The Role of Rumen Microbiota and Its Metabolites in Subacute Ruminal Acidosis (SARA)-Induced Inflammatory Diseases of Ruminants

Abstract

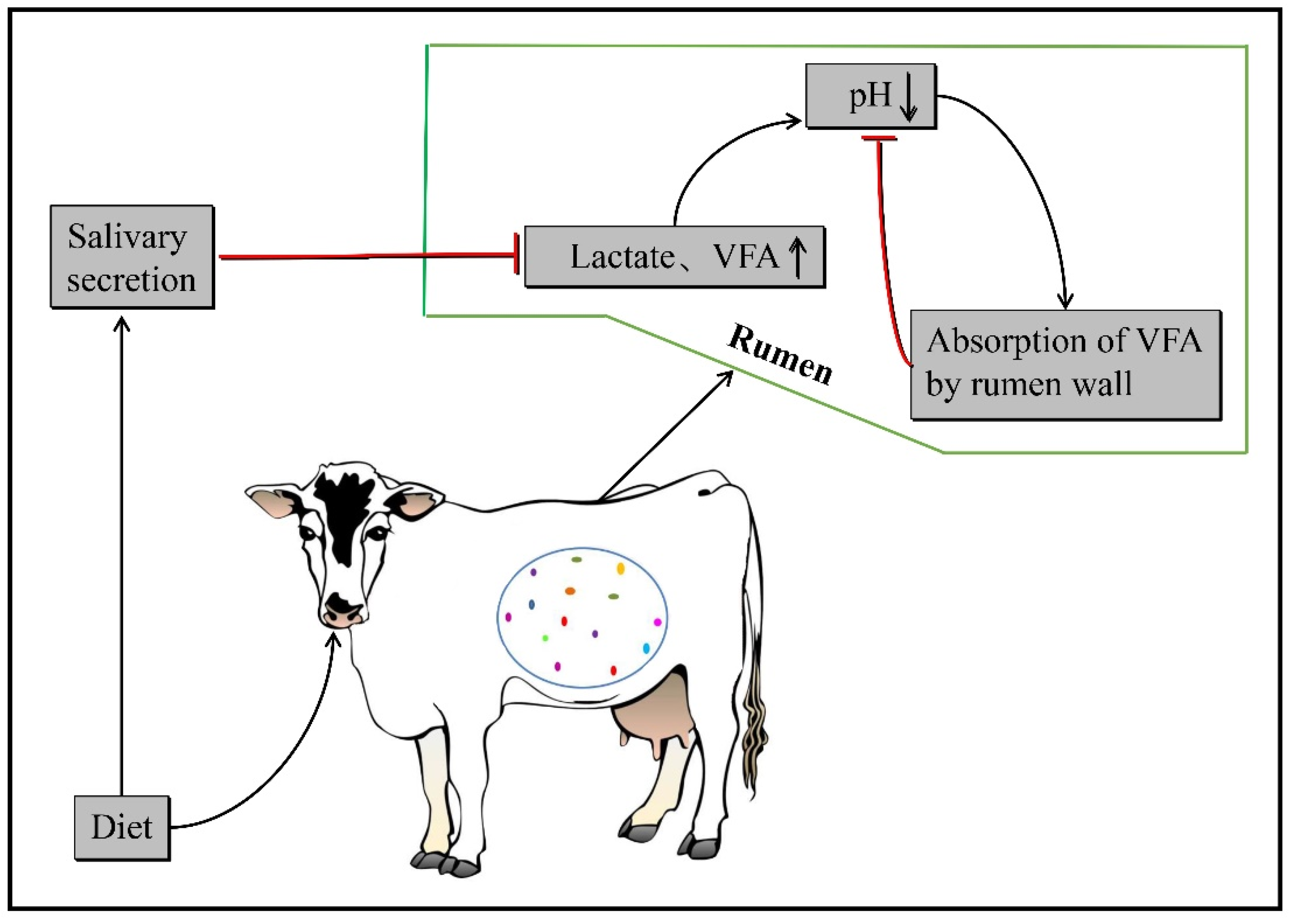

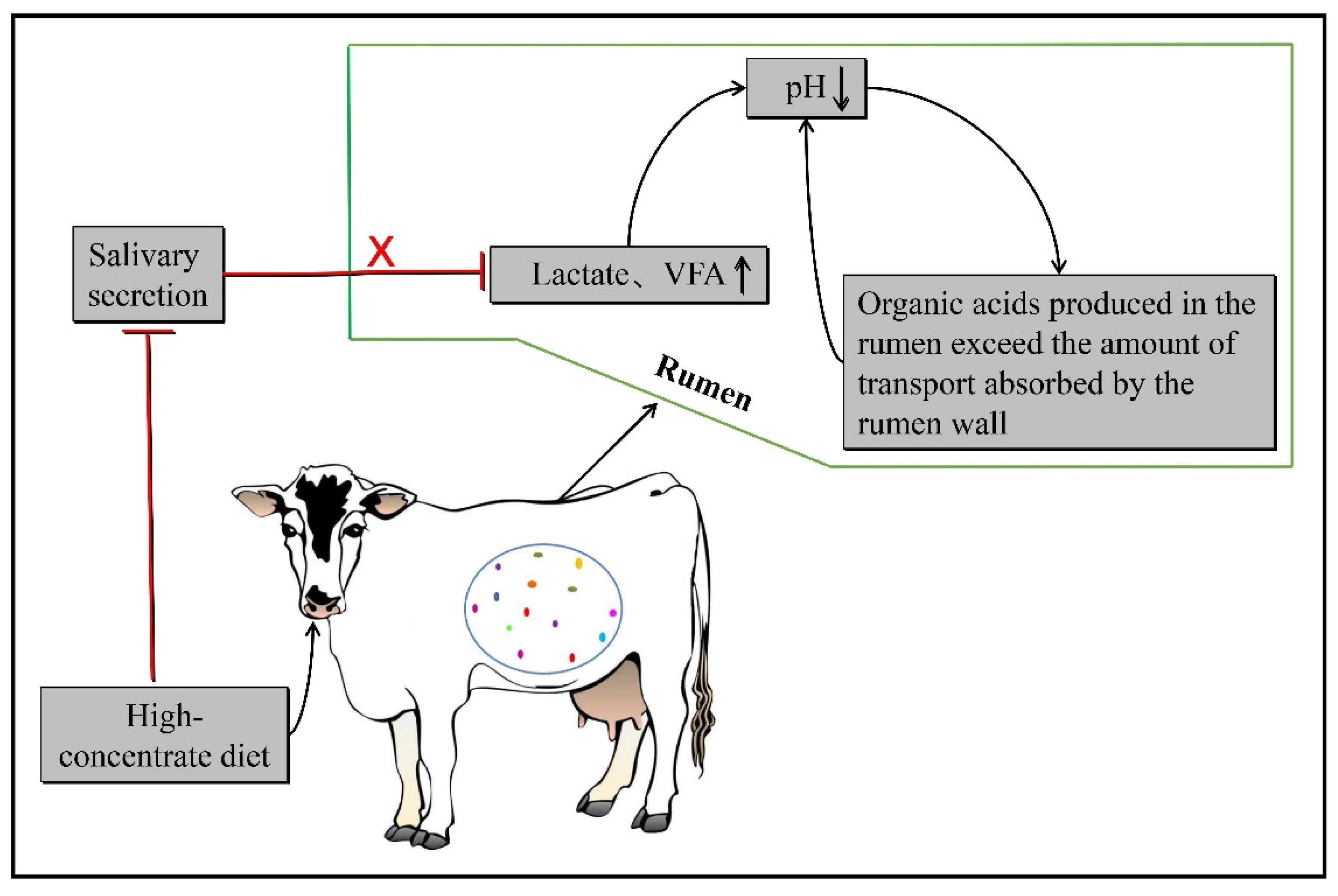

:1. The Pathogenesis of Subacute Ruminal Acidosis

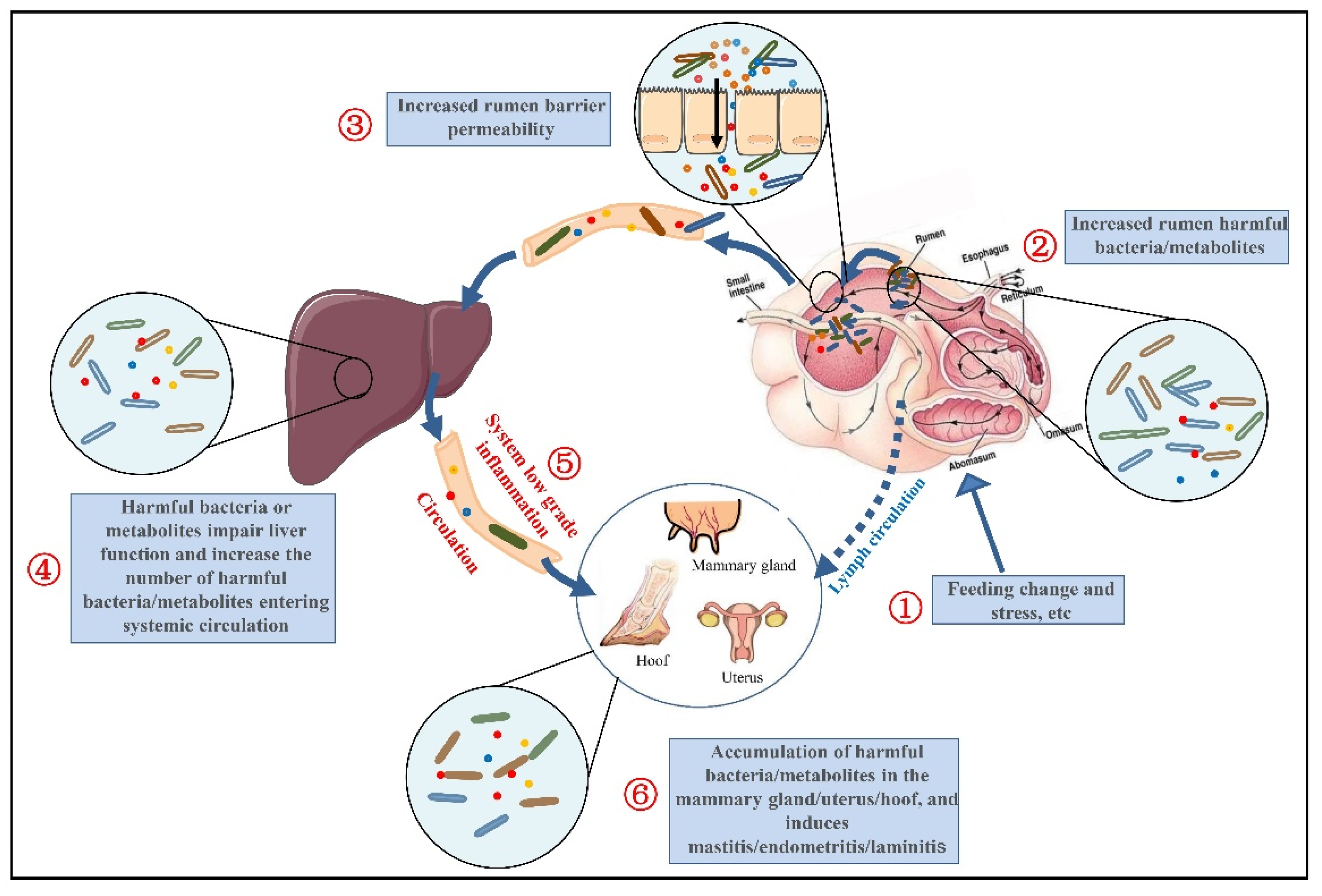

2. Relationship between SARA and Its Related Inflammatory Diseases in Ruminants

2.1. SARA and Liver Disorders

2.2. SARA and Mastitis

2.3. SARA and Endometritis

2.4. SARA and Laminitis

3. Low-Grade Inflammation in SARA

4. The Mechanism of SARA-Mediated IGL and Related Inflammatory Diseases

4.1. Ruminal Microbiota Dysbiosis in SARA

4.2. The Destruction of the Rumen Barrier in SARA

4.3. Liver Dysfunction in SARA

4.4. Ruminal Microbiota Dysbiosis Leads to the Release of Metabolites into the Blood and Tissues, Causing Inflammation and Related Diseases

