4.2. Steady-State Characteristics

Based on the parameters given in

Table 3, the base speed, the boundary speed, and the critical speed can be calculated as described in

Section 3. The calculated values for the nominal machine parameters are as follows:

[rad/s],

[rad/s], and

[rad/s]. To present the effect of

on these speed values, the calculated base, boundary, and critical speeds are given in

Table 4 for five different iron loss resistance values. It can be concluded that the base speed slightly increases while the boundary speed slightly decreases if the value of

starts to decrease, that is, if iron loss starts to become significant. The effect of

is more obvious on the value of critical speed: this speed value can increase by several percent if the resistance representing the iron loss is taken into account.

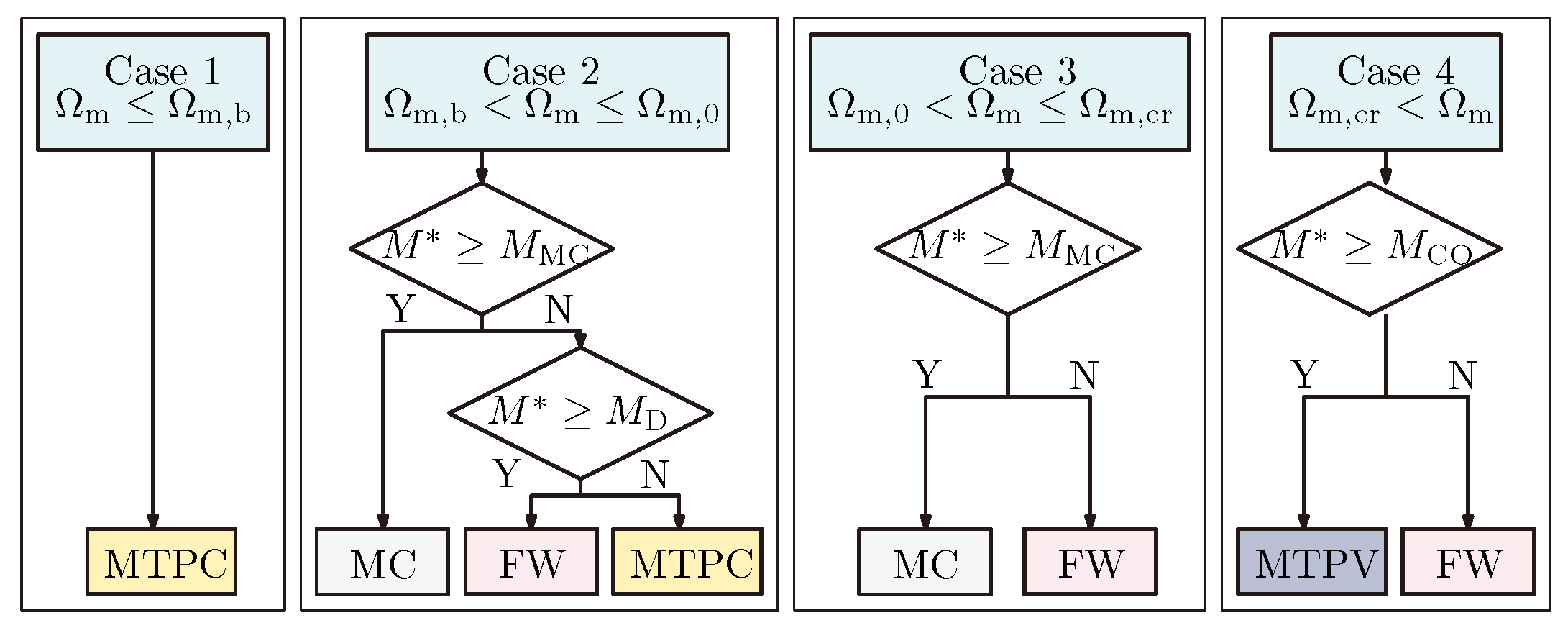

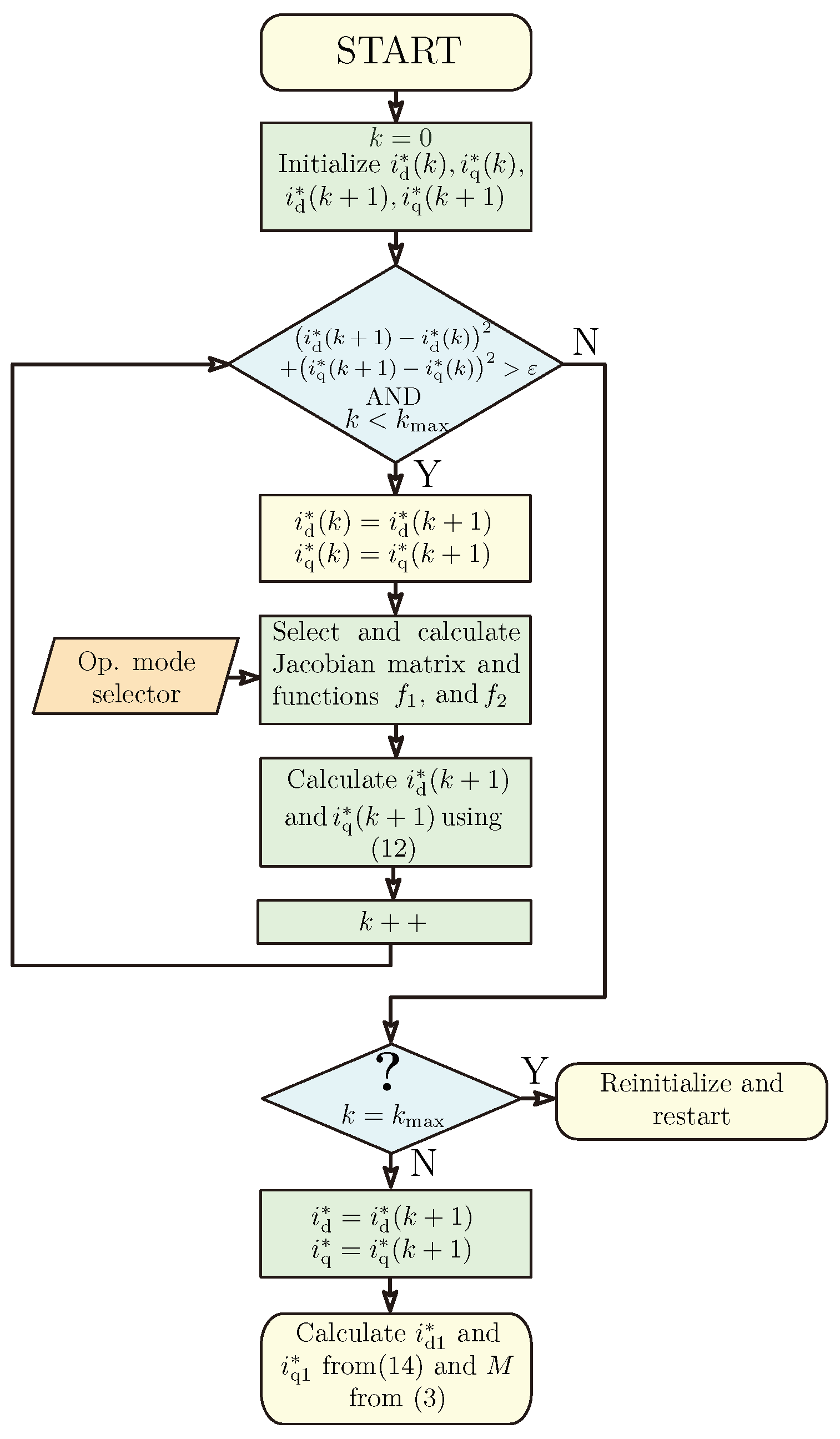

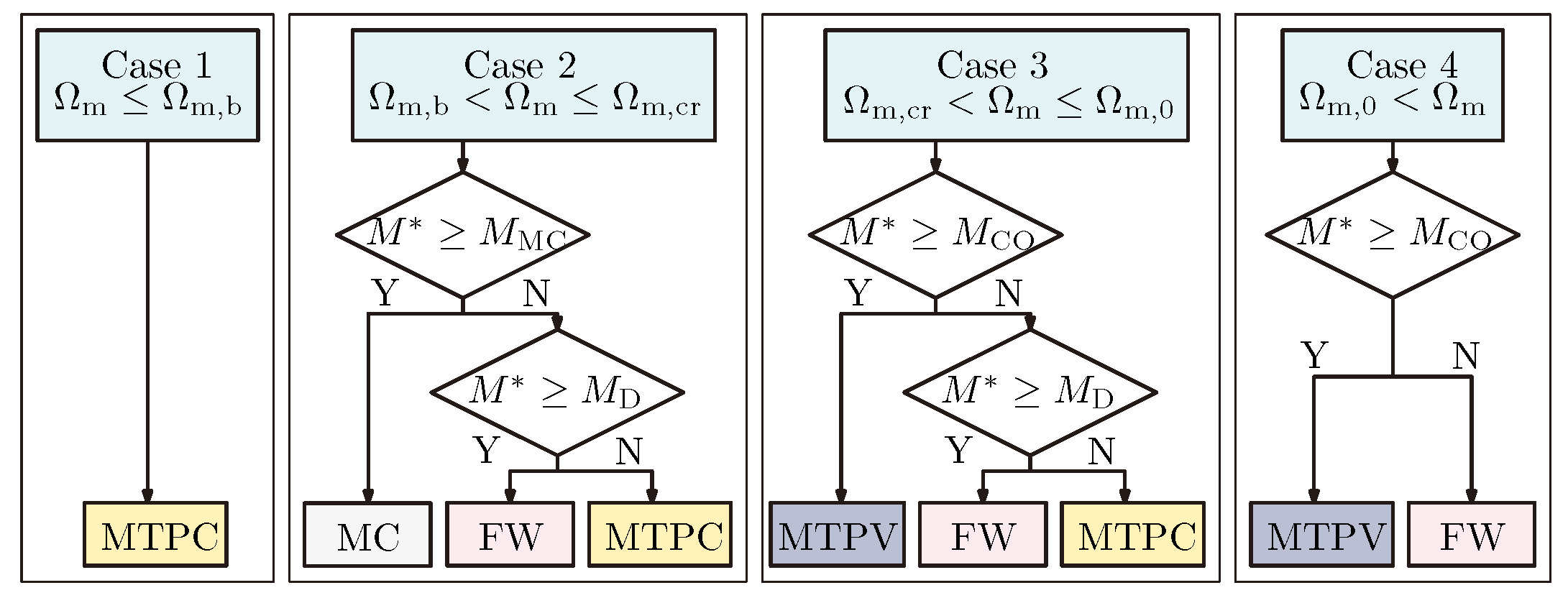

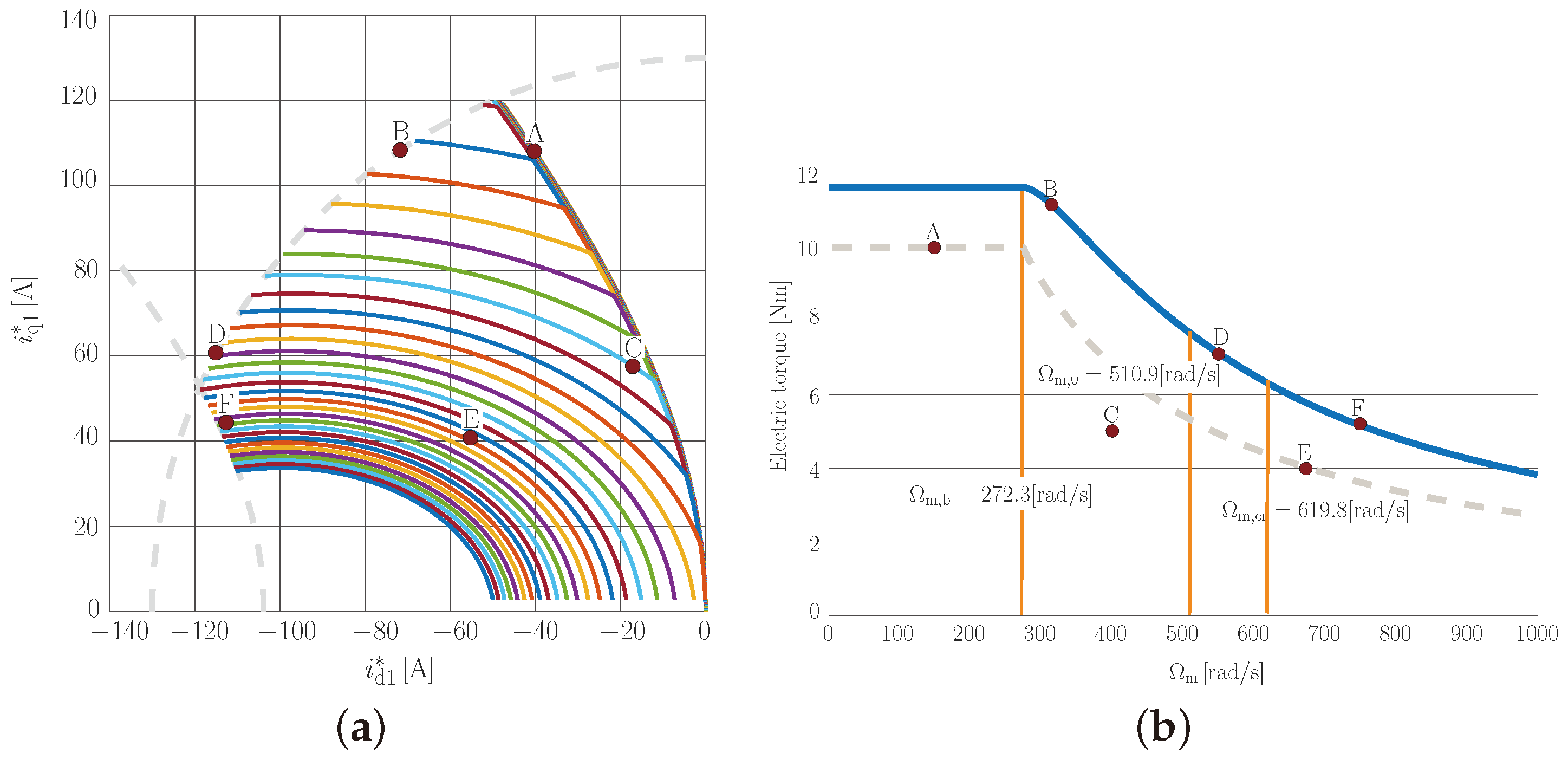

Figure 8a shows the numerically calculated trajectories of

reference current pairs by sweeping the

reference torque from zero up to its maximum value (see

in

Table 3) at different constant

mechanical speed values. The

values were varied between 0 and 1000 rad/s, in steps of 25 rad/s. For better visibility, the current limit circle and the MTPV curve belonging to the critical speed have been marked with a dashed line. The algorithm can be seen to provide the reference currents in the MTPC, MC, FW, and MTPV regions.

Figure 8b shows the achievable electric torque of the machine as a function of mechanical speed. The base speed, boundary speed, and critical speed are also marked in the figure. As can be seen in the figure, below the base speed, the machine can produce its maximum torque

. Above the base speed, the achievable electric torque decreases with increasing mechanical speed. The dashed line in

Figure 8b presents the allowable torque of the machine for continuous operation as a function of the mechanical speed. Below the base speed, the machine can generate nominal torque (constant torque region) while it provides nominal power above the base speed (constant power region) for continuous duty.

As previously mentioned, in the literature, the effect of iron loss resistance is typically neglected during reference current calculation. To demonstrate the effect of iron loss resistance and why it is important to consider in the calculations,

Table 5 shows how

and

current components as well as the electric torque differ if iron loss is not taken into account during the reference calculations, even though the machine has a certain amount of

resistance. The calculations were carried out for six different working points (denoted by A, B…F) and for five different

values. For better comparability, these working points are examined in subsequent studies as well. The second column of

Table 5 (titled

) shows the calculated

and

reference current components by neglecting the effect of iron loss. The achievable electric torque is also calculated from (

