An Adaptive Harmonics Suppression Strategy Using a Proportional Multi-Resonant Controller Based on Generalized Frequency Selector for PMSM

Abstract

1. Introduction

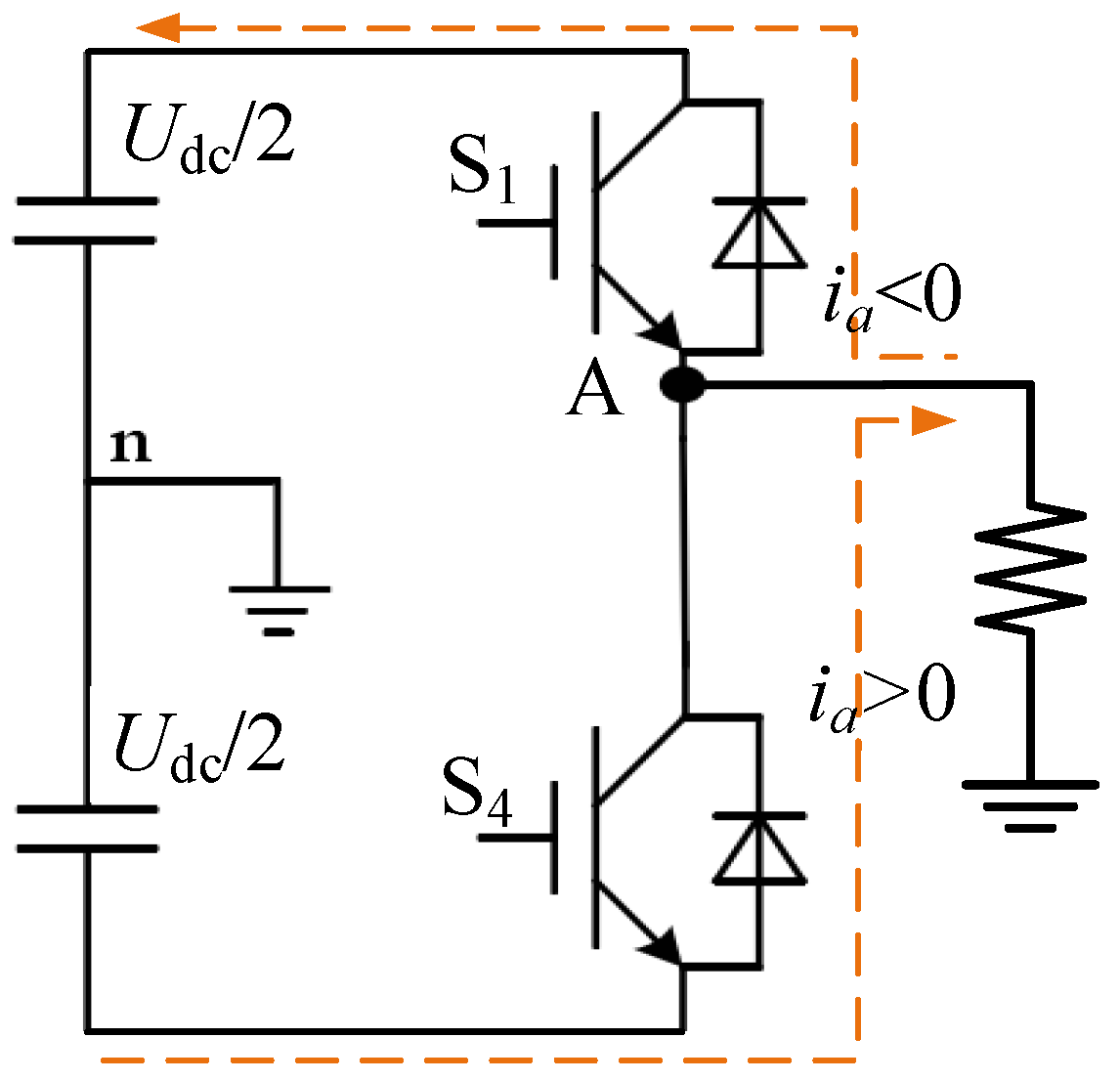

2. Current Harmonics in PMSM

2.1. Sources of Low-Order Harmonics

2.2. Harmonics Modeling in the d-q Coordinate System

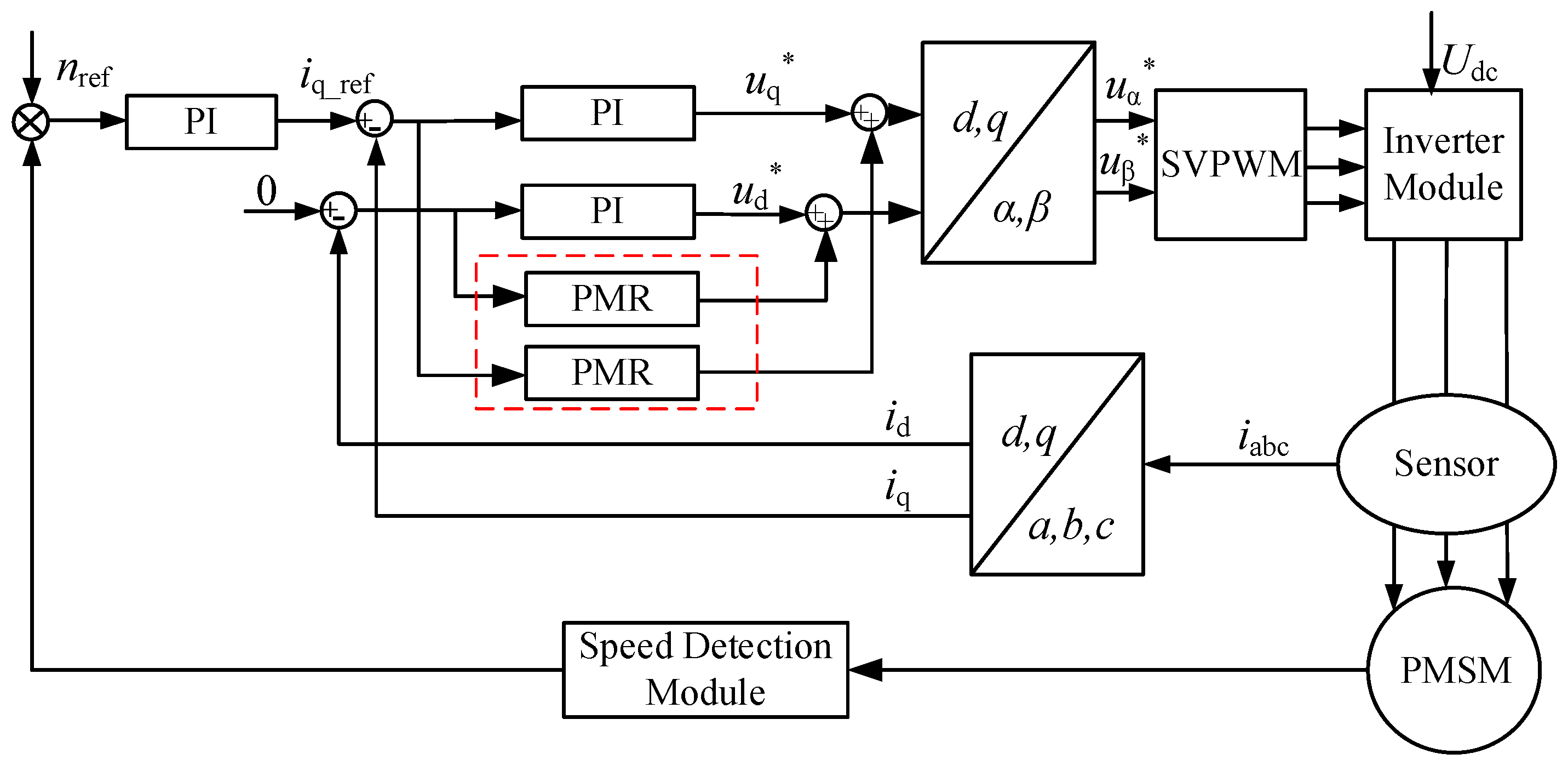

