Host Pathogen Relations: Exploring Animal Models for Fungal Pathogens

Abstract

:1. Introduction

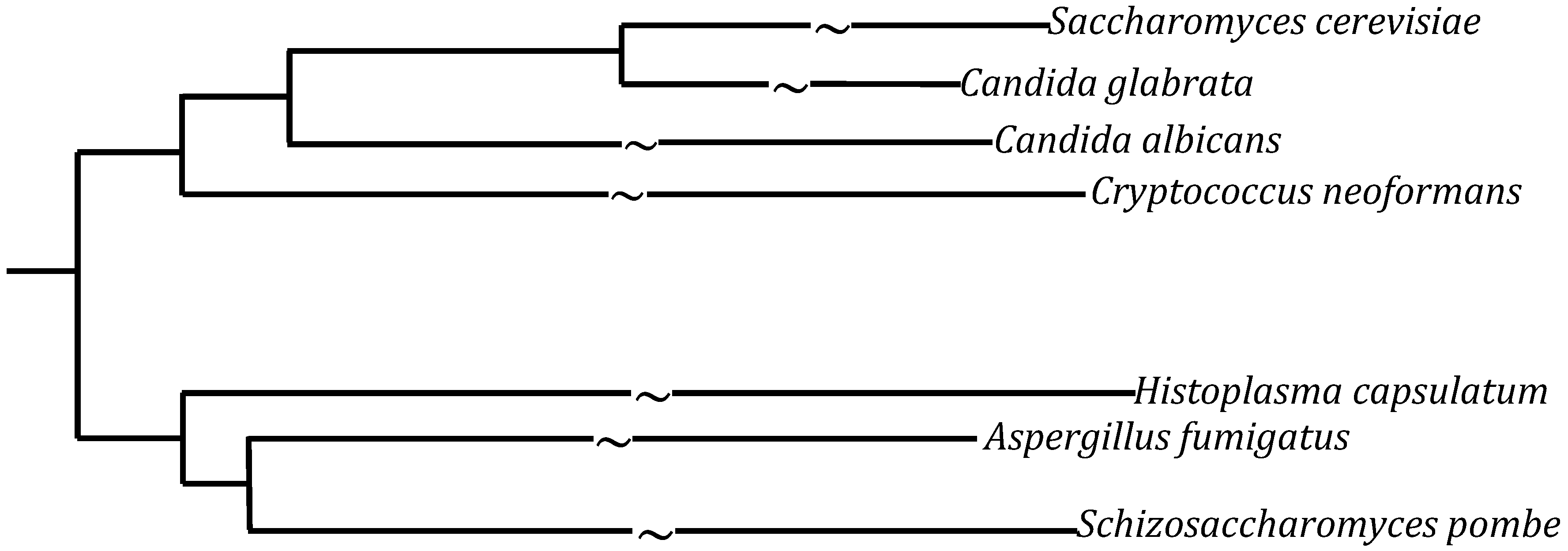

1.1. Candida

1.2. Cryptococcus

1.3. Histoplasma

1.4. Aspergillus

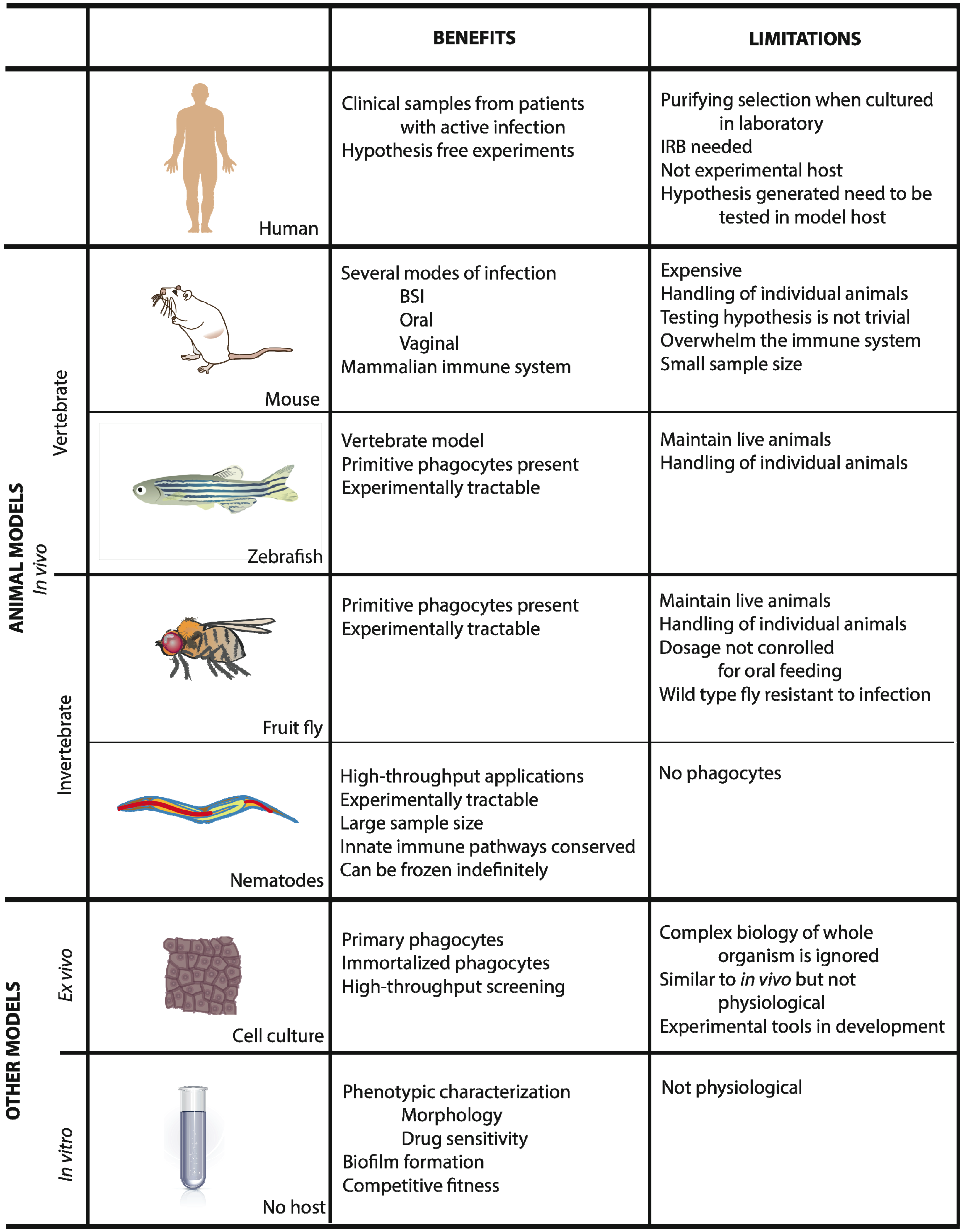

2. Animal Models

2.1. Mus Musculus

2.2. Zebrafish

2.3. Drosophila Melanogaster

2.4. Caenorhabditis Elegans

3. Ex Vivo Systems

4. In Vitro Systems

5. Conclusions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Fungal Disease. Available online: http://www.cdc.gov/fungal/ (accessed on 27 January 2014).

- Pfaller, M.A.; Diekema, D.J. Epidemiology of invasive candidiasis: A persistent public health problem. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2007, 20, 133–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birren, B.G.F.E.L. Fungal Genome Initiative: A White Paper for Fungal Comparative Genomics; Fungal Genome Initiative Steering Committee: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Centres for Disease Control and Prevention. Fluconazole-Resistant Candida. In Antibiotic Resistance Threats in the United States; Disease Control and Prevention: Atlanta, GA, United States, 2013; p. 63. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Candidiasis. Available online: http://www.cdc.gov/fungal/diseases/candidiasis/ (accessed on 27 January 2014).

