4.1. HIV-1 Env Fusion Subunit gp41

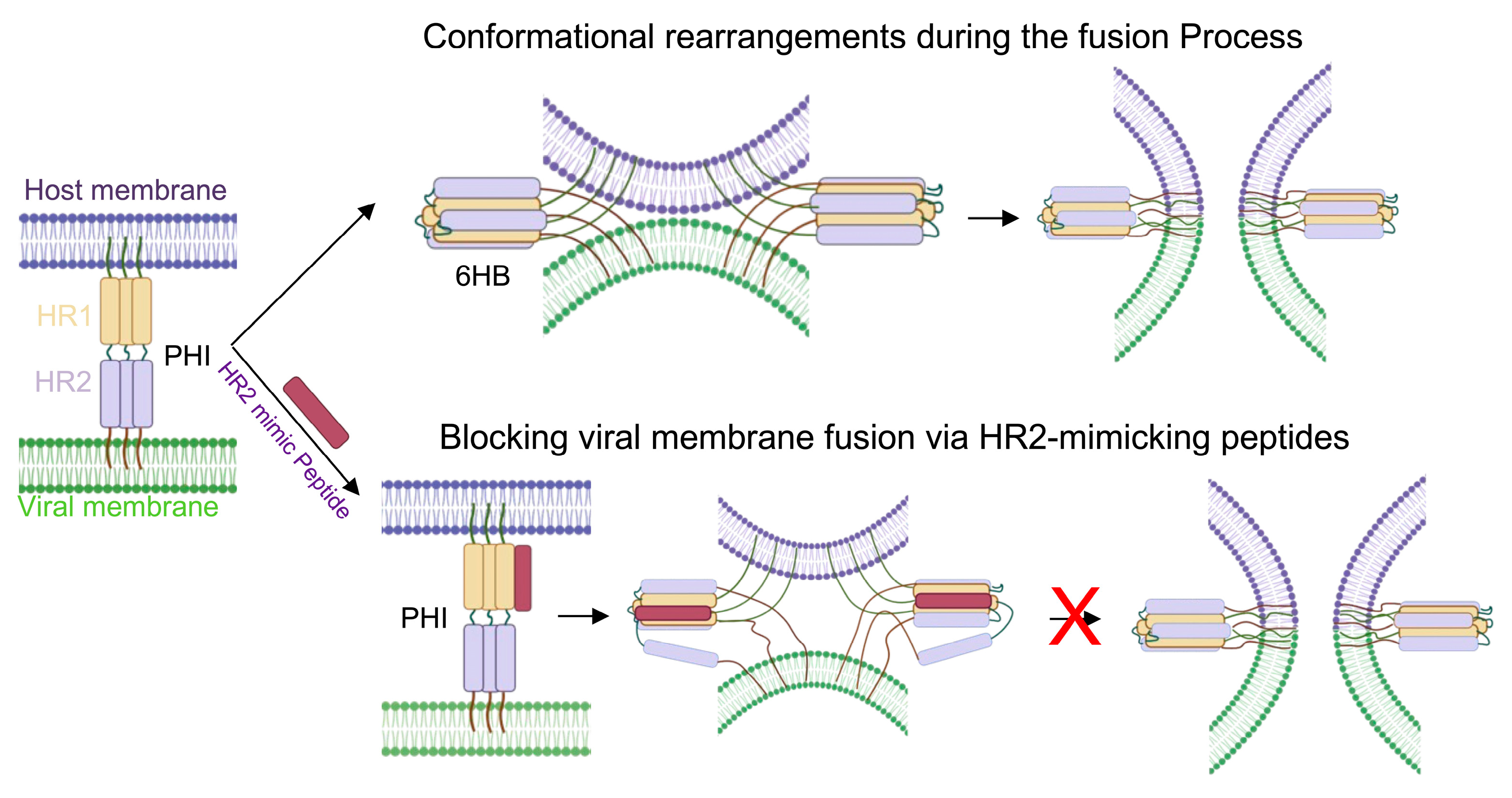

HIV-1 entry into host cells involves sequential binding of the envelope glycoprotein surface subunit gp120 to the host cell receptor CD4 and a coreceptor (CXCR4/CCR5), triggering conformational rearrangements in Env that expose the fusion subunit gp41 [

4,

13,

73,

74]. The gp41 fusion peptide then inserts into the host membrane and subsequently folds back on the C-terminal heptad repeat (HR) to form the 6HB: (HR1/HR2)

3, driving membrane fusion [

4,

13,

73]. This multistep mechanism established gp41 as a critical therapeutic target for blocking fusion. Currently, most peptide fusion inhibitors are derived from the gp41 HR1 and HR2 domains, especially HR2 [

75]. Early studies identified CS3, a peptide derived from the HR2 domain, prompting the development of additional gp41-derived fusion inhibitors, which, in turn, led to the generation and clinical approval of T20 [

63,

64,

76,

77]. Of note, structural characterization of gp41 revealed the canonical 6HB architecture, in which three HR2 helices pack antiparallel around a central HR1 coiled coil [

78,

79,

80]. The discovery of a deep hydrophobic pocket at the C-terminal end of HR1 provided a structural basis for rational inhibitor design, enabling peptide derivatives with markedly enhanced binding affinity (e.g., C34, Kd = 0.0007 nM vs. T20, Kd = 30 nM) [

81].

