Abstract

The fungal order Entomophthorales in the Zoopagomycota includes many fungal pathogens of arthropods. This review explores six genera in the subfamily Erynioideae within the family Entomophthoraceae, namely, Erynia, Furia, Orthomyces, Pandora, Strongwellsea, and Zoophthora. This is the largest subfamily in the Entomophthorales, including 126 described species. The species diversity, global distribution, and host range of this subfamily are summarized. Relatively few taxa are geographically widespread, and few have broad host ranges, which contrasts with many species with single reports from one location and one host species. The insect orders infected by the greatest numbers of species are the Diptera and Hemiptera. Across the subfamily, relatively few species have been cultivated in vitro, and those that have require more specialized media than many other fungi. Given their potential to attack arthropods and their position in the fungal evolutionary tree, we discuss which species might be adopted for biological control purposes or biotechnological innovations. Current challenges in the implementation of these species in biotechnology include the limited ability or difficulty in culturing many in vitro, a correlated paucity of genomic resources, and considerations regarding the host ranges of different species.

1. Introduction

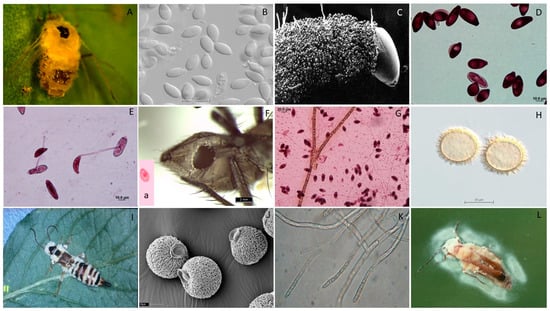

The fungal order Entomophthorales in the Zoopagomycotina includes at least 246 species of arthropod pathogens [1], many of which are well known for their ability to cause epizootics and change the behavior of infected hosts [2]. Their role in biocenoses is extremely important because they can function as regulators of arthropod populations and thus play a role in ecosystem homeostasis. Within the Entomophthorales, the largest family is the Entomophthoraceae, which consists exclusively of arthropod pathogens. This family was divided into two subfamilies in 2005, the Entomophthoroideae and the Erynioideae [3]. The Erynioideae is the larger of these two subfamilies, containing six genera, namely Erynia, Furia, Orthomyces, Pandora, Strongwellsea, and Zoophthora. Fungi in these genera have diverse ecological, physiological, and morphological adaptations (Figure 1) and evolved to infect a wide range of arthropod species using their ballistic conidia. Their hosts inhabit diverse ecosystems, including agriculture and forestry. In particular, Erynioideae infect insects that are recognized as pests of various important crops worldwide [4,5,6]. In addition to attacking arthropod pests directly damaging crops and forests, some of the arthropod hosts of species in this subfamily include vectors of diseases that impact humans, livestock, and crops.

Figure 1.

Examples showing the diversity of EFOPSZ cell types and hosts. Aphid infected with Zoophthora radicans (A). Pandora cacopsyllae primary conidia, typical for this genus morphology (B). Pandora sciarae conidiophores covering the body of a fungus gnat (C). Primary and secondary conidia of Pandora neoaphidis (D). Germination of Z. radicans primary conidia with secondary conidia (E). Cadaver of Delia radicum with abdominal hole where Strongwellsea sp. primary conidia are actively discharged (F); single nuclear conidium (a). Nuclear stain of P. neoaphidis primary conidia (G). Strongwellsea selandia round resting spores with spines (H). White layer of Zoophthora forficulae conidiophores penetrating whole earwigs cadaver except thick cuticular plates and limbs (I). Incrustation of the Zoophthora independentia resting spores (J). Septation of the Z. radicans vegetative mycelium (K). Whitish “halo” of the Pandora lipai conidia discharged from the whitish/yellowish conidiophore layer covered the soldier beetle (L).

Due to the observed capability of Entomophthorales to cause massive mortality of insect hosts, questions about their potential use for biocontrol and various biotechnological applications are often raised. Exotic strains and species have been released for classical biocontrol of diverse insects in many countries, with some successful establishments and pest control [7]. However, presently, no species of Entomophthorales are commercially available as biopesticides. Species within this group differ from one another in numerous ways that impact their potential development as biopesticides [8]. One of the most important attributes to consider in this regard is the cultivability of these fungal species in vitro, which plays a critical factor in their propagation for potential application as biological control agents. This feature can be expressed to various degrees: from total inability to isolate fungal strains in vitro to routine transfers of the isolates and preservation of their cultures in culture collections to research on improving in vitro growth toward potential mass production. Additionally, for successful biological control, the host range of the pathogens must be known and is crucial in both identifying suitable fungi for specific target pests as well as in avoiding potential impacts on non-target arthropods. Furthermore, the natural habitats of these fungi and their geographical distributions are important for consideration of development for biological control as regions around the world differ in the regulation of species to be used for pest control that are native vs. non-native [9]. In addition, knowledge of the habitats where these fungi are naturally active will provide information about their ecological adaptability and long-term survival under diverse conditions.

The primary objective of this research was to characterize several critical aspects of the lifestyles of the species within the six genera in the Erynioideae, here referred to by the acronym EFOPSZ. An overall consideration of the species in this group has not previously been undertaken. We have analyzed these vital characteristics for species of the Erynioideae, and we aim to pinpoint which species demonstrate the most potential for future use in biological control. Moreover, we are keen on identifying the specific insect groups for which the application of these species as biological control agents might be most successful. We predict that the assembly of this new information could be important for potential applications of this group in various aspects of biotechnology, particularly in the development of biological control agents for pest management.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature Analysis

We sought all literature related to the six genera in the Erynioideae through the use of the Web of Science, Scopus, and Google Scholar, examining publications since 1888 [10] using keywords and names of genera included in this study. We also examined the information associated with the species and strains deposited in the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service Collection of Entomopathogenic Fungal Cultures (ARSEF, Ithaca, NY, USA); the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA); and CBS-Westerdijk Institute KNAW Fungal Biodiversity Centre, also known as Central Bureau of Fungal Cultures (Utrecht, Netherlands). The traits that were investigated are geographical distribution, host range, type of habitat, and documented ability to grow in vitro.

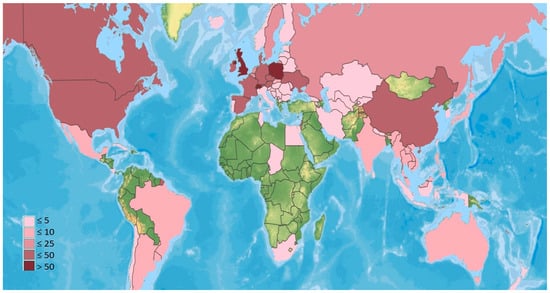

2.2. Distribution Map

A map of the number of recorded species was created using StepMap GmbH software (Berlin, Germany). Countries and regions were colored according to the number of recorded species from lightest (less than 5 species) to darkest (over 50 species described) pink. Green indicates none have been reported. We consider the species as (1) local if the distribution range covers only one continent, (2) cosmopolitan or broadly distributed with records on at least two continents, and (3) ubiquitous if distribution records cover three or more continents.

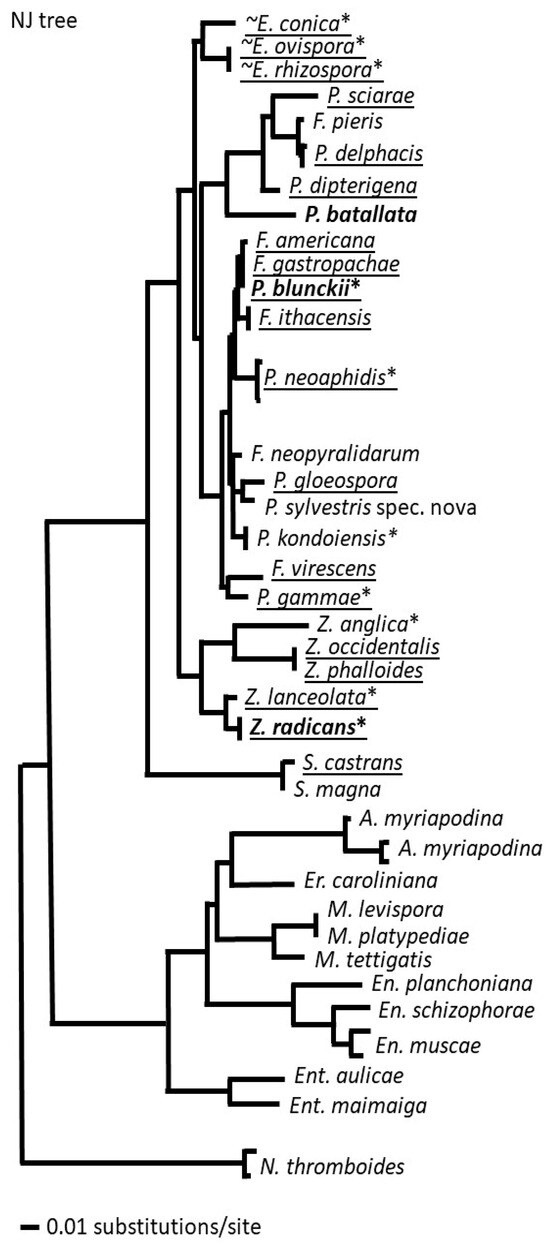

2.3. Phylogenetic Tree

To generate a dataset of EFOPSZ taxa, we downloaded 18S and 28S sequences of identified species with accurate nomenclature from GenBank. All sequences were initially aligned, their alignments were manually adjusted, and ambiguous regions were excluded from the alignments using Mesquite 3.04 version [11]. Phylogenetic relationships were determined by the neighbor-joining (NJ) algorithm, and the tree was visualized in PAUP* 4.0 [12].

