Elimination of Airborne Microorganisms Using Compressive Heating Air Sterilization Technology (CHAST): Laboratory and Nursing Home Setting

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

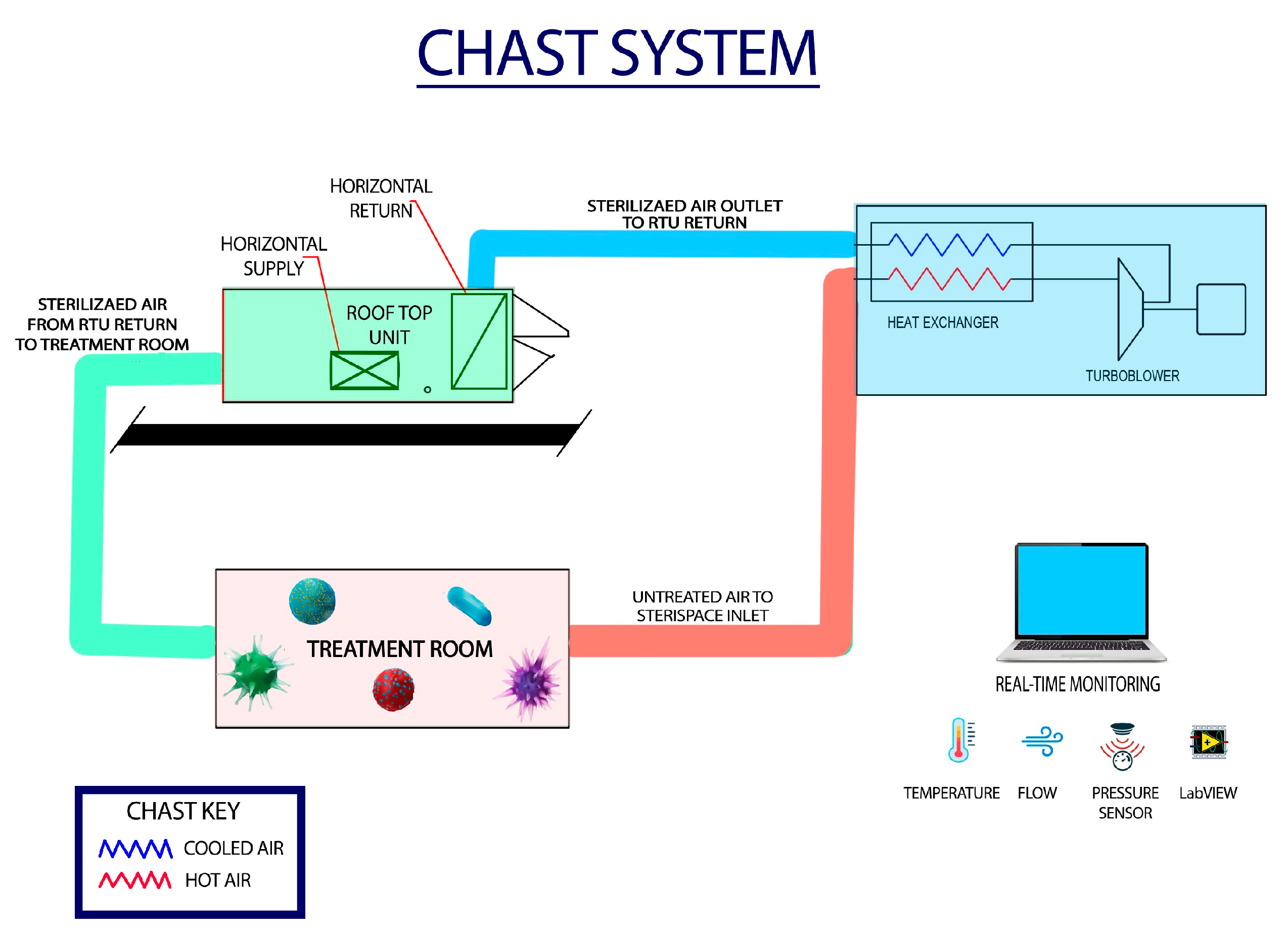

2.1. Compressive Heating Air Sterilization Technology (CHAST) System Description

2.2. Evaluation of CHAST Efficacy Under Controlled Laboratory Conditions

2.3. Evaluation of CHAST Efficacy in a Feasibility and Performance Validation of Air Sterilization Study in a Nursing Home Setting

2.4. Data Analysis and Statistical Methods

3. Results

3.1. Evaluating the Efficacy of CHAST Under Controlled Laboratory Conditions

- (i).

