Klenk, H.-P.; Clément, C.; Ouhdouch, Y.; van Wezel, G.P. Taxonomy, physiology, and natural products of actinobacteria. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2016, 80, 1–43, Erratum in Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2016, 80, iii. https://doi.org/10.1128/Mmbr.00044-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Zheng, S.; Sharshov, K.; Sun, H.; Yang, F.; Wang, X.; Li, L.; Xiao, Z. Metagenomic profiling of gut microbial communities in both wild and artificially reared bar-headed goose (Anser indicus). Microbiologyopen 2017, 6, e00429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Q.; Cui, L.Y.; Hu, Z.F.; Du, X.P.; Abid, H.M.; Wang, H.B. Environmental and host factors shaping the gut microbiota diversity of brown frog Rana dybowskii. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 741, 140142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremaroli, V.; Bäckhed, F. Functional interactions between the gut microbiota and host metabolism. Nature 2012, 489, 242–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, C.; Zhang, L.; Jia, S.; Tang, X.; Fu, H.; Li, W.; Liu, C.; Zhang, H.; Cheng, Q.; Zhang, Y. Seasonal variations in the composition and functional profiles of gut microbiota reflect dietary changes in plateau pikas. Integr. Zool. 2022, 17, 379–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grond, K.; Lanctot, R.B.; Jumpponen, A.; Sandercock, B.K. Recruitment and establishment of the gut microbiome in arctic shorebirds. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2017, 93, fix142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, J.J.; Cao, H.Q.; Bao, X.Y.; Hu, C.S. Does nest occupancy by birds influence the microbial composition? Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1232208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, F.F.; Chen, J.F.; Liu, K.; Tang, M.Z.; Yang, Y.W. The avian gut microbiota: Diversity, influencing factors, and future directions. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 934272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, C.; Bik, E.M.; DiGiulio, D.B.; Relman, D.A.; Brown, P.O. Development of the human infant intestinal microbiota. PLoS Biol. 2007, 5, 1556–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costello, E.K.; Stagaman, K.; Dethlefsen, L.; Bohannan, B.J.M.; Relman, D.A. The application of ecological theory toward an understanding of the human microbiome. Science 2012, 336, 1255–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stecher, B.; Hardt, W.D. Mechanisms controlling pathogen colonization of the gut. Curr. Opin. Microbiol 2011, 14, 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hecht, A.L.; Casterline, B.W.; Earley, Z.M.; Goo, Y.A.; Goodlett, D.R.; Wardenburg, J.B. Strain competition restricts colonization of an enteric pathogen and prevents colitis. Embo Rep. 2016, 17, 1281–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brzek, P.; Kohl, K.; Caviedes-Vidal, E.; Karasov, W.H. Developmental adjustments of house sparrow (Passer domesticus) nestlings to diet composition. J. Exp. Biol. 2009, 212, 1284–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caviedes-Vidal, E.; Karasov, W.H. Developmental changes in digestive physiology of nestling house sparrows, Passer domesticus. Physiol. Biochem. Zool. 2001, 74, 769–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killpack, T.L.; Oguchi, Y.; Karasov, W.H. Ontogenetic patterns of constitutive immune parameters in altricial house sparrows. J. Avian Bio.l 2013, 44, 513–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godoy-Vitorino, F.; Goldfarb, K.C.; Brodie, E.L.; Garcia-Amado, M.A.; Michelangeli, F.; Domínguez-Bello, M.G. Developmental microbial ecology of the crop of the folivorous hoatzin. Isme J. 2010, 4, 611–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzmina, I.V. The yolk sac as the main organ in the early stages of animal embryonic development. Front. Physiol. 2023, 14, 1185286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlowski, G.; Frankiewicz, J.; Karg, J. Nestling diet optimization and condition in relation to prey attributes and breeding patch size in a patch-resident insectivorous passerine: An optimal continuum and habitat constraints. J. Ornithol. 2017, 158, 169–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Navas, V.; Ferrer, E.S.; Sanz, J.J. Prey selectivity and parental feeding rates of blue tits Cyanistes caeruleus in relation to nestling age. Bird Study 2012, 59, 236–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dion-Phénix, H.; Charmantier, A.; de Franceschi, C.; Bourret, G.; Kembel, S.W.; Réale, D. Bacterial microbiota similarity between predators and prey in a blue tit trophic network. Isme J. 2021, 15, 1098–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacob, S.; Parthuisot, N.; Vallat, A.; Ramon-Portugal, F.; Helfenstein, F.; Heeb, P. Microbiome affects egg carotenoid investment, nestling development and adult oxidative costs of reproduction in great tits. Funct. Ecol. 2015, 29, 1048–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodenough, A.E.; Stallwood, B.; Dandy, S.; Nicholson, T.E.; Stubbs, H.; Coker, D.G. Like mother like nest: Similarity in microbial communities of adult female pied flycatchers and their nests. J. Ornithol. 2017, 158, 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devaynes, A.; Antunes, A.; Bedford, A.; Ashton, P. Progression in the bacterial load during the breeding season in nest boxes occupied by the blue tit and its potential impact on hatching or fledging success. J. Ornithol. 2018, 159, 1009–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.W.; McKelvey, J.; Rollins, D.; Zhang, M.; Brightsmith, D.J.; Derr, J.; Zhang, S.P. Cultivable bacterial microbiota of northern bobwhite (Colinus virginianus): A new reservoir of antimicrobial resistance? PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e99826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohl, K.D.; Brun, A.; Bordenstein, S.R.; Caviedes-Vidal, E.; Karasov, W.H. Gut microbes limit growth in house sparrow nestlings (Passer domesticus) but not through limitations in digestive capacity. Integr. Zool. 2018, 13, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, H.; Chakarov, N.; Hoffman, J.I.; Rinaud, T.; Ottensmann, M.; Gladow, K.-P.; Tobias, B.; Caspers, B.A.; Maraci, Ö.; Krüger, O. Early-life factors shaping the gut microbiota of common buzzard nestlings. Anim. Microbiome 2024, 6, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turnbaugh, P.J.; Ley, R.E.; Mahowald, M.A.; Magrini, V.; Mardis, E.R.; Gordon, J.I. An obesity-associated gut microbiome with increased capacity for energy harvest. Nature 2006, 444, 1027–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, N.R.; Whon, T.W.; Bae, J.W. Proteobacteria: Microbial signature of dysbiosis in gut microbiota. Trends Biotechnol. 2015, 33, 496–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, C.H.F.; Nielsen, D.S.; Kverka, M.; Zakostelska, Z.; Klimesova, K.; Hudcovic, T.; Tlaskalova-Hogenova, H.; Hansen, A.K. Patterns of early gut colonization shape future immune responses of the host. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e34043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudo, N.; Chida, Y.; Aiba, Y.; Sonoda, J.; Oyama, N.; Yu, X.; Kubo, C.; Koga, Y. Postnatal microbial colonization programs the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal system for stress response in mice. J. Physiol. 2004, 558, 263–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirschman, L.J.; Khadjinova, A.; Ireland, K.; Milligan-Myhre, K.C. Early life disruption of the microbiota affects organ development and cytokine gene expression in threespine stickleback. Integr. Comp. Biol. 2023, 63, 250–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Distance Matrix | Variable | df | R2 | F Value | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bray–Curtis | age | 4 | 0.123 | 3.59 | 0.001 * |

