High Clinical Burden of Cryptosporidium spp. in Adult Patients with Acquired Immunodeficiency in Ghana

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Population

2.2. Data Collection and Laboratory Methods

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Composition of the Study Population

3.2. Comparison of Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of the HIV Cohort According to Cryptosporidium spp. Status

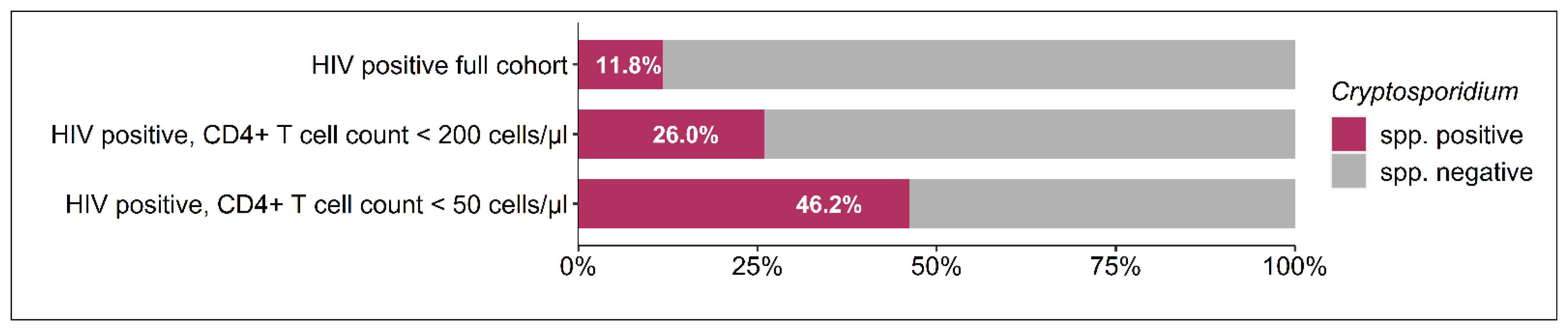

3.3. Comparison of Virological and Immunological Characteristics of the HIV Cohort According to Cryptosporidium spp. Status

