d-Xylitol Production from Sugar Beet Press Pulp Hydrolysate with Engineered Aspergillus niger

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Fungal Strain

2.2. Sugar Beet Press Pulp Hydrolysate

2.3. Preculture, Inoculation, and Cultivation Medium

2.4. Cultivation in Stirred Tank Bioreactors

2.5. Quantification of Sugars and Organic Acids in Cultivation Supernatants

2.6. Gravimetric Determination of the Biomass Dry Weight

3. Results and Discussion

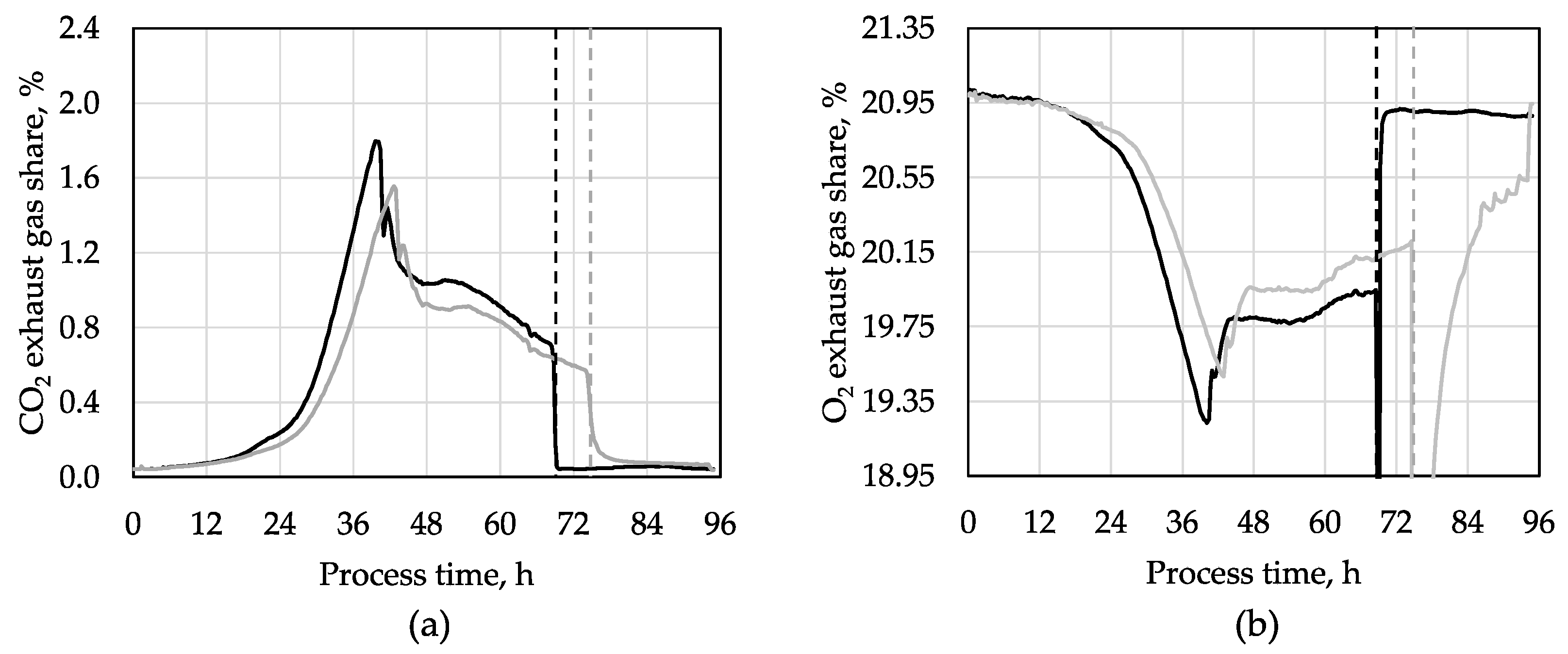

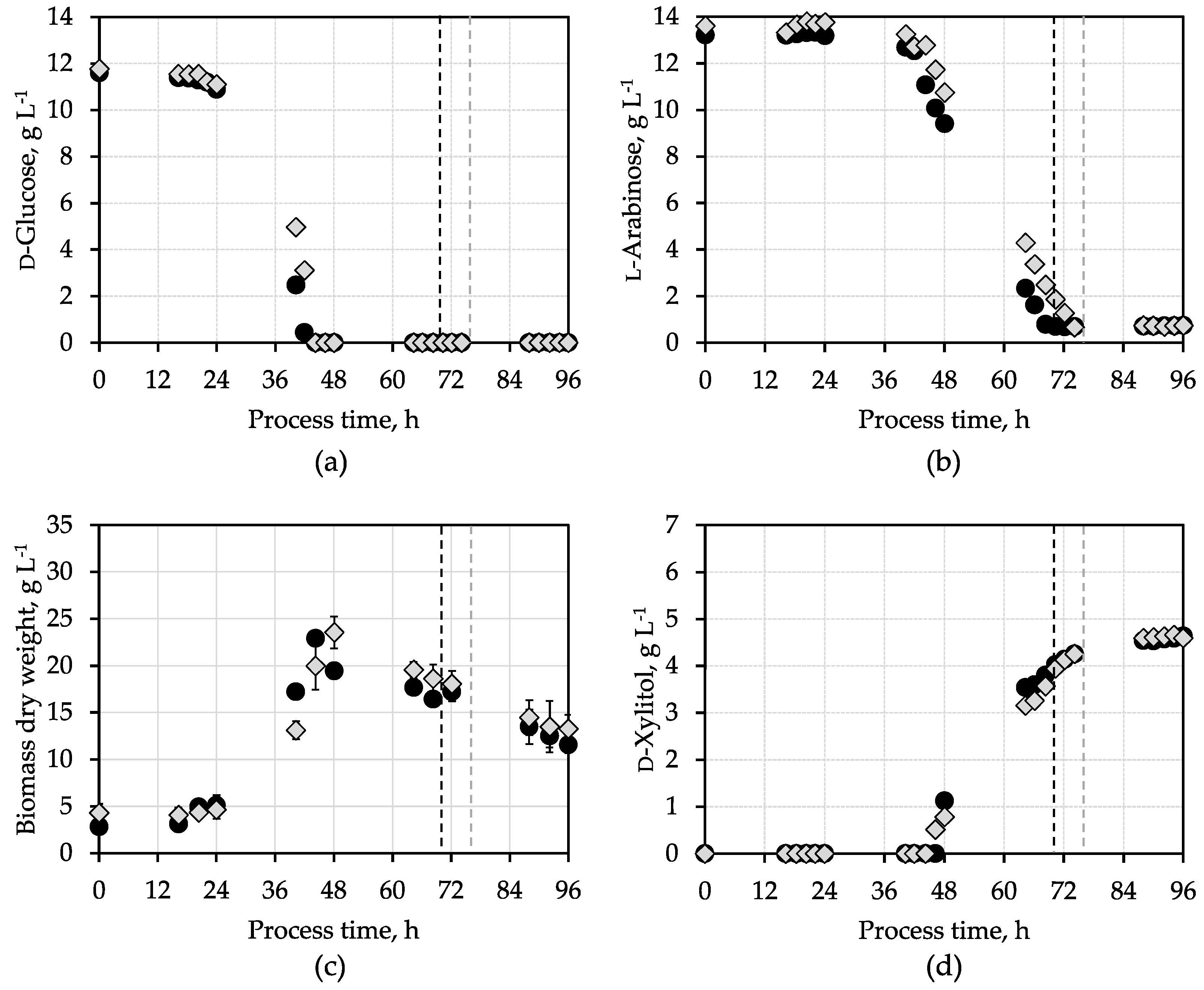

3.1. d-Xylitol Production with Synthetic Medium

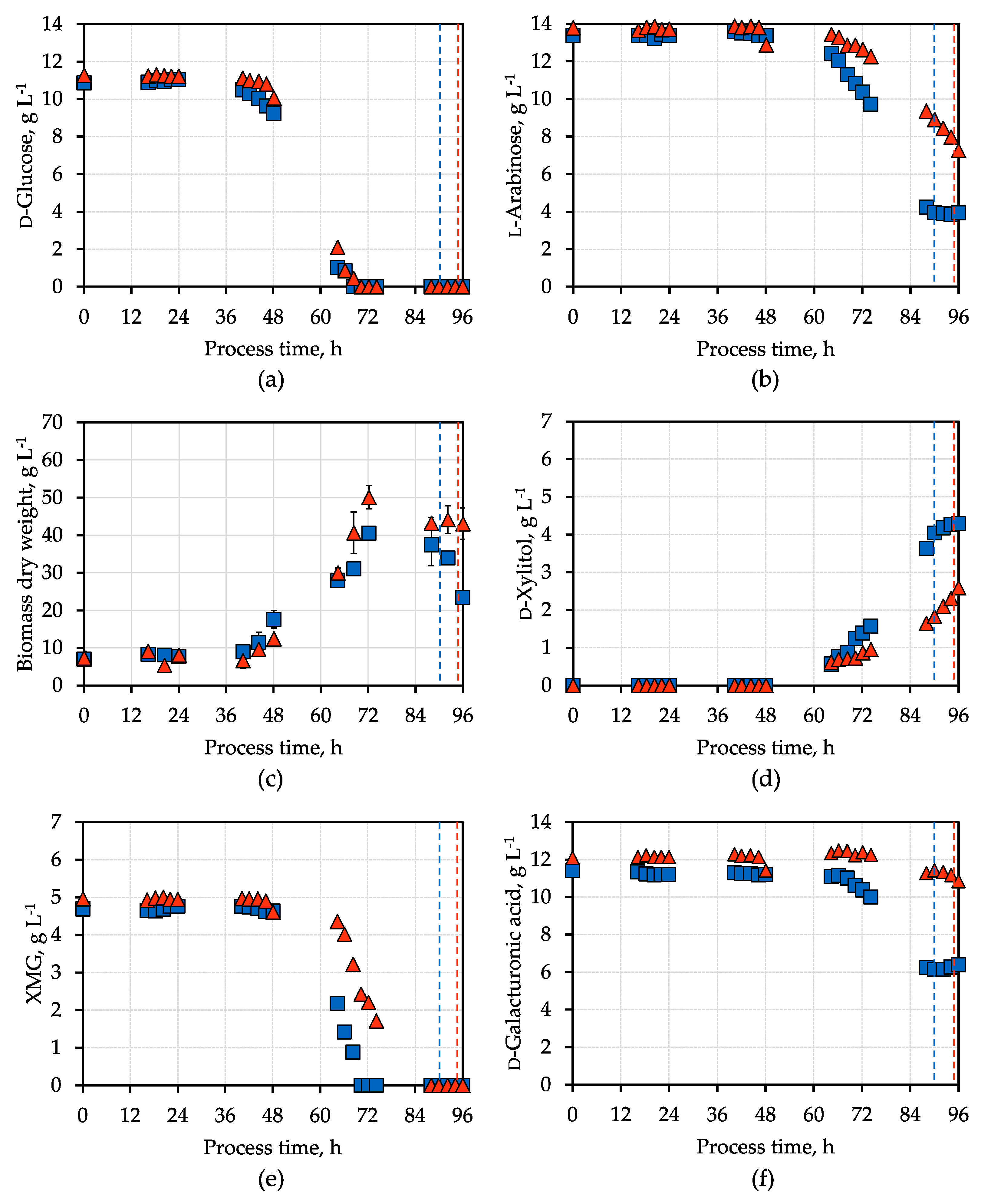

3.2. d-Xylitol Production Using SBPP Hydrolysate

3.3. d-Xylitol Production Using Activated Charcoal Pre-Treated SBPP Hydrolysate

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Holechek, J.L.; Geli, H.M.E.; Sawalhah, M.N.; Valdez, R. A Global Assessment: Can Renewable Energy Replace Fossil Fuels by 2050? Sustainability 2022, 14, 4792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasco-Muñoz, J.F.; Aznar-Sánchez, J.A.; López-Felices, B.; Román-Sánchez, I.M. Circular economy in agriculture. An analysis of the state of research based on the life cycle. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2022, 34, 257–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Önal, H. Renewable energy policies and competition for biomass: Implications for land use, food prices, and processing industry. Energy Policy 2016, 92, 270–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koul, B.; Yakoob, M.; Shah, M.P. Agricultural waste management strategies for environmental sustainability. Environ. Res. 2022, 206, 112285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, N.; Ghosh, S.K.; Bannerjee, S.; Aikat, K. Bioethanol production from agricultural wastes: An overview. Renew. Energy 2012, 37, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muir, B.M.; Anderson, A.R. Development and Diversification of Sugar Beet in Europe. Sugar Tech 2022, 24, 992–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Velásquez, C.; van der Meer, Y. Mind the Pulp: Environmental and economic assessment of a sugar beet pulp biorefinery for biobased chemical production. Waste Manag. 