| sex | 1 | 0.010 | 1.20 | 0.188 | |

| nest | 21 | 0.285 | 1.59 | 0.001 * | |

| Weighted UniFrac | age | 4 | 0.241 | 9.86 | 0.001 * |

| sex | 1 | 0.007 | 1.12 | 0.315 | |

| nest | 21 | 0.335 | 2.61 | 0.001 * | |

| Unweighted UniFrac | age | 4 | 0.139 | 4.18 | 0.001 * |

| sex | 1 | 0.007 | 0.86 | 0.621 | |

| nest | 21 | 0.287 | 1.64 | 0.001 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, L.; Kang, L.; Sun, K.; Jin, L.; Wang, H. Dynamics of Gut Microbiota in Japanese Tits (Parus minor) Across Developmental Stages: Composition, Diversity, and Associations with Body Condition. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 2840. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122840

Zhang L, Kang L, Sun K, Jin L, Wang H. Dynamics of Gut Microbiota in Japanese Tits (Parus minor) Across Developmental Stages: Composition, Diversity, and Associations with Body Condition. Microorganisms. 2025; 13(12):2840. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122840

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Li, Lele Kang, Keping Sun, Longru Jin, and Haitao Wang. 2025. "Dynamics of Gut Microbiota in Japanese Tits (Parus minor) Across Developmental Stages: Composition, Diversity, and Associations with Body Condition" Microorganisms 13, no. 12: 2840. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122840

APA StyleZhang, L., Kang, L., Sun, K., Jin, L., & Wang, H. (2025). Dynamics of Gut Microbiota in Japanese Tits (Parus minor) Across Developmental Stages: Composition, Diversity, and Associations with Body Condition. Microorganisms, 13(12), 2840. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122840