- Fidel, P.L.; Vazquez, J.A.; Sobel, J.D. Candida glabrata: Review of epidemiology, pathogenesis, and clinical disease with comparison to C. albicans. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 1999, 12, 80–96. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. C. neoformans cryptococcosis. Available online: http://www.cdc.gov/fungal/diseases/cryptococcosis-neoformans/ (accessed on 27 January 2014).

- Price, M.S.; Betancourt-Quiroz, M.; Price, J.L.; Toffaletti, D.L.; Vora, H.; Hu, G.; Kronstad, J.W.; Perfect, J.R. Cryptococcus neoformans requires a functional glycolytic pathway for disease but not persistence in the host. MBio 2011, 2, e00103-11. [Google Scholar]

- Fraser, J.A.; Giles, S.S.; Wenink, E.C.; Geunes-Boyer, S.G.; Wright, J.R.; Diezmann, S.; Allen, A.; Stajich, J.E.; Dietrich, F.S.; Perfect, J.R.; et al. Same-sex mating and the origin of the Vancouver Island Cryptococcus gattii outbreak. Nature 2005, 437, 1360–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rappleye, C.A.; Engle, J.T.; Goldman, W.E. RNA interference in Histoplasma capsulatum demonstrates a role for α-(1,3)-glucan in virulence. Mol. Microbiol. 2004, 53, 153–165. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Histoplasmosis. Available online: http://www.cdc.gov/fungal/diseases/histoplasmosis/ (accessed on 27 January 2014).

- Willger, S.D.; Puttikamonkul, S.; Kim, K.-H.; Burritt, J.B.; Grahl, N.; Metzler, L.J.; Barbuch, R.; Bard, M.; Lawrence, C.B.; Cramer, R.A., Jr. A sterol-regulatory element binding protein is required for cell polarity, hypoxia adaptation, azole drug resistance, and virulence in Aspergillus fumigatus. PLoS Pathog. 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedayati, M.T.; Pasqualotto, A.C.; Warn, P.A.; Bowyer, P.; Denning, D.W. Aspergillus flavus: Human pathogen, allergen and mycotoxin producer. Microbiology 2007, 153, 1677–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conti, H.R.; Shen, F.; Nayyar, N.; Stocum, E.; Sun, J.N.; Lindemann, M.J.; Ho, A.W.; Hai1, J.H.; Yu, J.J.; Jung, J.W.; et al. Th17 cells and IL-17 receptor signaling are essential for mucosal host defense against oral candidiasis. J. Exp. Med. 2009, 206, 299–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fidel, P.L.; Cutright, J.L.; Tait, L.; Sobel, J.D. A murine model of Candida glabrata vaginitis. J. Infect. Dis. 1996, 173, 425–431. [Google Scholar]