2023, 155, 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzo-Gago, C.; Díaz, A.B.; Blandino, A. Sugar Beet Pulp as Raw Material for the Production of Bioplastics. Fermentation 2023, 9, 655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knesebeck, M.; Schäfer, D.; Schmitz, K.; Rüllke, M.; Benz, J.P.; Weuster-Botz, D. Enzymatic One-Pot Hydrolysis of Extracted Sugar Beet Press Pulp after Solid-State Fermentation with an Engineered Aspergillus niger Strain. Fermentation 2023, 9, 582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harth, S.; Wagner, J.; Sens, T.; Choe, J.-Y.; Benz, J.P.; Weuster-Botz, D.; Oreb, M. Engineering cofactor supply and NADH-dependent D-galacturonic acid reductases for redox-balanced production of L-galactonate in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 19021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, J.; Schäfer, D.; von den Eichen, N.; Haimerl, C.; Harth, S.; Oreb, M.; Benz, J.P.; Weuster-Botz, D. D-Galacturonic acid reduction by S. cerevisiae for L-galactonate production from extracted sugar beet press pulp hydrolysate. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2021, 105, 5795–5807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vidal, L.M.; Wittkamp, T.; Benz, J.P.; Jekle, M.; Becker, T. A dynamic micro-scale dough foaming and baking analysis—Comparison of dough inflation based on different leavening agents. Food Res. Int. 2023, 164, 112342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gasmi Benahmed, A.; Gasmi, A.; Arshad, M.; Shanaida, M.; Lysiuk, R.; Peana, M.; Pshyk-Titko, I.; Adamiv, S.; Shanaida, Y.; Bjørklund, G. Health benefits of xylitol. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2020, 104, 7225–7237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathur, S.; Kumar, D.; Kumar, V.; Dantas, A.; Verma, R.; Kuca, K. Xylitol: Production strategies with emphasis on biotechnological approach, scale up, and market trends. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2023, 35, 101203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chroumpi, T.; Peng, M.; Aguilar-Pontes, M.V.; Müller, A.; Wang, M.; Yan, J.; Lipzen, A.; Ng, V.; Grigoriev, I.V.; Mäkelä, M.R.; et al. Revisiting a ‘simple’ fungal metabolic pathway reveals redundancy, complexity and diversity. Microb. Biotechnol. 2021, 14, 2525–2537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, J.; Chroumpi, T.; Mäkelä, M.R.; de Vries, R.P. Xylitol production from plant biomass by Aspergillus niger through metabolic engineering. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 344, 126199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rüllke, M.; Schönrock, V.; Schmitz, K.; Oreb, M.; Tamayo, E.; Benz, J.P. Engineering of Aspergillus niger for efficient production of D-xylitol from L-arabinose. Microb. Cell Fact. 2024, 23, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vishniac, W.; Santer, M. The thiobacilli. Bacteriol. Rev. 1957, 21, 195–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, H.; Barthel, L.; Schmideder, S.; Schütze, T.; Meyer, V.; Briesen, H. From spores to fungal pellets: A new high-throughput image analysis highlights the structural development of Aspergillus niger. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2022, 119, 2182–2195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafiqul, I.S.M.; Sakinah, A.M.M.; Zularisam, A.W. Inhibition by toxic compounds in the hemicellulosic hydrolysates on the activity of xylose reductase from Candida tropicalis. Biotechnol. Lett. 2015, 37, 191–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, M.A.; Mota, M.N.; Faria, N.T.; Sá-Correia, I. An Evolved Strain of the Oleaginous Yeast Rhodotorula toruloides, Multi-Tolerant to the Major Inhibitors Present in Lignocellulosic Hydrolysates, Exhibits an Altered Cell Envelope. JoF 2023, 9, 1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kühnel, S.; Schols, H.A.; Gruppen, H. Aiming for the complete utilization of sugar-beet pulp: Examination of the effects of mild acid and hydrothermal pretreatment followed by enzymatic digestion. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2011, 4, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aarabi, A.; Mizani, M.; Honarvar, M. The use of sugar beet pulp lignin for the production of vanillin. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 94, 345–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, G.; Sun, Y.; Guo, W.; Yuan, L. Comparison of various pretreatment strategies and their effect on chemistry and structure of sugar beet pulp. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 181, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Günan Yücel, H.; Aksu, Z. Ethanol fermentation characteristics of Pichia stipitis yeast from sugar beet pulp hydrolysate: Use of new detoxification methods. Fuel 2015, 158, 793–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, C.; Hartmann, D.O.; Varela, A.; Coelho, J.A.S.; Lamosa, P.; Afonso, C.A.M.; Silva Pereira, C. Securing a furan-based biorefinery: Disclosing the genetic basis of the degradation of hydroxymethylfurfural and its derivatives in the model fungus Aspergillus nidulans. Microb. Biotechnol. 2020, 13, 1983–1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arjeh, E.; Khodaei, S.M.; Barzegar, M.; Pirsa, S.; Karimi Sani, I.; Rahati, S.; Mohammadi, F. Phenolic compounds of sugar beet (Beta vulgaris L.): Separation method, chemical characterization, and biological properties. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 10, 4238–4246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabka, M.; Pavela, R. Antifungal efficacy of some natural phenolic compounds against significant pathogenic and toxinogenic filamentous fungi. Chemosphere 2013, 93, 1051–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, R.; Gautier, V.; Silar, P. Lignin degradation by ascomycetes. In Wood Degradation and Ligninolytic Fungi; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 77–113. ISBN 9780128216866. [Google Scholar]