3. Results

3.1. Geographic Distribution

Species in the EFOPSZ group have been recorded from all continents except Antarctica. However, the number of described species differs significantly between countries and regions (Figure 2). The most records are from several Central European countries (especially Switzerland and Poland) and the United Kingdom. Many species have also been found in North America (USA and Canada), other European countries, and China. Only a handful of reports are from South America and across a considerable area of Asia and Oceania. The continent least documented for these fungi is Africa, where EFOPSZ fungi have been reported from only four countries. They are also sparsely reported in countries in South America other than Argentina, Brazil, and Chile and are reported from a few countries in the Middle East. However, the map in Figure 2 most likely does not represent the actual species distributions but rather the situation regarding our knowledge of this fungal group in particular countries where more sampling has occurred. It is obvious that climatic conditions in many countries of Africa or South America might be very favorable for species in the Erynioideae, but little research has yet been undertaken to describe Erynioideae and their host ranges from these regions.

Figure 2.

Number of EFOPSZ species recorded for different countries. Green indicates none reported.

There were clear differences in patterns of species distribution among the six genera. Each genus contains both ubiquitous and cosmopolitan species as well as local ones, and they are not grouped in any specific way on the phylogenetic tree (Figure 2). It is very possible that many of the species of these genera that we classify as local have much broader distributions but have not been sampled broadly. We consider the broad distributions of many species as advantageous for future biocontrol agents since this feature might indicate a significant level of adaptability and ability to survive the environmental conditions in different climatic environments due to their ecology, pathogenesis, and specialization [13].

Another perspective on geographical distribution can be obtained from analyzing culture collection deposits. The largest insect pathogen collection in the world is the USDA/ARS entomopathogenic fungi collection (ARSEF), which includes almost 15,000 occurrence records [14]. Although ARSEF has deposits from all over the world, most samples are from the USA and then from Europe. We hypothesize that isolates from the rest of the world are less represented due to a lack of sampling. Despite the scarcity of well-recorded data, at least 53 species out of the 125 valid EFOPSZ species might be considered as cosmopolitan, and at least 25 as ubiquitous (Figure 3, Table 1). Many of these might become ubiquitous due to the worldwide nature of human agricultural activities, which spread many crops worldwide along with their pests. One of the best examples of a human-mediated distribution might be Pandora gloeospora, found on several continents in mushroom-growing farms [15].

Figure 3.

A phylogenetic tree of species in the genera Erynia, Furia, Pandora, Strongwellsea, and Zoophthora of the subfamily Erynioideae: ~—aquatic or moist habitats, *—cultivable; generalists in bold, ubiquitous species underlined. Members of the Entomophthoroideae and genus Neoconidiobolus are provided as outgroups.

Table 1.

Geographic distributions and arthropod hosts of EFOPSZ fungi.

3.2. Host Specificity

EFOPSZ fungi show a range of host-specificity. One-third of EFOPSZ parasitize two or more insect families. The species Erynia conica, E. rhizospora, E. selpulchralis, P. batallata, P. blunckii, P. echinospora, P. nouryi, Z. aphidis, Z. canadensis are pathogenic to representatives of at least two families. An absolute generalist is Z. radicans, which infects insects in 7 orders and 21 families (Table 1). However, two-thirds of EFOPSZ fungal species show some host-specificity and can infect only a narrower range of insects, usually attacking members of the same genus or family.

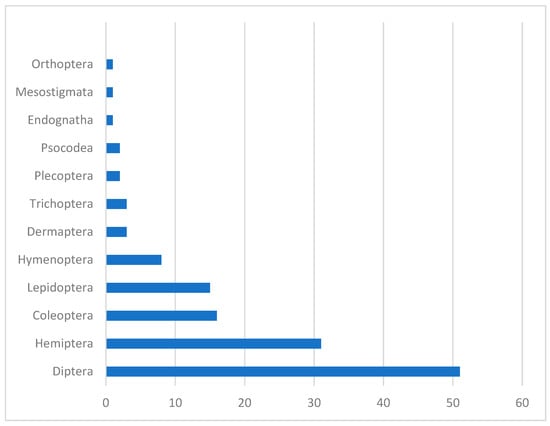

The flies (order Diptera) are the most frequent hosts for EFOPSZ fungi, as more than one-third of these fungal species were found killing Diptera. Nearly 25 percent of EFOPSZ fungi infect insects in the order Hemiptera (31 pathogenic species), and nearly half that number were found infecting Coleoptera (16 pathogens) and Lepidoptera (15 pathogens). Within the Diptera, families most attacked by EFOPSZ fungi are Calliphoridae (eight pathogen species); Tipulidae (seven); Muscidae, Psychodidae, and Sciaridae (six each); and Chironomidae (five). In the genus Strongwellsea, species specialize exclusively in four dipteran families: Anthomyiidae, Muscidae, Sarcophagidae, and Scatophagidae. Among Hemiptera, the families Aphididae (14), Miridae (7), and Cicadellidae (6) are most infected by EFOPSZ fungi. All other insect families have less than five pathogenic EFOPSZ species infecting them (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

How many EFOPSZ species infect different arthropod orders.

3.3. Biological and Ecological Characteristics of EFOPSZ Fungi as Biocenose Components

Most species in the Erynioideae primarily infect insects in natural and agricultural environments. These habitats include aquatic biocenoses, forests and natural areas, and agrocenoses. It might be more precise to discuss the distribution of insect hosts, even if fungal infections can lead to infected insects relocating from their typical habitats [86]. Many EFOPSZ species infect the imago (adult stage) of hosts. Among holometabolous hosts, species in the genus Strongwellsea only infect adults, while some species from the other genera infect larvae or nymphs. No EFOPSZ species have been found attacking insect eggs.

These different host life cycle stages may occur in various ecosystems, so this factor should also be considered. In most cases, infected insects are found and collected on plant parts, partly due to the so-called climbing effect caused by many EFOPSZ fungi [166]. This altered behavior may also be attributed to better visibility for researchers compared to the soil surface beneath vegetation. A comprehensive analysis of the distribution of entomophthoralean fungi in European biocenoses, focusing on forests and agrocenoses, was carried out by Bałazy [17]. Bałazy’s analysis emphasizes the importance of insect mobility, particularly because many insect hosts have wings and can migrate to neighboring ecosystems, spreading infection. This mobility is supported by the collection of dispersing aphids infected with P. neoaphidis [167] and the isolation of P. delphacis from planthoppers caught on a weather ship off the coast of Japan [76].

Most EFOPSZ fungi are prevalent in aboveground ecosystems. The cadavers of insects infected with EFOPSZ are often found on wild and cultured plants in various ecosystems. The presence of representatives of the genus Zoophthora, in particular, is well-documented in numerous agricultural crops, orchards, and different types of forests. Species like P. dipterigena, P. philonthi, Z. anglica, Z. miridis, Z. opomyzae, Z. petchii, Z. phytonomi, and Z. radicans are commonly observed in annual and perennial crops, meadows, pastures, orchards, and forests. These species seem to be well-adapted to drier habitats. Species of the genera Strongwellsea and Zoophthora appear to be the most adaptable to a wide range of habitats, whether natural or human created. Furthermore, aphid pathogenic species, like P. neoaphidis and P. nouryi, have been found worldwide in many crops and are commonly observed at different temperatures and humidities.

All Entomophthorales require high humidity to release and disperse their conidia [168]. Interestingly, half of the species in the genus Erynia were found in aquatic or notably moist areas, e.g., E. aquatica, E. conica, E. curvispora, E. nematoceris, E. ovispora, E. sepulchralis, and E. variabilis. These species may serve as efficient biological control agents for insects requiring aquatic habitats during specific life stages due to their higher humidity needs compared to other species in this group. Additionally, five species in the genus Pandora, one species in Furia, and one species in Zoophthora were found in moist habitats. However, no Strongwellsea species were recorded in explicitly aquatic or moist environments (Table 1).

Soil is an unusual habitat for predominantly insect-pathogenic EFOPSZ. Nevertheless, at least one species, Pandora nouryi, infects root aphids (Pemphigus) and follows its hosts to this habitat, becoming a soil dweller [78]. Zoophthora myrmecophaga infects ants that move along their paths on the soil surface. Pandora brahminae, which infects scarabs inhabiting the soil surface, also might be considered soil inhabitants.

3.4. Cultivability

Few species in the EFOPSZ group have been isolated into pure culture or even had their cultivability tested. Most species have been described only from insect cadavers, and there are no cultures preserved. The USDA ARSEF culture collection contains fungal strains isolated from infected insects. While most strains belong to the Ascomycota, entomophthoralean fungi are also well represented. This collection preserves 683 total isolates of EFOPSZ [14]. These include 28 species known in the genera Erynia, Furia, Pandora, Strongwellsea, and Zoophthora, as well as 36 isolates from these 5 genera, which are not yet identified at the species level. Most species are represented by a single or just a few isolates. However, there are over a hundred isolates representing species such as P. neoaphidis and Z. radicans, which reflects the common occurrence and easy cultivability of those species.

Few EFOPSZ fungi can be cultivated on typical fungal nutritional media such as malt extract or potato dextrose agar or in the corresponding liquid media [168]. In the past, to ensure the fungal growth of entomopathogens, special media containing animal protein from additives such as liver, extracts of fresh or dried insects, blood serum, or egg yolk were used [23,169], providing the pathogens with specific nutrients absent in the usual laboratory media. Sometimes rare and exotic media components such as fly fat bodies are used to stimulate spore germination or hyphal growth. The addition of yeast extract, arginine, or other amino acids to the medium substantially improves the growth of entomophthoralean fungi. Nowadays, the most used liquid medium for entomophthoralean growth is Grace′s Insect Medium (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), often with additives such as fetal bovine serum (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

Larger-scale production using simpler media has been developed for a few species. A method for producing Z. radicans dry-formulated mycelium has been developed with sporulation equivalent to cadavers. Recent examples of successful production on a large laboratory scale of the fungus P. cacopsyllae are the studies by Muskat et al. ([170,171], in press). This fungus that infects psyllids of the genus Cacopsylla has been fermented, encapsulated, and tested for above-ground application.