4.4.1. LPS

4.4.2. Histamine

4.4.3. Other Metabolites

4.5. Ruminal Microbiota Dysbiosis Leads to Bacterial Translocation, Causing Inflammation and Related Diseases

4.6. Ruminal Microbiota Dysbiosis Facilitates Susceptibility to Pathogens

5. Regulating the Rumen Microbiota to Prevent SARA and Related Diseases in Dairy Cows

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abdela, N. Sub-acute ruminal acidosis (SARA) and its consequence in dairy cattle: A review of past and recent research at global prospective. Achiev. Life Sci. 2016, 10, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hu, X.; Li, S.; Mu, R.; Guo, J.; Zhao, C.; Cao, Y.; Zhang, N.; Fu, Y. The Rumen Microbiota Contributes to the Development of Mastitis in Dairy Cows. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022, 10, e0251221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garrett, E.F.; Pereira, M.N.; Nordlund, K.V.; Armentano, L.E.; Goodger, W.J.; Oetzel, G.R. Diagnostic methods for the detection of subacute ruminal acidosis in dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 1999, 82, 1170–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plaizier, J.C. Replacing chopped alfalfa hay with alfalfa silage in barley grain and alfalfa-based total mixed rations for lactating dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2004, 87, 2495–2505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gozho, G.N.; Plaizier, J.C.; Krause, D.O.; Kennedy, A.D.; Wittenberg, K.M. Subacute ruminal acidosis induces ruminal lipopolysaccharide endotoxin release and triggers an inflammatory response. J. Dairy Sci. 2005, 88, 1399–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Devries, T.J.; Dohme, F.; Beauchemin, K.A. Repeated ruminal acidosis challenges in lactating dairy cows at high and low risk for developing acidosis: Feed sorting. J. Dairy Sci. 2008, 91, 3958–3967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penner, G.B. Mechanisms of volatile fatty acid absorption and metabolism and maintenance of a stable rumen environment. In Proceedings of the 25th Florida Ruminant Nutrition Symposium, Gainesville, FL, USA, 20 January 2014; pp. 92–104. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, F.G.; Lin, X.Y.; Yan, Z.G.; Hu, Z.Y.; Liu, G.M.; Sun, Y.D.; Liu, X.W.; Wang, Z.H. Effect of dietary roughage level on chewing activity, ruminal pH, and saliva secretion in lactating Holstein cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2017, 100, 2660–2671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kleen, J.L.; Hooijer, G.A.; Rehage, J.; Noordhuizen, J.P. Subacute ruminal acidosis (SARA): A review. J. Vet. Med. A Physiol. Pathol. Clin. Med. 2003, 50, 406–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, K.M.; Oetzel, G.R. Understanding and preventing subacute ruminal acidosis in dairy herds: A review. Anim. Feed. Sci. Technol. 2006, 126, 215–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Su, X.; Li, J.; Yang, Y.; Wang, P.; Yan, F.; Yao, J.; Wu, S. Real-time monitoring of ruminal microbiota reveals their roles in dairy goats during subacute ruminal acidosis. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes 2021, 7, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, S.; Zhang, R.; Wang, D.; Zhu, W. The diversity of the fecal bacterial community and its relationship with the concentration of volatile fatty acids in the feces during subacute rumen acidosis in dairy cows. BMC Vet. Res. 2012, 8, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhang, T.; Mu, Y.; Zhang, R.; Xue, Y.; Guo, C.; Qi, W.; Zhang, J.; Mao, S. Responsive changes of rumen microbiome and metabolome in dairy cows with different susceptibility to subacute ruminal acidosis. Anim. Nutr. 2022, 8, 331–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsuchiya, Y.; Ozai, R.; Sugino, T.; Kawashima, K.; Kushibiki, S.; Kim, Y.H.; Sato, S. Changes in peripheral blood oxidative stress markers and hepatic gene expression related to oxidative stress in Holstein cows with and without subacute ruminal acidosis during the periparturient period. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2020, 82, 1529–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daros, R.R.; Hotzel, M.J.; Bran, J.A.; LeBlanc, S.J.; von Keyserlingk, M.A.G. Prevalence and risk factors for transition period diseases in grazing dairy cows in Brazil. Prev. Vet. Med. 2017, 145, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vergara, C.F.; Dopfer, D.; Cook, N.B.; Nordlund, K.V.; McArt, J.A.; Nydam, D.V.; Oetzel, G.R. Risk factors for postpartum problems in dairy cows: Explanatory and predictive modeling. J. Dairy Sci. 2014, 97, 4127–4140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhang, F.; Nan, X.; Wang, H.; Zhao, Y.; Guo, Y.; Xiong, B. Effects of Propylene Glycol on Negative Energy Balance of Postpartum Dairy Cows. Animals 2020, 10, 1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plaizier, J.C.; Krause, D.O.; Gozho, G.N.; McBride, B.W. Subacute ruminal acidosis in dairy cows: The physiological causes, incidence and consequences. Vet. J. 2008, 176, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakao, A.; Taki, S.; Yasui, M.; Kimura, Y.; Nonami, T.; Harada, A.; Takagi, H. The fate of intravenously injected endotoxin in normal rats and in rats with liver failure. Hepatology 1994, 19, 1251–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vels, L.; Rontved, C.M.; Bjerring, M.; Ingvartsen, K.L. Cytokine and acute phase protein gene expression in repeated liver biopsies of dairy cows with a lipopolysaccharide-induced mastitis. J. Dairy Sci. 2009, 92, 922–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamesch, K.; Borkham-Kamphorst, E.; Strnad, P.; Weiskirchen, R. Lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammatory liver injury in mice. Lab. Anim. 2015, 49 (Suppl. 1), 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abaker, J.A.; Xu, T.L.; Jin, D.; Chang, G.J.; Zhang, K.; Shen, X.Z. Lipopolysaccharide derived from the digestive tract provokes oxidative stress in the liver of dairy cows fed a high-grain diet. J. Dairy Sci. 2017, 100, 666–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, J.; Chang, G.; Zhang, K.; Xu, L.; Jin, D.; Bilal, M.S.; Shen, X. Rumen-derived lipopolysaccharide provoked inflammatory injury in the liver of dairy cows fed a high-concentrate diet. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 46769–46780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chang, G.; Zhuang, S.; Seyfert, H.M.; Zhang, K.; Xu, T.; Jin, D.; Guo, J.; Shen, X. Hepatic TLR4 signaling is activated by LPS from digestive tract during SARA, and epigenetic mechanisms contribute to enforced TLR4 expression. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 38578–38590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jia, Y.Y.; Wang, S.Q.; Ni, Y.D.; Zhang, Y.S.; Zhuang, S.; Shen, X.Z. High concentrate-induced subacute ruminal acidosis (SARA) increases plasma acute phase proteins (APPs) and cortisol in goats. Animal 2014, 8, 1433–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, T.L.; Seyfert, H.M.; Shen, X.Z. Epigenetic mechanisms contribute to decrease stearoyl-CoA desaturase 1 expression in the liver of dairy cows after prolonged feeding of high-concentrate diet. J. Dairy Sci. 2018, 101, 2506–2518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sato, S.; Ikeda, A.; Tsuchiya, Y.; Ikuta, K.; Murayama, I.; Kanehira, M.; Okada, K.; Mizuguchi, H. Diagnosis of subacute ruminal acidosis (SARA) by continuous reticular pH measurements in cows. Vet. Res. Commun. 2012, 36, 201–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, K.; Chang, G.; Xu, T.; Xu, L.; Guo, J.; Jin, D.; Shen, X. Lipopolysaccharide derived from the digestive tract activates inflammatory gene expression and inhibits casein synthesis in the mammary glands of lactating dairy cows. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 9652–9665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wellnitz, O.; Bruckmaier, R.M. Invited review: The role of the blood-milk barrier and its manipulation for the efficacy of the mammary immune response and milk production. J. Dairy Sci. 2021, 104, 6376–6388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, J.Y.; Groer, M.; Dutra, S.V.O.; Sarkar, A.; McSkimming, D.I. Gut Microbiota and Immune System Interactions. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quigley, E.M. Gut bacteria in health and disease. Gastroente. Erol. Hepatol. 2013, 9, 560–569. [Google Scholar]

