Propolis Exerts Antibiofilm Activity Against Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus by Modulating Gene Expression to Suppress Adhesion

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Propolis Substances and Bacterial Strains

2.2. Preparation of Propolis Ethanol Extract

2.3. UPLC-MS/MS Analysis

2.4. Determination of the Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC)

2.5. Determination of the Minimum Bactericidal Concentration (MBC)

2.6. Anti-Biofilm Assay

2.6.1. Inhibitory Effect of PEE on MRSA Biofilm Formation

2.6.2. Inhibitory Effect of PEE on Mature MRSA Biofilm

2.6.3. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) of Biofilm

2.6.4. Determination of Bacterial Adhesion

2.6.5. Analysis of Extracellular Polysaccharide Production

2.6.6. Analysis of Extracellular Proteins Synthesis

2.6.7. Real-Time Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-qPCR) Analysis of Gene Expression

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. PPE Chemical Composition

3.2. Antibacterial Activity

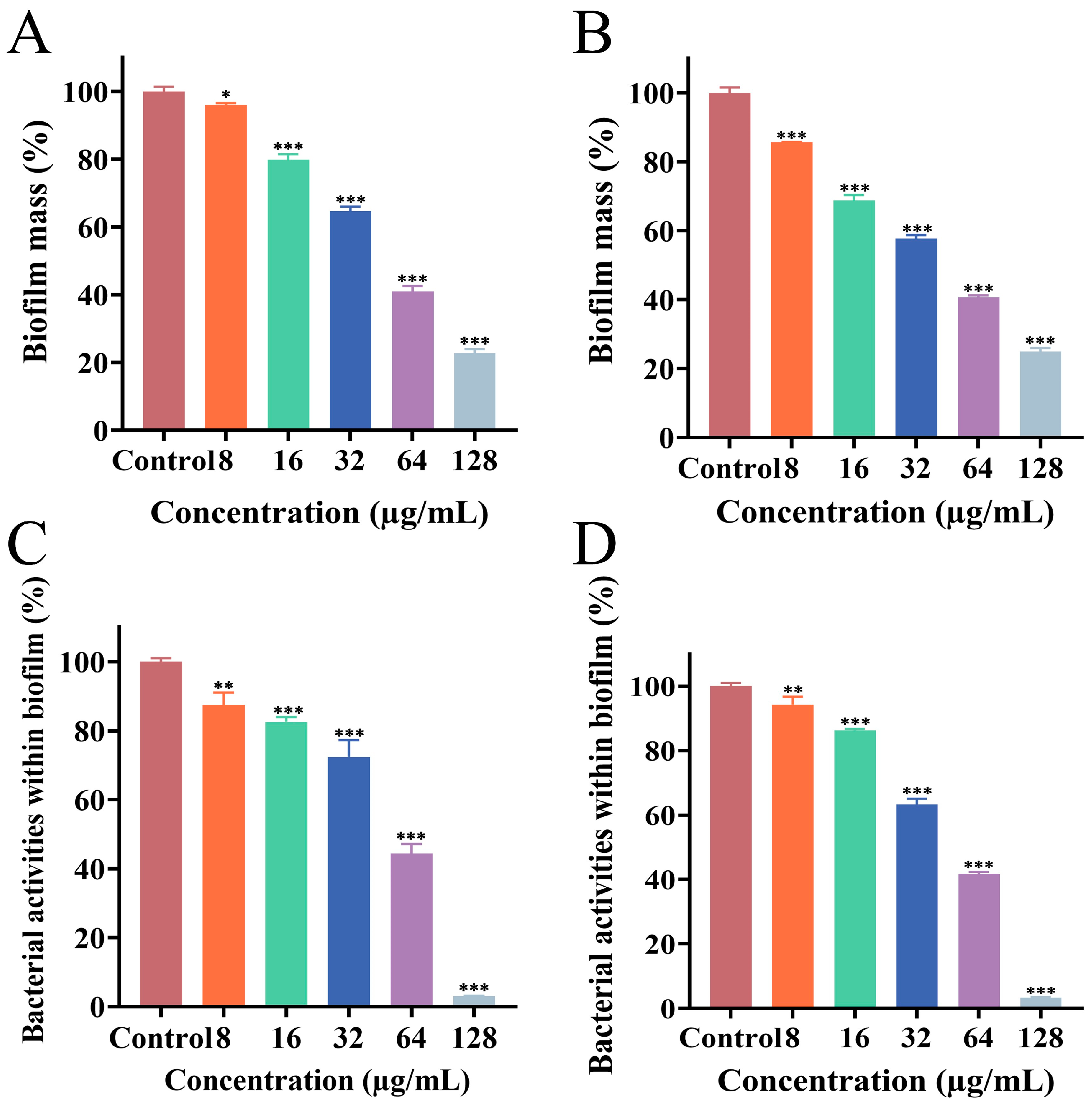

3.3. Effect of PEE on Biofilm Formation

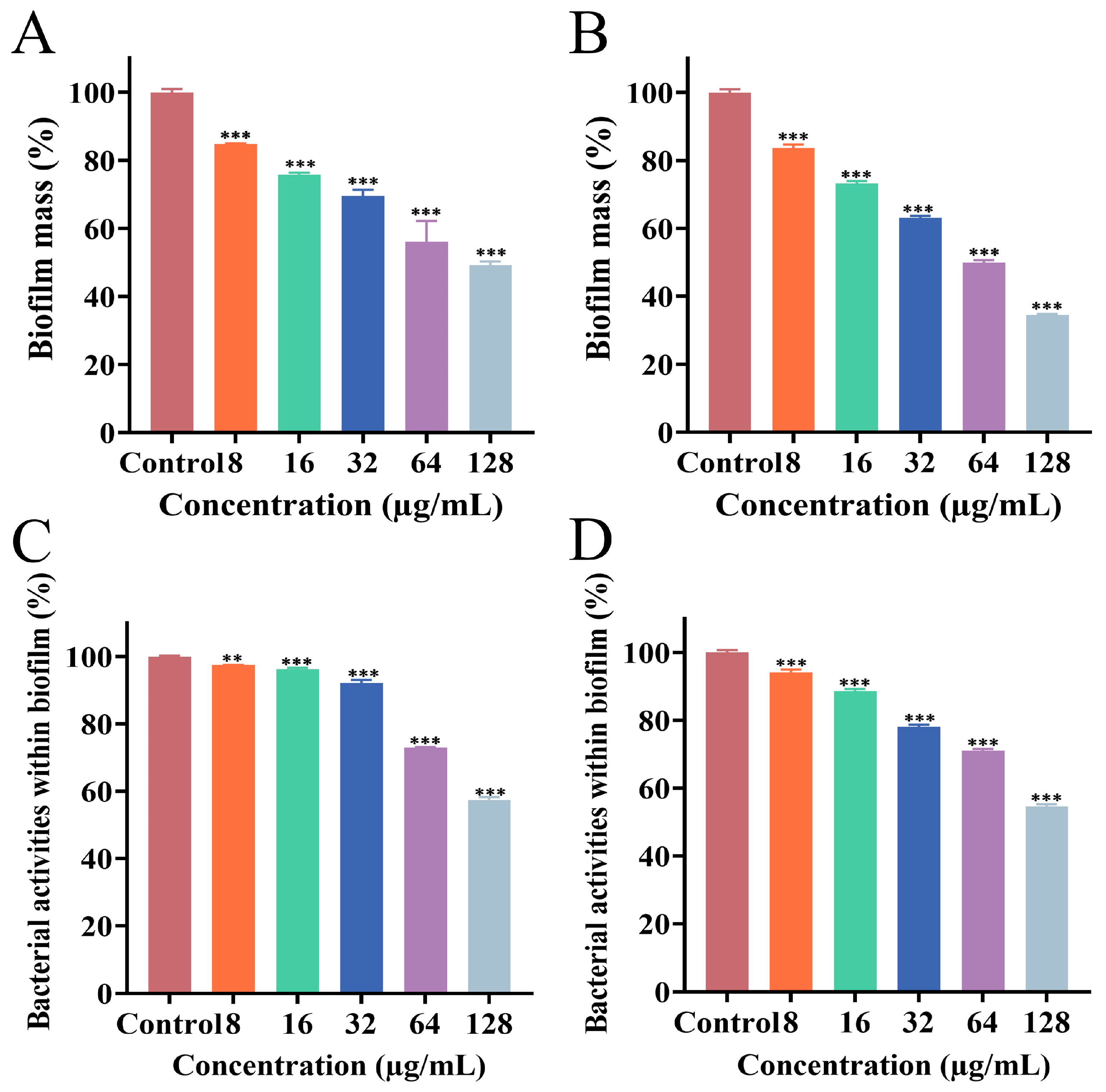

3.4. Effect of PEE on Mature Biofilm

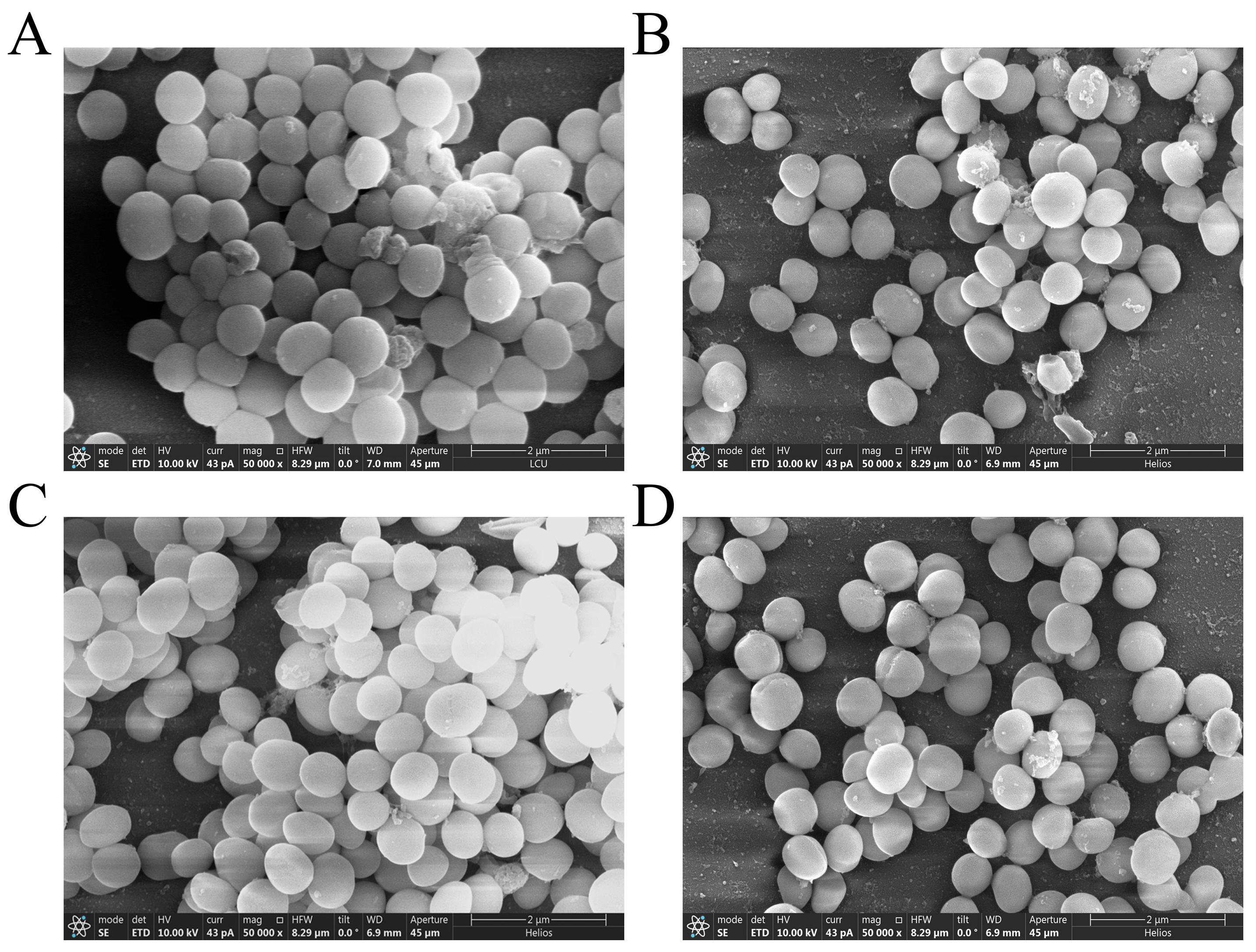

3.5. Effect of PEE on Biofilm Structure

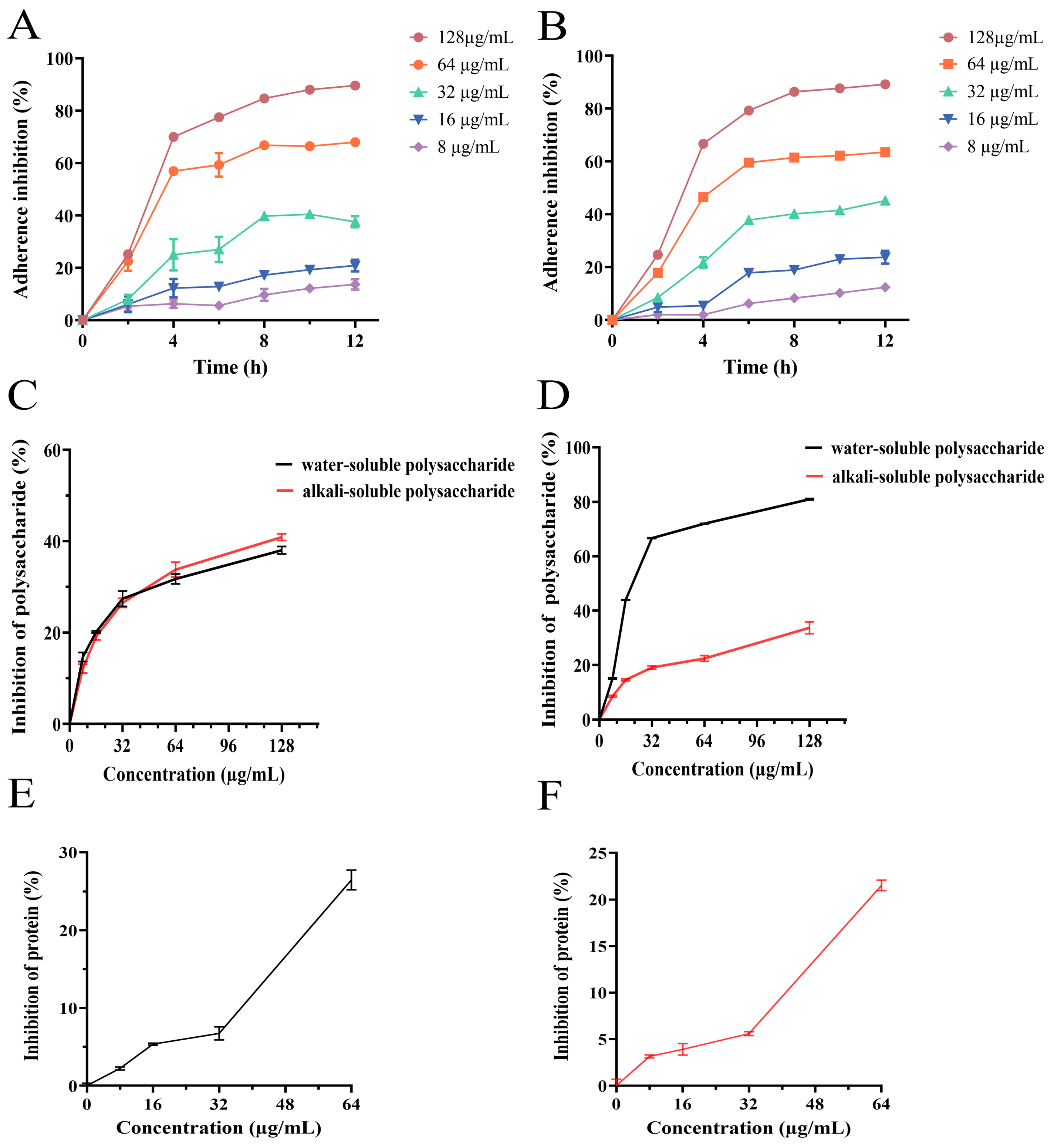

3.6. Effect of PEE on Bacterial Adhesion

3.7. Effect of PEE on Extracellular Polysaccharides Synthesis

3.8. Effect of PEE on Extracellular Proteins Synthesis

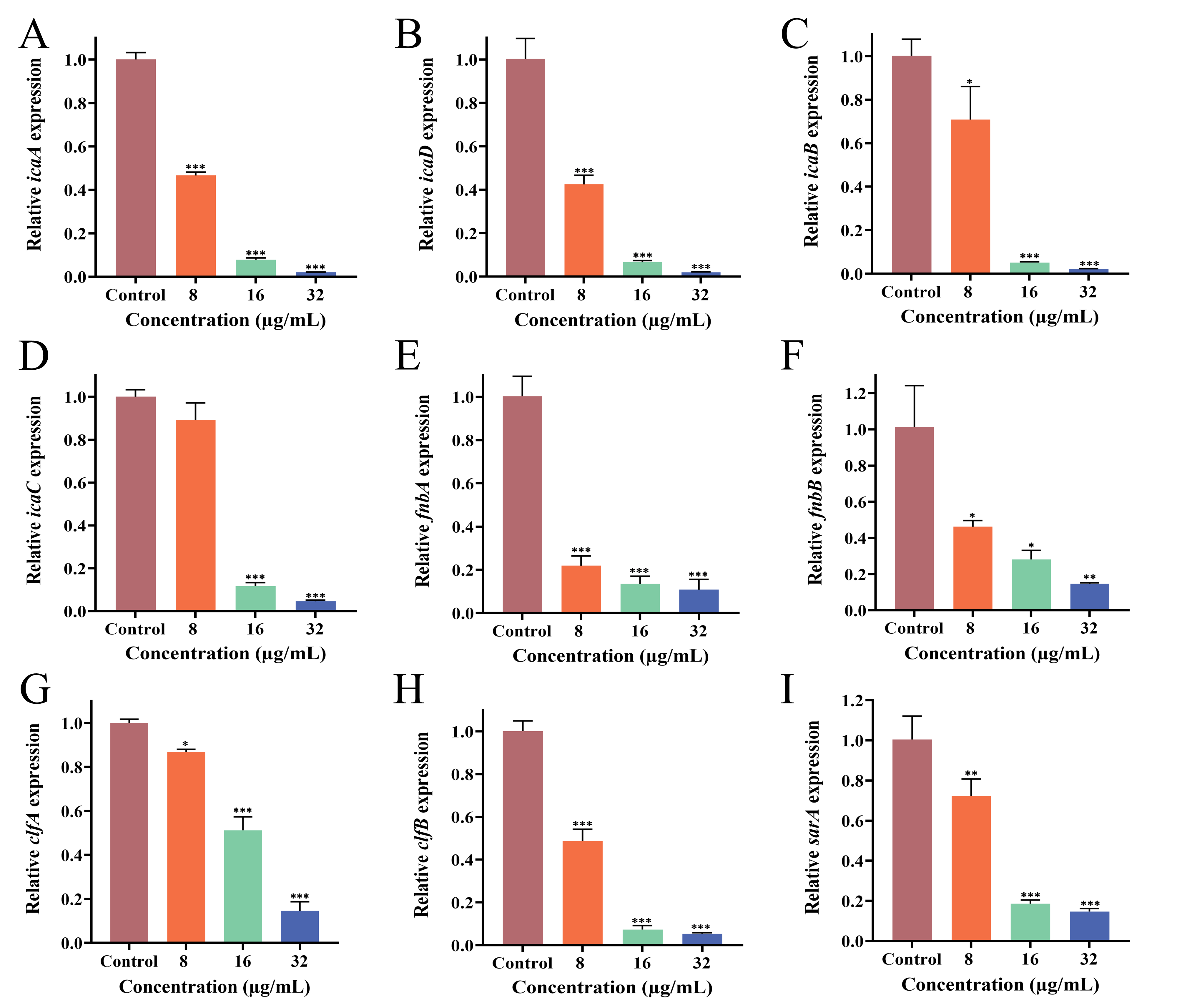

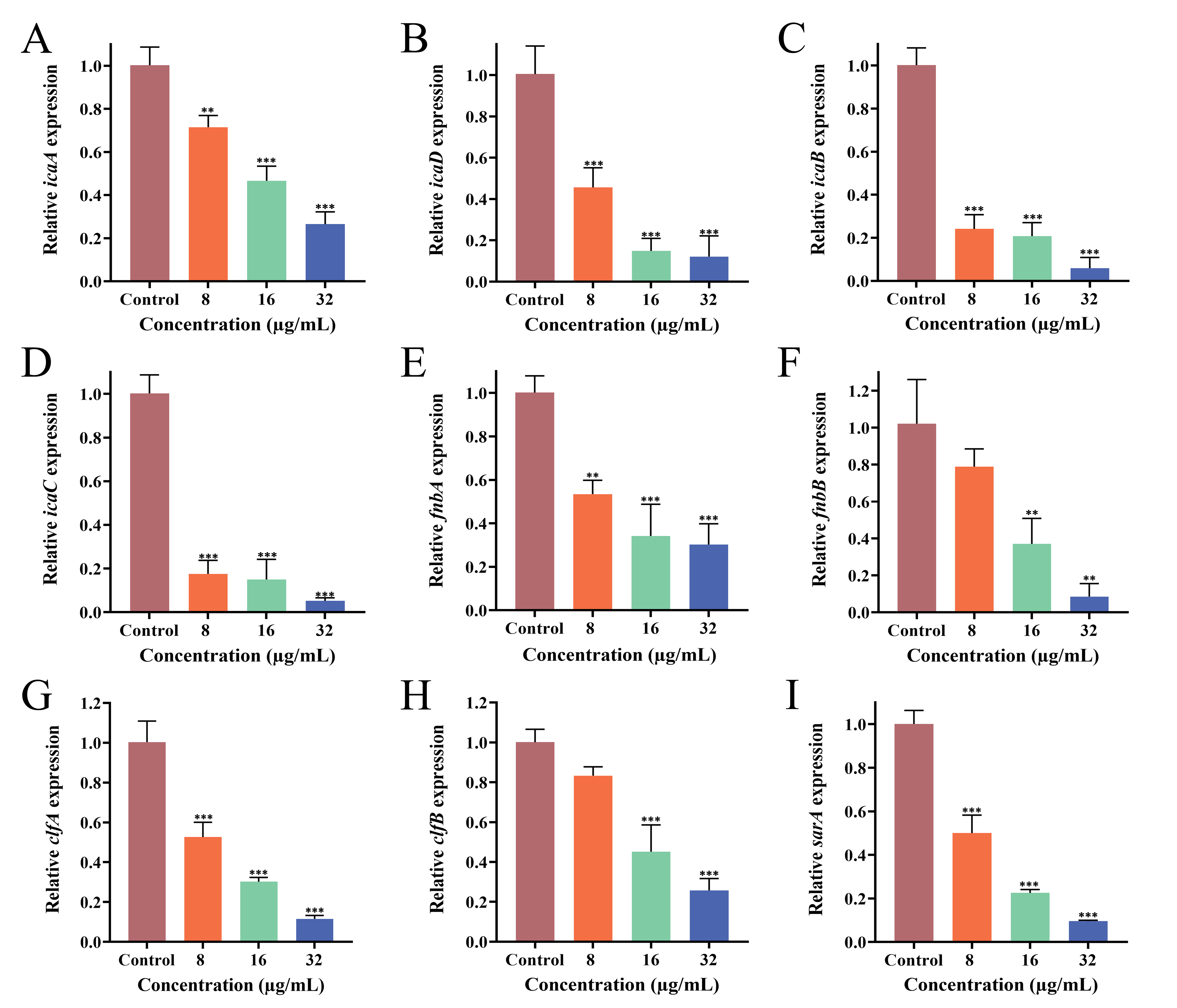

3.9. Effect of PEE on Biofilm-Related Gene Expression

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MRSA | Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus |

| PEE | Propolis Ethanolic Extract |

| MIC | Minimum Inhibitory Concentration |

| XTT | 2,3-Bis-(2-methoxy-4-nitro-5-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium-5-carboxanilide |

| CV | Crystal Violet |

| SEM | Scanning Electron Microscopy |

| PBP2a | Penicillin-Binding Proteins 2a |

| CFU | Colony-Forming Units |

| TSB | Trypticase soy broth |

| PBS | Phosphate-Buffered Saline |

| OD | Optical Density |

| RT-qPCR | Real-time quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| PIA | Polysaccharide Intercellular Adhesin |

References

- Peng, S.; Zhou, X.; Wang, Q.; Shen, L.; Wang, Z.Y.; Xu, H.; Yang, X.; Redshaw, C.; Zhang, Q.L. Cationic AIEgens with large rigid π-planes: Specific bacterial imaging and treatment of drug-resistant bacterial infections. Bioorganic Chem. 2025, 159, 108412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.C.; Wei, Y.P.; Chen, J.S.; Liu, X.; Mao, C.J.; Jin, B.K. A “signal-on” photoelectrochemical biosensor utilizing in-situ synthesis of SnS2/MgIn2S4 heterostructures and enzyme-assisted target cycling amplification for the sensitive detection of the mecA gene. Talanta 2025, 293, 128053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumana, B.; Manfred, B.; Shen, J.; Mur, L.A.J. Identification and metabolomic characterization of potent anti-MRSA phloroglucinol derivatives from Dryopteris crassirhizoma Nakai (Polypodiaceae). Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 961087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, A.P.; Nagvekar, V.C.; Veeraraghavan, B.; Warrier, A.R.; Ts, D.; Ahdal, J.; Jain, R. Current Perspectives on Treatment of Gram-Positive Infections in India: What Is the Way Forward? Interdiscip. Perspect. Infect. Dis. 2019, 2019, 7601847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Institute of Antibiotics; Huashan Hospital; Fudan University. China Bacterial Drug Resistance Monitoring Network [EB/OL]. 2023. Available online: https://www.carss.cn/ (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- Adalbert, J.R.; Karan, V.; Rache, T.; Rafael, P. Clinical outcomes in patients co-infected with COVID-19 and Staphylococcus aureus: A scoping review. BMC Infect. Dis. 2021, 21, 985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, M.A.; Sands, K.E.; Huang, S.S.; Kleinman, K.; Septimus, E.J.; Varma, N.; Blanchard, J.; Poland, R.E.; Coady, M.H.; Yokoe, D.S.; et al. Impact of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) on Healthcare-Associated Infections. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2022, 74, 1748–1754. [Google Scholar]