The most fastidious EFOPSZ species can so far only be cultured in vivo. They require the maintenance of an insect colony either in the laboratory or in the natural environment to maintain their population and complete their life cycle. The best results are obtained from using the natural hosts of the pathogenic fungus. In vivo production is the most difficult and labor-intensive method for growing entomopathogenic fungi.

The ability to grow EFOPSZ in culture is often connected with the ability of these fungi to infect insects at various stages of their life cycle, or at least stages other than the imago (adult), as seen in species like E. curvispora, Z. bialovienzenzis, Z. lanceolata, Z. phytonomi, and Z. radicans [17,23]. One of the remarkable characteristics of EFOPSZ fungi, particularly those with high-host or life-stage specificity, is the loss of their vigor and viability after several transfers on laboratory media despite strong initial growth [168,172]. These features of highly host-specific members of the EFOPSZ can pose a challenge to mass production in biotechnology.

3.5. Molecular Data, Genomics, and Biotechnology

Molecular data have been obtained for only ca. one-fifth of Erynioideae species, which has complicated their identification. Most available data used for the molecular taxonomy of this fungal group are the small (18S) and large (28S) RNA subunit sequences, which are successfully used to build phylogenetic trees and provide molecular identification of species (e.g., see Figure 2). The most frequently used primers are LROR and LR3 or LR5 (28S) and NSSU1088r and NS24 (18S). Amplification of the internal subscribed spacer (ITS) region, which is usually used as a barcoding gene for fungal species identification, can be challenging in the case of the Erynioideae, possibly because of its length, which varies from 0.9 to 1.3 k nucleotides in known species using the typical fungal barcode primers ITS1f and ITS4. However, partial ITS sequences (ITS2 region) were used to genotype the species of Strongwellsea and describe several new species of this genus [128,129,131,132]. Pandora formicae, P. gammae, P. kondoiensis, P. neoaphidis, P. nouryi, and Zoophthora radicans have also been genotyped with ITS sequences [86,173,174,175,176]. Some species have information available for genes encoding elongation factor 1-alpha, RNA polymerase II subunits (RPB1 and RPB2), mitochondrial small subunit ribosomal RNA, white collar-1 protein, beta-tubulin (btub), elongation factor 1 alpha-like protein (efl), cell division control protein 25 (CDC25), chitin synthase (CHS3), chitin deacetylase (CHD1), chitinase 1 (CHI1), endochitinase (CHT1), triacylglycerol lipase (LIP2), glucan binding protein (GBP1), subtilisin-like protease precursor (SPR2), polyketide synthase (PKS), triacylglycerol lipase precursor (LIP1), trypsin-like serine protease precursor (TRY1). The most intensively genotyped species are definitely P. neoaphidis and Z. radicans, from which most of the aforementioned gene fragments have been obtained [174,175,177,178,179,180,181,182,183]; these species have also been considered the most promising agents for biocontrol. Zoophthora radicans transcriptomes were also extensively investigated in regard to fungal pathogenicity [184]. As an example of limited genetic information, no DNA sequence information is available from the single species in the genus Orthomyces.

In addition to using these species directly for biological control, other potential biotechnology applications based on the use of genes or proteins derived from these fungi have yet to be explored. The early diverging lineages of fungi, here defined as the paraphyletic group, not including the Dikarya (e.g., Ascomycota and Basidiomycota), have emerged through the characterization of their genomes as distinct among fungi in containing numerous genes and traits shared with animals that were lost in more derived members of the Dikarya. Such homologs may, in the future, provide new insights into fundamental biology or even lead to therapeutics for human health. Entomopathogenic fungi themselves are well known to produce diverse small-molecule secondary metabolites/natural products with activity against insects [185]. Genome sequences have revealed evidence of greater biosynthetic capability for such molecules, even among some lineages of early diverging fungi [186], and the potential for EFOPSZ fungi has not been thoroughly explored. Additionally, entomopathogens, including some in Entomophthorales, also produce protein toxins that show insecticidal activity [187,188].

At present, just a single species from the Erynioideae has had its genome sequenced, i.e., Z. radicans [189]; this was possible in part due to the ease of its cultivability. The genome was generated as part of a large collection of species in a study that addressed the ploidy levels of the early fungal lineages, and so features about what this genome contains have not been described yet in detail. This genome sequence carries the information for how Z. radicans completes its lifecycle, including as an entomopathogen, but the mechanism is not immediately obvious. The Z. radicans genome is large, with the assembly at over 650 Mb currently divided over nearly 7000 scaffolds and estimated to encode over 14,000 genes. The large size is due to the large amount of repetitive DNA within the genome (Figure 5). The entomopathogens in the Hypocreales (Ascomycota) contain numerous gene clusters for the synthesis of secondary metabolites, one of the best known being the cluster for the immunosuppressive cyclosporin from Tolypocladium inflatum [190], as well as other types of toxins (e.g., enterotoxins) with possible roles in altering host behavior [191]. However, such detailed information based on the Z. radicans genome is not yet available, and a cursory examination of the genome indicates no examples of gene clusters for the synthesis of toxins.

As pointed out above, one challenge toward generating more genome sequences is being able to obtain sufficient DNA, usually through culturing of isolates in vitro, which has not been possible for many of these species. Difficulties with culturing EFOPSZ fungi make sequencing their genomes complicated because of the challenge of isolating high-quality and high-molecular-weight DNA and RNA for sequencing. For many species, extraction of total DNA from the host insect cadaver might be the only option. However, the recent advances in single-cell genomics [192] may provide a way in the near future to generate more genomic information about the genetic composition and potential virulence factors of EFOPSZ species. Once identified, these genetic components could be utilized in vector-based expression systems for application as biopesticides. There are also a few genomes available for the closely related subfamily—the Entomophthoroideae—including Entomophthora muscae, Entomophaga maimaiga, Massospora cicadina, as well as other species in Entomophthorales: Conidiobolus coronatus, Neoconidiobolus thromboides, and Basidiobolus meristosporus [193]. Summarizing genome features for the available entomophthoralean genomes, it can be predicted that the genomes of most EFOPSZ fungi are much larger compared to the average ascomycete fungal genome size (40–60 kB) and can reach 600,000–1,000,000 kB in size and consist of many duplicated gene copies and repeated regions [194].

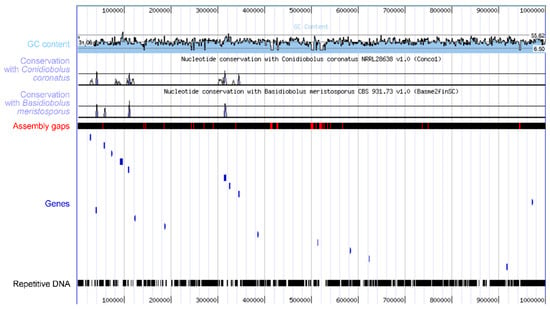

Figure 5.

The Z. radicans genome features large amounts of repetitive DNA between coding regions. This figure is a modified version of the MycoCosm [195] visualization of 1 Mb of sequence on contig 1, showing in blue only 17 genes across the region, separated by repetitive DNA in black. Conservation of DNA sequences with two other sequenced species in the Entomophthorales is low.

4. Discussion

The goal of using entomopathogenic fungi in various biotechnological applications, particularly to control populations of agricultural insect pests, has existed for several decades. However, entomophthoralean species have not been successfully developed and applied for biological control despite numerous attempts. The major challenges in their application as biocontrol agents include the difficulty with the cultivation of many species, requirements for specific abiotic conditions in the field, and the potentially low survival rates of these fungi outside of the host. However, EFOPSZ fungi possess significant potential, which is still largely unexplored. Recent advances in genome sequencing technologies may allow researchers to access key genetic factors that are involved in virulence against insect hosts, even in those EFOPSZ species that cannot be easily cultivated, and biotechnology could then potentially be used to deploy these in various ways for pest control.

The ability of entomophthoralean species to infect insects from different families or even from different orders increases the diversity of target insect species for developing efficient biocontrol measures and selection of suitable pests to control. At the same time, the broad host ranges of some of these fungi make use of newly developed biological control remedies riskier as they may also affect non-target insects, including those that are beneficial for natural ecosystems and humans.

While further research investigating host range among EFOPSZ is needed, the search for potential biocontrol agents within the Erynioideae might use information on current host ranges and distributions, targeting hosts belonging to insect taxonomic groups that are known to be attacked by EFOPSZ (Table 1). Even more important, prediction of possible non-targets of entomopathogenic species should account for insects within those same taxonomic groups in addition to pollinators and other beneficials. To some extent, it is an advantage if a species already has been found on several continents and thus might be adapted and developed for use in biocontrol over a larger area. These species, with high adaptability to various environments, are promising candidates for targeting widespread insect hosts. Each genus of the EFOPSZ group has several species that are distributed on at least three continents: in the genus Erynia, E. aquatica, E. conica, E. ovispora, and E. rhizospora; in the genus Furia, F. americana, F. gastropachae, F. ithacensis, and F. virescens; and in the genus Pandora, P. blunckii, P. bullata, P. delphacis, P. dipterigena, P. gammae, P. neoaphidis, and P. nouryi. Many ubiquitous species are included in the genus Zoophthora: Z. aphidis, Z. geometralis, Z. occidentalis, Z. phalloides, Z. phytonomi, and Z. radicans. Two species of Strongwellsea, S. castrans and S. magna, have been found on two continents. With increasing research on entomophthoralean fungi, we hypothesize that it is likely that a larger number of ubiquitous species will be identified.

Representatives of the genera Erynia, Pandora, and Zoophthora are among the important infective agents of insects under field conditions. The attempts at the introduction of EFOPSZ species on different continents have had success with Z. radicans in Australia using a strain originated from Israel to control the spotted alfalfa aphid, Therioaphis maculata [78].

