Layered and Decoupled Calibration: A High-Precision Kinematic Identification for a 5-DOF Serial-Parallel Manipulator with Remote Drive

Abstract

1. Introduction

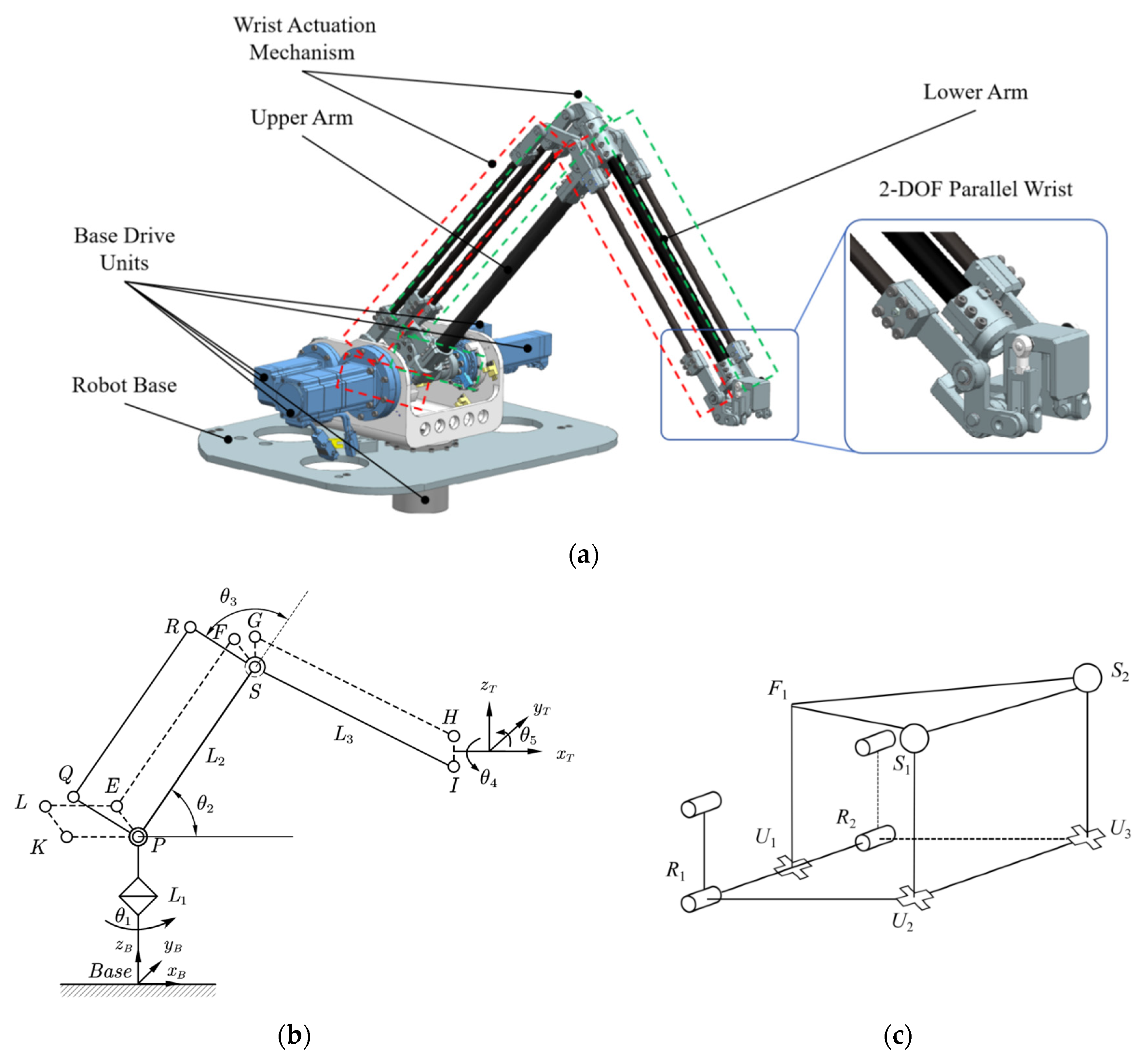

2. Configuration Design and Hierarchical Error Modeling

2.1. Configuration Design

2.2. Hierarchical Error Modeling

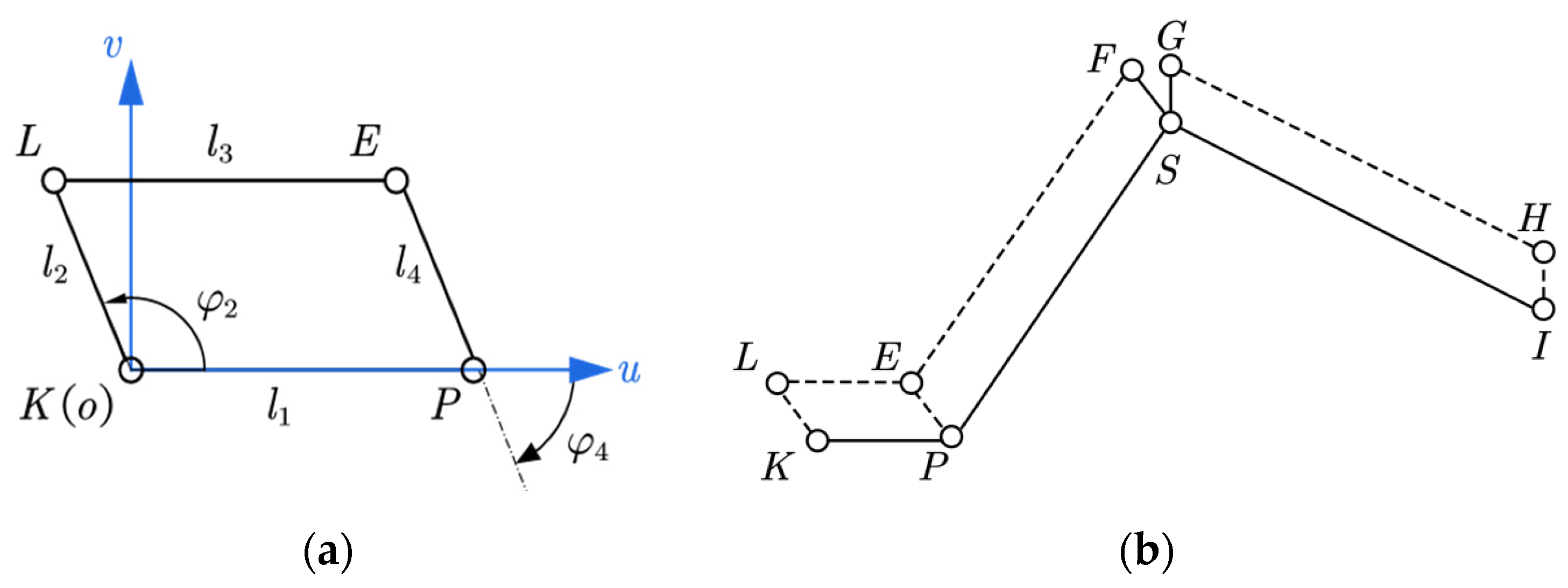

2.2.1. Error Modeling of Parallelogram Transmission

2.2.2. Error Kinematic Modeling of the 3-DOF Serial Main Arm

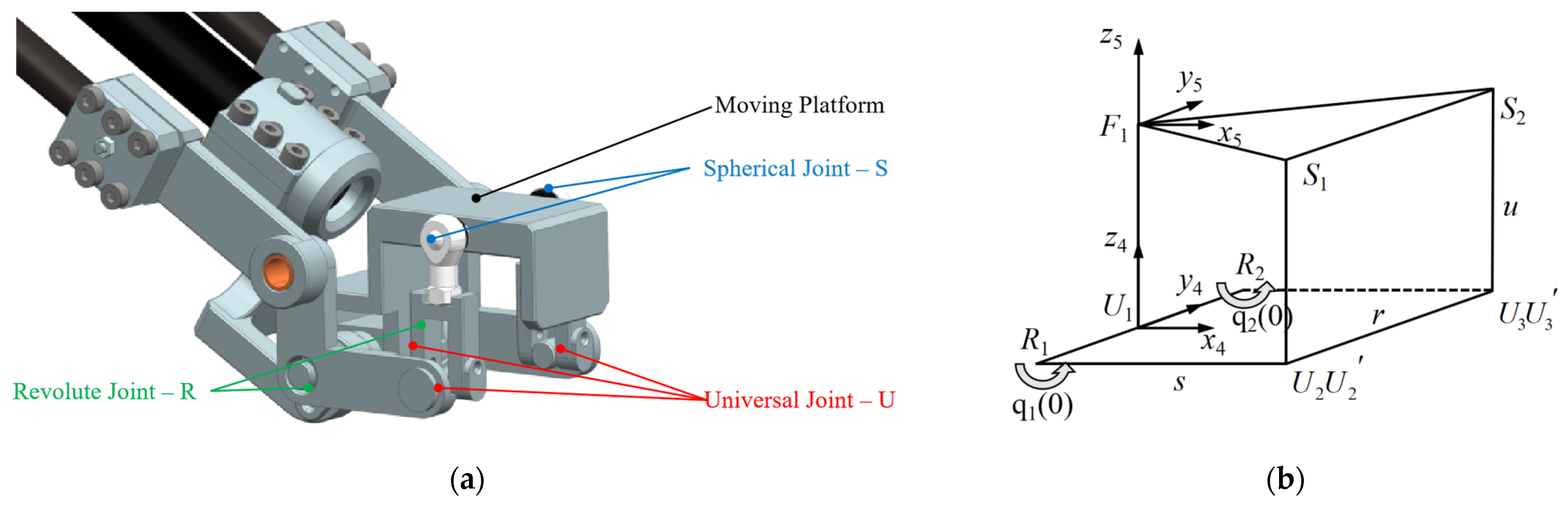

2.2.3. Error Kinematic Modeling of the 2-DOF Parallel Wrist

