Comparing the Effectiveness of UV-C on Dynamically Formed Field Biofilms

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

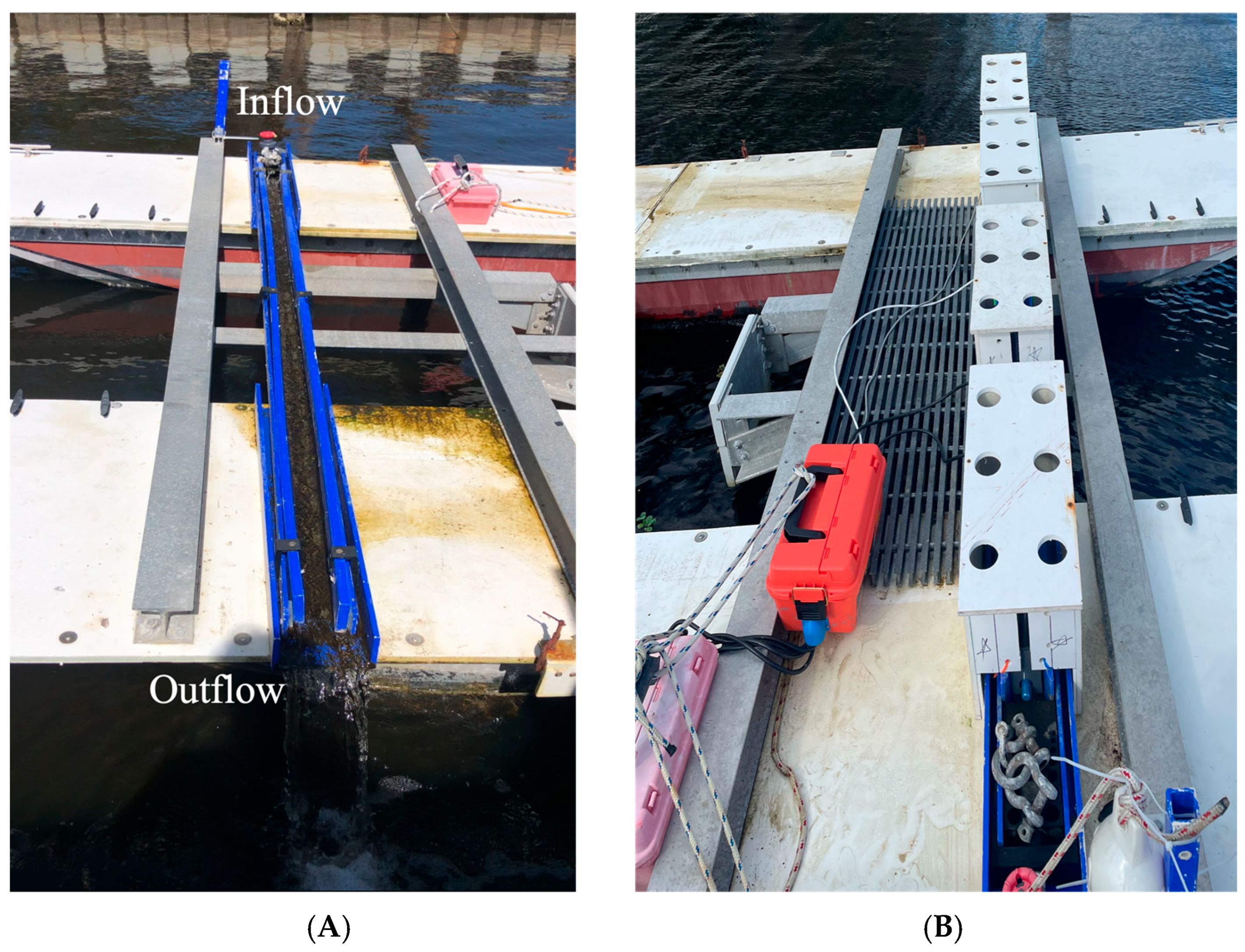

2.1. Biofilm Development

2.2. UV-C Exposure

2.3. Biofilm Characterization

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

