Morphological and Molecular Characterization of Cyanobacteria Isolated from Two Geothermal Springs of the Central Ecuadorian Andes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

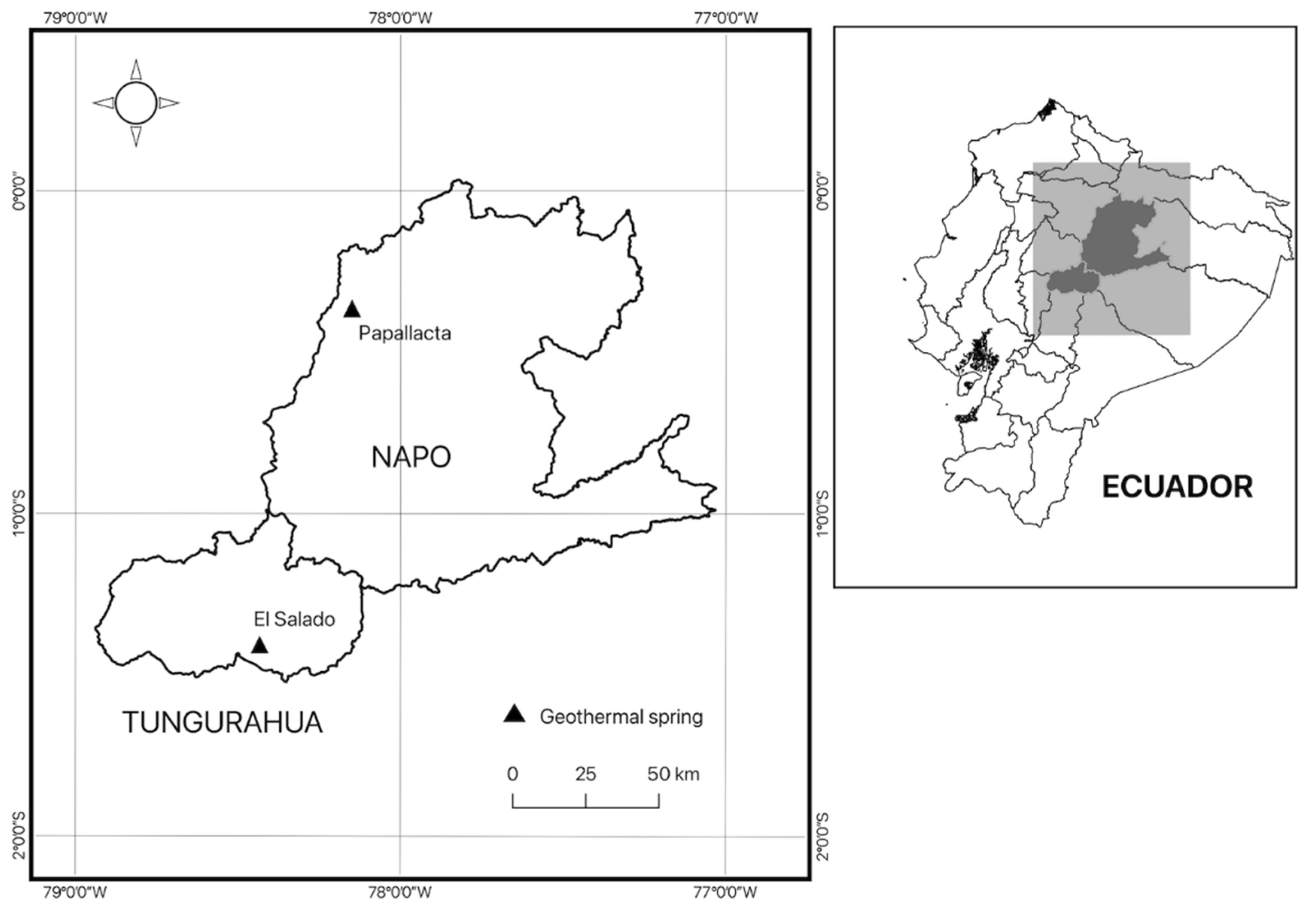

2.1. Sample Collection

2.2. Physicochemical Analysis

2.3. Isolation of Cyanobacteria and Morphological Identification

2.4. Molecular Analysis of Cyanobacterial Isolates

2.5. Phylogenetic Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Physicochemical Analysis of Hot Spring Waters

