Proactive Strategies to Prevent Biofilm-Associated Infections: From Mechanistic Insights to Clinical Translation

Abstract

1. Introduction

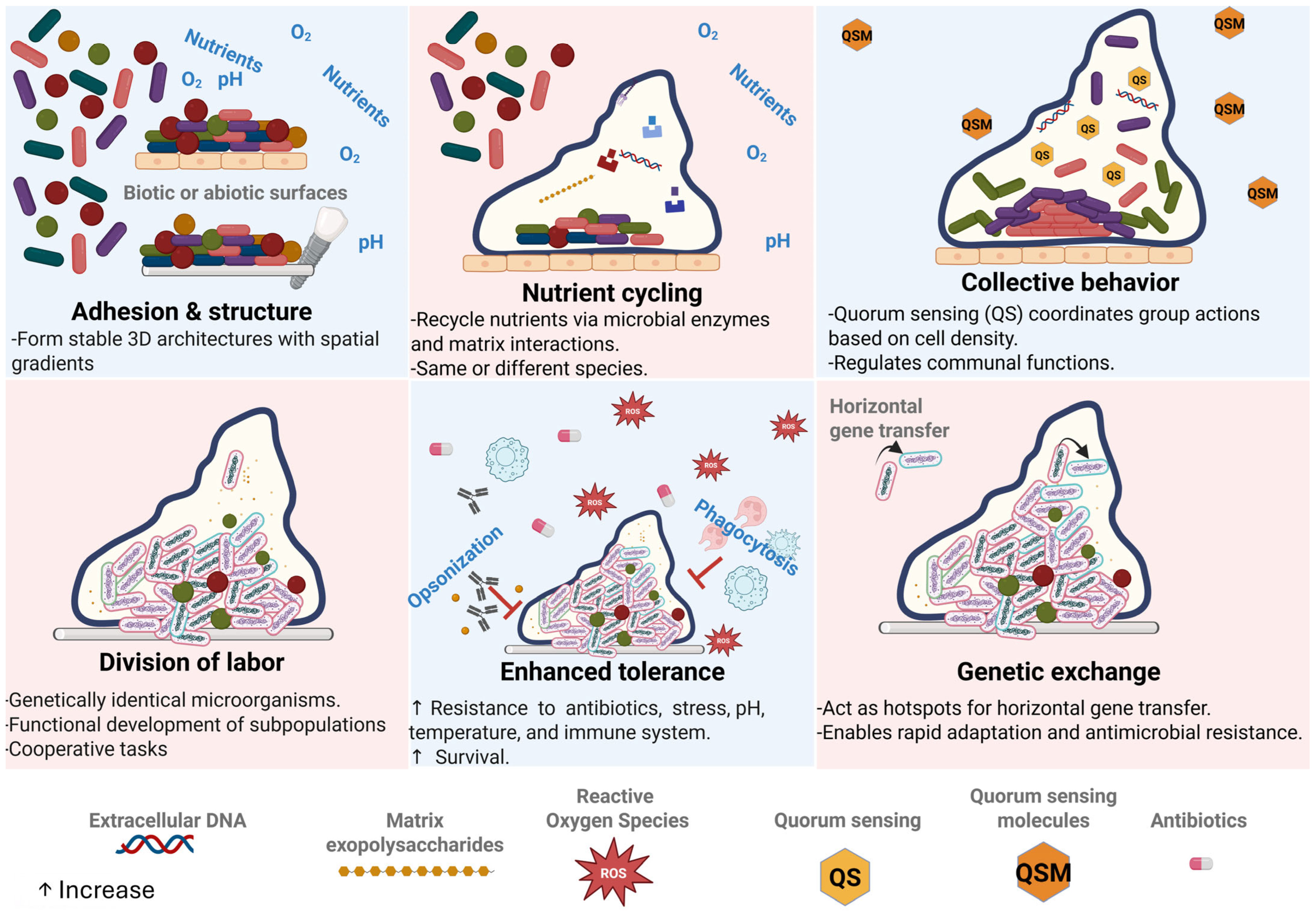

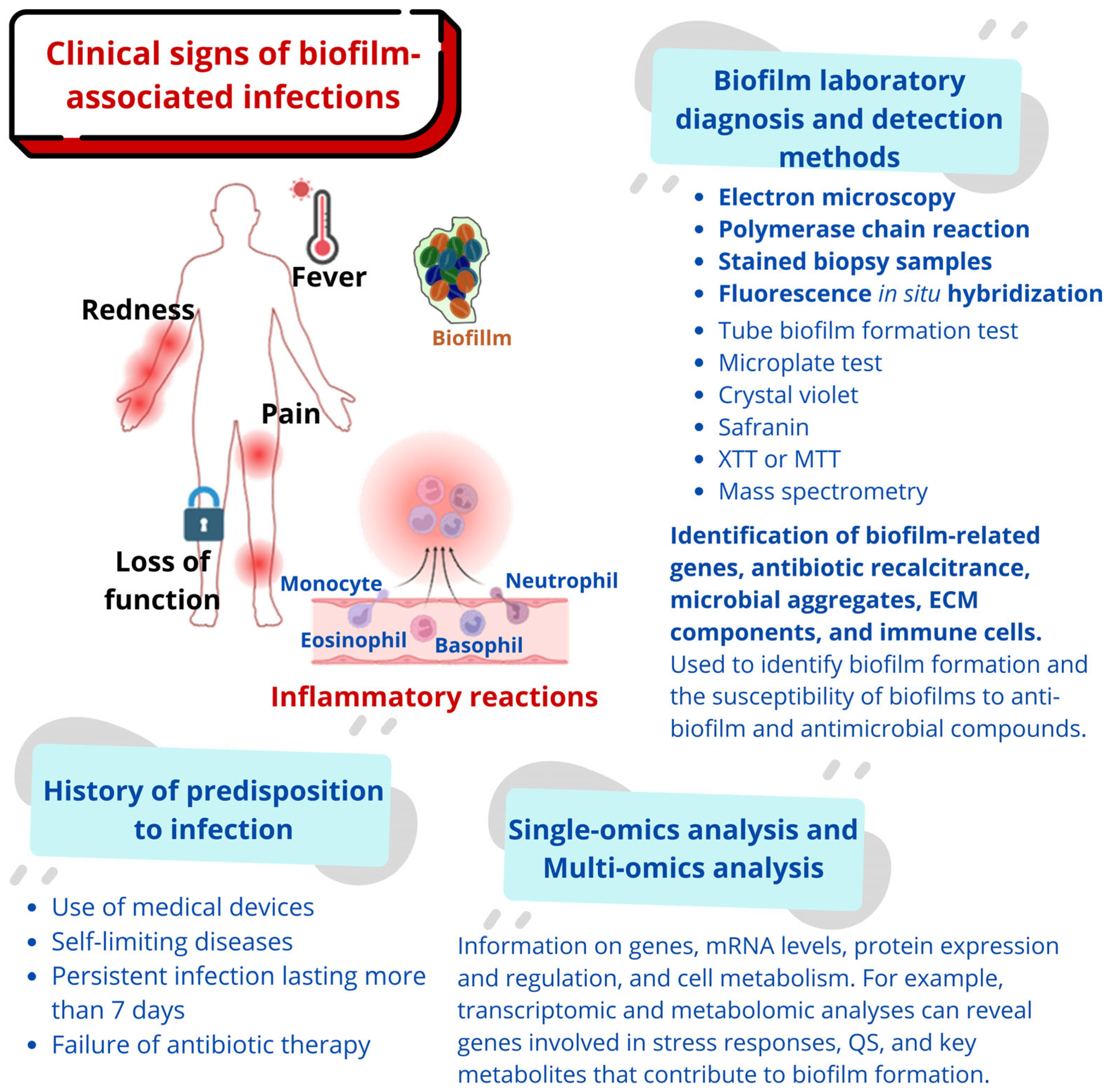

2. The Clinical Challenge of Biofilm

3. Immune Response to Biofilms

4. Hormonal Modulation of Biofilm Formation: Endocrine, Metabolic, and Immune Interplay

4.1. Endocrine Regulation: Hormones as Biofilm Modulators

4.2. Metabolic Context: Biofilms at the Crossroads of Glucose, Insulin, and Metabolism

4.3. Immune Interface: Hormonal Modulation of Host–Biofilm Immune Dynamics

4.4. Targeted Strategy Against Biofilms Using Hormonal and Metabolic Controllers

5. Emerging Biofilm Prevention Strategies

| Emerging Strategy | Mechanism of Action | Advantages | Limitations | Clinical/Practical Applications | Examples/Notes | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SACs | Release of antimicrobials or reactive agents in response to microbial signals | High specificity; activity triggered only when bacteria are present | High production cost; potential cytotoxicity | Catheters, endotracheal tubes, orthopedic implants, wound dressings | Light-activated coatings, antibiotic-eluting polymers | [67,68] |