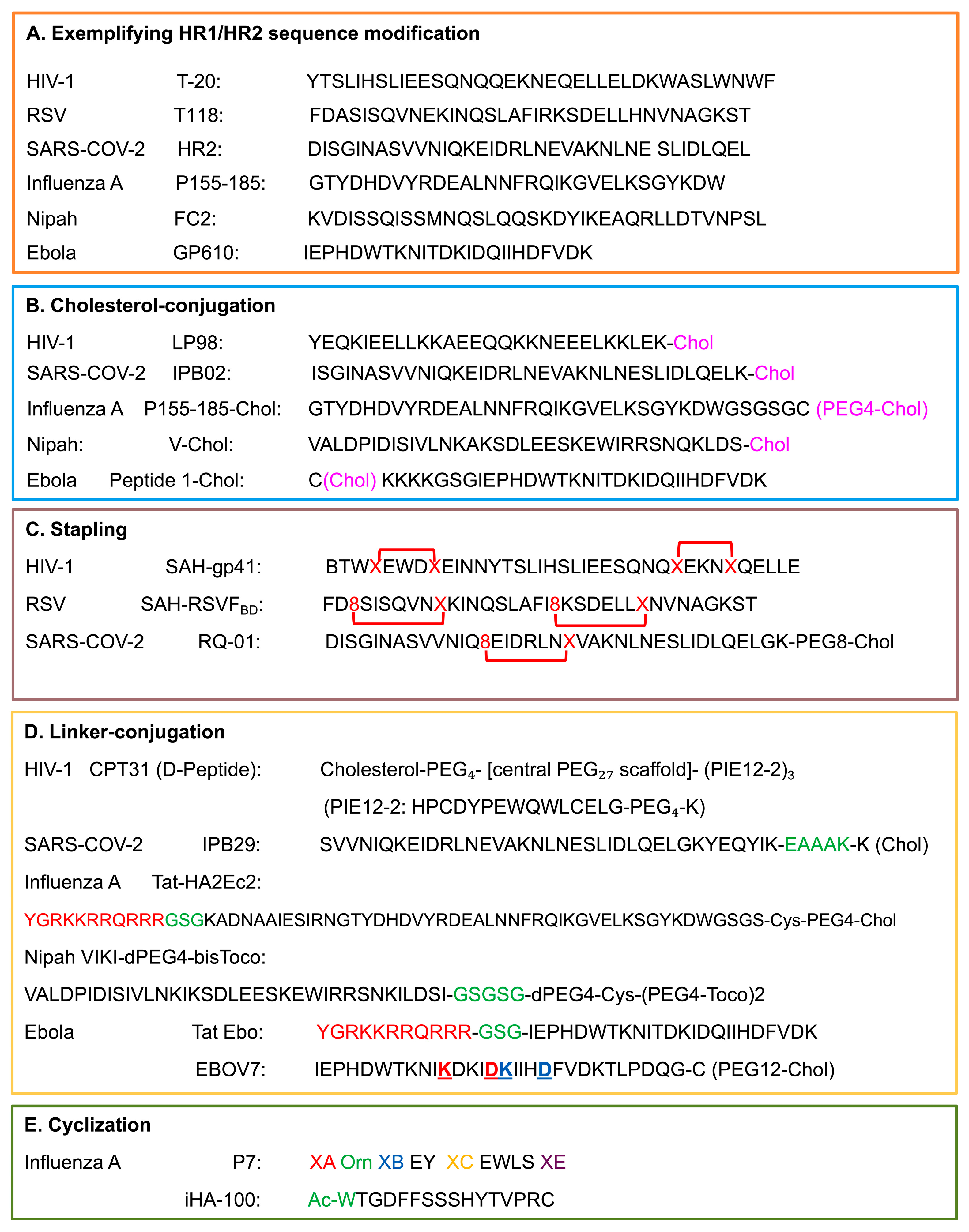

T20 in HIV-1 was the first proof-of-concept with clinical success for HR2-mimicking peptide inhibitors that block 6HB formation by preoccupying HR1 binding sites [

62,

63]. Derived from the HR2 region (amino acids 638–673), T20 (

Figure 4) contains an HR-binding domain (residues 638–666) that interacts with HR1, and a tryptophan-rich membrane-binding domain (residues 666–673) [

82]. Despite clinical validation, T20 exhibits moderate potency (IC

50 ~3 nM), rapid emergence of drug-resistant variants, a short plasma half-life, and notable adverse effects, such as injection-site reactions, peripheral neuropathy, etc., which ultimately lead to its discontinuation [

28,

83]. These shortcomings motivated the development of next-generation peptides. C34, a 34-residue peptide that engages the conserved HR1 hydrophobic pocket via its pocket-binding domain, achieves sub-nanomolar potency, remarkably improved binding affinity (Kd = 0.0007 nM vs. 30 nM for T20), and improved resistance profile [

5,

84].