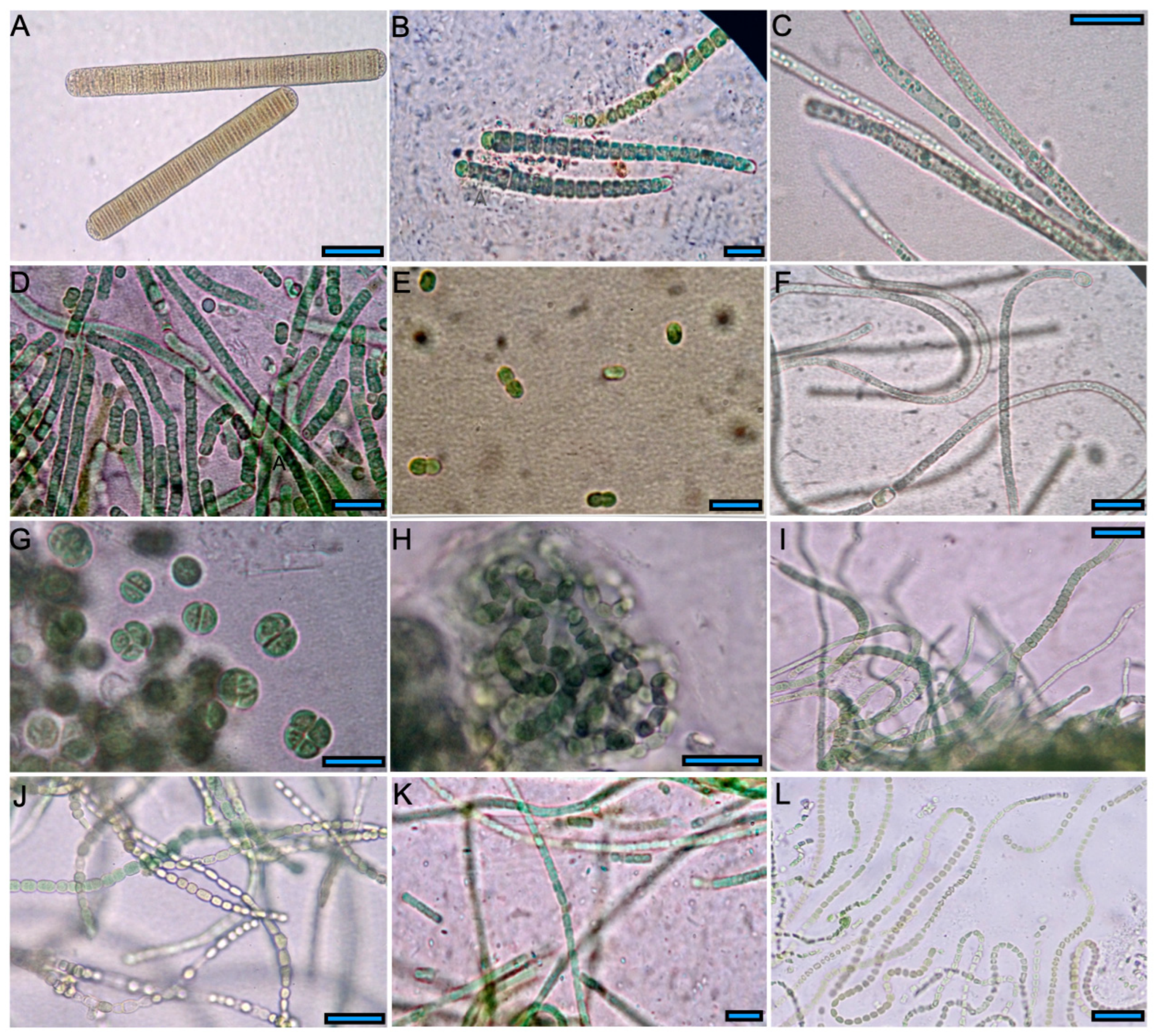

3.2. Isolation and Morphological Identification

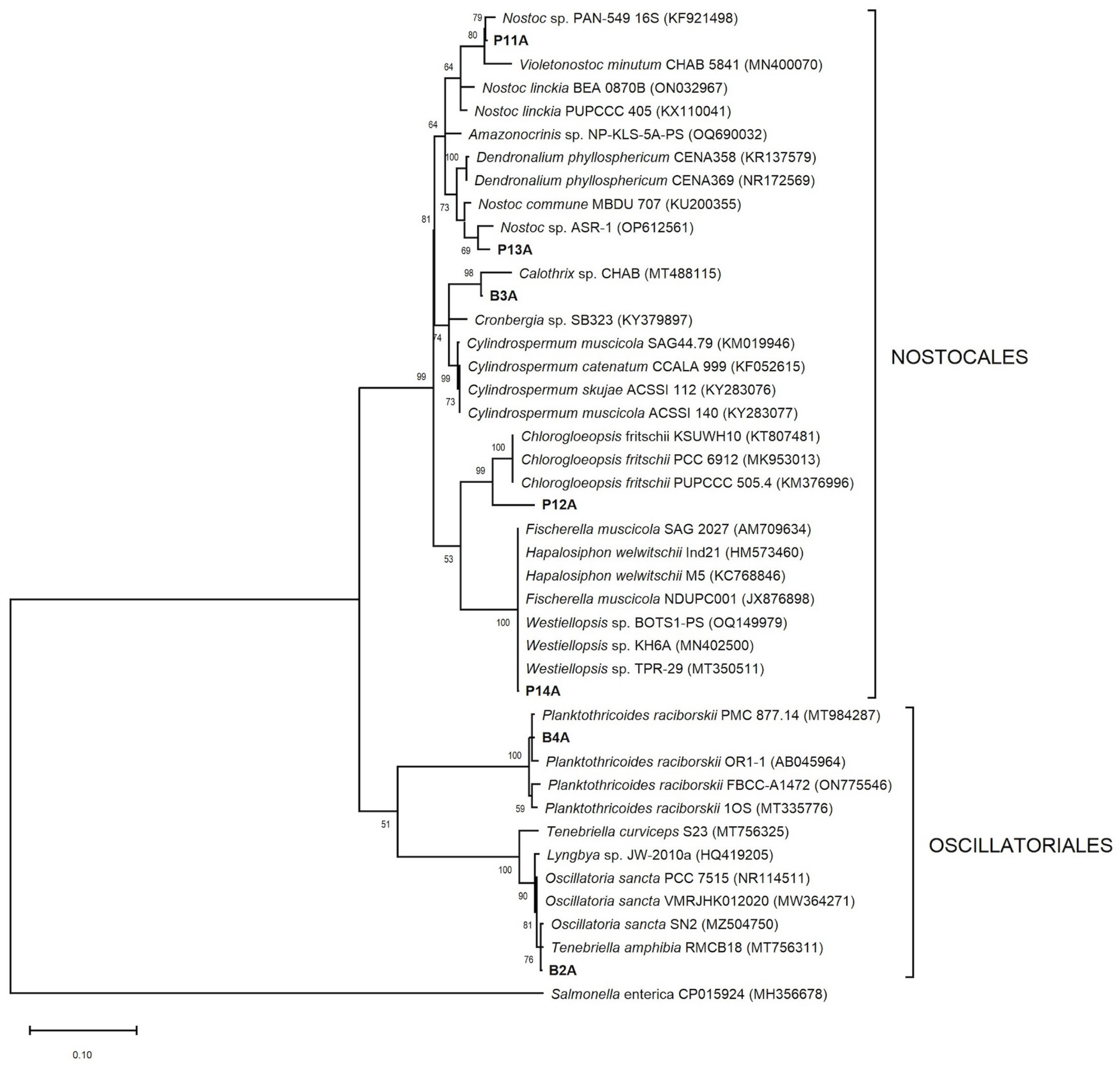

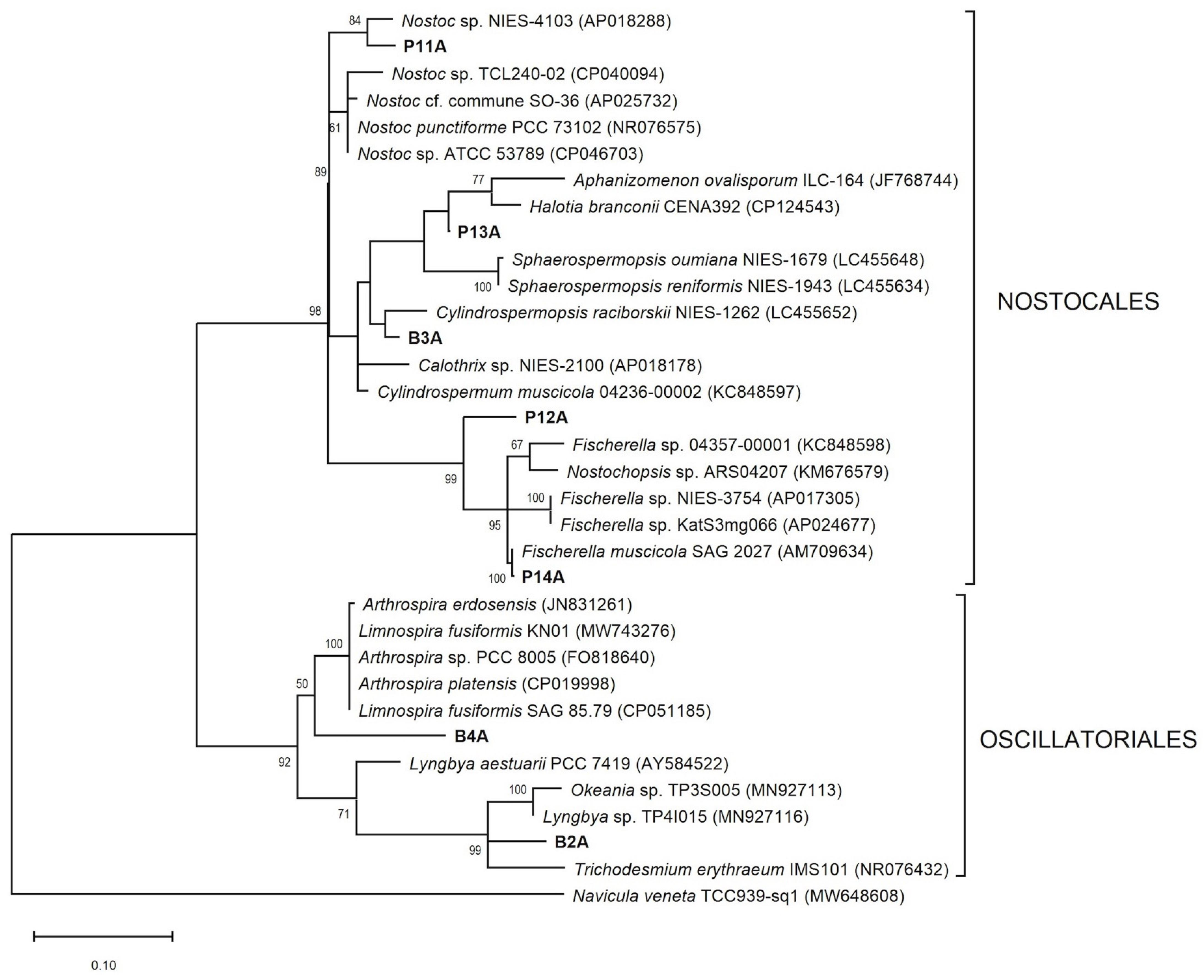

3.3. 16S and 23S rRNA Gen Phylogenetic Analysis

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Amarouche-Yala, S.; Benouadah, A.; El Ouahab Bentabet, A.; López-García, P. Morphological and Phylogenetic Diversity of Thermophilic Cyanobacteria in Algerian Hot Springs. Extremophiles 2014, 18, 1035–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Jiang, D.; Luo, Y.; Liang, Y.; Li, L.; Shah, M.M.R.; Daroch, M. Potential New Genera of Cyanobacterial Strains Isolated from Thermal Springs of Western Sichuan, China. Algal Res. 2018, 31, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheath, R.G.; Wehr, J.D. Chapter 1—Introduction to the Freshwater Algae. In Freshwater Algae of North America; Wehr, J.D., Sheath, R.G., Kociolek, J.P., Eds.; Aquatic Ecology; Academic Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2015; pp. 1–11. ISBN 978-0-12-385876-4. [Google Scholar]

