Metabolomic Insights into MYMV Resistance: Biochemical Complexity in Mung Bean Cultivars

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material

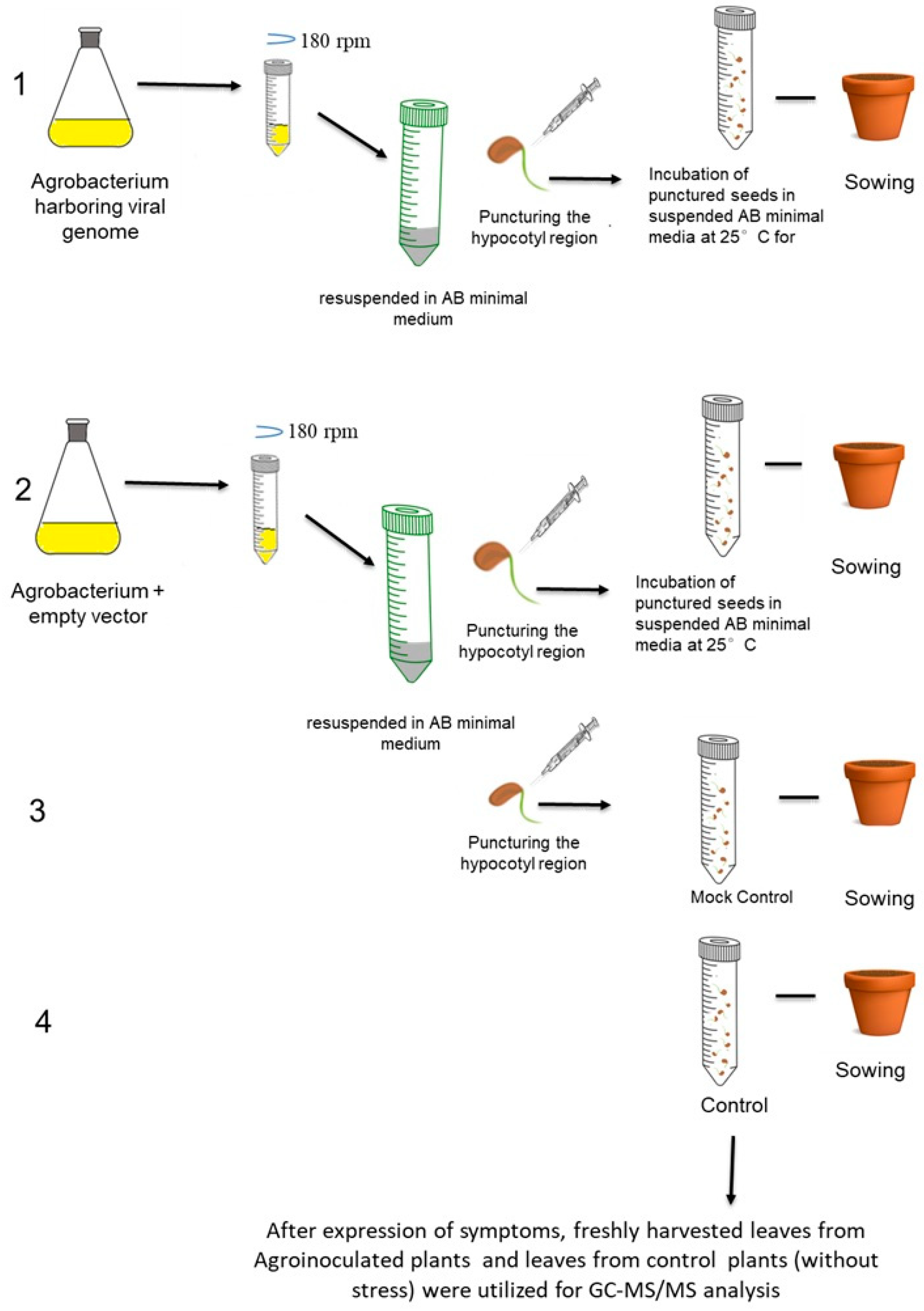

2.2. Agroinoculation

2.3. Extraction and Mass Spectrometric Analysis of Secondary Metabolites

2.4. Analysis and Pathway Mapping Using Statistical Methods

3. Results

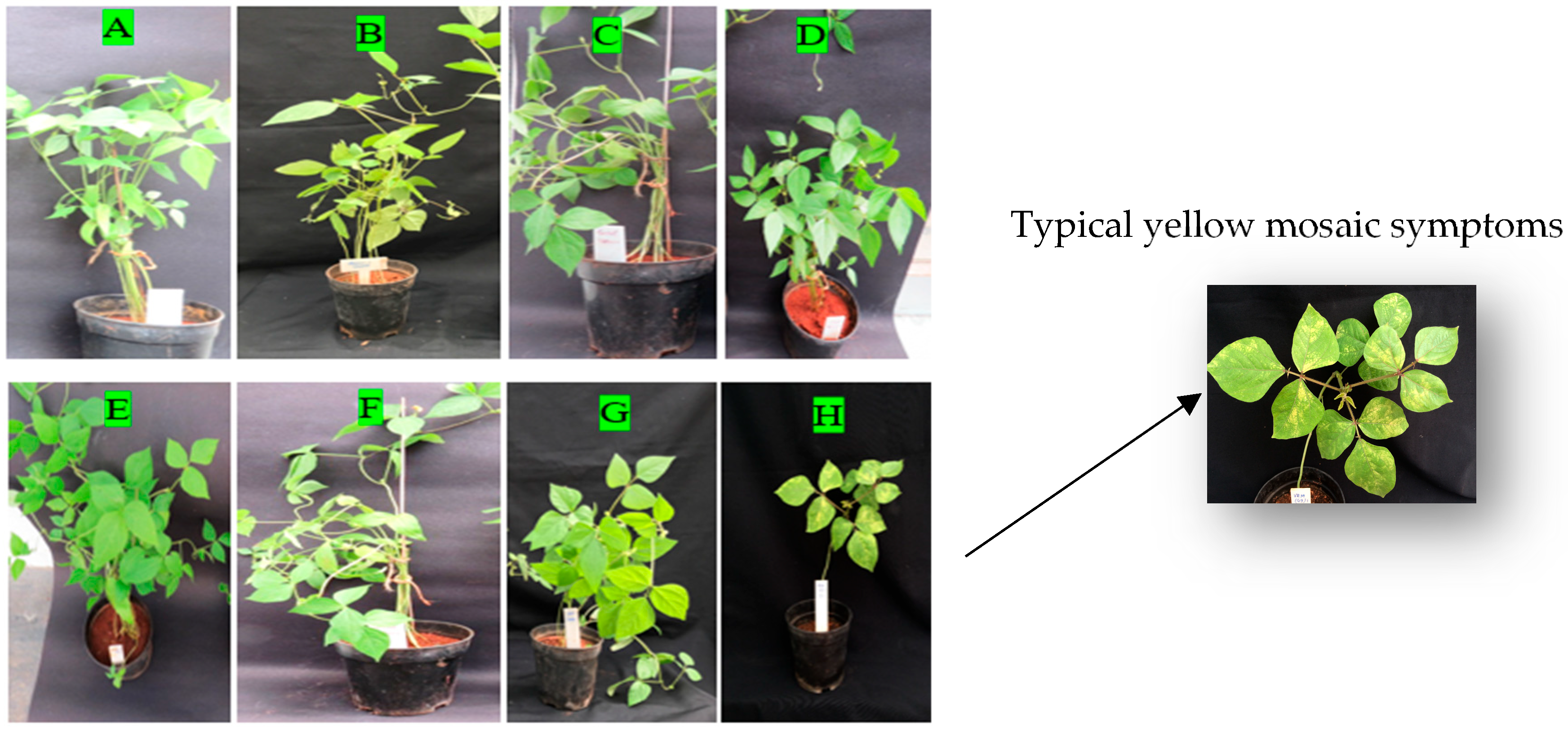

3.1. Agroinoculation Screening and Symptom Development

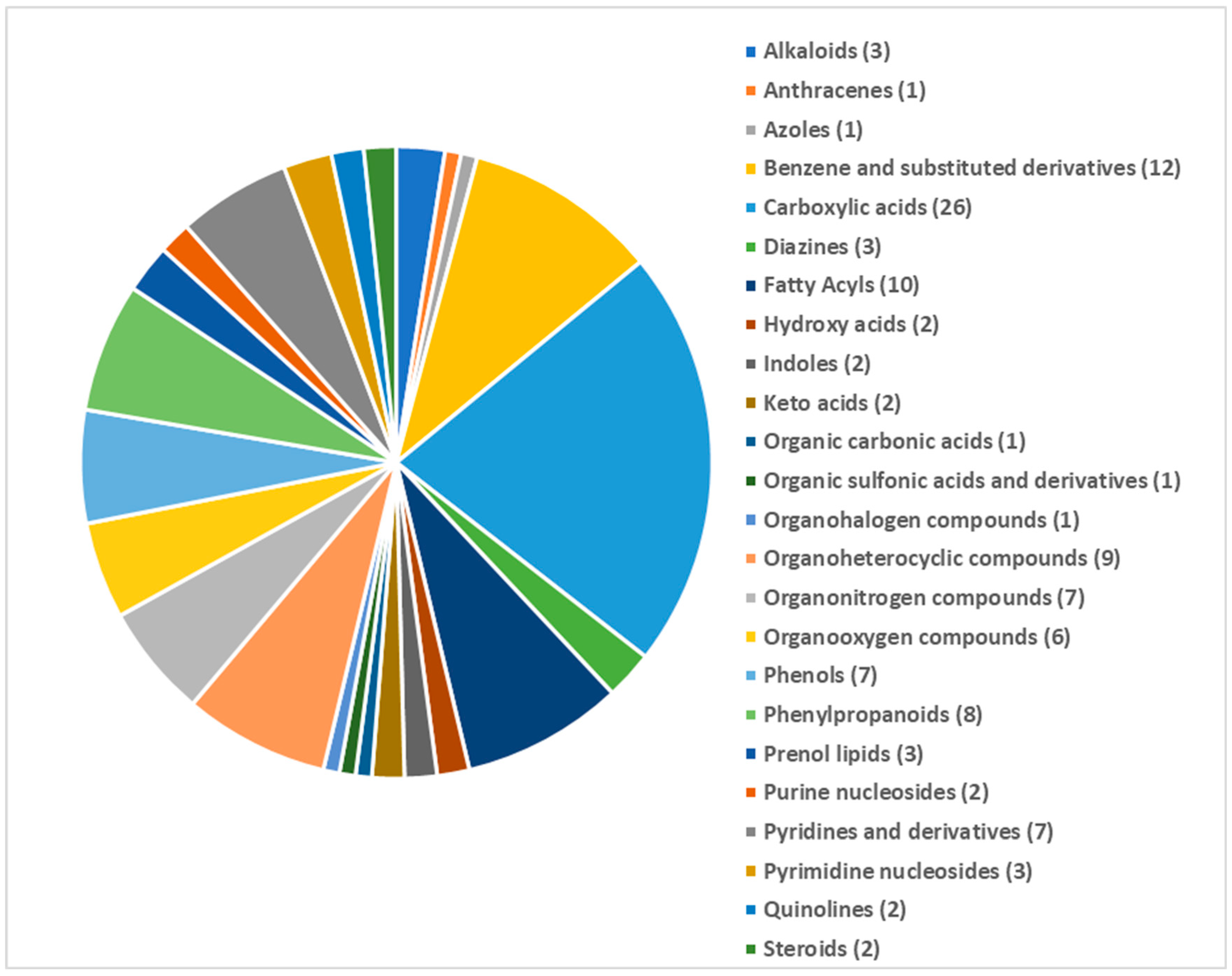

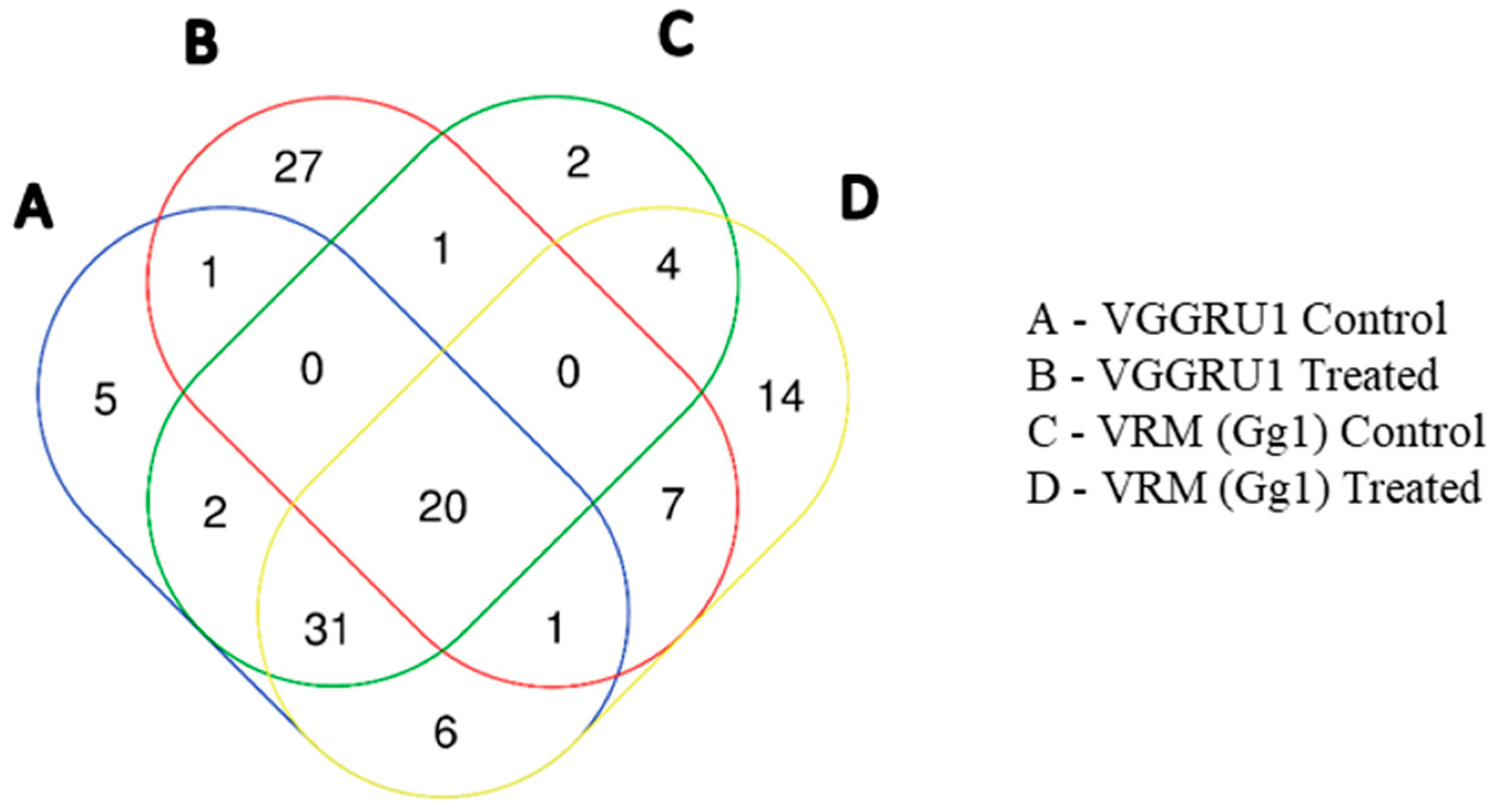

3.2. Metabolite Profiles of the Susceptible and Resistant Mung Bean Genotypes

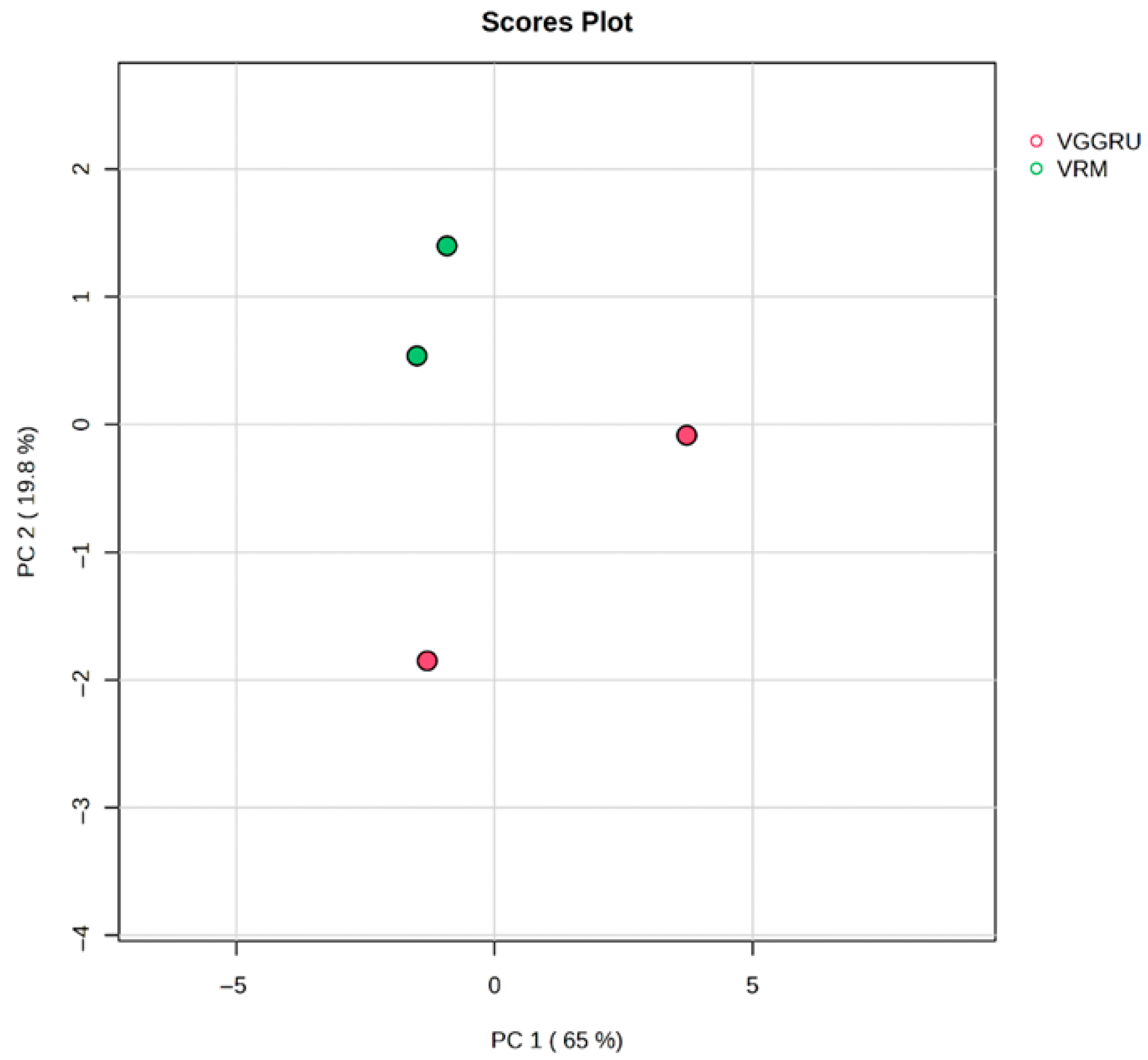

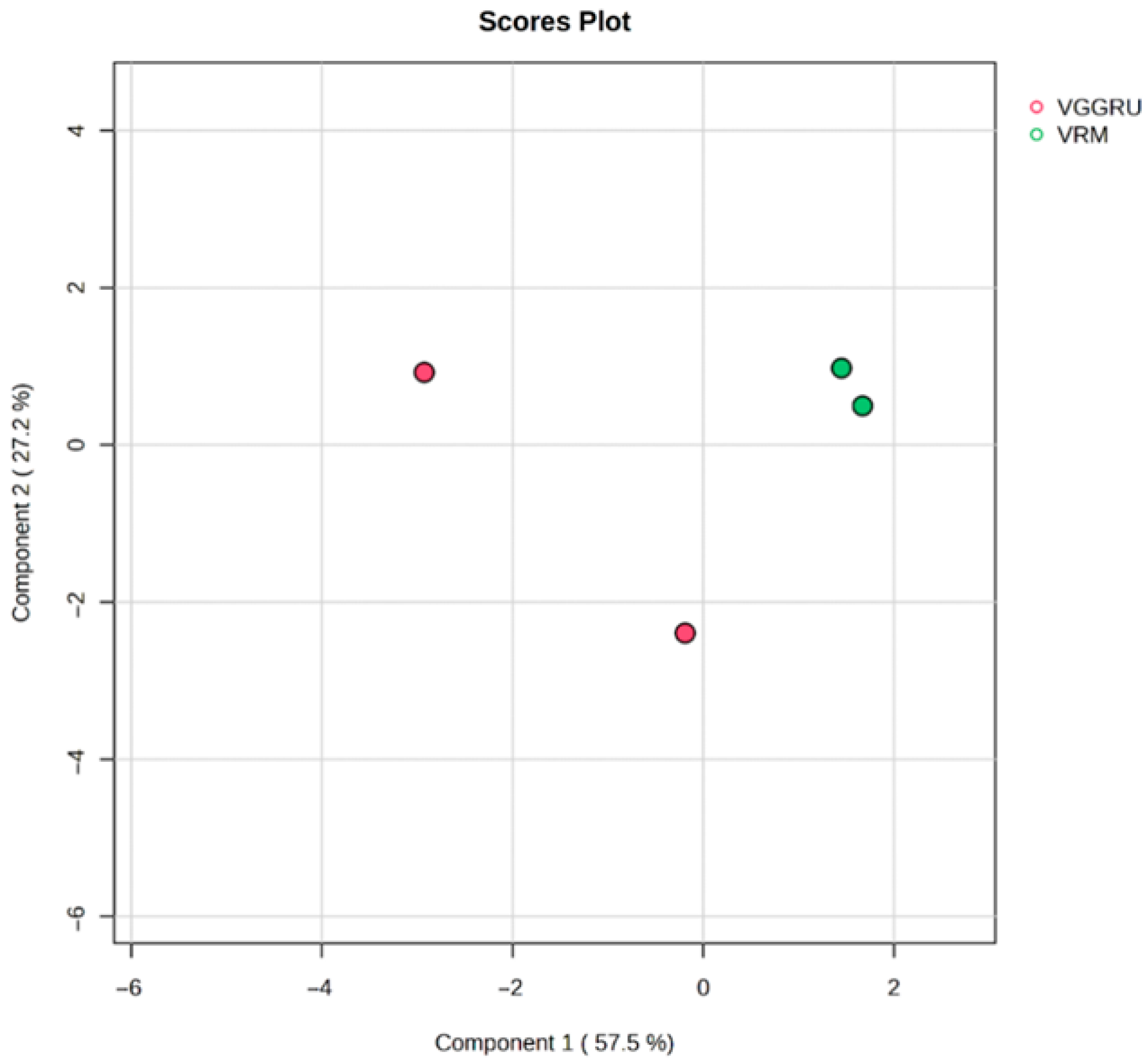

3.3. Chemometric Analysis

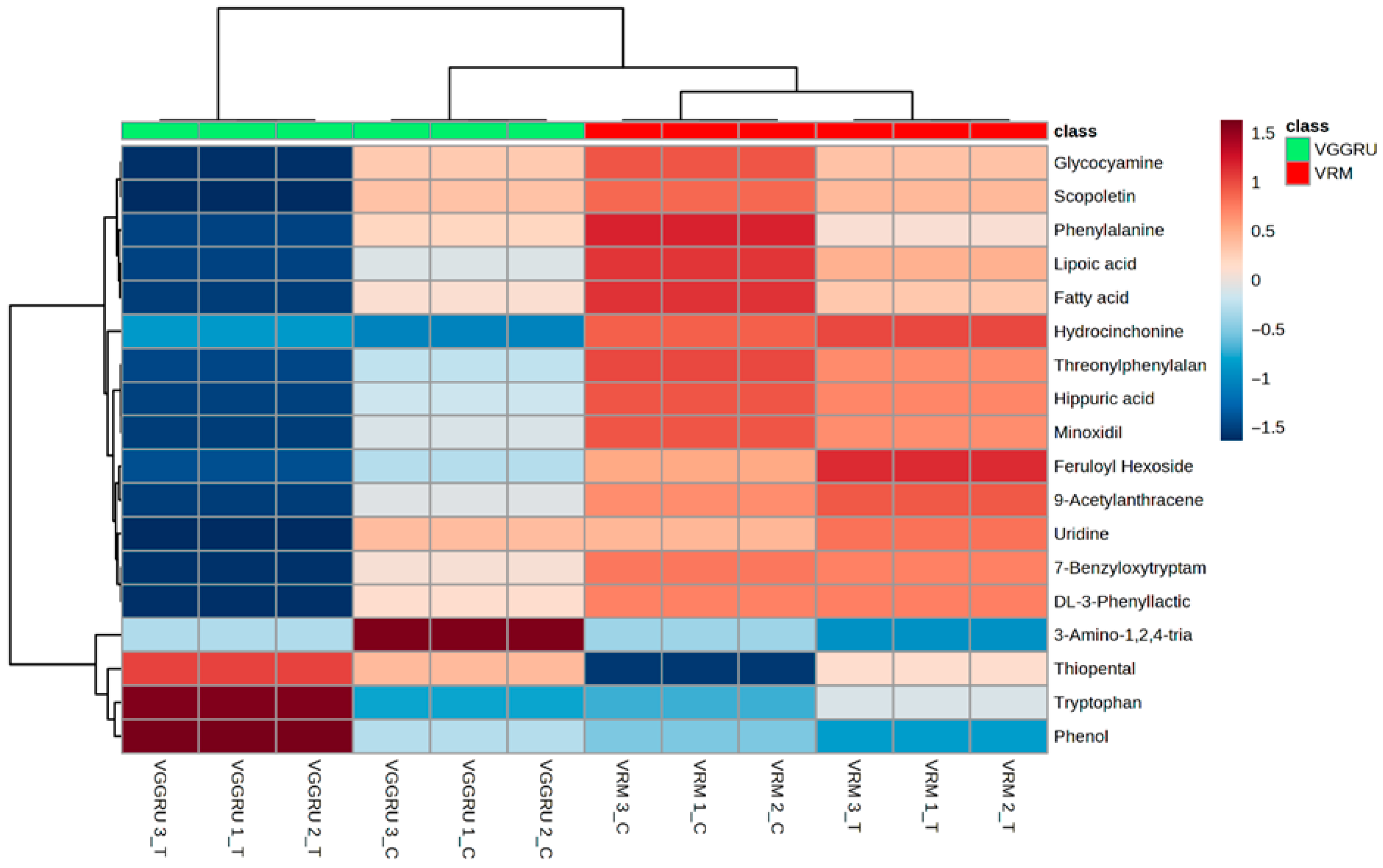

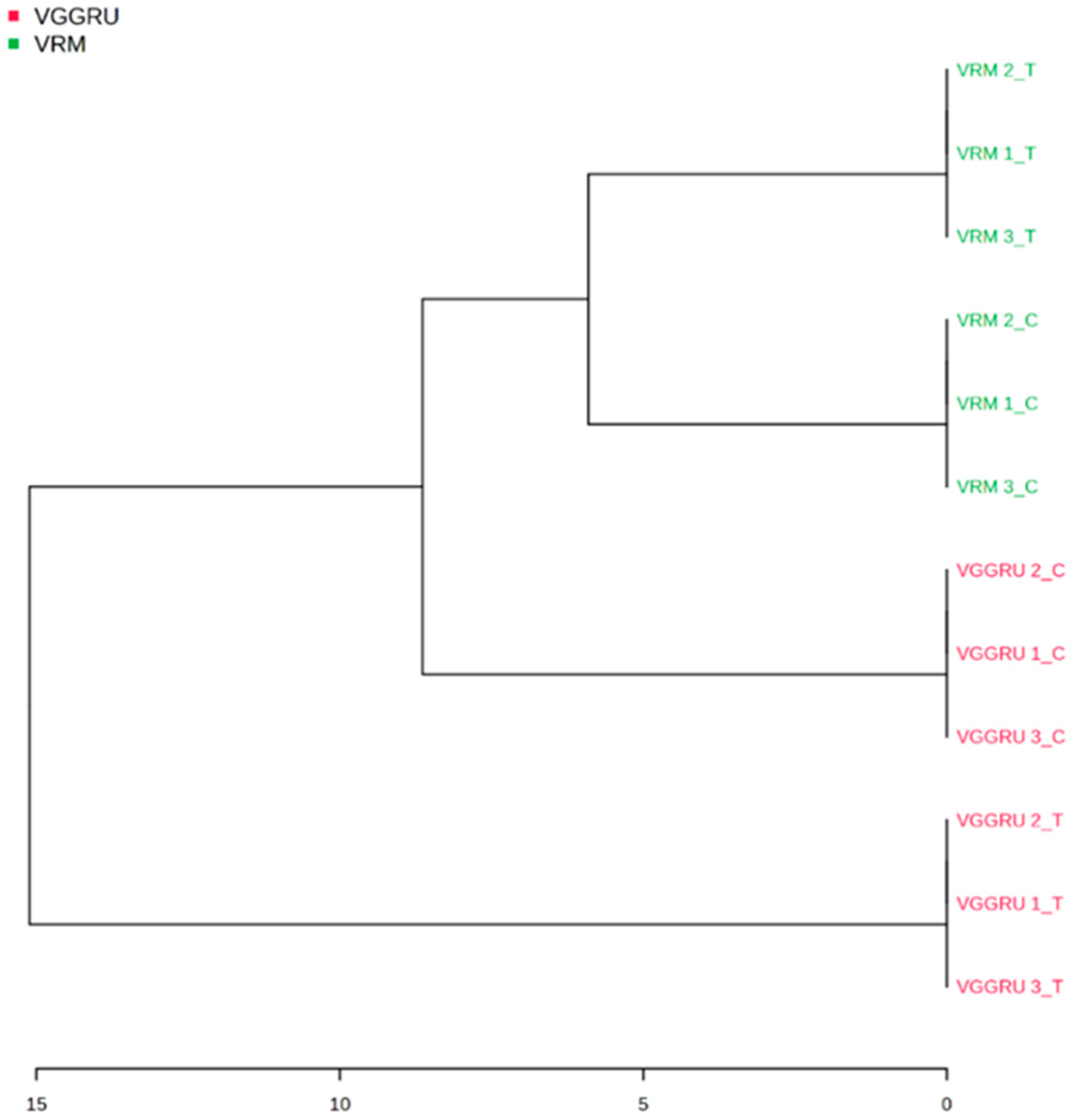

3.4. Hierarchial Clustering and Fold Change Analysis

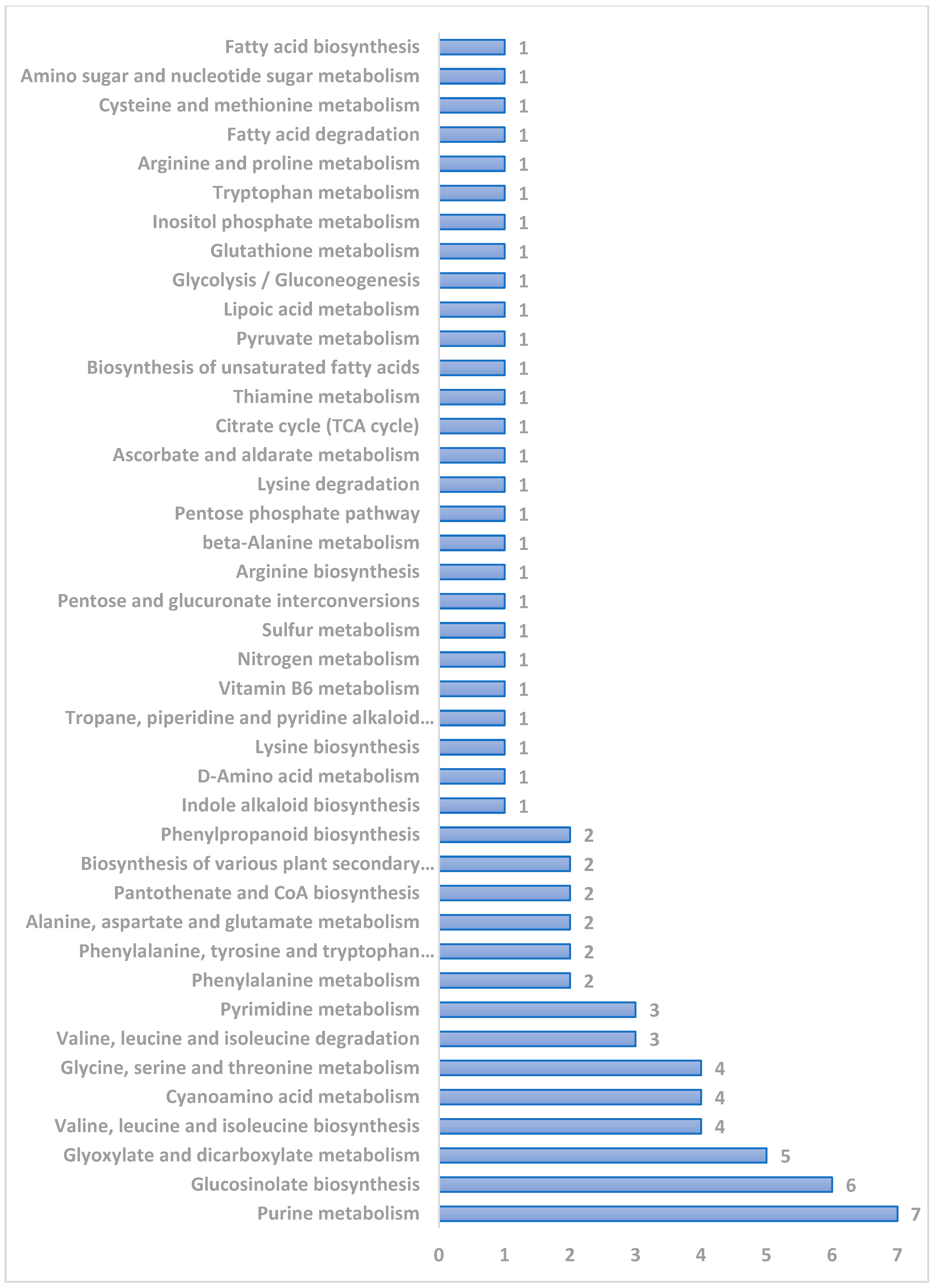

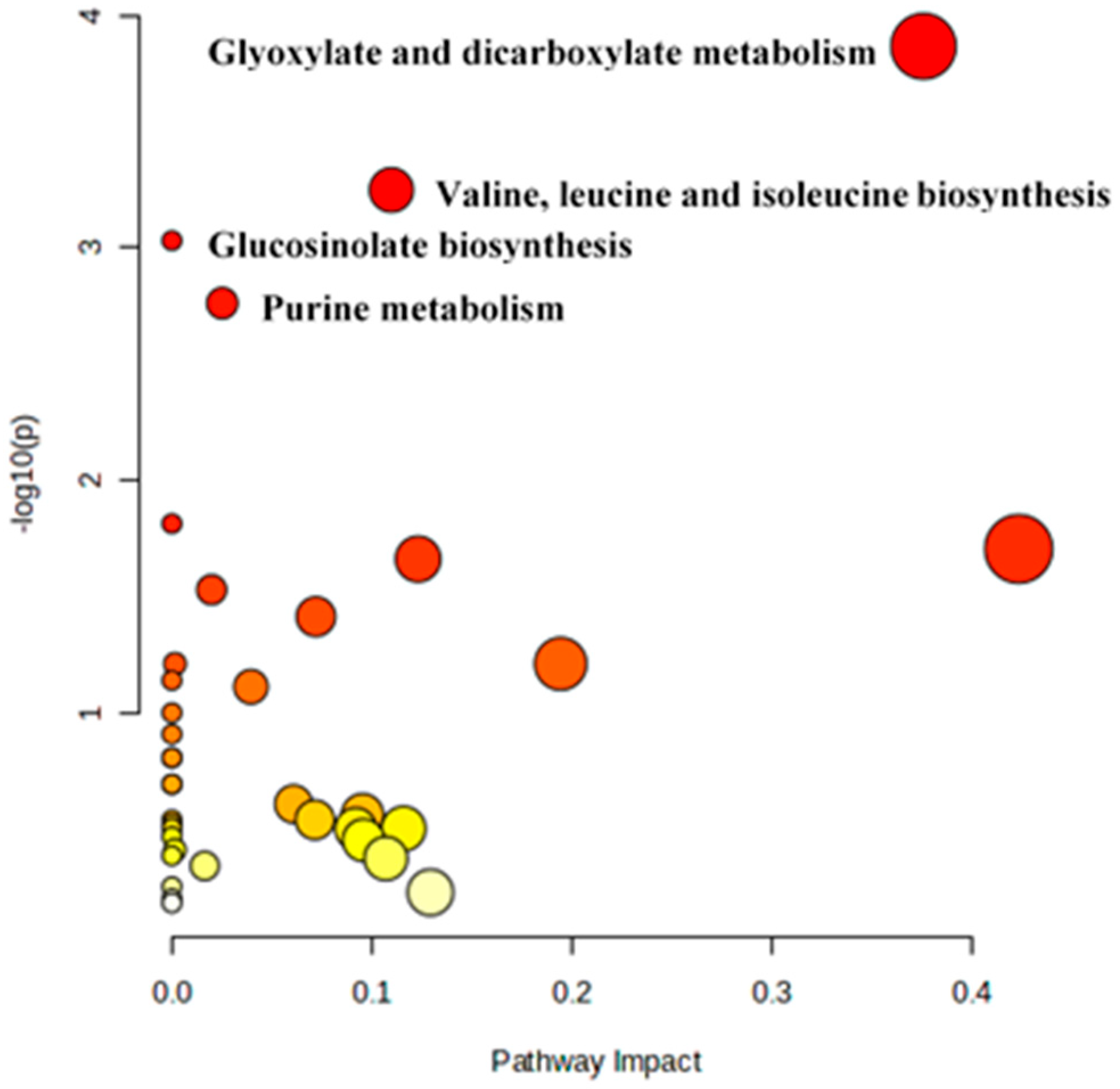

