A Wall-Climbing Robot with a Mechanical Arm for Weld Inspection of Large Pressure Vessels

Abstract

1. Introduction

- A hierarchical motion planning–based weld traversal strategy that ensures complete inspection coverage in large, curved, and segmented environments, demonstrating strong adaptability to diverse pressure vessel geometries.

- An advanced weld seam identification framework that integrates DBNet and SVTR network architectures, incorporating improvements in bottom-up path design and spatial–channel feature extraction. This method achieves high detection accuracy while maintaining real-time performance in experimental evaluations.

2. System Scheme

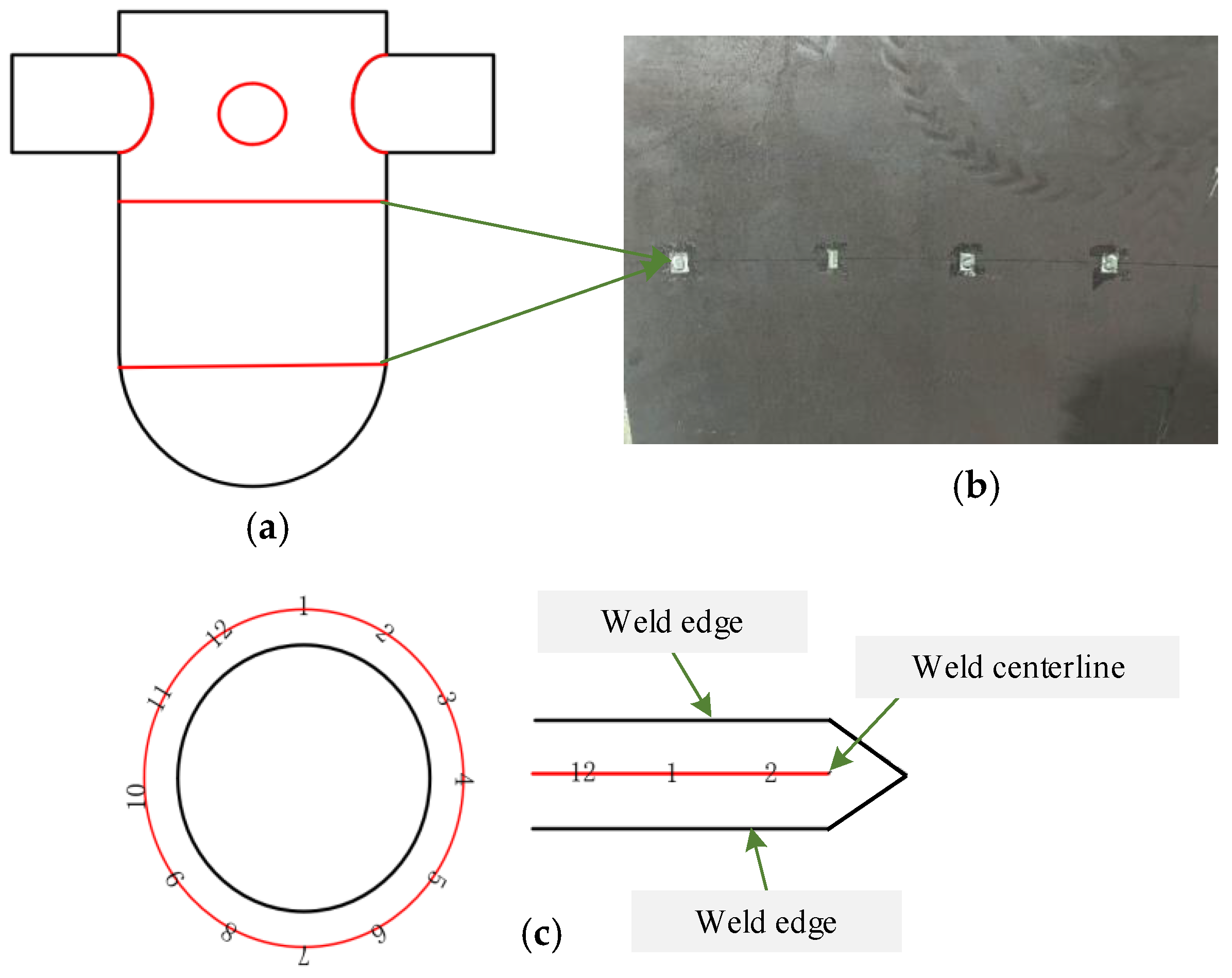

2.1. Working Environment and Requirements

- The system must be capable of planning and executing complete traversal paths for all weld seams distributed along the vessel’s inner wall.

- It should perform weld detection and localization using steel stamp markers in low-feature environments.

- It must ensure high-precision tracking of weld seams across large, curved surfaces.

- The inspection system should achieve a weld coverage rate of at least 97%.

- Weld seam localization accuracy in low-feature regions should exceed 95%, with positional deviations within 2 mm.

- The tracking accuracy for weld seams should be maintained within 3 mm.

