Three-Locus Sequence Identification and Differential Tebuconazole Sensitivity Suggest Novel Fusarium equiseti Haplotype from Trinidad

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

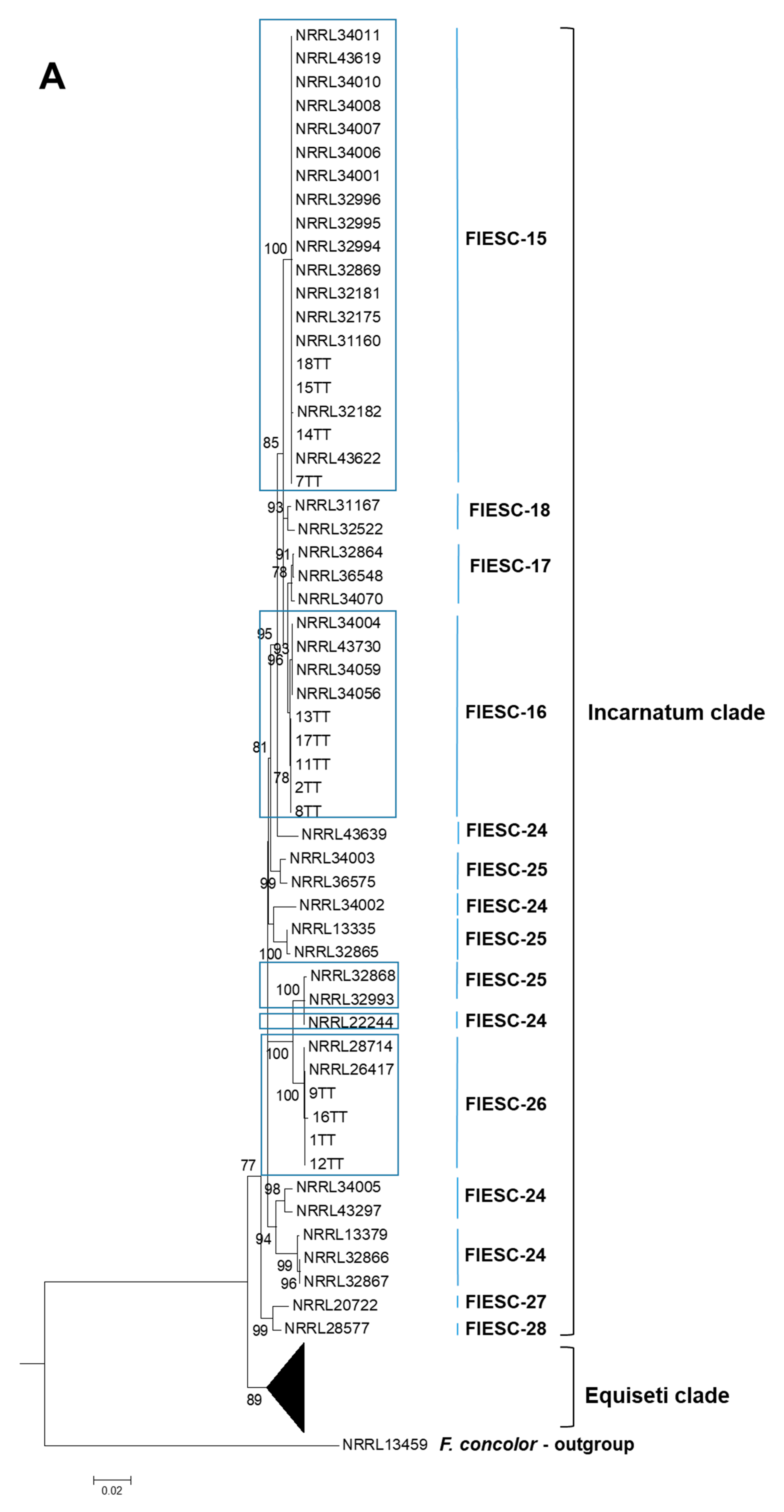

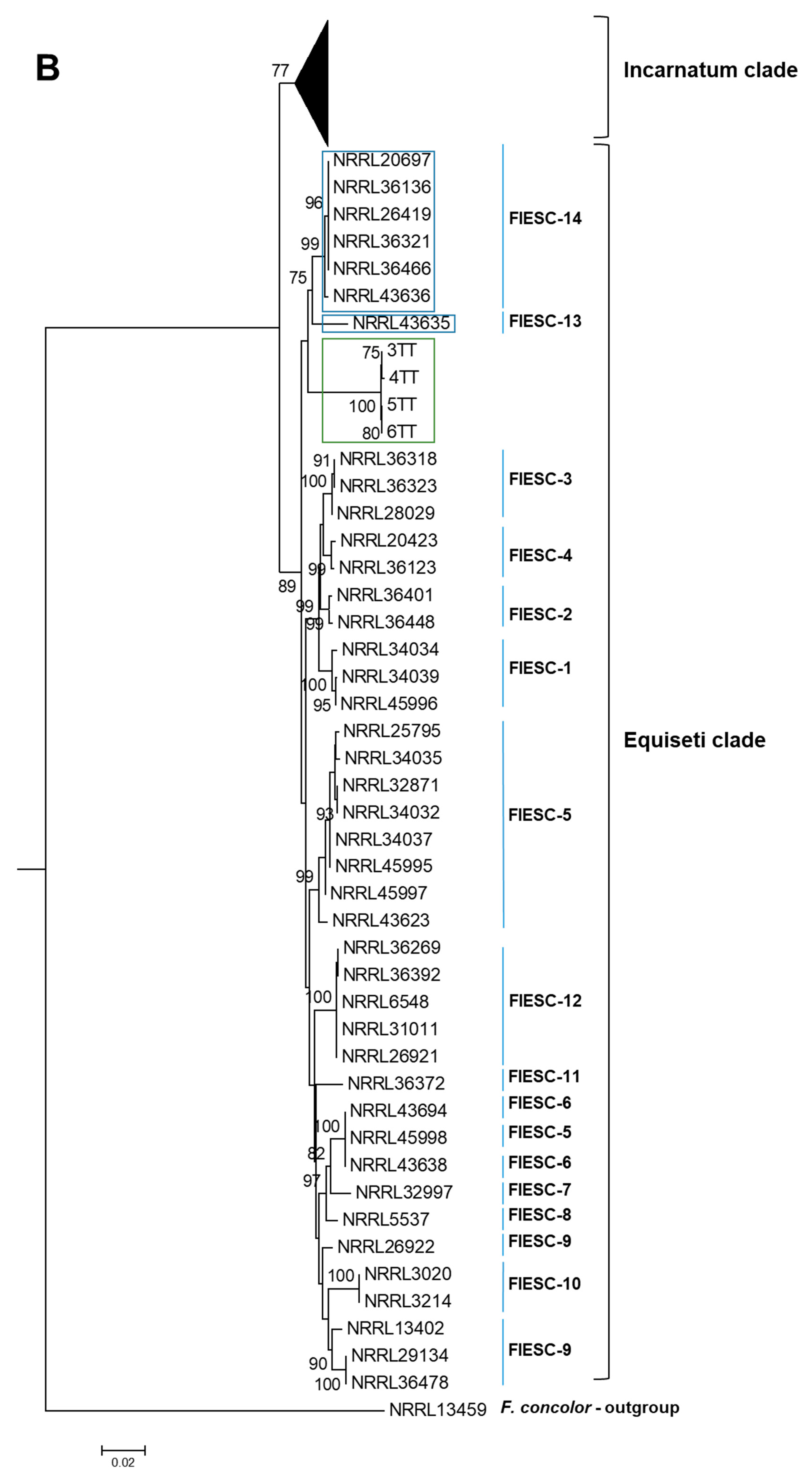

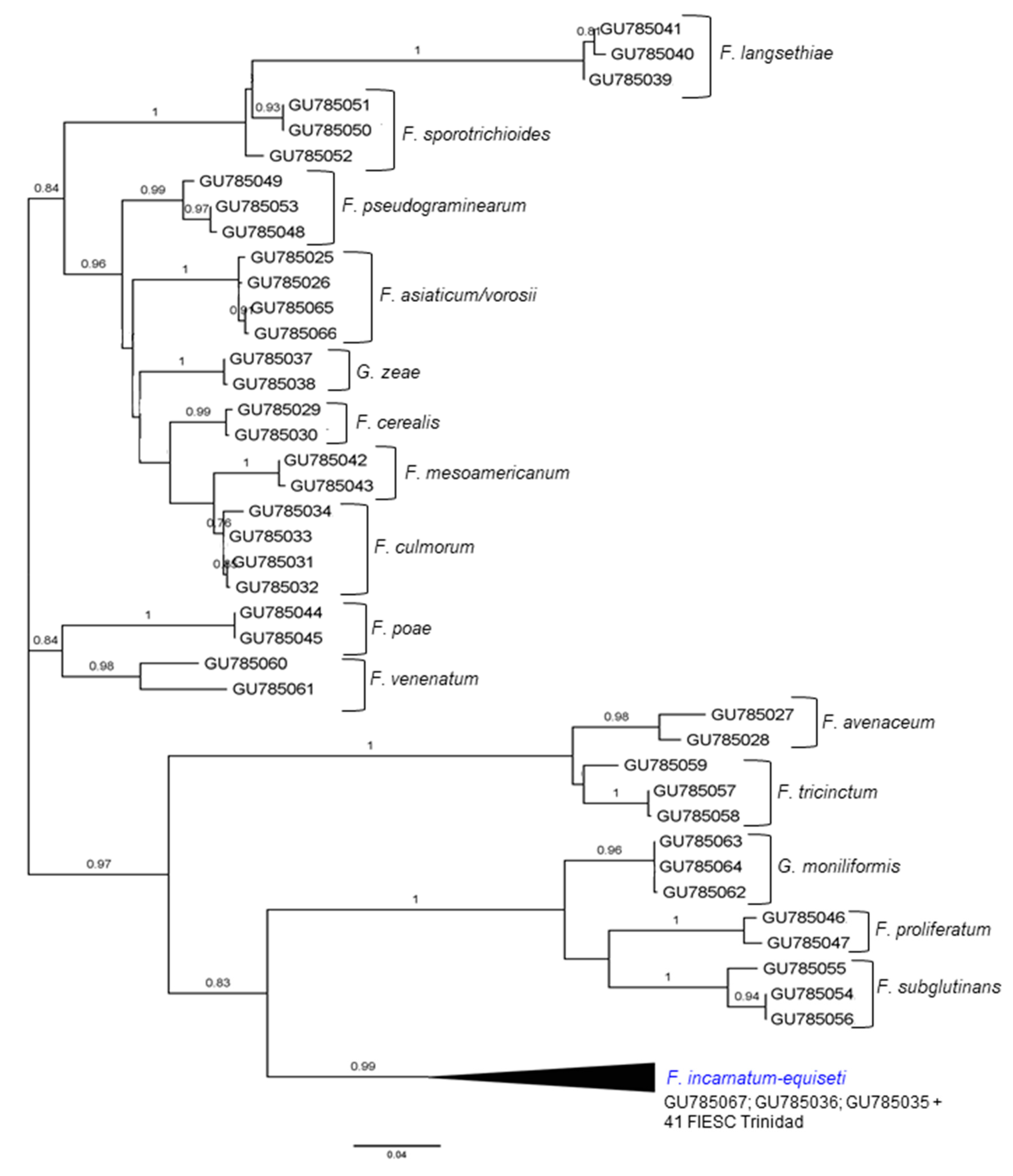

2.1. The Identification and Phylogenetic Placement of Isolates

2.2. Tebuconazole Phenotypes

2.3. CYP51C Sequence Analysis

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Collection of Isolates

4.2. DNA Extraction, PCR Amplification, and Sequencing

4.3. Multi-locus Sequencing Typing (MLST) for Phylogenetic Species Identification

4.4. Phylogenetic Analysis

4.5. Fungicide Sensitivity

4.6. Genetic Structure of CYP51C

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Statistics. 2017 FAOSTAT Database. Available online: http://faostat3.fao.org/ (accessed on 3 January 2020).