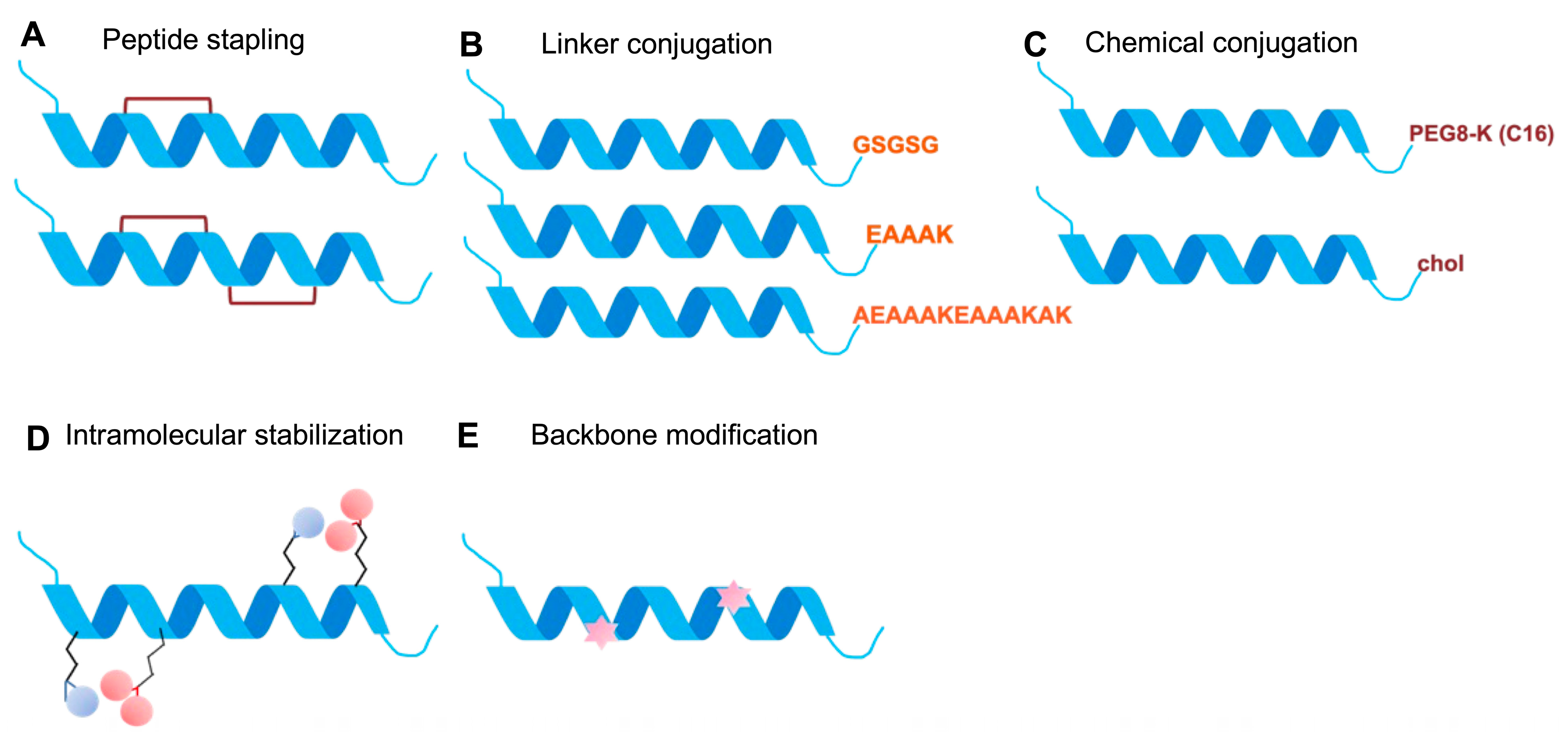

Second-generation inhibitors, such as T-1249 (tifuvirtide), combine pocket-binding features with extended HR sequences (C-terminal tryptophan-rich motif). Incorporating sequences from HIV-1, HIV-2, and SIV, T-1249 showed enhanced potency and activities against T20-resistant strains [