- Ward, D.M.; Castenholz, R.W.; Miller, S.R. Cyanobacteria in Geothermal Habitats. In Ecology of Cyanobacteria II; Whitton, B.A., Ed.; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 39–63. [Google Scholar]

- Jasser, I.; Panou, M.; Khomutovska, N.; Sandzewicz, M.; Panteris, E.; Niyatbekov, T.; Łach, Ł.; Kwiatowski, J.; Kokociński, M.; Gkelis, S. Cyanobacteria in Hot Pursuit: Characterization of Cyanobacteria Strains, Including Novel Taxa, Isolated from Geothermal Habitats from Different Ecoregions of the World. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2022, 170, 107454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghozzi, K.; Zemzem, M.; Ben Dhiab, R.; Challouf, R.; Yahia, A.; Omrane, H.; Ben Ouada, H. Screening of Thermophilic Microalgae and Cyanobacteria from Tunisian Geothermal Sources. J. Arid Environ. 2013, 97, 14–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duval, C.; Hamlaoui, S.; Piquet, B.; Toutirais, G.; Yéprémian, C.; Reinhardt, A.; Duperron, S.; Marie, B.; Demay, J.; Bernard, C. Diversity of Cyanobacteria from Thermal Muds (Balaruc-Les-Bains, France) with the Description of Pseudochroococcus coutei Gen. Nov., Sp. Nov. FEMS Microbes 2021, 2, xtab006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ward, D.M.; Castenholz, R.W. Cyanobacteria in Geothermal Habitats. In The Ecology of Cyanobacteria: Their Diversity in Time and Space; Whitton, B.A., Potts, M., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2000; pp. 37–59. ISBN 978-0-306-46855-1. [Google Scholar]

- Castenholz, R.W. Portrait of a Geothermal Spring, Hunter’s Hot Springs, Oregon. Life 2015, 5, 332–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, Y.; Gulati, A.; Singh, D.P.; Khattar, J.I.S. Cyanobacterial Community Structure in Hot Water Springs of Indian North-Western Himalayas: A Morphological, Molecular and Ecological Approach. Algal Res. 2018, 29, 179–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, A.; Matsakas, L.; Rova, U.; Christakopoulos, P. A Perspective on Biotechnological Applications of Thermophilic Microalgae and Cyanobacteria. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 278, 424–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debnath, M.; Mandal, N.C.; Ray, S. The Study of Cyanobacterial Flora from Geothermal Springs of Bakreswar, West Bengal, India. Algae 2009, 24, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowange, R.W.T.M.R.T.K.; Jayasinghe, M.M.P.M.; Yakandawala, D.M.D.; Kumara, K.L.W.; Abeynayake, S.W.; Ratnayake, R.R. Morphological Characterization of Culturable Cyanobacteria Isolated from Selected Extreme Ecosystems of Sri Lanka. Ceylon J. Sci. 2022, 51, 577–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidari, F.; Zima, J.; Riahi, H.; Hauer, T. New Simple Trichal Cyanobacterial Taxa Isolated from Radioactive Thermal Springs. Fottea 2018, 18, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leu, J.-Y.; Lin, T.-H.; Selvamani, M.J.P.; Chen, H.-C.; Liang, J.-Z.; Pan, K.-M. Characterization of a Novel Thermophilic Cyanobacterial Strain from Taian Hot Springs in Taiwan for High CO2 Mitigation and C-Phycocyanin Extraction. Process Biochem. 2013, 48, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravakos, P.; Kotoulas, G.; Skaraki, K.; Pantazidou, A.; Economou-Amilli, A. A Polyphasic Taxonomic Approach in Isolated Strains of Cyanobacteria from Thermal Springs of Greece. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2016, 98, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strunecký, O.; Kopejtka, K.; Goecke, F.; Tomasch, J.; Lukavský, J.; Neori, A.; Kahl, S.; Pieper, D.H.; Pilarski, P.; Kaftan, D.; et al. High Diversity of Thermophilic Cyanobacteria in Rupite Hot Spring Identified by Microscopy, Cultivation, Single-Cell PCR and Amplicon Sequencing. Extremophiles 2019, 23, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sciuto, K.; Moro, I. Detection of the New Cosmopolitan Genus Thermoleptolyngbya (Cyanobacteria, Leptolyngbyaceae) Using the 16S RRNA Gene and 16S–23S ITS Region. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2016, 105, 15–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rupasinghe, R.; Amarasena, S.; Wickramarathna, S.; Biggs, P.J.; Chandrajith, R.; Wickramasinghe, S. Microbial Diversity and Ecology of Geothermal Springs in the High-Grade Metamorphic Terrain of Sri Lanka. Environ. Adv. 2022, 7, 100166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abed, R.M.M.; Dobretsov, S.; Sudesh, K. Applications of Cyanobacteria in Biotechnology. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2009, 106, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martineau, E.; Wood, S.A.; Miller, M.R.; Jungblut, A.D.; Hawes, I.; Webster-Brown, J.; Packer, M.A. Characterisation of Antarctic Cyanobacteria and Comparison with New Zealand Strains. Hydrobiologia 2013, 711, 139–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sciuto, K.; Andreoli, C.; Rascio, N.; La Rocca, N.; Moro, I. Polyphasic Approach and Typification of Selected Phormidium Strains (Cyanobacteria). Cladistics 2012, 28, 357–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komárek, J. A Polyphasic Approach for the Taxonomy of Cyanobacteria: Principles and Applications. Eur. J. Phycol. 2016, 51, 346–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherwood, A.R.; Presting, G.G. Universal Primers Amplify a 23S RDNA Plastid Marker in Eukaryotic Algae and Cyanobacteria. J. Phycol. 2007, 43, 605–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toulkeridis, T.; Zach, I. Wind Directions of Volcanic Ash-Charged Clouds in Ecuador—Implications for the Public and Flight Safety. Geomat. Nat. Hazards Risk 2017, 8, 242–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inguaggiato, S.; Hidalgo, S.; Beate, B.; Bourquin, J. Geochemical and Isotopic Characterization of Volcanic and Geothermal Fluids Discharged from the Ecuadorian Volcanic Arc. Geofluids 2010, 10, 525–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burbano, N.; Becerra, S.; Pasquel, E. Aguas Termo Minerales En El Ecuador. Inst. Nac. Meteorol. E Hidrol. (INAMHI) 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Jara-Alvear, J.; De Wilde, T.; Asimbaya, D.; Urquizo, M.; Ibarra, D.; Graw, V.; Guzmán, P. Geothermal Resource Exploration in South America Using an Innovative GIS-Based Approach: A Case Study in Ecuador. J. S. Am. Earth Sci. 2023, 122, 104156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, E.D.; Luna, V.; Navarro, L.; Santana, V.; Gordillo, A.; Arévalo, A. Diversidad de Microalgas y Cianobacterias En Muestras Provenientes de Diferentes Provincias Del Ecuador, Destinadas a Una Colección de Cultivos. Rev. Ecuat. Med. Cienc. Biol. 2013, 34, 129–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivas-Párraga, R.; Izquierdo, A.; Sánchez, K.; Bolaños-Guerrón, D.; Alfaro-Núñez, A. Identification and Phylogenetic Characterization Based on DNA Sequences from RNA Ribosomal Genes of Thermophilic Microorganisms in a High Elevation Andean Tropical Geothermal Spring. Rev. Bionatura 2022, 7, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komárek, J.; Kaštovský, J.; Mareš, J.; Johansen, J.R. Taxonomic Classification of Cyanoprokaryotes (Cyanobacterial Genera) 2014, Using a Polyphasic Approach. Preslia 2014, 86, 295–335. [Google Scholar]