- Utkhede, R.S.; Mathur, S. Internal fruit rot caused by Fusarium subglutinans in greenhouse sweet peppers. Can. J. Plant. Pathol. 2004, 26, 386–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Poucke, K.; Monbaliu, S.; Munaut, F.; Heungens, K.; De Saeger, S.; Van Hove, F. Genetic diversity and mycotoxin production of Fusarium lactis species complex isolates from sweet pepper. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2012, 153, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Chen, L.; Yong, X.; Shen, Q. Formulations can affect rhizosphere colonization and biocontrol efficiency of Trichoderma harzianum SQR-T037 against Fusarium wilt of cucumbers. Biol. Fert. Soils. 2011, 47, 239–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, T.; Mayne, S. Pepper Fruit Rots; HDC: Kenilworth, Warwickshire, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Damm, U.; Woudenberg, J.H.; Cannon, P.F.; Crous, P.W. Colletotrichum species with curved conidia from herbaceous hosts. Fung. Divers 2009, 39, 45. [Google Scholar]

- Ramdial, H.A.; Rampersad, S.N. First report of Fusarium solani causing fruit rot of sweet pepper in Trinidad. Plant Dis. 2010, 94, 1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramdial, H.; Hosein, F.; Rampersad, S.N. First report of Fusarium incarnatum associated with fruit disease of bell peppers in Trinidad. Plant Dis. 2016, 100, 526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellá, G.; Cabañes, F.J. Phylogenetic diversity of Fusarium incarnatum-equiseti species complex isolated from Spanish wheat. Antonie Van. Leeuwenhoek 2014, 106, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marín, P.; Jurado, M.; Gonzalez-Jaen, M.T. Growth rate and TRI5 gene expression profiles of Fusarium equiseti strains isolated from Spanish cereals cultivated on wheat and barley media at different environmental conditions. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2015, 195, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Villani, A.; Moretti, A.; De Saeger, S.; Han, Z.; Di Mavungu, J.D.; Soares, C.M.; Proctor, R.H.; Venâncio, A.; Lima, N.; Stea, G.; et al. A polyphasic approach for characterization of a collection of cereal isolates of the Fusarium incarnatum-equiseti species complex. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2016, 234, 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desjardins, A.E. Fusarium Mycotoxins: Chemistry, Genetics, and Biology; American Phytopathological Society Press: St. Paul, MN, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Desjardins, A.E.; Proctor, R.H. Molecular biology of Fusarium mycotoxins. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2007, 119, 47–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donnell, K.; Sutton, D.A.; Rinaldi, M.G.; Gueidan, C.; Crous, P.W.; Geiser, D.M. Novel multilocus sequence typing scheme reveals high genetic diversity of human pathogenic members of the Fusarium incarnatum-equiseti and F. chlamydosporum species complexes within the United States. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2009, 47, 3851–3861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Diepeningen, A.D.; Brankovics, B.; Iltes, J.; van der Lee, T.A.; Waalwijk, C. Diagnosis of Fusarium infections: Approaches to identification by the clinical mycology laboratory. Curr. Fungal Infect. Rep. 2015, 9, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Diepeningen, A.D.; de Hoog, G.S. Challenges in Fusarium, a trans-kingdom pathogen. Mycopathologia 2016, 181, 161–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moretti, M.L.; Busso-Lopes, A.F.; Tararam, C.A.; Moraes, R.; Muraosa, Y.; Mikami, Y.; Gonoi, T.; Taguchi, H.; Lyra, L.; Reichert-Lima, F.; et al. Airborne transmission of invasive fusariosis in patients with hematologic malignancies. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0196426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiser, D.M.; del Mar Jiménez-Gasco, M.; Kang, S.; Makalowska, I.; Veeraraghavan, N.; Ward, T.J.; Zhang, N.; Kuldau, G.A.; O’Donnell, K. FUSARIUM-ID v. 1.0: A DNA sequence database for identifying Fusarium. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2004, 110, 473–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donnell, K.; Ward, T.J.; Robert, V.A.; Crous, P.W.; Geiser, D.M.; Kang, S. DNA sequence-based identification of Fusarium: Current status and future directions. Phytoparasitica 2015, 43, 583–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; O’Donnell, K.; Aoki, T.; Smith, J.A.; Kasson, M.T.; Cao, Z.M. Two novel Fusarium species that cause canker disease of prickly ash Zanthoxylum bungeanum in northern China form a novel clade with Fusarium torreyae. Mycologia 2016, 108, 668–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramdial, H.; De Abreu, K.; Rampersad, S.N. Fungicide sensitivity among isolates of Colletotrichum truncatum and Fusarium incarnatum-equiseti species complex infecting bell pepper in Trinidad. Plant. Pathol. J. 2017, 33, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Fungicide Resistance Action Committee. FRAC Code List 2019: Fungal Control Agents Sorted by Cross Resistance Pattern and Mode of Action (Including FRAC Code Numbering). Available online: https://www.frac.info/docs/default-source/publications/frac-code-list/frac-code-list-2019.pdf. (accessed on 30 August 2019).