- CHAST Technology Delivers High-Efficacy Sterilization Across Designs and Scales: Multiple CHAST prototypes, tested under a range of flow rates and thermal conditions, consistently demonstrated robust microbial inactivation (Table 1). Across initial and advanced designs, including University at Buffalo laboratory units, DoD developmental prototypes, and scaled SBIR systems, all devices achieved at least 99.9% kill efficacy (≥3-log reduction), with the majority yielding > 6-log (99.9999%) reduction against representative bacterial spores, vegetative bacteria, and viruses such as MS2 bacteriophage. Notably, the technology-maintained performance across increasing scales (up to 5000 CFM systems) and against diverse challenge organisms, confirming that thermal compressive sterilization is reproducible, scalable, and independent of prototype configuration. Detailed results of each CHAST prototype, analysis site and results obtained are given as Table 1 in Supplemental Document.

- (ii).

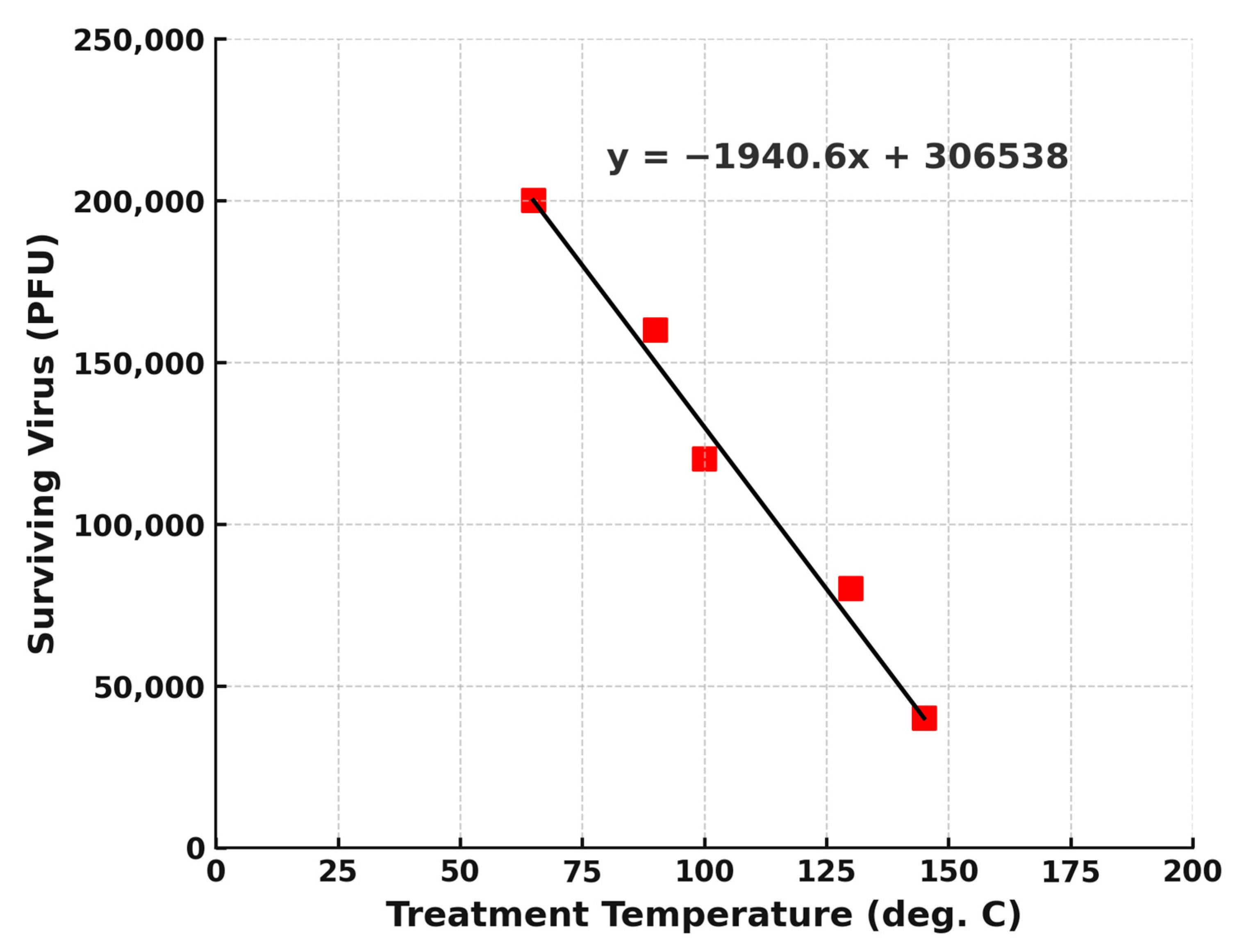

- Viral Elimination Studies and determination of optimum temperature for its elimination using CHAST: CHAST demonstrated complete inactivation of MS2 bacteriophage at a treatment temperature of 240 °C, consistent with its previously established efficacy against resilient bacterial spores and vegetative organisms. To further characterize the system’s capability for viral inactivation at lower thermal thresholds, a series of experiments was conducted using MS2 bacteriophage (1 × 107 PFU/mL) as a surrogate virus. The virus-laden aerosol was subjected to treatment at progressively reduced temperatures of 143 °C, 103 °C, 91 °C, and 64.5 °C, while maintaining consistent flow parameters. As depicted in Figure 2, viral survivability decreased markedly with increasing temperature, demonstrating a strong inverse correlation between treatment temperature and viable virus count. Although complete inactivation was not directly observed at the tested lower temperatures, extrapolation of the viral decay curve suggests that full viral inactivation likely occurs at approximately 170 °C. These findings underscore the flexibility of the CHAST system to operate effectively across a range of thermal conditions. When combined with appropriate residence times, achievable through flow rates in the 150–200 CFM range, the system can produce substantial viral reduction even at moderate temperatures. Furthermore, results indicate the potential for successful viral neutralization at even lower thermal thresholds, provided sufficient exposure time is achieved within the treatment zone.

3.2. Evaluation of Feasibility and Performance Validation of Air Sterilization of CHAST Efficacy in a Nursing Home Setting

- (i)