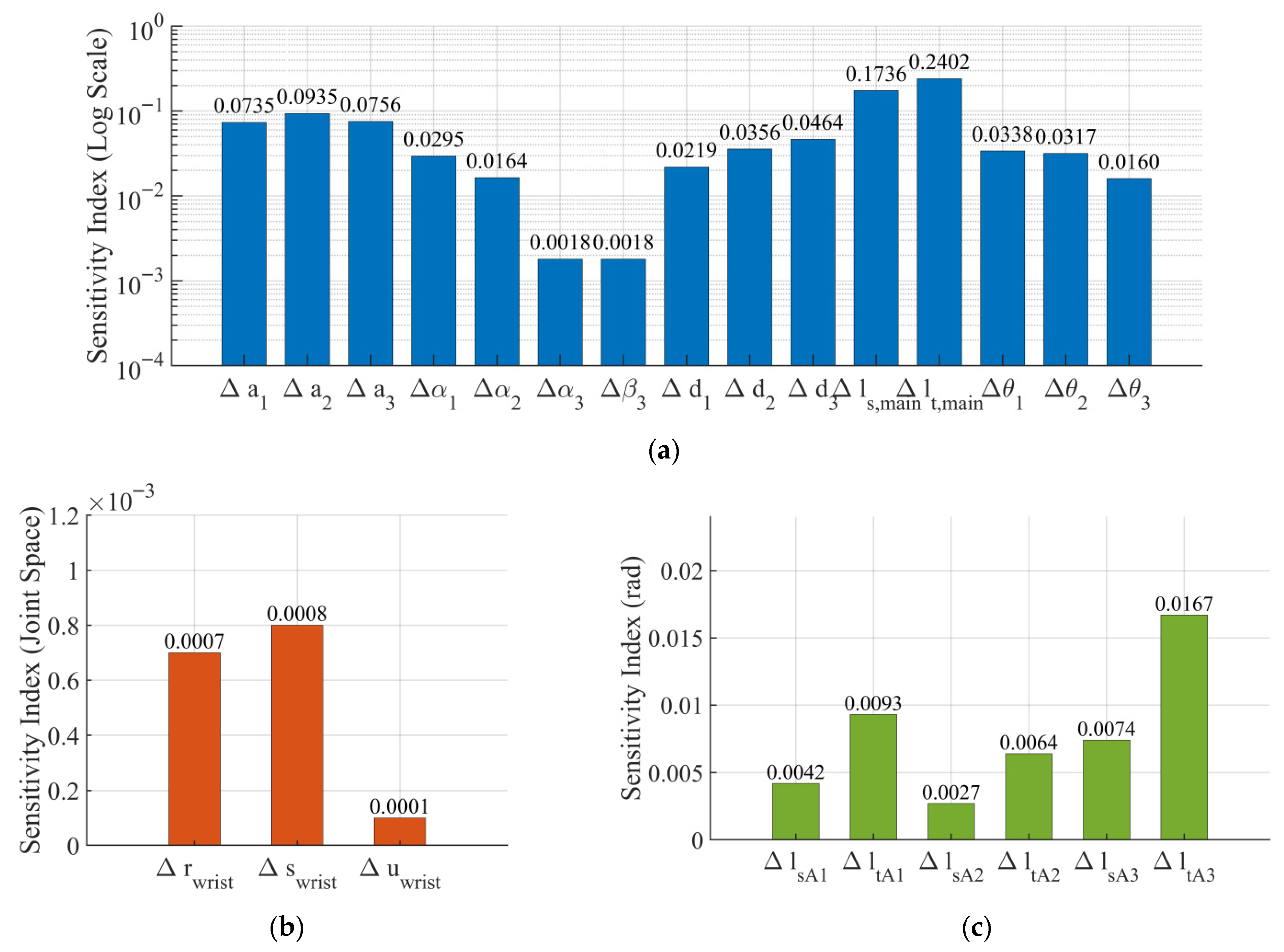

3. Sensitivity Analysis and Parameter Identification

4. Hierarchical Identification and Calibration

4.1. Pose Calibration of the 3-DOF Serial Main Arm

Baseline Comparison and Ablation Study (Serial Arm)

4.2. Calibration of the 2-DOF Parallel Wrist and Its Transmission Chain

- is the vector of error parameters to be identified for the parallel mechanism (, , ).

- is the vector of error parameters to be identified for the two transmission paths (, , , …).

- is the actual orientation angle (, ) of the -th point measured by the WIT sensor.

- is the actually measured angle of the actuated joints R1 and R2 corresponding to the -th orientation point.

- is the theoretical input angle of the parallel mechanism, calculated using the inverse kinematic error model from Equation (35), by substituting the measured orientation and the geometric parameters including errors, .

- is the theoretical output angle from the transmission chain, calculated using its error model by substituting the measured input angle and its error parameters .

Baseline Comparison and Ablation Study (Parallel Wrist)