- Komárek, J.; Anagnostidis, K. Cyanoprokaryota II. In Süsswasserflora von Mittleuropa, Bd 19/2; Büdel, B., Krienitz, L., Gärtner, G., Schagerl, M., Eds.; Elsevier/Spektrum: München, Germany, 2005; p. 759. [Google Scholar]

- Komárek, J. Cyanoprokaryota 3. Teil/3rd Part: Heterocytous Genera. In Süßwasserflora von Mitteleuropa, Bd. 19/3; Büdel, B., Gärtner, G., Krienitz, L., Schagerl, M., Eds.; Springer: Spektrum, Germany, 2013; p. 1131. [Google Scholar]

- Anagnostidis, K.; Komárek, J. Modern Approach to the Classification System of Cyanophytes. 3—Oscillatoriales. Arch. Hydrobiol. Suppl. Algol. Stud. 1988, 50–53, 327–472. [Google Scholar]

- Anagnostidis, K. Nomenclatural Changes in Cyanoprokaryotic Order Oscillatoriales. Preslia 2001, 73, 359–375. [Google Scholar]

- Guiry, M.D.; Guiry, G.M. AlgaeBase. Available online: https://www.algaebase.org (accessed on 14 February 2023).

- Cai, Y.P.; Wolk, C.P. Use of a Conditionally Lethal Gene in Anabaena sp. Strain PCC 7120 to Select for Double Recombinants and to Entrap Insertion Sequences. J. Bacteriol. 1990, 172, 3138–3145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felföldi, T.; Somogyi, B.; Márialigeti, K.; Vörös, L. Characterization of Photoautotrophic Picoplankton Assemblages in Turbid, Alkaline Lakes of the Carpathian Basin (Central Europe). J. Limnol. 2009, 68, 385–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kearse, M.; Moir, R.; Wilson, A.; Stones-Havas, S.; Cheung, M.; Sturrock, S.; Buxton, S.; Cooper, A.; Markowitz, S.; Duran, C.; et al. Geneious Basic: An Integrated and Extendable Desktop Software Platform for the Organization and Analysis of Sequence Data. Bioinformatics 2012, 28, 1647–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altschul, S.F.; Gish, W.; Miller, W.; Myers, E.W.; Lipman, D.J. Basic Local Alignment Search Tool. J. Mol. Biol. 1990, 215, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edgar, R.C. MUSCLE: Multiple Sequence Alignment with High Accuracy and High Throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004, 32, 1792–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Kumar, S. MEGA11: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 11. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021, 38, 3022–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castresana, J. Selection of Conserved Blocks from Multiple Alignments for Their Use in Phylogenetic Analysis. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2000, 17, 540–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Churro, C.; Semedo-Aguiar, A.P.; Silva, A.D.; Pereira-Leal, J.B.; Leite, R.B. A Novel Cyanobacterial Geosmin Producer, Revising GeoA Distribution and Dispersion Patterns in Bacteria. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 8679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finsinger, K.; Scholz, I.; Serrano, A.; Morales, S.; Uribe-Lorio, L.; Mora, M.; Sittenfeld, A.; Weckesser, J.; Hess, W.R. Characterization of True-Branching Cyanobacteria from Geothermal Sites and Hot Springs of Costa Rica. Environ. Microbiol. 2008, 10, 460–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alcorta, J.; Espinoza, S.; Viver, T.; Alcamán-Arias, M.E.; Trefault, N.; Rosselló-Móra, R.; Díez, B. Temperature Modulates Fischerella thermalis Ecotypes in Porcelana Hot Spring. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 2018, 41, 531–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaštovský, J.; Johansen, J.R. Mastigocladus laminosus (Stigonematales, Cyanobacteria): Phylogenetic Relationship of Strains from Thermal Springs to Soil-Inhabiting Genera of the Order and Taxonomic Implications for the Genus. Phycologia 2008, 47, 307–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirose, Y.; Fujisawa, T.; Ohtsubo, Y.; Katayama, M.; Misawa, N.; Wakazuki, S.; Shimura, Y.; Nakamura, Y.; Kawachi, M.; Yoshikawa, H.; et al. Complete Genome Sequence of Cyanobacterium Fischerella Sp. NIES-3754, Providing Thermoresistant Optogenetic Tools. J. Biotechnol. 2016, 220, 45–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kato, S.; Masuda, S.; Shibata, A.; Shirasu, K.; Ohkuma, M. Insights into Ecological Roles of Uncultivated Bacteria in Katase Hot Spring Sediment from Long-Read Metagenomics. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 1045931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casamatta, D.A.; Villanueva, C.D.; Garvey, A.D.; Stocks, H.S.; Vaccarino, M.; Dvořák, P.; Hašler, P.; Johansen, J.R. Reptodigitus Chapmanii (Nostocales, Hapalosiphonaceae) Gen. Nov.: A Unique Nostocalean (Cyanobacteria) Genus Based on a Polyphasic Approach1. J. Phycol. 2020, 56, 425–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gugger, M.F.; Hoffmann, L. Polyphyly of True Branching Cyanobacteria (Stigonematales). Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2004, 54, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishida, T.; Watanabe, M.M.; Sugiyama, J.; Yokota, A. Evidence for Polyphyletic Origin of the Members of the Orders of Oscillatoriales and Pleurocapsales as Determined by 16S RDNA Analysis. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2001, 201, 79–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Jia, N.; Geng, R.; Yu, G.; Li, R. Phylogenetic Insights into Chroococcus-like Taxa (Chroococcales, Cyanobacteria), Describing Cryptochroococcus tibeticus Gen. Nov. Sp. Nov. and Limnococcus fonticola Sp. Nov. from Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. J. Phycol. 2021, 57, 1739–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarenga, D.O.; Andreote, A.P.D.; Branco, L.H.Z.; Delbaje, E.; Cruz, R.B.; Varani, A.d.M.; Fiore, M.F. Amazonocrinis Nigriterrae Gen. Nov., Sp. Nov., Atlanticothrix silvestris Gen. Nov., Sp. Nov. and Dendronalium phyllosphericum Gen. Nov., Sp. Nov., Nostocacean Cyanobacteria from Brazilian Environments. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2021, 71, 004811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Genuário, D.B.; Vieira Vaz, M.G.M.; Hentschke, G.S.; Sant’Anna, C.L.; Fiore, M.F. Halotia Gen. Nov., a Phylogenetically and Physiologically Coherent Cyanobacterial Genus Isolated from Marine Coastal Environments. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2015, 65, 633–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadheech, P.K.; Glöckner, G.; Casper, P.; Kotut, K.; Mazzoni, C.J.; Mbedi, S.; Krienitz, L. Cyanobacterial Diversity in the Hot Spring, Pelagic and Benthic Habitats of a Tropical Soda Lake. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2013, 85, 389–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pentecost, A. Cyanobacteria Associated with Hot Spring Travertines. Can. J. Earth Sci. 2003, 40, 1447–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauerová, R.; Hauer, T.; Kaštovský, J.; Komárek, J.; Lepšová-Skácelová, O.; Mareš, J. Tenebriella Gen. Nov.—The Dark Twin of Oscillatoria. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2021, 165, 107293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, P.; Satpati, G.G.; Öztürk, S.; Gupta, R.K. Taxonomic and Ecological Aspects of Thermophilic Cyanobacteria from Some Geothermal Springs of Jharkhand and Bihar, India. Egypt. J. Bot. 2023, 63, 315–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith-Bädorf, H.D.; Chuck, C.J.; Mokebo, K.R.; MacDonald, H.; Davidson, M.G.; Scott, R.J. Bioprospecting the Thermal Waters of the Roman Baths: Isolation of Oleaginous Species and Analysis of the FAME Profile for Biodiesel Production. AMB Express 2013, 3, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiore, M.F.; Moon, D.H.; Tsai, S.M.; Lee, H.; Trevors, J.T. Miniprep DNA Isolation from Unicellular and Filamentous Cyanobacteria. J. Microbiol. Methods 2000, 39, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.P.; Rastogi, R.P.; Häder, D.-P.; Sinha, R.P. An Improved Method for Genomic DNA Extraction from Cyanobacteria. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2011, 27, 1225–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGregor, G.B.; Rasmussen, J.P. Cyanobacterial Composition of Microbial Mats from an Australian Thermal Spring: A Polyphasic Evaluation. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2008, 63, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wehr, J.D.; Sheath, R.G. Chapter 2—Habitats of Freshwater Algae. In Freshwater Algae of North America; Wehr, J.D., Sheath, R.G., Kociolek, J.P., Eds.; Aquatic Ecology; Academic Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2015; pp. 13–74. ISBN 978-0-12-385876-4. [Google Scholar]

