From Surfaces to Spillover: Environmental Persistence and Indirect Transmission of Influenza A(H3N8) Virus

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Viruses

2.2. Genome Sequencing and Phylogenetic Analysis

2.3. Receptor-Binding Specificity Identification

2.4. Growth Dynamics in Cells

2.5. Mouse Experiments

2.6. Assessment of Viral Environmental Persistence

2.7. Transmission Experiments Among Guinea Pigs

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

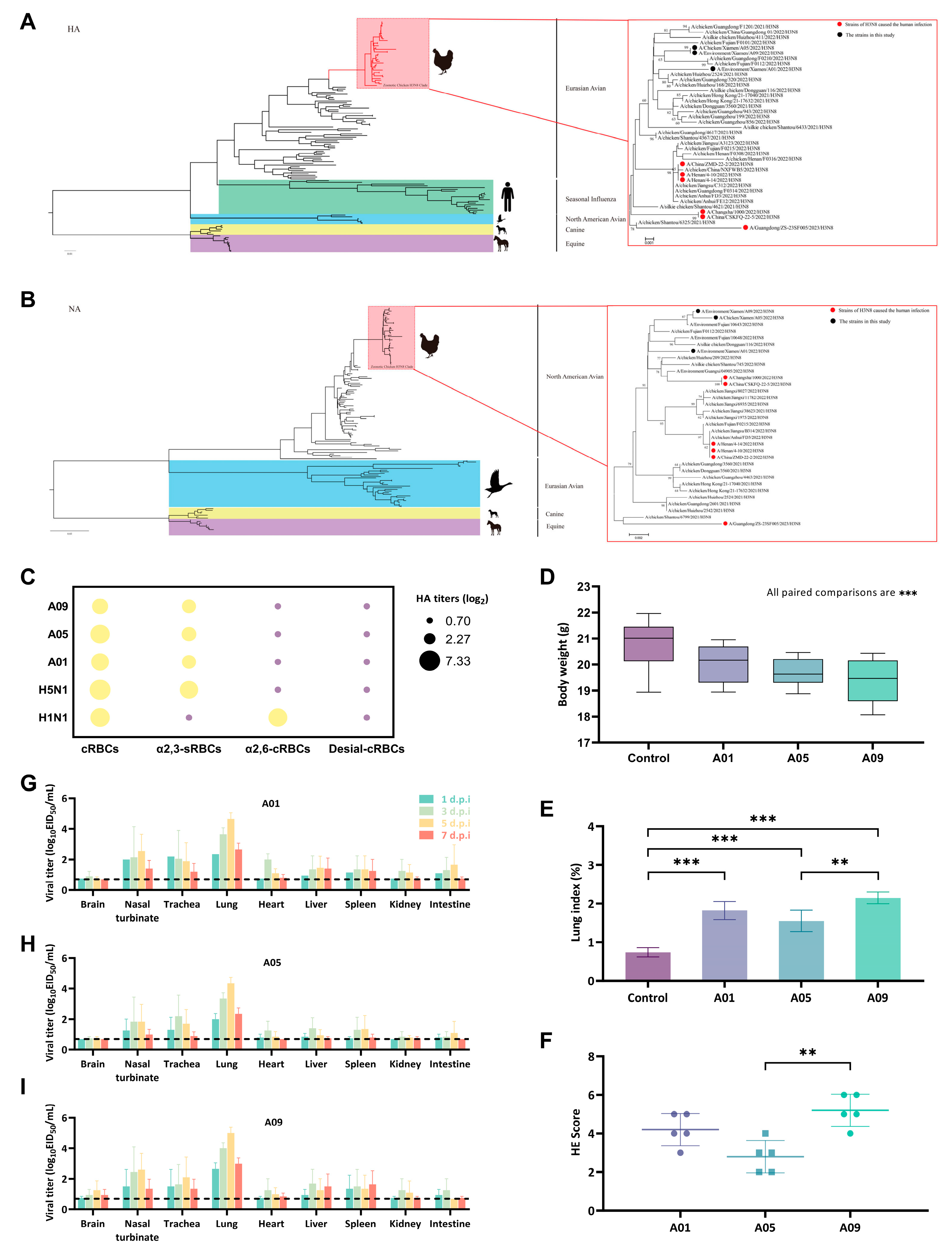

3.1. Genotype-to-Phenotype Insights into H3N8 Adaptation of Cross-Species Infection