85,

86,

87,

88]. Meanwhile, efforts to introduce electrostatic stabilizing motifs (e.g., Glu–Arg ER pairs) and hydrocarbon stapling (SAH-gp41) (

Figure 4) [

89], increased 6-HB stability and plasma half-life [

90,

91]. Conjugating peptides to serum albumin to increase the plasma half-life through peptide residue modification with 3-Maleimidopropionic acid resulted in the design of albuvirtide (FB0006) [

92]. Efforts in detailed structure-activity refinement (SAR) further defined key structural determinants of activity, including the pocket-binding motif, helical stabilization requirements, and membrane-interaction elements [

86,

93]. Building on these principles, HP23, a rationally designed 23-residue peptide featuring an M-T hook structure [

94], demonstrated exceptional potency and retained activity against resistant mutants [

94,

95,

96,

97,

98]. This design strategy was also applied in the development of 2P23 and its derivatives [

98].

Lipid conjugation represented another milestone in enhancing peptide performance. Cholesterol conjugation significantly increased membrane affinity and stability, thereby establishing the membrane-targeting paradigm, as exemplified by C34-Chol, which exhibited 25–100-fold greater potency than C34 [

99,

100,

101]. A series of optimized lipopeptides, including LP-11, LP-19, LP-40, LP-46, LP-80, and LP-98 (

Figure 4), further improved potency into the picomolar range through lipid (fatty acids, cholesterol, sphingolipids, etc.) conjugation and refined linker chemistry [

102]. Among them, LP-98, currently in Phase II clinical trials, is the latest generation. Structural characterization revealed that LP-98 achieves exceptional potency through optimal clustering of hydrophobic residues, a network of 15 hydrogen bonds, two electrostatic interactions, and a salt bridge at the 6HB interface [

66].

Alternative conjugation approaches such as PEGylation have also been explored to improve peptide stability and solubility. N-terminal PEGylation of C34 (2 kDa and 5 kDa) significantly extended proteolytic stability while maintaining reasonable inhibitory activity [

103,

104]. Recent innovations have combined peptide fusion inhibitors with entry-targeting antibodies, such as 2P23-PRO140, a fusion construct that simultaneously targets CCR5 (via the PRO140 antibody) and gp41 (via the 2P23 peptide) [

105]. Dimerization of HR2 peptides, especially cholesterol-conjugated dimers, has also been shown to significantly enhance antiviral activity by increasing local concentration and binding avidity [

71]. Leveraging upon the enhanced potency achieved through HR2 dimerization strategies, next-generation approaches have enabled the use of D-peptide fusion inhibitor technology to address susceptibility by host L-proteases. CPT31 (

Figure 4), a D-peptide (trimer of PIE-12-2 with cholesterol moiety), exemplifies this approach. It has demonstrated potent antiviral efficacy in both in vitro and in vivo models and advanced to Phase I clinical evaluation [

106].

Beyond the well-characterized HR2-mediated inhibition pathway, HR1-derived fusion inhibitors have emerged as an alternative therapeutic approach, distinguished by their ability to disrupt the endogenous HR1 coiled-coil architecture itself rather than competitively blocking HR2 binding. N36, a prototypical 36-residue HR1-derived peptide [

107,

108,

109], demonstrated poor potency as a monomer (IC

50 ~16 μM) due to aggregation [

110,

111] and mixed oligomerization states [

112], making it 300–500 fold less potent than HR2 peptides like C34 [

109]. Engineering N36 into stable trimers via fusion to the GCN4-IQ coiled-coil domain (yielding IZN36) [

110] achieves ~500-fold enhancement in anti-fusion activity against R5-tropic viruses through stabilized trimeric assembly and improved HR2 binding [

112,

113].

HIV-1 fusion inhibitor optimization (

Table 1) follows a defined hierarchy, with strong HR1 pocket engagement preceding membrane anchoring, reflecting the unique fusion mechanism and structural constraints of Env [

114,

115]. Structure-guided targeting of the conserved hydrophobic HR1 pocket is critical for high-affinity binding, as exemplified by the HR2-derived peptide C34, which exhibits ~43,000-fold higher binding affinity than T20, yet only ~10-fold greater cellular antiviral potency, indicating that binding affinity and functional activity are not directly proportional. This principle guided the design of subsequent inhibitors, such as HP23, which incorporates an M–T hook motif, and LP-98, which forms extensive hydrogen-bonding and electrostatic interactions. Membrane anchoring, typically achieved via cholesterol conjugation, further enhances antiviral potency 25–100-fold by concentrating inhibitors at lipid-rich fusion sites. Refinement of linker flexibility and lipid optimization (cholesterol vs. fatty acids vs. sphingolipids) has enabled additional gains in activity, with LP-98 achieving sub-picomolar potency.

