1. Introduction

In recent years, the wet clutch has developed rapidly. The wet clutch has the advantages of high torque transmission capacity, a superior power-to-weight ratio, and the ability to tolerate high thermal loads. It is a core component of the vehicle transmission system.

During clutch disengagement, friction plates and steel plates experience relative rotation, which triggers viscous shearing of interposed lubricating oil, thereby producing drag torque. The existence of drag torque consumes engine power and reduces transmission efficiency; however, since lubrication is essential for wet clutches, this phenomenon is unavoidable. Experimental studies reveal that in a typical multi-speed automatic transmission, the power loss induced by clutch drag torque can account for up to approximately 20% of the total transmission power loss [

1]. This clearly demonstrates that minimizing drag torque is critically essential for enhancing transmission efficiency.

Clutches experience drag torque at both low and high speeds. For the low-speed segment, Xu et al. [

2] used the Volume of Fluid (VOF) model to determine the oil film contraction rates under various operating conditions. Building on these findings, a computational model for drag torque that incorporates oil film surface tension and contraction effects was established. Cho et al. [

3] demonstrated that friction plate groove designs with enhanced oil flowability increase the air content in clearance flow fields, thereby more effectively reducing drag torque. Subsequently, Hu and Yuan et al. [

4,

5] developed equivalent circumference angle and equivalent oil film radius models to characterize the relationship between gas–liquid two-phase flow and rotational speed, with experimental validation. By implementing CFD technology, Pardeshi et al. [

6] established a computational model for drag torque that accounts for air compressibility and contact angle effects, improving prediction accuracy. Cui et al. [

7,

8] derived an oil temperature calculation formula through experimental investigations and response surface methodology (RSM), then determined the actual lubricant viscosity using viscosity-temperature equations, thereby refining wet clutch drag torque modeling. Although the gas content-dependent model proposed by Iqbal et al. [

9,

10] better reflects actual wet clutch operating conditions, its prediction accuracy requires further enhancement due to the absence of viscosity equations correlating with gas concentration. Furthermore, Goszczak et al. [

11] experimentally validated that viscous shear of oil films dominates drag torque generation in the low-speed regime. As rotational speed increases, oil film rupture initiates, leading to progressive enhancement of oil–air two-phase flow and cavitation effects, which induces a significant transition in drag torque behavior. This phenomenon aligns with Pointner-Gabriel et al.’s [

12] mechanistic summary of drag torque governing mechanisms across low- and high-speed operational domains.

For high-speed drag torque issues, Mantwill [

13] experimentally investigated drag torque in high-speed clutches. The results demonstrated that when rotational speed exceeds a critical threshold, touching vibration occurs between friction pairs, causing an abrupt surge in drag torque. Peng et al. [

14] developed a three-degree-of-freedom angular swing self-excited vibration model for friction plates in high-speed single-plate wet clutches. The study revealed weak coupling between axial and angular vibrations, allowing the motion to be decoupled into two independent modes for separate analysis. Hou et al. [

15] experimentally discovered that unstable oscillations of friction plates are a critical contributor to abrupt surges in drag torque. Zhang et al. [

16] proposed a high-speed drag torque model incorporating the actual clearance distribution of clutch friction pairs, which demonstrates superior predictive performance through experimental validation. Concurrently, Rogkas et al. [

17] established a unified modeling methodology encompassing hydrodynamic, mixed, and boundary lubrication regimes. Although primarily focused on clutch engagement dynamics, this approach provides valuable insights for developing integrated drag torque models across wide-speed domains. Pointner-Gabriel et al. [

18] experimentally validated the variation of drag torque under diverse oil levels and rotational speeds, achieving real-time process visualization that furnishes critical experimental underpinnings for comprehensive drag torque modeling in the wide-speed domain.