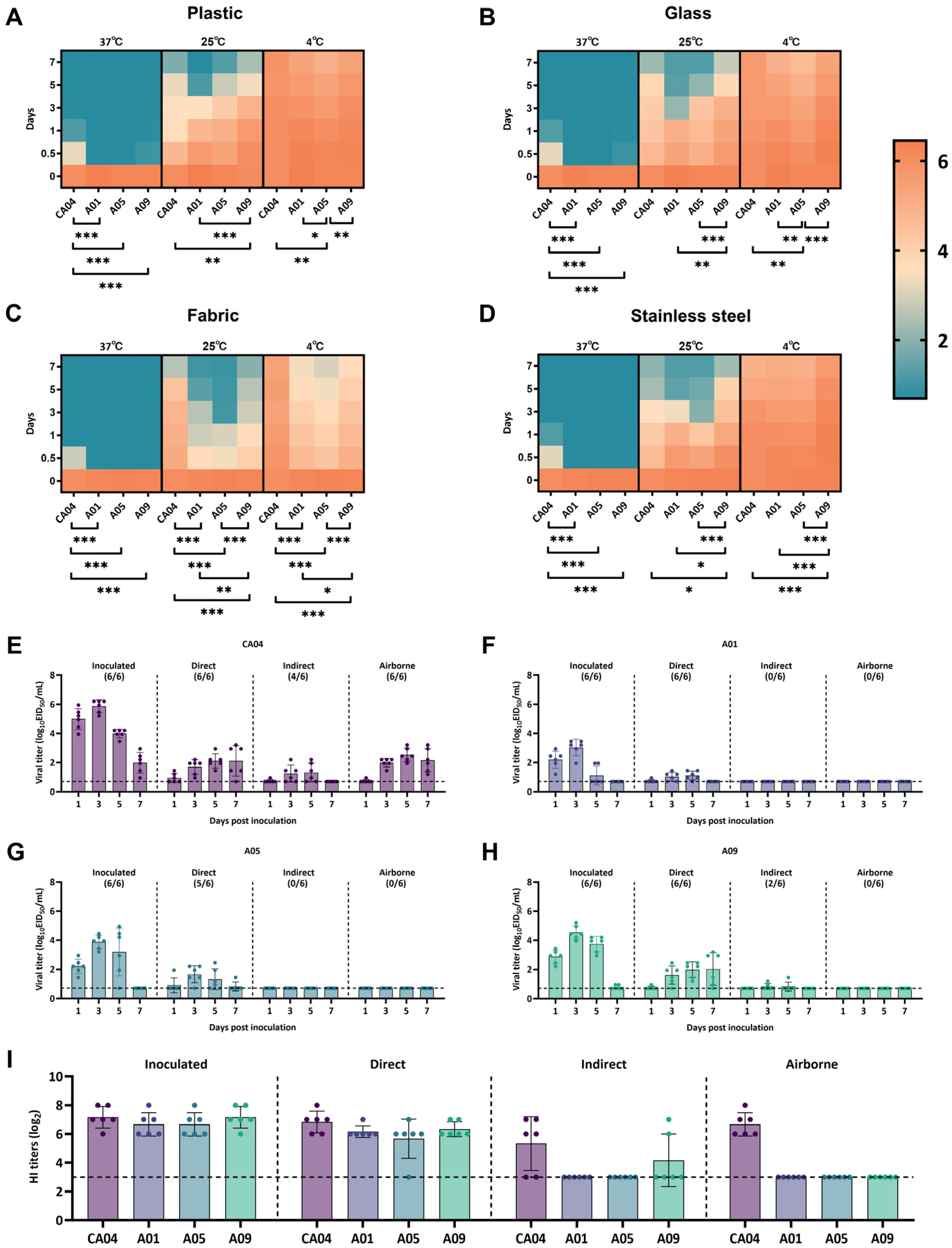

3.2. Environmental Persistence of H3N8 Under Diverse Temperature and Surface Conditions

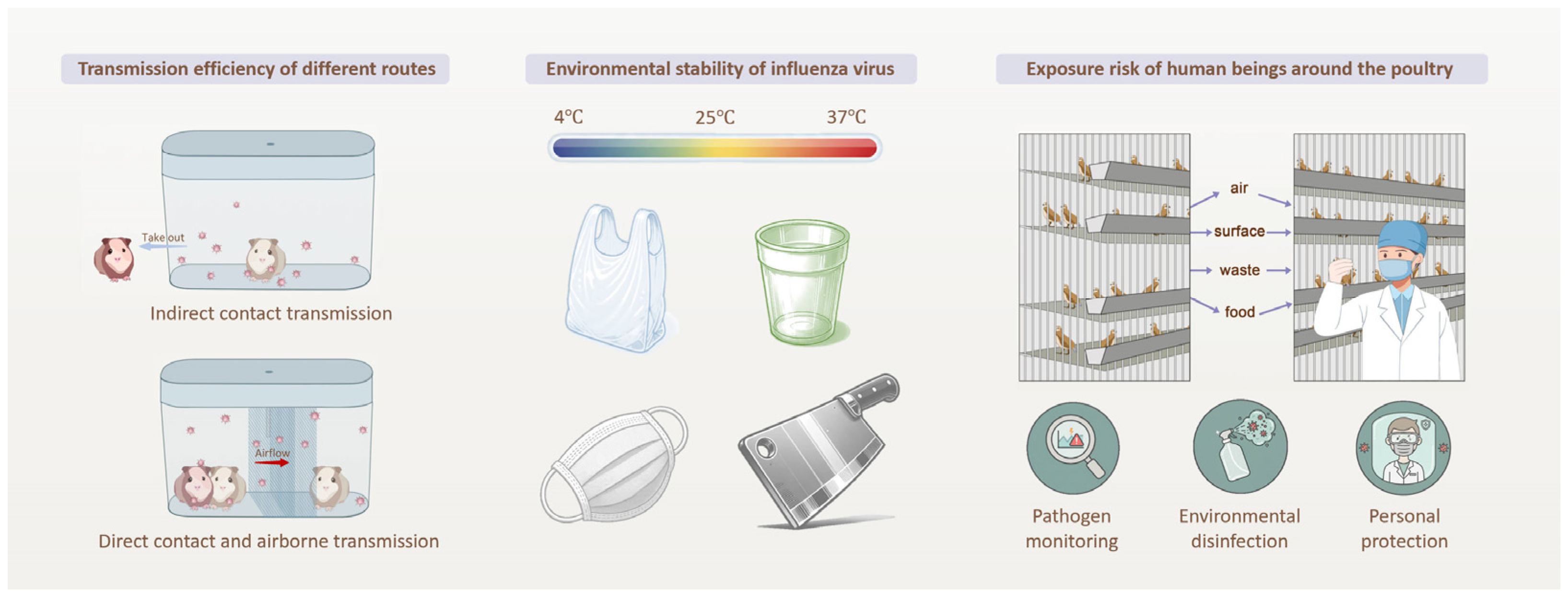

3.3. Multi-Route Transmission Drive H3N8 Infection Risk

4. Conclusion and Discussion

4.1. Summary of This Study

4.2. Environmental Biohazard Monitoring

4.3. Environmental Biohazard Disinfection

4.4. Further Outlook: A Risk-to-Response Framework

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AIV | Avian influenza virus |

| LPMs | Live poultry markets |

| ML | Maximum likelihood |

| MCMC | Markov chain Monte Carlo |

| MCC | maximum clade credibility |

| cRBCs | chicken red blood cells |

| VCNA | Vibrio cholerae neuraminidase |

| MOI | multiple of infection |

| EID50 | Median infective dose |

| HI | Hemagglutination inhibition |

| digital PCR | digital polymerase chain reaction |

| RT-qPCR | reverse-transcription quantitative PCR |

| CRISPR-NGS | CRISPR-Cas9-enriched next-generation sequencing |

| QMRA | quantitative microbial risk assessment |

| AI | artificial intelligence |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