A lower need for humidity could be considered an advantageous feature for potential biological control preparations using EFOPSZ species. Aquatic species like E. aquatica might be successfully used only in wet habitats where they are highly adapted to the moist environment, and this could restrict application compared to the species found in diverse ecosystems. The broad ecological and geographical range of Z. radicans, recorded from numerous agricultural and natural habitats, makes this species unique within the EFOPSZ.

Cultivability is perhaps the main factor that determines the potential success of any biotechnological application with EFOPSZ. If the fungus is hard to cultivate on artificial media, then the only way to apply it as a biocontrol agent is to keep it in vivo, infecting the insect population either in nature or under lab conditions. However, this is costly, cumbersome, and risky. Development of the biotechnological process and especially scaling it up demands easy culturing without losing virulence. The challenges of isolation into a pure culture of the majority of EFOPSZ species, along with loss of vigor during numerous culture transfers, significantly complicate the research on and development of potential biocontrol.

A problem with successful pest control with many fungi is the level of susceptibility of the active organisms to external factors, such as fluctuations in temperature, humidity, and rainfall. Climate changes may significantly impact the relationship between fungi, insects, and crops and the interactions among them [196]. Furthermore, additional information needed for the eventual production of EFOPSZ as biopesticides would be the development of optimal methods for formulation and application.

5. Conclusions

Analysis of the available data on virulence, growth in vivo and in vitro, formulation, and field testing suggests that one promising candidate for the development of efficient biological control agents would be the species Z. radicans. This species seems to have the potential to control a range of lepidopteran larvae in many agricultural and forest ecosystems. Another species, P. neoaphidis, has great potential for control of numerous aphid species in cereals and legumes. Of special importance is the worldwide distribution of aphids impacting crops and, thus, the large market that exists. In orchards, P. cacopsyllae has recently been proven to possess a potential for control of psyllid pests. A major objective here is that fruits are high-value crops that may favor biocontrol options. For the moist and aquatic habitats, there are several species infecting dipterans. Erynia aquatica and E. conica may have the potential for mosquito control; however, little is known about their virulence and growth in vitro. Obviously, the aforementioned factors are not the only factors determining the success or failure of biocontrol development; however, they play essential roles. However, advances in genome sequencing methods may allow researchers to access virulence factors and other genetic factors of these fungi that could be harnessed for future biotechnological solutions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.P.G. and A.E.H.; methodology, A.P.G., A.E.H., A.I. and K.E.B.; validation, Y.N., A.E.H., A.P.G. and A.I.; investigation, N.V., L.K., K.E.B., J.E., Y.N., R.G.M., V.B.K. and F.A.; resources, A.E.H., Y.N., K.E.B., A.I., R.G.M. and J.E.; data curation, A.P.G., N.V., Y.N., R.G.M., L.K., A.I., K.E.B. and A.E.H.; writing—original draft preparation, A.P.G., A.E.H., A.I. and K.E.B.; visualization, K.E.B., A.E.H., A.P.G., J.E., R.G.M. and A.I.; supervision, A.E.H. and Y.N.; funding acquisition, Y.N., A.I., J.E., R.G.M. and A.P.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported in part by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, and National Natural Science Foundation of China (Project No. 32370007). A.I. was supported by the Hermon Slade Foundation (HSF22060).

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to Lucas Beagle, Division 30, and the leadership of UESInc., for the possibility of conducting and publishing this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Sacco, N.E.; Hajek, A.E. Diversity and Breadth of Host Specificity among Arthropod Pathogens in the Entomophthoromycotina. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajek, A.E.; Eilenberg, J. Natural Enemies: An Introduction to Biological Control, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2018; Available online: http://find.library.duke.edu/catalog/DUKE010116949 (accessed on 2 January 2024).

- Keller, S.; Petrini, O. Keys to the identification of the arthropod pathogenic genera of the families Entomophthoraceae and Neozygitaceae (Zygomycetes), with descriptions of three new subfamilies and a new genus. Sydowia 2005, 57, 23–53. [Google Scholar]

- Steinkraus, D.C.; Oliver, J.B.; Humber, R.A.; Gaylor, M.J. Mycosis of bandedwinged whitefly (Trialeurodes abutilonea) (Homoptera: Aleyrodidae) caused by Orthomyces aleyrodis gen. & sp. nov. (Entomophthorales: Entomophthoraceae). J. Invertebr. Pathol. 1998, 72, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, P.A.; Pell, J.K. Entomopathogenic fungi as biological control agents. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2003, 61, 413–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, J.P.M.; Hughes, D.P. Chapter One—Diversity of Entomopathogenic Fungi: Which Groups Conquered the Insect Body. In Advances in Genetics; Lovett, B., St Leger, R.J., Eds.; Genetics and Molecular Biology of Entomopathogenic Fungi; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016; Volume 94, pp. 1–39. [Google Scholar]

- Hajek, A.E.; Gardescu, S.; Delalibera, I.J. Classical Biological Control of Insects and Mites: A Comprehensive List of Pathogen and Nematode Introductions. Cornell University Library. 2020. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/1813/69611 (accessed on 2 January 2024).

- Bamisile, B.S.; Siddiqui, J.A.; Akutse, K.S.; Ramos Aguila, L.C.; Xu, Y. General Limitations to Endophytic Entomopathogenic Fungi Use as Plant Growth Promoters, Pests and Pathogens Biocontrol Agents. Plants 2021, 10, 2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barratt, B.I.P. Assessing safety of biological control introductions. CABI Rev. 2012, 2011, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaxter, R. The Entomophthoreae of the United States. Harv. Bot. Mem. 1888, 2, 133–201. [Google Scholar]

- Madisson, W.P.; Madisson, D.R. Mesquite: A Modular System for Evolutionary Analysis. Version 3.04. Mesquite Project. Available online: https://www.mesquiteproject.org/ (accessed on 2 January 2024).

- Swofford, D.L. PAUP*: Phylogenetic Analysis Using Parsimony (and Other Methods) Version 4.0 Beta 10; Sinauer Associates: Sunderland, MA, USA, 2002; 143p. [Google Scholar]

- Lovett, B.; St Leger, R.J. The Insect Pathogens. Microbiol. Spectr. 2017, 5, 10–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ARSEF ARSEF Catalogues: USDA ARS. Available online: https://www.ars.usda.gov/northeast-area/ithaca-ny/robert-w-holley-center-for-agriculture-health/emerging-pests-and-pathogens-research/docs/mycology/page-2-arsef-catalogues/ (accessed on 31 October 2023).

- Miller, M.W.; Keil, C.B. Redescription of Pandora gloeospora (Zygomycetes: Entomophthorales) from Lycoriella mali (Diptera: Sciaridae). Mycotaxon 1990, 38, 227–231. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, J.F.; Rongo, S.Z. Entomophthora aquatica sp. n. infecting larvae and pupae of floodwater mosquitoes. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 1969, 13, 386–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bałazy, S. Flora of Poland. Fungi (Mycota), Entomophthorales; Polish Academy of Sciences, W. Szafer Institute of Botany: Kraków, Poland, 1993; Volume 24. [Google Scholar]

- Gustafsson, M. On the species of the genus Entomophthora Fr. in Sweden. 1. Classification and distribution. Lantbrukshögsk Ann. 1965, 31, 103–121. [Google Scholar]

- Gustafsson, M. On species of the genus Entomophthora Fres. in Sweden. III. Possibility of usage in biological control. Lantbrukshögsk Ann. 1969, 35, 235–274. [Google Scholar]

- Keller, S. Arthropod-pathogenic Entomophthorales from Switzerland. III. First additions. Sydowia 2007, 59, 75–113. [Google Scholar]

- Keller, S. Arthropod-pathogenic Entomophthorales of Switzerland. II. Erynia, Eryniopsis, Neozygites, Zoophthora and Tarichium. Sydowia 1991, 43, 39–122. [Google Scholar]

- Keller, S.; Dhoi, Y.G.C. Insect pathogenic Entomophthorales from Nepal and India. Mitt. Schweiz. Entomol. Ges. 2007, 80, 211–215. [Google Scholar]

- Koval, E.Z. Flora Fungorum Ucrainical. Zygomycotina. Entomophthorales; National Academy of Sciences: Kyiv, Ukraine, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- MacLeod, D.M.; Müller-Kögler, E. Entomogenous fungi: Entomophthora species with pear-shaped to almost spherical conidia (Entomophthorales: Entomophthoraceae). Mycologia 1973, 65, 823–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niell, M.; Santamaria, S. Additions to the knowledge of Entomopathogenic Entomophthorales (Fungi, Zygomycota) from Spain. Nova Hedwig. 2001, 73, 167–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, M.Z.; Li, Z.Z. Two new pathogens of dipteran insects. Mycotaxon 1994, 50, 307–314. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, M.Z.; Li, Z.Z. Erynia chironomis, comb. nov. (Zygomycetes: Entomophthorales). Mycotaxon 1995, 53, 369. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.Z. Flora Fungorum Sinicorum. Entomophthorales; Science Press: Beijing, China, 2000; Volume 13. [Google Scholar]

- Bałazy, S. On some little known epizootics in noxious and beneficial arthropod populations caused by entomophthoralean fungi. IOBC WPRS Bull. 2003, 21, 63–68. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Ze’ev, I.S.; Zelig, Y.; Bitton, S.; Kenneth, R.G. The entomophthorales of Israel and their arthropod hosts: Additions 1980–1988. Phytoparasitica 1988, 16, 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evlakhova, A.A. Entomopathogenic Fungi; Nauka: Moscow, Russia, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Hutchison, J.A. The Genus Entomophthora in the Western Hemisphere. Trans. Kans. Acad. Sci. 1963, 66, 237–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koval, E.Z. Identification of Entomophilic Fungi of the USSR; Naukova Dumka: Kyiv, Ukraine, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Leatherdale, D. The arthropod hosts of entomogenous fungi in Britain. Entomophaga 1970, 15, 419–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadeau, M.P.; Dunphy, G.B.; Boisvert, J.L. Entomopathogenic fungi of the order Entomophthorales (Zygomycotina) in adult black fly populations (Diptera: Simuliidae) in Quebec. Can. J. Microbiol. 1994, 40, 682–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.Z.; Chen, Z.A.; Xu, Y.W. Erynia gigantea, a new pathogen of spittlebug, Aphrophora sp. Acta Mycol. Sin. 1990, 9, 263–265. [Google Scholar]