Regarding drag torque suppression in wet clutches, current research primarily focuses on the influence of groove geometry parameters. Xiang et al. [

19] investigated groove depth, groove ratio, and groove count effects, revealing that drag torque exhibits a negative correlation with these parameters. Cheng et al. [

20] modified groove angle configurations to study oil–air two-phase flow interactions, demonstrating that negative groove angles enhance drag torque reduction. Hu et al. [

21] utilized single-plate clutch testing to examine fluid behaviors and groove profiles, identifying spiral grooves as significantly affecting drag torque. In summary, a methodological void persists within the current research landscape regarding optimized drag torque suppression across broad operating speed ranges in wet clutches. International scholars have concurrently advanced this domain, with Neuper et al. [

22] employing CFD simulations to elucidate the impact of divergent groove geometries on flow field behavior and drag torque characteristics. Experimental validation further corroborated the reliability of their computational fluid dynamics methodology. Groetsch et al. [

23] systematically compared the Singhal cavitation model and the VOF method’s computational outcomes across varying groove width configurations. Their findings conclusively demonstrate that the groove architecture directly governs the magnitude of drag torque generation.

In summary, current research on wet clutch drag torque predominantly focuses exclusively on either low-speed or high-speed regimes, lacking a unified predictive model applicable across broad operating speed ranges.

Furthermore, contemporary research on drag torque suppression methodologies remains distinctly bifurcated into investigations targeting either low-speed or high-speed regimes, with critically insufficient attention paid to approaches spanning broad operational speed ranges. Although international progress has been made in groove optimization, it is still confined to a certain speed range and lacks unified suppression strategies for wide speed ranges. Based on this, the paper formulates a unified drag torque model applicable across wide-speed ranges, with its predictive accuracy rigorously validated through experimental investigations. Furthermore, parametric modeling of generalized curve geometries is implemented to establish an optimal design framework for clutch friction pairs. This integrated methodology ultimately achieves comprehensive drag torque reduction throughout the entire speed spectrum in wet clutches, substantiated by experimental verification protocols.