3. PMSM Current Harmonic Suppression

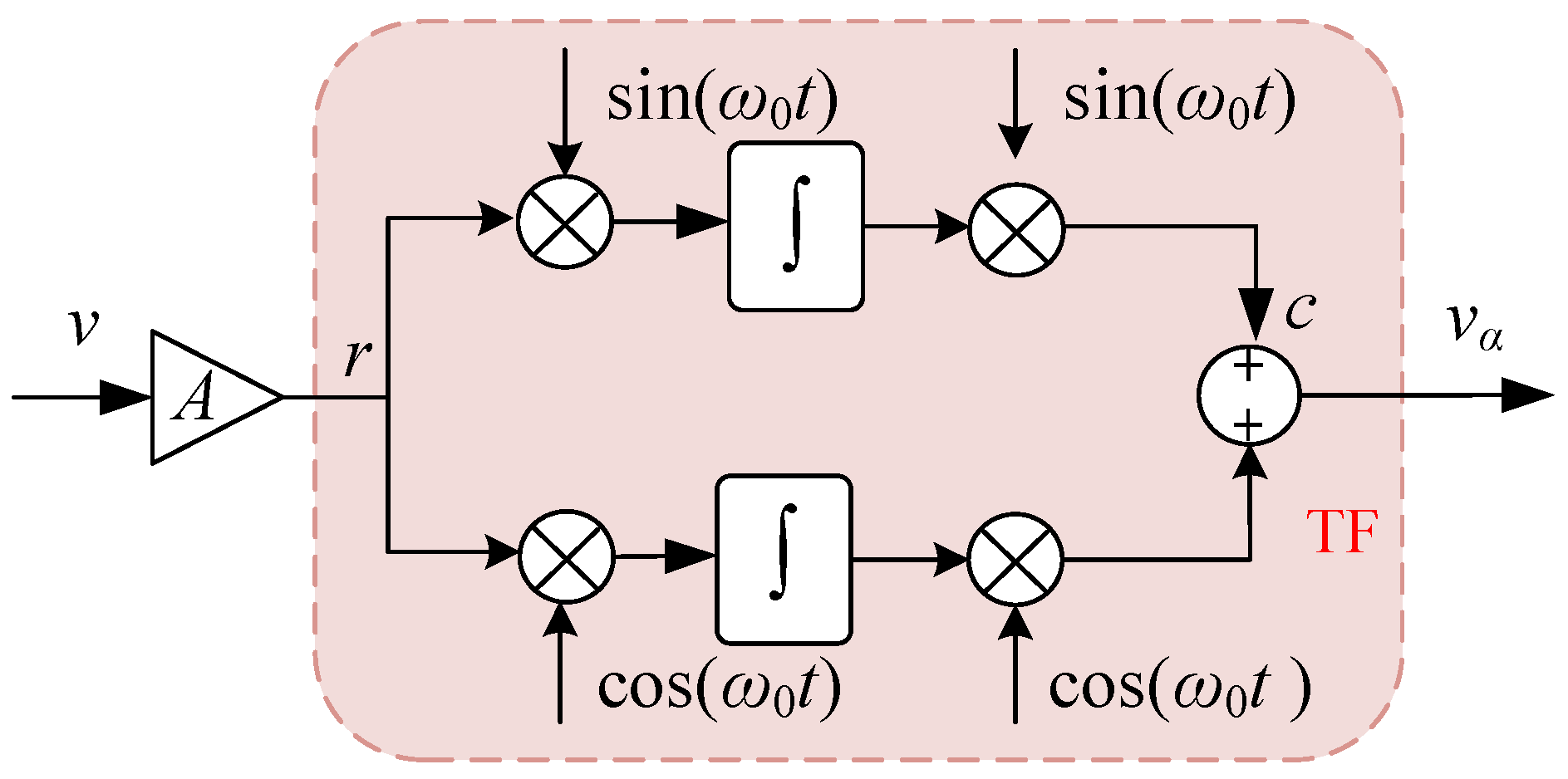

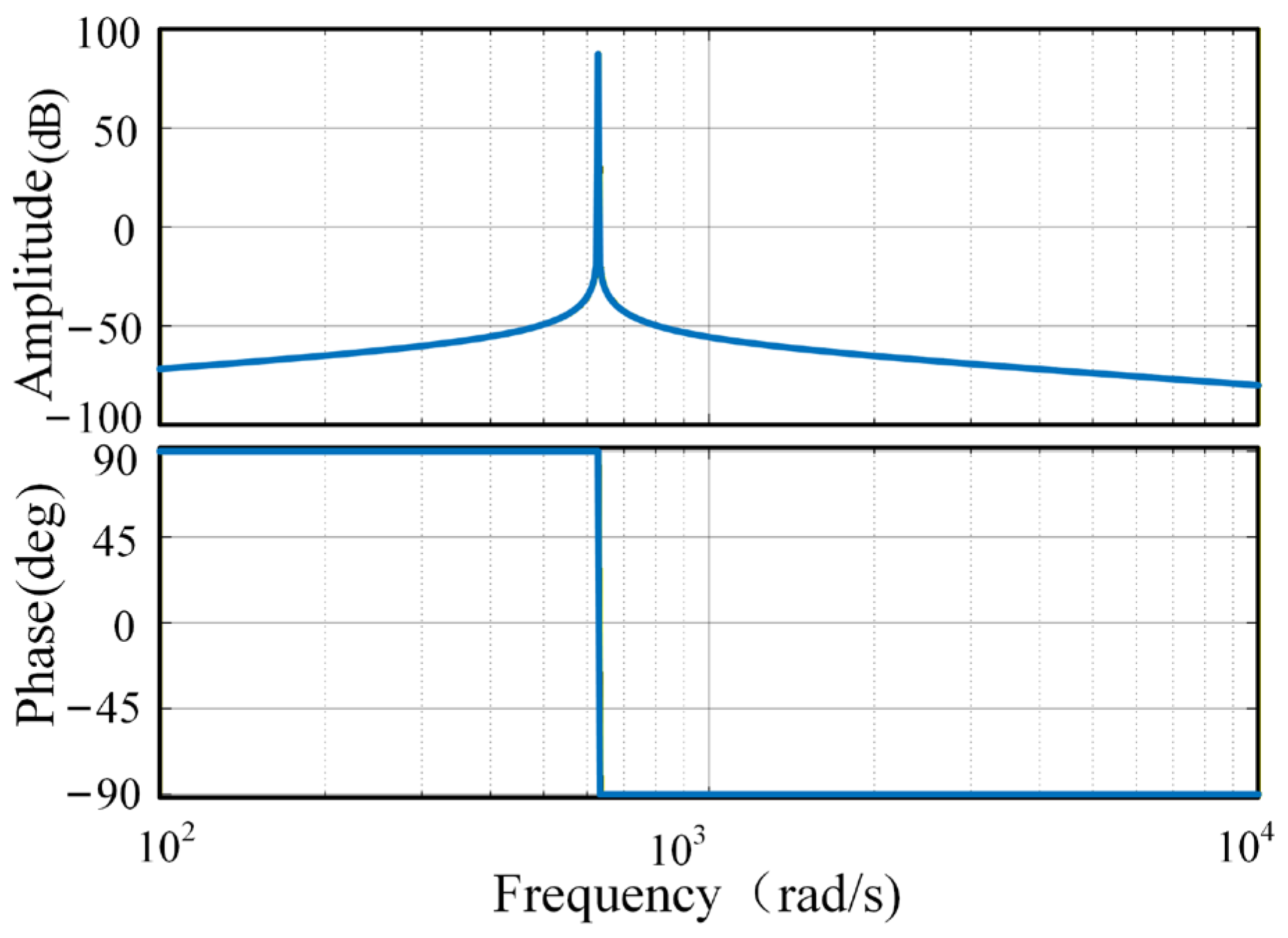

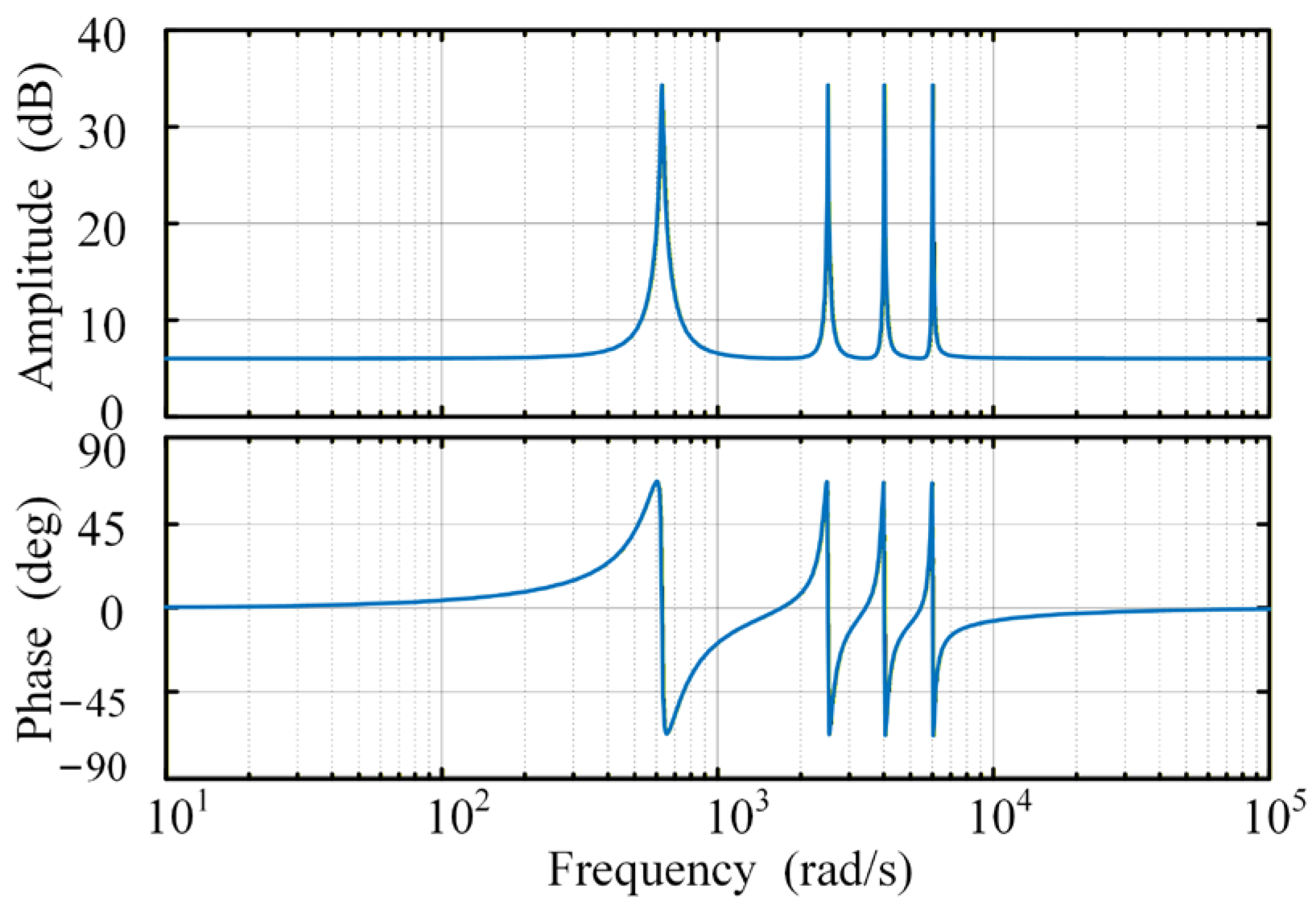

3.1. PMR Controller Design

3.2. Stability Analysis

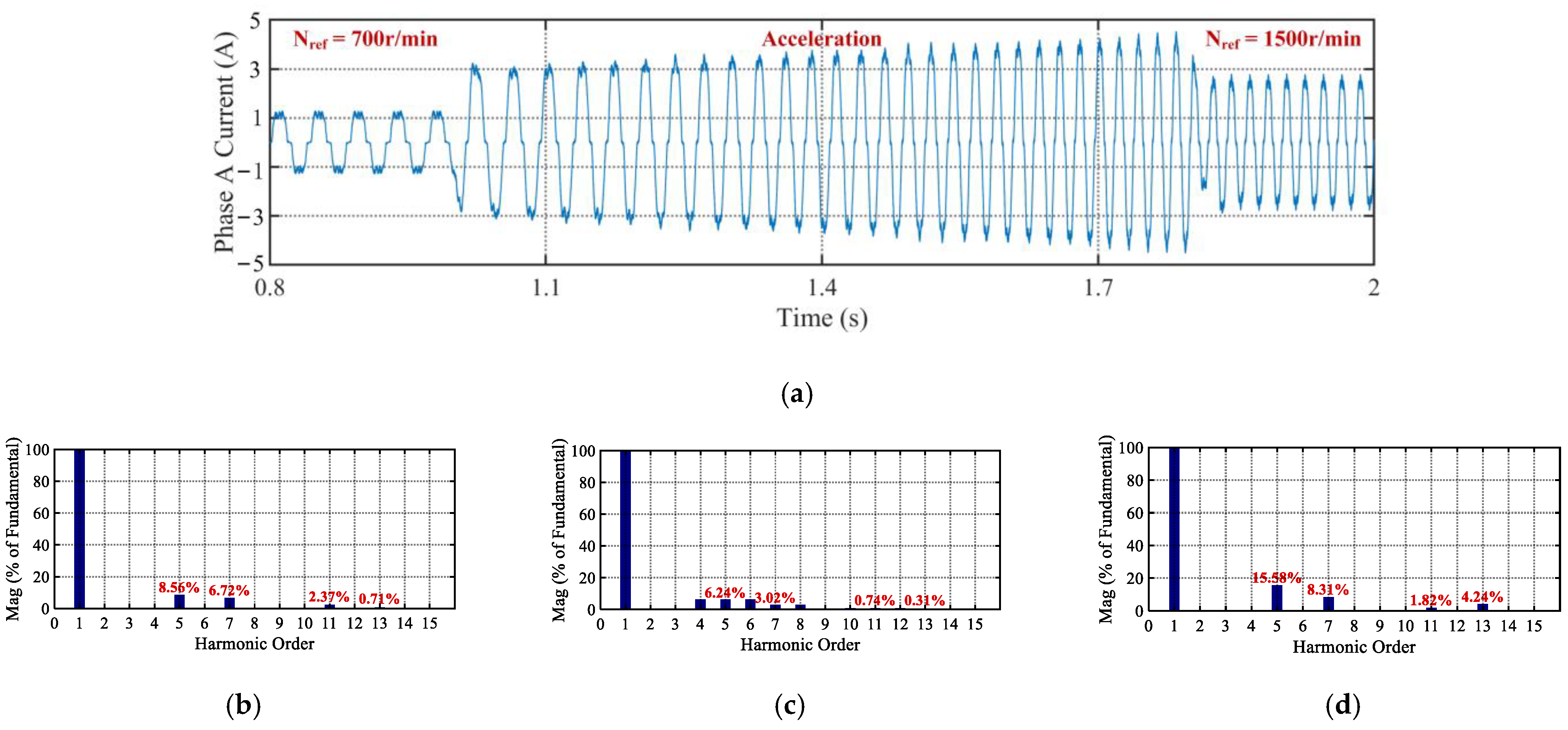

4. Simulation Analysis of PMR Controller

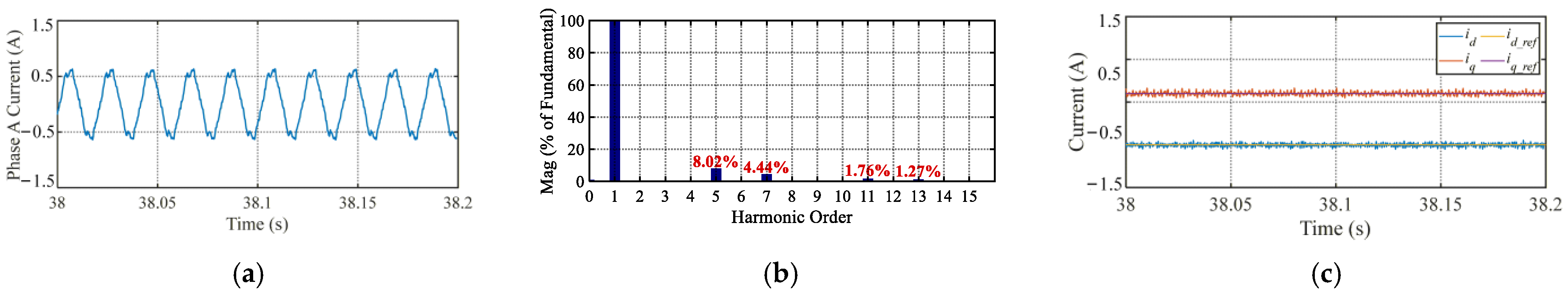

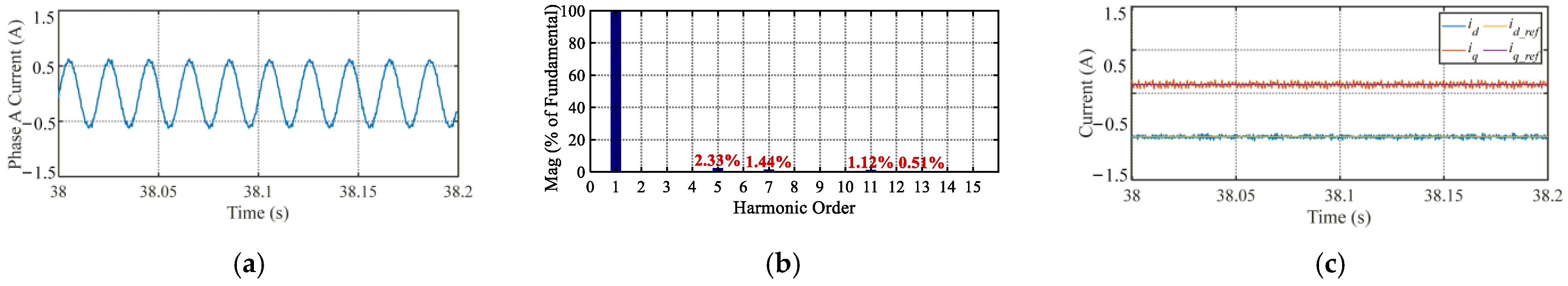

5. Experimental Study