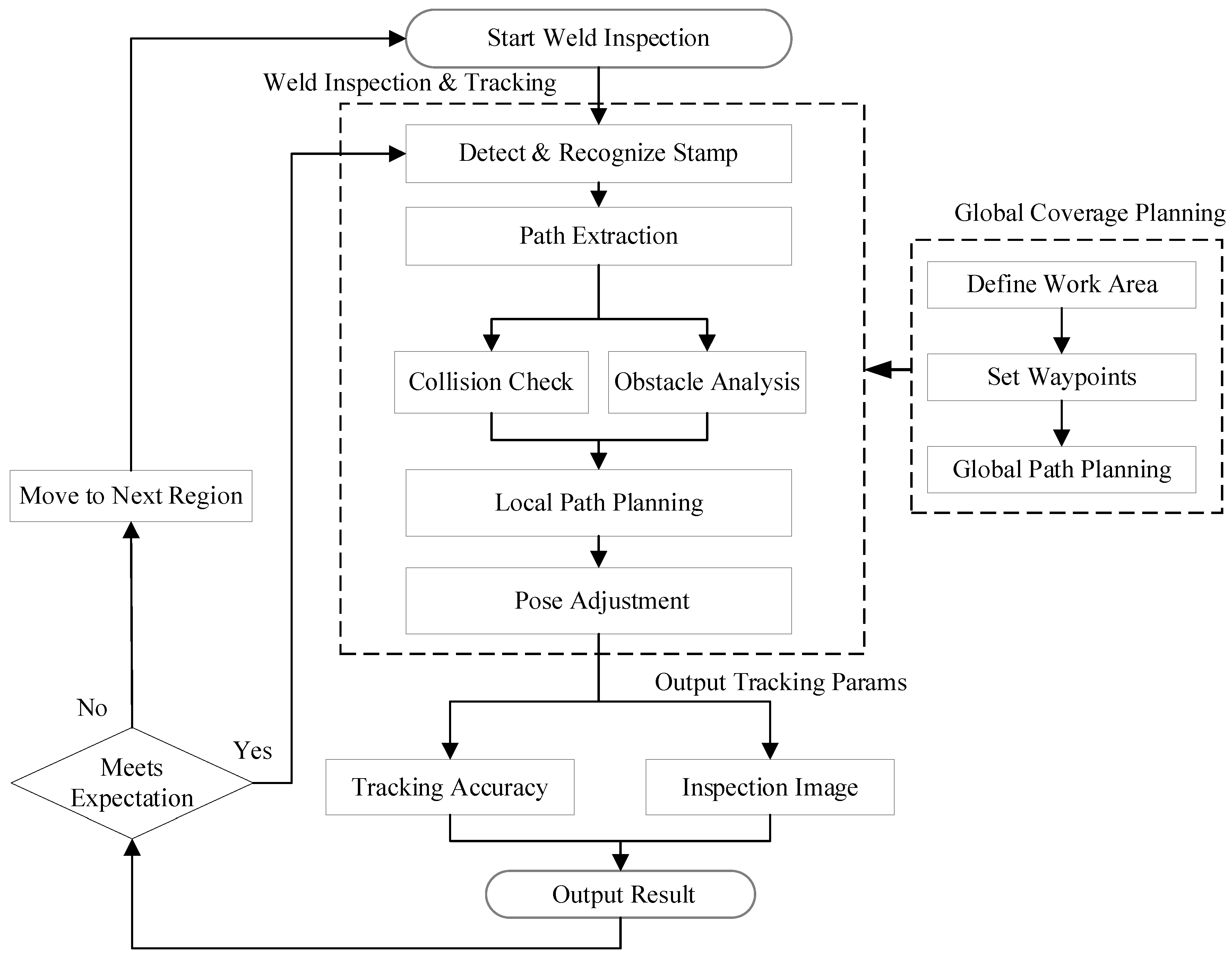

2.2. Overall Program

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Weld Traversal and Inspection Methods for Large Pressure Vessels

