Prevalence, Intensity, and Correlates of Soil-Transmitted Helminth Infections among School Children after a Decade of Preventive Chemotherapy in Western Rwanda

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Prevalence and Intensities of STH Infections

- ○

- T. trichiura: Light (1–999 epg), Moderate (1000–9999 epg), Heavy (≥10,000 epg).

- ○

- A. lumbricoides: Light (1–4999 epg), Moderate (5000–49,999 epg), Heavy (≥50,000 epg).

- ○

- Hookworm: Light (1–1999 epg), Moderate (2000–3999 epg), Heavy (≥4000 epg).

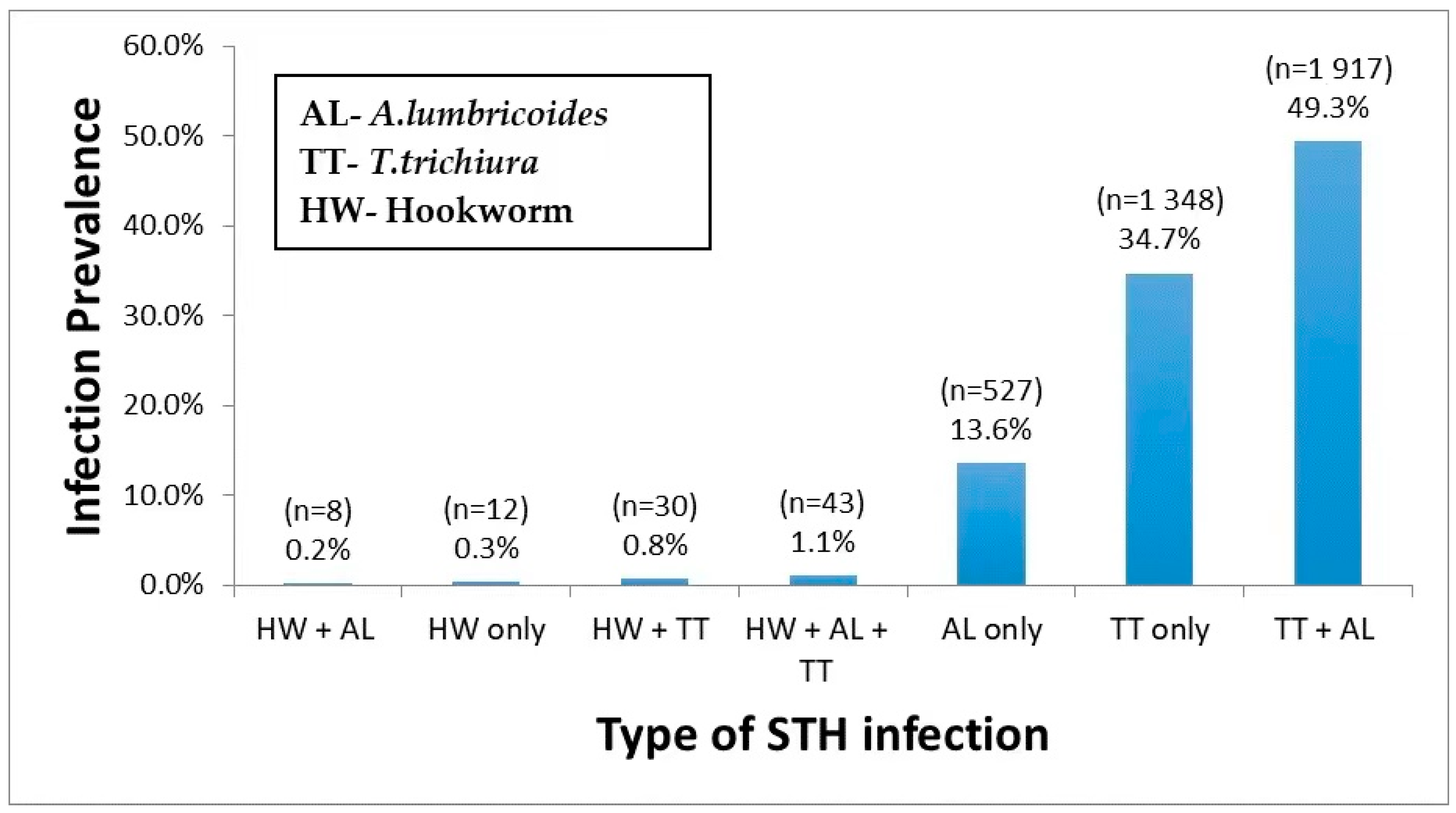

2.2. Prevalence of Single and Multiple STH Parasite Coinfections

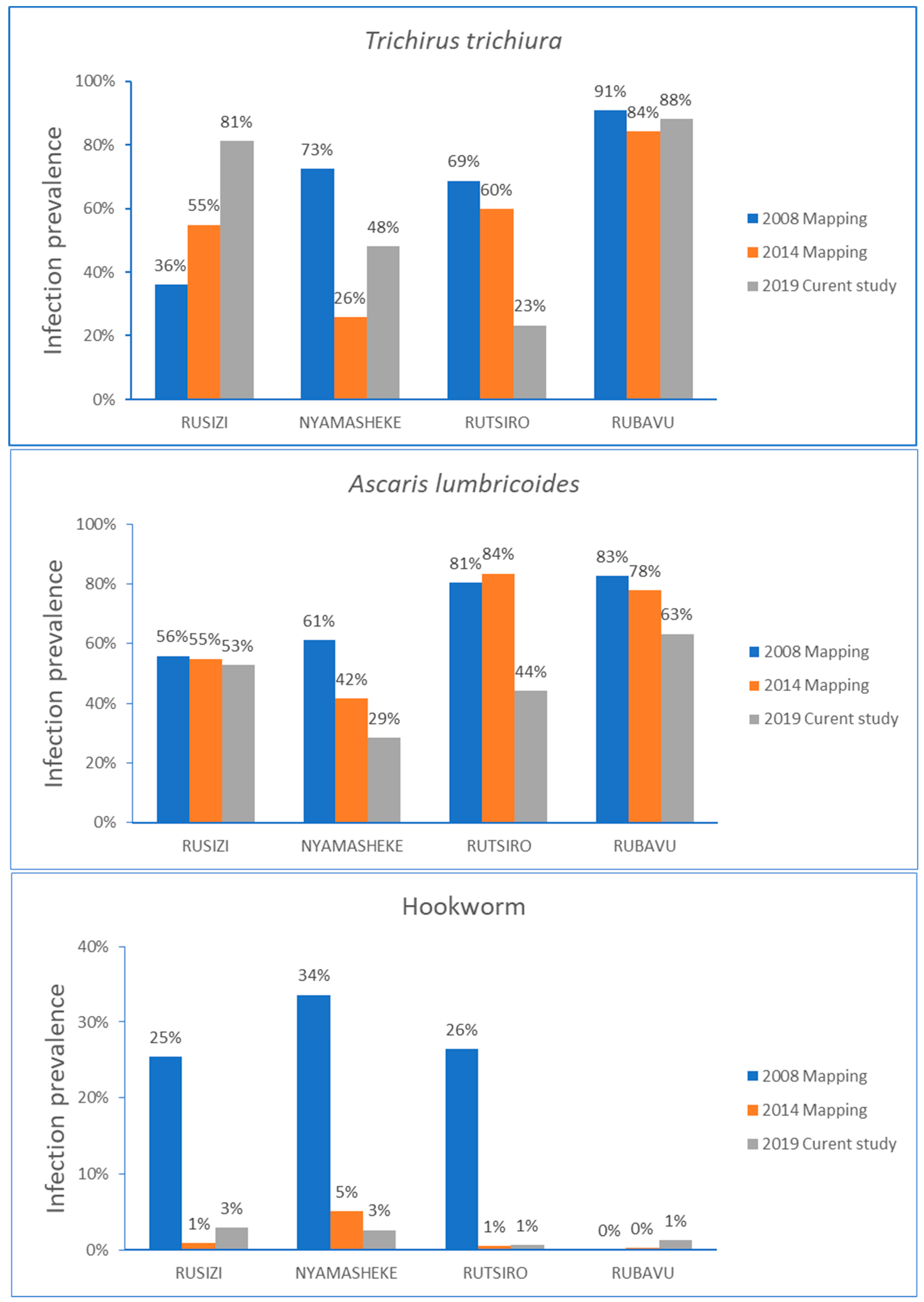

2.3. Change in Prevalence of STH Infection Overtime among Study Districts

2.4. Correlates of STH Infections

2.5. Risk Factors Associated with Infection Intensity

2.6. Risk Factors Associated with Any STH Infections

2.7. Factors Associated with Hookworms Infection

2.8. Factors Associated with Ascaris Lumbricoides Infection

2.9. Factors Associated with Trichuris Trichiura Infections

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

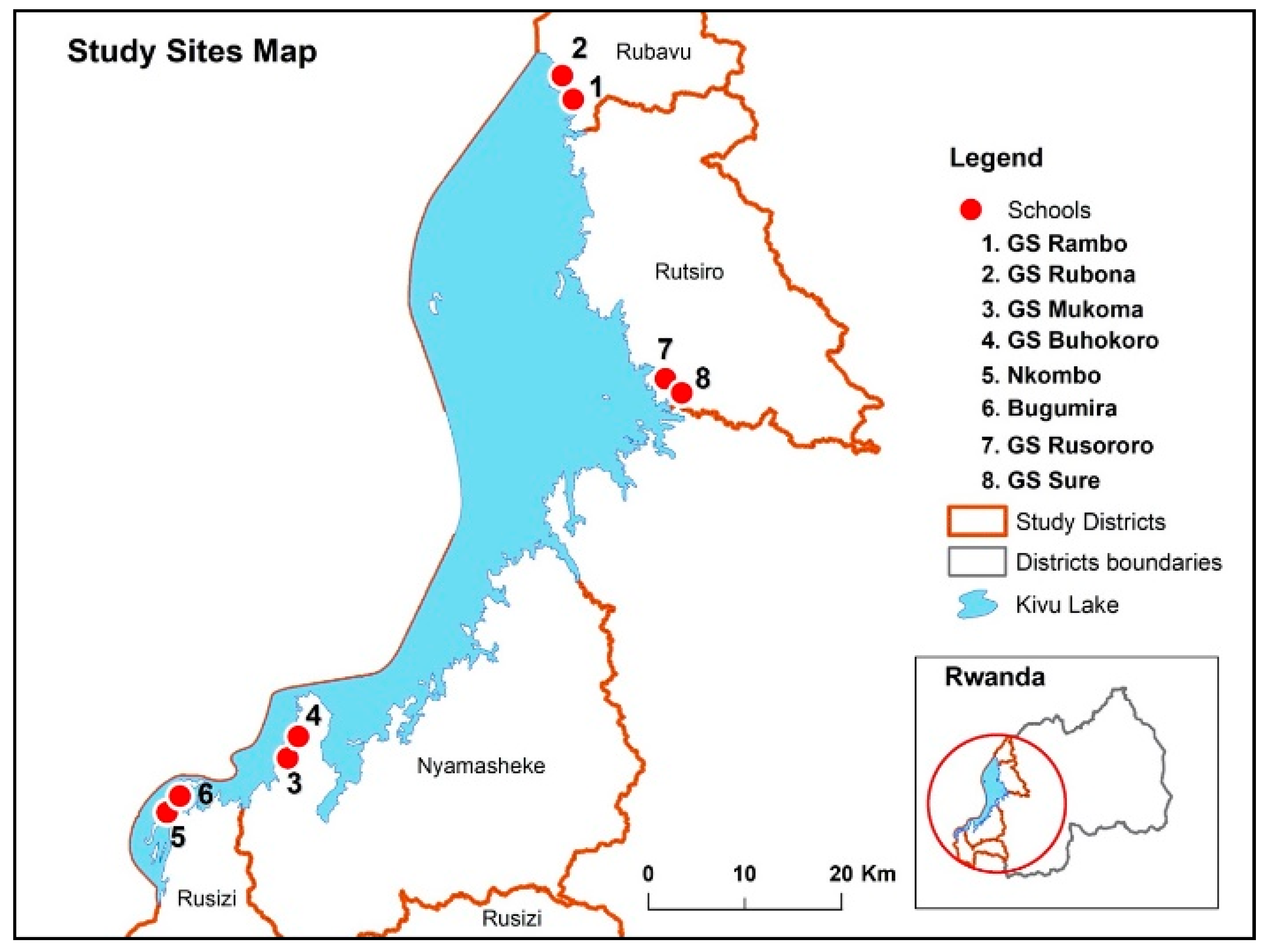

4.1. Study Area, Population, and Design