- Ocamb, C.M.; Hamm, P.B.; Johnson, D.A. Benzimidazole resistance of Fusarium species recovered from potatoes with dry rot from storages located in the Columbia basin of Oregon and Washington. Am. J. Potato Res. 2007, 842, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, W.H.; Chung, W.C.; Ting, P.; Ru, C.C.; Huang, H.C.; Huang, J.W. Nature of resistance to methyl benzimidazole carbamate fungicides in Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. lilii and F. oxysporum f. sp. gladioli in Taiwan. J. Phytopathol. 2009, 157, 742–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Gao, T.; Liang, S.; Liu, K.; Zhou, M.; Chen, C. Molecular mechanism of resistance of Fusarium fujikuroi to benzimidazole fungicides. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2014, 357, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevastos, A.; Labrou, N.E.; Flouri, F.; Malandrakis, A. Glutathione transferase-mediated benzimidazole-resistance in Fusarium graminearum. Pest. Biochem. Physiol. 2017, 141, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cools, H.J.; Hawkins, N.J.; Fraaije, B.A. Constraints on the evolution of azole resistance in plant pathogenic fungi. Plant. Pathol. 2013, 62, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brent, K.J.; Hollomon, D.W. Fungicide Resistance in Crop. Pathogens: How Can. It be Managed? GIFAP: Brussels, Belgium, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Shyadehi, A.Z.; Lamb, D.C.; Kelly, S.L.; Kelly, D.E.; Schunck, W.-H.; Wright, N.J.; Corina, D.; Akhtar, M. The mechanism of the acyl-carbon bond cleavage reaction catalyzed by recombinant sterol 14α-demethylase of Candida albicans other names are: Lanosterol 14α-demethylase, P-45014DM, and CYP51. J. Biol. Chem. 1996, 271, 12445–12450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skaggs, B.A.; Alexander, J.F.; Pierson, C.A.; Schweitzer, K.S.; Chun, K.T.; Koegel, C.; Barbuch, R.; Bard, M. Cloning and characterization of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae C-22 sterol desaturase gene, encoding a second cytochrome P-450 involved in ergosterol biosynthesis. Gene 1996, 169, 105–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellado, E.; Diaz-Guerra, T.M.; Cuenca-Estrella, M.; Rodriguez-Tudela, J.L. Identification of two different 14-α sterol demethylase-related genes cyp51A and cyp51B in Aspergillus fumigatus and other Aspergillus species. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2001, 397, 2431–2438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weete, J.D.; Abril, M.; Blackwell, M. Phylogenetic distribution of fungal sterols. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e10899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becher, R.; Wirsel, S.G. Fungal cytochrome P450 sterol 14α-demethylase CYP51 and azole resistance in plant and human pathogens. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2012, 95, 825–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, J.E.; Warrilow, A.G.; Price, C.l.; Mullins, J.G.; Kelly, D.E.; Kelly, S.L. Resistance to antifungals that target CYP51. J. Chem. Biol. 2014, 7, 143–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diao, X.; Han, Y.; Liu, C. The fungicidal activity of tebuconazole enantiomers against Fusarium graminearum and its selective effect on DON production under different conditions. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018, 66, 3637–3643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, R.; Deng, L.; Li, J.; Gao, Y.; Liu, C. Effect of Tebuconazole Enantiomers and Environmental Factors on Fumonisin Accumulation and FUM Gene Expression in Fusarium verticillioides. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018, 66, 13107–13115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Price, C.L.; Parker, J.E.; Warrilow, A.G.; Kelly, D.E.; Kelly, S.L. Azole fungicides–understanding resistance mechanisms in agricultural fungal pathogens. Pest. Manag. Sci. 2015, 71, 1054–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson-Ziems, T.A.; Giesler, L.J.; Adesemoye, A.O.; Harveson, R.M.; Wegulo, S.N. Understanding Fungicide Resistance. Papers Plant Pathol. 2017, 481. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/320841209_Understanding_Fungicide_Resistance (accessed on 29 February 2020).