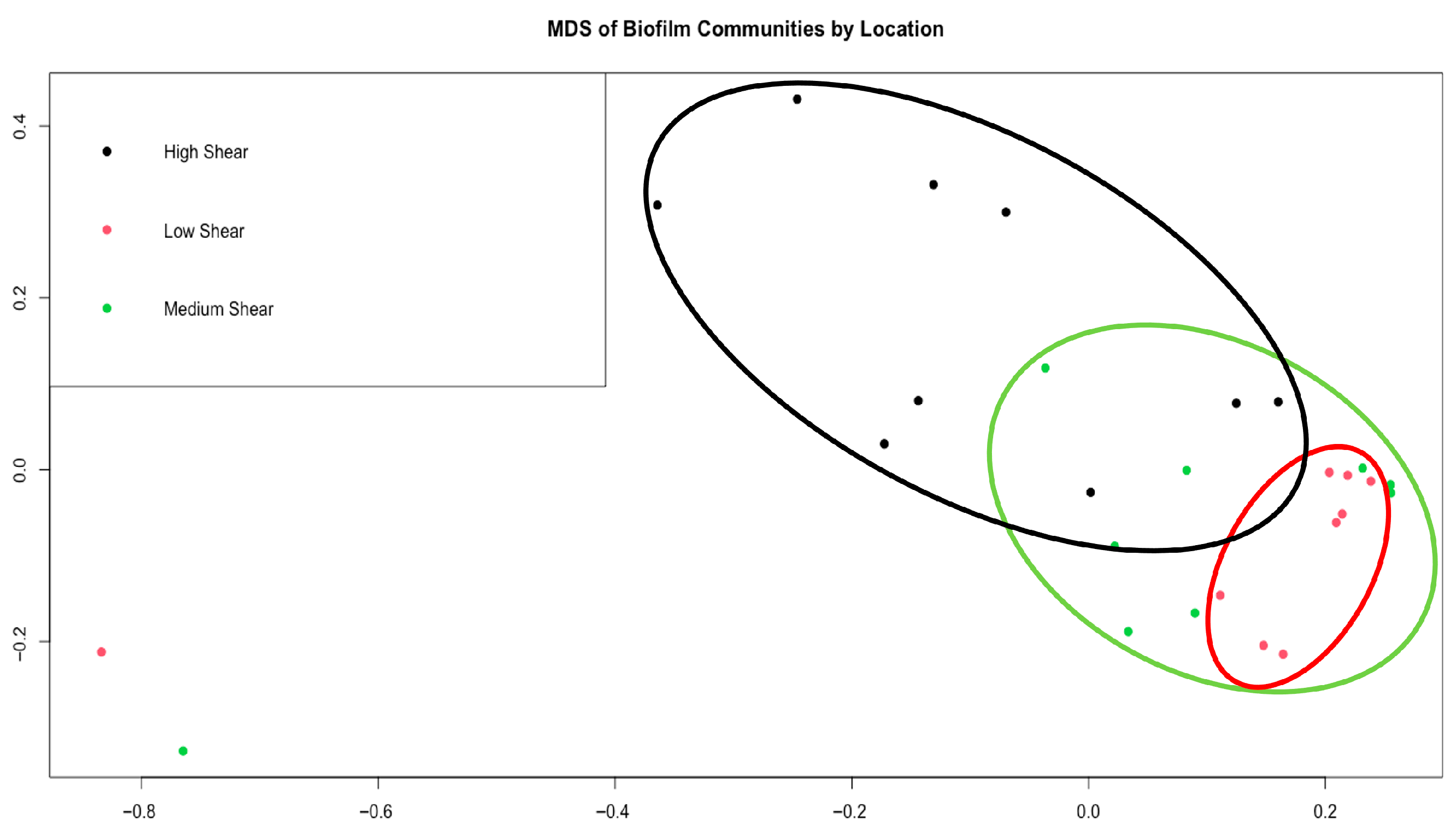

3.1. Pre-UV-C Biofilm Composition

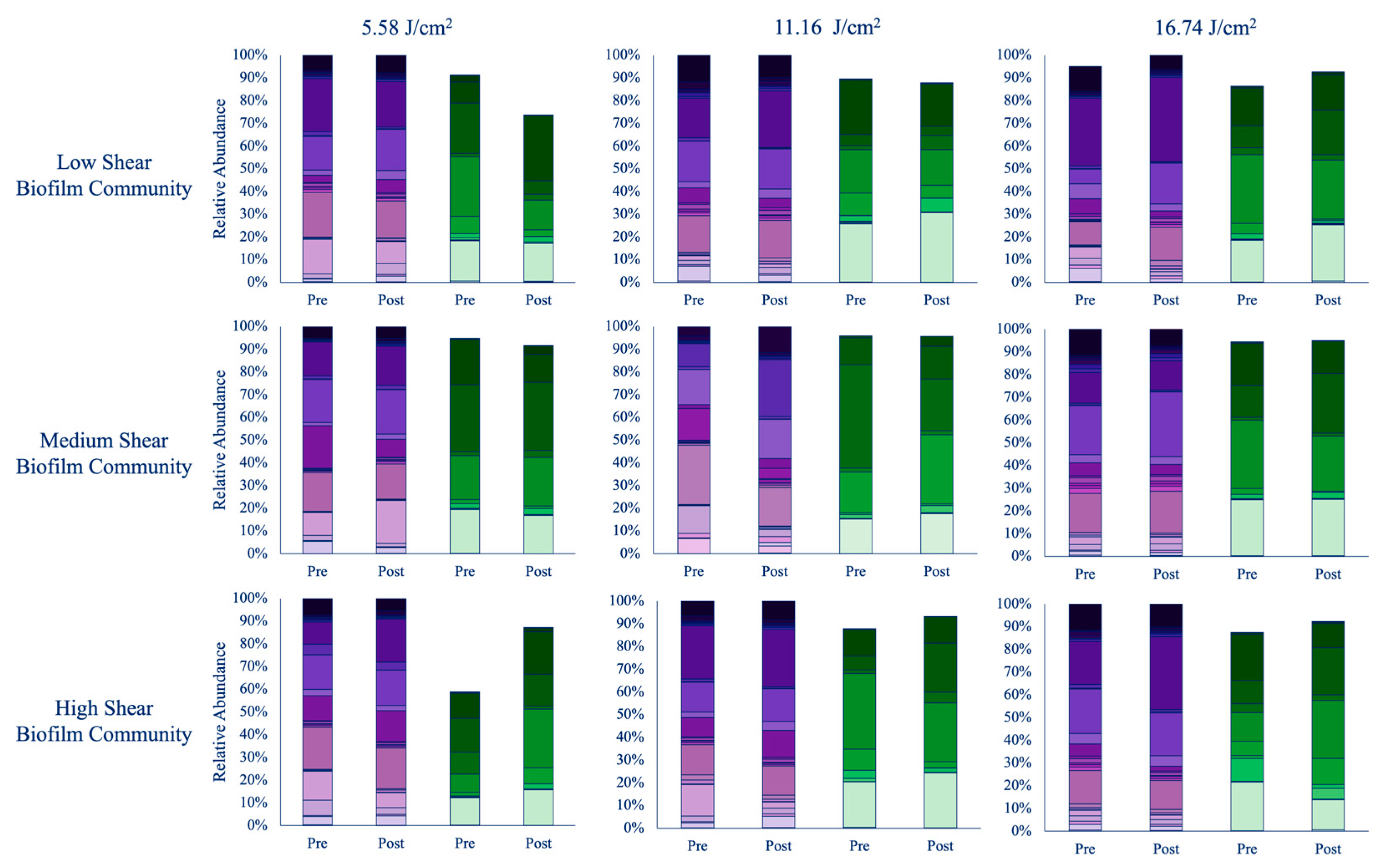

3.1.1. 30 min (5.58 J/cm2)

3.1.2. 60 min (11.16 J/cm2)

3.1.3. 90 min (16.74 J/cm2)

3.2. Post UV-C Dosing Biofilm Composition

3.2.1. 30 min (5.58 J/cm2)

3.2.2. 60 min (11.16 J/cm2)

3.2.3. 90 min (16.74 J/cm2)