3) by assuming that the current controllers work properly, and in the steady state,

and

track their reference signals. If the machine has a non-negligible iron loss (expressed with

resistance as given in

Figure 1), then

and

. As can be seen in

Table 5, in the case of columns for different

values, as the effect of iron loss becomes more and more significant (

decreases), the difference between the controlled

and

stator current components and the actual

and

current components, which are important in terms of torque generation, becomes considerable. These differences mean that the value of the achievable electric torque is reduced and the current controller cannot provide the reference torque. From the table, it can be concluded that, in certain operation ranges (MTPC, MC, MTPV), these differences are in the range of a few percent, even in the case of a low

. However, in the FW operation region, a much more dominant difference can be seen. For example, the relative reduction in electric torque at working point A is 1% (

) and 2% (

), respectively. At the same time, at working points C and E, this value is 4% (

)/7.9% (

)/5% (

)/10% (

), respectively.

Based on

Table 5, it is clear that, if the machine has a non-negligible iron loss, its effect should be considered in the reference current calculation using the proposed method introduced in the current manuscript.

Table 6 shows the calculated

d and

q axis reference currents and the achievable electric torque for the same working points (denoted by A, B…F) and

values using the proposed reference current calculation algorithm. These working points are also denoted in

Figure 8a,b. It should be noted that the calculated values given in the second column titled

are the same as the second column given in

Table 5. Based on the values given in

Table 6, it can be concluded that, for working points found in the MC or MTPV regions (such as working points B, D, and F), taking the effect of

into account only slightly modifies the calculated

d and

q axis reference currents, compared to the case when the effect of iron loss is neglected. However, for working points located in either the MTPC or FW regions (such as working points A, C, and E), considering the effect of

modifies the reference currents much more significantly. As can be seen, in these points, the machine can provide the reference torque, even when the effect of iron loss is considerable. It is a clear advantage of the proposed reference current calculation method as, in these working points, the machine cannot guarantee the reference torque if

is not considered (compare values belonging to working points A, C, and E in

Table 5 and

Table 6).