2. A Generalized Drag Torque Model for Unloaded Wet Clutches in Full-Spectrum Rotational Speed Conditions

2.1. Low-Speed Drag Torque Model

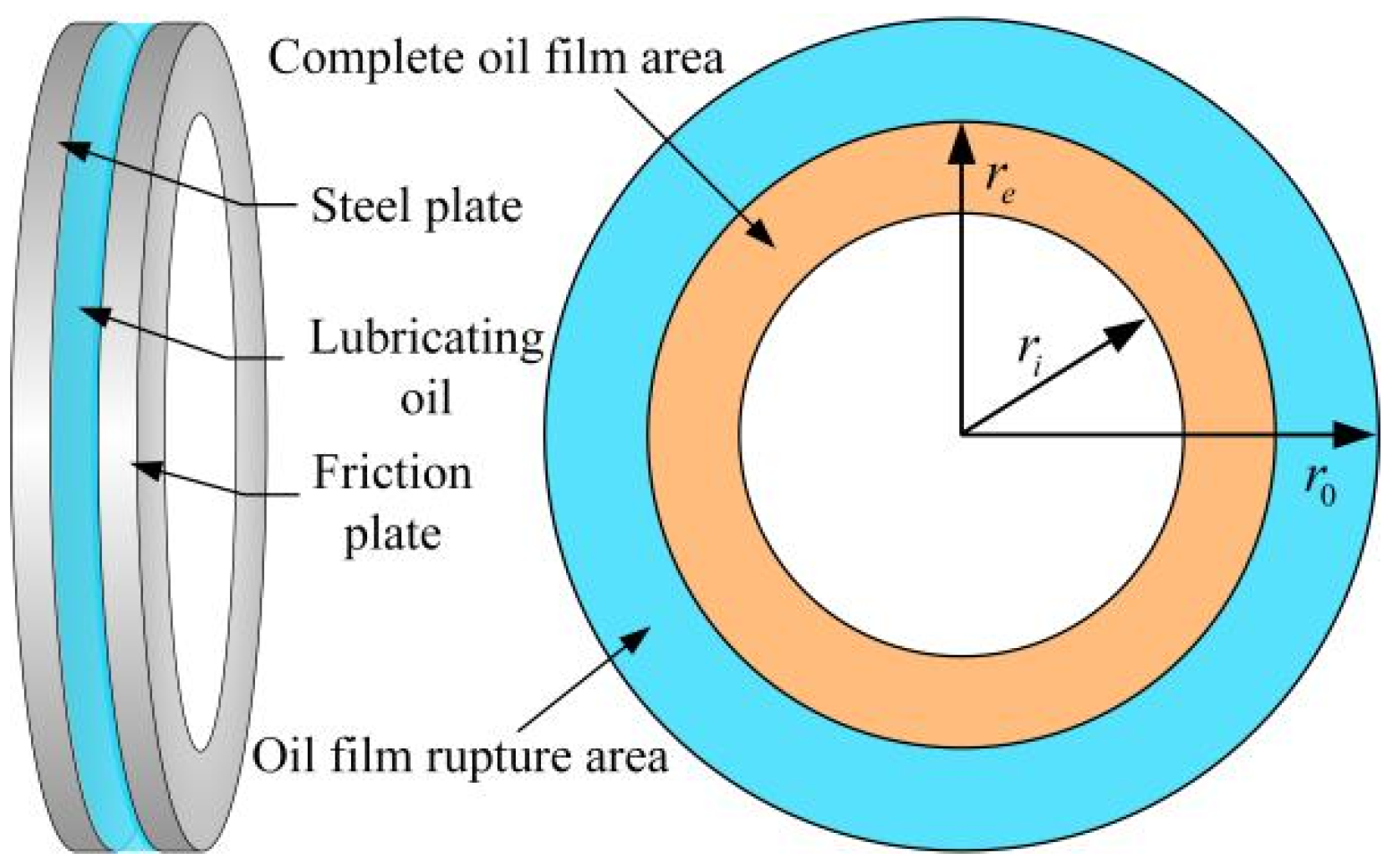

Through analysis of clearance flow field evolution, traditional drag torque modeling adopts distinct approaches separated by a critical rotational speed triggering oil film rupture. The full-film drag torque model applies prior to rupture onset. Post-rupture modeling introduces a homogeneous mixture assumption throughout the friction pair clearance, considering the domain entirely occupied by oil–gas two-phase flow, thereby establishing a two-phase drag torque prediction framework based on this fundamental assumption. In physical reality, oil film rupture originates at the outer diameter of the friction pair clearance. With increasing operating speeds, the rupture radius progressively contracts inwardly. Consequently, annular regions beyond this radius transition into oil–gas two-phase flow, while interior areas maintain full-film conditions. The fluid flow distribution within the friction pair clearance gap is shown in

Figure 1.

This spatial demarcation partitions the clearance flow field into two distinct domains: a continuous oil film region and a two-phase flow region. This study consequently develops a novel low-speed drag torque model that includes the friction torque of the oil film region and the oil-gas two-phase flow.

2.1.1. Oil Film Rupture Radius

Within the clearance gap of the friction pair, the operating flow rate is derived from the circumferential integral of the radial velocity component. Since the radial velocity demonstrably increases with rotational speed, this confirms that the clutch’s operating flow rate must monotonically increase with friction pair rotational speed. However, the actual operating flow rate is constrained by the oil supply system and does not increase with clutch rotational speed. When the theoretically calculated flow rate exceeds the actual supply flow rate, the working fluid fails to fully fill the friction pair clearance gap. Consequently, oil film rupture initiates at the outer diameter of the clearance gap, with the rupture radius progressing radially inward as rotational speed increases.

Defining

ri,

ro, and

re,

ro as the inner diameter, oil–film rupture radius, and outer diameter of the friction pair respectively, the Navier-Stokes equations in cylindrical coordinates for the clearance flow field are formulated as follows:

In the formula,

µf represents viscosity of the lubricant;

ρ represents density;

ur represents radial velocity component;

uθ represents circumferential velocity component; and

z represents coordinate axis normal to the clearance thickness. Considering the no-slip boundary condition for fluid velocity at the wall surface, the radial velocity equation of the lubricating oil can be derived from the equation above.

In the formula,

ω1 represents rotational speed of the separator plate;

ω2 represents rotational speed of the friction plate; and

h represents clearance of the friction pair. Subsequently, the expression for the inlet flow rate

Q at the inner radius of the friction pair clearance can be obtained from the radial velocity:

Substituting the radial fluid velocity expression (3) into Equation (4) and rearranging yields provides the following:

Therefore, given the actual oil supply flow rate (inlet flow rate)

Q, integrating the above equation along the radial direction yields the pressure at any radius

r within the full-film lubrication region under actual flow conditions.