- Nandhini, P.; Kumar, P.; Mickymaray, S.; Alothaim, A.S.; Somasundaram, J.; Rajan, M. Recent Developments in Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) Treatment: A Review. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cascioferro, S.; Carbone, D.; Parrino, B.; Pecoraro, C.; Giovannetti, E.; Cirrincione, G.; Diana, P. Therapeutic strategies to counteract antibiotic resistance in MRSA biofilm-associated infections. ChemMedChem 2020, 16, 65–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Pan, J.; Wu, Y.; Xi, X.; Ma, C.; Wang, L.; Zhou, M.; Chen, T. PSN-PC: A Novel Antimicrobial and Anti-Biofilm Peptide from the Skin Secretion of Phyllomedusa-camba with Cytotoxicity on Human Lung Cancer Cell. Molecules 2017, 22, 1896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amador, C.I.; Røder, H.L.; Herschend, J.; Neu, T.R.; Burmølle, M. Decoding the impact of interspecies interactions on biofilm matrix components. Biofilm 2025, 9, 100271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arciola, C.R.; Campoccia, D.; Speziale, P.; Montanaro, L.; Costerton, J.W. Biofilm formation in Staphylococcus implant infections. A review of molecular mechanisms and implications for biofilm-resistant materials. Biomaterials 2012, 33, 5967–5982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamal, M.; Ahmad, W.; Andleeb, S.; Jalil, F.; Imran, M.; Nawaz, M.A.; Hussain, T.; Ali, M.; Rafiq, M.; Kamil, M.A. Bacterial biofilm and associated infections. J. Chin. Med. Assoc. 2018, 81, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen Kiong, N.; Cindy Shuan, J.T.; Nuryana, I.; Kwai, L.T.; Soo, T.N.; Sasheela, S.L.S.P. Investigation of biofilm formation in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus associated with bacteraemia in a tertiary hospital. Folia. Microbiol. 2021, 66, 741–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anmol, S.; Nidhi, V.; Vivek, K.; Pragati, A.; Vishnu, A. Biofilm inhibition/eradication: Exploring strategies and confronting challenges in combatting biofilm. Arch. Microbiol. 2024, 206, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elafify, M.; Liao, X.; Feng, J.; Ahn, J.; Ding, T. Biofilm formation in food industries: Challenges and control strategies for food safety. Food. Res. Int. 2024, 190, 114650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeedi, N.H.; Alanazi, A.D.; Alenazy, R.; Shater, A.F. Antimicrobial, Anti-inflammatory, Angiogenesis, and Wound Healing Activities of Copper Nanoparticles Green Synthesized by Lupinus arcticus Extract. IJ Pharm. Res. 2025, 24, e147434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarengaowa; Hu, W.; Feng, K.; Xiu, Z.; Jiang, A.; Lao, Y.; Li, Y.; Long, Y.; Guan, Y.; Ji, Y.; et al. Antimicrobial Mechanisms of Essential Oils and Their Components on Pathogenic Bacteria: A Review. Shipin Kexue/Food Sci. 2020, 41, 285–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almuhayawi, M.S. Propolis as a novel antibacterial agent. Saudi. J. Biol. Sci. 2020, 27, 3079–3086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przybyłek, I.; Karpiński, T.M. Antibacterial Properties of Propolis. Molecules 2019, 24, 2047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, N.; Marzieh, G.; Shima, A. Evaluation of Antibacterial Effect of Propolis and its Application in Mouthwash Production. Front. Dent. 2019, 16, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Guendouz, S.; Lyoussi, B.; Lourenço, J.P.; Rosa da Costa, A.M.; Miguel, M.G.; Barrocas Dias, C.; Manhita, A.; Jordao, L.; Nogueira, I.; Faleiro, M.L. Magnetite nanoparticles functionalized with propolis against methicillin resistant strains of Staphylococcus aureus. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2019, 102, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenwen, Z.; Escalada, M.G.; Di, W.; Wenqin, Y.; Sha, Y.; Suzhen, Q.; Xiaofeng, X.; Kai, W.; Liming, W. Antibacterial Activity of Chinese Red Propolis against Staphylococcus aureus and MRSA. Molecules 2022, 27, 1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobia, M.; Fizza, N.; Syed, R.; Khalid, A.; Shabnam, K.; Nawazish, A.S.; Hani, A.S. Analysis of the Antimicrobial and Anti-Biofilm Activity of Natural Compounds and Their Analogues against Staphylococcus aureus Isolates. Molecules 2022, 27, 6874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.Q.; Sharma-Kuinkel, B.K.; Casillas-Ituarte, N.N.; Fowler, V.G.; Rude, T.; DiBartola, A.C.; Lins, R.D.; Abdel-Hady, W.; Lower, S.K.; Bayer, A.S. Endovascular infections caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus are linked to clonal complex-specific alterations in binding and invasion domains of fibronectin-binding protein A as well as the occurrence of fnbB. Infect. Immun. 2015, 83, 4772–4780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otsuka, T.; Saito, K.; Dohmae, S.; Takano, T.; Higuchi, W.; Takizawa, Y.; Okubo, T.; Iwakura, N.; Yamamoto, T. Key adhesin gene in community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2006, 346, 1234–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Li, J.; Jia, J.; Yang, Y.; Wu, X.; Hong, X.; Chen, Z.; Xiao, Y. Promoter Engineering and Two-Phase Whole-Cell Catalysis Improve the Biosynthesis of Naringenin in E. coli. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2025, 73, 11157–11167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, J.; Thombre, K.; Gupta, K.; Umekar, M. Apigenin Bioisosteres: Synthesis and Evaluation of their Antioxidant, Antimicrobial, and Anticancer Activities. Lett. Org. Chem. 2024, 21, 1023–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adesina, A.F.; Adewuyi, A.; Otuechere, C.A. Exploratory studies on chrysin via antioxidant, antimicrobial, ADMET, PASS and molecular docking evaluations. Pharmacol. Res.-Mod. Chin. Med. 2024, 11, 100413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, R.; Lin, L.; Liu, Y.; Li, H. Bibliometric and visual analysis of global publications on kaempferol. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1442574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qatouseh, L.F.A.; Ahmad, M.I.; Amorim, C.G.; Adham, I.S.I.A.; Collier, P.J.; Montenegro, M.C.B.S.M. Insights into the molecular antimicrobial properties of ferulic acid against Helicobacter pylori. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2025, 136, lxaf112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sang, H.; Jin, H.; Song, P.; Xu, W.; Wang, F. Gallic acid exerts antibiofilm activity by inhibiting methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus adhesion. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 17220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokilakanit, P.; Dungkhuntod, N.; Serikul, N.; Koontongkaew, S.; Utispan, K. Caffeic acid phenethyl ester inhibits multispecies biofilm formation and cariogenicity. PeerJ 2025, 13, e18942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felix, Z.; Kavita, C.; Kowacz, M.; Ravalia, M.; Kripal, K.; Fearnley, J.; Perera, C.O. Antiviral, Antibacterial, Antifungal, and Antiparasitic Properties of Propolis: A Review. Foods 2021, 10, 1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lister, J.L.; Horswill, A.R. Staphylococcus aureus biofilms: Recent developments in biofilm dispersal. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2014, 4, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Till, A.; Stefan, R.; Ralf, R.; Kay, N.; Friedrich, G. Phylogeny of the staphylococcal major autolysin and its use in genus and species typing. J. Bacteriol. 2012, 194, 2630–2636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tilahun, A.Y.; Karau, M.; Ballard, A.; Gunaratna, M.P.; Thapa, A.; David, C.S.; Patel, R.; Rajagopalan, G. The impact of Staphylococcus aureus-associated molecular patterns on staphylococcal superantigen-induced toxic shock syndrome and pneumonia. Mediat. Inflamm. 2014, 2014, 468285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayad, A.S.; Benchaabane, S.; Daas, T.; Smagghe, G.; Ayad, W.L. Propolis Stands out as a Multifaceted Natural Product: Meta-Analysis on Its Sources, Bioactivities, Applications, and Future Perspectives. Life 2025, 15, 764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Yuan, W.Q.; Guo, Y.Y.; Wu, Q.; Wang, F.; Xuan, H.Z. Anti-Biofilm Activities of Chinese Poplar Propolis Essential Oil against Streptococcus mutans. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, W.M.; Zhang, Z.; Shuai, X.X.; Zhou, X.D.; Yin, D.R. Caffeic Acid Phenethyl Ester (CAPE) Inhibits Cross-Kingdom Biofilm Formation of Streptococcus mutans and Candida albicans. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022, 10, e0157822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, A.; Malik, A.; Sobti, R.C. Anti-bacterial Properties of Propolis: A Comprehensive Review. Curr. Microbiol. 2025, 82, 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Silva, W.H.T.; Guedes, F.R.; Candeiro, C.L.L.; dos Santos, C.M.M.L.; Ambrosio, M.A.L.V.; Veneziani, R.C.S.; Bastos, J.K.; Santiago, M.B.; Martins, C.H.G.; Turrioni, A.P. Effect of Brazilian green and brown propolis on human pulp cells and bacteria involved in primary endodontic infection: Ex Vivo study. Arch. Oral Biol. 2025, 176, 106294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Yuan, J.; Li, J.; Liu, H.; Wei, F.; Xuan, H. Antibacterial activity of Chinese propolis and its synergy with β-lactams against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2022, 53, 1789–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manginstar, C.O.; Tallei, T.E.; Salaki, C.L.; Niode, N.J.; Jaya, H.K. Dual anti-inflammatory and antimicrobial effects of stingless bee propolis on second-degree burns. Narra J. 2025, 5, e2359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glevitzky, M.; Corcheş, M.T.; Popa, M.; Glevitzky, I.; Vică, M.L. Propolis: Biological Activity and Its Role as a Natural Indicator of Pollution in Mining Areas. Environments 2025, 12, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, K.; Sang, H.; Jin, H.; Song, P.; Xu, W.; Xuan, H.; Wang, F. Antimicrobial Activities of Propolis Nanoparticles in Combination with Ampicillin Sodium Against Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, W.; Yan, J. Mechanical stabilization of a bacterial adhesion complex. Biophys. J. 2023, 122, 267a. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katrin, S.; Alexander, R.H. Staphylococcal Biofilm Development: Structure, Regulation, and Treatment Strategies. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. MMBR 2020, 84, e00026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni-Eidhin, D.; Perkins, S.; Francois, P.; Vaudaux, P.; Hook, M.; Foster, T.J. Clumping factor B (ClfB), a new surface-located fibrinogen-binding adhesin of Staphylococcus. Mol. Microbiol. 1998, 30, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, Y.; Xu, Y.; Liang, X.W.; Keene, D.R.; Höök, A.; Gurusiddappa, S.; Höök, M.; Narayana, S.V. A ‘Collagen Hug’ model for Staphylococcus aureus CNA binding to collagen. EMBO J. 2005, 24, 4224–4236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kot, B.; Sytykiewicz, H.; Sprawka, I.; Witeska, M. Effect of manuka honey on biofilm-associated genes expression during methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus biofilm formation. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 13552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, N.; Tan, X.; Jiao, Y.; Liu, L.; Zhao, W.; Yang, S.; Jia, A. RNA-Seq-based transcriptome analysis of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus biofilm inhibition by ursolic acid and resveratrol. Sci. Rep. 2014, 1, 5467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soltani, E.; Farrokhi, E.; Zamanzad, B.; Abadi, M.S.S.; Deris, F.; Soltani, A.; Gholipour, A. Prevalence and distribution of adhesins and the expression of fibronectin-binding protein (FnbA and FnbB) among Staphylococcus aureus isolates from Shahrekord Hospitals. BMC Res. Notes 2019, 12, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tola, J.D.; Orellana, P.; Andrade, C.F.; Torracchi, J.E.; Delgado, D.A.; Pavón, A.; Carchi, D.G. Molecular analysis of the ica adhesion gene in Staphylococcus aureus strains, isolated from inert surfaces in clinical and hospital areas. Genet. Mol. Res. 2024, 23, gmr2344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gene | Primer Sequence (5′→3′) | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| icaA | F: CTTGCTGGCGCAGTCAATAC | [23] |