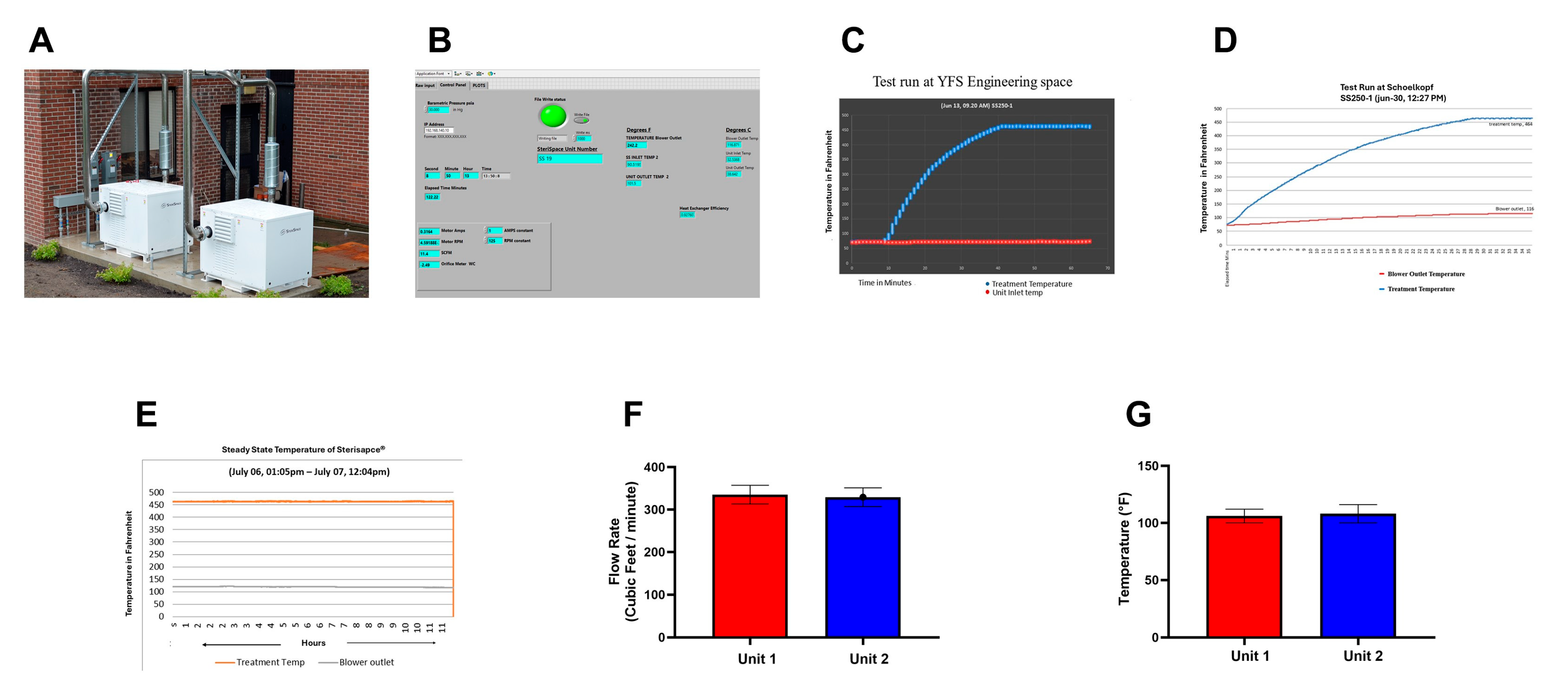

- CHAST Installation and machine performance summary: As shown in Figure 3A, two CHAST units (SS250-1 and SS250-2) were deployed, each configured with dedicated inlet and outlet ducts connected to the test room. The room itself was outfitted with two corresponding inlet vents and two outlet vents to ensure uniform and efficient sterilization of the enclosed space. Figure 3B illustrates the LabVIEW interface (Version 2023 Q3(64-bit) 23.30 f0), which enables real-time remote monitoring of key operational parameters. The LabVIEW software is integrated with the system to continuously capture and log data directly into Microsoft Excel, facilitating streamlined data collection and analysis. Monitored parameters included treatment temperature, air velocity at the outlet, and critical engineering metrics such as power consumption and current stability. Analysis of these data confirmed that the CHAST units operated with optimal motor RPM, efficiency, pressure, temperature, and airflow under field conditions, outperforming previous benchmarks and demonstrating exceptional real-world functionality. As shown in Figure 3C, the units reliably reached the target treatment temperature of 464 °F (240 °C) within 30 min and maintained this temperature consistently throughout the operation period. Monitoring curves indicated sustained thermal stability until the system shutdown. These findings aligned with field performance data (Figure 3D), confirming consistent and reproducible operational reliability. Minor fluctuations of ±2 °F observed during treatment (Figure 3E) were well within acceptable limits, further underscoring the system’s ability to maintain a stable and effective sterilization environment under real-world conditions.

- (ii)

- The flow rate of Sterilized air into the monitoring room with CHAST® operational: During the study, a handheld flow meter was used to measure the mean flow rate of sterilized air delivered into the room through the CHAST ductwork. As shown in Figure 3E, six consecutive measurements were recorded for each unit. The results indicated that Unit 1 achieved a mean flow rate of 335 ± 22 CFM, while Unit 2 recorded 329 ± 26 CFM (p > 0.05, n = 6), demonstrating consistent airflow performance across both systems. These values exceeded expected operational benchmarks and confirmed that the CHAST units were functioning at peak efficiency. Importantly, the existing HVAC system did not interfere with the integrity of airflow from the CHAST units. This was confirmed by independent handheld measurements of the mean air temperature entering the room, which aligned closely with system targets (Figure 3F). The ductwork configuration, illustrated in Figure 3A, was specifically designed to accommodate the dual-unit setup. Each CHAST unit was equipped with its own inlet and outlet duct, while the room itself featured two intake and two outlet vents, ensuring symmetrical and efficient distribution of sterilized air. This improvised ductwork design effectively optimized airflow circulation, enhancing the overall sterilization efficacy and maintaining a clean, contaminant-free environment throughout the testing period.