3.1.1. Global Path Planning Strategy Based on the A Algorithm*

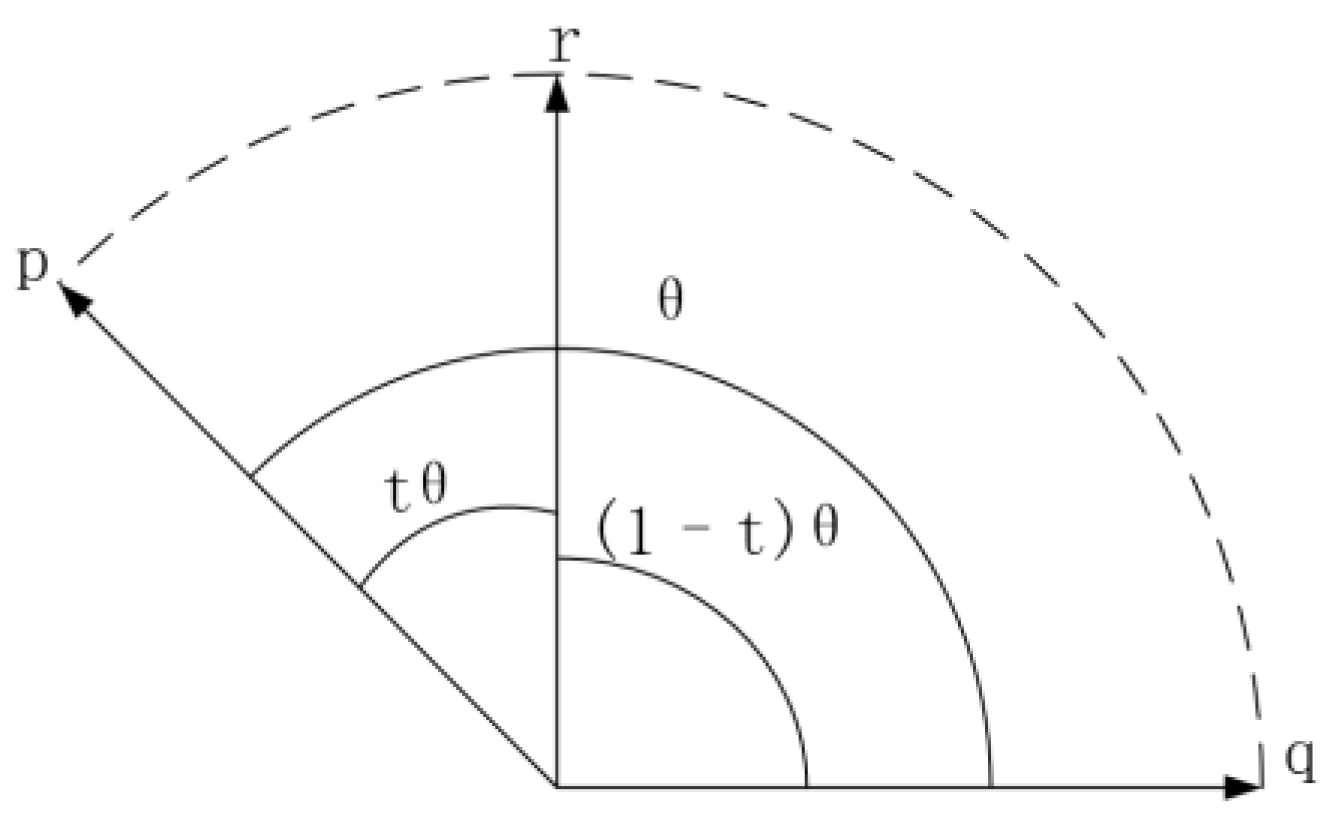

3.1.2. Local Motion Planning for Precise Weld Tracking

- denote the angle between and ;

- denotes the time at which the interpolated orientation is .

3.2. Weld Seam Path Detection and Extraction Using Digital Nameplate Information

3.2.1. OCR-Based Nameplate Detection and Recognition Using an Improved Algorithm

3.2.2. Improved Digital Stamp Detection Algorithm

- Integration of a Convolutional Attention Module

- 2.

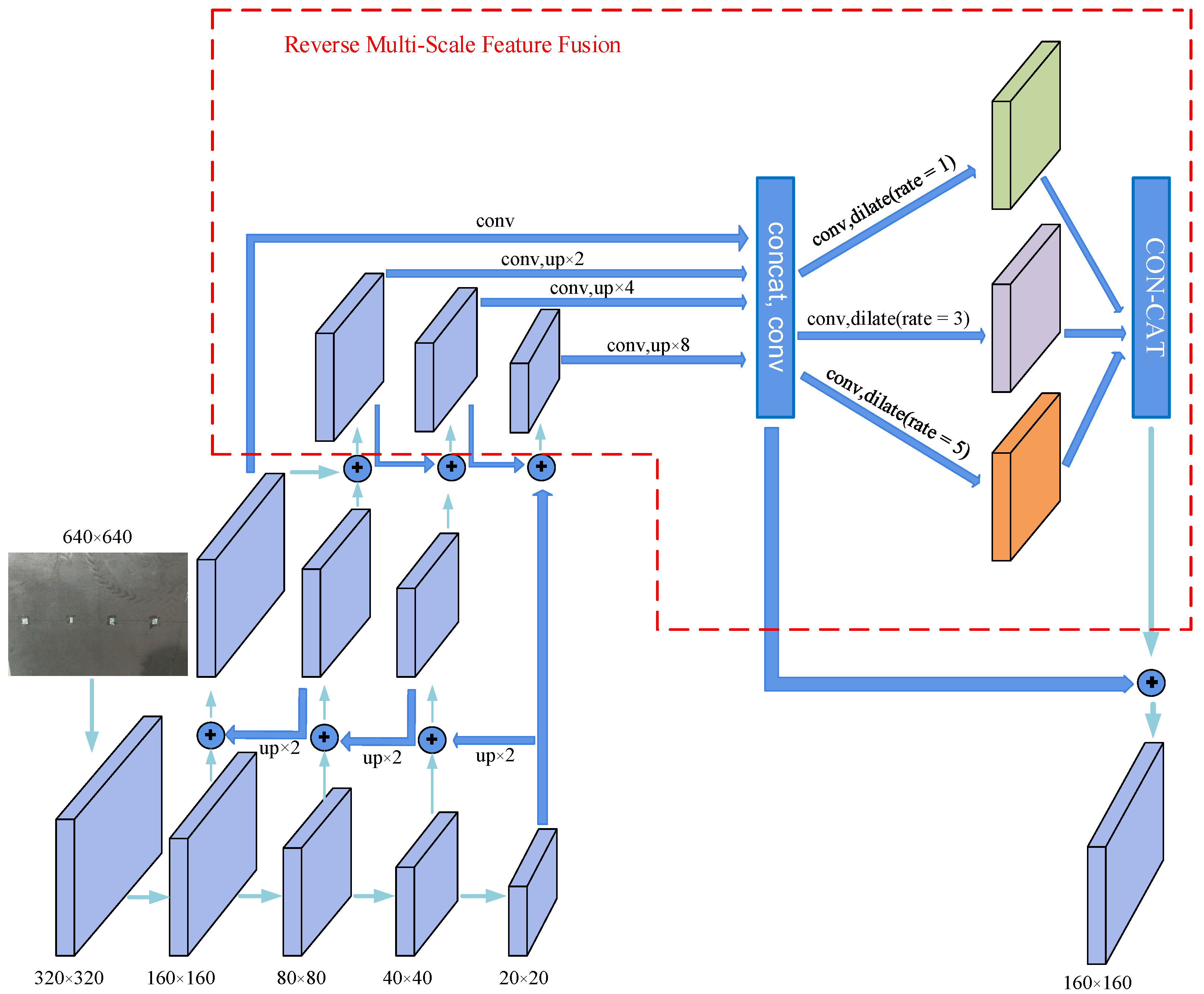

- Reverse Multi-Scale Feature Fusion

3.2.3. Performance Evaluation of the Improved Digital Stamp Detection Algorithm

3.2.4. The Method for Extracting the Weld Seam Parameters

- denote the radius of the pressure vessel;

- denote the weld path in the robotic arm base coordinate system.