- Lepesheva, G.I.; Waterman, M.R. Sterol 14α-demethylase cytochrome P450 CYP51, a P450 in all biological kingdoms. BBA Gen. Subj. 2007, 177, 467–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becher, R.; Hettwer, U.; Karlovsky, P.; Deising, H.B.; Wirsel, S.G. Adaptation of Fusarium graminearum to tebuconazole yielded descendants diverging for levels of fitness, fungicide resistance, virulence, and mycotoxin production. Phytopathology 2010, 100, 444–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Urban, M.; Parker, J.E.; Brewer, H.C.; Kelly, S.L.; Hammond-Kosack, K.E.; Fraaije, B.A.; Liu, X.; Cools, H.J. Characterization of the sterol 14α-demethylases of Fusarium graminearum identifies a novel genus-specific CYP51 function. New Phytol. 2013, 198, 821–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Yu, F.; Schnabel, G.; Wu, J.; Wang, Z.; Ma, Z. Paralogous CYP51 genes in Fusarium graminearum mediate differential sensitivity to sterol demethylation inhibitors. Fung. Genet. Biol. 2011, 482, 113–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donnell, K.; Sutton, D.A.; Fothergill, A.; McCarthy, D.; Rinaldi, M.G.; Brandt, M.E.; Zhang, N.; Geiser, D.M. Molecular phylogenetic diversity, multilocus haplotype nomenclature, and in vitro antifungal resistance within the Fusarium solani species complex. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2008, 46, 2477–2490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vega-Bartol, J.J.; Martín-Dominguez, R.; Ramos, B.; García-Sánchez, M.-A.; Díaz-Mínguez, J.M. New virulence groups in Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. phaseoli: The expression of the gene coding for the transcription factor ftf1 correlates with virulence. Phytopathology 2011, 101, 470–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.J.; Geiser, D.M.; Proctor, R.H.; Rooney, A.P.; O’Donnell, K.; Trail, F.; Gardiner, D.M.; Manners, J.M.; Kazan, K. Fusarium pathogenomics. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2013, 67, 399–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sella, L.; Gazzetti, K.; Castiglioni, C.; Schäfer, W.; Favaron, F. Fusarium graminearum possesses virulence factors common to Fusarium head blight of wheat and seedling rot of soybean but differing in their impact on disease severity. Phytopathology 2014, 104, 1201–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sperschneider, J.; Gardiner, D.M.; Thatcher, L.F.; Lyons, R.; Singh, K.B.; Manners, J.M.; Taylor, J.M. Genome-wide analysis in three Fusarium pathogens identifies rapidly evolving chromosomes and genes associated with pathogenicity. Genome Biol. Evol. 2015, 7, 1613–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khaledi, N.; Taheri, P.; Rastegar, M.F. Identification, virulence factors characterization, pathogenicity and aggressiveness analysis of Fusarium spp., causing wheat head blight in Iran. Eur. J. Plant. Pathol. 2017, 147, 897–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.Q.; Lu, X.H.; Sun, M.H.; Guo, R.J.; Van Diepeningen, A.D.; Li, S.D. Transcriptome analysis of virulence-differentiated Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. cucumerinum isolates during cucumber colonisation reveals pathogenicity profiles. BMC Genom. 2019, 20, 570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nei, M.; Kumar, S. Molecular Evolution and Phylogenetics; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Peterson, D.; Filipski, A.; Kumar, S. MEGA6: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013, 30, 2725–2729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kryazhimskiy, S.; Plotkin, J.B. The population genetics of dN/dS. PLoS Genet. 2008, 4, e1000304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donnell, K.; Sutton, D.A.; Rinaldi, M.G.; Sarver, B.A.; Balajee, S.A.; Schroers, H.J.; Summerbell, R.C.; Robert, V.A.; Crous, P.W.; Zhang, N.; et al. Internet-accessible DNA sequence database for identifying fusaria from human and animal infections. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2010, 48, 3708–3718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Xiao, M.; Kong, F.; Chen, S.; Dou, H.T.; Sorrell, T.; Li, R.Y.; Xu, Y.C. Accurate and practical identification of 20 Fusarium species by seven-locus sequence analysis and reverse line blot hybridization, and an in vitro antifungal susceptibility study. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2011, 49, 1890–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donnell, K.; Ward, T.J.; Geiser, D.M.; Kistler, H.C.; Aoki, T. Genealogical concordance between the mating type locus and seven other nuclear genes supports formal recognition of nine phylogenetically distinct species within the Fusarium graminearum clade. Fung. Genet. Biol. 2004, 41, 600–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiser, D.M.; Lewis Ivey, M.L.; Hakiza, G.; Juba, J.H.; Miller, S.A. Gibberella xylarioides (anamorph: Fusarium xylarioides), a causative agent of coffee wilt disease in Africa, is a previously unrecognized member of the G. fujikuroi species complex. Mycologia 2005, 97, 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donnell, K.; Kistler, H.C.; Tacke, B.K.; Casper, H.H. Gene genealogies reveal global phylogeographic structure and reproductive isolation among lineages of Fusarium graminearum, the fungus causing wheat scab. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 7905–7910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Donnell, K.; Nirenberg, H.I.; Aoki, T.; Cigelnik, E. A multigene phylogeny of the Gibberella fujikuroi species complex: Detection of additional phylogenetically distinct species. Mycoscience 2000, 41, 61–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Li, Q.; Liu, Z.; Surendra, A.; Pan, Y.; Li, Y.; Zaharia, L.I.; Ouellet, T.; Fobert, P.R. Integrated transcriptome and hormone profiling highlight the role of multiple phytohormone pathways in wheat resistance against Fusarium head blight. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0207036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Diepeningen, A.D.; Al-Hatmi, A.M.; Brankovics, B.; de Hoog, G.S. Taxonomy and clinical spectra of Fusarium species: Where do we stand in 2014? Curr. Clin. Microbiol. Rep. 2014, 1, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Liu, X.; Li, B.; Ma, Z. Characterization of sterol demethylation inhibitor-resistant isolates of Fusarium asiaticum and F. graminearum collected from wheat in China. Phytopathology 2009, 99, 487–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Délye, C.; Bousset, L.; Corio-Costet, M.F. PCR cloning and detection of point mutations in the eburicol 14a-demethylase (CYP51) gene from Erysiphe graminis f. sp. hordei, a “recalcitrant” fungus. Curr Genet. 1998, 34, 399–403. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, C.X.; Schnabel, G. The cytochrome P450 lanosterol 14α-demethylase gene is a demethylation inhibitor fungicide resistance determinant in Monilinia fructicola field isolates from Georgia. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2008, 74, 359–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cools, H.J.; Fraaije, B.A. Are azole fungicides losing ground against Septoria wheat disease? Resistance mechanisms in Mycosphaerella graminicola. Pest. Manag. Sci. 2008, 64, 681–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perea, S.; López-Ribot, J.L.; Kirkpatrick, W.R.; McAtee, R.K.; Santillán, R.A.; Martínez, M.; Calabrese, D.; Sanglard, D.; Patterson, T.F. Prevalence of molecular mechanisms of resistance to azole antifungal agents in Candida albicans strains displaying high-level fluconazole resistance isolated from human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2001, 45, 2676–2684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellado, E.; Garcia-Effron, G.; Alcazar-Fuoli, L.; Melchers, W.J.; Verweij, P.E.; Cuenca-Estrella, M.; Rodriguez-Tudela, J.L. A new Aspergillus fumigatus resistance mechanism conferring in vitro cross-resistance to azole antifungals involves a combination of CYP51A alterations. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2007, 51, 1897–1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cools, H.J.; Parker, J.E.; Kelly, D.E.; Lucas, J.A.; Fraaije, B.A.; Kelly, S.L. Heterologous expression of mutated eburicol 14α-demethylase (CYP51) proteins of Mycosphaerella graminicola to assess effects on azole fungicide sensitivity and intrinsic protein function. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2010, 76, 2866–2872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cools, H.J.; Bayon, C.; Atkins, S.; Lucas, J.A.; Fraaije, B.A. Overexpression of the sterol 14α-demethylase gene (MgCYP51) in Mycosphaerella graminicola isolates confers a novel azole fungicide sensitivity phenotype. Pest. Manag. Sci. 2012, 68, 1034–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fungicide Resistance Action Committee. FRAC Code List 2018: List of Plant Pathogenic Organisms Resistant to Disease Control Agents. Available online: https://www.frac.info/docs/default-source/publications/list-of-resistant-plant-pathogens/list-of-resistant-plant-pathogenic-organisms_may-2018.pdf?sfvrsn=a2454b9a_2. (accessed on 26 February 2019).