- Bilal, M.S.; Abaker, J.A.; Ul Aabdin, Z.; Xu, T.; Dai, H.; Zhang, K.; Liu, X.; Shen, X. Lipopolysaccharide derived from the digestive tract triggers an inflammatory response in the uterus of mid-lactating dairy cows during SARA. BMC Vet. Res. 2016, 12, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Eckel, E.F.; Ametaj, B.N. Invited review: Role of bacterial endotoxins in the etiopathogenesis of periparturient diseases of transition dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2016, 99, 5967–5990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, X.; Mu, R.; Xu, M.; Yuan, X.; Jiang, P.; Guo, J.; Cao, Y.; Zhang, N.; Fu, Y. Gut microbiota mediate the protective effects on endometritis induced by Staphylococcus aureus in mice. Food Funct. 2020, 11, 3695–3705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeon, S.J.; Cunha, F.; Vieira-Neto, A.; Bicalho, R.C.; Lima, S.; Bicalho, M.L.; Galvao, K.N. Blood as a route of transmission of uterine pathogens from the gut to the uterus in cows. Microbiome 2017, 5, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nordlund, K.V.; Garrett, E.F.; Oetzel, G.R. Herd-based rumenocentesis-a clinical approach to the diagnosis of sub acute rumen acidosis. Compend. Contin. Educ. Pract. Vet. 1995, 17, s48–s56. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, R.Y.; Jin, W.; Feng, P.F.; Liu, J.H.; Mao, S.Y. High-grain diet feeding altered the composition and functions of the rumen bacterial community and caused the damage to the laminar tissues of goats. Animal 2018, 12, 2511–2520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delarocque, J.; Reiche, D.B.; Meier, A.D.; Warnken, T.; Feige, K.; Sillence, M.N. Metabolic profile distinguishes laminitis-susceptible and -resistant ponies before and after feeding a high sugar diet. BMC Vet. Res. 2021, 17, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Mu, R.; Li, S.; Zhang, N.; Fu, Y.; Hu, X. Characterization of the Bacterial Community of Rumen in Dairy Cows with Laminitis. Genes 2021, 12, 1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boosman, R.; Koeman, J.; Nap, R. Histopathology of the bovine pododerma in relation to age and chronic laminitis. Zent. Vet. A 1989, 36, 438–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ametaj, B.N.; Zebeli, Q.; Iqbal, S. Nutrition, microbiota, and endotoxin-related diseases in dairy cows. Rev. Bras. De De Zootec. 2010, 39, 433–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nocek, J.E. Bovine acidosis: Implications on laminitis. J. Dairy Dairy Sci. 1997, 80, 1005–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonelli, M.; Kushner, I. It’s time to redefine inflammation. FASEB J. 2017, 31, 1787–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kolb, H.; Mandrup-Poulsen, T. The global diabetes epidemic as a consequence of lifestyle-induced low-grade inflammation. Diabetologia 2010, 53, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Misiak, B.; Leszek, J.; Kiejna, A. Metabolic syndrome, mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease--the emerging role of systemic low-grade inflammation and adiposity. Brain Res. Bull. 2012, 89, 144–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pietrzyk, L.; Torres, A.; Maciejewski, R.; Torres, K. Obesity and Obese-related Chronic Low-grade Inflammation in Promotion of Colorectal Cancer Development. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2015, 16, 4161–4168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chang, G.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Y.; Ma, N.; Chandra, R.A.; Ye, G.; Zhuang, S.; Zhu, W.; Shen, X. Microbial community shifts elicit inflammation in the caecal mucosa via the GPR41/43 signalling pathway during subacute ruminal acidosis. BMC Vet. Res. 2019, 15, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kent-Dennis, C.; Pasternak, A.; Plaizier, J.C.; Penner, G.B. Potential for a localized immune response by the ruminal epithelium in nonpregnant heifers following a short-term subacute ruminal acidosis challenge. J. Dairy Sci. 2019, 102, 7556–7569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khafipour, E.; Krause, D.O.; Plaizier, J.C. A grain-based subacute ruminal acidosis challenge causes translocation of lipopolysaccharide and triggers inflammation. J. Dairy Sci. 2009, 92, 1060–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, K.; Meng, M.; Gao, L.; Tu, Y.; Bai, Y. Rumen-derived lipopolysaccharide induced ruminal epithelium barrier damage in goats fed a high-concentrate diet. Microb. Pathog. 2019, 131, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memon, M.A.; Wang, Y.; Xu, T.; Ma, N.; Zhang, H.; Roy, A.C.; Aabdin, Z.U.; Shen, X. Lipopolysaccharide induces oxidative stress by triggering MAPK and Nrf2 signalling pathways in mammary glands of dairy cows fed a high-concentrate diet. Microb. Pathog. 2019, 128, 268–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahrens, F.A. Histamine, lactic acid, and hypertonicity as factors in the development of rumenitis in cattle. Am. J. Vet. Res. 1967, 28, 1335–1342. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.; Zhang, R.; Zhu, W.; Mao, S. Effects of subacute ruminal acidosis challenges on fermentation and biogenic amines in the rumen of dairy cows. Livest. Sci. 2013, 155, 262–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gozho, G.N.; Krause, D.O.; Plaizier, J.C. Ruminal lipopolysaccharide concentration and inflammatory response during grain-induced subacute ruminal acidosis in dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2007, 90, 856–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Warnberg, J.; Marcos, A. Low-grade inflammation and the metabolic syndrome in children and adolescents. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 2008, 19, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhang, S.; Gan, S.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, L.; Meng, G.; Yao, Z.; Wu, H.; Gu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, T.; et al. Ultra-processed food consumption and the risk of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in the Tianjin Chronic Low-grade Systemic Inflammation and Health Cohort Study. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2022, 51, 237–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joung, H.; Chu, J.; Kim, B.K.; Choi, I.S.; Kim, W.; Park, T.S. Probiotics ameliorate chronic low-grade inflammation and fat accumulation with gut microbiota composition change in diet-induced obese mice models. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2021, 105, 1203–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Won, Y.; Yang, J.I.; Park, S.; Chun, J.S. Lipopolysaccharide Binding Protein and CD14, Cofactors of Toll-like Receptors, Are Essential for Low-Grade Inflammation-Induced Exacerbation of Cartilage Damage in Mouse Models of Posttraumatic Osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2021, 73, 1451–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croci, S.; D’Apolito, L.I.; Gasperi, V.; Catani, M.V.; Savini, I. Dietary Strategies for Management of Metabolic Syndrome: Role of Gut Microbiota Metabolites. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennison, E.; Byrne, C.D. The role of the gut microbiome and.d diet in the pathogenesis of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin. Mol. Hepatol 2021, 27, 22–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, A.L.; Stephens, J.W.; Harris, D.A. Gut microbiota influence in type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). Gut. Pathog. 2021, 13, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, X.; Shang, X.; Liu, J.; Chi, R.; Zhang, J.; Xu, T. The gut microbiota in osteoarthritis: Where do we stand and what can we do? Arthritis Res. Ther. 2021, 23, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bickhart, D.M.; Weimer, P.J. Symposium review: Host-rumen microbe interactions may be leveraged to improve the productivity of dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2018, 101, 7680–7689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeineldin, M.; Barakat, R.; Elolimy, A.; Salem, A.Z.M.; Elghandour, M.M.Y.; Monroy, J.C. Synergetic action between the rumen microbiota and bovine health. Microb. Pathog. 2018, 124, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mu, Y.Y.; Qi, W.P.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, J.Y.; Mei, S.J.; Mao, S.Y. Changes in rumen fermentation and bacterial community in lactating dairy cows with subacute rumen acidosis following rumen content transplantation. J. Dairy Sci. 2021, 104, 10780–10795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Wang, C.; Zhang, H.; Yu, L.; Dong, L.; Gong, D.; Yao, J.; Wang, H. Illumina Sequencing and Metabolomics Analysis Reveal Thiamine Modulation of Ruminal Microbiota and Metabolome Characteristics in Goats Fed a High-Concentrate Diet. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 653283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danscher, A.M.; Li, S.; Andersen, P.H.; Khafipour, E.; Kristensen, N.B.; Plaizier, J.C. Indicators of induced subacute ruminal acidosis (SARA) in Danish Holstein cows. Acta. Vet. Scand. 2015, 57, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Plaizier, J.C.; Li, S.; Danscher, A.M.; Derakshani, H.; Andersen, P.H.; Khafipour, E. Changes in Microbiota in Rumen Digesta and Feces Due to a Grain-Based Subacute Ruminal Acidosis (SARA) Challenge. Microb. Ecol. 2017, 74, 485–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, S.; Zhang, R.; Wang, D.; Zhu, W. Impact of subacute ruminal acidosis (SARA) adaptation on rumen microbiota in dairy cattle using pyrosequencing. Anaerobe 2013, 24, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.Y.; Liu, Y.J.; Yin, Y.Y.; Jin, W.; Mao, S.Y.; Liu, J.H. Response of rumen microbiota, and metabolic profiles of rumen fluid, liver and serum of goats to high-grain diets. Animal 2019, 13, 1855–1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Dong, G.; Wang, Z.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, J.R. Rumen and plasma metabolomics profiling by UHPLC-QTOF/MS revealed metabolic alterations associated with a high-corn diet in beef steers. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0208031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Badoud, F.; Lam, K.P.; Perreault, M.; Zulyniak, M.A.; Britz-McKibbin, P.; Mutch, D.M. Metabolomics Reveals Metabolically Healthy and Unhealthy Obese Individuals Differ in their Response to a Caloric Challenge. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0134613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Anders, H.J.; Andersen, K.; Stecher, B. The intestinal microbiota, a leaky gut, and abnormal immunity in kidney disease. Kidney. Int. 2013, 83, 1010–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hartmann, P.; Chen, W.C.; Schnabl, B. The intestinal microbiome and the leaky gut as therapeutic targets in alcoholic liver disease. Front. Physiol. 2012, 3, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Arya, A.K.; Hu, B. Brain-gut axis after stroke. Brain Circ. 2018, 4, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aschenbach, J.R.; Zebeli, Q.; Patra, A.K.; Greco, G.; Amasheh, S.; Penner, G.B. Symposium review: The importance of the ruminal epithelial barrier for a healthy and productive cow. J. Dairy Sci. 2019, 102, 1866–1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, R.; Zhu, W.; Mao, S. High-concentrate feeding upregulates the expression of inflammation-related genes in the ruminal epithelium of dairy cattle. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2016, 7, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gao, S.; Zhula, A.; Liu, W.; Lu, Z.; Shen, Z.; Penner, G.B.; Ma, L.; Bu, D. Direct effect of lipopolysaccharide and histamine on permeability of the rumen epithelium of steers ex vivo. J. Anim. Sci. 2022, 100, skac005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Yuan, X.; Chen, L.; Wang, T.; Wang, Z.; Sun, G.; Li, X.; Li, X.; Liu, G. Histamine Induces Bovine Rumen Epithelial Cell Inflammatory Response via NF-kappaB Pathway. Cell Physiol. Biochem. 2017, 42, 1109–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilzer, M.; Roggel, F.; Gerbes, A.L. Role of Kupffer cells in host defense and liver disease. Liver. Int. 2006, 26, 1175–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukui, H. Gut-liver axis in liver cirrhosis: How to manage leaky gut and endotoxemia. World J. Hepatol. 2015, 7, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, G.; Liu, X.; Ma, N.; Yan, J.; Dai, H.; Roy, A.C.; Shen, X. Dietary Addition of Sodium Butyrate Contributes to Attenuated Feeding-Induced Hepatocyte Apoptosis in Dairy Goats. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018, 66, 9995–10002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, H.; Wang, S.; Jia, Y.; Ni, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhuang, S.; Shen, X.; Zhao, R. Long-term effects of subacute ruminal acidosis (SARA) on milk quality and hepatic gene expression in lactating goats fed a high-concentrate diet. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e82850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chandra Roy, A.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Roy, S.; Dai, H.; Chang, G.; Shen, X. Sodium Butyrate Mitigates iE-DAP Induced Inflammation Caused by High-Concentrate Feeding in Liver of Dairy Goats. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018, 66, 8999–9009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plaizier, J.; Khafipour, E.; Li, S.; Gozho, G.; Krause, D. Subacute ruminal acidosis (SARA), endotoxins and health consequences. Anim. Feed. Sci. Technol. 2012, 172, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, D.; Chang, G.; Zhang, K.; Guo, J.; Xu, T.; Shen, X. Rumen-derived lipopolysaccharide enhances the expression of lingual antimicrobial peptide in mammary glands of dairy cows fed a high-concentrate diet. BMC Vet. Res. 2016, 12, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhao, C.; Liu, G.; Li, X.; Guan, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yuan, X.; Sun, G.; Wang, Z.; Li, X. Inflammatory mechanism of Rumenitis in dairy cows with subacute ruminal acidosis. BMC Vet. Res. 2018, 14, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohtsu, H. Histamine synthesis and lessons learned from histidine decarboxylase deficient mice. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2010, 709, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garner, M.R.; Gronquist, M.R.; Russell, J.B. Nutritional requirements of Allisonella histaminiformans, a ruminal bacterium that decarboxylates histidine and produces histamine. Curr. Microbiol. 2004, 49, 295–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, G.; Wang, L.; Ma, N.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, H.; Dai, H.; Shen, X. Histamine activates inflammatory response and depresses casein synthesis in mammary gland of dairy cows during SARA. BMC Vet. Res. 2018, 14, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hua, C.; Tian, J.; Tian, P.; Cong, R.; Luo, Y.; Geng, Y.; Tao, S.; Ni, Y.; Zhao, R. Feeding a High Concentration Diet Induces Unhealthy Alterations in the Composition and Metabolism of Ruminal Microbiota and Host Response in a Goat Model. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vermunt, J.; Greenough, P. Predisposing factors of laminitis in cattle. Br. Vet. J. 1994, 150, 151–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garner, M.R.; Flint, J.F.; Russell, J.B. Allisonella histaminiformans gen. nov., sp. nov.: A novel bacterium that produces histamine, utilizes histidine as its sole energy source, and could play a role in bovine and equine laminitis. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 2002, 25, 498–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, J.; Huang, J.; Chang, G.; Roy, A.C.; Gao, Q.; Cheng, X.; Shen, X. Sodium butyrate attenuated iE-DAP induced inflammatory response in the mammary glands of dairy goats fed high-concentrate diet. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2021, 101, 1218–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Q.; Wang, Y.; Ma, N.; Dai, H.; Roy, A.C.; Chang, G.; Shi, X.; Shen, X. Sodium valproate attenuates the iE-DAP induced inflammatory response by inhibiting the NOD1-NF-κB pathway and histone modifications in bovine mammary epithelial cells. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2020, 83, 106392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garner, H.E.; Hutcheson, D.P.; Coffman, J.R.; Hahn, A.W.; Salem, C. Lactic acidosis: A factor associated with equine laminitis. J. Anim. Sci. 1977, 45, 1037–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manosalva, C.; Quiroga, J.; Teuber, S.; Cárdenas, S.; Carretta, M.D.; Morán, G.G.; Alarcón, P.; Hidalgo, M.A.; Burgos, R.A. D-Lactate Increases Cytokine Production in Bovine Fibroblast-Like Synoviocytes via MCT1 Uptake and the MAPK, PI3K/Akt, and NFκB Pathways. Animals 2020, 10, 2105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrow, L.L.; Tumbleson, M.E.; Kintner, L.D.; Pfander, W.H.; Preston, R.L. Laminitis in lambs injected with lactic acid. Am. J. Vet. Res. 1973, 34, 1305–1307. [Google Scholar]

