Enterovirus-D68—Neglected Pathogen in Acute Respiratory Infections: Insights from Croatia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection

2.2. Detection of Enteroviruses

2.3. Detection of EV-D68 by Real-Time RT PCR

2.4. Sequencing and Bioinformatic Analysis

2.5. Phylogenetic Analysis

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

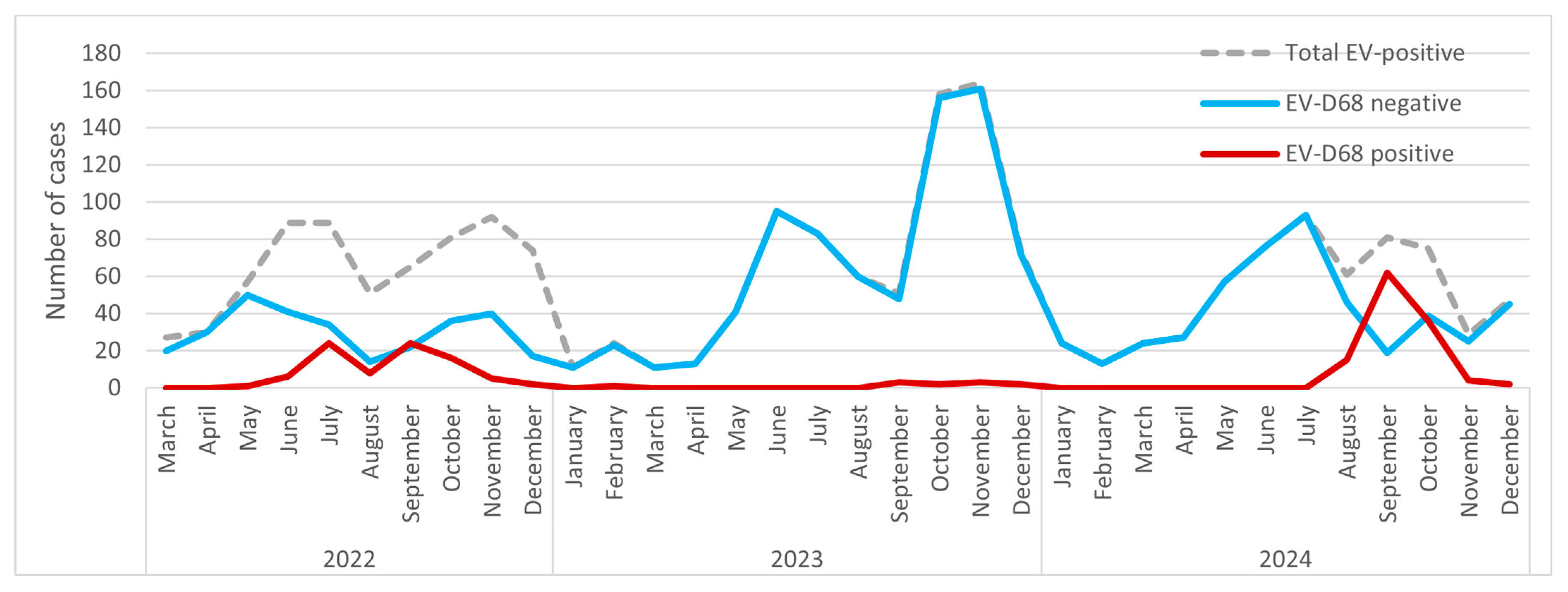

3.1. Annual and Monthly Fluctuations in EV and EV-D68 Infections

3.2. Demographic Characteristics of EV and EV-D68–Positive Cases

3.3. Primary Diagnosis of Enterovirus-Positive Patients

3.4. Viral Coinfections

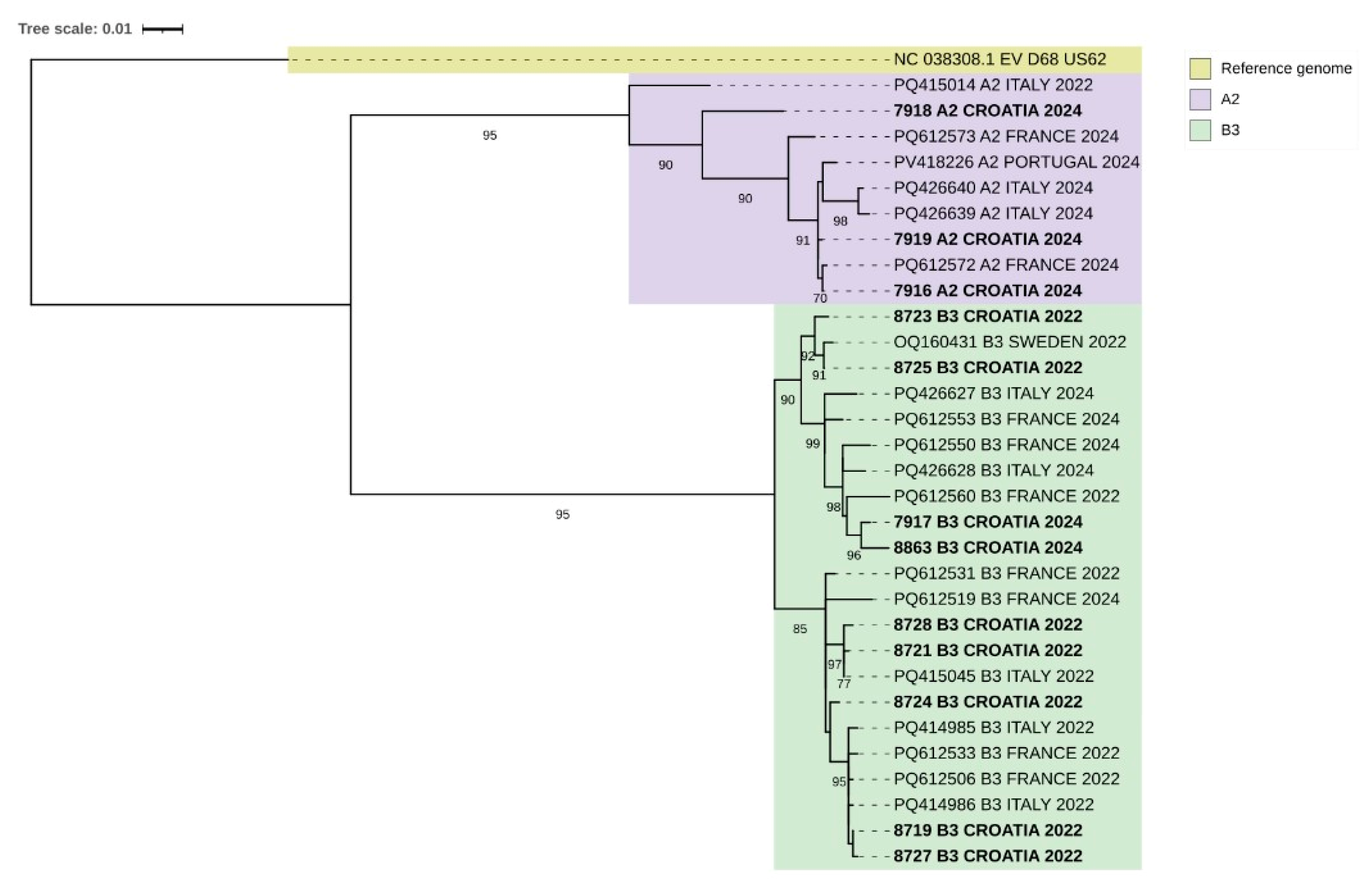

3.5. EV-D68 Sequences—Phylogenetic Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Foster, C.B.; Friedman, N.; Carl, J.; Piedimonte, G. Enterovirus D68: A Clinically Important Respiratory Enterovirus. Cleve. Clin. J. Med. 2015, 82, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schieble, J.H.; Fox, V.L.; Lennette, E.H. A Probable New Human Picornavirus Associated with Respiratory Diseases. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1967, 85, 297–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khetsuriani, N.; Lamonte-Fowlkes, A.; Oberst, S.; Pallansch, M.A. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Enterovirus Surveillance—United States, 1970–2005. MMWR Surveill. Summ. 2006, 55, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Tokarz, R.; Firth, C.; Madhi, S.A.; Howie, S.R.C.; Wu, W.; Sall, A.A.; Haq, S.; Briese, T.; Lipkin, W.I. Worldwide Emergence of Multiple Clades of Enterovirus 68. J. Gen. Virol. 2012, 93, 1952–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holm-Hansen, C.C.; Midgley, S.E.; Fischer, T.K. Global Emergence of Enterovirus D68: A Systematic Review. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2016, 16, e64–e75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Clusters of Acute Respiratory Illness Associated with Human Enterovirus 68--Asia, Europe, and United States, 2008–2010. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2011, 60, 1301–1304. [Google Scholar]