- (iii)

- CHAST Installation and Testing for Biological Efficacy in Baseline and post Post-Sterilization Air Samples in the feasibility study in a Nursing Home: To evaluate the real-world performance of CHAST in a nursing home, and feasibility and operational efficacy study was conducted by comparing air samples collected before and after system deployment. Two sampling phases were executed: a baseline assessment prior to CHAST activation and a follow-up collection after 72 h of continuous operation. Airborne microbial sampling was performed using a single-stage Andersen Airborne Impaction Sampler, which captures viable microorganisms from the air. Samples were obtained from six distinct locations within the facility, targeting both bacterial and fungal spores (Table 2). All samples were carefully labeled, sealed, and transported under sterile conditions for laboratory incubation and processed as described in the methods section. Baseline air sampling confirmed a non-sterile indoor environment, with measurable levels of both bacterial and fungal contamination. The average airborne bacterial load was 35 colony-forming units per cubic meter (CFU/m3), while fungal and mold concentrations averaged 17 CFU/m3 (Table 2). The most prevalent fungal species detected was Cladosporium spp., a common indoor genus. Additional fungal isolates included Penicillium spp. and Trichophyton spp., both known to persist in indoor air under favorable conditions. Bacterial isolates primarily consisted of environmental and commensal species, with Bacillus spp., a spore-forming genus widely present in both soil and air, emerging as the dominant type. Other significant bacterial genera identified included Staphylococcus spp., Streptococcus spp., and Actinomycetes. Notably, Staphylococcus spp. is commonly associated with human skin and mucosal surfaces, underscoring the human-associated bioburden present in the facility’s ambient air prior to CHAST activation.

- (iv)

- Air Sample Analysis for Biological Agents post-air sterilization: Air samples collected directly at the discharge outlet (Location A), where sterilized air enters the test room, exhibited an NGP status following seven days of incubation, confirming near complete elimination of viable microorganisms at the point of release. However, additional samples taken approximately six inches below the outlet duct at the same location, as well as from the return duct (Location B), directing air back into the CHAST system, revealed low-level microbial presence. These samples registered 7 CFU/m3 and contained identifiable microbial species, including Bacillus spp. (bacteria) and Actinomycete spp. (fungi), as detailed in Table 3. These findings suggest that while CHAST achieves full sterilization of air at the discharge point, minimal recontamination may occur in the immediate vicinity of the outlet or within the air recirculation pathway. Such contamination is likely attributable to ambient environmental exposure or incidental contact with surrounding surfaces, underscoring the importance of maintaining cleanroom-level controls around air distribution infrastructure in critical applications.