4.2. RSV F Protein

Similarly to HIV-1 Env, the F protein of RSV is metastable and undergoes spontaneous or stimulus-induced conformational changes from a prefusion to post-fusion form [

4]. Unlike the predominantly α-helical HIV-1 gp41, RSV F features a shorter six-helix bundle, distinct heptad repeat patterns, and a β-sheet propensity in the HR2 region [

33,

116]. The HR1 domain forms a stable trimeric coiled coil interacting with HR2 to form the critical 3:3 hexamer 6HB [

117]. The structural insights into RSV F have been pivotal in guiding structure-based peptide inhibitor design aimed at blocking 6HB formation [

61,

118,

119].

Early RSV heptad repeat (HR1/HR2) derived peptides were designed after the HIV paradigm but displayed only micromolar or sub-micromolar potency [

120,

121]. Among those, peptides derived from the HR2 region of RSV F (residues ~485–524) have been most extensively studied [

29,

32,

122]. One of the earliest, T-118 (

Figure 4) [

123], demonstrated inhibitory activity with an IC

50 of approximately 1500 nM in cytopathic effect assays and ~3500 nM in cell-fusion assays, indicating feasibility but limited potency [

32,

123,

124]. Subsequent structure-activity relationship studies revealed that both peptide length and sequence strongly affect potency. Longer peptides offered broader binding interfaces and improved stability. C20 (20 aa, residues 492–511) and C30 (30 aa, residues 482–511) peptides achieved IC

50 of 14.9 μM and 6.8 μM, respectively, in contrast to the lack of activity of C17 (17 aa, residues 495–511) at 100 μM. Further optimization led to the F478–516 peptide spanning the broader portion of the HR2 domain, which exhibited activity in the low micromolar range, i.e., ~1–10 μM, [

122,

125].

To enhance stability and binding affinity, several engineered poly-peptides containing alternating HR1 and HR2 sequences were developed, including 5-Helix, HR121, and HR212 constructs [

126,

127,

128]. These multimeric designs improve both structural integrity and inhibitory activity. For example, the 5-Helix construct consisting of three HR1 helices (N57) and two HR2 helices (C49) alternately linked by flexible peptide linkers achieved an IC

50 of 3.36 ± 0.23 μM, compared with 3.74 ± 0.67 μM and 7.95 ± 1.01 μM for HR121 and HR212, respectively [

32,

126]. Despite structural superiorities, the IC

50 values of these first-generation multimeric RSV constructs (~3–8 µM) did not drastically exceed F478–516, likely due to steric bulk hindering access to the crowded fusion site or non-optimized interface contacts in the chimera. However, they represent a more robust structural scaffold for further optimization than linear peptides.

A major advancement came with hydrocarbon-stapled peptides (

Figure 4), which stabilize α-helical conformations by covalently linking side chains to generate “staples.” These modifications substantially improve helicity, proteolytic resistance, and cellular uptake [

126,

129,

130]. Single-stapled constructs provided limited inhibition; however, double-stapled variants exhibited nanomolar activity in HEp-2 cells [

89,

130,

131]. Among these, the stabilized α-helix of the RSV F peptide, SAH-RSVF

BD (

Figure 4), is the best-characterized one [

131]. This 35-residue double-stapled peptide derived from RSV HR2 displayed markedly enhanced structural stability and antiviral potency compared to its unmodified counterpart, validating the stapling approach for Class I fusion systems [

131]. Gaillard and colleagues (2017) further introduced the “peptide 4 series”, a group of short (20-mer) double-stapled constructs with tighter staple spacing. Variants such as peptide 4ca exhibited remarkable potency, achieving superior antiviral activity and greater resistance to proteolytic degradation compared with longer stapled peptides. Intranasal administration of peptide 4ca substantially reduced RSV replication in the upper and lower respiratory tracts of mice, establishing proof of concept for clinical translation [

131,

132].

Persistent viral evolution has also driven resistance-driven innovation. Common escape variants such as K394R and D489Y prompted the design of novel candidates like CL-A3–7, which targets the F-IGF1R interface rather than the internal fusion machinery [

133]. This structure-based redirection of focus toward receptor-associated interactions offers a promising route to overcoming traditional resistance mechanisms.

The success of these engineered RSV F inhibitors, along with the previously discussed HIV-1 gp41 examples, highlights the versatility of structure-guided peptide design strategies, which have since been extended to other Class I fusion systems, such as the SARS-CoV-2 S2 protein discussed next.

Altogether, advances in peptide design targeting RSV F have followed a progressive refinement of structural and functional principles (

Table 2). T118 functions as a linear HR2-mimetic peptide that binds the HR1 region with moderate potency and stability. Interface optimization via sequence extension or multimeric scaffolds, enhanced HR1 engagement and neutralization potency, as seen in C30, F478–516, and 5-Helix peptides. SAH-RSVF

BD and 4ca incorporated hydrocarbon stapling to stabilize the α-helical conformation, preserving a pre-fusion-like structure and enhancing proteolytic resistance and binding affinity. These design strategies illustrate a rational trajectory from simple sequence mimicry to interface optimization, to structural stabilization, demonstrating a roadmap for improving potency, stability, and breadth in RSV F-targeted peptide therapeutics.