In the formula,

p(

ri) represents oil pressure at the inner radius of the friction pair clearance. Consequently, the oil pressure on the inner side of the oil–air interface at oil film radius

re satisfies the following:

Considering the effect of oil surface tension, a pressure difference caused by tension exists at the oil–air interface of rupture radius

re, which is represented as follows:

In the formula,

σ represents surface tension coefficient of the oil;

kz represents curvature along the z-direction of the oil-air interface; and

θ represents contact angle of the oil on the friction material surface. Finally, substituting Equation (7) into Equation (8) gives the following:

The equivalent rupture radius re can be determined by solving the preceding equation system.

2.1.2. Oil–Film-Zone’s Drag Torque

The oil–film rupture radius redivides the friction pair clearance into two regions: an oil–film-zone and an oil–air two-phase flow zone. Within the oil–film-zone, where a complete lubricating oil film is maintained, the friction torque caused by viscous shearing is given by the following:

In the formula,

τzθ represents shear stress of the lubricating oil. According to Newton’s law of fluid friction,

In the formula,

µoil represents viscosity of lubricating oil and

represents shear strain rate of the lubricating oil. Substituting the above expression into Equation (10), the viscous friction torque generated by the lubricating oil is given as follows:

In the formula, the viscous drag torque in the full-film lubrication region exhibits a positive correlation with lubricant viscosity. An increase in lubricant viscosity consequently amplifies the drag torque magnitude within this regime, as governed by Newton’s law of fluid friction.

2.1.3. Drag Torque in Gas–Liquid Two-Phase Flow Region

The oil–film rupture region is defined as the region from the oil film rupture radius

re to the outer diameter of the friction pair

ro, wherein the lubricant exists in an atomized state of oil–air two-phase mixture. It is postulated that the viscosity remains uniform at any given radius within the oil–air two-phase flow zone. The viscosity at a given radius is composed of air viscosity and liquid-phase viscosity mixed at specific constitutive proportions, with the expression given as follows:

In the formula,

φair represents air volume fraction, satisfying 0 ≤

φair ≤ 1. When the volume fraction equals 0, the flow field is deemed to be completely filled with oil; conversely, when it equals 1, the flow domain is entirely comprised of air. The air volume fraction represents the ratio of the air-phase flow rate to the theoretical flow rate (

Qr) in the two-phase flow region. Here, the theoretical flow rate

Qr corresponds to the flow rate theoretically required when the friction pair clearance operates under a full oil-film condition, with its expression derived by differentiating Equation (6) with respect to radius, substituting into Equation (5), and subsequently rearranging, as follows:

The expression for the air volume fraction is given by

Within oil–air two-phase flow domains, the drag torque is attributed to viscous shear friction coupling effects at oil–air interfaces. Accordingly, in accordance with Newton’s law of viscosity, the generalized drag torque formulation for multiphase flow zones is expressed as

In the formula, mixed viscosity persists as a dominant contributor to drag torque generation. As analytically established in Equation (13), the mixed viscosity in oil–air mediums fundamentally relies on the base lubricant viscosity. Consequently, elevated temperatures reduce lubricant viscosity, which directly diminishes the mixed-phase viscosity, resulting in drag torque attenuation within the two-phase flow region.

2.2. High Rotational Speed Drag Torque Modeling Framework

As clutch operation rotational speed increases, frictional collisions develop at friction–plate or steel–plate interfaces, triggering a dramatic surge in drag torque. To facilitate analysis, a solitary friction plate is modeled. Under clutch separation conditions, the adjacent steel separator plates remain stationary in position. The friction plate undergoes axial displacement along the z-axis while executing angular oscillations about the x-axis and y-axis orthogonal to the rotational axis. Subject to interfacial fluid–elastic forces or moments, damping loads, inertial couplings, and axial excitations within bilateral gap flow fields, the friction disc exhibits coupled triaxial motion. The dynamic analysis of wet clutch friction pair is shown in

Figure 2.