| MDEs | Enzymatic degradation of EPS components (DNA, proteins, PS) | Enhances antibiotic penetration and disrupts mature biofilms | Limited stability; immunogenicity concerns | Wound care, infected implants, chronic ulcers | DNase I, dispersin B, proteinase K, subtilisin | [69,70,71,72] |

| QSIs | Block communication signals required for adhesion, maturation, and virulence | Low likelihood of resistance; targets early biofilm formation | Limited commercial availability; variable efficacy | Prevention of device-associated infections; coatings; topical applications | Synthetic furanones, ajoene, and plant-derived inhibitors | [73,74,75] |

| Functionalized NPs | Disrupt bacterial membranes; generate ROS; penetrate biofilm matrix | Potent against MDR organisms; broad-spectrum | Potential toxicity; environmental accumulation | Antimicrobial catheters, dental materials, and topical antimicrobials | Ag-S-1, AgNPs + Ca(OH)2 | [76,77,78,79,80] |

| Engineered Bacteriophages | Target and lyse specific biofilm-forming bacteria; self-amplifying | High specificity; active in dense biofilms | Regulatory challenges; narrow host range | Chronic device-related infections; wound therapy | Phage cocktails, engineered biofilm-penetrating phages | [81,82] |

| AMPs | Disrupt bacterial membranes; inhibit adhesion | Low resistance potential; broad-spectrum | Degradation in physiological environments | Coatings for implants, topical gels, and catheter lock solutions | Melittin, LL-37, indolicidin | [83,84,85] |

| Anti-Adhesive Surface Modification | Alters physicochemical properties to prevent bacterial attachment | Prevents early colonization without antibiotics | Ineffective once biofilm forms | Titanium implants, dental implants, vascular grafts | PEGylation, zwitterionic coatings, plasma-treated surfaces | [86,87,88] |

| Probiotics and Competitive Exclusion | Occupy niches and inhibit pathogens through competition and metabolite secretion | Safe, biocompatible; modulates microbiome | Requires sustained application; strain-dependent efficacy | Urogenital/gastrointestinal mucosa, oral cavity | Lactobacillus spp., Bacillus subtilis | [89,90,91] |

6. Limitations

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AgNPs | Silver Nanoparticles |

| AMPs | Calcium Hydroxide |

| c-di-GMP | Cyclic Dimeric Guanosine Monophosphate |

| EPS | Extracellular Polymeric Substances |

| MTT | 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide |

| PEEK | Polyetheretherketone |

| PEG | Polyethylene Glycol |

| QS | Quorum Sensing |

| QSIs | Quorum Sensing Inhibitors/Quorum Sensing Interference |

| SCFAs | Short-chain fatty acids |

| TLR | Toll-Like Receptor |

| XTT | 2,3-bis(2-methoxy-4-nitro-5-sulfophenyl)-5-[(phenylamino)carbonyl]-2H-tetrazolium hydroxide |