- (v)

- Mold and Fungal Testing in Air Samples Collected. Air sampling conducted to evaluate fungal spore and mold concentrations revealed distinct differences across sampling locations. At the discharge outlet (Location A), where sterilized air enters the room, the average fungal spore concentration was measured at 7 CFU/m3. In contrast, samples collected six inches below the outlet and at the return inlet (Location B), where ambient room air is drawn back into the CHAST unit, showed significantly elevated concentrations of 28 CFU/m3 and 50 CFU/m3, respectively (Table 3). To validate the sterilization efficacy at the point of discharge, follow-up sampling was performed at Location A. These subsequent samples demonstrated a consistent NGP status, even after eight days of incubation, confirming the complete absence of viable fungal spores or mold in the treated air (Table 4). Comparative analysis of the datasets revealed a 93% reduction in fungal spore concentration, based on the average spore count in sterilized air entering the room (3.5 CFU/m3) versus untreated air returning to the CHAST system (50 CFU/m3) (Table 3 and Table 4). These results highlight a key additional benefit of CHAST technology and its robust capability to inactivate airborne fungal and mold spores. This reinforces the system’s value not only in eliminating bacterial and viral pathogens but also in enhancing indoor air quality by controlling fungal contaminants in enclosed environments.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Healthcare-Associated Infections Fact Sheet; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Vincent, J.L. Nosocomial infections in adult intensive-care units. Lancet 2003, 361, 2068–2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leape, L.L. Reporting of adverse events. N. Engl. J. Med. 2002, 347, 1633–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohn, L.T. Organizing and managing care in a changing health system. Health Serv. Res. 2000, 35, 37–52. [Google Scholar]

- Kohn, L. To err is human: An interview with the Institute of Medicine’s Linda Kohn. Jt. Comm. J. Qual. Improv. 2000, 26, 227–234. [Google Scholar]

- CDC. HAI and Antimicrobial Use Prevalence Surveys. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/healthcare-associated-infections/php/haic-eip/antibiotic-use.html (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Strausbaugh, L.J.; Joseph, C.L. The burden of infection in long-term care. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2000, 21, 674–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- See, I.; Jackson, K.A.; Hatfield, K.M.; Paul, P.; Li, R.; Nadle, J.; Petit, S.; Ray, S.M.; Harrison, L.H.; Jeffrey, L.; et al. Characteristics of nursing homes with high rates of invasive methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2025, 73, 849–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassone, M.; Mody, L. Colonization with Multi-Drug Resistant Organisms in Nursing Homes: Scope, Importance, and Management. Curr. Geriatr. Rep. 2015, 4, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, J.; Liu, X.; Liu, C.; Chen, Q. HEPA filters for airliner cabins: State of the art and future development. Indoor Air 2022, 32, e13103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratliff, K.M.; Oudejans, L.; Archer, J.; Calfee, W.; Gilberry, J.U.; Hook, D.A.; Schoppman, W.E.; Yaga, R.W.; Brooks, L.; Ryan, S. Large-scale evaluation of microorganism inactivation by bipolar ionization and photocatalytic devices. Build. Environ. 2023, 227, 109804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobek, E.; Elias, D.A. Bipolar ionization rapidly inactivates real-world, airborne concentrations of infective respiratory viruses. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0293504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, S.L.; Hernandez, M.; Fennelly, K.; Martyny, J.; Macher, J.; Kujundzic, E. Efficacy of Ultraviolet Irradiation in Controlling the Spread of Tuberculosis; NIOSH final report, Contract 200–97–2602; US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Cincinnati, OH, USA, 2002; NTIS publication PB2003-103816. [Google Scholar]

- Nikitin, N.; Petrova, E.; Trifonova, E.; Karpova, O. Influenza virus aerosols in the air and their infectiousness. Adv Virol. 2014, 2014, 859090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tellier, R. COVID-19: The case for aerosol transmission. Interface Focus 2022, 12, 20210072, Erratum in: Interface Focus 2022, 13, 20220060. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsfs.2022.0060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). Method 0800: Bioaerosol Sampling. NIOSH Manual of Analytical Methods (NMAM), 4th ed.; DHHS (NIOSH) Publication No. 94-113; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Cincinnati, OH, USA, 1998. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/docs/2003-154/pdfs/0800.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- ISO 16000-3; Indoor Air—Part 3: Determination of Formaldehyde and Other Carbonyl Compounds—Active Sampling Method. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011.