This justifies constructing a fluid–structure interaction (FSI) dynamic model:

In the formula, z, α, and β represent the axial displacement along the z-axis and the angular displacements (tilt angles) about the x-axes and y-axes for the friction disc.

The primary term on the left-hand side represents the inertial operator, m represents the mass of the friction disc, Ix represents the moment of inertia about the x-axis, Iy represents the moment of inertia about the y-axis, and , , and represent axial acceleration and angular acceleration.

The second term on the left-hand side represents the elastic contributions of the fluid within the friction pair clearance, formulated as the dot product of the fluid stiffness coefficient matrix kij and the displacement vector of the friction disc. The indices i and j assume values from the set {z, α, β}. When i = j, the term denotes the direct stiffness along the i-direction; when i ≠ j, it represents the cross-coupling stiffness between the i-directions and j-directions.

The third term on the left-hand side represents the fluid damping component, which is expressed as the product of the continuous viscous damping coefficient matrix

cij and the motion velocity vector of the friction plates [

24]. The diagonal elements (

i =

j) denote the

i-directional direct damping coefficients, whereas the off-diagonal terms (

i ≠

j) represent the cross-directional damping between the

i-axes and

j-axes. The right-hand side of the equation comprises the external force or moment components acting on the friction plates, incorporating both the impact-induced coupling component from friction pair interaction and the gyroscopic moment component, which could be determined by the collision force equation and the rotational moment equation of the friction pair.

2.2.1. Friction Pair Collision Force Dynamics Formulation

The collision force between the steel plate and the friction plate of the friction pair exhibits a clear correlation with the gradual dynamics of contact deformation during impact events. Herein, based on the contact deformation amount, the widely used linear viscoelastic model is employed to determine the collision force of the friction pair, with the equation given as follows:

In the formula,

ks represents the impact stiffness coefficient,

cs represents the collision damping coefficient, and

δd represents the contact deformation quantity. The collision event within the friction pair occurs at the locus of maximal axial relative displacement between the outer circumferential steel plate and the friction plate. Consequently, the time-varying contact deformation quantity equates to the peak axial relative displacement minus the initial clearance of the friction pair at said critical position.

In the formula, Zmax represents the maximum circumferential axial displacement of the friction pair, and h0 represents the initial gap of the friction pair.

2.2.2. Rotational Moment Equation of Frictional Components

Conventional modeling of friction plate rotational moments presupposes dominant contributions from collision-induced moments about orthogonal

x or

y axes. However, any pendulum-type tilting motion of the friction plate induces asymmetric moment arms for centrifugal forces generated by differential mass elements. This kinematic asymmetry yields non-zero net moments about both axes, ultimately producing a dynamic unbalanced centrifugal moment field. Since the friction plate rotates at high speed, it exhibits gyroscopic behavior. The friction disc can be treated as a rigid-body gyroscopic system due to its high-speed rotational kinematics. In addition to self-rotation, the friction disc also undergoes swinging around the

x and

y axes. This motion state inevitably generates a gyroscopic moment, and this moment increases as the self-rotation angular speed increases. Therefore, the gyroscopic moment in high-speed rotating friction discs must not be ignored. Structured analysis demonstrates that the restoring torque on the friction disc about the

x–y axes comprises three distinct mechanical components, expressed as

In the formula,

Mzx and

Mzy represent the impact-induced restoring torque,

MCx and

MCy represent the mass-unbalance-derived restoring torque, and

MGx and

MGy represent the gyroscopic-effect-generated restoring torque [

25].

2.2.3. Contact-Induced Drag Torque of Friction Pair

By substituting the impact force equation (Equation (18)) and the restoring torque (Equation (20)) of the friction pair into the fluid–structure interaction dynamic model (Equation (17)), the impact force acting on the friction pair (

Fz) can be obtained through a numerical solution. The collision-induced tangential friction force, derived from the product of the impact force and friction coefficient, and this friction force multiplied by the outer radius

r0 of the friction pair yields the drag torque from collision friction:

In the formula, f represents the steel–disc interfacial friction coefficient.