4.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

4.3. Data Collection

4.4. Screening for STH Parasite Species

4.5. Data Processing and Statistical Analysis

4.6. Ethical Consideration

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Soil-Transmitted Helminth Infections. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/soil-transmitted-helminth-infections (accessed on 11 November 2020).

- Pullan, R.L.; Smith, J.L.; Jasrasaria, R.; Brooker, S.J. Global numbers of infection and disease burden of soil transmitted helminth infections in 2010. Parasites Vectors 2014, 7, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parija, S.C.; Chidambaram, M.; Mandal, J. Epidemiology and clinical features of soil-transmitted helminths. Trop. Parasitol. 2017, 7, 81–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Worrell, C.M.; Wiegand, R.E.; Davis, S.M.; Odero, K.O.; Blackstock, A.; Cuellar, V.M.; Njenga, S.M.; Montgomery, J.M.; Roy, S.L.; Fox, L.M. A Cross-Sectional Study of Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene-Related Risk Factors for Soil-Transmitted Helminth Infection in Urban School- and Preschool-Aged Children in Kibera, Nairobi. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0150744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, A.; Al-Mekhlafi, H.M.; Al-Adhroey, A.H.; Ithoi, I.; Abdulsalam, A.M.; Surin, J. The nutritional impacts of soil-transmitted helminths infections among Orang Asli schoolchildren in rural Malaysia. Parasites Vectors 2012, 5, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Assembly. Schistosomiasis and Soil-Transmitted Helminth Infections. World Health Assembly 54.19. Available online: https://www.who.int/neglected_diseases/mediacentre/WHA_54.19_Eng.pdf (accessed on 8 November 2020).

- World Health Organization. Preventive Chemotherapy in Human Helminthiasis. Coordinated Use of Anthelminthic Drugs in Control Interventions: A Manual for Health Professionals and Programme Managers. Available online: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/43545/9241547103_eng.pdf;jsessionid=47850DFF1D48F2074B6B75372938AD9A?sequence=1 (accessed on 7 November 2020).

- World Health Organization. Soil-Transmitted Helminthiases: Eliminating as Public Health Problem Soil-Transmitted Helminthiases in Children: Progress Report 2001–2010 and Strategic Plan 2011–2020. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/44804 (accessed on 7 November 2020).