- denote the coordinates of the weld path in the steel stamp coordinate system.

- is the radius of the receiver.

- denote the radius of the weld position parameter.

- denote transformation matrix from the weld path to the robotic arm base coordinate system.

4. Experiment and Results

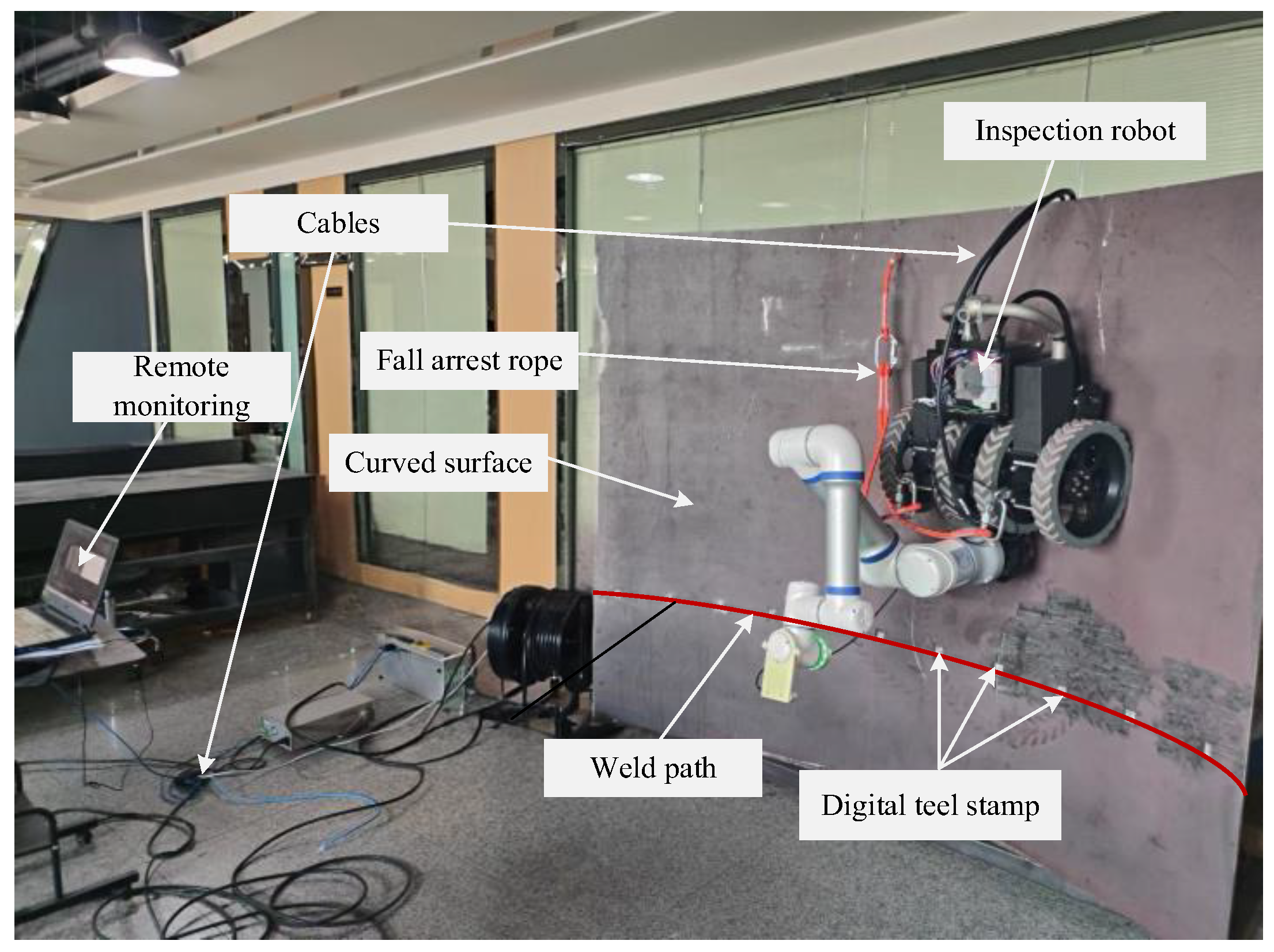

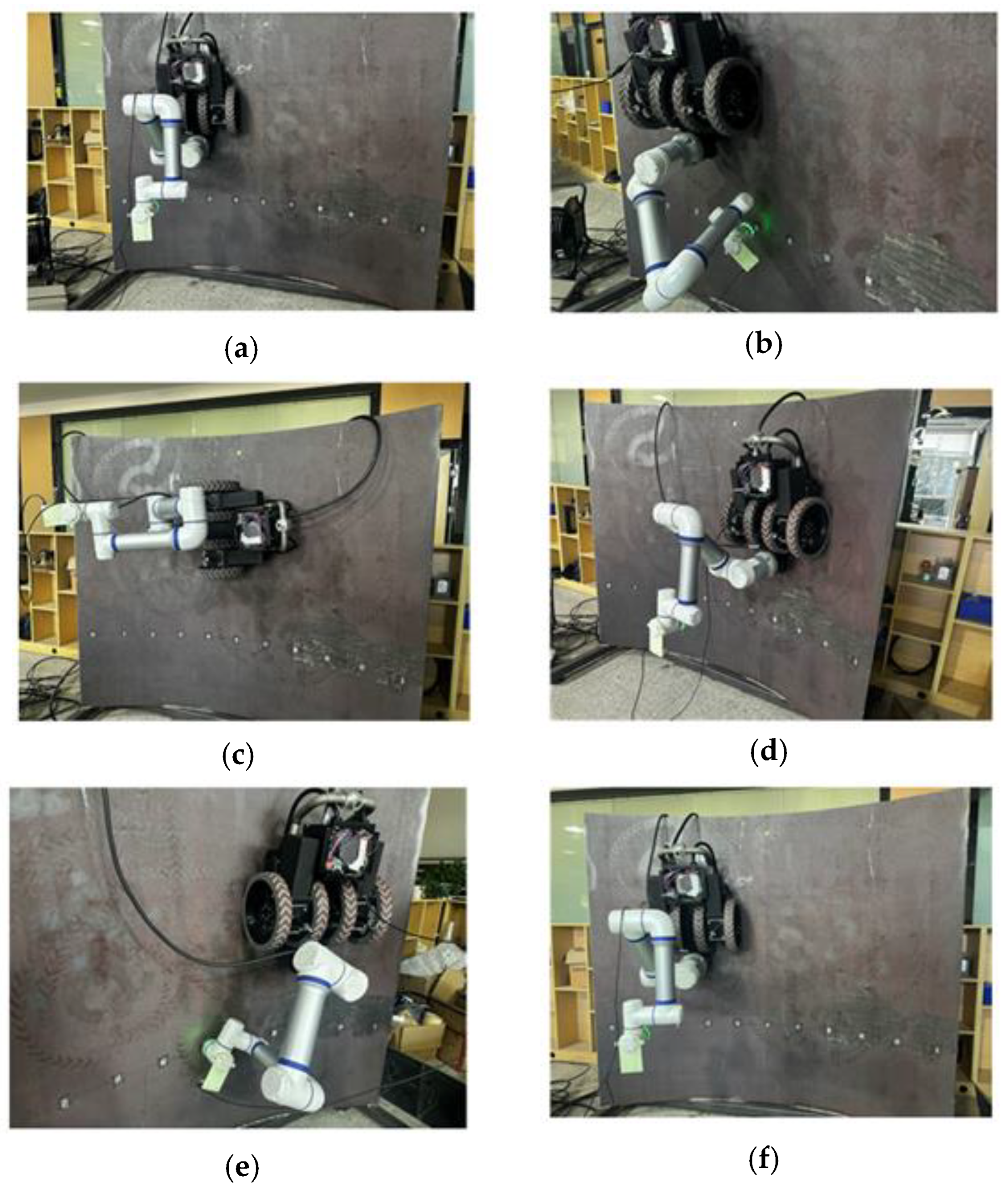

4.1. System Integration and Experimental Platform Construction

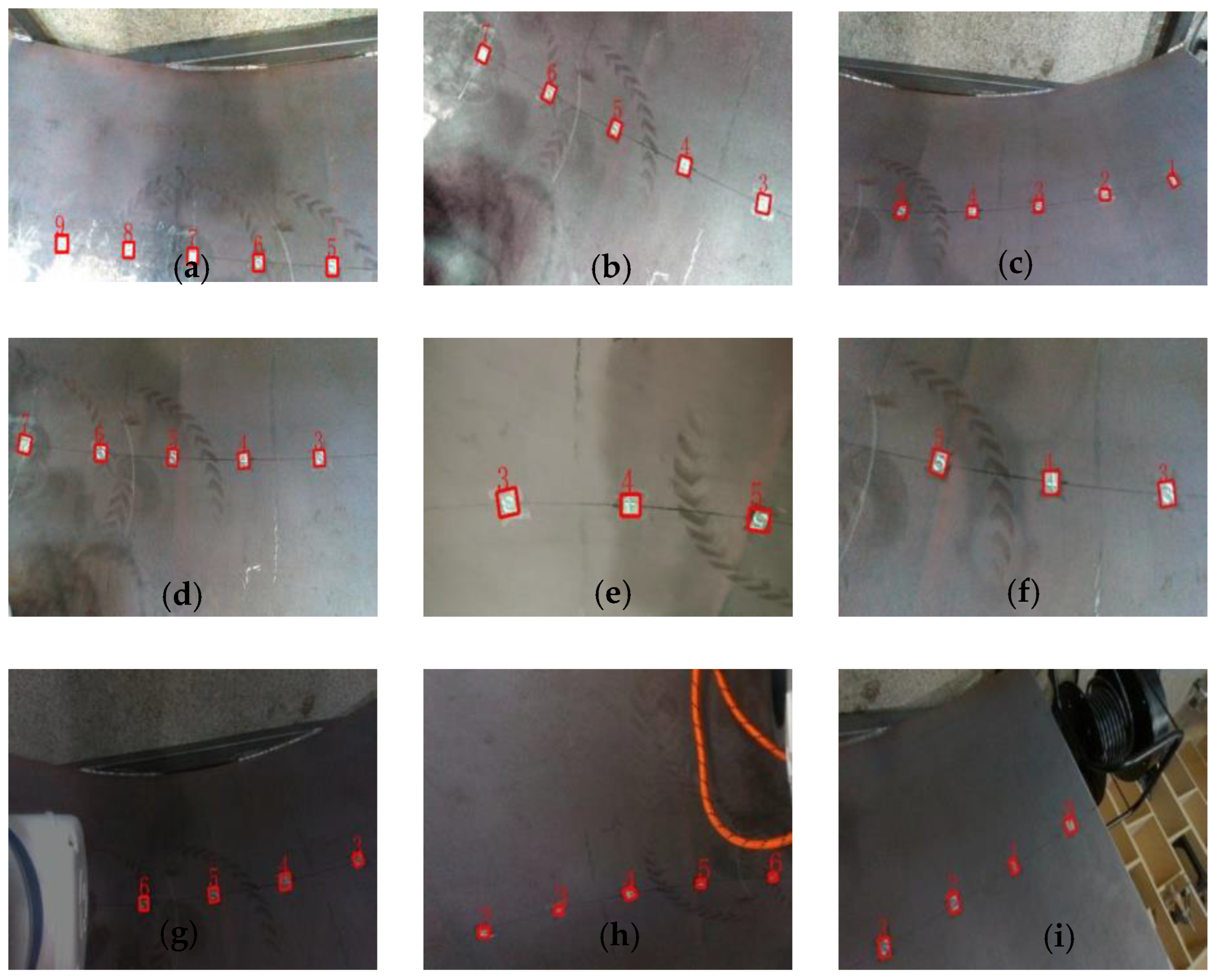

4.2. Weld Seam Stamp Detection and Positioning Experiment

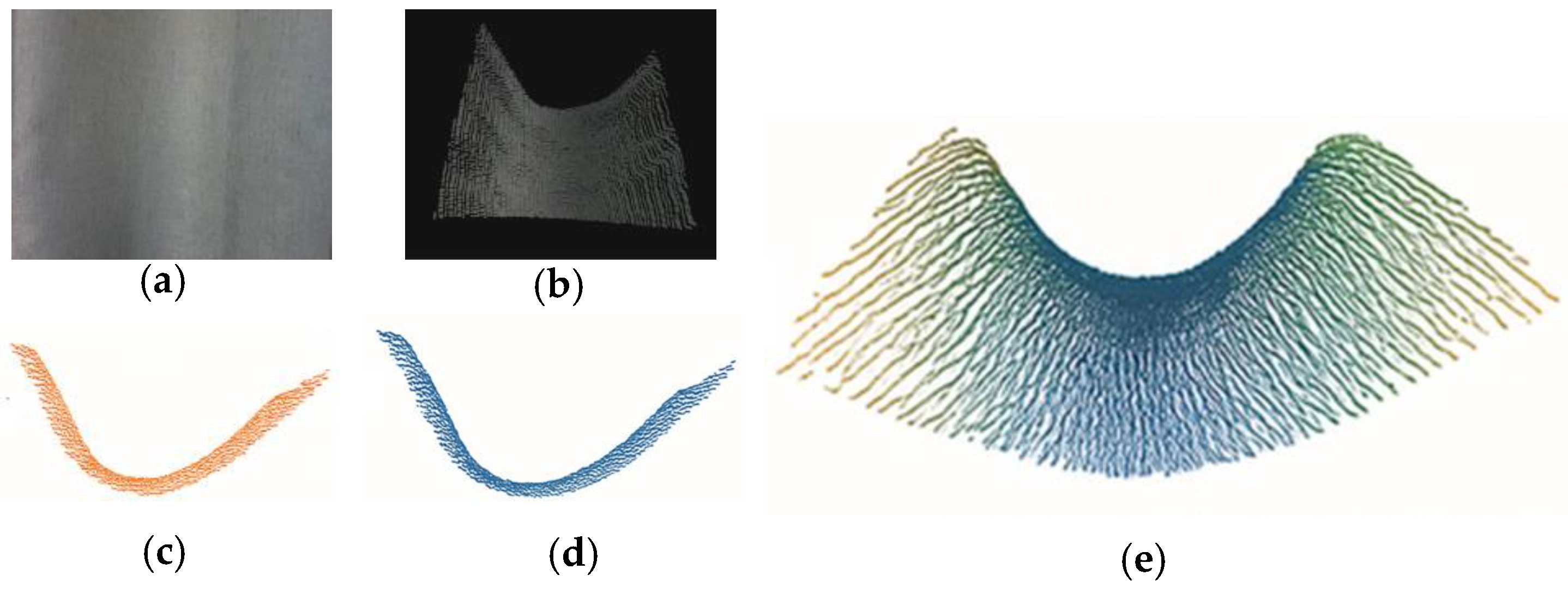

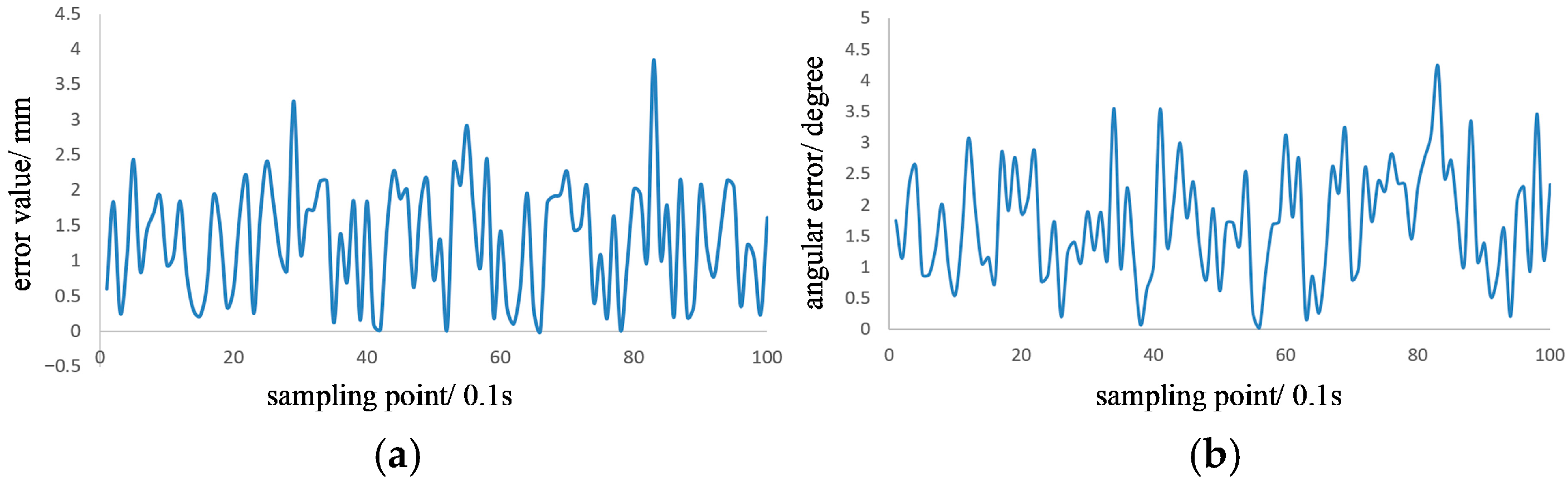

4.3. Weld Tracking Experiment

- represents the Euclidean distance error of the robotic arm tracking the weld;

- and represent the 3D coordinates recorded;

- denotes the weld surface normal vector;

- denotes the weld surface normal vector;

- denotes the deviation angle between and .

4.4. Weld Inspection Integral Traversal Experiment

- Chassis movement accounts for the largest portion of operation time. Robotic arm trajectory positioning, returning, and tracking consume similar durations, while detection and positioning require the least time. Increasing chassis speed could further improve efficiency.

- Detection leakage primarily occurs at the two ends of the weld, influenced by edge determination and positioning errors. This issue can be effectively mitigated in a complete weld structure.

- The robotic arm’s tracking speed of 96 mm/s complies with the ultrasonic flaw detection standard, which requires speeds below 150 mm/s.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ma, Y.; He, S.; Song, D.; He, X.; Chen, T.; Shen, F.; Baig, O.; Luo, S.; Wang, J. Crack propagation characteristics and fatigue life of the large austenitic stainless steel hydrogen storage pressure vessel. Int. J. Press. Vessel. Pip. 2024, 210, 105226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louis, H.K.; Ateya, A.A.E.; Amin, E. Evaluation of neutron radiation damage in the VVER-1200 reactor pressure vessel. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 2024, 221, 111738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Q.; Han, S.; Li, J.; Li, Y.; Li, J.; Yang, X. Research on the Application and Development of Intelligent Inspection System. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Information Technology, Big Data and Artificial Intelligence (ICIBA), Chongqing, China, 6–8 November 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, G.; Cheng, J. Advances in Climbing Robots for Vertical Structures in the Past Decade: A Review. Biomimetics 2023, 8, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.-H.; Lee, J.-C.; Choi, Y.-R. LAROB: Laser-Guided Underwater Mobile Robot for Reactor Vessel Inspection. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2014, 19, 1216–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, M.; Ikeda, S.; Fujimoto, T.; Shimizu, T.; Ikemoto, S.; Miyamoto, T. Development of universal vacuum gripper for wall-climbing robot. Adv. Robot. 2018, 32, 283–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šelek, A.; Seder, M.; Brezak, M.; Petrović, I. Smooth Complete Coverage Trajectory Planning Algorithm for a Nonholonomic Robot. Sensors 2022, 22, 9269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Govindaraju, M.; Fontanelli, D.; Kumar, S.S.; Pillai, A.S. Optimized Offline-Coverage Path Planning Algorithm for Multi-Robot for Weeding in Paddy Fields. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 109868–109884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fareh, R.; Baziyad, M.; Rabie, T.; Bettayeb, M. Enhancing Path Quality of Real-Time Path Planning Algorithms for Mobile Robots: A Sequential Linear Paths Approach. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 167090–167104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Zhao, J.; Pan, L.; Wu, X.; Hou, Y.; Qi, X. Optimal Path Planning for Mobile Robots in Complex Environments Based on the Gray Wolf Algorithm and Self-Powered Sensors. IEEE Sens. J. 2023, 23, 20756–20765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, R.; Jiang, Z.; Zhou, Q.; Wu, Y.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Jiang, Z. Online inspection of narrow overlap weld quality using two-stage convolution neural network image recognition. Mach. Vis. Appl. 2021, 32, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, B.; Dong, L.; Wang, X.; Tian, M. Weld Seam Identification and Tracking of Inspection Robot Based on Deep Learning Network. Drones 2022, 6, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Li, Q. The Algorithm of Watershed Color Image Segmentation Based on Morphological Gradient. Sensors 2022, 22, 8202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhruva, K.D.; Fang, C.; Zheng, Y.; Gao, Y. Semi-supervised transfer learning-based automatic weld defect detection and visual inspection. Eng. Struct. 2023, 292, 116580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Zhang, A.; Wang, P. Weld Cross-Section Profile Fitting and Geometric Dimension Measurement Method Based on Machine Vision. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 4455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Liu, M.; Wang, J.; Liu, X.; Wang, K.; Liu, Z.; Dong, Q.; Yao, J.; Lu, D.; Su, Y. A wall climbing robot based on machine vision for automatic welding seam inspection. Ocean. Eng. 2024, 310, 118825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Hu, P.; Gui, X.; Hua, L. An on-line weld inspection method for underwater offshore structure based on an improved deep convolutional network. Nondestruct. Test. Eval. 2025, 40, 289–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dometios, A.C.; Papageorgiou, X.S.; Arvanitakis, A.; Tzafestas, C.S.; Maragos, P. Real-time end-effector motion behavior planning approach using on-line point-cloud data towards a user adaptive assistive bath robot. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 24–28 September 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Papageorgiou, X.S.; Dometios, A.C.; Tzafestas, C.S. Towards a User Adaptive Assistive Robot: Learning from Demonstration Using Navigation Functions. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Prague, Czech Republic, 27 September–1 October 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Q.; Chen, D.; Wang, S.; Liu, S. Recognition Method for Handwritten Steel Billet Identification Number Based on Yolo Deep Convolutional Neural Network. In Proceedings of the 2020 Chinese Control and Decision Conference (CCDC), Hefei, China, 22–24 August 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Yang, G.; Wang, C.; Chang, G. Recognition of Casting Embossed Convex and Concave Characters Based on YOLO v5 for Different Distribution Conditions. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Wireless Communications and Mobile Computing (IWCMC), Harbin, China, 28 June–2 July 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X.; Yao, C.; Wen, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, S.; He, W.; Liang, J. EAST: An Efficient and Accurate Scene Text Detector. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, B.G.; Bai, X.; Yao, C. An End-to-End Trainable Neural Network for Image-Based Sequence Recognition and Its Application to Scene Text Recognition. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2017, 39, 2298–2304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiang, Y.-Y. Harvesting Geographic Features from Heterogeneous Raster Maps. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, USA, December 2010. [Google Scholar]