3.5. Pathway Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Selvi, R.; Muthiah, A.R.; Manivannan, N.; Raveendran, T.S.; Manickam, A.; Samiyappan, R. Tagging of RAPD marker for MYMV resistance in mungbean [Vigna radiata (L.) Wilczek]. Asian J. Plant Sci. 2006, 5, 277–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vairam, N.; Lavanya, S.A.; Muthamilan, M.; Vanniarajan, C. Screening of M3 mutants for yellow vein mosaic virus resistance in greengram [Vigna radiata (L.) Wilczek]. Int. J. Plant Sci. 2016, 11, 265–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, R.M.; Yang, R.Y.; Easdown, W.J.; Thavarajah, D.; Thavarajah, P.; Hughes, J.D.; Keatinge, J.D. Biofortification of mung bean (Vigna radiata) as a whole food to enhance human health. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2013, 93, 1805–1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karthikeyan, A.S.; Vanitharani, R.; Balaji, V.; Anuradha, S.; Thillaichidambaram, P.; Shivaprasad, P.V.; Parameswari, C.; Balaman, V.; Saminathan, M.; Veluthambi, K. Analysis of an isolate of mungbean yellow mosaic virus (MYMV) with a highly variable DNA B component. Arch. Virol. 2004, 149, 1643–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usharani, K.S.; Surendranath, B.; Haq, Q.M.R.; Malathi, V.G. Yellow mosaic virus infecting soybean in Northern India is distinct from the species infecting soybean in southern and western India. Curr. Sci. 2004, 86, 845850. [Google Scholar]

- Ramesh, S.V.; Chouhan, B.S.; Ramteke, R. Molecular detection of Begomovirus (family: Geminiviridae) infecting Glycine max (L.) Merr. And associated weed Vigna trilobata. J. Crop Weed 2017, 13, 64–67. [Google Scholar]

- Dikshit, H.K.; Mishra, G.P.; Somta, P.; Shwe, T.; Alam, A.K.M.M.; Bains, T.S. Classical genetics and traditional breeding in mung bean. In The Mungbean Genome Compendium of Plant