- Rujeni, N.; Morona, D.; Ruberanziza, E.; Mazigo, H.D. Schistosomiasis and soil-transmitted helminthiasis in Rwanda: An update on their epidemiology and control. Infect. Dis. Poverty 2017, 6, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruxin, J.; Negin, J. Removing the neglect from neglected tropical diseases: The Rwandan experience 2008–2010. Glob. Public Health 2012, 7, 812–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karema, C.; Fenwick, A.; Colley, D.G. Mapping of Schistosomiasis and Soil-Transmitted Helminthiasis in Rwanda 2014—Mapping Survey Report; Rwanda Biomedical Center: Kigali, Rwanda, 2015.

- Gabrielli, A.F.; Montresor, A.; Chitsulo, L.; Engels, D.; Savioli, L. Preventive chemotherapy in human helminthiasis: Theoretical and operational aspects. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2011, 105, 683–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO; Montresor, A.; Crompton, D.W.T.; Hall, A.; Bundy, D.A.P.; Savioli, L. Guidelines for the Evaluation of Soil-Transmitted Helminthiasis and Schistosomiasis at Community Level: A Guide for Managers of Control Programmes; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1998; Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/63821/WHO_CTD_SIP_98.1.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 14 November 2020).

- WHO. AnthroPlus for Personal Computers Manual: Software for Assessing Growth of the World’s Children and Adolescents. Available online: http://www.who.int/growthref/tools/en/ (accessed on 14 November 2020).

- Rwanda Demographic and Health Survey 2014–2015. Available online: https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR316/FR316.pdf (accessed on 13 November 2020).

- Mnkugwe, R.H.; Minzi, O.S.; Kinung’hi, S.M.; Kamuhabwa, A.A.; Aklillu, E. Prevalence and correlates of intestinal schistosomiasis infection among school-aged children in North-Western Tanzania. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0228770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degarege, A.; Animut, A.; Medhin, G.; Legesse, M.; Erko, B. The association between multiple intestinal helminth infections and blood group, anaemia and nutritional status in human populations from Dore Bafeno, southern Ethiopia. J. Helminthol. 2014, 88, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, M.C.; Chard, A.N.; Nikolay, B.; Garn, J.V.; Okoyo, C.; Kihara, J.; Njenga, S.M.; Pullan, R.L.; Brooker, S.J.; Mwandawiro, C.S. Associations between school- and household-level water, sanitation and hygiene conditions and soil-transmitted helminth infection among Kenyan school children. Parasites Vectors 2015, 8, 412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bethony, J.; Brooker, S.; Albonico, M.; Geiger, S.M.; Loukas, A.; Diemert, D.; Hotez, P.J. Soil-transmitted helminth infections: Ascariasis, trichuriasis, and hookworm. Lancet 2006, 367, 1521–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebreyesus, T.D.; Tadele, T.; Mekete, K.; Barry, A.; Gashaw, H.; Degefe, W.; Tadesse, B.T.; Gerba, H.; Gurumurthy, P.; Makonnen, E.; et al. Prevalence, Intensity, and Correlates of Schistosomiasis and Soil-Transmitted Helminth Infections after Five Rounds of Preventive Chemotherapy among School Children in Southern Ethiopia. Pathogens 2020, 9, 920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Health (MOH). Rwanda’s Neglected Tropical Diseases Strategic Plan 2019–2024. Available online: https://rbc.gov.rw/fileadmin/user_upload/guide2019/guide2019/RWANDA%20NTD%20STRATEGIC%20PLAN%202019-2024.pdf (accessed on 13 November 2020).