- Mu, Y.; Qi, W.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, J.; Mao, S. Multi-omics Analysis Revealed Coordinated Responses of Rumen Microbiome and Epithelium to High-Grain-Induced Subacute Rumen Acidosis in Lactating Dairy Cows. mSystems 2022, 7, e0149021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolochow, H.; Hildebrand, G.J.; Lamanna, C. Translocation of microorganisms across the intestinal wall of the rat: Effect of microbial size and concentration. J. Infect. Dis. 1966, 116, 523–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekirov, I.; Russell, S.L.; Antunes, L.C.; Finlay, B.B. Gut microbiota in health and disease. Physiol. Rev. 2010, 90, 859–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yang, X.; Lu, D.; Zhuo, J.; Lin, Z.; Yang, M.; Xu, X. The Gut-liver Axis in Immune Remodeling: New insight into Liver Diseases. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2020, 16, 2357–2366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Huang, L.; Luo, M.; Xia, X. Bacterial translocation in acute pancreatitis. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2019, 45, 539–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selma-Royo, M.; Calvo Lerma, J.; Cortes-Macias, E.; Collado, M.C. Human milk microbiome: From actual knowledge to future perspective. Semin. Perinatol. 2021, 45, 151450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carron, C.; Pais de Barros, J.P.; Gaiffe, E.; Deckert, V.; Adda-Rezig, H.; Roubiou, C.; Laheurte, C.; Masson, D.; Simula-Faivre, D.; Louvat, P.; et al. End-Stage Renal Disease-Associated Gut Bacterial Translocation: Evolution and Impact on Chronic Inflammation and Acute Rejection After Renal Transplantation. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jeon, S.J.; Lima, F.S.; Vieira-Neto, A.; Machado, V.S.; Lima, S.F.; Bicalho, R.C.; Santos, J.E.P.; Galvao, K.N. Shift of uterine microbiota associated with antibiotic treatment and cure of metritis in dairy cows. Vet. Microbiol. 2018, 214, 132–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Morrison, M.; Yu, Z. Status of the phylogenetic diversity census of ruminal microbiomes. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2011, 76, 49–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wirusanti, N.I.; Baldridge, M.T.; Harris, V.C. Microbiota regulation of viral infections through interferon signaling. Trends Microbiol. 2022, 1, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isles, N.S.; Mu, A.; Kwong, J.C.; Howden, B.P.; Stinear, T.P. Gut microbiome signatures and host colonization with multidrug-resistant bacteria. Trends Microbiol. 2022, 01, 013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clavel, T.; Gomes-Neto, J.C.; Lagkouvardos, I.; Ramer-Tait, A.E. Deciphering interactions between the gut microbiota and the immune system via microbial cultivation and minimal microbiomes. Immunol. Rev. 2017, 279, 8–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tranah, T.H.; Edwards, L.A.; Schnabl, B.; Shawcross, D.L. Targeting the gut-liver-immune axis to treat cirrhosis. Gut 2021, 70, 982–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Huang, S.; Wang, Y.; Cai, S.; Yu, H.; Liu, H.; Zeng, X.; Zhang, G.; Qiao, S. Bridging intestinal immunity and gut microbiota by metabolites. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2019, 76, 3917–3937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, X. Probiotics Regulate Gut Microbiota: An Effective Method to Improve Immunity. Molecules 2021, 26, 6076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plaizier, J.C.; Danesh Mesgaran, M.; Derakhshani, H.; Golder, H.; Khafipour, E.; Kleen, J.L.; Lean, I.; Loor, J.; Penner, G.; Zebeli, Q. Review: Enhancing gastrointestinal health in dairy cows. Animal 2018, 12, s399–s418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Humer, E.; Aditya, S.; Zebeli, Q. Innate immunity and metabolomic responses in dairy cows challenged intramammarily with lipopolysaccharide after subacute ruminal acidosis. Animal 2018, 12, 2551–2560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, K.; Zhao, M.M.; Liu, L.; Khogali, M.K.; Geng, T.Y.; Wang, H.R.; Gong, D.Q. Thiamine modulates intestinal morphological structure and microbiota under subacute ruminal acidosis induced by a high-concentrate diet in Saanen goats. Animal 2021, 15, 100370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmhadi, M.E.; Ali, D.K.; Khogali, M.K.; Wang, H. Subacute ruminal acidosis in dairy herds: Microbiological and nutritional causes, consequences, and prevention strategies. Anim. Nutr. 2022, 10, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mizuguchi, H.; Ikeda, T.; Watanabe, Y.; Kushibiki, S.; Ikuta, K.; Kim, Y.-H.; Sato, S. Anti-lipopolysaccharide antibody administration mitigates ruminal lipopolysaccharide release and depression of ruminal pH during subacute ruminal acidosis challenge in Holstein bull cattle. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2021, 83, 905–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizuguchi, H.; Kizaki, K.; Kimura, A.; Kushibiki, S.; Ikuta, K.; Kim, Y.-H.; Sato, S. Anti-lipopolysaccharide antibody mitigates ruminal lipopolysaccharide release without acute-phase inflammation or liver transcriptomic responses in Holstein bulls. J. Vet. Sci. 2021, 22, e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DePeters, E.; George, L. Rumen transfaunation. Immunol. Lett. 2014, 162, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Ji, S.; Duan, C.; Ju, S.; Zhang, Y.; Yan, H.; Liu, Y. Rumen fluid transplantation affects growth performance of weaned lambs by altering gastrointestinal microbiota, immune function and feed digestibility. Animal 2021, 15, 100076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Li, H.; Zhu, W.; Mao, S. Dynamic changes in rumen fermentation and bacterial community following rumen fluid transplantation in a sheep model of rumen acidosis: Implications for rumen health in ruminants. FASEB J. 2019, 33, 8453–8467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Inflammatory Biomarkers | Animal Species/Test Samples | Disease Group Animals | Control Group Animals |