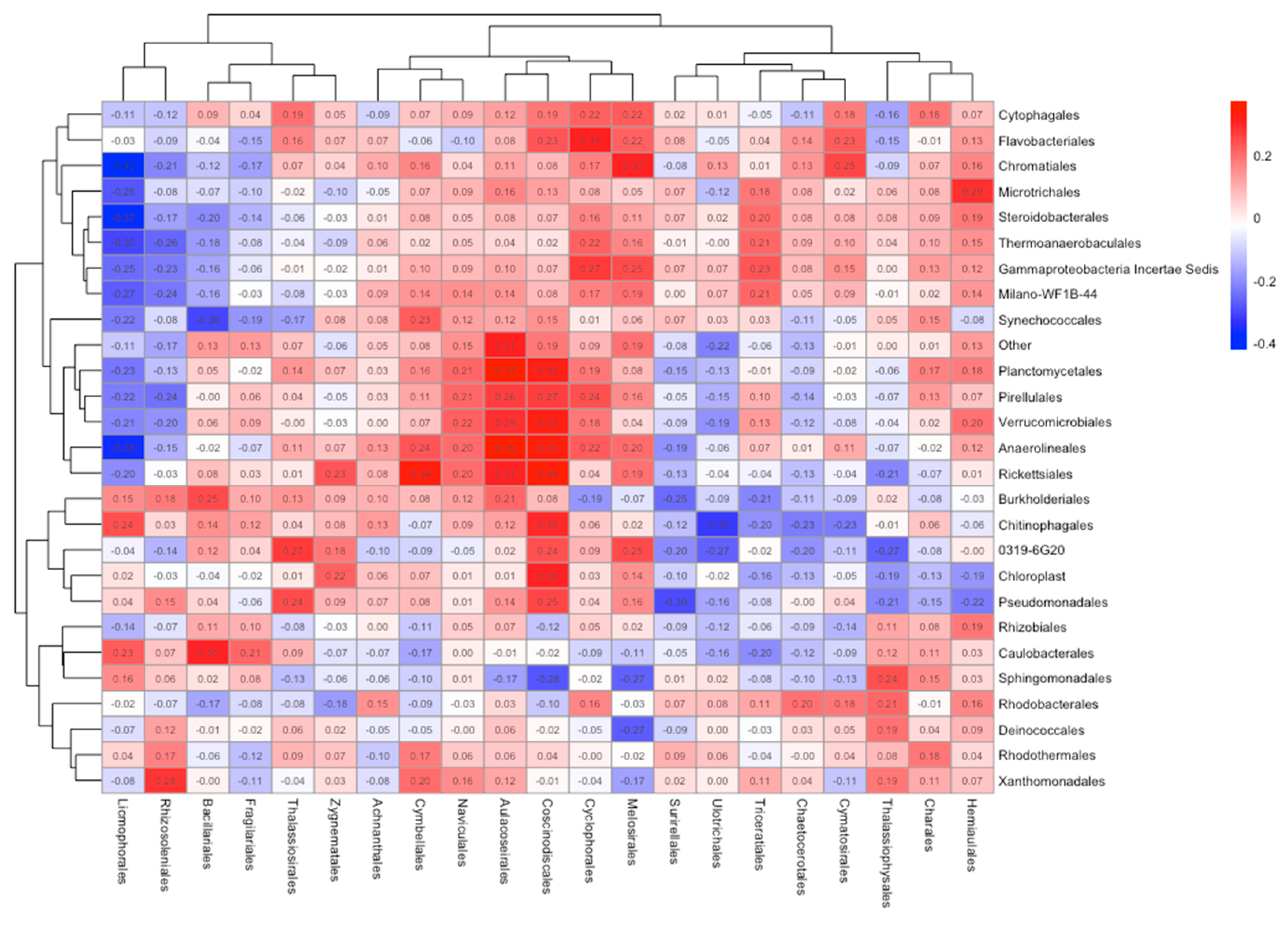

3.3. Bacteria and Diatom Correlation

4. Discussion

4.1. UV-C Effects on Biomass

4.2. UV-C Effects on Biofilm Community

4.3. Considerations for Future Research

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lindholdt, A.; Dam-Johansen, K.; Olsen, S.M.; Yebra, D.M.; Kiil, S. Effects of biofouling development on drag forces of hull coatings for ocean-going ships: A review. J. Coat. Technol. Res. 2015, 12, 415–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, M.P.; Swain, G.W. The influence of biofilms on skin friction drag. Biofouling 2000, 15, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, C.S.; Wier, T.P.; First, M.R.; Grant, J.F.; Riley, S.C.; Robbins-Wamsley, S.H.; Tamburri, M.N.; Ruiz, G.M.; Miller, A.W.; Drake, L.A. Quantifying the extent of niche areas in the global fleet of commercial ships: The potential for “super-hot spots” of biofouling. Biol. Invasions 2017, 19, 1745–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, I.; Cahill, P.; Hinz, A.; Kluza, D.; Scianni, C.; Georgiades, E. A review of biofouling of ships’ internal seawater systems. Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 8, 761531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobretsov, S.; Rittschof, D. Love at first taste: Induction of larval settlement by marine microbes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braga, C.R.; Richard, K.N.; Gardner, H.; Swain, G.; Hunsucker, K.Z. Investigating the impacts of UVC radiation on natural and cultured biofilms: An assessment of cell viability. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoeher, P.A.; Zenk, O.; Cisewski, B.; Boos, K.; Groeger, J. UVC-based biofouling suppression for long-term deployment of underwater cameras. IEEE J. Ocean. Eng. 2023, 48, 1389–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitworth, P.; Aldred, N.; Reynolds, K.J.; Plummer, J.; Duke, P.W.; Clare, A.S. Importance of duration, duty-cycling and thresholds for the implementation of ultraviolet C in marine biofouling control. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 8, 809011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard, K.N.; Palmer, A.; Swain, G.; Hunsucker, K.Z. Assessing the impact of UV-C exposure on pre-existing cultured marine diatom biofilms. Biofilm 2025, 9, 100285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfendler, S.; Alaoui-Sossé, B.; Alaoui-Sossé, L.; Bousta, F.; Aleya, L. Effects of UV-C radiation on Chlorella vulgaris, a biofilm-forming alga. J. Appl. Phycol. 2018, 30, 1607–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard, K.N.; Hunsucker, K.Z.; Gardner, H.; Hickman, K.; Swain, G. The application of UVC used in synergy with surface material to prevent marine biofouling. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2021, 9, 662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purvis, K.; Curnew, K.H.; Trevors, A.L.; Hunter, A.T.; Wilson, E.R.; Wyeth, R.C. Single Ultraviolet-C light treatment of early stage marine biofouling delays subsequent community development. Biofouling 2022, 38, 536–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braga, C.; Hunsucker, K.; Gardner, H.; Swain, G. A novel design to investigate the impacts of UV exposure on marine biofouling. Appl. Ocean Res. 2020, 101, 