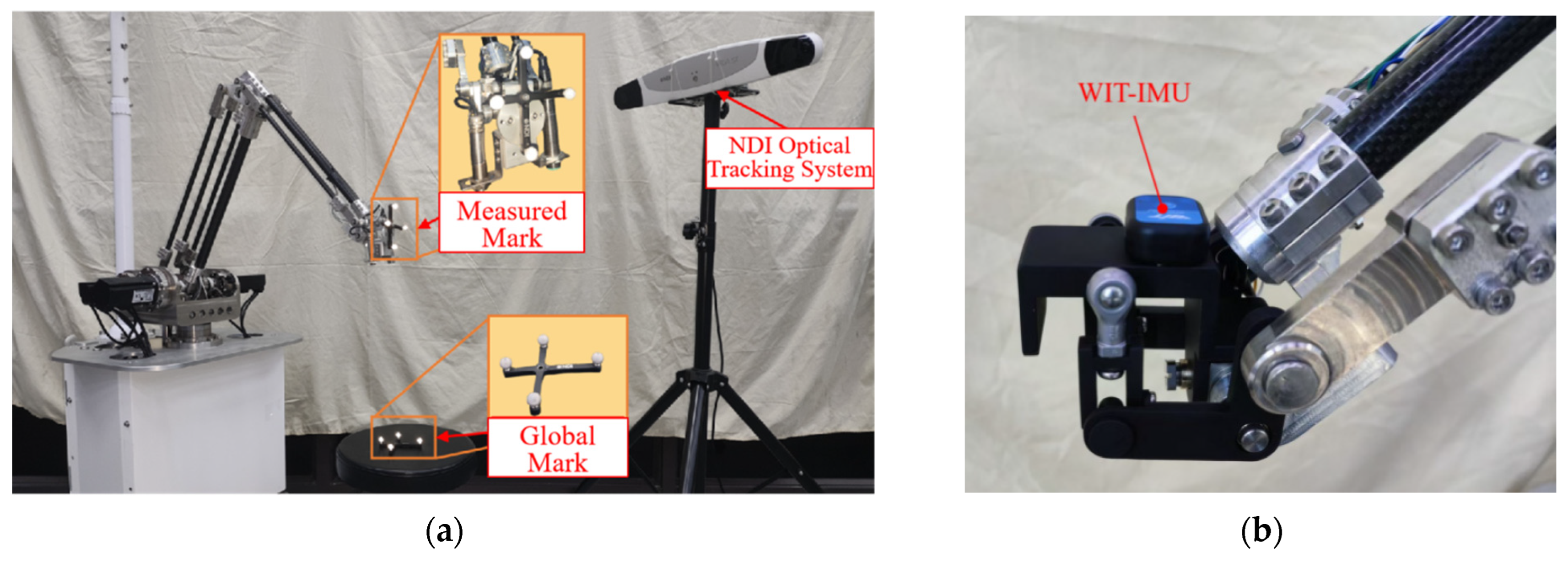

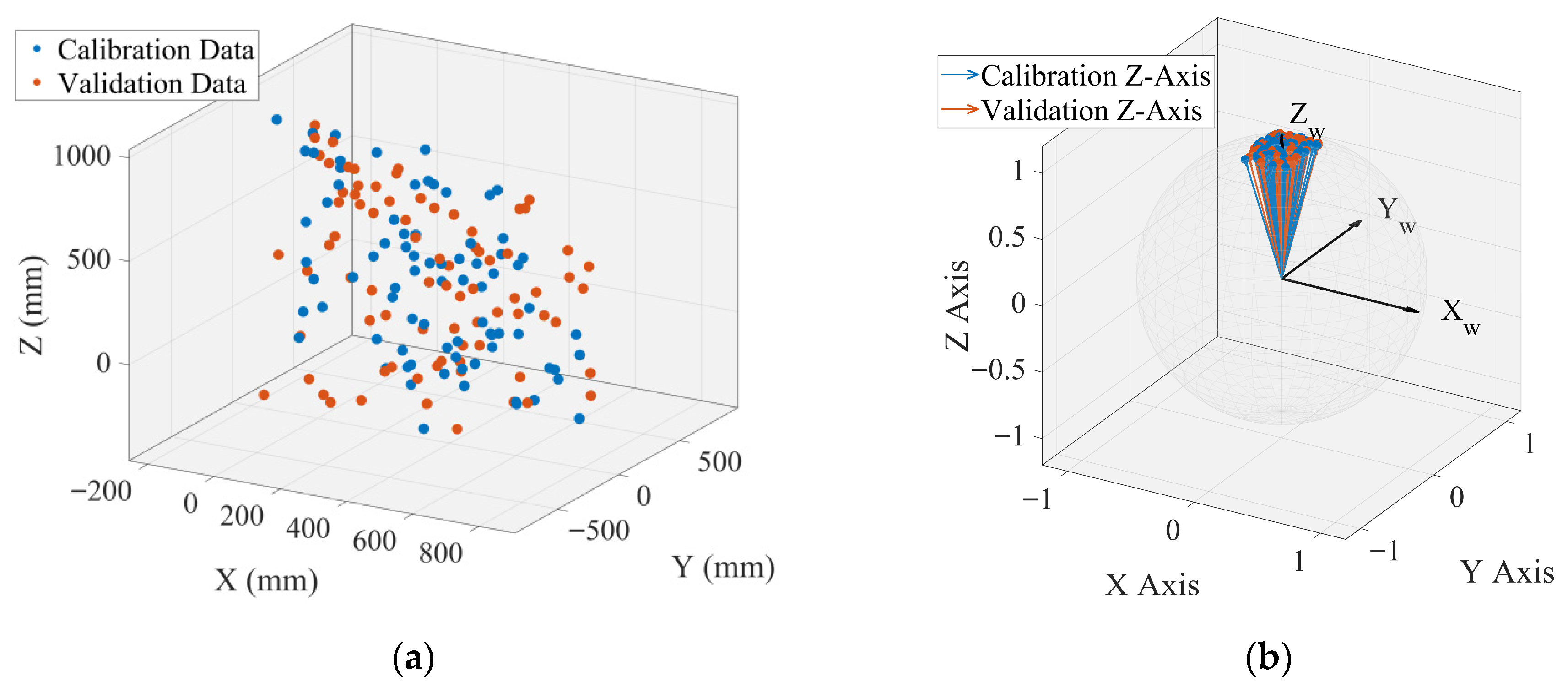

5. Calibration Experiment

6. Results and Discussion

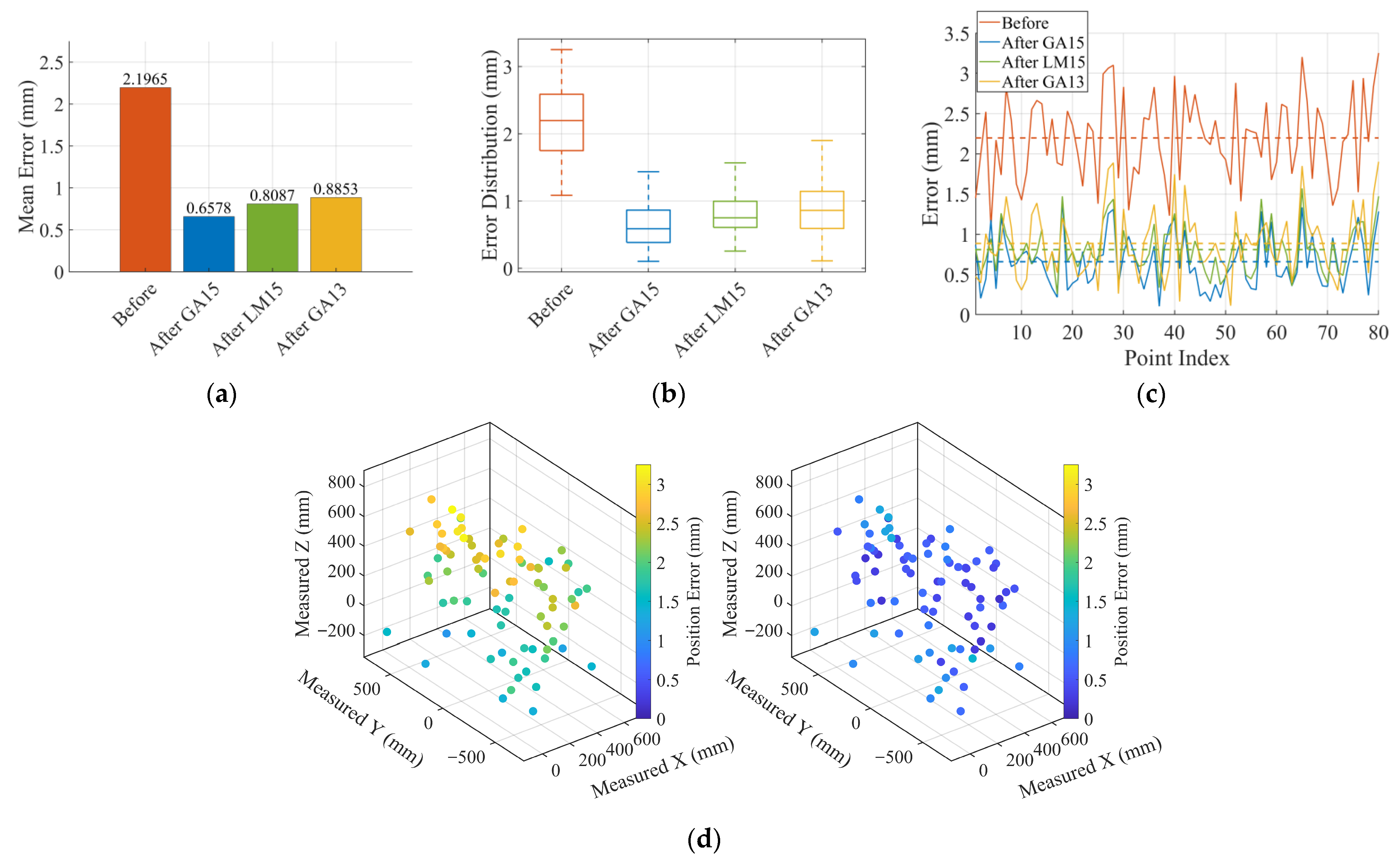

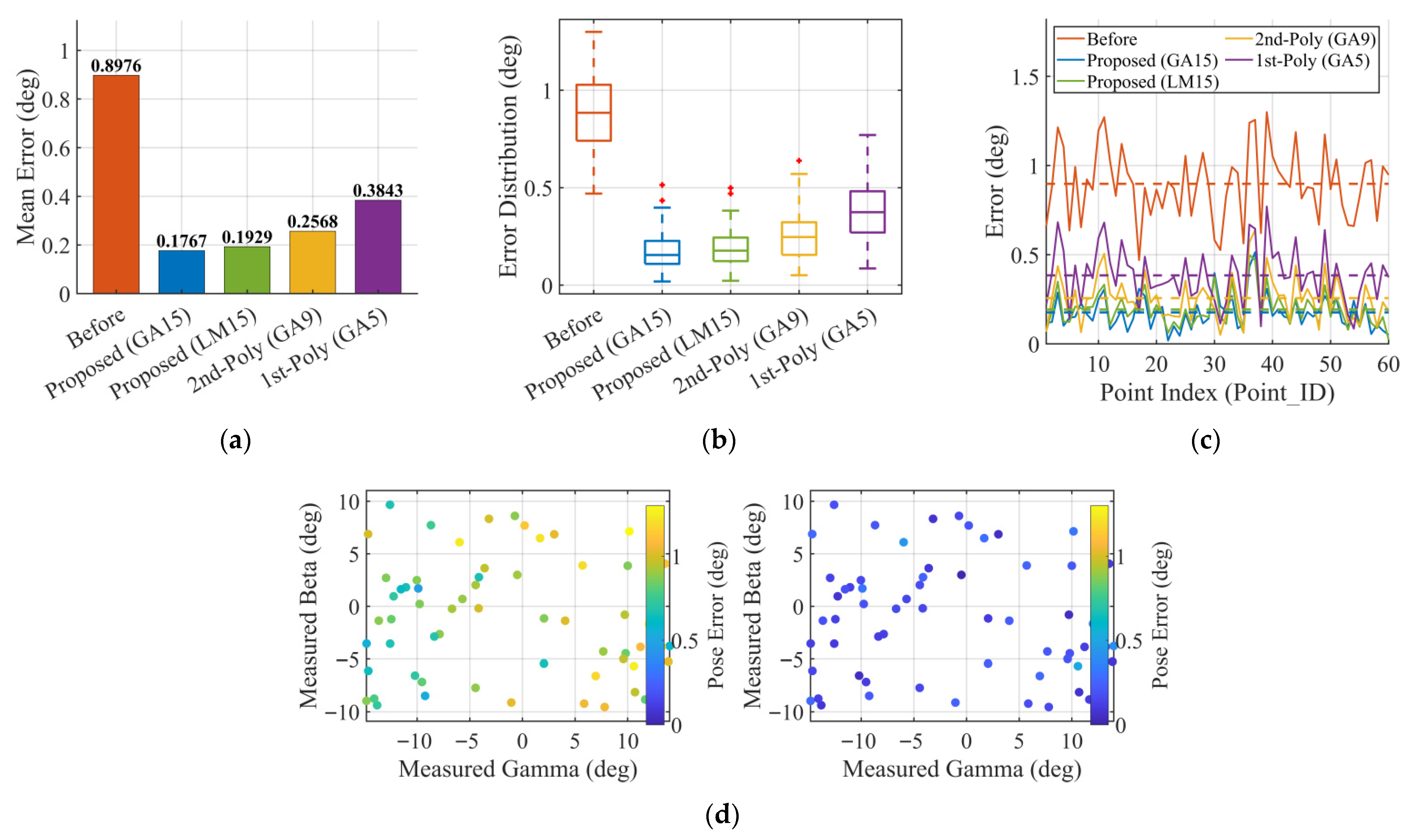

6.1. Serial Arm Calibration Results and Ablation Study

6.2. Serial Arm Robustness in Singular Region (Stress Test)

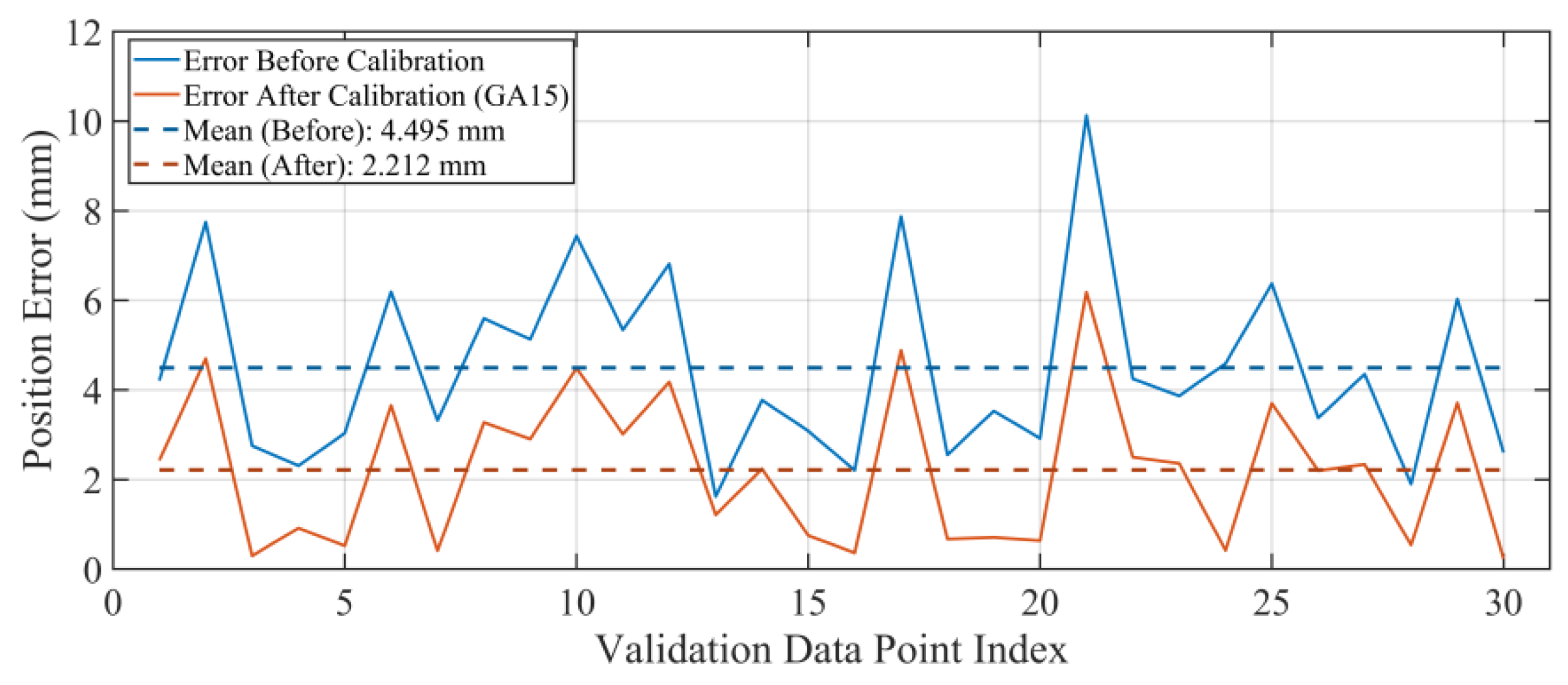

6.3. Parallel Wrist Calibration Results and Ablation Study

7. Conclusions and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, Y.L.; Guan, E.G.; Li, P.B.; Zhao, Y.Z. An automated nondestructive testing system for the surface of pressure pipeline welds. J. Field Robot. 2023, 40, 1927–1944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.S.; Yen, S.H.; Bedaka, A.K.; Shah, S.H.; Lin, C.Y. Trajectory planning method with grinding compensation strategy for robotic propeller blade sharpening application. J. Manuf. Process. 2023, 86, 294–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.H.; Wang, X.L.; Lyu, Z.K.; Xu, Q.S. Design of a Novel Passive Polishing End-Effector with Adjustable Constant Force and Wide Operating Angle. IEEE-ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2024, 29, 4330–4340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.C.; Liu, Y.L.; Wang, X.W.; Fang, S.K.; Liu, S.G. A new XR-based human-robot collaboration assembly system based on industrial metaverse. J. Manuf. Syst. 2024, 74, 949–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Li, Q.C. General methodology for type synthesis of symmetrical lower-mobility parallel manipulators and several novel manipulators. Int. J. Robot. Res. 2002, 21, 131–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merlet, J.-P. Parallel Robots; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Wu, C.; Liu, X.-J. Performance evaluation of parallel manipulators: Motion/force transmissibility and its index. Mech. Mach. Theory 2010, 45, 1462–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, A.; Mekid, S. Intelligent spherical joints based tri-actuated spatial parallel manipulator for precision applications. Robot. Comput.-Integr. Manuf. 2018, 54, 173–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, G.; Xu, P.; Yang, D.H.; Liu, H.G. Stiffness analysis of a 3CPS parallel manipulator for mirror active adjusting platform in segmented telescope. Robot. Comput.