|---|---|---|---|

| LPS | Goat/Cecal contents | 19,889.47 a ± 2917.37 EU/mL | 7257.01 ± 1020.43 EU/mL [47] |

| Cattle/Rumen fluid | 51,481 a EU/mL | 13,331 EU/mL [48] | |

| Dairy cows/Rumen fluid | 151,985 a EU mL | 29,492 EU/mL [49] | |

| Dairy cows/Peripheral blood | 0.81 a EU/mL | <0.05 EU/mL [49] | |

| Dairy cows/Rumen fluid | 89.3 a kEU/mL | 34.2 kEU/mL [50] | |

| Dairy cows/Peripheral blood | 0.37 a EU/mL | 0.16 EU/mL [50] | |

| Dairy cows/Rumen fluid | 78.43 a kEU/mL | 47.47 kEU/mL [51] | |

| Dairy cows/lacteal artery plasma | 0.85 a EU/mL | 0.45 EU/mL [51] | |

| Dairy cows/lacteal vein plasma | 0.25 a EU/mL | 0.15 EU/mL [51] | |

| Dairy cows/Feces | 252,345 a EU/g | 3514 EU/g [51] | |

| Histamine | Dairy cows/Rumen fluid | 64 a μmol/L | 0.5 μmol/L [52] |

| Dairy cows/Peripheral blood | 0.2 a μmol/L | <0.009 μmol/L [52] | |

| Dairy cows/Rumen fluid | 161.2 ** μmol/L | 46.4 μmol/L [53] | |

| Dairy cows/Peripheral blood | 7.92 ** μmol/L | 2.03 μmol/L [53] | |

| TNF-α | Dairy cows/Peripheral blood | 18.56 a fmol/mL | 9.83 fmol/mL [50] |

| IL-1β | Dairy cows/Peripheral blood | 1.07 a ng/mL | 0.32 ng/mL [50] |

| IL-6 | Dairy cows/Peripheral blood | 532.18 a pg/mL | 98.36 pg/mL [50] |

| SAA | Dairy cows/Peripheral blood | 446.7 a μg/mL | 164.4 μg/mL [49] |

| Dairy cows/Peripheral blood | 498.8 a μg/mL | 286.8 μg/mL [54] | |

| Dairy cows/Peripheral blood | 170.7 a ± 36.53μg/mL | 33.6 ± 36.53 μg/mL [5] | |

| Hp | Dairy cows/Peripheral blood | 484 a μg/mL | <50 μg/mL [49] |

| Dairy cows/Peripheral blood | 265 a μg/mL | 244 μg/mL [54] | |

| Beef cattle/Peripheral blood | 0.79 a ± 0.14 mg/mL | 0.43 ± 0.14 mg/mL [5] | |

| LBP | Dairy cows/Peripheral blood | 53.1 a μg/mL | 18.2 μg/mL [49] |

| Dairy cows/Milk | 6.94 a μg/mL | 3.02 μg/mL [49] | |

| WBC | Dairy cows/Peripheral blood | 5.69 × 109/L | 5.23 × 109/L [54] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fu, Y.; He, Y.; Xiang, K.; Zhao, C.; He, Z.; Qiu, M.; Hu, X.; Zhang, N. The Role of Rumen Microbiota and Its Metabolites in Subacute Ruminal Acidosis (SARA)-Induced Inflammatory Diseases of Ruminants. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1495. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms10081495

Fu Y, He Y, Xiang K, Zhao C, He Z, Qiu M, Hu X, Zhang N. The Role of Rumen Microbiota and Its Metabolites in Subacute Ruminal Acidosis (SARA)-Induced Inflammatory Diseases of Ruminants. Microorganisms. 2022; 10(8):1495. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms10081495

Chicago/Turabian StyleFu, Yunhe, Yuhong He, Kaihe Xiang, Caijun Zhao, Zhaoqi He, Min Qiu, Xiaoyu Hu, and Naisheng Zhang. 2022. "The Role of Rumen Microbiota and Its Metabolites in Subacute Ruminal Acidosis (SARA)-Induced Inflammatory Diseases of Ruminants" Microorganisms 10, no. 8: 1495. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms10081495

APA StyleFu, Y., He, Y., Xiang, K., Zhao, C., He, Z., Qiu, M., Hu, X., & Zhang, N. (2022). The Role of Rumen Microbiota and Its Metabolites in Subacute Ruminal Acidosis (SARA)-Induced Inflammatory Diseases of Ruminants. Microorganisms, 10(8), 1495. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms10081495