- Midgley, C.M.; Jackson, M.A.; Selvarangan, R.; Turabelidze, G.; Obringer, E.; Johnson, D.; Giles, B.L.; Patel, A.; Echols, F.; Oberste, M.S.; et al. Severe Respiratory Illness Associated with Enterovirus D68—Missouri and Illinois, 2014. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2014, 63, 798–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oermann, C.M.; Schuster, J.E.; Conners, G.P.; Newland, J.G.; Selvarangan, R.; Jackson, M.A. Enterovirus D68. A Focused Review and Clinical Highlights from the 2014 U.S. Outbreak. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2015, 12, 775–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imamura, T.; Oshitani, H. Global Reemergence of Enterovirus D68 as an Important Pathogen for Acute Respiratory Infections. Rev. Med. Virol. 2015, 25, 102–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijer, A.; Benschop, K.S.; Donker, G.A.; Avoort, H.G. van der Continued Seasonal Circulation of Enterovirus D68 in the Netherlands, 2011–2014. Eurosurveillance 2014, 19, 20935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, S.; Bosis, S.; Niesters, H.; Principi, N. Enterovirus D68 Infection. Viruses 2015, 7, 6043–6050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, J.S.; Mirch, M.C.; Amin, P.M. Enterovirus D68: What Pediatric Healthcare Professionals Need to Know. J. Spec. Pediatr. Nurs. 2015, 20, 131–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meijer, A.; van der Sanden, S.; Snijders, B.E.P.; Jaramillo-Gutierrez, G.; Bont, L.; van der Ent, C.K.; Overduin, P.; Jenny, S.L.; Jusic, E.; van der Avoort, H.G.A.M.; et al. Emergence and Epidemic Occurrence of Enterovirus 68 Respiratory Infections in The Netherlands in 2010. Virology 2012, 423, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greninger, A.L.; Naccache, S.N.; Messacar, K.; Clayton, A.; Yu, G.; Somasekar, S.; Federman, S.; Stryke, D.; Anderson, C.; Yagi, S.; et al. A Novel Outbreak Enterovirus D68 Strain Associated with Acute Flaccid Myelitis Cases in the USA (2012–14): A Retrospective Cohort Study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2015, 15, 671–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poelman, R.; Schölvinck, E.H.; Borger, R.; Niesters, H.G.M.; van Leer-Buter, C. The Emergence of Enterovirus D68 in a Dutch University Medical Center and the Necessity for Routinely Screening for Respiratory Viruses. J. Clin. Virol. 2015, 62, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ljubin-Sternak, S.; Vilibić-Cavlek, T.; Kaić, B.; Aleraj, B.; Soprek, S.; Sviben, M.; Mlinarić-Galinović, G. Virologic and epidemiological characteristics of non-polio infection in Croatia over a ten-year period (2000–2009). Acta. Med. Croat. 2011, 65, 237–242. [Google Scholar]

- Majumdar, M.; Celma, C.; Pegg, E.; Polra, K.; Dunning, J.; Martin, J. Detection and Typing of Human Enteroviruses from Clinical Samples by Entire-Capsid Next Generation Sequencing. Viruses 2021, 13, 641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babraham Bioinformatics—FastQC A Quality Control Tool for High Throughput Sequence Data. Available online: https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/ (accessed on 10 September 2024).