4.3. Closed-Loop Operation

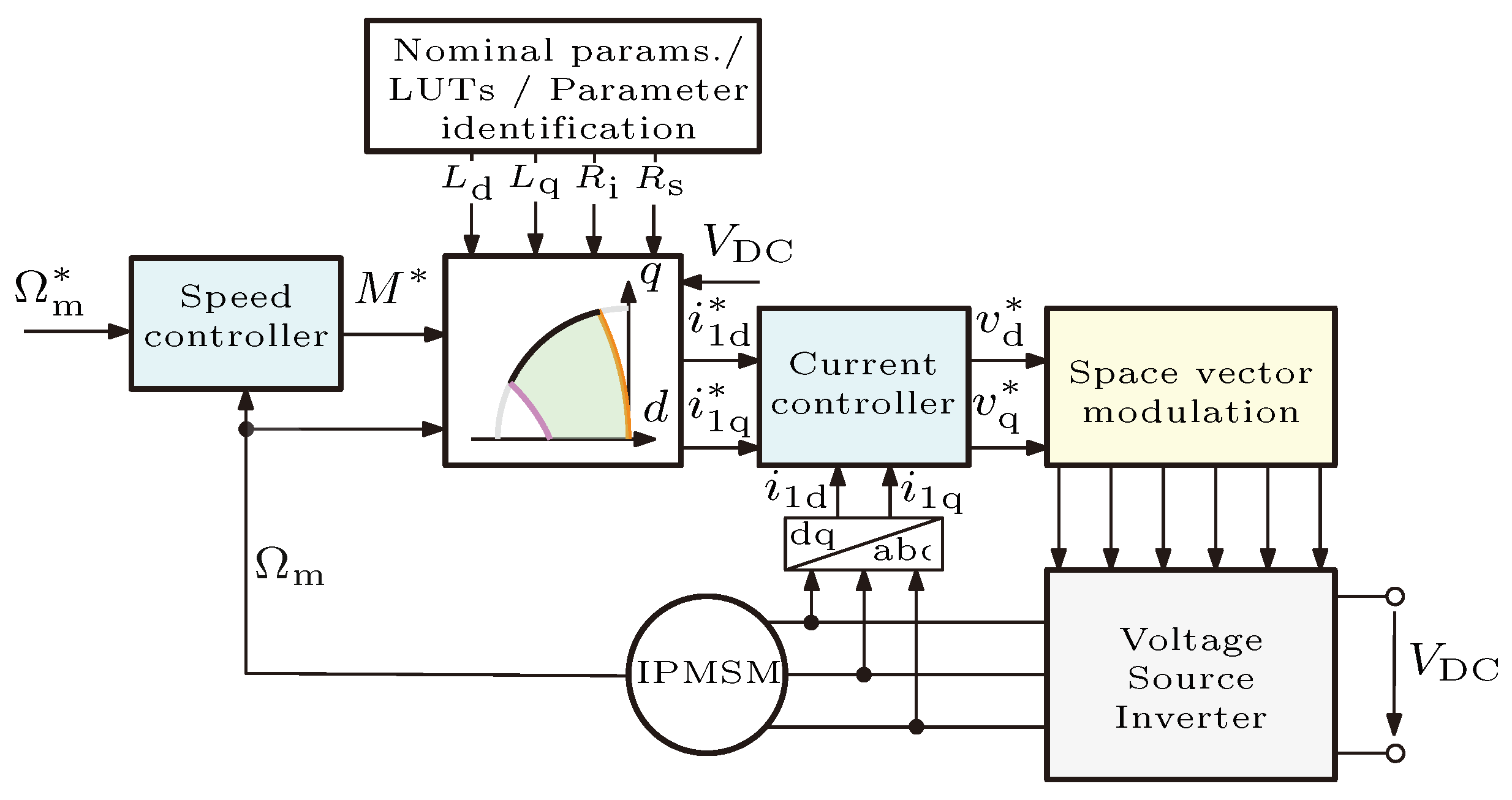

In order to verify the proposed reference current calculation strategy in different operation modes, a closed control loop was constructed in the MATLAB/Simulink R2023a environment similar to the block diagram in

Figure 3. During the simulation study, the nominal machine parameters given in

Table 3 were used. The current reference calculation algorithm was run at a sampling rate of 2 kHz, while the sampling time of the inner current loop was selected to be 20 kHz. The switching frequency of the VSI was 10 kHz. The sampling of the phase currents was synchronized to the positive and negative peaks of the carrier signal used for space vector modulation. The gains of the current controllers were calculated using the modulus optimum method, considering a one-step delay as well as

and

for the

d axis current controller and

and

for the

q axis current controller.