| R: GTAGCCAACGTCGACAACTG | ||

| icaD | F: TGGGCATTTTCGCGATTATCA | [23] |

| R: ACGATTCTCTTCCTTTCTGCCA | ||

| icaB | F: CCTGTAAGCACACTGGATGG | [23] |

| R: TCGCTTTTCTTACACGGTGA | ||

| icaC | F: TGCGTTAGCAAATGGAGACT | [23] |

| R: TGCGTGCAAATACCCAAGAT | ||

| fnbA | F: AAATTGGGAGCAGCATCAGT | [24] |

| R: GCAGCTGAATTCCCATTTTC | ||

| fnbB | F: CAACCAGTCGTTAAGCTCTGTGAC | [25] |

| R: GCTGACATCATCAAGCTTTGC | ||

| clfA | F: ACCCAGGTTCAGATTCTGGCAGCG | [24] |

| R: TCGCTGAGTCGGAATCGCTTGCT | ||

| clfB | F: ACATCAGTAATAGTAGGGGGCAAC | [26] |

| R: TTCGCACTGTTTGTGTTTGCAC | ||

| sarA | F: GTAATGAGCATGATGAAAGAACTGT | [23] |

| R: CGTTGTTTGCTTCAGTGATTCG | ||

| 16S rRNA | F: CGCAATGGGCGAAAGC | [23] |

| R: TACGATCCGAAGACCTTCATCA |

| Compounds | Structural Formula | Molecular Formula | Retention Time (min) | Content (mg/g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| caffeic acid |  | C9H8O4 | 3.47 | 3.93 ± 0.068 |

| ferulic acid |  | C10H10O4 | 5.13 | 0.78 ± 0.001 |

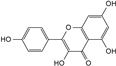

| Quercetin |  | C15H10O7 | 5.72 | 1.01 ± 0.027 |

| Apigenin |  | C15H10O5 | 5.94 | 0.73 ± 0.006 |

| cinnamic acid |  | C9H8O2 | 5.96 | 0.11 ± 0.005 |

| kaempferol |  | C15H10O6 | 5.98 | 0.66 ± 0.007 |

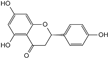

| Naringenin |  | C15H12O5 | 6.05 | 1.41 ± 0.029 |

| Chrysin |  | C15H10O4 | 6.55 | 12.38 ± 0.426 |

| Galangin |  | C15H10O5 | 6.61 | 8.37 ± 0.042 |

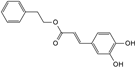

| phenethyl caffeate |  | C17H16O4 | 6.65 | 8.84 ± 0.150 |

| Compound | Strain | MIC (µg/mL) | MBC (µg/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|

| PEE | MRSA ATCC 43300 | 128 | 256 |

| MRSA CI2 | 128 | 256 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sang, H.; Feng, K.; Ju, Y.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Xuan, H.; Wang, F. Propolis Exerts Antibiofilm Activity Against Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus by Modulating Gene Expression to Suppress Adhesion. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 2810. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122810

Sang H, Feng K, Ju Y, Sun Y, Zhang Y, Xuan H, Wang F. Propolis Exerts Antibiofilm Activity Against Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus by Modulating Gene Expression to Suppress Adhesion. Microorganisms. 2025; 13(12):2810. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122810

Chicago/Turabian StyleSang, He, Kaiyue Feng, Yanhu Ju, Yueying Sun, Yang Zhang, Hongzhuan Xuan, and Fei Wang. 2025. "Propolis Exerts Antibiofilm Activity Against Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus by Modulating Gene Expression to Suppress Adhesion" Microorganisms 13, no. 12: 2810. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122810

APA StyleSang, H., Feng, K., Ju, Y., Sun, Y., Zhang, Y., Xuan, H., & Wang, F. (2025). Propolis Exerts Antibiofilm Activity Against Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus by Modulating Gene Expression to Suppress Adhesion. Microorganisms, 13(12), 2810. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122810