4.3. SARS-CoV-2 S Protein S2 Subunit

The spike protein (S, S1 + S2) of SARS-CoV-2 consists of two subunits, in which S2 drives membrane fusion after the S1 dissociates following ACE2 binding and proteolytic cleavage at the S2’ site [

134,

135]. Structural rearrangements in S2 include key steps, such as fusion peptide exposure, insertion into the host membrane to form putative pre-hairpin intermediates, and the folding of HR1 and HR2 back onto each other to form a 6HB [

4,

134]. The pre-hairpin intermediate is thought to adopt a configuration in which HR1 trimerizes and exposes hydrophobic grooves before HR2 folds back. This extended intermediate creates a therapeutic window for HR2-derived peptides to bind competitively and block fusion [

4,

134,

136].

Prior to the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, EK1 emerged as a pan-coronavirus inhibitor, rationally designed from HCoV-OC43 HR2, and demonstrated broader activity against SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV, etc. [

137]. When SARS-CoV-2 emerged, EK1 showed an IC

50 of 315 nM for cell–cell fusion assays and 2468 nM for virus infection [

137,

138]. IPB01, designed from the SARS-CoV-2 native HR2 sequence (residues 1168–1203,

Figure 4), potently inhibited cell–cell fusion (IC

50 = 22 nM) but displayed weak activity against pseudovirus and authentic viruses (IC

50 > 33 μM), which highlights the critical importance of membrane anchoring for effective viral entry inhibition [

137,

139].

Cholesterol conjugation, as a lipidation strategy, was then used to improve the antiviral activity of peptides. For example, the next generation EK1C4, in which EK1 was linked via PEG4 spacer to cholesterol, achieved a 242-fold increased potency for fusion (IC

50 = 1.3 nM vs. 315 nM) and 68-fold improvement against authentic virus (IC

50 = 36.5 nM vs. 2468 nM) [

140]. Structures of EK1 in complex with SARS-CoV-2 HR1 linked the better performance to key binding determinants, such as enhanced hydrophobic interactions (L10, F9, V7 replacing smaller residues in native HR2), optimized salt bridges (E21 to K25, K18), and critical pocket-binding residues (Y30) [

137]. Computational approaches identified specific mutations (EK1-8F, EK1-8Y, EK1-29A) that increase binding affinity by enhancing HR1 contacts and expanding the interface area [

141]. Another notable example is IPB02 (

Figure 4), the cholesterol-conjugated IPB01, which demonstrated IC

50 values of 25 nM for fusion and 80 nM for pseudovirus infection, showing improved efficacy compared to unconjugated IPB01 and exhibiting cross-inhibitory activity against HIV-1, HIV-2, and Simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) [

139]. The lipidation strategy pioneered by EK1C4 and IPB02 directly informed IPB29 (

Figure 4), which is now in Phase III clinical trials in China. IPB29 incorporates an EAAAK rigid linker between the HR2 peptide and cholesterol moiety, further enhancing α-helical stability and binding affinity [

142,

143].

[SARS

HRC-PEG

4]

2-Chol, a dimeric lipopeptide with two HR2-derived chains linked to a single cholesterol anchor, achieved IC

90 ~35 nM with biodistribution studies showing prolonged lung tissue retention compared to monomeric peptides [

144,

145]. In addition, the stapled approach was also applied, exemplified by the M2PA peptide, a short, double-hydrocarbon-stapled α-helical peptide derived from the HR2 region [

146].

Lipopeptides and stapled peptides were further optimized after more confined S2 elements were identified. Structural analysis showed that HR2 can extend beyond the traditional core, with N-terminal residues 1159–1179 forming structured motifs making extensive contact with HR1 grooves [

46,

144,

146,

147,

148]. This insight prompted the design of P42 (spanning residues 1162–1207) with six additional N-terminal residues, which exhibited an IC

50 of ~5 nM [

148]. Its derivative, P40-LP, containing four extended N-terminal residues (VDLG) plus cholesterol conjugation, demonstrated potent broad-spectrum activity against SARS-CoV-2 variants, including all Omicron sublineages and other human coronaviruses. P40-LP showed synergistic effects when combined with IPB24 (a C-terminal extended peptide), suggesting that peptides targeting distinct HR1 groove regions can cooperatively enhance inhibition [

147]. Later, combinatorial strategies like stapled lipopeptides incorporating hydrocarbon crosslinks to rigidify HR2 helices combined with cholesterol anchoring, led to the development of RQ-01, which achieved IC