- Moser, W.; Schindler, C.; Keiser, J. Efficacy of recommended drugs against soil transmitted helminths: Systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMJ 2017, 358, j4307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muller, I.; Beyleveld, L.; Gerber, M.; Puhse, U.; du Randt, R.; Utzinger, J.; Zondie, L.; Walter, C.; Steinmann, P. Low efficacy of albendazole against Trichuris trichiura infection in schoolchildren from Port Elizabeth, South Africa. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2016, 110, 676–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, A.; Namwanje, H.; Nejsum, P.; Roepstorff, A.; Thamsborg, S.M. Albendazole and mebendazole have low efficacy against Trichuristrichiura in school-age children in Kabale District, Uganda. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2009, 103, 443–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, C.; Coulibaly, J.T.; Schulz, J.D.; N’Gbesso, Y.; Hattendorf, J.; Keiser, J. Efficacy and safety of ascending dosages of albendazole against Trichuris trichiura in preschool-aged children, school-aged children and adults: A multi-cohort randomized controlled trial. EClinicalMedicine 2020, 22, 100335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, W.; Coulibaly, J.T.; Ali, S.M.; Ame, S.M.; Amour, A.K.; Yapi, R.B.; Albonico, M.; Puchkov, M.; Huwyler, J.; Hattendorf, J.; et al. Efficacy and safety of tribendimidine, tribendimidine plus ivermectin, tribendimidine plus oxantel pamoate, and albendazole plus oxantel pamoate against hookworm and concomitant soil-transmitted helminth infections in Tanzania and Cote d’Ivoire: A randomised, controlled, single-blinded, non-inferiority trial. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2017, 17, 1162–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, L.; Palmeirim, M.S.; Ame, S.M.; Ali, S.M.; Puchkov, M.; Huwyler, J.; Hattendorf, J.; Keiser, J. Efficacy and Safety of Ascending Dosages of Moxidectin and Moxidectin-albendazole Against Trichuris trichiura in Adolescents: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020, 70, 1193–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krucken, J.; Fraundorfer, K.; Mugisha, J.C.; Ramunke, S.; Sifft, K.C.; Geus, D.; Habarugira, F.; Ndoli, J.; Sendegeya, A.; Mukampunga, C.; et al. Reduced efficacy of albendazole against Ascaris lumbricoides in Rwandan schoolchildren. Int. J. Parasitol. Drugs Drug Resist. 2017, 7, 262–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruberanziza, E.; Kabera, M.; Ortu, G.; Kanobana, K.; Mupfasoni, D.; Ruxin, J.; Fenwick, A.; Nyatanyi, T.; Karema, C.; Munyaneza, T.; et al. Nkombo Island: The Most Important Schistosomiasis mansoni Focus in Rwanda. Am. J. Life Sci. 2015, 3, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okoyo, C.; Campbell, S.J.; Williams, K.; Simiyu, E.; Owaga, C.; Mwandawiro, C. Prevalence, intensity and associated risk factors of soil-transmitted helminth and schistosome infections in Kenya: Impact assessment after five rounds of mass drug administration in Kenya. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2020, 14, e0008604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fimbo, A.M.; Minzi, O.M.S.; Mmbando, B.P.; Barry, A.; Nkayamba, A.F.; Mwamwitwa, K.W.; Malishee, A.; Seth, M.D.; Makunde, W.H.; Gurumurthy, P.; et al. Prevalence and Correlates of Lymphatic Filariasis Infection and Its Morbidity Following Mass Ivermectin and Albendazole Administration in Mkinga District, North-Eastern Tanzania. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freeman, M.C.; Akogun, O.; Belizario, V., Jr.; Brooker, S.J.; Gyorkos, T.W.; Imtiaz, R.; Krolewiecki, A.; Lee, S.; Matendechero, S.H.; Pullan, R.L.; et al. Challenges and opportunities for control and elimination of soil-transmitted helminth infection beyond 2020. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2019, 13, e0007201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, S.J.; Savage, G.B.; Gray, D.J.; Atkinson, J.A.; Soares Magalhaes, R.J.; Nery, S.V.; McCarthy, J.S.; Velleman, Y.; Wicken, J.H.; Traub, R.J.; et al. Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene (WASH): A critical component for sustainable soil-transmitted helminth and schistosomiasis control. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2014, 8, e2651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaz Nery, S.; Pickering, A.J.; Abate, E.; Asmare, A.; Barrett, L.; Benjamin-Chung, J.; Bundy, D.A.P.; Clasen, T.; Clements, A.C.A.; Colford, J.M., Jr.; et al. The role of water, sanitation and hygiene interventions in reducing soil-transmitted helminths: Interpreting the evidence and identifying next steps. Parasites Vectors 2019, 12, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. WHO Strengthens Focus on Water, Sanitation and Hygiene to Accelerate Elimination of Neglected Tropical Diseases. Available online: https://www.who.int/water_sanitation_health/events/wash-and-ntd-strategy/en/ (accessed on 13 November 2020).

- Montresor, A.; Mupfasoni, D.; Mikhailov, A.; Mwinzi, P.; Lucianez, A.; Jamsheed, M.; Gasimov, E.; Warusavithana, S.; Yajima, A.; Bisoffi, Z.; et al. The global progress of soil-transmitted helminthiases control in 2020 and World Health Organization targets for 2030. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2020, 14, e0008505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Assessing the Efficacy OF Anthelminthic Drugs Against Schistosomiasis and Soil-Transmitted Helminthiases; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Vercruysse, J.; Albonico, M.; Behnke, J.M.; Kotze, A.C.; Prichard, R.K.; McCarthy, J.S.; Montresor, A.; Levecke, B. Is anthelmintic resistance a concern for the control of human soil-transmitted helminths? Int. J. Parasitol. Drugs Drug Resist. 2011, 1, 14–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mnkugwe, R.H.; Minzi, O.; Kinung’hi, S.; Kamuhabwa, A.; Aklillu, E. Efficacy and safety of praziquantel and dihydroartemisinin piperaquine combination for treatment and control of intestinal schistosomiasis: A randomized, non-inferiority clinical trial. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2020, 14, e0008619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, J.C.; Papaiakovou, M.; Han, K.T.; Chooneea, D.; Bettis, A.A.; Wyine, N.Y.; Lwin, A.M.M.; Maung, N.S.; Misra, R.; Littlewood, D.T.J.; et al. The increased sensitivity of qPCR in comparison to Kato-Katz is required for the accurate assessment of the prevalence of soil-transmitted helminth infection in settings that have received multiple rounds of mass drug administration. Parasites Vectors 2020, 13, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarafder, M.R.; Carabin, H.; Joseph, L.; Balolong, E., Jr.; Olveda, R.; McGarvey, S.T. Estimating the sensitivity and specificity of Kato-Katz stool examination technique for detection of hookworms, Ascaris lumbricoides and Trichuris trichiura infections in humans in the absence of a ‘gold standard’. Int. J. Parasitol. 2010, 40, 399–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Basic Laboratory Methods in Medical Parasitology. Available online: https://www.who.int/malaria/publications/atoz/9241544104_part1/en/ (accessed on 11 November 2020).