5.1. Experimental Setup

5.2. Experimental Design

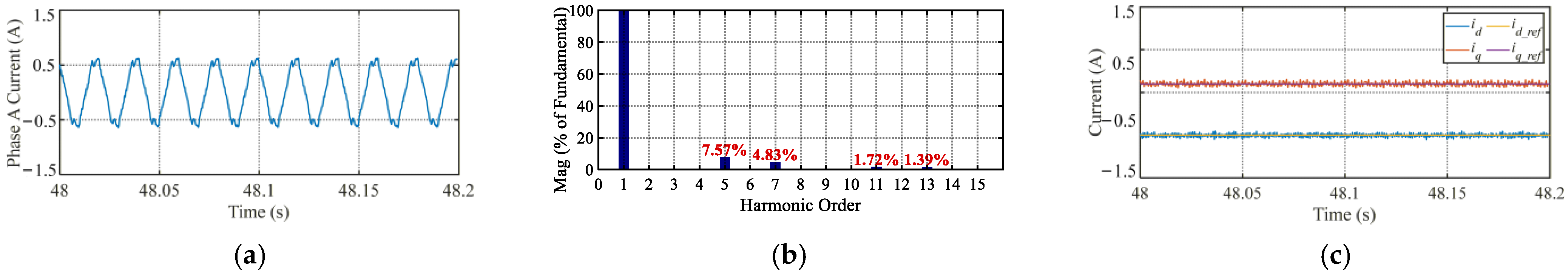

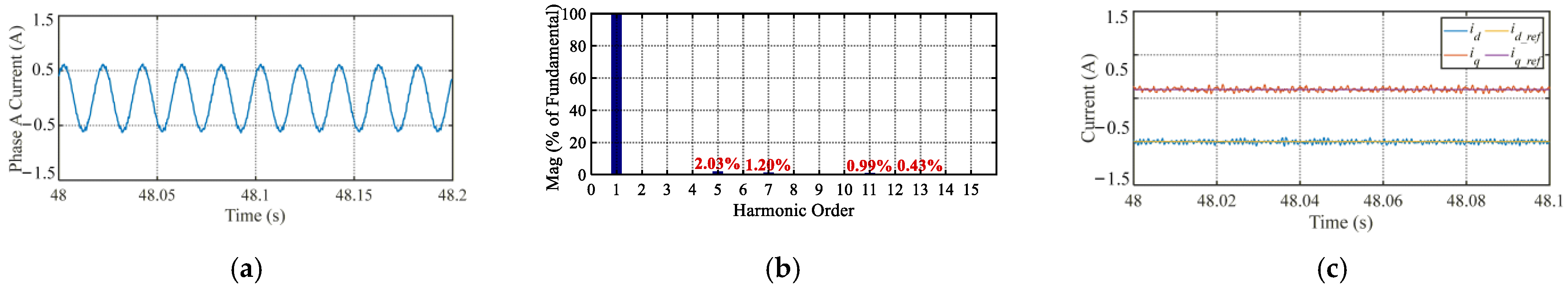

5.3. Experimental Results

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yan, L.; Zhu, Z.; Shao, B.; Qi, J.; Ren, Y.; Gan, C.; Brockway, S.; Hilton, C. Arbitrary current harmonic decomposition and regulation for permanent magnet synchronous machines. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2022, 72, 4392–4404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okamoto, S.; Denis, N.; Kato, Y.; Ieki, M.; Fujisaki, K. Core loss reduction of an interior permanent-magnet synchronous electrical machine using amorphous stator core. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2016, 52, 2261–2268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, Z.; Song, W.; Yan, Y. Current harmonic suppression for dual three-phase permanent magnet synchronous motor drives. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 177764–177773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Xu, J.; Chen, Q.; Chen, Z.; Huang, R. An Improved Trapezoidal Voltage Method for Dead-Time Compensation in Three-Phase Voltage Source Converter. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2022, 37, 8785–8789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, C.; Yu, J.; Du, P.; Li, L. Analytical model of magnetic field of a permanent magnet synchronous motor with a trapezoidal Halbach permanent magnet array. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2019, 55, 8105205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras, M.D.J.; Kazemikia, D.; Khan, S.; Gardner, M. A Parameterized Nonlinear Magnetic Equivalent Circuit Model for Fast Design and Comparison of Surface Permanent Magnet Synchronous Machines. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE International Electric Machines & Drives Conference, Houston, TX, USA, 18–21 May 2025; pp. 1040–1045. [Google Scholar]