- Zha, L.-S.; Wen, T.-C.; Hyde, K.D.; Kang, J.-C. An updated checklist of fungal species in Entomophthorales and their host insects from China. Mycosystema 2016, 35, 666–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, S. New records of Entomophthoraceae (Fungi, Zygomycetes) from aquatic insects. Mitt. Schweiz. Entomol. Ges. 2005, 78, 333–336. [Google Scholar]

- Humber, R.A.; Ben-Ze`ev, I. Erynia (Zygomycetes: Entomophthorales): Emendation, Synonymy, and Transfers. Mycotaxon 1981, XIII, 506–516. [Google Scholar]

- Keller, S.; Hülsewig, T. Amended description and new combination for Entomophthora nebriae Raunkiaer, (1893), a little known entomopathogenic fungus attacking the ground beetle Nebria brevicollis (Fabricius, 1792). Alp. Entomol. 2018, 2, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Tkaczyk, C.; Bałazy, S.; Krzyczkowski, T.; Wegensteiner, R. Extended studies on the diversity of arthropod-pathogenic fungi in Austria and Poland. Acta Mycol. 2011, 46, 211–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, C.S. Morphology of Pandora dipterigena collected from Lucilia sericata. Chin. J. Vec. Biol. Contr. 2010, 21, 546–548. [Google Scholar]

- Keller, S. Arthropod-pathogenic Entomophthorales from Switzerland. IV. Second addition. Mitt. Schweiz. Entomol. Ges. 2012, 85, 115–130. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.J.; Li, Z.Z. Furia fujiana, a new pathogen of pale-lined tiger moth, Spilarctia obliqua. Acta Mycol. Sin. 1993, 12, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Filotas, M.J.; Hajek, A.E.; Humber, R.A. Prevalence and biology of Furia gastropachae (Zygomycetes: Entomophthorales) in populations of forest tent caterpillar (Lepidoptera: Lasiocampidae). Can. Entomol. 2003, 135, 359–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacLeod, D.M.; Tyrrell, D. Entomophthora crustosa n. sp. as a pathogen of the forest tent caterpillar, Malacosoma disstria (Lepidoptera: Lasiocampidae). Can. Entomol. 1979, 111, 1137–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Moraes, R.R.; Loeck, A.E.; Berlamino, L.C. Inimigos Naturais de Rachiplusia nu (Guenée, 1852) e de Pseudoplusia includens (Walker, 1857) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) em Soja no Rio Grande so Sul.—Portal Embrapa. Pesq. Agropec. Bras. 1991, 26, 57–64. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.J.; Zheng, B.N.; Li, Z.Z. Natural and induced epizootics of Erynia ithacensis in mushroom hothouse populations of yellow-legged fungus gnats. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 1992, 60, 254–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Ze`ev, I. Erynia neopyralidarum sp. nov. and Conidiobolus apiculatus, pathogens of pyralid moths components of the misdescribed species, Entomophthora pyralidarum (Zygomycetes: Entomophthorales). Mycotaxon 1982, 16, 273–292. [Google Scholar]

- Pena, R.M.C.; Kunimi, Y.; Motobayashi, T.; Endoh, Y.; Numazawa, K.; Aoki, J. Erynia neopyralidarum Ben-Ze’ev (Zygomycetes: Entomophthorales) Isolated from the Mulberry Tiger Moth, Spilosoma imparilis Butler (Lepidoptera: Arctiidae) in Japan. Appl. Entomol. Zool. 1990, 25, 503–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Wang, X.F.; Li, Z.H.; Xu, W.A.; Sheng, C.F. Survey of entomophthoralean fungi in Shandong. Entomol. Knowl. 2004, 41, 350–353. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.Z.; Fan, M.Z.; Huang, B. New combinations of entomophthoralean fungi originally in the genus Erynia. Mycosystema 1998, 17, 91–94. [Google Scholar]

- Villacarlos, L.; Wilding, N. Four new species of Entomophthorales infecting the leucaena psyllid Heteropsylla cubana in the Philippines. Mycol. Res. 1994, 98, 153–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lednev, G.R. Pathogens of the Insect Mycoses. Diagnostics Manual; Innovation Center of All-Russian Institute of Plant Protection Ltd.: Saint Petersburg, Russia, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Steinkraus, D.C.; Mueller, A.J.; Humber, R.A. Furia virescens (Thaxter) Humber (Zygomycetes: Entomophthoraceae) Infections in the Armyworm, Pseudaletia unipuncta (Haworth) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) in Arkansas with Notes on Other Natural Enemies. J. Entomol. Sci. 1993, 28, 376–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Peña, S.R. Entomopathogens from two Chihuahuan desert localities in Mexico. BioControl 2000, 45, 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villacarlos, L.T.; Mejia, B.S. Philippine entomopathogenic fungi I. Occurrence and diversity. Philipp. Agric. Sci. 2004, 87, 249–265. [Google Scholar]

- Keller, S.; Hülsewig, T.; Jensen, A.B. Fungi attacking springtails (Sminthuridae, Collembola) with a description of Pandora batallata, sp. nov. (Entomophthoraceae). Sydowia 2022, 75, 37–45. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Ze’ev, I.; Kenneth, R.G.; Bitton, S. The Entomophthorales of Israel and their arthropod hosts. Phytoparasitica 1981, 9, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, M.Z.; Guo, C.; Liu, R.G.; Li, D.J.; Wang, C.J. New record genus Strongwellsea and Pandora blunckii in China. J. Northeast. Univ. 1992, 7, 26–30. [Google Scholar]

- Guzman-Franco, A.; Clark, S.; Alderson, P.; Pell, J. Effect of temperature on the in vitro radial growth of Zoophthora radicans and Pandora blunckii, two co-occurring fungal pathogens of the diamondback moth Plutella xylostella. BioControl 2007, 53, 501–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Liu, J.N.; Wu, Q.Q.; Wang, S.B.; Cai, R.S.; Huang, B. Investigation of Entomophthoralean resourse in Hefei. J. Anhui Agric. Univ. 2000, 27, 240–242. [Google Scholar]

- Tomiyama, H.; Aoki, J. Infection of Erynia blunkii (Lak. ex. Zimm.) Rem. et Henn. (Entomophthorales: Entomophthoraceae) in the diamondback moth, Plutella xylostella L. (Lepidoptera: Yponomeutidae). Appl. Entomol. Zool. 1982, 17, 373–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villacarlos, L. Updated records of Philippine Entomophthorales. Philipp. Entomol. 2008, 22, 22–52. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, M.Z.; Guo, C.; Li, Z.Z. New species and a new record of the genus Erynia in China. Acta Mycol. Sin. 1991, 10, 95–100. [Google Scholar]

- MacLeod, D.M.; Tyrrell, D.; Soper, R.S.; De Lyzer, A.J. Entomophthora bullata as a pathogen of Sarcophaga aldrichi. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 1973, 22, 75–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glare, T.R.; Milner, R.J. New Records of Entomophthoran Fungi from Insects in Australia. Aust. J. Bot. 1987, 35, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, S. Taxonomic considerations on some species of Erynia (Zygomycetes: Entomophthorales) attacking flies (Diptera). Sydowia 1993, 45, 252–263. [Google Scholar]

- Zangeneh, S.; Ghazavi, M. New Records of Entomophthoralean Fungi from Iran. Rostaniha 2008, 9, 190–203. [Google Scholar]

- Montalva, C.; Collier, K.; Luz, C.; Humber, R.A. Pandora bullata (Entomophthoromycota: Entomophthorales) affecting calliphorid flies in central Brazil. Acta Trop. 2016, 158, 177–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eilenberg, J.; Keller, S.; Humber, R.A.; Jensen, A.H.; Jensen, A.B.; Görg, L.M.; Muskat, L.C.; Kais, B.; Gross, J.; Patel, A.V. Pandora cacopsyllae Eilenberg, Keller & Humber (Entomophthorales: Entomophthoraceae), a new species infecting pear psyllid Cacopsylla pyri L. (Hemiptera: Psyllidae). J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2023, 200, 107954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humber, R.A. Synopsis of a revised classification for the Entomophthorales (Zygomycotina). Mycotaxon 1989, 34, 441–460. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, M.K.; Harper, J.D. Occurrence of Erynia delphacis in the threecornered alfalfa hopper, Spissistilus festinus (Homoptera: Membracidae). J. Invertebr. Pathol. 1987, 50, 81–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.Z.; Fan, M.Z.; Qin, C.F. New species and new records of Entomophthorales in China. Acta Mycol. Sin. 1992, 11, 182–187. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz, G.M.I. Pandora Delphacis (Entomophthorales: Entomophthoraceae) an Entomopathogenic Fungus of the Threecornered Alfalfa Hopper, Spissistilus Festinus (Homoptera: Membracidae); University of Arkansas ProQuest Dissertations Publishing: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1995; Available online: https://www.proquest.com/openview/74cf7739893ac6f070c578200c04fcfc/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y (accessed on 25 August 2023).