50 of 3.4–8.9 nM against Omicron variants and was progressed to Phase II clinical trials [

149,

150]. To address peptide degradation limitations while maintaining HR1-binding pharmacophores, peptidomimetics like XY4-C7, a sulfonyl-γ-AApeptide-PEG24-Chol, using an unnatural backbone to mimic HR2, demonstrated potent in vitro and in vivo activity with protease resistance [

151]. These advanced design strategies have been integrated into clinical candidates like YKYY017, which progressed to Phase II trials in 2025 [

152]. Unlike the HR2-derived inhibitors, a 19-mer derived from the internal fusion peptide region, PN19, exhibited potent inhibitory activity against SARS-CoV-2 variants with no cytotoxicity [

153].

All the above examples illustrate the key design rules (

Table 3) that relate to generic strategies, such as EK1 (HR2 sequences from HCoV-OC43, MERS-CoV, and SARS-CoV-2) that emerged as a pan-coronavirus fusion inhibitor, to competitively bind HR1 and block 6HB formation. Derivatives such as EK1C4 and IPB02 incorporated cholesterol conjugation via PEG

4 spacers, anchoring peptides to fusion-active membranes, and achieved dramatic potency gains 68–242-fold. Structural optimization, including hydrophobic substitutions (L10, F9, V7), salt bridges (E21-K25, K18), and critical pocket-binding residues (Y30), enhanced HR1 interactions, while computationally guided mutations (EK1-8F, EK1-8Y, EK1-29A) further improved potency. IPB29, advancing to Phase III trials, introduced an EAAAK rigid linker for α-helical stabilization and membrane anchoring, complemented by dimerization ([SARSHRC-PEG

4]

2-Chol) and N-terminal sequence extensions (P42, P40-LP) to exploit expanded HR1 grooves. More recently, stapled lipopeptides combining hydrocarbon crosslinking with cholesterol anchoring (RQ-01) achieved low-nanomolar activity against Omicron variants and progressed to Phase II trials. Collectively, these strategies illustrate a progressive, structure-guided design trajectory from HR2 mimicry to lipidation, helical stabilization, and interface optimization, enabling potent, durable, and broadly active SARS-CoV-2 fusion inhibitors.

4.4. Human Influenza Virus Hemagglutinin HA

Influenza viruses are classified into four main types: A, B, C, and D, of which A, B, and C are known to cause illness in humans [

154]. The viral envelope contains two critical glycoproteins: hemagglutinin (HA) that mediates cell attachment and fusion, and neuraminidase (NA) that facilitates virion release. Influenza virus type A is further classified into subtypes based on HA (H1–H18) and NA combinations (N1–N11), of which, H1, H2, H5, H6, H8, H9, H11–H13, H16–H18 (phylogenetically similar stem epitope) were placed in group 1 and H3, H4, H7, H10, H14, H15 (phylogenetically distinct stem structure) were placed in group 2 [

4,

155]. The binding of the HA of the Influenza virus to the host cell via receptor (s) (sialic acid) mediates endocytosis, leading to the entry of the virus into the host cell. Later, fusion is triggered by low pH in endosomes, causing the fusion peptide containing hemagglutinin (HA2) to undergo conformational changes that drive fusion [

156,

157]. The structural complexity of HA, with its receptor-binding head domain and pH-dependent fusion mechanism, presents unique challenges for antiviral targeting. However, the HR2 is well-conserved, and stem regions also contain conserved epitopes recognized by broadly neutralizing antibodies [

158,

159], making them attractive targets for the design of peptide-based inhibitors.

Linear peptides derived from the HA2 fusion peptide or heptad repeat regions, however, exhibited weak micromolar potency, high proteolytic susceptibility, and poor pharmacokinetics [

26,

160]. To enhance membrane association and cellular uptake for endosomal targeting, cholesterol conjugation was applied to improve HA2-derived peptides, such as P155-185-chol (targeting H3N2,

Figure 4) [

56,

161,

162] and C20-Jp-Hp. C20-Jp-Hp is a hybrid peptide created by conjugating two short antiviral peptides, i.e., Jp and Hp with a C20 lipid chain [

160,

163,

164]. This peptide exhibited an IC

50 of 0.53 μM against H1N1 (A/Puerto Rico/8/34) with broad activity across H1N1, H3N2, drug-resistant NA-H274Y mutants, and influenza B viruses (IC

50 0.5–2.0 μM) [

163,

164]. To further improve the intracellular localization of the peptide, a cell-penetrating peptide sequence derived from HIV-1 TAT was combined with a lipid moiety (Cholesterol in Tat-HA2Ec2 in

Figure 4 and Tocopherol in Tat-HA2Ec3), which has been shown to enhance both in vitro and in vivo efficacy [

165].