-Integr. Manuf. 2013, 29, 302–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.B.; Huang, P.C.; Li, Q.C. Modeling, design and experiment of a remote-center-of-motion parallel manipulator for needle insertion. Robot. Comput.-Integr. Manuf. 2018, 50, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.K.; Park, K.W.; Choi, B.O. Kinematic and dynamic models of hybrid robot manipulator for propeller grinding. J. Robot. Syst. 1999, 16, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonov, A.; Fomin, A.; Glazunov, V.; Kiselev, S.; Carbone, G. Inverse and forward kinematics and workspace analysis of a novel 5-DOF (3T2R) parallel-serial (hybrid) manipulator. Int. J. Adv. Robot. Syst. 2021, 18, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Cheung, C.F.; Li, B.; Ho, L.T.; Zhang, J.F. Kinematics analysis of a hybrid manipulator for computer controlled ultra-precision freeform polishing. Robot. Comput.-Integr. Manuf. 2017, 44, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.C.; Yu, Q.M.; Huang, K.; Mahov, S.; Eslami, A.; Maier, M.; Lohmann, C.P.; Navab, N.; Zapp, D.; Knoll, A.; et al. Towards Robotic-Assisted Subretinal Injection: A Hybrid Parallel-Serial Robot System Design and Preliminary Evaluation. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2020, 67, 6617–6628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Y.L.; Liao, C.C.; Chao, Z.G. Inverse kinematics for a novel hybrid parallel serial five-axis machine tool. Robot. Comput.-Integr. Manuf. 2018, 50, 63–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laryushkin, P.; Antonov, A.; Fomin, A.; Essomba, T. Velocity and Singularity Analysis of a 5-DOF (3T2R) Parallel-Serial (Hybrid) Manipulator. Machines 2022, 10, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonov, A.; Fomin, A.; Glazunov, V.; Petelin, D.; Filippov, G. Type Synthesis of 5-DOF Hybrid (Parallel-Serial) Manipulators Designed from Open Kinematic Chains. Robotics 2023, 12, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallardo-Alvarado, J. Kinematics of a hybrid manipulator by means of screw theory. Multibody Syst. Dyn. 2005, 14, 345–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Hu, B. Solving driving forces of 2(3-SPR) serial-parallel manipulator by CAD variation geometry approach. J. Mech. Des. 2006, 128, 1349–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Yu, J.J. Unified solving inverse dynamics of 6-DOF serial-parallel manipulators. Appl. Math. Model. 