- ISO 16000-36; Indoor Air—Part 36: Standard Method for the Determination of Cultivable Microorganisms—Surface Sampling with Contact Plates and Swabs. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

- ASTM D7391-20; Standard Test Method for Categorization and Quantification of Airborne Microbial Populations by Flow Cytometry. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2020.

- Reddy, M.; Heidarinejad, M.; Stephens, B.; Rubinstein, I. Adequate indoor air quality in nursing homes: An unmet medical need. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 765, 144273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentayeb, M.; Norback, D.; Bednarek, M.; Bernard, A.; Cai, G.; Cerrai, S.; Eleftheriou, K.K.; Gratziou, C.; Holst, G.J.; Lavaud, F.; et al. Indoor air quality, ventilation and respiratory health in elderly residents living in nursing homes in Europe. Eur. Respir. J. 2015, 45, 1228–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loureiro, A.; Ferreira, A.; Barros, N. Systematic review of the literature on indoor air quality in healthcare units and its effects on health. BMC Public Health 2025, 25, 2398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leece, P.; Whelan, M.; Costa, A.P.; Daneman, N.; Johnstone, J.; McGeer, A.; Brown, K.A. Nursing home crowding and outbreak-associated respiratory infection in Ontario, Canada before the COVID-19 pandemic (2014-19): A retrospective cohort study. Lancet Healthy Longev 2023, 4, e107–e114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crnich, C.J. Reimagining Infection Control in U.S. Nursing Homes in the Era of COVID-19. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2022, 23, 1909–1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasmussen, P.U.; Uhrbrand, K.; Frederiksen, M.W.; Madsen, A.M. Work in nursing homes and occupational exposure to endotoxin and bacterial and fungal species. Ann. Work. Expo. Health 2023, 67, 831–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.W.; Ramakrishnan, M.A.; Raynor, P.C.; Goyal, S.M. Effects of humidity and other factors on the generation and sam-pling of a coronavirus aerosol. Aerobiologia 2007, 23, 239–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiwar, W.; King, M.F.; Shuweihdi, F.; Fletcher, L.A.; Dancer, S.J.; Noakes, C.J. What is the relationship between indoor air quality parameters and airborne microorganisms in hospital environments? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Indoor Air 2021, 31, 1308–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonadonna, L.; Briancesco, R.; Coccia, A.M.; Meloni, P.; Rosa, G.L.; Moscato, U. Microbial air quality in healthcare facilities: Waterborne and bioaerosol-associated infections. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montoya, A.; Mody, L. Common infections in nursing homes: A review of current issues and challenges. Aging Health 2011, 7, 889–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Qian, H.; Hang, J.; Chen, X.; Cheng, P.; Ling, H.; Wang, S.; Liang, P.; Li, J.; Xiao, S.; et al. Evidence for probable aerosol transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in a poorly ventilated restaurant. Build. Environ. 2021, 196, 107788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMichael, T.M.; Currie, D.W.; Clark, S.; Pogosjans, S.; Kay, M.; Schwartz, N.G.; Lewis, J.; Baer, A.; Kawakami, V.; Lukoff, M.D.; et al. Epidemiology of COVID-19 in a long-term care facility in King County, Washington. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 2005–2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strausbaugh, L.J.; Sukumar, S.R.; Joseph, C.L. Infectious disease outbreaks in nursing homes: An unappreciated hazard for frail elderly persons. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2003, 36, 870–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shorr, A.F.; Ilges, D.T.; Micek, S.T.; Kollef, M.H. The importance of viruses in ventilator-associated pneumonia. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2023, 44, 1137–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russell, A.D. Lethal effects of heat on bacterial physiology and structure. Sci. Prog. 2003, 86, 115–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, J.; Smelt, J.; Vischer, N.O.E.; de Vos, A.L.; Setlow, P.; Brul, S. Heat Activation and Inactivation of Bacterial Spores: Is There an Overlap? Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2022, 88, e0232421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalski, W. Hospital Airborne Infection Control, 1st ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, A.; Csonka, L.N.; Alam, M.A. Analyzing Thermal Stability of Cell Membrane of Salmonella Using Time-Multiplexed Impedance Sensing. Biophys. J. 2018, 114, 609–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kan, Z.; Kwan, M.P.; Wong, M.S.; Huang, J.; Liu, D. Identifying the space-time patterns of COVID-19 risk and their associations with different built environment features in Hong Kong. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 772, 145379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kovacs, E.J.; Boe, D.M.; Boule, L.A.; Curtis, B.J. Inflammaging and the Lung. Clin. Geriatr. Med. 2017, 33, 459–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuetz, P.; Wirz, Y.; Sager, R.; Christ-Crain, M.; Stolz, D.; Tamm, M.; Bouadma, L.; E Luyt, C.; Wolff, M.; Chastre, J.; et al. Procalcitonin to initiate or discontinue antibiotics in acute respiratory tract infections. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 10, CD007498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pecson, B.M.; Martin, L.V.; Kohn, T. Quantitative PCR for determining the infectivity of bacteriophage MS2 upon inactivation by heat, UV-B radiation, and singlet oxygen. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009, 75, 5544–5554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boone, S.A.; Gerba, C.P. Significance of fomites in the spread of respiratory and enteric viral disease. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007, 73, 1687–1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kampf, G. Persistence of coronaviruses on inanimate surfaces and their inactivation with biocidal agents. J. Hosp. Infect. 2020, 104, 246–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CDC. Candida Auris: A Drug-Resistant Germ That Spreads in Healthcare Facilities. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/fungal/candida-auris/index.html (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Thornton, C.; Johnson, E. Fungal infections in long-term care facilities. Med. Mycol. 2021, 59, 445–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, B. Air Sanitation via Multi-Recompressive Heating. Master’s Thesis, State University of New York at Buffalo, Buffalo and Amherst, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Leung, M.; Chan, A.H.S. Control and management of hospital indoor air quality. Med. Sci. Monit. 2006, 12, Sr17–Sr23. [Google Scholar]