References

- Bamford, N.C.; MacPhee, C.E.; Stanley-Wall, N.R. Microbial Primer: An introduction to biofilms—What they are, why they form and their impact on built and natural environments. Microbiology 2023, 169, 001338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flemming, H.C.; van Hullebusch, E.D.; Neu, T.R.; Nielsen, P.H.; Seviour, T.; Stoodley, P.; Wingender, J.; Wuertz, S. The biofilm matrix: Multitasking in a shared space. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2023, 21, 70–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall-Stoodley, L.; Costerton, J.W.; Stoodley, P. Bacterial biofilms: From the natural environment to infectious diseases. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2004, 2, 95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nadell, C.D.; Xavier, J.B.; Foster, K.R. The sociobiology of biofilms. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2009, 33, 206–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madsen, J.S.; Burmølle, M.; Hansen, L.H.; Sørensen, S.J. The interconnection between biofilm formation and horizontal gene transfer. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 2012, 65, 183–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battin, T.J.; Besemer, K.; Bengtsson, M.M.; Romani, A.M.; Packmann, A.I. The ecology and biogeochemistry of stream biofilms. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2016, 14, 251–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azam, F.; Malfatti, F. Microbial structuring of marine ecosystems. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2007, 5, 782–791, Erratum in Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2007, 5, 966. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costerton, J.W.; Stewart, P.S.; Greenberg, E.P. Bacterial biofilms: A common cause of persistent infections. Science 1999, 284, 1318–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flemming, H.C. The perfect slime. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2011, 86, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beitelshees, M.; Hill, A.; Jones, C.H.; Pfeifer, B.A. Phenotypic Variation during Biofilm Formation: Implications for Anti-Biofilm Therapeutic Design. Materials 2018, 11, 1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, R.; Santhakumari, S.; Poonguzhali, P.; Geetha, M.; Dyavaiah, M.; Lin, X. Bacterial Biofilm Inhibition: A Focused Review on Recent Therapeutic Strategies for Combating the Biofilm Mediated Infections. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 676458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortega-Pena, S.; Hernandez-Zamora, E. Microbial biofilms and their impact on medical areas: Physiopathology, diagnosis and treatment. Bol. Med. Hosp. Infant. Mex. 2018, 75, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, D. Understanding biofilm resistance to antibacterial agents. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2003, 2, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dostert, M.; Trimble, M.J.; Hancock, R.E.W. Antibiofilm peptides: Overcoming biofilm-related treatment failure. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 2718–2728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, S.; Mohler, J.; Mahajan, S.D.; Schwartz, S.A.; Bruggemann, L.; Aalinkeel, R. Microbial Biofilm: A Review on Formation, Infection, Antibiotic Resistance, Control Measures, and Innovative Treatment. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1614, Correction in Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1961. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms12101961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thewes, N.; Loskill, P.; Jung, P.; Peisker, H.; Bischoff, M.; Herrmann, M.; Jacobs, K. Hydrophobic interaction governs unspecific adhesion of staphylococci: A single cell force spectroscopy study. Beilstein J. Nanotechnol. 2014, 5, 1501–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Tian, Y.; Hu, Z.; Wang, C.; Xie, P.; Chen, L.; Yang, F.; Liang, Y.; Mu, C.; Wei, C.; et al. Bis-(3′-5′)-cyclic dimeric guanosine monophosphate (c-di-GMP) mediated membrane fouling in membrane bioreactor. J. Membr. Sci. 2022, 646, 120224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, K.A.; Dodson, K.W.; Caparon, M.G.; Hultgren, S.J. A tale of two pili: Assembly and function of pili in bacteria. Trends Microbiol. 2010, 18, 224–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, L.; Forest, K.T.; Maier, B. Type IV pili: Dynamics, biophysics and functional consequences. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2019, 17, 429–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, T.J.; Geoghegan, J.A.; Ganesh, V.K.; Höök, M. Adhesion, invasion and evasion: The many functions of the surface proteins of Staphylococcus aureus. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2014, 12, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, I.R.; Owen, P.; Nataro, J.P. Molecular switches—The ON and OFF of bacterial phase variation. Mol. Microbiol. 1999, 33, 919–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tielker, D.; Hacker, S.; Loris, R.; Strathmann, M.; Wingender, J.; Wilhelm, S.; Rosenau, F.; Jaeger, K.E. Pseudomonas aeruginosa lectin LecB is located in the outer membrane and is involved in biofilm formation. Microbiology 2005, 151 Pt 5, 1313–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zemke, A.C.; D’Amico, E.J.; Torres, A.M.; CarreñoFlórez, G.P.; Keeley, P.; DuPont, M.; Kasturiarachi, N.; Bomberger, J.M. Bacterial respiratory inhibition triggers dispersal of Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2023, 89, e0110123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulwahhab, A.; Al Marjani, M.; Abdulghany, Z. Biofilm formation and persistence in antibioticresistant Escherichia coli: Nanoparticle strategies for managing conjugative resistance. Microbes Infect. Dis. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MuñozEgea, M.C.; GarcíaPedrazuela, M.; Mahillo, I.; Esteban, J. Effect of ciprofloxacin in the ultrastructure and development of biofilms formed by rapidly growing mycobacteria. BMC Microbiol. 2015, 15, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gopinathan, H.; Johny, T.K.; Bhat, S.G. Enhanced CAUTI Risk due to Strong Biofilm Forming MDR Bacteria in Indwelling Urinary Catheters. Austin. J. Microbiol. 2021, 6, 1030. [Google Scholar]