- Beate, B.; Salgado, R. Geothermal Country Update for Ecuador, 2000–2005. In Proceedings of the World Geothermal Congress, Antalya, Turkey, 24–29 April 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Carrera-Villacrés, D.; Guevara-García, P.; Hidalgo-Hidalgo, A.; Teresa-Vivero, M.; Maya-Carrillo, M. Removal of Physical Information Chemistry of Spa That Is Utilizing Geothermal Water in Ecuador. Procedia Earth Planet. Sci. 2015, 15, 367–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Strazzulli, A.; Fusco, S.; Cobucci-Ponzano, B.; Moracci, M.; Contursi, P. Metagenomics of Microbial and Viral Life in Terrestrial Geothermal Environments. Rev. Environ. Sci. Biotechnol. 2017, 16, 425–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oren, A.; Ionescu, D.; Hindiyeh, M.Y.; Malkawi, H.I. Morphological, Phylogenetic and Physiological Diversity of Cyanobacteria in the Hot Springs of Zerka Ma. BioRisk 2009, 3, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Forlani, G.; Pavan, M.; Gramek, M.; Kafarski, P.; Lipok, J. Biochemical Bases for a Widespread Tolerance of Cyanobacteria to the Phosphonate Herbicide Glyphosate. Plant Cell Physiol. 2008, 49, 443–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bywaters, K.F.; Fritsen, C.H. Biomass and Neutral Lipid Production in Geothermal Microalgal Consortia. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2015, 2, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyairi, S. CO2 Assimilation in a Thermophilic Cyanobacterium. Energy Convers. Manag. 1995, 36, 763–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatay, S.E.; Dönmez, G. Microbial Oil Production from Thermophile Cyanobacteria for Biodiesel Production. Appl. Energy 2011, 88, 3632–3635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslova, I.P.; Mouradyan, E.A.; Lapina, S.S.; Klyachko-Gurvich, G.L.; Los, D.A. Lipid Fatty Acid Composition and Thermophilicity of Cyanobacteria. Russ. J. Plant Physiol. 2004, 51, 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadettin, S.; Dönmez, G. Bioaccumulation of Reactive Dyes by Thermophilic Cyanobacteria. Process Biochem. 2006, 41, 836–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishioka, M.; Nishiuma, H.; Miyake, M.; Asada, Y.; Shimizu, K.; Taya, M. Metabolic Flux Analysis of a Poly-β-Hydroxybutyrate Producing Cyanobacterium,Synechococcus sp. MA19, Grown under Photoautotrophic Conditions. Biotechnol. Bioprocess Eng. 2002, 7, 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishioka, M.; Nakai, K.; Miyake, M.; Asada, Y.; Taya, M. Production of Poly-β-Hydroxybutyrate by Thermophilic Cyanobacterium, Synechococcus sp. MA19, under Phosphate-Limited Conditions. Biotechnol. Lett. 2001, 23, 1095–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyake, M.; Erata, M.; Asada, Y. A Thermophilic Cyanobacterium, Synechococcus sp. MA19, Capable of Accumulating Poly-β-Hydroxybutyrate. J. Ferment. Bioeng. 1996, 82, 512–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Castillo, D.; Arroyo, G.; Escorza, J.; Angulo, Y.; Debut, A.; Vizuete, K.; Izquierdo, A.; Arias, M. Development of a Hybrid Cell for Energy Production. Nanotechnology 2021, 32, 415401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arroyo, G.; Angulo, Y.; Naranjo, B.; Toscano, F.; Arias, M.T.; Debut, A.; Reinoso, C.; Stael, C.; Soria, J.; Izquierdo, A. Green Synthesis of Antioxidant and Low-Toxicity Gold and Silver Nanoparticles Using Floral Extracts. OpenNano 2025, 26, 100258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameters | El Salado | Papallacta |

|---|---|---|

| Temperature (°C) | 45–48 | 50–54 |

| pH | 6.3–6.6 | 7.0–7.5 |

| Electrical conductivity (μS/cm) | 6850 | 2080 |

| Cl− (mg/L) | 898 | 404 |

| SO4−2 (mg/L) | >700 | 38.4 |

| Na+ (mg/L) | >10 | 138.6 |

| K+ (mg/L) | >100 | 11.4 |

| Ca++ (mg/L) | >50 | 158.4 |

| Mg++ (mg/L) | >12 | 1.9 |

| Arsenic (mg/L) | 0.2440 | 0.686 |

| Copper (mg/L) | <0.05 | <0.020 |

| Iron (mg/L) | 8 | <0.050 |

| Manganese (mg/L) | 0.5 | 0.017 |

| Total alkalinity (mg/L) | >1000 | 71 |

| Settleable solids (mL/L) | <0.1 | <5.0 |

| Total solids (mg/L) | >2000 | 1522 |

| Strain Code/ | Identification | Vegetative Cells | Heterocyst | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Location | N | Width (µm) | Length (µm) | N | Width (µm) | Length (µm) | |

| B2A El Salado |

Tenebriella

amphibia | 30 | 14.2–19.4 | 0.1–4.0 | – | – | |

| (16.4 ± 1.5) | (1.5 ± 1.1) | ||||||

| B3A El Salado | Calothrix sp. | 30 | 1.3–7.9 | 2.7–11.5 | 15 | 3.3–9.5 | 1.7–9.4 |