- Takakura, N.; Sato, Y.; Ishibashi, H.; Oshima, H.; Uchida, K.; Yamaguchi, H.; Abe, S. A novel murine model of oral candidiasis with local symptoms characteristic of oral thrush. Microbiol. Immunol. 2003, 47, 321–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fidel, P.L., Jr. Distinct protective host defenses against oral and vaginal candidiasis. Med. Mycol. 2002, 40, 359–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, A.Y.; Köhler, J.; Coggshall, K.T.; Rooijen, N.V.; Pier, G.B. Mucosal damage and neutropenia are required for Candida albicans dissemination. PLoS Pathog. 2008, 4, e35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumamoto, C.A.; Vinces, M.D. Alternative Candida albicans lifestyles: Growth on surfaces. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2005, 59, 113–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thewes, S.; Kretschmar, M.; Park, H.; Schaller, M.; Filler, S.G.; Hube, B. In vivo and ex vivo comparative transcriptional profiling of invasive and non-invasive Candida albicans isolates identifies genes associated with tissue invasion. Mol. Microbiol. 2007, 63, 1606–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wormley, F.L., Jr.; Steele, C.; Wozniak, K.; Fujihashi, K.; McGhee, J.R.; Fidel, P.L., Jr. Resistance of T-Cell Receptor δ-Chain-Deficient Mice to Experimental Candidaalbicans Vaginitis. Infect. Immun. 2001, 69, 7162–7164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeda, F.; Wakai, Y.; Matsumoto, S.; Maki, K.; Watabe, E.; Tawara, S.; Goto, T.; Watanabe, Y.; Matsumoto, F.; Kuwahara, S. Efficacy of FK463, a new lipopeptide antifungal agent, in mouse models of disseminated candidiasis and aspergillosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2000, 44, 614–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Berestein, G.; Hopfer, R.L.; Mehta, R.; Mehta, K.; Hersh, E.M.; Juliano, R.L. Liposome-encapsulated amphotericin B for treatment of disseminated candidiasis in neutropenic mice. J. Infect. Dis. 1984, 150, 278–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Sar, A.M.; Appelmelk, B.J.; Vandenbroucke-Grauls, C.M.J.E.; Bitter, W. A star with stripes: Zebrafish as an infection model. Trends Microbiol. 2004, 12, 451–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobin, D.M.; May, R.C.; Wheeler, R.T. Zebrafish: A see-through host and a fluorescent toolbox to probe host–pathogen interaction. PLoS Pathog. 2012, 8, e1002349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, H.-J.; Köhler, J.R.; DiDomenico, B.; Loebenberg, D.; Cacciapuoti, A.; Fink, G.R. Nonfilamentous C. albicans mutants are avirulent. Cell 1997, 90, 939–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Kohler, J.; Fink, G.R. Suppression of hyphal formation in Candida albicans by mutation of a STE12 homolog. Science 1994, 266, 1723–1726. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz, M.C.; Bender, J.A.; Fink, G.R. Transcriptional response of Candida albicans upon internalization by macrophages. Eukaryot. Cell 2004, 3, 1076–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, C.; Pastor, K.; Gonzalez, A.Y.; Lorenz, M.C.; Rao, R.P. The role of Candida albicans AP-1 protein against host derived ROS in in vivo models of infection. Virulence 2013, 4, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, C.; Yun, M.; Politz, S.M.; Rao, R.P. A pathogenesis assay using Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Caenorhabditis elegans reveals novel roles for yeast AP-1, Yap1, and host dual oxidase BLI-3 in fungal pathogenesis. Eukaryot. Cell 2009, 8, 1218–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Németh, T.; Tóth, A.; Szenzenstein, J.; Horváth, P.; Nosanchuk, J.D.; Grózer, Z.; Tóth, R.; Papp, C.; Hamari, Z.; Vágvölgyi, C.; Gácser, A. Characterization of Virulence Properties in the C. parapsilosis Sensu Lato Species. PLoS One 2013, 8, e68704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robbins, S.L.; Kumar, V.; Cotran, R.S. Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease, 8th ed.; Saunders/Elsevier: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2010; Volume xiv, p. 1450. [Google Scholar]

- Brothers, K.M.; Newman, Z.R.; Wheeler, R.T. Live imaging of disseminated candidiasis in zebrafish reveals role of phagocyte oxidase in limiting filamentous growth. Eukaryot. Cell 2011, 10, 932–944. [Google Scholar]

- Summerton, J.; Weller, D. Morpholino antisense oligomers: Design, preparation, and properties. Antisense Nucleic Acid Drug Dev. 1997, 7, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, B.R.; Johnson, A.D. Control of filament formation in Candida albicans by the transcriptional repressor TUP1. Science 1997, 277, 105–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, R.P.; Hunter, A.; Kashpur, O.; Normanly, J. Aberrant synthesis of indole-3-acetic acid in Saccharomyces cerevisiae triggers morphogenic transition, a virulence trait of pathogenic fungi. Genetics 2010, 185, 211–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumamoto, C.A.; Vinces, M.D. Contributions of hyphae and hypha-co-regulated genes to Candida albicans virulence. Cell. Microbiol. 2005, 7, 1546–1554. [Google Scholar]