- Chen, S. Ultrafast One-Pass FASTQ Data Preprocessing, Quality Control, and Deduplication Using Fastp. Imeta 2023, 2, e107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danecek, P.; Bonfield, J.K.; Liddle, J.; Marshall, J.; Ohan, V.; Pollard, M.O.; Whitwham, A.; Keane, T.; McCarthy, S.A.; Davies, R.M.; et al. Twelve Years of SAMtools and BCFtools. GigaScience 2021, 10, giab008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroneman, A.; Vennema, H.; Deforche, K.; v d Avoort, H.; Peñaranda, S.; Oberste, M.S.; Vinjé, J.; Koopmans, M. An Automated Genotyping Tool for Enteroviruses and Noroviruses. J. Clin. Virol. 2011, 51, 121–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katoh, K.; Standley, D.M. MAFFT Multiple Sequence Alignment Software Version 7: Improvements in Performance and Usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013, 30, 772–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, L.-T.; Schmidt, H.A.; von Haeseler, A.; Minh, B.Q. IQ-TREE: A Fast and Effective Stochastic Algorithm for Estimating Maximum-Likelihood Phylogenies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2015, 32, 268–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letunic, I.; Bork, P. Interactive Tree of Life (iTOL) v6: Recent Updates to the Phylogenetic Tree Display and Annotation Tool. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, W78–W82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benschop, K.S.; Albert, J.; Anton, A.; Andrés, C.; Aranzamendi, M.; Armannsdóttir, B.; Bailly, J.-L.; Baldanti, F.; Baldvinsdóttir, G.E.; Beard, S.; et al. Re-Emergence of Enterovirus D68 in Europe after Easing the COVID-19 Lockdown, September 2021. Eurosurveillance 2021, 26, 2100998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, K.; Winn, A.; Moline, H.; Scobie, H.; Midgley, C.; Kirking, H.; Adjemian, J.; Hartnett, K.; Johns, D.; Jones, J.; et al. Increase in Acute Respiratory Illnesses Among Children and Adolescents Associated with Rhinoviruses and Enteroviruses, Including Enterovirus D68—United States, July–September 2022. MMWR. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2022, 71, 1265–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simoes, M.P.; Hodcroft, E.B.; Simmonds, P.; Albert, J.; Alidjinou, E.K.; Ambert-Balay, K.; Andrés, C.; Antón, A.; Auvray, C.; Bailly, J.-L.; et al. Epidemiological and Clinical Insights into the Enterovirus D68 Upsurge in Europe 2021-2022 and Emergence of Novel B3-Derived Lineages, ENPEN Multicentre Study. J. Infect. Dis. 2024, 230, e917–e928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bubba, L.; Broberg, E.K.; Jasir, A.; Simmonds, P.; Harvala, H. Enterovirus study collaborators Circulation of Non-Polio Enteroviruses in 24 EU and EEA Countries between 2015 and 2017: A Retrospective Surveillance Study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, 350–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harvala, H.; Jasir, A.; Penttinen, P.; Pastore Celentano, L.; Greco, D.; Broberg, E. Surveillance and Laboratory Detection for Non-Polio Enteroviruses in the European Union/European Economic Area, 2016. Euro. Surveill. 2017, 22, 16–00807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sentinel Surveillance. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/seasonal-influenza/surveillance-and-disease-data/facts-sentinel-surveillance (accessed on 30 December 2023).