| (5.2 ± 2) | (7.0 ± 2.7) | (5.1 ± 1.7) | (3.8 ± 2.4) | ||||

| B4A a El Salado | Planktothricoides sp. a | 30 | 2.4–5.9 | – | – | – | |

| (4.4 ± 0.7) | |||||||

| B5A El Salado | Leptolyngbya sp. | 30 | 1.4–3.8 | 1.5–3.5 | – | – | |

| (2.5 ± 0.6) | (2.5 ± 0.6) | ||||||

| B6A El Salado | Synechococcus sp. | 15 | 3.1–4.3 | 5.2–10.2 | – | – | |

| (3.8 ± 0.4) | (6.7 ± 1.4) | ||||||

| P11A Papallacta | Nostoc sp. | 30 | 3.9–5.8 | 2.8–7.8 | 15 | 6.5–9.1 | 8.0–13.0 |

| (4.7 ± 0.6) | (5.8 ± 1.5) | (7.6 ± 0.7) | (10.5 ± 1.6) | ||||

| P12A Papallacta | Chroococcales | 15 | 9.8–16.4 | 9.9–17.1 | – | – | |

| (12.3 ± 2.3) | (12.8 ± 2.2) | ||||||

| P13A Papallacta | Nostocales | 30 | 3.2–5.9 | 2.7–6.0 | 15 | 2.1–4.0 | 3.0–4.5 |

| (4.4 ± 0.8) | (3.9 ± 0.8) | (3.4 ± 0.6) | (3.9 ± 0.5) | ||||

| P14A Papallacta | Fischerella sp. | 30 | 2.7–5.8 | 3.5–8.1 | 7 | 3.8–5.1 | 4.5–6.8 |

| (4.3 ± 0.8) | (5.2 ± 1.2) | (4.5 ± 0.4) | (5.2 ± 0.7) | ||||

| P15A Papallacta | Leptolyngbya sp. | 30 | 1.5–3.0 | 1.0–3.3 | – | – | |

| (2.3 ± 0.3) | (2.5 ± 0.6) | ||||||

| P38A Papallacta | Komvophoron jovis | 30 | 1.6–4.7 | 1.8–4.3 | – | – | |

| (2.7 ± 0.9) | (3.2 ± 0.6) | ||||||

| Molecular Identification | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16S rRNA | 23S rRNA | |||||

| Strain Code | Morphological Identification | Access. No. (Fragment Length bp) | Highest Blast Match (Access. No.) (Identity %) | Access. No. (Fragment Length bp) | Highest Blast Match (Access. No.) (Identity %) | Taxonomic Assignment |

| B2A |

Tenebriella

amphibia | MH090926 (631) | Tenebriella amphibia RMCB18 (MT756311) (99.8) | MH101455 (332) | Trichodesmium erythraeum IMS101 (NR076432) (92.5) | Tenebriella amphibia |

| B3A | Calothrix sp. | MH090927 (630) | Calothrix sp. CHAB TP201528 (MT488122) (97.8) | MH101456 (377) | Cylindrospermopsis raciborskii NIES-1262 (LC455652) (96.8) | Calothrix sp. |

| B4A | Planktothricoides sp. | MH090928 (629) | Planktothricoides raciborskii PMC 877.14 (MT984287) (99.8) | MH101457 (390) | Limnospira fusiformis SAG 85.79 (CP051185) (92.3) | Planktothricoides raciborskii |

| P11A | Nostoc sp. | MH090929 (619) | Nostoc sp. PAN-549 (KF921498) (99.2) | MH101458 (379) | Nostoc sp. NIES-4103 (AP018288) (96.3) | Nostoc sp. |

| P12A | Chroococcales | MH090931 (632) | Chlorogloeopsis fritschii PCC 6912 (MK953013) (95.9) | MH101459 (379) | Fischerella muscicola SAG 2027 (AM709634) (94.5) | Chroococcalean cyanobacterium |

| P13A | Nostocales | MH090930 (633) | Dendronalium phyllosphericum CENA369 (NR172569) (98.2) | MH101460 (393) | Halotia branconii CENA392 (CP124543) (96.7) | Nostocacean cyanobacterium |

| P14A | Fischerella sp. | MH090932 (622) | Fischerella muscicola NDUPC001 (JX876898) (100) | MH101461 (378) | Fischerella muscicola SAG 2027 (AM709634) (99.5) | Fischerella muscicola |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Naranjo, R.E.; Izquierdo, A. Morphological and Molecular Characterization of Cyanobacteria Isolated from Two Geothermal Springs of the Central Ecuadorian Andes. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 2763. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122763

Naranjo RE, Izquierdo A. Morphological and Molecular Characterization of Cyanobacteria Isolated from Two Geothermal Springs of the Central Ecuadorian Andes. Microorganisms. 2025; 13(12):2763. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122763

Chicago/Turabian StyleNaranjo, Renato E., and Andrés Izquierdo. 2025. "Morphological and Molecular Characterization of Cyanobacteria Isolated from Two Geothermal Springs of the Central Ecuadorian Andes" Microorganisms 13, no. 12: 2763. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122763

APA StyleNaranjo, R. E., & Izquierdo, A. (2025). Morphological and Molecular Characterization of Cyanobacteria Isolated from Two Geothermal Springs of the Central Ecuadorian Andes. Microorganisms, 13(12), 2763. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122763