- Brennan, M.; Thomas, D.Y.; Whiteway, M.; Kavanagh, K. Correlation between virulence of Candida albicans mutants in mice and Galleria mellonella larvae. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 2002, 34, 153–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamilos, G.; Lionakis, M.S.; Lewis, R.E.; Lopez-Ribot, J.L.; Saville, S.P.; Albert, N.D.; Halder, G.; Kontoyiannis, D.P. Drosophila melanogaster as a facile model for large-scale studies of virulence mechanisms and antifungal drug efficacy in Candida species. J. Infect. Dis. 2006, 193, 1014–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pukkila-Worley, R.; Ausubel, F.M.; Mylonakis, E. Candida albicans infection of Caenorhabditis elegans induces antifungal immune defenses. PLoS Pathog. 2011, 7, e1002074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frohner, I.E.; Bourgeois, C.; Yatsyk, K.; Majer, O.; Kuchler, K. Candida albicans cell surface superoxide dismutases degrade host-derived reactive oxygen species to escape innate immune surveillance. Mol. Microbiol. 2009, 71, 240–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chávez, V.; Mohri-Shiomi, A.; Maadani, A.; Vega, L.A.; Garsin, D.A. Oxidative stress enzymes are required for DAF-16-mediated immunity due to generation of reactive oxygen species by Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 2007, 176, 1567–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kornberg, T.B.; Krasnow, M.A. The Drosophila genome sequence: Implications for biology and medicine. Science 2000, 287, 2218–2220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leclerc, V.; Reichhart, J.M. The immune response of Drosophila melanogaster. Immunol. Rev. 2004, 198, 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alarco, A.-M.; Marcil, A.; Chen, J.; Suter, B.; Thomas, D.; Whiteway, M. Immune-deficient Drosophila melanogaster: A model for the innate immune response to human fungal pathogens. J. Immunol. 2004, 172, 5622–5628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glittenberg, M.T.; Kounatidis, I.; Christensen, D.; Kostov, M.; Kimber, S.; Roberts, I.; Ligoxygakis, P. Pathogen and host factors are needed to provoke a systemic host response to gastrointestinal infection of Drosophila larvae by Candida albicans. Dis. Models Mech. 2011, 4, 515–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemaitre, B.; Nicolas, E.; Michaut, L.; Reichhart, J.M.; Hoffmann, J.A. The Dorsoventral Regulatory Gene Cassette spätzle/Toll/cactus Controls the Potent Antifungal Response in Drosophila Adults. Cell 1996, 86, 973–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintin, J.; Asmar, J.; Matskevich, A.A.; Lafarge, M.C.; Ferrandon, D. The Drosophila Toll pathway controls but does not clear Candida glabrata infections. J. Immunol. 2013, 190, 2818–2827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiernagle, T. Maintenance of C. elegans. WormBook. The C. elegans Research Community; WormBook: Minneapolis, United States, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ewbank, J.J. Tackling both sides of the host–pathogen equation with Caenorhabditis elegans. Microbes Infect. 2002, 4, 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garsin, D.A.; Villanueva, J.M.; Begun, J.; Kim, D.H.; Sifri, C.D.; Calderwood, S.B.; Ruvkun, G.; Ausubel, F.M. Long-lived C. elegans daf-2 mutants are resistant to bacterial pathogens. Science 2003, 300, 1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgkin, J.; Kuwabara, P.E.; Corneliussen, B. A novel bacterial pathogen, Microbacterium nematophilum, induces morphological change in the nematode C. elegans. Curr. Biol. 2000, 10, 1615–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mylonakis, E.; Ausubel, F.M.; Perfect, J.R.; Heitman, J.; Calderwood, S.B. Killing of Caenorhabditis elegans by Cryptococcus neoformans as a model of yeast pathogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 15675–15680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahajan-Miklos, S.; Tan, M.-W.; Rahme, L.G.; Ausube, F.M. Molecular Mechanisms of Bacterial Virulence Elucidated Using a Pseudomonas aeruginosa–Caenorhabditis elegans Pathogenesis Model. Cell 1999, 96, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mylonakis, E.; Idnurm, A.; Moreno, R.; Khoury, J.E.; Rottman, J.B.; Ausubel, F.M.; Heitman, J.; Calderwood, S.B. Cryptococcus neoformans Kin1 protein kinase homologue, identified through a Caenorhabditis elegans screen, promotes virulence in mammals. Mol. Microbiol. 