- Chowdhary, A.; Kathuria, S.; Xu, J.; Meis, J.F. Emergence of azole-resistant Aspergillus fumigatus strains due to agricultural azole use creates an increasing threat to human health. PLoS Pathog. 2013, 9, e1003633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faria-Ramos, I.; Farinha, S.; Neves-Maia, J.; Tavares, P.R.; Miranda, I.M.; Estevinho, L.M.; Pina-Vaz, C.; Rodrigues, A.G. Development of cross-resistance by Aspergillus fumigatus to clinical azoles following exposure to prochloraz, an agricultural azole. BMC Microbiol. 2014, 14, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berger, S.; El Chazli, Y.; Babu, A.F.; Coste, A.T. Azole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus: A consequence of antifungal use in agriculture? Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brunner, P.C.; Stefansson, T.S.; Fountaine, J.; Richina, V.; McDonald, B.A. A global analysis of CYP51 diversity and azole sensitivity in Rhynchosporium commune. Phytopathology 2016, 106, 355–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawkins, N.J.; Cools, H.J.; Sierotzki, H.; Shaw, M.W.; Knogge, W.; Kelly, S.L.; Fraaije, B.A. Paralog re-emergence: A novel, historically contingent mechanism in the evolution of antimicrobial resistance. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2014, 31, 1793–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lynch, M.; Conery, J.S. The evolutionary fate and consequences of duplicate genes. Science 2000, 290, 1151–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hileman, L.C.; Baum, D.A. Why do paralogs persist? Molecular evolution of Cycloidea and related floral symmetry genes in Antirrhineae (Veronicaceae). Mol. Biol. Evol. 2003, 20, 591–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trachana, K.; Jensen, L.J.; Bork, P. Evolution and regulation of cellular periodic processes: A role for paralogues. EMBO Rep. 2010, 11, 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; O’Donnell, K.; Sutton, D.A.; Nalim, F.A.; Summerbell, R.C.; Padhye, A.A.; Geiser, D.M. Members of the Fusarium solani species complex that cause infections in both humans and plants are common in the environment. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2006, 44, 2186–2190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Donnell, K.; Kistler, H.C.; Cigelnik, E.; Ploetz, R.C. Multiple evolutionary origins of the fungus causing Panama disease of banana: Concordant evidence from nuclear and mitochondrial gene genealogies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 2044–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katoh, K.; Rozewicki, J.; Yamada, K.D. MAFFT online service: Multiple sequence alignment, interactive sequence choice and visualization. Brief. Bioinform. 2017, 20, 1160–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, L.; Hyde, K.D.; Taylor, P.W.J.; Weir, B.; Waller, J.; Abang, M.M.; Zhang, J.Z.; Yang, Y.L.; Phoulivong, S.; Liu, Z.Y.; et al. A polyphasic approach for studying Colletotrichum. Fungal Divers. 2009, 39, 183–204. [Google Scholar]

- Prihastuti, H.; Cai, L.; Chen, H.; McKenzie, E.H.C.; Hyde, K.D. Characterization of Colletotrichum species associated with coffee berries in northern Thailand. Fungal Divers. 2009, 39, 89–109. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, T.A. BioEdit: A user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic Acids Symp. Ser. 1999, 41, 95–98. [Google Scholar]

- Guindon, S.; Dufayard, J.F.; Lefort, V.; Anisimova, M.; Hordijk, W.; Gascuel, O. New algorithms and methods to estimate maximum-likelihood phylogenies: Assessing the performance of PhyML 3.0. Syst. Biol. 2010, 593, 307–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.Q.; Liu, Y.H.; Zhu, G.N. Detection and characterization of benzimidazole resistance of Botrytis cinerea in greenhouse vegetables. Eur. J. Plant. Pathol. 2010, 126, 509–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, M.R. Sterol-inhibiting fungicides: Effects on sterol biosynthesis and sites of action. Plant. Dis. 1981, 65, 986–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Ortuño, D.; Loza-Reyes, E.; Atkins, S.L.; Fraaije, B.A. The CYP51C gene, a reliable marker to resolve interspecific phylogenetic relationships within the Fusarium species complex and a novel target for species-specific PCR. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2010, 1442, 301–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozas, J.; Sánchez-DelBarrio, J.C.; Messeguer, X.; Rozas, R. DnaSP, DNA polymorphism analyses by the coalescent and other methods. Bioinformatics 2003, 19, 2496–2497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Librado, P.; Rozas, J. DnaSP v5: A software for comprehensive analysis of DNA polymorphism data. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 1451–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| CAM | EF1a | RPB2 | NRRL | FIESC Haplotype | Host | Country | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GQ505575 | GQ505664 | GQ505482 | 43637 | 1-a | dog | Pennsylvania | [14] |

| GQ505582 | GQ505671 | GQ505849 | 45996 | 1-a | human sinus | New York | [14] |

| GQ505578 | GQ505667 | GQ505845 | 43640 | 1-a | dog nose | Texas | [14] |

| GQ505551 | GQ505639 | GQ505817 | 34039 | 1-b | human | Connecticut | [14] |

| GQ505548 | GQ505636 | GQ505814 | 34034 | 1-c | human leg | Arizona | [14] |

| GQ505563 | GQ505651 | GQ505829 | 36401 | 2-a | cotton | Mozambique | [14] |

| GQ505564 | GQ505652 | GQ505830 | 36448 | 2-b | Phaseolus vulgaris seed | Sudan | [14] |

| GQ505824 | GQ505646 | GQ505558 | 36318 | 3-a | unknown | unknown | [14] |

| GQ505560 | GQ505648 | GQ505826 | 36323 | 3-a | cotton yarn | England | [14] |

| GQ505514 | GQ505602 | GQ505780 | 28029 | 3-b | Human eye | California | [14] |

| GQ505505 | GQ505593 | GQ505771 | 20423 | 4-a | Lizard skin | India | [14] |

| GQ505555 | GQ505643 | GQ505821 | 36123 | 4-b | unknown | unknown | [14] |

| GQ505531 | GQ505619 | GQ505797 | 32871 | 5-a | human abscess | Texas | [14] |

| GQ505547 | GQ505635 | GQ505813 | 34032 | 5-a | human abscess | Texas | [14] |

| GQ505550 | GQ505638 | GQ505816 | 34037 | 5-b | human abscess | Colorado | [14] |

| GQ505581 | GQ505670 | GQ505848 | 45995 | 5-b | human abscess | Colorado | [14] |

| GQ505509 | GQ505597 | GQ505775 | 25795 | 5-c | Disphyma seed | Germany | [14] |