- Takehiko, M.; Hiroki, S.; Mitsuaki, S. Isolation of an entomogenous fungus, Erynia delphacis (Entomophthorales: Entomophthoraceae), from migratory planthoppers collected over the Pacific Ocean. Appl. Entomol. Zool. 1998, 33, 545–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Foieri, A.; Pedrini, N.; Toledo, A. Natural occurrence of the entomopathogenic genus Pandora on spittlebug pests of crops and pastures in Argentina. J. Appl. Entomol. 2017, 142, 363–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barta, M.; Cagáň, L. Aphid-pathogenic Entomophthorales (their taxonomy, biology and ecology). Biologia 2006, 61, S543–S616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barta, M.; Cagáň, L. Observations on the Occurrence of Entomophthorales Infecting Aphids (Aphidoidea) in Slovakia. BioControl 2006, 51, 795–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Ze’ev, I.S. Check-list of fungi pathogenic to insects and mites in Israel, updated through 1992. Phytoparasitica 1993, 21, 213–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.J.; Zheng, B.N. A new record species of Erynia from China. Acta Mycol. Sin. 1990, 9, 327–328. [Google Scholar]

- Méndez-Sánchez, S.E.; Freitas, A.L.; de Almeida, C.S.; Silva, G.B.; Lima, L.S. Levantamiento preliminar de hongos entomophthorales (Zygomycotina: Zygomycetes), agentes de control natural de insectos al sur de Bahia, Brasil. Agrotropica 2002, 14, 77–80. [Google Scholar]

- Remaudière, G.; Latge, J.P. Importancia de los hongos patógenos de insectos (especialmente Aphididae y Cercopidae) en Méjico y perspectivas de uso. Bol. Sanid. Veg. Plagas 1985, 11, 217–225. [Google Scholar]

- Young, A.M.; Tyrrell, D.; MacLeod, D.M. Entomophthora echinospora (Phycomycetes: Entomophthoraceae), a fungus pathogenic on the neotropical cicada, Procollina biolleyi (Homoptera: Cicadidae). J. Invertebr. Pathol. 1973, 21, 87–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baiswar, P.; Firake, D.M. First record of Pandora formicae on ant, Camponotus angusticollis and Batkoa amrascae on white leaf hopper, Cofana spectra in rice agroecosystem of India. J. Eco-Friendly Agric. 2022, 17, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Małagocka, J.; Jensen, A.B.; Eilenberg, J. Pandora formicae, a specialist ant pathogenic fungus: New insights into biology and taxonomy. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2017, 143, 108–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, G.G.; Carner, G.R. Factors affecting the spore form of Entomophthora gammae. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 1975, 26, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscardi, F.; Correra Ferreira, B.S.; Hoffmann-Campo, C.B.; de Oliveira, E.B.; Boucias, D.G. Ocorrência de Entomopatogenos em Lepidópteros Que Atacam a Cultura da Soja no Paraná, Presented at the Congresso Brasiliero de Entomologia; Resumos: Londrina, PR, Brazil, 1984; Volume 9, p. 143. [Google Scholar]

- DIez, S.L.; Gamundi, J.C. Empleo de enfermedades como método de biocontrol de insectos plagas. Tecnol. Para El Campo INTA 1985, 10, 19–20. [Google Scholar]

- Samson, R.A.; Evans, H.C.; Latgé, J.-P. Atlas of Entomopathogenic Fungi; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edelstein, J.D.; Lecuona, R.E. Presencia del hongo entomopatógeno Pandora gammae (Weiser) Humber (Zygomycetes: Entomophthorales), en el complejo de “orugas medidoras de la soja” (Lepidoptera: Plusiinae) en Argentina. RIA. Rev. De Investig. Agropecu. 2003, 32, 31–38. [Google Scholar]

- López Lastra, C.C.; Scorsetti, A.C. Hongos patógenos de insectos en Argentina (Zygomycetes: Entomophthorales. Rev. Biol. Trop. 2006, 54, 311–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López Lastra, C.C.; Scorsetti, A.C. Revisión de los hongos Entomophthorales (Zygomycota: Zygomycetes) patógenos de insectos de la República Argentina. Bol. Soc. Argent. Bot. 2007, 42, 33–37. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.Z.; Huang, B.; Fan, M.Z. New species, new record, new combinations and emendation of entomophthoralean fungi pathogenic on dipteran insects. Mycosystema 1997, 16, 91–96. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, C.S.; Hong, B. Zoophthora radicans infecting larvae of Cnaphalocrocis medinalis and its epizootic. Mycosystema 2012, 31, 322–330. [Google Scholar]

- Hannam, J.J.; Steinkraus, D.C. The natural occurrence of Pandora heteropterae (Zygomycetes: Entomophthorales) infecting Lygus lineolaris (Hemiptera: Miridae). J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2010, 103, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milner, R.J.; Bourne, J. Influence of temperature and duration of leaf wetness on infection of Acyrthosiphon kondoi with Erynia neoaphidis. Ann. Appl. Biol. 1983, 102, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, I.M.; Lowe, A.D.; Given, B.B. New record of aphid hosts of Entomophthora aphidis and Entomophthora planchoniana in New Zealand. N. Z. J. Zool. 1976, 3, 111–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milner, R.J.; Teakle, R.E.; Lutton, G.G.; Dare, F.M. Pathogens (Phycomycetes: Entomophthoraceae) of the blue-green aphid Acyrthosiphon kondoi Shinji and other aphids in Australia. Aust. J. Bot. 1980, 28, 601–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, Y.; Mogami, K.; Aoki, J. Ultrastructural studies on the hyphal growth of Erynia neoaphidis in the green peach aphid, Myzus persicae. Trans. Mycol. Soc. Jpn. 1984, 25, 425–434. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, W.H.; Wang, W.M. Investigation and identification of several aphid entomophthoralean fungi in Shandong Province. Microbiology 1988, 15, 155–159. [Google Scholar]

- Papierok, B. On the occurrence of Entomophthorales (Zygomycetes) in Finland. I. Species attacking aphids (Homoptera, Aphididae). Ann. Entomol. Fenn. 1989, 55, 63–69. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, M.-G.; Johnson, J.B.; Kish, L.P. Survey of Entomopathogenic Fungi Naturally Infecting Cereal Aphids (Homoptera: Aphididae) of Irrigated Grain Crops in Southwestern Idaho. Environ. Entomol. 1990, 19, 1534–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, M.G.; Nowierski, R.M.; Scharen, A.L.; Sands, D.C. Entomopathogenic fungi (Zygomycotina: Entomophthorales) infecting cereal aphids (Homoptera: Aphididae) in Montana. Pan-Pac. Entomol. 1991, 7, 55–64. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Z.; Nordin, G.L.; Brown, G.C.; Jackson, D.M. Studies on Pandora neoaphidis (Entomophthorales: Entomophthoraceae) Infectious to the Red Morph of Tobacco Aphid (Homoptera: Aphididae). Environ. Entomol. 1995, 24, 962–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Tzean, S.S.; Hsieh, L.S.; Wu, W.J. Atlas of Entomopathogenic Fungi from Taiwan; Council of Agriculture, Executive Yuan: Taiwan, China, 1997.

- Yoon, C.-S.; Sung, G.-H.; Choi, B.-R.; Yoo, J.-K.; Lee, J.-O. The Aphid-attacking Fungus Pandora neoaphidis; the First Observation and its Host Range in Korea. Korean J. Mycol. 1998, 26, 407–410. [Google Scholar]

- Hatting, J.L.; Humber, R.A.; Poprawski, T.J.; Miller, R.M. A Survey of Fungal Pathogens of Aphids from South Africa, with Special Reference to Cereal Aphids. Biol. Control 1999, 16, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatting, J.L.; Poprawski, T.J.; Miller, R.M. Prevalences of fungal pathogens and other natural enemies of cereal aphids (Homoptera:Aphididae) in wheat under dryland and irrigated conditions in South Africa. BioControl 2000, 45, 179–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, C.; Eilenberg, J.; Harding, S.; Oddsdottir, E.; Halldórsson, G. Geographical distribution and host range of entomophthorales infecting the green spruce aphid Elatobium abietinum Walker in Iceland. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2001, 78, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nielsen, C.; Sommer, C.; Eilenberg, J.; Hansen, K.S.; Humber, R.A. Characterization of aphid pathogenic species in the genus Pandora by PCR techniques and digital image analysis. Mycologia 2001, 93, 864–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voronina, E.G.; Lednev, G.R.; Mukamolova, T.J. Entomophthoralean fungi. In Pathogens of Insects: Structural and Functional Aspects; Glupov, V.V., Ed.; Kruglyi God: Moscow, Russia, 2001; pp. 271–351. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Sheng, C.-F. Occurrence and distribution of entomophthoralean fungi infecting aphids in mainland China. Biocontrol Sci. Technol. 2007, 17, 433–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scorsetti, A.C.; Humber, R.A.; García, J.J.; Lastra, C.C.L. Natural occurrence of entomopathogenic fungi (Zygomycetes: Entomophthorales) of aphid (Hemiptera: Aphididae) pests of horticultural crops in Argentina. BioControl 2007, 52, 641–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scorsetti, A.C.; Maciá, A.; Steinkraus, D.C.; López Lastra, C.C. Prevalence of Pandora neoaphidis (Zygomycetes: Entomophthorales) infecting Nasonovia ribisnigri (Hemiptera: Aphididae) on lettuce crops in Argentina. Biol. Control 2010, 52, 46–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzugaray, R.; Ribeiro, A.; Silva, H.; Stewart, S.; Castiglioni, E.; Bartaburu, S.; Martínez, J.J. Prospección de agentes de mortalidad natural de áfidos en leguminosas forrajeras en Uruguay. Agrociencia 2010, 14, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moubasher, A.; Abdel-Rahman, M.; Abdel-Mallek, A.; Hammam, G. Biodiversity of entomopathogenic fungi infecting wheat and cabbage aphids in Assiut, Egypt. J. Basic. Appl. Mycol. 2010, 1, 53–60. [Google Scholar]

- Ben Fekih, I.; Boukhris-Bouhachem, S.; Bechir Allagui, M.; Bruun Jensen, A.; Eilenberg, J. First survey on ecological host range of aphid pathogenic fungi (Phylum Entomophthoromycota) in Tunisia. Ann. Soc. Entomol. Fr. 2015, 51, 140–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Fekih, I.; Jensen, A.B.; Boukhris-Bouhachem, S.; Pozsgai, G.; Rezgui, S.; Rensing, C.; Eilenberg, J. Virulence of Two Entomophthoralean Fungi, Pandora neoaphidis and Entomophthora planchoniana, to Their Conspecific (Sitobion avenae) and Heterospecific (Rhopalosiphum padi) Aphid Hosts. Insects 2019, 10, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, S. Entomophthorales attacking aphids with a description of two new species. Sydowia 2006, 58, 38–74. [Google Scholar]