102226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zargiel, K.A.; Swain, G.W. Static vs dynamic settlement and adhesion of diatoms to ship hull coatings. Biofouling 2014, 30, 115–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McIntire, C.D. Some effects of current velocity on periphyton communities in laboratory streams. Hydrobiologia 1966, 27, 559–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisen, W.K.; Spencer, D.J. Succession and current demand relationships of diatoms on artificial substrates in prater’s creek, south carolina 1, 2. J. Phycol. 1970, 6, 117–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitford, L.A. The current effect and growth of fresh-water algae. Trans. Am. Microsc. Soc. 1960, 79, 302–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinaman, A.D.; McIntire, C.D. Effects of Current Velocity and Light Energy on the Structure of Periphyton Assemblage in Laboratory Streams 1. J. Phycol. 1986, 22, 352–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, R.; Glover, R. Effects of algal density and current on ion transport through periphyton communities. Limnol. Oceanogr. 1993, 38, 1276–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomason, J.C.; Letissier, M.D.A.A.; Thomason, P.O.; Field, S.N. Optimising settlement tiles: The effects of surface texture and energy, orientation and deployment duration upon the fouling community. Biofouling 2002, 18, 293–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunsucker, K.Z.; Koka, A.; Lund, G.; Swain, G. Diatom community structure on in-service cruise ship hulls. Biofouling 2014, 30, 1133–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitworth, P.; Clare, A.S.; Finlay, J.A.; Piola, R.F.; Plummer, J.; Aldred, N. Long-term ultraviolet treatment for macrofouling control in northern and southern hemispheres. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 2211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, S.A.; Parker, M.S.; Armbrust, E.V. Interactions between diatoms and bacteria. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2012, 76, 667–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leary, D.H.; Li, R.W.; Hamdan, L.J.; Hervey IV, W.J.; Lebedev, N.; Wang, Z.; Vora, G.J. Integrated metagenomic and metaproteomic analyses of marine biofilm communities. Biofouling 2014, 30, 1211–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunsucker, K.Z.; Gardner, H.; Lieberman, K.; Swain, G. Using hydrodynamic testing to assess the performance of fouling control coatings. Ocean Eng. 2019, 194, 106677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowan, K.S. Photosynthetic Pigments of Algae; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz, O.N.; Brown, L.M.; Striebich, R.C.; Smart, C.E.; Bowen, L.L.; Lee, J.S.; Gunasekera, T.S. Effect of conventional and alternative fuels on a marine bacterial community and the significance to bioremediation. Energy Fuels 2016, 30, 434–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson, D.A.; Karsch-Mizrachi, I.; Lipman, D.J.; Ostell, J.; Wheeler, D.L. GenBank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005, 33 (Suppl. S1), D34–D38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simis, S.G.; Huot, Y.; Babin, M.; Seppälä, J.; Metsamaa, L. Optimization of variable fluorescence measurements of phytoplankton communities with