- Skowronski, D.M.; Chambers, C.; Sabaiduc, S.; Murti, M.; Gustafson, R.; Pollock, S.; Hoyano, D.; Rempel, S.; Allison, S.; De Serres, G.; et al. Systematic Community- and Hospital-Based Surveillance for Enterovirus-D68 in Three Canadian Provinces, August to December 2014. Euro. Surveill. 2015, 20, 30047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiche, J.; Böttcher, S.; Diedrich, S.; Buchholz, U.; Buda, S.; Haas, W.; Schweiger, B.; Wolff, T. Low-Level Circulation of Enterovirus D68–Associated Acute Respiratory Infections, Germany, 2014. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2015, 21, 837–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grizer, C.S.; Messacar, K.; Mattapallil, J.J. Enterovirus-D68—A Reemerging Non-Polio Enterovirus That Causes Severe Respiratory and Neurological Disease in Children. Front. Virol. 2024, 4, 1328457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fall, A.; Han, L.; Abdullah, O.; Norton, J.M.; Eldesouki, R.E.; Forman, M.; Morris, C.P.; Klein, E.; Mostafa, H.H. An Increase in Enterovirus D68 Circulation and Viral Evolution during a Period of Increased Influenza like Illness, The Johns Hopkins Health System, USA, 2022. J. Clin. Virol. 2023, 160, 105379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliabadi, N.; Messacar, K.; Pastula, D.M.; Robinson, C.C.; Leshem, E.; Sejvar, J.J.; Nix, W.A.; Oberste, M.S.; Feikin, D.R.; Dominguez, S.R. Enterovirus D68 Infection in Children with Acute Flaccid Myelitis, Colorado, USA, 2014. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2016, 22, 1387–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helfferich, J.; Calvo, C.; Alpeter, E.; Andrés, C.; Antón, A.; Aubart, M.; Bova, S.M.; Cabrerizo, M.; von Eije, K.; Fabiola, S.; et al. Acute Flaccid Myelitis in Europe between 2016 and 2023: Indicating the Need for Better Registration. Eurosurveillance 2025, 30, 2400579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fall, A.; Abdullah, O.; Han, L.; Norton, J.M.; Gallagher, N.; Forman, M.; Morris, C.P.; Klein, E.; Mostafa, H.H. Enterovirus D68: Genomic and Clinical Comparison of 2 Seasons of Increased Viral Circulation and Discrepant Incidence of Acute Flaccid Myelitis—Maryland, USA. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2024, 11, ofae656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leser, J.S.; Frost, J.L.; Wilson, C.J.; Rudy, M.J.; Clarke, P.; Tyler, K.L. VP1 Is the Primary Determinant of Neuropathogenesis in a Mouse Model of Enterovirus D68 Acute Flaccid Myelitis. J. Virol. 2024, 98, e00397-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrés, C.; Vila, J.; Creus-Costa, A.; Piñana, M.; González-Sánchez, A.; Esperalba, J.; Codina, M.G.; Castillo, C.; Martín, M.C.; Fuentes, F.; et al. Enterovirus D68 in Hospitalized Children, Barcelona, Spain, 2014–2021. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2022, 28, 1327–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodcroft, E.B.; Dyrdak, R.; Andrés, C.; Egli, A.; Reist, J.; de Artola, D.G.M.; Alcoba-Flórez, J.; Niesters, H.G.M.; Antón, A.; Poelman, R.; et al. Evolution, Geographic Spreading, and Demographic Distribution of Enterovirus D68. PLoS Pathog. 2022, 18, e1010515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kujawski, S.A.; Midgley, C.M.; Rha, B.; Lively, J.Y.; Nix, W.A.; Curns, A.T.; Payne, D.C.; Englund, J.A.; Boom, J.A.; Williams, J.V.; et al. Enterovirus D68–Associated Acute Respiratory Illness—New Vaccine Surveillance Network, United States, July–October, 2017 and 2018. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2019, 68, 277–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirvonen, A.; Johannesen, C.K.; Simmonds, P.; Fischer, T.K.; Harvala, H.; Benschop, K.S.M.; Prochazka, B.; Reynders, M.; Bloemen, M.; Ranst, M.V.; et al. Sustained Circulation of Enterovirus D68 in Europe in 2023 and the Continued Evolution of Enterovirus D68 B3-Lineages Associated with Distinct Amino Acid Substitutions in VP1 Protein. J. Clin. Virol. 2025, 178, 105785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Primer/Probe | Sequences (5′→3′) |

|---|---|

| EV-D68 Forward | TGTTCCCACGGTTGAAAACAA |

| EV-D68 Reverse | TGTCTAGCGTCTCATGGTTTTCAC |

| EV-D68 Probe 1 | FAM-TCCGCTATAGTACTTCG-BHQ1 |

| EV-D68 Probe 2 | FAM-ACCGCTATAGTACTTCG-BHQ1 |

| Total Number of EV-Positive Samples | EV-D68 Negative | EV-D68 Positive | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| By year | ||||