- Toledo, A.V.; Humber, R.A.; Lastra, C.C.L. First and southernmost records of Hirsutella (Ascomycota: Hypocreales) and Pandora (Zygomycota: Entomophthorales) species infecting Dermaptera and Psocodea. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2008, 97, 193–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steenberg, T.; Langer, V.; Esbjerg, P. Entomopathogenic fungi in predatory beetles (Col.: Carabidae and Staphylinidae) from agricultural fields. Entomophaga 1995, 40, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gres, Y.A.; Koval, E.Z. A new species Entomorphthora terrestris sp. nova affecting the sugar-beet root aphid. Mikrobiol. Zhurnal 1982, 44, 64–69. [Google Scholar]

- Barta, M.; Cagáň, L. Pandora uroleuconii sp. nov. (Zygomycetes: Entomophthoraceae), a new pathogen of aphids. Mycotaxon 2003, 88, 79–86. [Google Scholar]

- Eilenberg, J.; Michelsen, V.; Humber, R. Strongwellsea tigrinae and Strongwellsea acerosa (Entomophthorales: Entomophthoraceae), two new species infecting dipteran hosts from the genus Coenosia (Muscidae). J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2020, 175, 107444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batko, A.; Weiser, J. On the taxonomic position of the fungus discovered by Strong, Wells, and Apple: Strongwellsea castrans gen. et sp. nov. (Phycomycetes; Entomophthoraceae). J. Invertebr. Pathol. 1965, 7, 455–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, S. Arthropod-pathogenic Entomophthorales of Switzerland. I. Conidiobolus, Entomophaga and Entomophthora. Sydowia 1987, 40, 122–167. [Google Scholar]

- Eilenberg, J.; Michelsen, V.; Jensen, A.B.; Humber, R.A. Strongwellsea crypta (Entomophthorales: Entomophthoraceae), a new species infecting Botanophila fugax (Diptera: Anthomyiidae). J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2021, 186, 107673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eilenberg, J.; Michelsen, V.; Jensen, A.B.; Humber, R.A. Strongwellsea selandia and Strongwellsea gefion (Entomophthorales: Entomophthoraceae), two new species infecting adult flies from genus Helina (Diptera: Muscidae). J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2022, 193, 107797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Humber, R.A. The systematics of the genus Strongwellsea (Zygomycetes: Entomophthorales). Mycologia 1976, 68, 1042–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eilenberg, J.; Michelsen, V. Natural host range and prevalence of the genus Strongwellsea (Zygomycota: Entomophthorales) in Denmark. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 1990, 73, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eilenberg, J.; Jensen, A.B. Strong host specialization in fungus genus Strongwellsea (Entomophthorales). J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2018, 157, 112–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turian, G. Entomo-mycoses dans la région de Genéve. Entomol. Ges. 1957, 30, 93–98. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.Z. Erynia anhuensis, a new pathogen of aphids. Acta Mycol. Sin. 1986, 5, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, R.X.; Lin, G.X.; Guan, X. A list of Fujian pathogenic microbes on pest. J. Fujian Agric. Coll. 1986, 15, 300–310. [Google Scholar]

- Voronina, E.G.; Mukamolova, T.J. Diagnostics of Entomophthoroses of Harmful Insects; OOO Innovation Center VIZR: Saint Petersburg, Russia, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.Z.; Chen, Z.A.; Lu, C.R.; Hong, H.Z. Some entomophthoralean species in Shennongjia. In Fungi and Lichens of Shennongjia; Mycological and Lichenological Expedition to Shennongjia; Academia Sinica, Ed.; World Publishing Corporation: Beijing, China, 1989; pp. 79–83. [Google Scholar]

- MacLeod, D.M.; Tyrrell, D.; Soper, R.S. Entomophthora canadensis n. sp., a fungus pathogenic on the woolly pine needle aphid, Schizolachnus piniradiatae. Can. J. Bot. 1979, 57, 2663–2672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aruta, C.; Carvillo, R. Identificación de hongos del orden Entomophthorales en Chile. III. Agro Sur 1989, 17, 10–14. [Google Scholar]

- Hajek, A.E.; Gryganskyi, A.; Bittner, T.; Liebherr, J.K.; Liebherr, J.H.; Jensen, A.B.; Moulton, J.K.; Humber, R.A. Phylogenetic placement of two species known only from resting spores: Zoophthora independentia sp. nov. and Z. porteri comb nov. (Entomophthorales: Entomophthoraceae). J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2016, 140, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keller, S. Two new species of the genus Zoophthora Batko (Zygomycetes, Entomophthoraceae): Z. lanceolata and Z. crassitunicata. Sydowia 1980, 33, 167–173. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, C.; Hajek, A.E. Control of Invasive Soybean Aphid, Aphis glycines (Hemiptera: Aphididae), Populations by Existing Natural Enemies in New York State, with Emphasis on Entomopathogenic Fungi. Environ. Entomol. 2005, 34, 1036–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.L.; Huang, Z.H.; Chen, C.H. A new Zoophthora occidentalis pathogen of Myzus persicae in China. Fujian J. Agric. Sci. 2014, 29, 673–677. [Google Scholar]

- Glare, T.R.; Milner, R.J.; Chilvers, G.A. The effect of environmental factors on the production, discharge, and germination of primary conidia of Zoophthora phalloides Batko. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 1986, 48, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uziel, A.; Kenneth, R.G. Survival of primary conidia and capilliconidia at different humidities in Erynia (subgen. Zoophthora) spp. and in Neozygites fresenii (Zygomycotina: Entomophthorales), with special emphasis on Erynia radicans. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 1991, 58, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manfrino, R.G.; Castrillo, L.A.; Lastra, C.C.L.; Toledo, A.V.; Ferrari, W.; Jensen, A.B. Morphological and Molecular Characterization of Entomophthorales (Entomophthoromycota: Entomophthoromycotina) from Argentina. Acta Mycol. 2020, 55, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajek, A.E.; Hodge, K.T.; Liebherr, J.K.; Day, W.H.; Vandenberg, J.D. Use of RAPD analysis to trace the origin of the weevil pathogen Zoophthora phytonomi in North America. Mycol. Res. 1996, 100, 349–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimazu, M. Resting Spore Formation of Entmophthora sphaerosperma Fresenius (Entomophthorales: Entmophthoraceae) in the Brown Planthopper, Nilaparvata lugens (Stal) (Hemiptera: Delphacidae). Appl. Entomol. Zool. 1979, 14, 383–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milner, R.J.; Mahon, R.J. Strain variation in Zoophthora radicans, a pathogen on a variety of insect hosts in Australia. Aust. J. Entomol. 1985, 24, 195–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Zheng, B.N.; Zhu, H.Q. Isolation, identification and biological determination of Erynia radicans. Pract. For. Technol. 1988, 1998, 16–18. [Google Scholar]

- Galaini-Wraight, S.; Wraight, S.P.; Carruthers, R.I.; Magalhães, B.P.; Roberts, D.W. Description of a Zoophthora radicans (Zygomycetes: Entomophthoraceae) epizootic in a population of Empoasca kraemeri (Homoptera: Cicadellidae) on beans in central Brazil. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 1991, 58, 311–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzugaray, R.; Stewart, S.; Zebrino, M.S. Epizootia por hongos sobre Epinotia aporema (Wals) (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae) en Uruguay. Bol. Soc. Zool. Urug. 1992, 7, 79. [Google Scholar]

- Alzugaray, R.; Zerbino, M.S.; Stewart, S.; Ribeiro, A.; Eilenberg, J. Epizootiologia de hongos Entomophthorales. Uso de Zoophthora radicans (Brefeld) Batko (Zygomicotina: Entomophthorales) para el control de Epinotia aporema (Wals.) (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae) en Uruguay. Rev. Soc. Entomol. Argent. 1999, 58, 307–311. [Google Scholar]