cyanobacteria. Photosynth. Res. 2012, 112, 13–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oguma, K.; Kita, R.; Sakai, H.; Murakami, M.; Takizawa, S. Application of UV light emitting diodes to batch and flow-through water disinfection systems. Desalination 2013, 328, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torkzadeh, H.; Cates, E.L. Biofilm growth under continuous UVC irradiation: Quantitative effects of growth conditions and growth time on intensity response parameters. Water Res. 2021, 206, 117747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabó, C.; Ohshima, H. DNA damage induced by peroxynitrite: Subsequent biological effects. Nitric Oxide 1997, 1, 373–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolton, J.R.; Linden, K.G. Standardization of methods for fluence (UV dose) determination in bench-scale UV experiments. J. Environ. Eng. 2003, 129, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kheyrandish, A.; Taghipour, F.; Mohseni, M. UV-LED radiation modeling and its applications in UV dose determination for water treatment. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2018, 352, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, B.G.; Cosgrove, E.G. The disinfection of sewage treatment plant effluents using ultraviolet light. Can. J. Chem. Eng. 1975, 53, 170–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollu, K.; Örmeci, B. Effect of particles and bioflocculation on ultraviolet disinfection of Escherichia coli. Water Res. 2012, 46, 750–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Pichel, F.; Bebout, B.M. Penetration of ultraviolet radiation into shallow water sediments: High exposure for photosynthetic communities. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 1996, 131, 257–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, G.; Riegl, B.M.; Foster, K.A.; Morris, L.J. Acoustic detection and mapping of muck deposits in the Indian River Lagoon, Florida. J. Coast. Res. 2018, 34, 856–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, M.P. Effects of coating roughness and biofouling on ship resistance and powering. Biofouling 2007, 23, 331–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schäfer, H.; Abbas, B.; Witte, H.; Muyzer, G. Genetic diversity of ‘satellite’bacteria present in cultures of marine diatoms. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2002, 42, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Grossart, H.P.; Levold, F.; Allgaier, M.; Simon, M.; Brinkhoff, T. Marine diatom species harbour distinct bacterial communities. Environ. Microbiol. 2005, 7, 860–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapp, M.; Schwaderer, A.S.; Wiltshire, K.H.; Hoppe, H.G.; Gerdts, G.; Wichels, A. Species-specific bacterial communities in the phycosphere of microalgae? Microb. Ecol. 2007, 53, 683–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wulff, A.; Roleda, M.Y.; Zacher, K.; Wiencke, C. Exposure to sudden light burst after prolonged darkness—A case study on benthic diatoms in Antarctica. Diatom Res. 2008, 23, 519–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Exposure Duration | Location | Shear Stress | Average Density | Average Biofilm Thickness (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30 min | Front | High | 4.17 × 105 ± 9.78 × 104 | 0.00 ± 0.00 |