2.3. Generalized Drag Torque Model Covering Wide-Speed Domains

The drag torque in unloaded wet clutches primarily consists of two components: viscous fluid friction-induced drag torque and collision-induced drag torque. The viscous component depends on relative speed and the clearance gap. Viscous shear friction arises whenever relative motion occurs; consequently, viscosity-based drag torque persists across all speed regimes—from near-static conditions to high rotational velocities.

Regarding collision-induced drag torque, negligible steel–disc collisions occur at low rotational velocities—consequently, such torque remains absent in low-speed regimes. As rotational speed escalates, intensifying unbalanced centrifugal forces and gyroscopic moments induce steel–disc interfacial collisions, generating progressively increasing collision torque.

Integrating these dynamic characteristics with viscous friction torque’s speed-invariant nature, we propose a unified drag torque model applicable across wide-speed ranges:

4. Wide Speed Domain Drag Torque Suppression Optimization Design

Current research, for the most part, focuses on analyzing clutch friction plate groove characteristics and drag torque suppression at low and high speeds, but lacks methods suitable for wide speed domains, making it difficult for traditional approaches to effectively suppress drag torque across wide speed ranges. The groove profile determines the distribution of the clearance flow field, which governs the viscous shear-induced drag torque. Therefore, this study utilizes the fluid–structure interaction (FSI) dynamic model established earlier. Focusing on general curved groove geometries, this study conducts geometric topology optimization of grooves on friction plates, resulting in reduced drag torque. It establishes a parametric design optimization model for friction pairs and develops a strategy for wide speed domain drag torque suppression.

4.1. General Curve Groove Parametric Modeling

To investigate the optimization of general curved groove geometries, this paper first defines the groove profile with finite discrete points when configuring the groove (see

Figure 8a). Subsequently, function interpolation is employed to reconstruct the entire profile curve, and the resulting interpolation function serves as the mathematical expression for the groove profile.

As shown in

Figure 8b, a function interpolation method is used from discrete points to obtain the groove profile schematic diagram.

Pk represents the prescribed discrete control nodes,

K represents the nodal indexing scheme, and

Npionts represents the controlled node population.

In engineering practice, spline curves are widely employed for geometrical representation. Consequently, this study adopts cubic spline interpolation for parametric groove profile construction [

26].

In the formula, Mk represents the second derivative value at point Pk.

Under natural boundary conditions with

M0 =

Mn = 0 at endpoints, the second-derivative matrix of the interpolant is computed via the three-moment equation.

During computation, the discrete coordinate values are utilized to evaluate Equations (25) and (26). These results are then substituted into Equation (24) to compute the second-derivative matrix M of the interpolant. Subsequent integration into Equation (23) yields all coefficients of the cubic spline interpolation polynomial, thereby establishing the parametric expression for general curve groove profiles.

During the parametric optimization, four equally spaced reference points are radially selected from the initial profile

(

Figure 9). By modifying angular coordinates while maintaining radial invariability, four new discrete nodes are generated to construct the optimized profile

thereby defining a novel groove configuration. The coordinate transformation between the optimized and initial profiles is expressed as

These procedures reduce the optimization of general curve groove profiles to a parametric refinement of the initial groove geometry coupled with numerical optimization of the circumferential angular offset matrix [a, b, c].

4.2. Optimal Design of the Model

- (1)

Design variables

The oil groove structural parameters and groove profile parameters of the wet clutch friction pair are selected as design variables, totaling eight parameters for optimization.

In the formula, Ng represnts number of oil grooves, hg represents groove depth, δr = (rg − ri)/(ro − ri) represents the radial dam ratio, and φi (i = 1~4) represents the offset angle of discrete points in the circumferential direction.

- (2)

Constraint conditions

During multi-parameter optimization of friction pairs, it is imperative not only to reduce computational complexity but also to holistically evaluate the machinability of friction plate oil grooves, clutch operational performance, and engineering expertise.

Consequently, constraints must be applied to the correlations and bounded value ranges of optimization variables. Furthermore, torque transmission capacity and lubrication-cooling requirements must be addressed. Since an inadequate or excessive groove area ratio detrimentally impacts performance, the effective contact area coefficient (

ψ) requires constrained optimization.