- Seadati, S.A.S.; Niasar, A.H. Optimal design and finite element analysis of a high speed, axial-flux permanent magnet synchronous motor. In Proceedings of the Annual Power Electronics, Drives Systems and Technologies Conference, Tehran, Iran, 13–15 February 2018; pp. 462–467. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, C.; Ding, L.; Li, Y. Model predictive control with reduced common-mode current for transformerless current-source PMSM drives. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2021, 36, 8114–8127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkataraman, G. Evaluation of Inverter Topology Options for Low Inductance Motors. In Proceedings of the Conference Record of the 1993 IEEE Industry Applications Conference Twenty-Eighth IAS Annual Meeting, Toronto, ON, Canada, 2–8 October 1993; pp. 1041–1047. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, T.; Zhang, X.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, G.; Yi, H. A LCCR Filter Based Harmonic Suppression Method for Power Quality Improvement. Energy Rep. 2023, 9, 549–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essien, A.U.; Ilo, F.U.; Udebunu, F. Modelling, Design and Performance Analysis of LCL Filter for Grid Connected Three Phase Power Converters. J. Energy Res. Rev. 2022, 12, 36–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Wang, D.; Jin, Y.; Wang, M.; Zhang, P. Current-detection-independent dead-time compensation method based on terminal voltage A/D conversion for PWM VSI. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2017, 64, 7689–7699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Z.; Lin, X.; Liu, Z.; Shen, X.; Gao, Y.; Liu, J. Adaptive Generalized Super-Twisting Sliding Mode Control for PMSM Drives. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Z.; Lin, X.; Shen, X.; Liu, Z.; Gao, Y.; Liu, J. Event-Triggered Generalized Super-Twisting Sliding Mode Control for Position Tracking of PMSMs. IEEE Trans Ind. Informat. 2025, 21, 5701–5711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, D.; Chakraborty, C.; Dalapati, S. Current Sensor-Less Dead Time Distortion Compensation in Single-Phase PWM Inverter. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2025, 72, 4696–4709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhou, J.; Miao, H.; Liang, T.; Ge, Y. Research on Minimizing Speed Harmonics of PMSM by Injecting Voltage Harmonics Based on Second-Order Generalized Integrator. In Proceedings of the 2024 14th International Conference on Power and Energy Systems (ICPES), Chengdu, China, 13–16 December 2024; pp. 47–51. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Miao, Q.; Zeng, P.; Lin, Z.; Li, Y.; Li, X. Multiple Synchronous Rotating Frame Transformation-Based 12th Current Harmonic Suppression Method for an IPMSM. World Electr. Veh. J. 2022, 13, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, G.; Li, Y.; Jin, W.; Bu, L. A nonlinear three-phase phase-locked loop based on linear active disturbance rejection controller. IEEE Access 2017, 5, 21548–21556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benrabah, A.; Xu, D.; Guo, Z. Active disturbance rejection control of LCL filtered grid-connected inverter using Padé approximation. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2018, 54, 6179–6189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Yang, J.; Mei, X.; Tao, T.; Xu, M. Harmonic current suppression method with adaptive filter for permanent magnet synchro-nous motor. Int. J. Electron. 2021, 108, 983–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Song, X.; Li, H.; Chen, B. Suppression of harmonic current in permanent magnet synchro-nous motors using improved repetitive controller. Electron. Lett. 2019, 55, 47–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Liu, C.; Liu, S.; Song, Z.; Zhao, H.; Dai, B. Current harmonic suppression for permanent magnet synchronous motor based on Chebyshev filter and PI controller. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2021, 57, 8201406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, S.; Cho, H.; Choi, S. Design and analysis of a high-speed brushless DC motor for centrifugal compressor. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 2012, 27, 646–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golestan, S.; Guerrero, J.M.; Musavi, F.; Vasquez, J.C. Single-phase frequency-locked loops: A comprehensive review. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2019, 34, 11791–11811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Zheng, B.; Wang, G.; Yan, H.; Zou, J. Current harmonic suppression in dual three-phase permanent magnet synchronous machine with extended state observer. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2020, 35, 12166–12180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golestan, S.; Ebrahimzadeh, E.; Guerrero, J.M.; Vasquez, J.C. An adaptive resonant regulator for single-phase grid-tied VSCs. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2018, 33, 2207–2217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Coordinate System | Voltage Harmonic Order | Current Harmonic Order |

|---|---|---|

| A-B-C | 6k ± 1 | 6k ± 1 |

| α-β | 6k ± 1 | 6k ± 1 |

| d-q | 6k | 6k |

| Parameter | Value | Parameter | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pole pairs | 2 | Phase resistance | 2.4/ohm |

| Flux linkage | 0.06/wb | Switching frequency | 10/kHz |

| d- and q-axis inductance | 4.2/mH | Inverter dead time | 5/μs |

| Rated power | 1.5 KW | Rated torque | 10 N·m |

| Rated speed | 1500 RPM | Rated current | 6 A |

| Description | Role |

|---|---|

| Motor | Actuator |

| Incremental Encoder | Detects rotor position |

| Encoder Signal Conversion Module | Processes position feedback signals |

| Motor Driver | Drives the motor via PWM signals |

| dSPACE1202 | Executes real-time control; Processes feedback |

| Hall Current Sensor | Detects phase currents |

| Host Computer | Compiles code; Monitors data |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zeng, K.; Zheng, Y.; Xu, Y.; Gao, Q.; Zhou, J. An Adaptive Harmonics Suppression Strategy Using a Proportional Multi-Resonant Controller Based on Generalized Frequency Selector for PMSM. Actuators 2026, 15, 76. https://doi.org/10.3390/act15020076

Zeng K, Zheng Y, Xu Y, Gao Q, Zhou J. An Adaptive Harmonics Suppression Strategy Using a Proportional Multi-Resonant Controller Based on Generalized Frequency Selector for PMSM. Actuators. 2026; 15(2):76. https://doi.org/10.3390/act15020076

Chicago/Turabian StyleZeng, Kun, Yawei Zheng, Yuanping Xu, Qingli Gao, and Jin Zhou. 2026. "An Adaptive Harmonics Suppression Strategy Using a Proportional Multi-Resonant Controller Based on Generalized Frequency Selector for PMSM" Actuators 15, no. 2: 76. https://doi.org/10.3390/act15020076

APA StyleZeng, K., Zheng, Y., Xu, Y., Gao, Q., & Zhou, J. (2026). An Adaptive Harmonics Suppression Strategy Using a Proportional Multi-Resonant Controller Based on Generalized Frequency Selector for PMSM. Actuators, 15(2), 76. https://doi.org/10.3390/act15020076