- Danin, P.E.; Girou, E.; Legrand, P.; Louis, B.; Fodil, R.; Christov, C.; Devaquet, J.; Isabey, D.; Brochard, L. Description and microbiology of endotracheal tube biofilm in mechanically ventilated subjects. Respir. Care 2015, 60, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsikogianni, M.; Missirlis, Y.F. Concise review of mechanisms of bacterial adhesion to biomaterials and of techniques used in estimating bacteria-material interactions. Eur. Cells Mater. 2004, 8, 37–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A.; Aggarwal, A.; Khan, F. Medical Device-Associated Infections Caused by Biofilm-Forming Microbial Pathogens and Controlling Strategies. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asensio, N.C.; Rendón, J.M.; González López, J.J.; Tizzano, S.G.; Martín Gómez, M.T.; Burgas, M.T. Time-resolved dual transcriptomics of Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm formation in cystic fibrosis. Biofilm 2025, 10, 100301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauten, A.; Martinović, M.; Kursawe, L.; Kikhney, J.; Affeld, K.; Kertzscher, U.; Falk, V.; Moter, A. Bacterial biofilms in infective endocarditis: An in vitro model to investigate emerging technologies of antimicrobial cardiovascular device coatings. Clin. Res. Cardiol. 2021, 110, 323–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamal, M.; Tasneem, U.; Hussain, T.; Andleeb, S. Bacterial Biofilm: Its Composition, Formation and Role in Human Infections. Res. Rev. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015, 4, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Rather, M.A.; Gupta, K.; Mandal, M. Microbial biofilm: Formation, architecture, antibiotic resistance, and control strategies. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2021, 52, 1701–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grari, O.; Ezrari, S.; El Yandouzi, I.; Benaissa, E.; Ben Lahlou, Y.; Lahmer, M.; Saddari, A.; Elouennass, M.; Maleb, A. A comprehensive review on biofilm-associated infections: Mechanisms, diagnostic challenges, and innovative therapeutic strategies. Microbe 2025, 8, 100436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.-M.C.; Wang, H.Z.; Høiby, N.; Song, Z.J. Strategies for combating bacterial biofilm infections. Int. J. Oral Sci. 2015, 7, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cangui-Panchi, S.P.; Nacato-Toapanta, A.L.; Enriquez-Martinez, L.J.; Salinas-Delgado, G.A.; Reyes, J.; Garzon-Chavez, D.; Machado, A. Battle royale: Immune response on biofilms—Host-pathogen interactions. Curr. Res. Immunol. 2023, 4, 100057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, J.F.; Hahn, M.M.; Gunn, J.S. Chronic biofilm-based infections: Skewing of the immune response. Pathog. Dis. 2018, 76, fty023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atri, C.; Guerfali, F.Z.; Laouini, D. Role of Human Macrophage Polarization in Inflammation during Infectious Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van, R.Z.; Kielian, T. Immune-based strategies for the treatment of biofilm infections. Biofilm 2025, 9, 100264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, V.F.L.; Soh, M.M.; Jaggi, T.K.; Mac Aogáin, M.; Chotirmall, S.H. The Microbial Endocrinology of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: Inflammatory and Immune Perspectives. Arch. Immunol. Ther. Exp. 2018, 66, 329–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plotkin, B.J.; Halkyard, S.; Spoolstra, E.; Micklo, A.; Kaminski, A.; Sigar, I.M.; Konaklieva, M.I. The Role of the Insulin/Glucose Ratio in the Regulation of Pathogen Biofilm Formation. Biology 2023, 12, 1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Luo, J.; Kong, J.; Ding, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wang, K. Insulin treatment enhances pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm formation by increasing intracellular cyclic di-GMP levels, leading to chronic wound infection and delayed wound healing. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2019, 11, 3261–3279, Correction in Am. J. Transl. Res. 2020, 12, 8259–8261. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, N.; Curtis, J.C.; Plotkin, B.J. Insulin Regulation of Escherichia coli Abiotic Biofilm Formation: Effect of Nutrients and Growth Conditions. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abed, W.G.; Al-Shawk, R.S.; Jassim, K.A. The Role of Insulin Level on the Biofilm-Forming Capacity in Diabetes-Related Urinary Tract Infection. Mustansiriya Med. J. 2021, 20, 66–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acierno, C.; Nevola, R.; Barletta, F.; Rinaldi, L.; Sasso, F.C.; Adinolfi, L.E.; Caturano, A. Multidrug-Resistant Infections and Metabolic Syndrome: An Overlooked Bidirectional Relationship. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzaei, R.; Sabokroo, N.; Ahmadyousefi, Y.; Motamedi, H.; Karampoor, S. Immunometabolism in biofilm infection: Lessons from cancer. Mol. Med. 2022, 28, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamil, M.A.; Peeran, S.W.; Basheer, S.N.; Elhassan, A.; Alam, M.N.; Thiruneervannan, M. Role of Resistin in Various Diseases with Special Emphasis on Periodontal and Periapical Inflammation—A Review. J. Pharm. Bioallied. Sci. 2023, 15, S31–S35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Checa-Ros, A.; Hsueh, W.C.; Merck, B.; González-Torres, H.; Bermúdez, V.; D’Marco, L. Obesity and Oral Health: The Link Between Adipokines and Periodontitis. TouchREV. Endocrinol. 2024, 20, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watters, C.; Everett, J.A.; Haley, C.; Clinton, A.; Rumbaugh, K.P. Insulin treatment modulates the host immune system to enhance Pseudomonas aeruginosa wound biofilms. Infect. Immun. 