2015, 39, 4715–4732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boby, R.A.; Klimchik, A. Combination of geometric and parametric approaches for kinematic identification of an industrial robot. Robot. Comput.-Integr. Manuf. 2021, 71, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.P.; Meng, Q.M.; Li, J.; Deng, J.M.; Wu, G.L. Kinematic sensitivity, parameter identification and calibration of a non-fully symmetric parallel Delta robot. Mech. Mach. Theory 2021, 161, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho-Arreguin, J.; Wang, M.F.; Dong, X.; Axinte, D. A novel class of reconfigurable parallel kinematic manipulators: Concepts and Fourier-based singularity analysis. Mech. Mach. Theory 2020, 153, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbonari, L.; Callegari, M.; Palmieri, G.; Palpacelli, M.C. Analysis of Kinematics and Reconfigurability of a Spherical Parallel Manipulator. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2014, 30, 1541–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbonari, L.; Callegari, M.; Palmieri, G.; Palpacelli, M.C. A new class of reconfigurable parallel kinematic machines. Mech. Mach. Theory 2014, 79, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.Q.; Jin, Y.; Anderson, H.; Higgins, C. A new reconfigurable parallel mechanism using novel lockable joints for large scale manufacturing. Robot. Comput.-Integr. Manuf. 2023, 82, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, Z.S.; Mooring, B.W.; Ravani, B. An overview of robot calibration. IEEE J. Robot. Autom. 1987, 3, 377–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.H.; Zhou, W.G.; Li, H.; Mo, Y.; Ni, W.C.; Huang, Q. A New Kind of Accurate Calibration Method for Robotic Kinematic Parameters Based on the Extended Kalman and Particle Filter Algorithm. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2018, 65, 3337–3345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Klimchik, A.; Caro, S.; Furet, B.; Pashkevich, A. Geometric calibration of industrial robots using enhanced partial pose measurements and design of experiments. Robot. Comput.-Integr. Manuf. 2015, 35, 151–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.; Zhai, Y.P.; Song, Y.M.; Zhang, J.T. Kinematic calibration of a 3-DoF rotational parallel manipulator using laser tracker. Robot. Comput.