| Middle | Medium | 1.69 × 106 ± 7.18 × 104 | 21.1 ± 33.7 | |

| Back | Low | 2.37 × 106 ± 3.47 × 105 | 72.0 ± 19.1 | |

| 60 min | Front | High | 4.00 × 105 ± 2.15 × 105 | 0.00 ± 0.00 |

| Middle | Medium | 1.75 × 106 ± 3.68 × 105 | 4.17 ± 10.2 | |

| Back | Low | 4.52 × 106 ± 8.40 × 105 | 17.0 ± 21.0 | |

| 90 min | Front | High | 2.24 × 106 ± 5.67 × 105 | 5.67 ± 17.0 |

| Middle | Medium | 5.83 × 106 ± 1.44 × 106 | 76.3 ± 22.8 | |

| Back | Low | 5.83 × 106 ± 1.76 × 106 | 84.6 ± 13.3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Richard, K.N.; Hunsucker, K.Z.; Swain, G.; Kardish, M.R. Comparing the Effectiveness of UV-C on Dynamically Formed Field Biofilms. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 2561. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13112561

Richard KN, Hunsucker KZ, Swain G, Kardish MR. Comparing the Effectiveness of UV-C on Dynamically Formed Field Biofilms. Microorganisms. 2025; 13(11):2561. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13112561

Chicago/Turabian StyleRichard, Kailey N., Kelli Z. Hunsucker, Geoffrey Swain, and Melissa R. Kardish. 2025. "Comparing the Effectiveness of UV-C on Dynamically Formed Field Biofilms" Microorganisms 13, no. 11: 2561. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13112561

APA StyleRichard, K. N., Hunsucker, K. Z., Swain, G., & Kardish, M. R. (2025). Comparing the Effectiveness of UV-C on Dynamically Formed Field Biofilms. Microorganisms, 13(11), 2561. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13112561