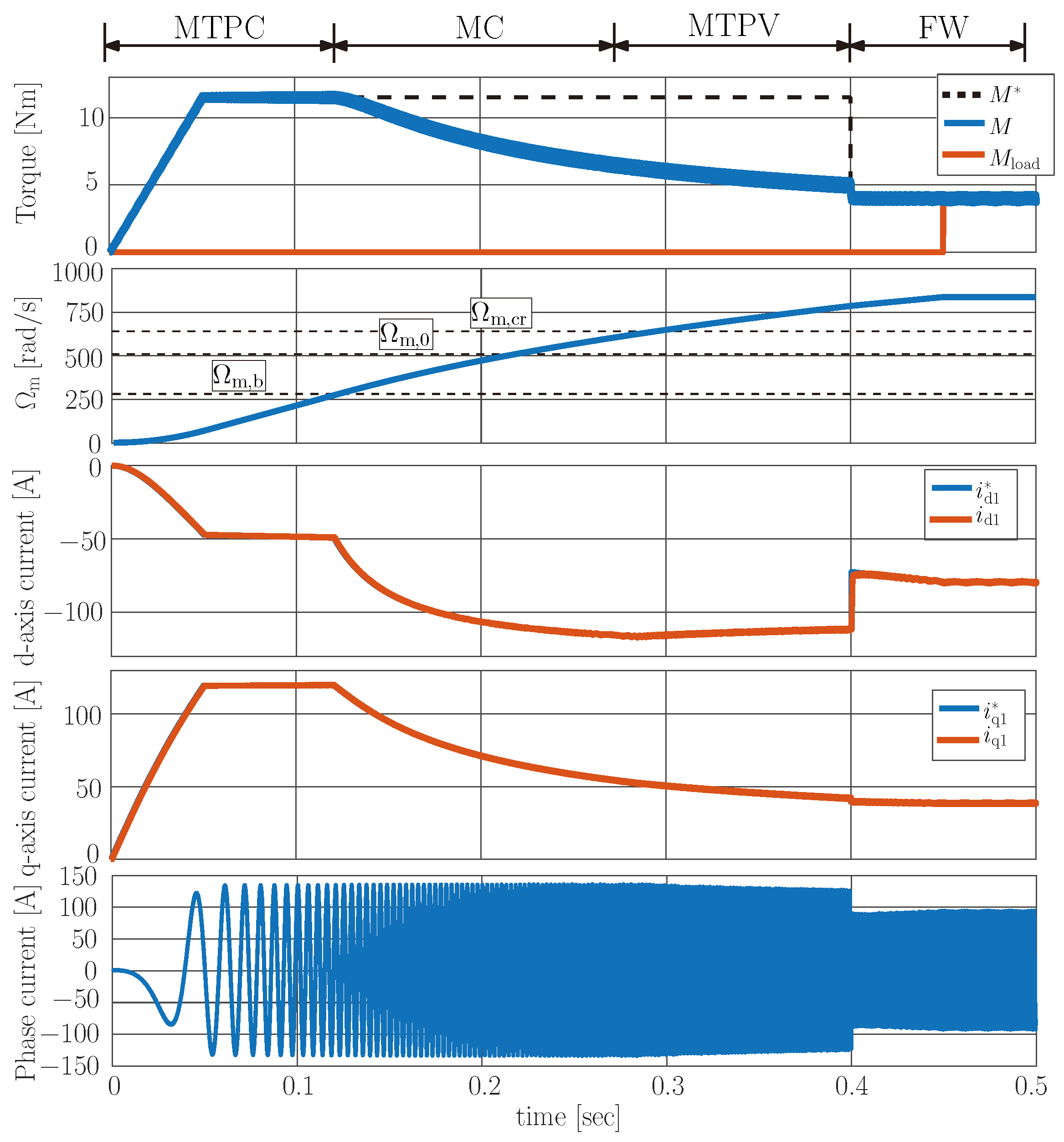

As a first step, the outer speed controller was not considered, and the actual value of the

reference torque was generated externally.

Figure 9 shows the simulated waveforms of the torque, mechanical speed,

d and

q axis current components, and one phase current. The

values were changed from 0 up to

with a ramp signal, and the loading torque was zero. The mechanical speed was increasing, and the machine worked along the MTPC curve. At

, the mechanical speed exceeded the base speed, and the machine entered the MC region, where both the current and the voltage reached their limit values. As can be seen, the IPMSM could not provide the reference torque anymore, so the machine accelerated further with a smaller rate. After that, the mechanical speed exceeded the

boundary speed, and then, at

s, it exceeded the

critical speed as well. From this point on, the machine operated along the MTPV trajectory. At

s, the reference torque was reduced to 4 Nm. The machine started to operate in the FW region. At

s, a loading torque of 4 Nm was applied, and the mechanical speed settled down.

Figure 10 shows the trajectory of

d and

q axis current in the

–

plane. The trajectories of the MTPC, MC, MTPV, and FW regions are clearly visible.

Based on the simulated results, it can be concluded that the control requirements are fulfilled, and the current signals follow the reference signals. The IPMSM can work in the MTPC, MC, MTPV, and FW regions, and the voltage and current limits were not violated.