Genomes; Nair, R.M., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamireddy, R.; Lakra, N.; Ahlawat, Y.; Sundaramoorthy, M.; Menon, S.V.; Manorama, K.; Upadhyay, S.K. Integrated Morphological, Biochemical and Molecular Screening of Mungbean (Vigna radiata L.) Genotypes for Mungbean Yellow Mo saic Virus (MYMV) Resistance. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2025, 229, 110596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deepa, H.; Govindappa, M.R.; Kenganal, M.; Kulkarni, S.A.; Biradar, S.A. Screening of greengram genotypes against Mungbean Yellow Mosaic Virus diseases under field condition. Int. J. Pure Appl. Biosci. 2017, 5, 1049–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karthikeyan, A.; Shobhana, V.G.; Sudha, M.; Raveendran, M.; Senthil, N.; Pandiyan, M.; Nagarajan, P. Mungbean yellow mosaic virus (MYMV): A threat to green gram (Vigna radiata) production in Asia. Int. J. Pest. Manag. 2014, 60, 314–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, R.M.; Gotz, M.; Winter, S.; Giri, R.R.; Boddepalli, V.N.; Sirari, A.; Bains, T.S.; Taggar, G.K.; Dikshit, H.K.; Aski, M.; et al. Identification of mungbean lines with tolerance or resistance to yellow mosaic in fields in India where different begomovirus species and different Bemisia tabaci cryptic species predominate. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2017, 42, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A.K.; Arya, R.; Tyagi, R.; Grover, D.; Mishra, J.; Vimal, S.R.; Mishra, S.; Sharma, S. Non-judicious use of pesticides indicating potential threat to sustainable agriculture. In Sustainable Agriculture Reviews 50: Emerging Contaminants in Agriculture; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 383–400. [Google Scholar]

- Sudha, M.; Karthikeyan, A.; Nagarajan, P.; Raveendran, M.; Senthil, N.; Pandiyan, M.; Angappan, K.; Ramalingam, J.; Bharathi, M.; Rabindran, R.; et al. Screening of mungbean (Vigna radiata) germplasm for resistance to Mungbean yellow mosaic virus using agroinoculation. Can. J. Plant Pathol. 2013, 35, 424–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhumitha, B.; Aiyanathan, K.E.A.; Raveendran, M.; Sudha, M. Identification and confirmation of resistance in mung bean [Vigna radiata (L.) Wilczek] derivatives to mungbean yellow mosaic virus (MYMV). Legum. Res. 2022, 45, 122–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, A.K.; Jhamaria, S.L. Evaluation of mungbean (Vigna radiata L.) varieties to yellow mosaic virus. J. Mycol. Pl. Pathol. 2004, 34, 64–65. [Google Scholar]

- Salam, S.A.; Patil, M.S.; Byadgi, A.S. Integrated disease management of Mungbean Yellow Mosaic Virus. Ann. Plant Prot. Sci. 2009, 17, 157–160. [Google Scholar]

- Basavaraj, S.; Padmaja, A.S.; Nagaraju, N.; Ramesh, S. Identification of stable sources of resistance to mung bean yellow mosaic virus (MYMV) disease in mung bean [Vigna radiata (L.) Wilczek]. Plant Genet. Resour. 2019, 17, 362–370. [Google Scholar]