| Parasite | Infection Prevalence | Intensity of Infection | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Infection | Light | Moderate | Heavy | ||

| Any STH parasit | 77.7% | ||||

| T. trichuria | 66.8% | 33.2% | 59.7% | 6.9% | 0.2% |

| A. lumbricoides | 49.9% | 50.1% | 36.1% | 12.8% | 1.1% |

| Hookworms | 1.9% | 98.1% | 1.8% | 0 | 0 |

| Variable | STH Positive (n = 3885) | T. trichiura (n = 3338) | A. lumbricoides. (n = 2495) | Hook Worms (n = 93) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | p-Value | n (%) | p-Value | n (%) | p-Value | n (%) | p-Value | ||

| Sex | <0.001 | 0.01 | 0.009 | 0.74 | |||||

| Male | 1874 (80.0) | 1608 (68.6) | 1216 (51.9) | 42 (1.8) | |||||

| Female | 2011 (75.8) | 1730 (65.2) | 1279 (48.2) | 51 (1.9) | |||||

| Age categories | 0.53 | 0.18 | 0.66 | 0.05 | |||||

| 5–9 years | 1183 (77.2) | 1003 (65.4) | 758 (49.5) | 20 (1.3) | |||||

| 10–15 years | 2702 (78.0) | 2335 (67.4) | 1737 (50.1) | 73 (2.1) | |||||

| District | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||

| Rubavu | 1659 (91.8) | 1594 (88.2) | 1144 (63.3) | 23 (1.3) | |||||

| Rutsiro | 457 (54.0) | 197 (23.3) | 374 (44.2) | 5 (0.6) | |||||

| Nyamasheke | 649 (60.0) | 521 (48.2) | 308 (28.5) | 28 (2.6) | |||||

| Rusizi | 1120 (88.6) | 1026 (81.2) | 669 (52.9) | 37 (2.9) | |||||

| School | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||

| Rambo | 773 (93.0) | 743 (89.4) | 566 (68.1) | 12 (1.4) | |||||

| Rubona | 886 (90.8) | 851 (87.2) | 578 (59.2) | 11 (1.1) | |||||

| Rusororo | 240 (54.4) | 95 (21.5) | 200 (45.4) | 3 (0.7) | |||||

| Sure | 217 (53.6) | 102 (25.2) | 174 (43.0) | 2 (0.5) | |||||

| Buhokoro | 360 (61.2) | 289 (49.2) | 169 (28.7) | 18 (3.1) | |||||

| Mukoma | 289 (58.6) | 232 (47.1) | 139 (28.2) | 10 (2.0) | |||||

| Bugumira | 421 (87.2) | 387 (80.2) | 249 (51.7) | 10 (2.1) | |||||

| Nkombo | 698 (89.5) | 638 (81.8) | 419 (53.7) | 27 (3.5) | |||||

| Consistency of stool | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.62 | 0.82 | |||||

| Formed | 49 (89.1) | 46 (83.6) | 29 (52.7) | 0 | |||||

| Soft | 3817 (77.6) | 3274 (66.6) | 2457 (50.0) | 93 (1.9) | |||||

| Loose | 6 (100.0) | 6 (100.0) | 2 (33.3) | 0 | |||||

| Watery | 13 (76.5) | 12 (70.6) | 7 (41.2) | 0 | |||||

| Stunting status (HAZ) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.04 | |||||

| Non stunted | 2569 (75.6) | 2203 (64.8) | 1638 (48.2) | 54 (1.6) | |||||

| Stunted | 1316 (82.3) | 1135 (71.0) | 857 (53.6) | 39 (2.4) | |||||

| Wasting status (BAZ) | 0.002 | <0.001 | 0.13 | 0.87 | |||||

| Not wasted | 3672 (78.2) | 3175 (67.6) | 2357 (50.2) | 87 (1.9) | |||||

| wasted | 213 (70.5) | 163 (54.0) | 138 (45.7) | 6 (1.9) | |||||

| Variables | Hookworms | Ascaris lumbricoides | Trichirus trichiura | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β (S.E) | 95% CI | p | β (S.E) | 95% CI | p | β (S.E) | 95% CI | p | ||

| Sex | Male | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Female | 1.14 (0.24) | 0.75–1.73 | 0.51 | 0.92 (0.03) | 0.85–1.00 | 0.06 | 0.94 (0.03) | 0.88–1.00 | 0.08 | |

| Age | 5–9 years | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| 10–15 years | 1.45 (0.37) | 0.87–2.4 | 0.15 | 1.06 (0.04) | 0.97–1.16 | 0.15 | 1.13 (0.04) | 1.05–1.21 | 0.001 | |

| District | Rubavu | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Rutsiro | 0.44 (0.22) | 0.16–1.18 | 0.1 | 0.54 (0.03) | 0.48–0.61 | <0.001 | 0.09 (0.006) | 0.07–0.10 | <0.001 | |