- Brink, D.P.; Ravi, K.; Lidén, G.; Gorwa-Grauslund, M.F. Mapping the diversity of microbial lignin catabolism: Experiences from the eLignin database. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 103, 3979–4002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayet, A.; Teixeira, A.R.S.; Allais, F.; Bouix, M.; Lameloise, M.-L. Detoxification of highly acidic hemicellulosic hydrolysate from wheat straw by diananofiltration with a focus on phenolic compounds. J. Membr. Sci. 2018, 566, 112–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernal, M.; Ruiz, M.O.; Geanta, R.M.; Benito, J.M.; Escudero, I. Colour removal from beet molasses by ultrafiltration with activated charcoal. Chem. Eng. J. 2016, 283, 313–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Preechakun, T.; Pongchaiphol, S.; Raita, M.; Champreda, V.; Laosiripojana, N. Detoxification of hemicellulose-enriched hydrolysate from sugarcane bagasse by activated carbon and macroporous adsorption resin. Biomass Conv. Bioref. 2024, 14, 14559–14574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdez-Guzmán, B.E.; Rios-Del Toro, E.E.; Cardenas-López, R.L.; Méndez-Acosta, H.O.; González-Álvarez, V.; Arreola-Vargas, J. Enhancing biohydrogen production from Agave tequilana bagasse: Detoxified vs. Undetoxified acid hydrolysates. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 276, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dygas, D.; Kręgiel, D.; Berłowska, J. Sugar Beet Pulp as a Biorefinery Substrate for Designing Feed. Molecules 2023, 28, 2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martins, L.C.; Palma, M.; Angelov, A.; Nevoigt, E.; Liebl, W.; Sá-Correia, I. Complete Utilization of the Major Carbon Sources Present in Sugar Beet Pulp Hydrolysates by the Oleaginous Red Yeasts Rhodotorula toruloides and R. mucilaginosa. J. Fungi. 2021, 7, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regmi, P.; Knesebeck, M.; Boles, E.; Weuster-Botz, D.; Oreb, M. A comparative analysis of NADPH supply strategies in Sac-charomyces cerevisiae: Production of d-xylitol from d-xylose as a case study. Metab. Eng. Commun. 2024, 19, e00245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Arya, S.K.; Krishania, M. Insights into bioprocessed xylitol crystallization: Physico-chemical and techno-economic perspectives. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2024, 40, 101642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vardhan, H.; Sasamal, S.; Mohanty, K. Xylitol Production by Candida tropicalis from Areca Nut Husk Enzymatic Hydrolysate and Crystallization. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2023, 195, 7298–7321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Synthetic Medium | SBPP Hydrolysate Medium |

|---|---|---|

| Maximal CO2 value, % | 1.67 ± 0.13 | 1.71 (1.46) |

| Maximal CO2 value time, h | 42 ± 1 | 64 (61) |

| Maximal BDW concentration, g L−1 | 23.2 ± 0.3 | 40.5 ± 1.6 (50.1 ± 3.1) |

| Maximal BDW concentration time, h | 46 ± 2 | 72 (72) |

| Final d-xylitol concentration, g L−1 | 4.62 ± 0.02 | 4.3 (2.6) |

| Final d-xylitol yield, g g−1 | 0.36 ± 0.01 | 0.45 (0.4) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Knesebeck, M.; Rüllke, M.; Schönrock, V.; Benz, J.P.; Weuster-Botz, D. d-Xylitol Production from Sugar Beet Press Pulp Hydrolysate with Engineered Aspergillus niger. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 2489. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms12122489

Knesebeck M, Rüllke M, Schönrock V, Benz JP, Weuster-Botz D. d-Xylitol Production from Sugar Beet Press Pulp Hydrolysate with Engineered Aspergillus niger. Microorganisms. 2024; 12(12):2489. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms12122489

Chicago/Turabian StyleKnesebeck, Melanie, Marcel Rüllke, Veronika Schönrock, J. Philipp Benz, and Dirk Weuster-Botz. 2024. "d-Xylitol Production from Sugar Beet Press Pulp Hydrolysate with Engineered Aspergillus niger" Microorganisms 12, no. 12: 2489. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms12122489

APA StyleKnesebeck, M., Rüllke, M., Schönrock, V., Benz, J. P., & Weuster-Botz, D. (2024). d-Xylitol Production from Sugar Beet Press Pulp Hydrolysate with Engineered Aspergillus niger. Microorganisms, 12(12), 2489. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms12122489