| 2022 | 656 (10.0%) | 570 (86.9%) | 86 (13.1%) | |

| 2023 | 785 (8.06%) | 774 (98.6%) | 11 (1.4%) | <0.001 |

| 2024 | 607 (7.35%) | 488 (80.4%) | 119 (19.6) | |

| Demographic characteristics | ||||

| Female | 0.75 | |||

| 2022 | 270 | 126 (78.8%) | 34 (21.2%) | |

| 2023 | 361 | 357 (98.9%) | 4 (1.1%) | |

| 2024 | 226 | 176 (77.9%) | 50 (22.1) | |

| Male | ||||

| 2022 | 386 | 178 (77.4%) | 52 (22.6%) | |

| 2023 | 424 | 417 (98.4%) | 7 (1.6%) | |

| 2024 | 381 | 312 (81.9%) | 69 (18.1%) | |

| Median (months) IQR | ||||

| 2022 | 28 (17–50) | 26 (16–51.75) | 32.5 (16–60.25) | 0.50 |

| 2023 | 30 (18–54) | 30 (18–54) | 30 (18–150) | |

| 2024 | 30 (18–54) | 30 (18–54) | 30 (18–54) | |

| Age groups (%) | ||||

| 0–3 months | 101 (4.9) | 91 (4.9) | 10 (4.6) | 0.019 |

| 4–12 months | 177 (8.7) | 144 (7.9) | 33 (15.3) | |

| 13–24 months | 528 (25.8) | 478 (26.1) | 50 (23.2) | |

| 2–5 years | 972 (47.4) | 876 (47.8) | 96 (44.4) | |

| 6–15 years | 213 (10.4) | 192 (10.5) | 21 (9.7) | |

| >16 years | 58 (2.8) | 52 (2.8) | 6 (2.8) | |

| Primary Diagnosis | EV-Positive (%) | EV-D68 Positive (%) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2022 | |||

| Febrile illness | 420 (64.0) | 54 (62.8) | |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 120 (18.3) | 17 (19.8) | |

| Lower respiratory tract infection | 63 (9.6) | 13 (15.1) | |

| Gastroenteritis | 19 (2.9) | 1 (1.2) | 0.268 |

| Enterovirus infection | 18 (2.7) | 1 (1.2) | |

| Rash | 11 (1.7) | 0 (0) | |

| Meningitis | 5 (0.8) | 0 (0) | |

| 2023 | |||

| Febrile illness | 441 (56.2) | 6 (54.5) | |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 177 (22.5) | 2 (18.2) | |

| Lower respiratory tract infection | 22 (2.8) | 2 (18.2) | |

| Gastroenteritis | 29 (3.7) | 0 (0) | 0.071 |

| Enterovirus infection | 68 (8.7) | 0 (0) | |

| Rash | 35 (4.5) | 1 (9.1) | |

| Meningitis | 13 (1.7) | 0 (0) | |

| 2024 | |||

| Febrile illness | 367 (60.5) | 60 (50.4) | |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 111 (18.3) | 25 (21.0) | |

| Lower respiratory tract infection | 44 (7.2) | 27 (22.7) | |

| Gastroenteritis | 24 (4.0) | 4 (3.4) | <0.001 |

| Enterovirus infection | 31 (5.1) | 1 (0.8) | |

| Rash | 24 (4.0) | 1 (0.8) | |

| Meningitis | 6 (1.0) | 1 (0.8) |

| Year | EV- Positive Samples (%) | EV-D68 Positive Samples (%) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2022 | 150 (22.9) | 20 (23.3) | |

| 2023 | 225 (28.7) | 4 (36.4) | <0.001 |

| 2024 | 163 (26.9) | 11 (9.2) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Hruskar, Z.; Skara Abramovic, L.; Ferencak, I.; Juric, D.; Lozic, J.; Juric, A.; Bocka, B.; Bajek, M.; Josipovic, M.; Bekic, V.; et al. Enterovirus-D68—Neglected Pathogen in Acute Respiratory Infections: Insights from Croatia. Pathogens 2026, 15, 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens15010048

Hruskar Z, Skara Abramovic L, Ferencak I, Juric D, Lozic J, Juric A, Bocka B, Bajek M, Josipovic M, Bekic V, et al. Enterovirus-D68—Neglected Pathogen in Acute Respiratory Infections: Insights from Croatia. Pathogens. 2026; 15(1):48. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens15010048

Chicago/Turabian StyleHruskar, Zeljka, Lucija Skara Abramovic, Ivana Ferencak, Dragan Juric, Josipa Lozic, Anita Juric, Bojana Bocka, Marin Bajek, Mirela Josipovic, Viktor Bekic, and et al. 2026. "Enterovirus-D68—Neglected Pathogen in Acute Respiratory Infections: Insights from Croatia" Pathogens 15, no. 1: 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens15010048

APA StyleHruskar, Z., Skara Abramovic, L., Ferencak, I., Juric, D., Lozic, J., Juric, A., Bocka, B., Bajek, M., Josipovic, M., Bekic, V., & Tabain, I. (2026). Enterovirus-D68—Neglected Pathogen in Acute Respiratory Infections: Insights from Croatia. Pathogens, 15(1), 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens15010048