| Nyamasheke | 2.00 (0.56) | 1.15–3.48 | 0.01 | 0.28 (0.018) | 0.25–0.32 | <0.001 | 0.23 (0.115) | 0.21–0.25 | <0.001 | |

| Rusizi | 2.10 (0.57) | 1.23–3.58 | 0.01 | 0.67 (0.033) | 0.61–0.74 | <0.001 | 0.63 (0.025) | 0.59–0.68 | <0.001 | |

| Stunting | Not stunted | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Stunted | 1.30 (0.29) | 0.84–2.01 | 0.23 | 1.17 (0.05) | 1.08–1.28 | <0.001 | 1.10 (0.041) | 1.02–1.19 | 0.006 | |

| Wasting | Not wasted | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Wasted | 1.10 (0.46) | 0.47–2.53 | 0.82 | 1.02 (0.09) | 0.86–1.21 | 0.79 | 0.91 (0.071) | 0.78–1.06 | 0.26 | |

| Variables | Univariate Analysis | Multivariate Analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cOR | 95% CI | p-Value | aOR | 95% CI | p-Value | ||

| Sex | Female | 1 | <0.001 | 1 | 0.012 | ||

| Male | 1.27 | 1.11–1.46 | 1.21 | 1.04–1.40 | |||

| Age categories | 5–9 years | 1 | 0.53 | ||||

| 10–15 years | 1.04 | 0.91–1.21 | |||||

| District | Rutsiro | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Nyamasheke | 1.28 | 1.07–1.53 | 0.008 | 1.23 | 1.02–1.48 | 0.029 | |

| Rusizi | 6.62 | 5.31–8.25 | <0.001 | 5.94 | 4.75–7.44 | <0.001 | |

| Rubavu | 9.54 | 7.69–11.84 | <0.001 | 9.5 | 7.64–11.81 | <0.001 | |

| School | Sure | 1 | |||||

| Rambo | 11.55 | 8.30–16.07 | <0.001 | ||||

| Rubona | 8.53 | 6.37–11.42 | <0.001 | ||||

| Rusororo | 1.03 | 0.79–1.36 | 0.81 | ||||

| Buhokoro | 1.37 | 1.06–1.77 | 0.02 | ||||

| Mukoma | 1.23 | 0.94–1.60 | 0.13 | ||||

| Bugumira | 5.9 | 4.24–8.21 | <0.001 | ||||

| Nkombo | 7.37 | 5.46–9.96 | <0.001 | ||||

| Stunting | Non stunted | 1 | 1 | 0.001 | |||

| Stunted | 1.5 | 1.30–1.75 | <0.001 | 1.34 | 1.13–1.58 | ||

| Wasted | Non wasted | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Wasted | 0.67 | 0.52 -0.86 | 0.002 | 1 | 0.76–1.32 | ||

| Schistosomiasis | No | 1 | 1.48–3.14 | <0.001 | 1 | 0.001 | |

| Yes | 2.16 | 1.95 | 1.31–2.90 | ||||

| Variables | Hookworms | Ascaris lumbricoides | Trichirus trichiura | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate Analysis | Multivariate Analysis | Univariate Analysis | Multivariate Analysis | Univariate Analysis | Multivariate Analysis | ||||||||

| OR (95% CI) | p | OR (95% CI) | p | OR (95% CI) | p | OR (95% CI) | p | OR (95% CI) | p | OR (95% CI) | p | ||

| Sex | Female | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| Male | 0.93 (0.62–1.41) | 0.74 | 1.15 (1.04–1.30) | 0.009 | 1.13 (1.00–1.27) | 0.05 | 1.17 (1.04–1.31) | 0.011 | 1.12 (0.97–1.29) | 0.11 | |||

| Age | 5–9 years | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| 10–15 years | 1.63 (0.99–2.68) | 0.06 | 1.46 (0.88–2.43) | 0.14 | 1.03 (0.91–1.16) | 0.66 | 1.1 (0.96–1.24) | 0.18 | |||||

| District | Rutsiro | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Rubavu | 2.17 (0.82–5.72) | 0.12 | 2.22 (0.84–5.86) | 0.11 | 2.18 (1.84–2.57) | <0.001 | 2.19 (1.85–2.59) | <0.001 | 24.65 (19.90–30.54) | <0.001 | 24.76 (19.96–30.72) | <0.001 | |

| Nyamasheke | 4.47 (1.72–11.63) | 0.002 | 4.50 (1.73–11.70) | 0.002 | 0.50 (0.42–0.61) | <0.001 | 0.50 (0.42–0.61) | <0.001 | 3.06 (2.51–3.74) | <0.001 | 3.08 (2.52–3.76) | <0.001 | |

| Rusizi | 5.07 (1.99–12.96) | 0.001 | 4.72 (1.84–12.13) | 0.001 | 1.42 (1.19–1.69) | <0.001 | 1.35 (1.13–1.62) | 0.001 | 14.20 (11.48–17.57) | <0.001 | 13.57 (10.94–16.83) | <0.001 | |