2014, 8, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahim, S.; Rahman, R.; Jhuma, T.A.; Ayub, M.; Khan, S.N.; Hossain, A.; Karim, M.M. Disrupting antimicrobial resistance: Unveiling the potential of vitamin C in combating biofilm formation in drug-resistant bacteria. BMC Microbiol. 2025, 25, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Suhaimi, E.A.; AlRubaish, A.A.; Aldossary, H.A.; Homeida, M.A.; Shehzad, A.; Homeida, A.M. Obesity and Cognitive Function: Leptin Role Through Blood-Brain Barrier and Hippocampus. Mol. Neurobiol. 2025, 62, 16280–16301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Bu, X.; Chen, D.; Wu, X.; Wu, H.; Caiyin, Q.; Qiao, J. Molecules-mediated bidirectional interactions between microbes and human cells. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes 2025, 11, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamada, N.; Chen, G.Y.; Inohara, N.; Núñez, G. Control of pathogens and pathobionts by the gut microbiota. Nat. Immunol. 2013, 14, 685–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nami, Y.; Shaghaghi Ranjbar, M.; Modarres Aval, M.; Haghshenas, B. Harnessing Lactobacillus-derived SCFAs for food and health: Pathways, genes, and functional implications. Curr. Res. Microb. Sci. 2025, 9, 100496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadiq, F.A.; Burmølle, M.; Heyndrickx, M.; Flint, S.; Lu, W.; Chen, W.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, H. Community-wide changes reflecting bacterial interspecific interactions in multispecies biofilms. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2021, 47, 338–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, A.; Sun, J.; Liu, Y. Understanding bacterial biofilms: From definition to treatment strategies. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1137947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agarwal, H.; Gurnani, B.; Pippal, B.; Jain, N. Capturing the micro-communities: Insights into biogenesis and architecture of bacterial biofilms. BBA Adv. 2024, 7, 100133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.Y.; Prentice, E.L.; Webber, M.A. Mechanisms of antimicrobial resistance in biofilms. npj Antimicrob. Resist. 2024, 2, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mace, M.A.; Krummenauer, M.E.; Lopes, W.; Vainstein, M.H. Medically Important Fungi in Multi-Species Biofilms: Microbial Interactions, Clinical Implications and Therapeutic Strategies. Curr. Trop. Med. Rep. 2024, 11, 224–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Chen, C.; Hu, J.; Liu, C.; Ning, Y.; Lu, F. Current strategies for monitoring and controlling bacterial biofilm formation on medical surfaces. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 282, 116709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omwenga, E.O.; Awuor, S.O. The Bacterial Biofilms: Formation, Impacts, and Possible Management Targets in the Healthcare System. Can J. Infect. Dis. Med. Microbiol. 2024, 2024, 1542576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong, G.J.; Khan, F.; Tabassum, N.; Cho, K.J.; Kim, Y.M. Strategies for controlling polymicrobial biofilms: A focus on antibiofilm agents. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2024, 64, 107243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaimat, A.N.; Ababneh, A.M.; Al-Holy, M.; Al-Nabulsi, A.; Osaili, T.; Abughoush, M.; Ayyash, M.; Holley, R.A. A review of bacterial biofilm components and formation, detection methods, and their prevention and control on food contact surfaces. Microbiol. Res. 2024, 15, 1973–1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turkina, M.V.; Vikström, E. Bacteria-Host Crosstalk: Sensing of the Quorum in the Context of Pseudomonas aeruginosa Infections. J. Innate Immun. 2019, 11, 263–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.T.; Lohia, G.K.; Chen, S.; Riquelme, S.A. Immunometabolic Regulation of Bacterial Infection, Biofilms, and Antibiotic Susceptibility. J. Innate Immun. 2024, 16, 143–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markowska, K.; Szymanek-Majchrzak, K.; Pituch, H.; Majewska, A. Understanding Quorum-Sensing and Biofilm Forming in Anaerobic Bacterial Communities. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 12808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haidari, H.; Vasilev, K. Novel Antibacterial Materials and Coatings—A Perspective by the Editors. Materials 2023, 16, 6302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elashnikov, R.; Ulbrich, P.; Vokata, B.; Pavlickova, V.S.; Svorcik, V.; Lyutakov, O.; Rimpelová, S. Physically Switchable Antimicrobial Surfaces and Coatings: General Concept and Recent Achievements. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 3083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.S.; Lim, M.C.; Kim, S.M.; Lee, J.Y. Extracellular matrix-degrading enzymes as a biofilm control strategy for food-related microorganisms. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2023, 32, 1745–1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.J.; Kim, J.S. Enhanced inactivation of Salmonella enterica Enteritidis biofilms on the stainless steel surface by proteinase K in the combination with chlorine. Food Control 2022, 132, 108519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, E.S.; Baek, S.Y.; Oh, T.; Koo, M.; Lee, J.Y.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, J.S. Strain variation in Bacillus cereus biofilms and their susceptibility to extracellular matrix-degrading enzymes. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0245708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Sorribas, A.; Poilvache, H.; Kamarudin, N.H.N.; Braem, A.; Van Bambeke, F. Hydrolytic Enzymes as Potentiators of Antimicrobials against an Inter-Kingdom Biofilm Model. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022, 10, e0258921, Correction in Microbiol. Spectr. 2022, 11, e0467122. https://doi.org/10.1128/spectrum.04671-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Liu, C.; Feng, J.; Yang, A.; Guo, F.; Qiao, J. QSIdb: Quorum sensing interference molecules. Brief Bioinform. 2021, 22, bbaa218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McInnis, C.E.; Blackwell, H.E. Non-native N-aroyl L-homoserine lactones are potent modulators of the quorum sensing receptor RpaR in Rhodopseudomonas palustris. Chembiochem 2014, 15, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.H.; Dong, Y.H. Quorum sensing and signal interference: Diverse implications. Mol. Microbiol. 2004, 53, 1563–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, L.; Shi, W.; Hao, X.; Luan, L.; Wang, S.; Lu, J.; Zhang, Q. Synergistic Photodynamic/Antibiotic Therapy with Photosensitive MOF-Based Nanoparticles to Eradicate Bacterial Biofilms. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lluberas, G.; Batista-Menezes, D.; Zuñiga-Umaña, J.M.; Montes de Oca-Vásquez, G.; Lecot, N.; Vega-Baudrit, J.R.; Lopretti, M. Biofilms Functionalized Based on Bioactives and Nanoparticles with Fungistatic and Bacteriostatic Properties for Food Packing Uses. Biol. Life Sci. Forum. 2023, 28, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Sheng, Y.; Chen, Z.; Wu, W.; Lu, Y. Engineered organic nanoparticles to combat biofilms. Discov. Today 2023, 28, 103455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldossary, H.A.; Rehman, S.; Jermy, B.R.; AlJindan, R.; Aldayel, A.; AbdulAzeez, S.; Akhtar, S.; Khan, F.A.; Borgio, J.F.; Al-Suhaimi, E.A. Therapeutic Intervention for Various Hospital Setting Strains of Biofilm Forming Candida auris with Multiple Drug Resistance Mutations Using Nanomaterial Ag-Silicalite-1 Zeolite. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 2251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakeeha, G.; AlHarbi, S.; Auda, S.; Balto, H. The Impact of Silver Nanoparticles’ Size on Biofilm Eradication. Int. Dent. J. 2025, 75, 1213–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amankwah, S.; Abdella, K.; Kassa, T. Bacterial Biofilm Destruction: A Focused Review on The Recent Use of Phage-Based Strategies with Other Antibiofilm Agents. Nanotechnol. Sci. Appl. 2021, 14, 161–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palma, M.; Qi, B. Advancing Phage Therapy: A Comprehensive Review of the Safety, Efficacy, and Future Prospects for the Targeted Treatment of Bacterial Infections. Infect. Dis. Rep. 2024, 16, 1127–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memariani, M.; Memariani, H. Anti-Biofilm Effects of Melittin: Lessons Learned and the Path Ahead. Int. J. Pep. Res. Ther. 2024, 30, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridyard, K.E.; Overhage, J. The Potential of Human Peptide LL-37 as an Antimicrobial and Anti-Biofilm Agent. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.; Lyu, Y.; Cui, X.; Zhang, C.; Meng, Q. How antimicrobial peptide indolicidin and its derivatives interact with phospholipid membranes: Molecular dynamics simulation. J. Mol. Struct. 2024, 1312, 138625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desrousseaux, C.; Sautou, V.; Descamps, S.; Traore, O. Modification of the surfaces of medical devices to prevent microbial adhesion and biofilm formation. J. Hosp. Infect. 2013, 85, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sundriyal, P.; Sahu, M.; Prakash, O.; Bhattacharya, S. Long-term surface modification of PEEK polymer using plasma and PEG silane treatment. Surf. Interfaces 2021, 25, 101253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, T.; Attarilar, S.; Liu, S.; Liu, J.; Song, X.; Li, L.; Zhao, B.; Tang, Y. Surface Modification Techniques of Titanium and its Alloys to Functionally Optimize Their Biomedical Properties: Thematic Review. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8, 603072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barzegari, A.; Kheyrolahzadeh, K.; Hosseiniyan Khatibi, S.M.; Sharifi, S.; Memar, M.Y.; Zununi Vahed, S. The Battle of Probiotics and Their Derivatives Against Biofilms. Infect. Drug Resist. 2020, 13, 659–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, S.; Sharma, P.; Kalia, N.; Singh, J.; Kaur, S. Anti-biofilm Properties of the Fecal Probiotic Lactobacilli Against Vibrio spp. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2018, 8, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salas-Jara, M.J.; Ilabaca, A.; Vega, M.; Garcia, A. Biofilm Forming Lactobacillus: New Challenges for the Development of Probiotics. Microorganisms 2016, 4, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, N.B.S.; Marques, L.A.; Röder, D.D.B. Diagnosis of biofilm infections: Current methods used, challenges and perspectives for the future. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2021, 131, 2148–2160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, T.; Liu, Z.; Wang, H.; Zhang, H.; Li, H.; Lu, W.; Zhu, J. Multi-omics analysis reveals genes and metabolites involved in Bifidobacterium pseudocatenulatum biofilm formation. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1287680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hernández-Huerta, M.T.; Pérez-Campos, E.; Pérez-Campos Mayoral, L.; Vásquez Martínez, I.P.; Reyna González, W.; Jarquín González, E.E.; Aldossary, H.; Alhabib, I.; Yamani, L.Z.; Elhadi, N.; et al. Proactive Strategies to Prevent Biofilm-Associated Infections: From Mechanistic Insights to Clinical Translation. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 2726. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122726