References

- Jin, Y.; Cui, H.; Jiang, L.; Zhang, C.; Li, J.; Cheng, H.; Chen, Z.; Zheng, J.; Zhang, Y.; Fu, Y.; et al. Evidence for human infection with avian influenza A(H9N2) virus via environmental transmission inside live poultry market in Xiamen, China. J. Med. Virol. 2023, 95, e28242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, P.; Niu, M.; Li, Y.; Xu, M.; Zhao, T.; Cao, X.; Liang, C.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Xiao, C. Human infection with H3N8 avian influenza virus: A novel H9N2-original reassortment virus. J. Infect. 2022, 85, e187–e189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Li, M.; Li, Y.; Bai, X.; Song, X.; Zhao, Z.; Ge, S.; Li, Y.; Liu, J.; Shi, J.; et al. H3N8 subtype avian influenza virus originated from wild birds exhibited dual receptor-binding profiles. J. Infect. 2023, 86, e36–e39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Sun, H.; Gao, F.; Luo, K.; Huang, Z.; Tong, Q.; Song, H.; Han, Q.; Liu, J.; Lan, Y.; et al. Human infection of avian influenza A H3N8 virus and the viral origins: A descriptive study. Lancet Microbe 2022, 3, e824–e834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, M.; Wang, L.F.; Sun, B.W.; Wan, W.B.; Ji, X.; Baele, G.; Bi, Y.H.; Suchard, M.A.; Lai, A.; Zhang, M.; et al. Zoonotic infections by avian influenza virus: Changing global epidemiology, investigation, and control. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2024, 24, e522–e531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, J.; Ruan, J.; Lin, Q.; Ren, T.; Chen, L. China faces the challenge of influenza A virus, including H3N8, in the post-COVID-19 era. J. Infect. 2023, 87, e39–e41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.J.; Liu, P.; Lei, W.; Jia, Z.; He, X.; Shi, W.; Tan, Y.; Zou, S.; Wong, G.; Wang, J.; et al. Surveillance of SARS-CoV-2 at the Huanan Seafood Market. Nature 2024, 631, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Gong, Y.; Zhang, C.; Sun, J.; Wong, G.; Shi, W.; Liu, W.; Gao, G.F.; Bi, Y. Co-existence and co-infection of influenza A viruses and coronaviruses: Public health challenges. Innovation 2022, 3, 100306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Altan-Bonnet, N.; Shen, Y.; Shuai, D. Waterborne Human Pathogenic Viruses in Complex Microbial Communities: Environmental Implication on Virus Infectivity, Persistence, and Disinfection. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 5381–5389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyazaki, H.; Hirose, R.; Ichikawa, M.; Mukai, H.; Yamauchi, K.; Nakaya, T.; Itoh, Y. Methods for virus recovery from environmental surfaces to monitor infectious viral contamination. Environ. Int. 2023, 180, 108199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amarasiri, M.; Kitajima, M.; Nguyen, T.H.; Okabe, S.; Sano, D. Bacteriophage removal efficiency as a validation and operational monitoring tool for virus reduction in wastewater reclamation: Review. Water Res. 2017, 121, 258–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, A.; Amin, E.; Munro, S.; Hossain, M.E.; Islam, S.; Hassan, M.M.; Al Mamun, A.; Samad, M.A.; Shirin, T.; Rahman, M.Z.; et al. Potential risk zones and climatic factors influencing the occurrence and persistence of avian influenza viruses in the environment of live bird markets in Bangladesh. One Health 2023, 17, 100644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Zhou, J.; Cheng, K.; Wu, J.; Zhong, Z.; Song, Y.; Ke, C.; Yen, H.L.; Li, Y. Assessing the risk of downwind spread of avian influenza virus via airborne particles from an urban wholesale poultry market. Build. Environ. 2018, 127, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morin, C.W.; Stoner-Duncan, B.; Winker, K.; Scotch, M.; Hess, J.J.; Meschke, J.S.; Ebi, K.L.; Rabinowitz, P.M. Avian influenza virus ecology and evolution through a climatic lens. Environ. Int. 2018, 119, 241–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, C.; Zhou, A.; O’Brien, K.; Jamal, Y.; Wennerdahl, H.; Schmidt, A.R.; Shisler, J.L.; Jutla, A.; Schmidt, A.R.; Keefer, L.; et al. Application of neighborhood-scale wastewater-based epidemiology in low COVID-19 incidence situations. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 852, 158448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood, J.P.; Choi, Y.W.; Chappie, D.J.; Rogers, J.V.; Kaye, J.Z. Environmental persistence of a highly pathogenic avian influenza (H5N1) virus. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010, 44, 7515–7520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, K.A.; Bennett, A.M. Persistence of influenza on surfaces. J. Hosp. Infect. 2017, 95, 194–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perlas, A.; Bertran, K.; Abad, F.X.; Borrego, C.M.; Nofrarías, M.; Valle, R.; Pailler-García, L.; Ramis, A.; Cortey, M.; Acuña, V.; et al. Persistence of low pathogenic avian influenza virus in artificial streams mimicking natural conditions of waterfowl habitats in the Mediterranean climate. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 863, 160902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Li, Y.; Chen, J.; Chen, Q.; Chen, Z. Perpetuation of H5N1 and H9N2 avian influenza viruses in natural water bodies. J. Gen. Virol. 2014, 95, 1430–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oxford, J.; Berezin, E.N.; Courvalin, P.; Dwyer, D.E.; Exner, M.; Jana, L.A.; Kaku, M.; Lee, C.; Letlape, K.; Low, D.E.; et al. The survival of influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 virus on 4 household surfaces. Am. J. Infect. Control 2014, 42, 423–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulliette, A.D.; Perry, K.A.; Edwards, J.R.; Noble-Wang, J.A. Persistence of the 2009 Pandemic Influenza A (H1N1) Virus on N95 Respirators. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2013, 79, 2148–2155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Zheng, S.; Sun, J.; Wu, H.; Zhang, D.; Wang, Y.; Tian, T.; Zhu, L.; Wu, Z.; Li, L.; et al. A human-infecting H10N5 avian influenza virus: Clinical features, virus reassortment, receptor-binding affinity, and possible transmission routes. J. Infect. 2025, 90, 106456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Zheng, T.; Jia, M.; Wang, Y.; Yang, J.; Liu, Y.; Yang, P.; Xie, Y.; Sun, H.; Tong, Q.; et al. Dual receptor-binding, infectivity, and transmissibility of an emerging H2N2 low pathogenicity avian influenza virus. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 10012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Li, J.; Sun, J.; Li, J.; Fu, G.; Tian, T.; Yang, Y.; Lu, X.; Li, S.; Wang, L.; et al. Genetic diversity of H9N2 avian influenza viruses in poultry across China and implications for zoonotic transmission. Nat. Microbiol. 2025, 10, 1378–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Li, H.; Tong, Q.; Han, Q.; Liu, J.; Yu, H.; Song, H.; Qi, J.; Li, J.; Yang, J.; et al. Airborne transmission of human-isolated avian H3N8 influenza virus between ferrets. Cell 2023, 186, 4074–4084.e4011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieuwenhuijsen, M.J. New urban models for more sustainable, liveable and healthier cities post covid19; reducing air pollution, noise and heat island effects and increasing green space and physical activity. Environ. Int. 2021, 157, 106850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wobus, C.E.; Nguyen, T.H. Viruses are everywhere—What do we do? Curr. Opin. Virol. 2012, 2, 60–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundy, L.; Fatta-Kassinos, D.; Slobodnik, J.; Karaolia, P.; Cirka, L.; Kreuzinger, N.; Castiglioni, S.; Bijlsma, L.; Dulio, V.; Deviller, G.; et al. Making Waves: Collaboration in the time of SARS-CoV-2—Rapid development of an international co-operation and wastewater surveillance database to support public health decision-making. Water Res. 2021, 199, 117167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Been, F.; Emke, E.; Matias, J.; Baz-Lomba, J.A.; Boogaerts, T.; Castiglioni, S.; Campos-Mañas, M.; Celma, A.; Covaci, A.; de Voogt, P.; et al. Changes in drug use in European cities during early COVID-19 lockdowns—A snapshot from wastewater analysis. Environ. Int. 2021, 153, 106540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villanueva Cristina, M.; Kogevinas, M.; Cordier, S.; Templeton Michael, R.; Vermeulen, R.; Nuckols John, R.; Nieuwenhuijsen Mark, J.; Levallois, P. Assessing Exposure and Health Consequences of Chemicals in Drinking Water: Current State of Knowledge and Research Needs. Environ. Health Perspect. 2014, 122, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, B.; Lal, H.; Srivastava, A. Review of bioaerosols in indoor environment with special reference to sampling, analysis and control mechanisms. Environ. Int. 2015, 85, 254–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, M.; Eiguren-Fernandez, A.; Hsieh, H.; Afshar-Mohajer, N.; Hering, S.V.; Lednicky, J.; Hugh Fan, Z.; Wu, C.Y. Efficient collection of viable virus aerosol through laminar-flow, water-based condensational particle growth. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2016, 120, 805–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Chen, J.; Nannu Shankar, S.; Amanatidis, S.; Eiguren-Fernandez, A.; Kreisberg, N.; Spielman, S.; Lednicky, J.A.; Wu, C.-Y. The BioCascade impactor: A novel device for direct collection of size-fractionated bioaerosols into liquid medium. Aerosol Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 264–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, K.K.; Tay, D.J.W.; Tan, K.S.; Ong, S.W.X.; Than, T.S.; Koh, M.H.; Chin, Y.Q.; Nasir, H.; Mak, T.M.; Chu, J.J.H.; et al. Viral Load of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) in Respiratory Aerosols Emitted by Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) While Breathing, Talking, and Singing. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2022, 74, 1722–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardi, M.; Belmouden, A.; Aghrouch, M.; Lotfy, A.; Idaghdour, Y.; Lemkhente, Z. Wastewater genomic surveillance to track infectious disease-causing pathogens in low-income countries: Advantages, limitations, and perspectives. Environ. Int. 2024, 192, 109029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sedlak Ruth, H.; Cook, L.; Cheng, A.; Magaret, A.; Jerome Keith, R. Clinical Utility of Droplet Digital PCR for Human Cytomegalovirus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2014, 52, 2844–2848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuevas-Ferrando, E.; Girón-Guzmán, I.; Falcó, I.; Pérez-Cataluña, A.; Díaz-Reolid, A.; Aznar, R.; Randazzo, W.; Sánchez, G. Discrimination of non-infectious SARS-CoV-2 particles from fomites by viability RT-qPCR. Environ. Res. 2022, 203, 111831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, L.; Jin, Y.; Li, J.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, Y.; Cheng, H.; Lu, B.; Zheng, J.; Li, L.; Wang, Z. Respiratory Pathogen Coinfection During Intersecting COVID-19 and Influenza Epidemics. Pathogens 2024, 13, 1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, C.; Zhou, A.; O’Brien, K.; Schmidt Arthur, R.; Geltz, J.; Shisler Joanna, L.; Schmidt Arthur, R.; Keefer, L.; Brown William, M.; Nguyen Thanh, H. Improved performance of nucleic acid-based assays for genetically diverse norovirus surveillance. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2023, 89, e00331-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Shen, Y.; Smith, R.L.; Dong, S.; Nguyen, T.H. Effect of disinfectant residuals on infection risks from Legionella pneumophila released by biofilms grown under simulated premise plumbing conditions. Environ. Int. 2020, 137, 105561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, F.; Su, L. CRISPR/Cas13a combined with reverse transcription and RPA for NoV GII.4 monitoring in water environments. Environ. Int. 2025, 195, 109195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weil, T.; Tighe, R.M.; Birnbaum, L.S. Beyond boundaries: The combined threats of air pollution and rising surface temperatures. Environ. Int. 2025, 204, 109841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, C.; Hu, Y.-n.; Gui, Z.-c.; Lai, T.-n.; Ali, W.; Wan, N.-h.; He, S.-s.; Liu, S.; Li, X.; Jin, T.-x.; et al. Quantitative SARS-CoV-2 exposure assessment for workers in wastewater treatment plants using Monte-Carlo simulation. Water Res. 2024, 248, 120845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rigaud, M.; Buekers, J.; Bessems, J.; Basagaña, X.; Mathy, S.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M.; Slama, R. The methodology of quantitative risk assessment studies. Environ. Health 2024, 23, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamilton, K.A.; Weir, M.H.; Haas, C.N. Dose response models and a quantitative microbial risk assessment framework for the Mycobacterium avium complex that account for recent developments in molecular biology, taxonomy, and epidemiology. Water Res. 2017, 109, 310–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Lin, B.; Wang, Y.; Shi, Y.; Zeng, W.; Zhao, Y.; Gu, Y.; Liu, C.; Gao, H.; Cheng, H.; et al. Multi-scenario surveillance of respiratory viruses in aerosols with sub-single-copy spatial resolution. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 8770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Huang, L.; Yan, J.; Zhang, H.; Jia, X.; Li, M.; Li, H. Artificial intelligence technology in environmental research and health: Development and prospects. Environ. Int. 2025, 203, 109788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassard, F.; Singh, S.; Coulon, F.; Yang, Z. Can wastewater monitoring protect public health in schools? Lancet Reg. Health—Am. 2023, 20, 100475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Li, D.; Coulon, F.; Yang, X.J. More work is needed to take on the rural wastewater challenge. Nature 2024, 628, 721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, Y.H.C.; Lau, E.H.Y.; Zhang, L.J.; Guan, Y.; Cowling, B.; Peiris, J.S.M. Avian Influenza and Ban on Overnight Poultry Storage in Live Poultry Markets, Hong Kong. Emerg. Infect. Dis. J. 2012, 18, 1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, H.; Wu, J.T.; Cowling, B.J.; Liao, Q.; Fang, V.J.; Zhou, S.; Wu, P.; Zhou, H.; Lau, E.H.Y.; Guo, D.; et al. Effect of closure of live poultry markets on poultry-to-person transmission of avian influenza A H7N9 virus: An ecological study. Lancet 2014, 383, 541–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Lu, J.; Sabino, E.; Zeng, X.; Song, Y.; Zou, L.; Yi, L.; Liang, L.; Ni, H.; Kang, M.; et al. Effect of Live Poultry Market Interventions on Influenza A(H7N9) Virus, Guangdong, China. Emerg. Infect. Dis. J. 2016, 22, 2104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filipić, A.; Dobnik, D.; Gutiérrez-Aguirre, I.; Ravnikar, M.; Košir, T.; Baebler, Š.; Štern, A.; Žegura, B.; Petkovšek, M.; Dular, M.; et al. Cold plasma within a stable supercavitation bubble—A breakthrough technology for efficient inactivation of viruses in water. Environ. Int. 2023, 182, 108285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, E.W.; Adcock, N.J.; Sivaganesan, M.; Brown, J.D.; Stallknecht, D.E.; Swayne, D.E. Chlorine Inactivation of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza Virus (H5N1). Emerg. Infect. Dis. J. 2007, 13, 1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lénès, D.; Deboosere, N.; Ménard-Szczebara, F.; Jossent, J.; Alexandre, V.; Machinal, C.; Vialette, M. Assessment of the removal and inactivation of influenza viruses H5N1 and H1N1 by drinking water treatment. Water Res. 2010, 44, 2473–2486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Z.; Li, M.; Zhang, Y.; Kong, L.; Smith, V.F.; Zhang, M.; Gulbrandson, A.J.; Waller, G.H.; Lin, F.; Liu, X.; et al. Fe–Fe Double-Atom Catalysts for Murine Coronavirus Disinfection: Nonradical Activation of Peroxides and Mechanisms of Virus Inactivation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 3804–3816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astrid, F.; Beata, Z.; Van den Nest, M.; Julia, E.; Elisabeth, P.; Magda, D.-E. The use of a UV-C disinfection robot in the routine cleaning process: A field study in an Academic hospital. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2021, 10, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casini, B.; Scarpaci, M.; Chiovelli, F.; Leonetti, S.; Costa, A.L.; Baroni, M.; Petrillo, M.; Cavallo, F. Antimicrobial efficacy of an experimental UV-C robot in controlled conditions and in a real hospital scenario. J. Hosp. Infect. 2025, 156, 72–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorca-Oró, C.; Vila, J.; Pleguezuelos, P.; Vergara-Alert, J.; Rodon, J.; Majó, N.; López, S.; Segalés, J.; Saldaña-Buesa, F.; Visa-Boladeras, M.; et al. Rapid SARS-CoV-2 Inactivation in a Simulated Hospital Room Using a Mobile and Autonomous Robot Emitting Ultraviolet-C Light. J. Infect. Dis. 2022, 225, 587–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morawska, L.; Allen, J.; Bahnfleth, W.; Bennett, B.; Bluyssen, P.M.; Boerstra, A.; Buonanno, G.; Cao, J.; Dancer, S.J.; Floto, A.; et al. Mandating indoor air quality for public buildings. Science 2024, 383, 1418–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, C.; Sun, P.P.; Araud, E.; Nguyen, T.H. Mechanism and efficacy of virus inactivation by a microplasma UV lamp generating monochromatic UV irradiation at 222 nm. Water Res. 2020, 186, 116386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takamure, K.; Iwatani, Y.; Amano, H.; Yagi, T.; Uchiyama, T. Inactivation characteristics of a 280 nm Deep-UV irradiation dose on aerosolized SARS-CoV-2. Environ. Int. 2023, 177, 108022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pi, S.-Y.; Wang, Y.; Lu, Y.-W.; Liu, G.-L.; Wang, D.-L.; Wu, H.