| School | Sure | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||

| Rambo | 2.95 (0.66–13.25) | 0.16 | 2.84 (2.22–3.62) | <0.001 | 25.08 (18.31–34.36) | <0.001 | |||||||

| Rubona | 2.30 (0.51–10.41) | 0.28 | 1.93 (1.52–2.44) | <0.001 | 20.22 (15.09–27.10) | <0.001 | |||||||

| Rusororo | 1.38 (0.23–8.30) | 0.73 | 1.10 (0.84–1.45) | 0.49 | 0.82 (0.59–1.12) | 0.211 | |||||||

| Buhokoro | 6.36 (1.47–27.58) | 0.01 | 0.54 (0.41–0.70) | <0.001 | 2.87 (2.18–3.79) | <0.001 | |||||||

| Mukoma | 4.17 (0.91–19.15) | 0.07 | 0.52 (0.39–0.69) | <0.001 | 2.64 (1.98–3.51) | <0.001 | |||||||

| Bugumira | 4.25 (0.93–19.51) | 0.06 | 1.42 (1.09–1.85) | 0.01 | 12.01 (8.75–16.48) | <0.001 | |||||||

| Nkombo | 7.23 (1.71–30.54) | 0.01 | 1.54 (1.21–1.96) | <0.001 | 13.35 (10.00–17.82) | <0.001 | |||||||

| Stunting | Non stunted | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Stunted | 1.55 (1.02–2.35) | 0.04 | 1.28 (0.83–1.99) | 0.26 | 1.24 (1.10–1.40) | <0.001 | 1.22 (1.07–1.38) | 0.002 | 1.33 (1.17–1.51) | <0.001 | 1.22 (1.04–1.42) | 0.01 | |

| Wasted | Non wasted | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| wasted | 1.07 (0.47–2.48) | 0.87 | 0.84 (0.66–1.05) | 0.13 | 0.56 (0.44–0.71) | <0.001 | 0.91 (0.69–1.20) | 0.49 | |||||

| Schistosomiasis | No | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Yes | 3.00 (1.65–5.47) | <0.001 | 2.28 (1.24–4.19) | 0.008 | 0.84 (0.66–1.05) | 0.13 | 1.01 (0.79–1.13) | 0.93 | 2.40 (1.74–3.31) | <0.001 | 2.40 (1.74–3.31) | <0.001 | |

| Characteristics | n | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 2344 | 46.9 |

| Female | 2654 | 53.1 | |

| Age (Years) | 5–9 years | 1533 | 30.7 |

| 10–15 years | 3465 | 69.3 | |

| Stunting (HAZ) a | Non stunted | 3399 | 68.0 |

| Stunted | 1599 | 32.0 | |

| Wasting (BAZ) b | Not wasted | 4696 | 94.0 |

| wasted | 302 | 6.0 | |

| District | Rubavu | 1807 | 36.2 |

| Rutsiro | 846 | 16.9 | |

| Nyamasheke | 1081 | 21.6 | |

| Rusizi | 1264 | 25.3 | |

| District | Schools | ||

| Rubavu | Rambo | 831 | 16.6 |

| Rubona | 976 | 19.5 | |

| Rutsiro | Rusororo | 441 | 8.8 |

| Sure | 405 | 8.1 | |

| Nyamasheke | Buhokoro | 588 | 11.8 |

| Mukoma | 493 | 9.9 | |

| Rusizi | Bugumira | 484 | 9.7 |

| Nkombo | 780 | 15.6 | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kabatende, J.; Mugisha, M.; Ntirenganya, L.; Barry, A.; Ruberanziza, E.; Mbonigaba, J.B.; Bergman, U.; Bienvenu, E.; Aklillu, E. Prevalence, Intensity, and Correlates of Soil-Transmitted Helminth Infections among School Children after a Decade of Preventive Chemotherapy in Western Rwanda. Pathogens 2020, 9, 1076. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens9121076

Kabatende J, Mugisha M, Ntirenganya L, Barry A, Ruberanziza E, Mbonigaba JB, Bergman U, Bienvenu E, Aklillu E. Prevalence, Intensity, and Correlates of Soil-Transmitted Helminth Infections among School Children after a Decade of Preventive Chemotherapy in Western Rwanda. Pathogens. 2020; 9(12):1076. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens9121076

Chicago/Turabian StyleKabatende, Joseph, Michael Mugisha, Lazare Ntirenganya, Abbie Barry, Eugene Ruberanziza, Jean Bosco Mbonigaba, Ulf Bergman, Emile Bienvenu, and Eleni Aklillu. 2020. "Prevalence, Intensity, and Correlates of Soil-Transmitted Helminth Infections among School Children after a Decade of Preventive Chemotherapy in Western Rwanda" Pathogens 9, no. 12: 1076. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens9121076

APA StyleKabatende, J., Mugisha, M., Ntirenganya, L., Barry, A., Ruberanziza, E., Mbonigaba, J. B., Bergman, U., Bienvenu, E., & Aklillu, E. (2020). Prevalence, Intensity, and Correlates of Soil-Transmitted Helminth Infections among School Children after a Decade of Preventive Chemotherapy in Western Rwanda. Pathogens, 9(12), 1076. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens9121076