- Khattak, G.S.S.; Saeed, I.; Shah, S.A. Breeding high yielding and disease resistant mungbean (Vigna radiata (L.) Wilczek) genotypes. Pak. J. Bot. 2008, 40, 1411–1417. [Google Scholar]

- Akhtar, K.P.; Sarwar, G.; Abbas, G.; Asghar, M.J.; Sarwar NShah, T.M. Screening of mung bean germplasm against mung bean yellow mosaic India virus and its vector Bemisia tabaci. Crop Prot. 2011, 30, 1202–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasubramaniam, M.; Thangavel, T.; Aiyanathan, K.E.A.; Rathnasamy, S.A.; Rajagopalan, V.R.; Subbarayalu, M.; Natesan, S.; Kanagarajan, S.; Muthurajan, R.; Manickam, S. Manickam Unveiling mungbean yellow mosaic virus: Molecular insights and infectivity validation in mung bean (Vigna radiata) via infectious clones. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1401526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, S.; Vanitharani, R.; Karthikeyan, A.; Chinchore, Y.; Thillaichidambaram, P.; Veluthambi, K. Mungbean yellow mosaic virus-Vi agroinfection by codelivery of DNA A and DNA B from one Agrobacterium strain. Plant Dis. 2003, 87, 247–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramalingam, A.P.; Mohanavel, W.; Premnath, A.; Muthurajan, R.; Prasad, P.; Perumal, R. Large-Scale Non-Targeted Metabolomics Reveals Antioxidant, Nutraceutical and Therapeutic Potentials of Sorghum. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pang, Z.; Chong, J.; Zhou, G.; de Lima Morais, D.A.; Chang, L.; Barrette, M.; Gauthier, C.; Jacques, P.É.; Lin, S.; Xia, J. Metabo Analyst 5.0: Narrowing the gap between raw spectra and functional insights. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, 388–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanehisa, M.; Sato, Y.; Kawashima, M.; Furumichi, M.; Tanabe, M. KEGG as a reference resource for gene and protein annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, 457–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, B.C.; Yeam, I.; Jahn, M.M. Genetics of plant virus resistance. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2005, 43, 581–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierre, R.E. Observation on golden mosaic of bean (Phaseolous vulgaris L.) in Jamaica. In Tropical Diseases of Legumes; Bird, J., Maramoroscheds, K., Eds.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1975; pp. 35–39. [Google Scholar]

- Muniyappa, V.; Rajeshwari, R.; Bharathan, N.; Reddy, D.V.R.; Nolt, B.L. Isolation and characterization of a geminivirus causing yellow mosaic disease of Horsegram (Macrotyloma uniflorum (Lam.) Verdc.) in India. J. Phytopathol. 1987, 119, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruthi, M.N.; Rekha, A.R.; Govindappa, M.R.; Colvin, J.; Muniyappa, V. A distinct begomovirus causes Indian dolichos yellow mosaic disease. Plant Pathol. 2006, 55, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamaal, N.; Akram, M.; Pratap, A.; Yadav, P. Characterization of a new begomovirus and a beta satellite associated with the leaf curl disease of French bean in Northern India. Virus Genes 2013, 46, 120–127. [Google Scholar]

- Ansar, M.; Agnihotri, A.K.; Akram, M.; Bhagat, A.P. First report of Tomato leaf curl Joydebpur virus infecting French bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.). J. Gen. Plant Pathol. 2019, 85, 444–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkataravanappa, V.; Prasanna, H.C.; Reddy, C.N.L.; Chauhan, N.; Shankarappa, K.S.; Krishnareddy, M. Molecular characterization of recombinant Bipartite begomovirus associated with mosaic and leaf curl disease of Cucumber and Muskmelon. Indian Phytopathol. 2021, 74, 775–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundu, A.; Singh, P.K.; Dey, A. Complex molecular mechanisms underlying MYMIV-resistance in Vigna mungo revealed by comparative transcriptome profiling. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 8858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudha, M.; Karthikeyan, A.; Shobhana, V.; Nagarajan, P.; Raveendran, M.; Senthil, N.; Pandiyan, M.; Angappan, K.; Balasubramanian, P.; Rabindran, R. Search for Vigna species conferring resistance to mungbean yellow mosaic virus in mung bean. Plant Genet. Resour. 2015, 13, 162–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashiwaba, K.; Tomooka, N.; Kaga, A.; Han, O.K.; Vaughan, D.A. Characterization of resistance to three bruchid species (Callosobruchus spp., Coleoptera, Bruchidae) in cultivated rice bean (Vigna umbellata). J. Econ. Entomol. 2003, 96, 207–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.K.; Sood, P.; Prasad, A.; Prasad, M. Advances in omics technology for improving crop yield and stress resilience. Plant Breed. 2021, 140, 719–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhumitha, B.; Aiyanathan, K.E.A.; Sudha, M. Coat protein-based characterization of Mungbean yellow mosaic virus in Tamil Nadu. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem. 2019, 8, 2119–2123. [Google Scholar]