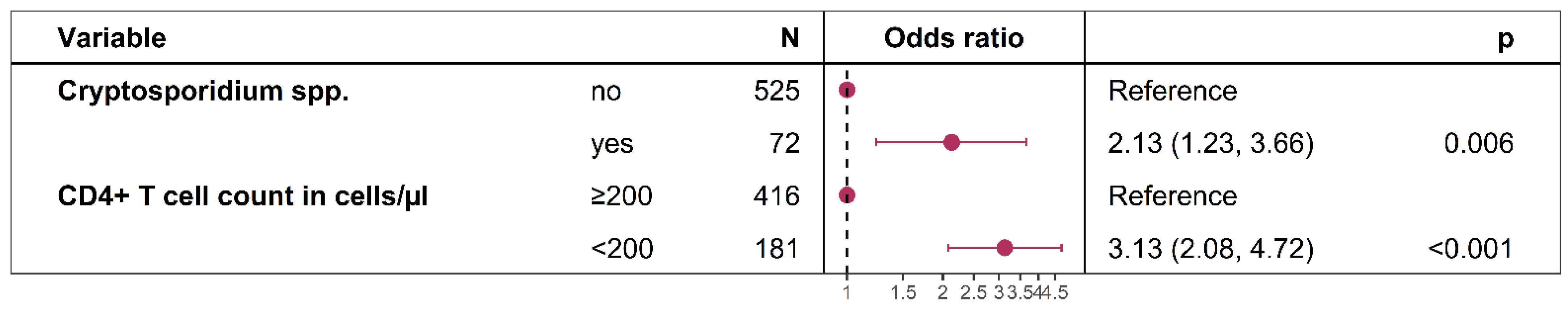

3.4. Factors Associated with the Reporting of Weight Loss During the Last Six Months in HIV-Positive Participants

3.5. Correlations of Cycle Threshold (Ct) Values with HIV Viral Load and CD4+ Cell Count

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Feng, Y.; Ryan, U.M.; Xiao, L. Genetic Diversity and Population Structure of Cryptosporidium. Trends Parasitol. 2018, 34, 997–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.-M.; Keithly, J.S.; Paya, C.V.; LaRusso, N.F. Cryptosporidiosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2002, 346, 1723–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Innes, E.A.; Chalmers, R.M.; Wells, B.; Pawlowic, M.C. A One Health Approach to Tackle Cryptosporidiosis. Trends Parasitol. 2020, 36, 290–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, U.; Hijjawi, N.; Xiao, L. Foodborne Cryptosporidiosis. Int. J. Parasitol. 2018, 48, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amadi, B.; Mwiya, M.; Sianongo, S.; Payne, L.; Watuka, A.; Katubulushi, M.; Kelly, P. High Dose Prolonged Treatment with Nitazoxanide Is Not Effective for Cryptosporidiosis in HIV Positive Zambian Children: A Randomised Controlled Trial. BMC Infect. Dis. 2009, 9, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maradana, M.R.; Marzook, N.B.; Diaz, O.E.; Mkandawire, T.; Diny, N.L.; Li, Y.; Liebert, A.; Shah, K.; Tolaini, M.; Kváč, M.; et al. Dietary Environmental Factors Shape the Immune Defense against Cryptosporidium Infection. Cell Host Microbe 2023, 31, 2038–2050.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colford, J.M., Jr.; Tager, I.B.; Hirozawa, A.M.; Lemp, G.F.; Aragon, T.; Petersen, C. Cryptosporidiosis among Patients Infected with Human Immunodeficiency Virus: Factors Related to Symptomatic Infection and Survival. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1996, 144, 807–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadpour, E.; Safarpour, H.; Xiao, L.; Zarean, M.; Hatam-Nahavandi, K.; Barac, A.; Picot, S.; Rahimi, M.T.; Rubino, S.; Mahami-Oskouei, M.; et al. Cryptosporidiosis in HIV-Positive Patients and Related Risk Factors: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Parasite 2020, 27, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohebali, M.; Yimam, Y.; Woreta, A. Cryptosporidium Infection among People Living with HIV/AIDS in Ethiopia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Pathog. Glob. Health 2020, 114, 183–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarfo, F.S.; Eberhardt, K.A.; Dompreh, A.; Kuffour, E.O.; Soltau, M.; Schachscheider, M.; Drexler, J.F.; Eis-Hübinger, A.M.; Häussinger, D.; Oteng-Seifah, E.E.; et al. Helicobacter Pylori Infection Is Associated with Higher CD4 T Cell Counts and Lower HIV-1 Viral Loads in ART-Naïve HIV-Positive Patients in Ghana. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0143388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jothikumar, N.; da Silva, A.J.; Moura, I.; Qvarnstrom, Y.; Hill, V.R. Detection and Differentiation of Cryptosporidium Hominis and Cryptosporidium Parvum by Dual TaqMan Assays. J. Med. Microbiol. 2008, 57, 1099–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weinreich, F.; Hahn, A.; Eberhardt, K.A.; Feldt, T.; Sarfo, F.S.; Di Cristanziano, V.; Frickmann, H.; Loderstädt, U. Comparison of Three Real-Time PCR Assays Targeting the SSU rRNA Gene, the COWP Gene and the DnaJ-Like Protein Gene for the Diagnosis of Cryptosporidium Spp. in Stool Samples. Pathogens 2021, 10, 1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niesters, H.G.M. Quantitation of Viral Load Using Real-Time Amplification Techniques. Methods 2001, 25, 419–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adamu, H.; Wegayehu, T.; Petros, B. High Prevalence of Diarrhoegenic Intestinal Parasite Infections among Non-ART HIV Patients in Fitche Hospital, Ethiopia. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e72634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omolabi, K.F.; Odeniran, P.O.; Soliman, M.E. A Meta-Analysis of Cryptosporidium Species in Humans from Southern Africa (2000–2020). J. Parasit. Dis. Off. Organ Indian Soc. Parasitol. 2022, 46, 304–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinyangwe, N.N.; Siwila, J.; Muma, J.B.; Chola, M.; Michelo, C. Factors Associated with Cryptosporidium Infection Among Adult HIV Positive Population in Contact with Livestock in Namwala District, Zambia. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyirenda, J.T.; Henrion, M.Y.R.; Nyasulu, V.; Msakwiza, M.; Nedi, W.; Thole, H.; Phulusa, J.; Toto, N.; Jere, K.C.; Winter, A.; et al. Examination of ELISA against PCR for Assessing Treatment Efficacy against Cryptosporidium in a Clinical Trial Context. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0289929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konadu, E.; Essuman, M.A.; Amponsah, A.; Agroh, W.X.K.; Badu-Boateng, E.; Gbedema, S.Y.; Boakye, Y.D. Enteric Protozoan Parasitosis and Associated Factors among Patients with and without Diabetes Mellitus in a Teaching Hospital in Ghana. Int. J. Microbiol. 2023, 2023, 5569262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, P.R.; Nichols, G. Epidemiology and Clinical Features of Cryptosporidium Infection in Immunocompromised Patients. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2002, 15, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boaitey, Y.A.; Nkrumah, B.; Idriss, A.; Tay, S.C.K. Gastrointestinal and Urinary Tract Pathogenic Infections among HIV Seropositive Patients at the Komfo Anokye Teaching Hospital in Ghana. BMC Res. Notes 2012, 5, 454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dankwa, K.; Nuvor, S.V.; Obiri-Yeboah, D.; Feglo, P.K.; Mutocheluh, M. Occurrence of Cryptosporidium Infection and Associated Risk Factors among HIV-Infected Patients Attending ART Clinics in the Central Region of Ghana. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2021, 6, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerace, E.; Lo Presti, V.D.M.; Biondo, C. Cryptosporidium Infection: Epidemiology, Pathogenesis, and Differential Diagnosis. Eur. J. Microbiol. Immunol. 2019, 9, 119–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iroh Tam, P.; Arnold, S.L.M.; Barrett, L.K.; Chen, C.R.; Conrad, T.M.; Douglas, E.; Gordon, M.A.; Hebert, D.; Henrion, M.; Hermann, D.; et al. Clofazimine for Treatment of Cryptosporidiosis in Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infected Adults: An Experimental Medicine, Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Phase 2a Trial. Clin. Infect. Dis. Off. Publ. Infect. Dis. Soc. Am. 2021, 73, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Opoku, Y.K.; Boampong, J.N.; Ayi, I.; Kwakye-Nuako, G.; Obiri-Yeboah, D.; Koranteng, H.; Ghartey-Kwansah, G.; Asare, K.K. Socio-Behavioral Risk Factors Associated with Cryptosporidiosis in HIV/AIDS Patients Visiting the HIV Referral Clinic at Cape Coast Teaching Hospital, Ghana. Open AIDS J. 2018, 12, 106–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backhaus, J.; Kann, S.; Hahn, A.; Weinreich, F.; Blohm, M.; Tanida, K.; Feldt, T.; Sarfo, F.S.; Di Cristanziano, V.; Loderstädt, U.; et al. Clustering of Gastrointestinal Microorganisms in Human Stool Samples from Ghana. Pathogens 2024, 13, 583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samie, A.; Makuwa, S.; Mtshali, S.; Potgieter, N.; Thekisoe, O.; Mbati, P.; Bessong, P.O. Parasitic Infection among HIV/AIDS Patients at Bela-Bela Clinic, Limpopo Province, South Africa with Special Reference to Cryptosporidium. Southeast Asian J. Trop. Med. Public Health 2014, 45, 783–795. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | HIV Positive Cryptosporidium spp. Positive, n = 73 (11.81%) | HIV Positive Cryptosporidium spp. Negative, n = 545 (88.19%) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | Age in years ± SD | 41.0 ± 10.7 | 40.4 ±9.3 | 0.656 |