2004, 54, 407–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D'Souza, C.A.; Alspaugh, J.A.; Yue, C.; Harashima, T.; Cox, G.M.; Perfect, J.R.; Heitman, J. Cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase controls virulence of the fungal pathogen Cryptococcus neoformans. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2001, 21, 3179–3191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.H.; Rossi, J.J. RNAi mechanisms and applications. Biotechniques 2008, 44, 613. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin-Bejerano, I.; Fraser, I.; Grisafi, P.; Fink, G.R. Phagocytosis by neutrophils induces an amino acid deprivation response in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Candida albicans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 11007–11012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, R.T.; Fink, G.R. A drug-sensitive genetic network masks fungi from the immune system. PLoS Pathog. 2006, 2, e35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenz, M.C.; Fink, G.R. The glyoxylate cycle is required for fungal virulence. Nature 2001, 412, 83–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harriott, M.M.; Lilly, E.A.; Rodriguez, T.E.; Fidel, P.L., Jr.; Noverr, M.C. Candida albicans forms biofilms on the vaginal mucosa. Microbiology 2010, 156, 3635–3644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazly, A.; Jainb, C.; Dehnera, A.C.; Issib, L.; Lillyc, E.A.; Alid, A.; Caod, H.; Fidel, P.L., Jr.; Raob, R.P.; Kaufman, P.D. Chemical screening identifies filastatin, a small molecule inhibitor of Candida albicans adhesion, morphogenesis, and pathogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 13594–13599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homann, O.R.; Dea, J.; Noble, S.M.; Johnson, A.D. A phenotypic profile of the Candida albicans regulatory network. PLoS Genet. 2009, 5, e1000783. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, P.-C.; Yang, C.-Y.; Lan, C.-Y. Candida albicans Hap43 is a repressor induced under low-iron conditions and is essential for iron-responsive transcriptional regulation and virulence. Eukaryot. Cell 2011, 10, 207–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, Y.-U.; Li, M.; Davis, D.A. Candida albicans ferric reductases are differentially regulated in response to distinct forms of iron limitation by the Rim101 and CBF transcription factors. Eukaryot. Cell 2008, 7, 1168–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Toole, G.; Kaplan, H.B.; Kolter, R. Biofilm formation as microbial development. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2000, 54, 49–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogan, D.A.; Vik, Å.; Kolter, R. A Pseudomonas aeruginosa quorum-sensing molecule influences Candida albicans morphology. Mol. Microbiol. 2004, 54, 1212–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, J.; Kuhn, D.M.; Mukherjee, P.K.; Hoyer, L.L.; McCormick, T.; Ghannoum, M.A. Biofilm formation by the fungal pathogen Candida albicans: Development, architecture, and drug resistance. J. Bacteriol. 2001, 183, 5385–5394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaller, M.; Bein, M.; Korting, H.C.; Baur, S.; Hamm, G.; Monod, M.; Beinhauer, S.; Hube, B. The secreted aspartyl proteinases Sap1 and Sap2 cause tissue damage in an in vitro model of vaginal candidiasis based on reconstituted human vaginal epithelium. Infect. Immun. 2003, 71, 3227–3234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2014 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Harwood, C.G.; Rao, R.P. Host Pathogen Relations: Exploring Animal Models for Fungal Pathogens. Pathogens 2014, 3, 549-562. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens3030549

Harwood CG, Rao RP. Host Pathogen Relations: Exploring Animal Models for Fungal Pathogens. Pathogens. 2014; 3(3):549-562. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens3030549

Chicago/Turabian StyleHarwood, Catherine G., and Reeta P. Rao. 2014. "Host Pathogen Relations: Exploring Animal Models for Fungal Pathogens" Pathogens 3, no. 3: 549-562. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens3030549

APA StyleHarwood, C. G., & Rao, R. P. (2014). Host Pathogen Relations: Exploring Animal Models for Fungal Pathogens. Pathogens, 3(3), 549-562. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens3030549