- Nagahama, T.; Sato, H.; Shimazu, M.; Sugiyama, J. Phylogenetic Divergence of the Entomophthoralean Fungi: Evidence from Nuclear 18S Ribosomal RNA Gene Sequences. Mycologia 1995, 87, 203–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite, L.G.; Alves, S.B.; Wraight, S.P.; Galaini-Wraight, S.; Roberts, D.W. Habilidade de infecção de isolados de Zoophthora radicans sobre Empoasca kraemeri. Sci. Agríc 1996, 53, 152–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzmán-Franco, A.W.; Atkins, S.D.; Alderson, P.G.; Pell, J.K. Development of species-specific diagnostic primers for Zoophthora radicans and Pandora blunckii; two co-occurring fungal pathogens of the diamondback moth, Plutella xylostella. Mycol. Res. 2008, 112 Pt 10, 1227–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzmán-Franco, A.W.; Clark, S.J.; Alderson, P.G.; Pell, J.K. Competition and co-existence of Zoophthora radicans and Pandora blunckii, two co-occurring fungal pathogens of the diamondback moth, Plutella xylostella. Mycol. Res. 2009, 113 Pt 11, 1312–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, L.F.A.; Leite, L.G.; Oliveira, D.G.P. de Primeiro Registro de Zoophthora radicans (Entomophthorales: Entomophthoraceae) em Adultos da Ampola-da-Erva-Mate, Gyropsylla spegazziniana Lizer & Trelles (Hemiptera: Psyllidae), no Brasil. Neotrop. Entomol. 2009, 38, 697–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mascarin, G.M.; da Duarte, V.S.; Brandão, M.M.; Delalibera, Í. Natural occurrence of Zoophthora radicans (Entomophthorales: Entomophthoraceae) on Thaumastocoris peregrinus (Heteroptera: Thaumastocoridae), an invasive pest recently found in Brazil. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2012, 110, 401–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manfrino, R.G.; Zumoffen, L.; Salto, C.E.; López Lastra, C.C. Potential plant–aphid–fungal associations aiding conservation biological control of cereal aphids in Argentina. Int. J. Pest. Manag. 2013, 59, 314–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manfrino, R.G.; Gutiérrez, A.C.; Steinkraus, D.C.; Salto, C.E.; López Lastra, C.C. Prevalence of entomophthoralean fungi (Entomophthoromycota) of aphids (Hemiptera: Aphididae) on solanaceous crops in Argentina. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2014, 121, 21–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manfrino, R.; Hatting, J.; Humber, R.; Salto, C.; Lastra, C. Natural occurrence of entomophthoroid fungi (Entomophthoromycota) of aphids (Hemiptera: Aphididae) on cereal crops in Argentina. Ann. Appl. Biol. 2014, 164, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, A.; Silva, H.; Castiglioni, E.; Bartaburu, S.; Martínez, J.J. Control natural de Crocidosema (Epinotia) aporema (Walsingham) (Lepidoptera:Tortricidae) por parasitoides y hongos entomopatógenos en Lotus corniculatus y Glycine max. Agrociencia 2015, 19, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.; Kim, J.; Seo, K.; Moon, Y.; Lee, G.; Lee, C.; Kim, J.; Kim, J. Occurrence of the Entomopathogenic Fungus Zoophthora radicans (Entomophthorales: Entomophthoraceae) in Jeollabuk-do, Korea. Korean J. Appl. Entomol. 2017, 56, 195–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajek, A.E.; Liebherr, J.K.; Keller, S. The first New World records of Zoophthora rhagonycharum (Zoopagomycota, Entomophthorales) infecting Rhagonycha spp. (Coleoptera, Cantharidae). Check List. 2024, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Gryganskyi, A.P.; Mullens, B.A.; Gajdeczka, M.T.; Rehner, S.A.; Vilgalys, R.; Hajek, A.E. Hijacked: Co-option of host behavior by entomophthoralean fungi. PLoS Pathog. 2017, 13, e1006274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, M.-G.; Chen, C.; Shang, S.-W.; Ying, S.-H.; Shen, Z.-C.; Chen, X.-X. Aphid dispersal flight disseminates fungal pathogens and parasitoids as natural control agents of aphids. Ecol. Entomol. 2007, 32, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajek, A.E.; Papierok, B.; Eilenberg, J. Methods for study of the Entomophthorales. In Manual of Techniques in Invertebrate Pathology, 2nd ed.; Lacey, L.A., Ed.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2012; pp. 285–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller-Kögler, E. Zur Isolierung und Kultur Insektenpathogener Entomophthoraceen. Entomophaga 1959, 3, 261–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muskat, L.C.; Kerkhoff, Y.; Humbert, P.; Nattkemper, T.W.; Eilenberg, J.; Patel, A.V. Image analysis-based quantification of fungal sporulation by automatic conidia counting and gray value correlation. MethodsX 2021, 8, 101218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muskat, L.C.; Görg, L.M.; Humbert, P.; Gross, J.; Eilenberg, J.; Patel, A.V. Encapsulation of the psyllid-pathogenic fungus Pandora sp. nov. inedit. and experimental infection of target insects. Pest. Manag. Sci. 2022, 78, 991–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajek, A.E.; Humber, R.A.; Griggs, M.H. Decline in virulence of Entomophaga maimaiga (Zygomycetes: Entomophthorales) with repeated in vitro subculture. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 1990, 56, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, R.B.; Faria, M.; Souza, D.A.; Sosa-Gómez, D.R. Potential Impact of Chemical Fungicides on the Efficacy of Metarhizium rileyi and the Occurrence of Pandora gammae on Caterpillars in Soybean Crops. Microb. Ecol. 2023, 86, 647–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scorsetti, A.C.; Jensen, A.B.; López Lastra, C.; Humber, R.A. First report of Pandora neoaphidis resting spore formation in vivo in aphid hosts. Fungal Biol. 2012, 116, 196–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tymon, A.M.; Shah, P.A.; Pell, J.K. PCR-based molecular discrimination of Pandora neoaphidis isolates from related entomopathogenic fungi and development of species-specific diagnostic primers. Mycol. Res. 2004, 108, 419–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoch, C.L.; Robbertse, B.; Robert, V.; Vu, D.; Cardinali, G.; Irinyi, L.; Meyer, W.; Nilsson, R.H.; Hughes, K.; Miller, A.N.; et al. Finding needles in haystacks: Linking scientific names, reference specimens and molecular data for Fungi. Database 2014, 2014, bau061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grell, M.N.; Jensen, A.B.; Olsen, P.B.; Eilenberg, J.; Lange, L. Secretome of fungus-infected aphids documents high pathogen activity and weak host response. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2011, 48, 343–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fournier, A.; Enkerli, J.; Keller, S.; Widmer, F. A PCR-based tool for the cultivation-independent monitoring of Pandora neoaphidis. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2008, 99, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fournier, A.; Widmer, F.; Enkerli, J. Assessing winter-survival of Pandora neoaphidis in soil with bioassays and molecular approaches. Biol. Control 2010, 54, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.; Yun, S.H.; Hodge, K.T.; Humber, R.A.; Krasnoff, S.B.; Turgeon, G.B.; Yoder, O.C.; Gibson, D.M. Polyketide synthase genes in insect- and nematode-associated fungi. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2001, 56, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fournier, A.; Widmer, F.; Enkerli, J. Development of a single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) assay for genotyping of Pandora neoaphidis. Fungal Biol. 2010, 114, 498–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, M.-J.; Xie, T.-N.; Chen, C. Effects of different wavelength light on the sporulation ability of Pandora neoaphidis and the cloning and expression analysis of fungal blue-light receptor gene. Mycosystema 2019, 38, 372–380. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Chen, C.; Xie, T.; Ye, S. Identification and validation of reference genes for qRT-PCR studies of the obligate aphid pathogenic fungus Pandora neoaphidis during different developmental stages. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0179930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Baldwin, D.; Kindrachuk, C.; Hegedus, D.D. Comparative EST analysis of a Zoophthora radicans isolate derived from Pieris brassicae and an isogenic strain adapted to Plutella xylostella. Microbiology 2009, 155, 174–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Fasoyin, O.E.; Molnár, I.; Xu, Y. Secondary metabolites from hypocrealean entomopathogenic fungi: Novel bioactive compounds. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2020, 37, 1181–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabima, J.F.; Trautman, I.A.; Chang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Mondo, S.; Kuo, A.; Salamov, A.; Grigoriev, I.V.; Stajich, J.E.; Spatafora, J.W. Phylogenomic analyses of non-Dikarya fungi supports horizontal gene transfer driving diversification of secondary metabolism in the amphibian gastrointestinal symbiont, Basidiobolus. G3 Genes|Genomes|Genet. 2020, 10, 3417–3433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sowjanya Sree, K.; Padmaja, V.; Murthy, Y.L.N. Insecticidal activity of destruxin, a mycotoxin from Metarhizium anisopliae (Hypocreales), against Spodoptera litura (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) larval stages. Pest. Manag. Sci. 2008, 64, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, H.; Wang, F.; Liu, C.; Reddy, G.V.P.; Li, H.; Li, Z.; Sun, Y.; Zhao, Z. Discovery of a new highly pathogenic toxin involved in insect sepsis. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e01422-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amses, K.R.; Simmons, D.R.; Longcore, J.E.; Mondo, S.J.; Seto, K.; Jerônimo, G.H.; Bonds, A.E.; Quandt, C.A.; Davis, W.J.; Chang, Y.; et al. Diploid-dominant life cycles characterize the early evolution of Fungi. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2116841119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bushley, K.E.; Raja, R.; Jaiswal, P.; Cumbie, J.S.; Nonogaki, M.; Boyd, A.E.; Owensby, C.A.; Knaus, B.J.; Elser, J.; Miller, D.; et al. The Genome of Tolypocladium inflatum: Evolution, Organization, and Expression of the Cyclosporin Biosynthetic Gene Cluster. PLoS Genet. 2013, 9, e1003496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Bekker, C.; Ohm, R.A.; Evans, H.C.; Brachmann, A.; Hughes, D.P. Ant-infecting Ophiocordyceps genomes reveal a high diversity of potential behavioral manipulation genes and a possible major role for enterotoxins. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 12508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seto, K.; Simmons, D.R.; Quandt, C.A.; Frenken, T.; Dirks, A.C.; Clemons, R.A.; McKindles, K.M.; McKay, R.M.L.; James, T.Y. A combined microscopy and single-cell sequencing approach reveals the ecology, morphology, and phylogeny of uncultured lineages of zoosporic fungi. mBio 2023, 14, e01313-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigoriev, I.V.; Nordberg, H.; Shabalov, I.; Aerts, A.; Cantor, M.; Goodstein, D.; Kuo, A.; Minovitsky, S.; Nikitin, R.; Ohm, R.A.; et al. The Genome Portal of the Department of Energy Joint Genome Institute. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, D26–D32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gryganskyi, A.P.; Golan, J.; Muszewska, A.; Idnurm, A.; Dolatabadi, S.; Mondo, S.J.; Kutovenko, V.B.; Kutovenko, V.O.; Gajdeczka, M.T.; Anishchenko, I.M.; et al. Sequencing the Genomes of the First Terrestrial Fungal Lineages: What Have We Learned? Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grigoriev, I.V.; Nikitin, R.; Haridas, S.; Kuo, A.; Ohm, R.; Otillar, R.; Riley, R.; Salamov, A.; Zhao, X.; Korzeniewski, F.; et al. MycoCosm portal: Gearing up for 1000 fungal genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, D699–D704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quesada-Moraga, E.; González-Mas, N.; Yousef-Yousef, M.; Garrido-Jurado, I.; Fernández-Bravo, M. Key role of environmental competence in successful use of entomopathogenic fungi in microbial pest control. J. Pest. Sci. 2023, 97, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).