| Female, n (%) | 50 (69.44) | 400 (75.19) | 0.365 | |

| Socioeconomic parameters | Access to tap water, n (%) | 39 (54.17) | 280 (52.63) | 0.905 |

| Electricity in household, n (%) | 68 (94.44) | 496 (93.23) | 1.000 | |

| Television in household, n (%) | 59 (81.94) | 434 (81.58) | 1.000 | |

| Refrigerator in household, n (%) | 57 (79.17) | 381 (71.62) | 0.228 | |

| Owning a car, n (%) | 8 (11.11) | 51 (9.59) | 0.843 | |

| Medical therapy | HIV diagnosis since < 1 month, n (%) | 43 (66.15) | 164 (34.02) | <0.001 |

| TMP/SMX prophylaxis, n (%) | 29 (40.85) | 165 (31.67) | 0.158 | |

| Intake of cART, n (%) | 11 (15.28) | 241 (45.30) | <0.001 | |

| Months since initiation of cART, median (IQR) | 60.9 (37.2 to 71.9) | 50.9 (23.8 to 79.3) | 0.537 |

| Variable | HIV Positive cART Exposed | HIV Positive cART Naïve | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cryptosporidium spp. Positive, Median (IQR), n = 11 (4.37%) | Cryptosporidium spp. Negative, Median (IQR), n = 241 (95.63%) | p-Value | Cryptosporidium spp. Positive, Median (IQR), n = 61 (17.33%) | Cryptosporidium spp. Negative, Median (IQR), n = 291 (82.67) | p-Value | |

| Viral load, log10 copies/mL | 3.4 (2.1–4.7) | 1.6 (0.0–1.8) | 0.001 | 5.5 (5.0–5.8) | 5.0 (4.2–5.5) | <0.001 |

| CD4+ T cell count/µL | 345.0 (180.0–654.5) | 503.0 (312.8–702.5) | 0.225 | 76.0 (30.0–217.0) | 266.0 (112.0–466.0) | <0.001 |

| CD8+ T cell count/µL | 967.5 (726.0–1584.5) | 918.0 (652.5–1288.5) | 0.536 | 927.0 (523.0–1328.5) | 1022.5 (672.2–1573.5) | 0.273 |

| CD4+/CD8+ T cell ratio | 0.2 (0.1–0.5) | 0.5 (0.4–0.9) | 0.014 | 0.1 (0.0–0.2) | 0.3 (0.1–0.5) | <0.001 |

| Ct Values of the Real-Time PCR Targeting Cryptosporidium spp. | ||

|---|---|---|

| Spearman’s Rho | p-Value | |

| CD4+ T cell count/µL | 0.488 | <0.001 |

| Viral load, log10 copies/mL | −0.244 | 0.045 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sarfo, F.S.; Frickmann, H.; Dompreh, A.; Osei Asibey, S.; Boateng, R.; Weinreich, F.; Osei Kuffour, E.; Norman, B.R.; Di Cristanziano, V.; Feldt, T.; et al. High Clinical Burden of Cryptosporidium spp. in Adult Patients with Acquired Immunodeficiency in Ghana. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 2151. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms12112151

Sarfo FS, Frickmann H, Dompreh A, Osei Asibey S, Boateng R, Weinreich F, Osei Kuffour E, Norman BR, Di Cristanziano V, Feldt T, et al. High Clinical Burden of Cryptosporidium spp. in Adult Patients with Acquired Immunodeficiency in Ghana. Microorganisms. 2024; 12(11):2151. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms12112151

Chicago/Turabian StyleSarfo, Fred Stephen, Hagen Frickmann, Albert Dompreh, Shadrack Osei Asibey, Richard Boateng, Felix Weinreich, Edmund Osei Kuffour, Betty Roberta Norman, Veronica Di Cristanziano, Torsten Feldt, and et al. 2024. "High Clinical Burden of Cryptosporidium spp. in Adult Patients with Acquired Immunodeficiency in Ghana" Microorganisms 12, no. 11: 2151. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms12112151

APA StyleSarfo, F. S., Frickmann, H., Dompreh, A., Osei Asibey, S., Boateng, R., Weinreich, F., Osei Kuffour, E., Norman, B. R., Di Cristanziano, V., Feldt, T., & Eberhardt, K. A. (2024). High Clinical Burden of Cryptosporidium spp. in Adult Patients with Acquired Immunodeficiency in Ghana. Microorganisms, 12(11), 2151. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms12112151