- Palego, L.; Betti, L.; Rossi, A.; Giannaccini, G. Tryptophan biochemistry: Structural, nutritional, metabolic, and medical aspects in humans. J. Amino Acid. 2016, 2016, 8952520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedras, M.S.; Yaya, E.E.; Glawischnig, E. The phytoalexins from cultivated and wild crucifers: Chemistry and biology. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2011, 28, 1381–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Won, C.; Shen, X.; Mashiguchi, K.; Zheng, Z.; Dai, X.; Cheng, Y.; Kasahara, H.; Kamiya, Y.; Chory, J.; Zhao, Y. Conversion of tryptophan to indole-3-acetic acid by tryptophan aminotransferases of Arabidopsis and yuccas in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 18518–18523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lynch, J.H.; Qian, Y.; Guo, L.; Maoz, I.; Huang, X.Q.; Garcia, A.S.; Louie, G.; Bowman, M.E.; Noel, J.P.; Morgan, J.A.; et al. Modulation of auxin formation by the cytosolic phenylalanine biosynthetic pathway. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2020, 16, 850–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahuja, I.; Kissen, R.; Bones, A.M. Phytoalexins in defense against pathogens. Trends Plant Sci. 2012, 17, 73–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Chandrawat, K.S. Role of Phytoalexins in Plant Disease Resistance. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. App Sci. 2017, 6, 125–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Vallet, A.; Ramos, B.; Bednarek, P.; López, G.; Pislewska-Bednarek, M.; Schulze-Lefert, P.; Molina, A. Tryptophan-derived secondary metabolites in Arabidopsis thaliana confer non-host resistance to necrotrophic Plectosphaerella cucumerina fungi. Plant J. 2010, 63, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burow, M.; Halkier, B.A. How does a plant orchestrate defense in time and space? Using glucosinolates in Arabidopsis as case study. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2017, 38, 142–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiruma, K. Roles of Plant-Derived Secondary Metabolites during Interactions with Pathogenic and Beneficial Microbes under Conditions of Environmental Stress. Microorganisms 2019, 7, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gundersen, R.Y.; Vaagenes, P.; Breivik TFonnum, F.; Opstad, P.K. Glycine-An important neurotransmitter and cytoprotective agent. Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand. 2005, 49, 1108–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, R.A.; Achnine, L.; Kota, P.; Liu, C.J.; Reddy, M.S.; Wang, L. The phenylpropanoid pathway and plant defence—A genomics perspective. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2002, 3, 371–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stout, M.J.; Thaler, J.S.; Thomma, B.P. Plant-mediated interactions between pathogenic microorganisms and herbivorous arthropods. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2006, 51, 663–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallis, C.M.; Galarneau, E.R. Phenolic Compound Induction in Plant-Microbe and Plant-Insect Interactions: A Meta- Analysis. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 580753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vogt, T. Phenylproapanoid biosynthesis. Mol. Plant 2010, 3, 2–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.R.; Tang, K.; Liu, H.T.; Huang, W.D. Effect of salicylic acid on jasmonic acid-related defense response of pea seedlings to wounding. Sci. Hort. 2011, 128, 166–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Deng, Y.; Yu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Chi, D. A study on JA- and BTH-induced resistance of Rosa rugosa ‘Plena’ to powdery mildew (Sphaerotheca pannosa). J. Res. 2018, 29, 823–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.T.; Lee, B.R.; La, V.H.; Lee, H.; Jung, W.J.; Bae, D.W.; Kim, T.H. p-Courmaric acid induces jasmonic acid-mediated phenolic accumulation and resistance to black rot disease in Brassica napus. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2019, 106, 270–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyer, S.F.; Beesley, A.; Rohmann, P.F.; Schultheiss, H.; Conrath ULangenbach, C.J. The Arabidopsis non-host defence-associated coumarin scopoletin protects soybean from Asian soybean rust. Plant J. 2019, 99, 397–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chong, J.; Baltz, R.; Schmitt, C.; Beffa, R.; Fritig BSaindrenan, P. Downregulation of a pathogen-responsive tobacco UDP-Glc: Phenylpropanoid glucosyltransferase reduces scopoletin glucoside accumulation, enhances oxidative stress, and weakens virus resistance. Plant Cell 2002, 14, 1093–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Oirdi, M.; Trapani, A.; Bouarab, K. The nature of tobacco resistance against Botrytis cinerea depends on the infection structures of the pathogen. Env. Microbiol. 2010, 12, 239–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.; Yang, F.; Wang, Y.; Li, S.; Zhang, D.; Liang, W.; Yang, Q. Scopoletin negatively regulates the HOG pathway and exerts antifungal activity against Botrytis cinerea by interfering with infection structures, cell wall, and cell membrane formation. Phytopathol. Res. 2024, 6, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agati, G.; Brunetti, C.; Tuccio, L.; Degano, I.; Tegli, S. Retrieving the in vivo Scopoletin Fluorescence Excitation Band Allows the Non-invasive Investigation of the Plant–Pathogen Early Events in Tobacco Leaves. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 889878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Sharma, A.; Sharma, A.; Kumar, Y.; Sharma, P.; Bhardwaj, R.; Sharma, I. Polyphenol phytoalexins as the determinants of plant disease resistance. In Plant Phenolics in Biotic Stress Management; Springer Nature Singapore: Singapore, 2024; pp. 243–274. [Google Scholar]

- Prats, E.; Llamas, M.J.; Jorrin, J.; Rubiales, D. Constitutive coumarin accumulation on sunflower leaf surface prevents rust germ tube growth and appressorium differentiation. Crop Sci. 2007, 47, 1119–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Wang, L.; Zhang, B.; Ma, J.; Hettenhausen, C.; Cao, G.; Sun, G.; Wu, J.; Wu, J. Scopoletin is a phytoalexin against Alternaria alternata in wild tobacco dependent on jasmonate signalling. J. Exp. Bot. 2014, 65, 4305–4315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verbruggen, N.; Hermans, C. Proline accumulation in plants: A review. Amino Acids 2008, 35, 753–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabro, G.; Kovács, I.; Pavet, V.; Szabados, L.; Alvarez, M.E. Proline accumulation and AtP5CS2 gene activation are induced by plant-pathogen incompatible interactions in Arabidopsis. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2004, 17, 343–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Cultivar | Origin | Days of Maturity | Pedigree | Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VGGRU1 | TNAU, Coimbatore, India | 60–75 days | High-level MYMV-resistant derivative of Vigna radiata × Vigna umbellata | MYMV resistant |

| VRM (Gg)1 | TNAU, Coimbatore, India | 56–67 days | Pure line selection from K 851 | MYMV susceptible |

| S. No | Compound Name | Fold Change | Log 2 (Fold Change) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Tryptophan | 17.102 | 4.0961 |

| 2. | 3-Amino-1,2,4-triazole | 15.478 | 3.9522 |

| 3. | Phenol | 6.4135 | 2.6811 |

| 4. | Cyprodinil | 3.4521 | 1.7875 |

| 5. | 2-Amino-3-methylimidazo(4,5-f) quinoline | 2.7709 | 1.4703 |

| 6. | Diethyldiallylmalonate | 2.5143 | 1.3301 |

| 7. | Glycine | 2.4229 | 1.2768 |

| 8. | Hypoxanthine | 2.0405 | 1.0289 |

| 9. | Scopoletin | 0.49484 | −1.015 |

| 10. | Proline | 0.4582 | −1.1259 |

| 11. | Phenylalanine | 0.38899 | −1.3622 |

| 12. | DL-3-Phenyllactic acid | 0.36861 | −1.4398 |

| 13. | 7-Benzyloxytryptamine | 0.3423 | −1.5467 |

| 14. | 9-Octadecanoic acid | 0.33494 | −1.578 |

| 15. | 9-Acetylanthracene | 0.25516 | −1.9705 |

| 16. | Minoxidil | 0.24339 | −2.0387 |

| 17. | Lipoic acid | 0.24194 | −2.0473 |

| 18. | Hippuric acid | 0.20954 | −2.2547 |

| 19. | Hydrocinchonine | 0.18042 | −2.4706 |

| 20. | Threonylphenylalanine | 0.17216 | −2.5382 |

| 21. | Feruloyl Hexoside | 0.13926 | −2.8442 |

| S. No | Pathway | Raw p Value | −log(p) | FDR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Glyoxylate and dicarboxylate metabolism | 0.000136 | 3.866 | 0.012388 |

| 2. | Valine, leucine, and isoleucine biosynthesis | 0.000565 | 3.248 | 0.025707 |

| 3. | Glucosinolate biosynthesis | 0.000933 | 3.0302 | 0.028296 |

| 4. | Purine metabolism | 0.001734 | 2.7611 | 0.039438 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Manickam, S.; Rajagopalan, V.R.; Balasubramaniam, M.; Adhimoolam, K.; Natesan, S.; Muthurajan, R. Metabolomic Insights into MYMV Resistance: Biochemical Complexity in Mung Bean Cultivars. Pathogens 2026, 15, 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens15010046

Manickam S, Rajagopalan VR, Balasubramaniam M, Adhimoolam K, Natesan S, Muthurajan R. Metabolomic Insights into MYMV Resistance: Biochemical Complexity in Mung Bean Cultivars. Pathogens. 2026; 15(1):46. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens15010046

Chicago/Turabian StyleManickam, Sudha, Veera Ranjani Rajagopalan, Madhumitha Balasubramaniam, Karthikeyan Adhimoolam, Senthil Natesan, and Raveendran Muthurajan. 2026. "Metabolomic Insights into MYMV Resistance: Biochemical Complexity in Mung Bean Cultivars" Pathogens 15, no. 1: 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens15010046

APA StyleManickam, S., Rajagopalan, V. R., Balasubramaniam, M., Adhimoolam, K., Natesan, S., & Muthurajan, R. (2026). Metabolomic Insights into MYMV Resistance: Biochemical Complexity in Mung Bean Cultivars. Pathogens, 15(1), 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens15010046