- Donskey, C.J. Does improving surface cleaning and disinfection reduce health care-associated infections? Am. J. Infect. Control 2013, 41, S12–S19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, H.; Kreisel, D.; Hirano, R. Evaluation of airborne bacterial counts in operating rooms under standard ventilation conditions. Am. J. Infect. Control 2018, 46, 622–627. [Google Scholar]

- Weschler, C.J. Changes in indoor pollutants since the 1950s. Atmos. Environ. 2009, 43, 153–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douwes, J.; Thorne, P.; Pearce, N.; Heederik, D. Bioaerosol health effects and exposure assessment: Progress and prospects. Ann. Occup. Hyg. 2003, 47, 187–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweon, S.J.; Edmonds, S.L.; Kirk, J.; Rowland, D.Y.; Acosta, C. Effectiveness of a comprehensive hand hygiene program for reduction of infection rates in a long-term care facility. Am. J. Infect. Control 2013, 41, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mody, L.; McNeil, S.A.; Sun, R.; Bradley, S.F.; Kauffman, C.A. Introduction of a waterless alcohol-based hand rub in a long-term care facility. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2003, 24, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeung, W.K.; Tam, W.S.W.; Wong, T.W. Clustered randomized controlled trial of a hand hygiene intervention involving pocket-sized containers of alcohol-based hand rub for the control of infections in long-term care facilities. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2011, 32, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fendler, E.J.; Ali, Y.; Hammond, B.S.; Lyons, M.K.; Kelley, M.B.; Vowell, N.A. The impact of alcohol hand sanitizer use on infection rates in an extended care facility. Am. J. Infect. Control 2002, 30, 226–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makris, A.T.; Morgan, L.; Gaber, D.J.; Richter, A.; Rubino, J.R. Effect of a comprehensive infection control program on the incidence of infections in long-term care facilities. Am. J. Infect. Control 2000, 28, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haenen, A.; de Greeff, S.; Voss, A.; Liefers, J.; Hulscher, M.; Huis, A. Hand hygiene compliance and its drivers in long-term care facilities; observations and a survey. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2022, 11, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chemaly, R.F.; Simmons, S.; Dale, C.; Ghantoji, S.S.; Rodriguez, M.; Gubb, J.; Stachowiak, J.; Stibich, M. The role of the healthcare environment in the spread of multidrug-resistant organisms: Update on current best practices for containment. Ther. Adv. Infect. Dis. 2014, 2, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyce, J.M. Environmental contamination makes an important contribution to hospital infection. J. Hosp. Infect. 2007, 65, 50–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urrutia, A.R.; Schlener, S.D.; Eid, S.; Bock, K.A.; Worrilow, K.C. The Effects of an Advanced Air Purification Technology on Environmental and Clinical Outcomes in a Long-Term Care Facility. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2023, 78, 2325–2332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA). Electric Power Monthly, Table 5.3, June 2025. Available online: https://www.eia.gov/electricity/monthly/epm_table_grapher.php?t=epmt_5_06_b (accessed on 11 September 2025).