| GQ505549 | GQ505637 | GQ505815 | 34035 | 5-d | human sinus | Colorado | [14] |

| GQ505572 | GQ505661 | GQ505839 | 43623 | 5-e | human maxillary sinus | Colorado | [14] |

| GQ505583 | GQ505672 | GQ505850 | 45997 | 5-f | human sinus | Colorado | [14] |

| GQ505576 | GQ505665 | GQ505843 | 43638 | 6-a | Manatee | Florida | [14] |

| GQ505579 | GQ505668 | GQ505846 | 43694 | 6-a | human eye | Texas | [14] |

| GQ505584 | GQ505673 | GQ505851 | 45998 | 6-b | human toe | Texas | [14] |

| GQ505536 | GQ505642 | GQ505802 | 32997 | 7-a | human toe nail | Colorado | [14] |

| GQ505500 | GQ505588 | GQ505766 | 5537 | 8-a | Fescue hay | Missouri | [14] |

| N/A | GQ505658 | GQ505836 | 43498 | 8-b | human eye | Pennsylvania | [14] |

| GQ505566 | GQ505654 | GQ505832 | 36478 | 9-a | Pasture soil | Australia | [14] |

| GQ505517 | GQ505604 | GQ505783 | 29134 | 9-a | Pasture soil | Australia | [14] |

| GQ505504 | GQ505592 | GQ505770 | 13402 | 9-b | Pine soil | Australia | [14] |

| GQ505513 | GQ505601 | GQ505779 | 26922 | 9-c | soil | France | [14] |

| GQ505498 | GQ505586 | GQ505764 | 3020 | 10-a | unknown | unknown | [14] |

| GQ505499 | GQ505587 | GQ505765 | 3214 | 10-a | unknown | unknown | [14] |

| GQ505561 | GQ505649 | GQ505827 | 36372 | 11-a | air | Netherlands | [14] |

| GQ505501 | GQ505589 | GQ505767 | 6548 | 12-a | Wheat | Germany | [14] |

| GQ505512 | GQ505600 | GQ505778 | 26921 | 12-a | Wheat | Germany | [14] |

| GQ505518 | GQ505606 | GQ505784 | 31011 | 12-a | Thuja sp. | Germany | [14] |

| GQ505557 | GQ505645 | GQ505823 | 36269 | 12-b | Pinusnigra seedling | Croatia | [14] |

| GQ505562 | GQ505650 | GQ505828 | 36392 | 12-c | seedling | Germany | [14] |

| GQ505573 | GQ505662 | GQ505840 | 43635 | 13-a | horse | Nebraska | [14] |

| GQ505511 | GQ505599 | GQ505777 | 26419 | 14-a | soil | Germany | [14] |

| GQ505556 | GQ505644 | GQ505822 | 36136 | 14-a | unknown | unknown | [14] |

| GQ505559 | GQ505647 | GQ505825 | 36321 | 14-a | soil | Netherlands | [14] |

| GQ595565 | GQ505653 | GQ505831 | 36466 | 14-a | potato peel | Denmark | [14] |

| GQ505506 | GQ505594 | GQ505772 | 20697 | 14-b | beet | Chile | [14] |

| GQ505574 | GQ505663 | GQ505841 | 43636 | 14-c | dog | Texas | [14] |

| GQ505521 | GQ505609 | GQ505787 | 32175 | 15-a | human septum | Texas | [14] |

| GQ505542 | GQ505630 | GQ505808 | 34006 | 15-a | human eye | Texas | [14] |

| GQ505543 | GQ505631 | GQ505809 | 34007 | 15-a | human septum | Texas | [14] |

| GQ505546 | GQ505634 | GQ505812 | 34011 | 15-a | human septum | Texas | [14] |

| GQ505570 | GQ505659 | GQ505837 | 43619 | 15-a | human finger | Texas | [14] |

| GQ505523 | GQ505611 | GQ505789 | 32182 | 15-b | human blood | Texas | [14] |

| GQ505519 | GQ505607 | GQ505785 | 31160 | 15-c | human lung | Texas | [14] |

| GQ505522 | GQ505610 | GQ505788 | 32181 | 15-c | human blood | Oklahoma | [14] |

| GQ505530 | GQ505618 | GQ505796 | 32869 | 15-c | human cancer patient | Texas | [14] |

| GQ505533 | GQ505621 | GQ505799 | 32994 | 15-c | human ethmoid sinus | Texas | [14] |

| GQ505534 | GQ505622 | GQ505800 | 32995 | 15-c | human sinus | Texas | [14] |

| GQ505535 | GQ505623 | GQ505801 | 32996 | 15-c | human leg wound | Texas | [14] |

| GQ505545 | GQ505633 | GQ505811 | 34010 | 15-c | human maxillary sinus | Texas | [14] |

| GQ505571 | GQ505660 | GQ505838 | 43622 | 15-c | human lung | Texas | [14] |

| GQ505544 | GQ505632 | GQ505810 | 34008 | 15-d | human lung | Texas | [14] |

| GQ505537 | GQ505625 | GQ505803 | 34001 | 15-e | human foot wound | Texas | [14] |

| GQ505540 | GQ505628 | GQ505806 | 34004 | 16-a | human BAL | Texas | [14] |

| GQ505552 | GQ505640 | GQ505818 | 34056 | 16-b | human bronchial wash | Illinois | [14] |

| GQ505553 | GQ505641 | GQ505819 | 34059 | 16-c | human blood | Illinois | [14] |

| GQ505580 | GQ505669 | GQ505847 | 43730 | 16-c | Contact lens | Mississippi | [14] |

| GQ505525 | GQ505613 | GQ505791 | 32864 | 17-a | human | Texas | [14] |

| GQ505567 | GQ505655 | GQ505833 | 36548 | 17-b | Banana | Congo | [14] |

| GQ505554 | GQ505642 | GQ505820 | 34070 | 17-c | Tortoise | Illinois | [14] |

| GQ505520 | GQ505608 | GQ505786 | 31167 | 18-a | human septum | Texas | [14] |

| GQ505524 | GQ505612 | GQ505790 | 32522 | 18-b | human diabetic cellulitis | Illinois | [14] |