-Integr. Manuf. 2016, 41, 78–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, G.Y.; Zou, L.; Wang, Z.L.; Lv, C.; Ou, J.; Huang, Y. A novel kinematic parameters calibration method for industrial robot based on Levenberg-Marquardt and Differential Evolution hybrid algorithm. Robot. Comput.-Integr. Manuf. 2021, 71, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denavit, J.; Hartenberg, R.S. A kinematic notation for lower-pair mechanisms based on matrices. J. Appl. Mech. 1955, 22, 215–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayati, S.; Mirmirani, M. Improving the absolute positioning accuracy of robot manipulators. J. Robot. Syst. 1985, 2, 397–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, H.; Roth, Z.S.; Hamano, F. A complete and parametrically continuous kinematic model for robot manipulators. IEEE Trans. Robot. Autom. 1992, 8, 451–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Yang, X.D.; Chen, K.; Ren, H.L. A Minimal POE-Based Model for Robotic Kinematic Calibration with Only Position Measurements. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2015, 12, 758–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, W.J.; Mou, M.W.; Yang, J.H.; Yin, F.W. Kinematic calibration of a 5-DOF hybrid kinematic machine tool by considering the ill-posed identification problem using regularisation method. Robot. Comput.-Integr. Manuf. 2019, 60, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.; Lian, B.B.; Yang, S.F.; Song, Y.M. Kinematic Calibration of Serial and Parallel Robots Based on Finite and Instantaneous Screw Theory. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2020, 36, 816–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Ding, Q.Y.; Gao, F.; Zhang, H.B. Kinematic calibration methodology of hybrid manipulator containing parallel topology with main limb. Measurement 2020, 152, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Codourey, A. Dynamic modelling and mass matrix evaluation of the DELTA parallel robot for axes decoupling control. In Proceedings of the 1996 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems—Robotic Intelligence Interacting with Dynamic Worlds (IROS 96), Senri Life Sci Ctr, Osaka, Japan, 4–8 November 1996; pp. 1211–1218. [Google Scholar]