Hernández-Huerta MT, Pérez-Campos E, Pérez-Campos Mayoral L, Vásquez Martínez IP, Reyna González W, Jarquín González EE, Aldossary H, Alhabib I, Yamani LZ, Elhadi N, et al. Proactive Strategies to Prevent Biofilm-Associated Infections: From Mechanistic Insights to Clinical Translation. Microorganisms. 2025; 13(12):2726. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122726

Chicago/Turabian StyleHernández-Huerta, María Teresa, Eduardo Pérez-Campos, Laura Pérez-Campos Mayoral, Itzel Patricia Vásquez Martínez, Wendy Reyna González, Efrén Emmanuel Jarquín González, Hanan Aldossary, Ibrahim Alhabib, Lamya Zohair Yamani, Nasreldin Elhadi, and et al. 2025. "Proactive Strategies to Prevent Biofilm-Associated Infections: From Mechanistic Insights to Clinical Translation" Microorganisms 13, no. 12: 2726. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122726

APA StyleHernández-Huerta, M. T., Pérez-Campos, E., Pérez-Campos Mayoral, L., Vásquez Martínez, I. P., Reyna González, W., Jarquín González, E. E., Aldossary, H., Alhabib, I., Yamani, L. Z., Elhadi, N., Al-Suhaimi, E., & Cabrera-Fuentes, H. A. (2025). Proactive Strategies to Prevent Biofilm-Associated Infections: From Mechanistic Insights to Clinical Translation. Microorganisms, 13(12), 2726. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122726