- He, Z.; Liu, C.; Chu, X.; Negenborn, R.R.; Wu, Q. Dynamic anti-collision A-star algorithm for multi-ship encounter situations. Appl. Ocean. Res. 2022, 118, 102995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Bai, A.; Wu, Y.; Yang, C.; Sun, H. DB-EAC and LSTR: DBnet based seal text detection and Lightweight Seal Text Recognition. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0301862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, M.; Liu, X.; Wang, K.; Liu, Z.; Dong, Q.; Wang, P.; Su, Y. Welding Seam Tracking and Inspection Robot Based on Improved YOLOv8s-Seg Model. Sensors 2024, 24, 4690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Planning Method | Path Length (m) | Overlapping Distance (m) | Maximum Steering Angle (°) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zigzag Coverage Algorithm | 41 | 5 | 90 |

| A* Algorithm | 32 | 2 | 60 |

| Algorithm | Path Length (m) | Number of Iterations | Execution Time (s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| RRT | 31.045 ± 1.423 | 186 ± 22 | 0.786 ± 0.112 |

| RRT* | 23.793 ± 1.151 | 199 ± 18 | 1.599 ± 0.159 |

| RRT-informed | 23.538 ± 0.947 | 169 ± 15 | 0.988 ± 0.083 |

| RRT-connect | 23.634 ± 0.915 | 194 ± 17 | 0.207 ± 0.041 |

| Detection Models | Precision (%) | Recall (%) | Detection Rate (fps) |

|---|---|---|---|

| TextBoxes++ | 87.7 | 85.8 | 5.7 |

| DBnet | 88.6 | 84.9 | 25.2 |

| EAST | 90.5 | 88.1 | 10.1 |

| Improved Algorithm | 94.7 | 90.2 | 21.6 |

| Number of Total Samples | Number of Valid Localizations | Error (mm) | Confidence Interval (95%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 167 | 160 | 1.13 ± 0.43 | [1.06, 1.20] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhong, M.; Pan, M.; Mao, Z.; Lyu, R.; Liu, Y. A Wall-Climbing Robot with a Mechanical Arm for Weld Inspection of Large Pressure Vessels. Actuators 2025, 14, 607. https://doi.org/10.3390/act14120607

Zhong M, Pan M, Mao Z, Lyu R, Liu Y. A Wall-Climbing Robot with a Mechanical Arm for Weld Inspection of Large Pressure Vessels. Actuators. 2025; 14(12):607. https://doi.org/10.3390/act14120607

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhong, Ming, Mingjian Pan, Zhengxiong Mao, Ruifei Lyu, and Yaxin Liu. 2025. "A Wall-Climbing Robot with a Mechanical Arm for Weld Inspection of Large Pressure Vessels" Actuators 14, no. 12: 607. https://doi.org/10.3390/act14120607

APA StyleZhong, M., Pan, M., Mao, Z., Lyu, R., & Liu, Y. (2025). A Wall-Climbing Robot with a Mechanical Arm for Weld Inspection of Large Pressure Vessels. Actuators, 14(12), 607. https://doi.org/10.3390/act14120607