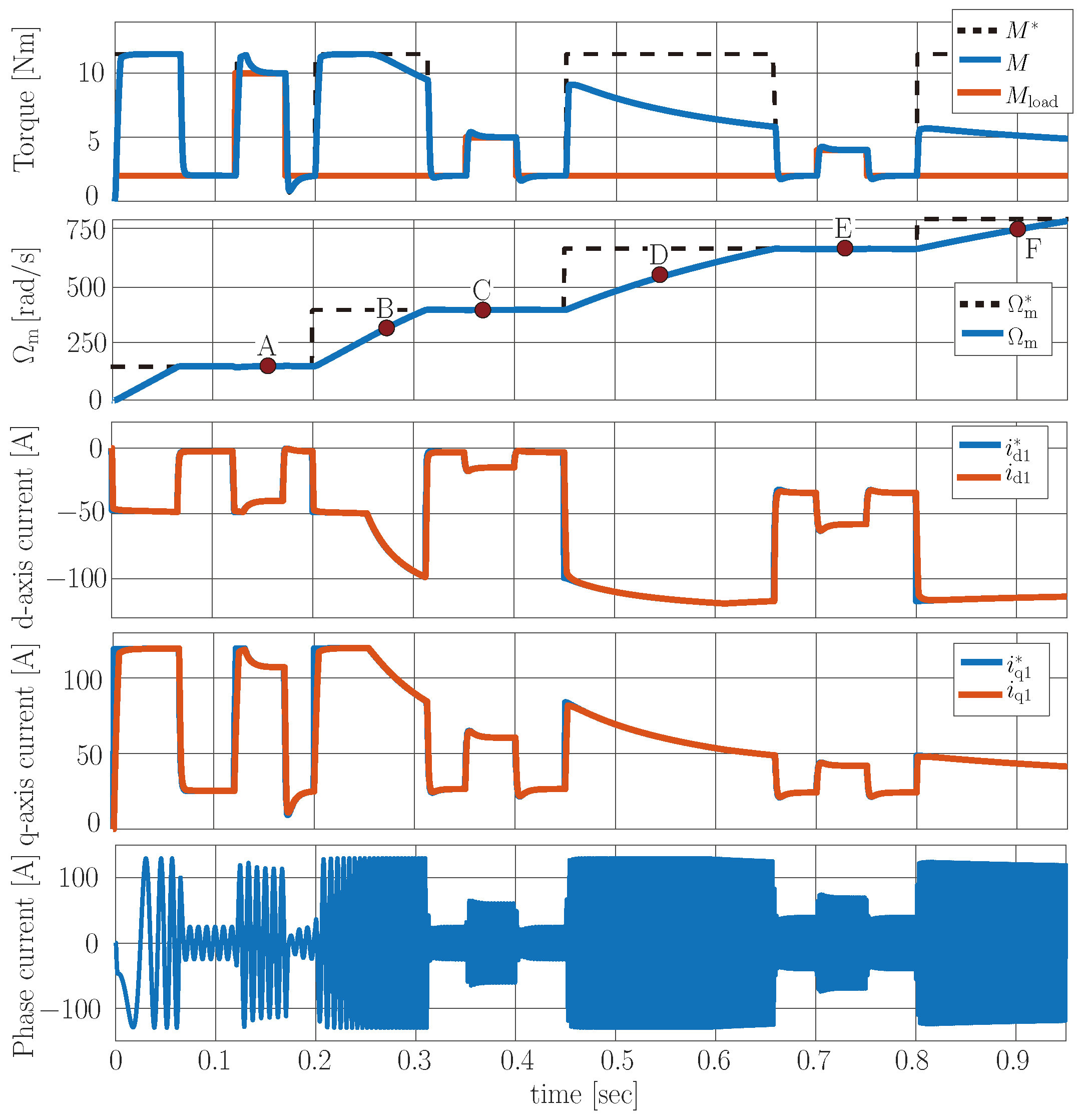

As a second step, the external speed controller was also considered in the simulation. The PI-type speed controller forms the

reference torque based on the difference between the

reference and the actual mechanical speed

. The discrete PI speed controller ran at a sampling rate of 2 kHz, similarly to the current reference generation algorithm. The gains of the controller were calculated using the symmetrical optimum method as

and

.

Figure 11 shows the simulated waveforms of the torque, mechanical speed,

d and

q axis current components, and one phase current. The trends for the reference mechanical speed and the load torque were determined so that, during the simulation, the drive worked at the working points (see points A, B…F in

Figure 8) given in

Section 4.2. As can be seen, the current reference generation algorithm works properly for sudden changes in both the reference speed and loading torque. The simulated values are consistent with the calculated quantities (see

Table 6,

).