-M.; Chen, D.; Liu, H. Fabrication of polypyrrole nanowire arrays-modified electrode for point-of-use water disinfection via low-voltage electroporation. Water Res. 2021, 207, 117825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowen, A.C.; Mubareka, S.; Steel, J.; Palese, P. Influenza Virus Transmission Is Dependent on Relative Humidity and Temperature. PLOS Pathog. 2007, 3, e151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaman, J.; Kohn, M. Absolute humidity modulates influenza survival, transmission, and seasonality. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 3243–3248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kormuth Karen, A.; Lin, K.; Qian, Z.; Myerburg Michael, M.; Marr Linsey, C.; Lakdawala Seema, S. Environmental Persistence of Influenza Viruses Is Dependent upon Virus Type and Host Origin. mSphere 2019, 4, e00552-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Sage, V.; Campbell, A.J.; Reed, D.; Duprex, W.P.; Lakdawala, S. Persistence of Influenza H5N1 and H1N1 Viruses in Unpasteurized Milk on Milking Unit Surfaces. Emerg. Infect. Dis. J. 2024, 30, 1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockey, N.C.; Le Sage, V.; Marr, L.C.; Lakdawala, S.S. Seasonal influenza viruses decay more rapidly at intermediate humidity in droplets containing saliva compared to respiratory mucus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2024, 90, e0201023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Z.; Morris, D.H.; Avery, A.; Kormuth, K.A.; Le Sage, V.; Myerburg, M.M.; Lloyd-Smith, J.O.; Marr, L.C.; Lakdawala, S.S. Variability in Donor Lung Culture and Relative Humidity Impact the Stability of 2009 Pandemic H1N1 Influenza Virus on Nonporous Surfaces. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2023, 89, e0063323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French, A.J.; Longest, A.K.; Pan, J.; Vikesland, P.J.; Duggal, N.K.; Marr, L.C.; Lakdawala, S.S. Environmental Stability of Enveloped Viruses Is Impacted by Initial Volume and Evaporation Kinetics of Droplets. mBio 2023, 14, e0345222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longest, A.K.; Rockey, N.C.; Lakdawala, S.S.; Marr, L.C. Review of factors affecting virus inactivation in aerosols and droplets. J. R. Soc. Interface 2024, 21, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Jin, Y.; Cui, H.; Wang, Z.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, L.; Song, S.; Lu, B.; Guo, Z. Cross-Species Transmission Risks of a Quail-Origin H7N9 Influenza Virus from China Between Avian and Mammalian Hosts. Viruses 2025, 17, 1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chong, K.C.; Zhao, S.; Hung, C.T.; Jia, K.M.; Ho, J.Y.-e.; Lam, H.C.Y.; Jiang, X.; Li, C.; Lin, G.; Yam, C.H.K.; et al. Association between meteorological variations and the superspreading potential of SARS-CoV-2 infections. Environ. Int. 2024, 188, 108762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Fu, Y.; Jia, R.; Guo, Z.; Su, C.; Li, J.; Zhao, X.; Jin, Y.; Li, P.; Fan, J.; et al. Visualization of the infection risk assessment of SARS-CoV-2 through aerosol and surface transmission in a negative-pressure ward. Environ. Int. 2022, 162, 107153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jin, Y.; Cui, H.; Jiang, L.; Li, L.; Zheng, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, H.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; et al. From Surfaces to Spillover: Environmental Persistence and Indirect Transmission of Influenza A(H3N8) Virus. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 2782. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122782

Jin Y, Cui H, Jiang L, Li L, Zheng J, Zhang Y, Wang H, Li Y, Wang Y, Zhao Y, et al. From Surfaces to Spillover: Environmental Persistence and Indirect Transmission of Influenza A(H3N8) Virus. Microorganisms. 2025; 13(12):2782. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122782

Chicago/Turabian StyleJin, Yifei, Huan Cui, Lina Jiang, Li Li, Jing Zheng, Yidun Zhang, Heng Wang, Yanrui Li, Yan Wang, Yixin Zhao, and et al. 2025. "From Surfaces to Spillover: Environmental Persistence and Indirect Transmission of Influenza A(H3N8) Virus" Microorganisms 13, no. 12: 2782. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122782

APA StyleJin, Y., Cui, H., Jiang, L., Li, L., Zheng, J., Zhang, Y., Wang, H., Li, Y., Wang, Y., Zhao, Y., Zhang, C., Yang, Z., Zhang, Y., & Wang, Z. (2025). From Surfaces to Spillover: Environmental Persistence and Indirect Transmission of Influenza A(H3N8) Virus. Microorganisms, 13(12), 2782. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122782