The constraint function is defined as follows:

- (3)

Optimization objectives

This study takes the peak drag torque (

Ts) at low speeds and the total drag torque (

T) at the highest rotational speed as key evaluation indicators. The target function established below targets minimization of these two values simultaneously.

In the formula, X denotes the eight parameters for optimization, with ‘min’ specifying the minimization objective. This target function adjusts groove parameters to minimize wide speed domain drag torque, thereby achieving concurrent reduction of the low-speed peak drag torque (Ts) and the high-speed total drag torque (T) at maximum rotational speed.

4.3. Solution Method

This study optimizes eight design parameters for wet clutch friction pairs. First, the optimization variables defined in Equation (28) are partitioned into two groups for sequential optimization. An optimal Latin hypercube design generates 150 sample points, which are computationally evaluated through the multi-plate fluid–structure interaction (FSI) rub-impact dynamic model and the wide-speed-domain drag torque model. Sensitivity analysis quantifies parametric effects on the objective function. Subsequently, an elliptic basis neural network (EBNN) surrogate model is constructed to approximate the nonlinear relationship between the FSI rub-impact model and drag torque model, significantly enhancing computational efficiency. The multi-island genetic algorithm (MIGA) is then employed for global optimization, leveraging its proven convergence robustness to obtain the optimized parameter set. This integrated approach, combining design of experiments, surrogate modeling, and evolutionary algorithms, establishes an efficient methodology for multi-parameter optimization of friction pairs in complex flow environments.

4.4. Optimization Results

The NSGA-II multi-objective optimization algorithm was employed to solve the design optimization model. The geometric dimensions of friction pairs, condition parameters, and design parameter constraints involved in the optimization process are comprehensively specified in

Table 3.

The optimal solution for the eight parameters obtained through optimization is presented in

Table 4. To validate the data efficacy, five sets of feasible design variables were randomly selected for comparative analysis with the optimal solution. Results demonstrate that the optimal solution achieves the most significant drag torque reduction. The corresponding geometric configuration of the friction plate surface is illustrated in

Figure 10.

5. Wide Speed Domain Drag Torque Suppression Optimization Test Verification

To validate the feasibility of reducing drag torque through optimized groove configurations on friction plates, multiple groups of friction plates with distinct groove geometries were selected for experimental comparison. The test parameters were as follows: friction pair average clearance

h0 = 0.5 mm, inlet flow rate

Q = 1.5 L/min, and oil temperature T = 40 °C.

Figure 11a shows the radial groove friction plate specimen, while

Figure 11b presents the 70° spiral groove variant. Both specimens feature 18 grooves with a uniform depth of 0.5 mm.

As shown in

Figure 12, the radial groove friction plate exhibits a peak drag torque of 16 N·m in the low-speed regime, while the values for the 70° spiral groove and optimized groove plates are 12 N·m and 8 N·m, respectively. Relative to the radial and spiral groove designs, the optimized plate achieves drag torque reductions of 50.0% and 33.3%.

The critical rubbing speed in the high-speed regime demonstrates substantial enhancement. Specifically, the radial groove, 70° spiral groove, and optimized groove friction plates initiate rubbing at 3200 rpm, 3000 rpm, and 3500 rpm, respectively. Compared to the radial and spiral groove designs, the optimized groove configuration exhibits 9.4% and 16.7% increases in critical rubbing speed. This phenomenon occurs because the optimized groove configuration enhances the dynamic pressure effects within the flow field, thereby increasing hydrodynamic stiffness and improving operational stability. Furthermore, the drag torque during rubbing (viscous shear friction coupling effects) of the optimized groove plate remains markedly lower compared to conventional designs (radial/spiral grooves), without exhibiting significant amplification at high rotational speeds.

In conclusion, our experimental findings demonstrate that the optimized groove friction plate achieves the following:

- (1)

Reduces peak drag torque by 18–25% in low-speed operations.

- (2)

Elevates the threshold speed for viscous shear friction coupling effects.

- (3)

Maintains consistently low drag torque across high-speed ranges, thereby minimizing no-load power losses by approximately 11–15%.