- Kowalski, W.J. Ultraviolet Germicidal Irradiation Handbook: UVGI for Air and Surface Disinfection; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers. Method of Testing General Ventilation Air-Cleaning Devices for Removal Efficiency by Particle Size; ASHRAE: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

| Test Objective(s) | Temperature (°C) | Challenge Organism(s) | Log or % Kill Rate | Representative Prototype Configurations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kill efficacy against bacteria | 240–247 | Bacillus globigii (Bg), Bacillus stearothermophilus (Bst) | >3–6 log (99.9–99.9999%) | Early prototypes (University at Buffalo, DoD GD450/GD540); all configurations achieved ≥99.9% kill |

| Kill efficacy against bacteria and virus | 240 | Bacillus globigii (Bg), Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt), E. coli, MS2 bacteriophage | >6 log (99.9999%) | DoD HF-408 prototypes (tri-lobe blower, counterflow heat exchanger); efficacy confirmed with mixed bacterial and viral challenge |

| Scaled airflow/system optimization | 220–240 | Bacillus globigii (Bg) | >6 log (99.9999%) | Optimized HF-408 prototypes (alpha/optimized flow configurations) and scaled 5000 CFM centrifugal system |

| Maintenance of kill efficacy (long-duration, scaled system) | 240 | Bacillus globigii (Bg) | >7 log (99.99999%) | 5000 CFM centrifugal counterflow system (DoD SBIR program) |

| Sampling Location | Bacteria (CFU/m3) | Fungi (CFU/m3) | Fungal Species (n) | Bacterial Species (n) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sitting Area | OVG | OVG | OVG | OVG |

| Front Exit | 35 | NGP | - | Bacillus sp. (5) |

| 10’ South of Front Exit | 57 | 7 | Auerobasidium sp. (1) | Bacillus sp. (3), Streptococcus sp. (2), Actinomycetes (1), Gram Neg Bacteria (1), Rhodococcus sp (1) |

| 20’ South of Front Exit | 21 | 14 | Cladosporium sp. (2) | Bacillus sp. (2), Streptococcus sp. (1) |

| Sink | 57 | 28 | Cladosporium sp. (4) | Bacillus sp. (3), Staphylococcus sp. (1), Streptococcus sp (1), Actinomycetes (2) |

| Kitchenette | 7 | 35 | Cladosporium sp. (5) | Bacillus sp. (5) |

| Average Concentration | 35 | 17 |

| Collection Date | Sample Location | Sample ID | Volume (L) | Count | Bacterial CFU/m3 | Bacterial Species Identified | Fungal Count | Fungal CFU/m3 | Fungal Species Identified |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 07/20/2023 | Supply 2—at outlet | 1 | 141.5 | NGP | - | - | 1 | 7 | Aspergillus fumigatus (1) |

| 07/20/2023 | Supply 2–6” from outlet | 2 | 141.5 | 1 | 7 | Bacillus sp. (1) | 4 | 28 | Aspergillus versicolor (1), Aspergillus niger (1), Alternaria alternata (2) |

| 07/20/2023 | Return 2–6” below diffuser | 3 | 141.5 | 1 | 7 | Actinomycete (1) | 7 | 50 | Acremonium (3), Aspergillus versicolor (1), Alternaria alternata (4) |

| Mean | <1 | <7 | 4 | 28 |

| Collection Date | Sample Location | Sample ID | Volume (L) | Count | CFU/m3 | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8/9/23 | Supply 2–at outlet | 1 | 141.5 | 0 | <7 | No Growth Promoted (NGP) |

| 8/9/23 | Return–at outlet | 1 | 141.5 | 0 | <7 | No Growth Promoted (NGP) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sharma, P.; Mahajan, S.; Morse, G.D.; Ward, R.L.; Sharma, S.; Schwartz, S.A.; Aalinkeel, R. Elimination of Airborne Microorganisms Using Compressive Heating Air Sterilization Technology (CHAST): Laboratory and Nursing Home Setting. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 2299. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13102299

Sharma P, Mahajan S, Morse GD, Ward RL, Sharma S, Schwartz SA, Aalinkeel R. Elimination of Airborne Microorganisms Using Compressive Heating Air Sterilization Technology (CHAST): Laboratory and Nursing Home Setting. Microorganisms. 2025; 13(10):2299. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13102299

Chicago/Turabian StyleSharma, Pritha, Supriya Mahajan, Gene D. Morse, Rolanda L. Ward, Satish Sharma, Stanley A. Schwartz, and Ravikumar Aalinkeel. 2025. "Elimination of Airborne Microorganisms Using Compressive Heating Air Sterilization Technology (CHAST): Laboratory and Nursing Home Setting" Microorganisms 13, no. 10: 2299. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13102299

APA StyleSharma, P., Mahajan, S., Morse, G. D., Ward, R. L., Sharma, S., Schwartz, S. A., & Aalinkeel, R. (2025). Elimination of Airborne Microorganisms Using Compressive Heating Air Sterilization Technology (CHAST): Laboratory and Nursing Home Setting. Microorganisms, 13(10), 2299. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13102299