| GQ505577 | GQ505666 | GQ505844 | 43639 | 19-a | Manatee | Florida | [14] |

| GQ505539 | GQ505627 | GQ505805 | 34003 | 20-a | human septum | Texas | [14] |

| GQ505568 | GQ505656 | GQ505834 | 36575 | 20-b | Juniperus chinensis leaf | Hawaii | [14] |

| GQ505502 | GQ505590 | GQ505768 | 13335 | 21-a | alfalfa | Australia | [14] |

| GQ505526 | GQ505614 | GQ505792 | 32865 | 21-b | human endocarditis | Brazil | [14] |

| GQ505538 | GQ505626 | GQ505804 | 34002 | 22-a | human ethmoid sinus | Texas | [14] |

| GQ505527 | GQ505615 | GQ505793 | 32866 | 23-a | human cancer patient | Texas | [14] |

| GQ505528 | GQ505618 | GQ505794 | 32867 | 23-a | human | Texas | [14] |

| GQ505503 | GQ505591 | GQ505769 | 13379 | 23-b | Oryza sativa | India | [14] |

| GQ505541 | GQ505629 | GQ505807 | 34005 | 24-a | human intravitral fluid | Minnesota | [14] |

| GQ505569 | GQ505657 | GQ505835 | 43297 | 24-b | Saprotina rhizomes | Connecticut | [14] |

| GQ505508 | GQ505596 | GQ505774 | 22244 | 25-a | rice | China | [14] |

| GQ505532 | GQ505620 | GQ505798 | 32993 | 25-b | human nasal tissue | Texas | [14] |

| GQ505529 | GQ505617 | GQ505795 | 32868 | 25-c | human blood | Texas | [14] |

| GQ505510 | GQ505598 | GQ505776 | 26417 | 26-a | leaf litter | Cuba | [14] |

| GQ505516 | GQ505604 | GQ505782 | 28714 | 26-b | Acacia sp. Branch | Costa Rica | [14] |

| GQ505507 | GQ505595 | GQ505773 | 20722 | 27-a | Chrysanthemum sp. | Kenya | [14] |

| GQ505515 | GQ505603 | GQ505781 | 28577 | 28-a | grave stone | Romania | [14] |

| GQ505585 | GQ505674 | GQ505852 | 13459 | N/A | plant debris | South Africa | [14] |

| Sample | MLST Type | Growth Inhibition (%) 1 | EC50 (µg/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 15-a | 52.94 | 9.1 |

| 13 | 15-a | 49.02 | 10.4 |

| 15 | 15-a | 54.90 | 7.8 |

| 20 | 15-a | 60.61 | 5.5 |

| 22 | 15-a | 52.38 | 9.5 |

| 28 | 15-a | 43.48 | 13.3 |

| 31 | 15-a | 55.56 | 7.7 |

| 33 | 15-a | 62.86 | 4.7 |

| 36 | 15-a | 52.94 | 9.1 |

| 2 | 16-a | 48.39 | 10.1 |

| 5 | 16-a | 42.42 | 13.8 |

| 6 | 16-a | 56.41 | 7.2 |

| 14 | 16-a | 58.82 | 6.3 |

| 18 | 16-a | 39.39 | 10.8 |

| 21 | 16-a | 64.29 | 4.3 |

| 25 | 16-a | 64.29 | 4.3 |

| 26 | 16-a | 58.82 | 6.4 |

| 27 | 16-a | 62.86 | 4.7 |

| 29 | 16-a | 31.58 | 18.4 |

| 32 | 16-a | 35.00 | 17.1 |

| 35 | 16-a | 48.39 | 10.9 |

| 38 | 16-a | 42.42 | 13.8 |

| 39 | 16-a | 56.41 | 7.7 |

| 40 | 16-a | 52.94 | 8.7 |

| 41 | 16-a | 49.02 | 10.5 |

| 42 | 16-a | 50.98 | 11.5 |

| 47 | 16-a | 39.39 | 10.8 |

| 49 | 16-a | 45.45 | 5.5 |

| 50 | 16-a | 53.85 | 12.4 |

| 51 | 16-a | 49.02 | 10.5 |

| Sample | MLST Type | Growth Inhibition (%) 1 | EC50 (µg/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 56 | 26-a | 80.00 | 1.2 |

| 57 | 26-a | 82.05 | 1.2 |

| 58 | 26-a | 80.00 | 1.2 |

| 59 | 26-a | 80.56 | 1.5 |

| 60 | 26-a | 81.58 | 2.3 |

| 61 | 26-a | 80.56 | 5.8 |

| 62 | 26-a | 80.00 | 1.9 |

| 63 | 26-a | 80.00 | 1.3 |

| 64 | 26-a | 80.00 | 2.7 |

| 65 | 26-a | 80.00 | 3.2 |

| 66 | 26-a | 80.56 | 1.9 |

| 67 | 26-a | 80.00 | 1.6 |

| 52 | Equiseti | 100.00 | 2.6 |

| 53 | Equiseti | 100.00 | 2.6 |

| 54 | Equiseti | 100.00 | 3.6 |

| 55 | Equiseti | 100.00 | 1.8 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Villafana, R.T.; Rampersad, S.N. Three-Locus Sequence Identification and Differential Tebuconazole Sensitivity Suggest Novel Fusarium equiseti Haplotype from Trinidad. Pathogens 2020, 9, 175. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens9030175

Villafana RT, Rampersad SN. Three-Locus Sequence Identification and Differential Tebuconazole Sensitivity Suggest Novel Fusarium equiseti Haplotype from Trinidad. Pathogens. 2020; 9(3):175. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens9030175

Chicago/Turabian StyleVillafana, Ria T., and Sephra N. Rampersad. 2020. "Three-Locus Sequence Identification and Differential Tebuconazole Sensitivity Suggest Novel Fusarium equiseti Haplotype from Trinidad" Pathogens 9, no. 3: 175. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens9030175

APA StyleVillafana, R. T., & Rampersad, S. N. (2020). Three-Locus Sequence Identification and Differential Tebuconazole Sensitivity Suggest Novel Fusarium equiseti Haplotype from Trinidad. Pathogens, 9(3), 175. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens9030175