- Ni, Y.B.; Jia, S.L.; Zhang, Z.W.; Wang, J.X.; Liu, X.; Li, J.H. A manufacturing-oriented error modelling method for a hybrid machine tool based on the 3-PRS parallel spindle head. Adv. Mech. Eng. 2019, 11, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.T.; Huang, T.; Chetwynd, D.G. A General Approach for Geometric Error Modeling of Lower Mobility Parallel Manipulators. J. Mech. Robot. 2011, 3, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joubair, A.; Bonev, I.A. Comparison of the efficiency of five observability indices for robot calibration. Mech. Mach. Theory 2013, 70, 254–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.L.; Wu, H.T.; Li, Y.; Chen, B. A dual quaternion solution to the forward kinematics of a class of six-DOF parallel robots with full or reductant actuation. Mech. Mach. Theory 2017, 107, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, D.M.; Dai, J.S.; Dias, J.; Seneviratne, L. Unified Kinematics and Singularity Analysis of a Metamorphic Parallel Mechanism with Bifurcated Motion. J. Mech. Robot. 2013, 5, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, C.; Zhao, G.L.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, L.; Sun, L.N. Calibration of a parallel mechanism in a serial-parallel polishing machine tool based on genetic algorithm. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2015, 81, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nubiola, A.; Bonev, I.A. Absolute robot calibration with a single telescoping ballbar. Precis. Eng.-J. Int. Soc. Precis. Eng. Nanotechnol. 2014, 38, 472–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laryushkin, P.; Fomin, A.; Antonov, A. Kinematic and singularity analysis of a 4-DOF Delta-type parallel robot. J. Braz. Soc. Mech. Sci. Eng. 2023, 45, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laryushkin, P.; Fomin, A.; Antonov, A.; Glazunov, V. Virtual and Physical Prototyping of the 4-DOF Delta-type Parallel Robot Based on the Criteria of Closeness to Singularity. In Proceedings of the MSR-RoManSy 2024, Combined IFToMM Symposium of RoManSy and USCToMM Symposium on Mechanical Systems and Robotics, Knoxville, TN, USA, 19–22 June 2024; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 167–178. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, C.; Guo, H.; Liu, R.; Deng, Z.; Li, B.; Tian, J. Actuation distribution and workspace analysis of a novel 3 (3RRlS) metamorphic serial-parallel manipulator for grasping space non-cooperative targets. Mech. Mach. Theory 2019, 139, 424–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.W.; Zhao, C.; Li, B.; Liu, R.Q.; Deng, Z.Q.; Tian, J. A Transformation Method to Generate the Workspace of an n(3RRS) Serial-Parallel Manipulator. J. Mech. Des. 2019, 141, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.T.; Yan, Z.B.; Xiao, J.L. Pose error prediction and real-time compensation of a 5-DOF hybrid robot. Mech. Mach. Theory 2022, 170, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Nominal Value | Parameter | Nominal Value | Parameter | Nominal Value | Parameter | Nominal Value | Parameter | Nominal Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 mm | 500 mm | 430 mm | 0° | s | 40 mm | ||||

| 90° | 0° | 90° | r | 42.5 mm | 74 mm | ||||

| 80 mm | 0 | 0 mm | 49 mm | 50 mm | |||||

| 100 mm | 74 mm | 24 mm |

| Order Number | Error | Tolerance | Order Number | Error | Tolerance | Order Number | Error | Tolerance | Order Number | Error | Tolerance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.115 mm | 7 | 0.062 | 13 | 0.2° | 19 | 0.074 mm | ||||

| 2 | 0.2° | 8 | 0.2° | 14 | 0.074 mm | 20 | 0.155 mm | ||||

| 3 | 0.037 mm | 9 | 0.155 mm | 15 | 0.155 mm | 21 | 0.074 mm | ||||

| 4 | 0.2° | 10 | 0.2° | 16 | 0.052 mm | 22 | 0.155 mm | ||||

| 5 | 0.155 mm | 11 | 0.074 mm | 17 | r | 0.062 mm | 23 | 0.074 mm | |||

| 6 | 0.2° | 12 | 0.2° | 18 | 0.062 mm | 24 | 0.155 mm |

| Serial Arm | Parameter | Identified Value | Parameter | Identified Value | Parameter | Identified Value | Parameter | Identified Value |

| 0.209 mm | 0.498° | 0.037 mm | 0.394° | |||||

| −0.179 mm | 0.420° | 0.739 mm | 0.420° | |||||

| 0.844 mm | - | 0.074 mm | 0.397° | |||||

| - | 0.0122 mm | −0.119 mm | ||||||

| Parallel Wrist | Parameter | Identified Value | Parameter | Identified Value | Parameter | Identified Value | Parameter | Identified Value |

| - | 0.025 mm | - | −0.003 mm | |||||

| 0.124 mm | 0.472 mm | −0.128 mm | 0.003 mm | |||||

| −0.308 mm | 0.166 mm | 0.309 mm | −0.315 mm | |||||

| −0.08 mm | r | 0.349 mm | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Chu, Y.; Wu, Y.; Mou, Y.; Wang, X.; Yang, H. Layered and Decoupled Calibration: A High-Precision Kinematic Identification for a 5-DOF Serial-Parallel Manipulator with Remote Drive. Actuators 2025, 14, 577. https://doi.org/10.3390/act14120577

Wang Z, Zhang J, Chu Y, Wu Y, Mou Y, Wang X, Yang H. Layered and Decoupled Calibration: A High-Precision Kinematic Identification for a 5-DOF Serial-Parallel Manipulator with Remote Drive. Actuators. 2025; 14(12):577. https://doi.org/10.3390/act14120577

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Zhisen, Juzhong Zhang, Yuyi Chu, Yuwen Wu, Yifan Mou, Xiang Wang, and Hongbo Yang. 2025. "Layered and Decoupled Calibration: A High-Precision Kinematic Identification for a 5-DOF Serial-Parallel Manipulator with Remote Drive" Actuators 14, no. 12: 577. https://doi.org/10.3390/act14120577

APA StyleWang, Z., Zhang, J., Chu, Y., Wu, Y., Mou, Y., Wang, X., & Yang, H. (2025). Layered and Decoupled Calibration: A High-Precision Kinematic Identification for a 5-DOF Serial-Parallel Manipulator with Remote Drive. Actuators, 14(12), 577. https://doi.org/10.3390/act14120577