High-resolution structures of antibody-complexed HA revealed that the conserved stem epitope is recognized primarily by the heavy chain complementarity-determining region 3 (HCDR3) loops and framework region 3 (FR3) residues [

166]. Kadam and his team then pioneered the design of cyclic peptides based on HCDR3 of FI6v3 and FR3 of CR9114, which led to the development of the P series (P2, P3, P4, P5, P6, and P7,

Figure 4) with approximately 100-fold affinity improvement through constraining the structure via rational cyclization and incorporating non-proteinogenic amino acids [

166,

167,

168]. Later, macrocyclic peptides with bifunctional inhibition (inhibiting both HA-mediated viral adsorption to cells and membrane fusion) were developed using the Random non-standard Peptides Integrated Discovery (RaPID) platform, resulting in the generation of iHA-100 (

Figure 4) with broad group 1 activity against H1N1, H5N1, H2N2, and H6N1 [

169].

Antibody hotspot mapping and computational docking against conserved epitopes of the HA stem further enabled the design of D-peptide inhibitors (mirror-image coordinates) to overcome protease resistance conferred by L-proteases [

170]. In contrast, the Frog defensin basic peptide (FBP) represents a nature-inspired optimization strategy derived from the naturally occurring frog defensin Urumin [

171]. Later, it was optimized through charge modification to broaden its antiviral spectrum against influenza A and B viruses by binding to HA and blocking the low-pH-induced conformational changes required for HA-mediated fusion in the endosome [

171,

172].

Key design rules from Influenza A anti-HA peptide inhibitors (

Table 4) include lipid conjugation (e.g., cholesterol in P155-185-chol and Tat-HA2Ec2/3 for endosomal targeting and improved pharmacokinetics), structural constraint via cyclization/stapling (e.g., P series yielding ~100-fold affinity gains against group 1 HA), and sequence optimization with non-natural amino acids (e.g., RaPID-derived iHA-100 for broad H1N1/H5N1 activity) which directly align with generic strategies like HR2 mimicry, chemical modifications for stability, and enhanced delivery. These optimizations translate micromolar limits of linear peptides into nanomolar potency across subtypes. These advancements exemplify broader structure-based principles for pan-influenza virus therapeutics targeting conserved HA fusion machinery.

4.5. Nipah Virus (NiV) F Protein

The fusion (F) protein of the Nipah virus (NiV) mediates viral and host cell membrane fusion through a mechanism characteristic of Class I viral fusion proteins, though with distinct molecular features. The F protein undergoes proteolytic activation in endosomes, exposing the hydrophobic fusion peptide for membrane insertion. Upon receptor binding by the attachment protein NiV-G to ephrinB2 or ephrinB3, conformational changes in NiV-F are triggered, leading to refolding of HR1 and HR2 into a stable 6HB that drives fusion of viral and host cell membranes [

4,

173]. Peptides, derived from the C-terminal heptad repeat (HR2) region of NiV F protein, mimic the HR regions and bind to HR1, therefore preventing the formation of the post-fusion conformation. The 42-mer peptide was designed based on the HR2 sequence (residues 447–489) [

174,

175]. Longer peptides like this, although having higher binding affinity, may suffer from poor solubility, low synthetic yield, and high toxicity. This peptide was thus further optimized into 36-mer versions with chemical modifications (e.g., capping, PEGylation and cholesterol conjugation). These modified peptides include capped NiV FC2 peptide (

Figure 4), N-PEG-NiV FC2 peptide, and C-PEG-NiV FC2 peptide, among which the N-PEG-NiV FC2 peptide was most potent [

174,

175] and V-Chol (

Figure 4) [

176].

N42NiV/HeV(L6)C32HPIV3 is a chimeric fusion core peptide construct designed to inhibit Nipah virus (NiV) and Hendra virus (HeV) fusion by targeting the HR1 (N42) region of NiV/HeV and the HR2 (C32) region of human parainfluenza virus 3 (HPIV3) joined by a short linker (L6). The high-resolution structure of this peptide revealed the molecular determinants underlying heterotypic peptide superiority. Enhanced binding was attributed to optimized interhelical packing and hydrophobic interactions within key groove regions [

176]. Guided by these insights, the HPIV3 HR2 peptide was engineered with the following specific substitutions: Glu459 to Valine, Ala463 to isoleucine, Gln479 to lysine, and Lys480 to isoleucine, and conjugated to lipid moieties, resulting in VIKI-dPEG4-chol and VIKI-dPEG4-bisToco (

Figure 4) [

177]. These modifications yielded potent inhibitors with an IC

50 of approximately 1–7 nM [

176] likely reflecting synergistic effects from both the sequence optimization and the membrane-targeting effect of cholesterol conjugation [

178].

More recently, stapled lipopeptides have shown even greater potential, exhibiting nanomolar-range inhibition against RSV, Ebola virus, and NiV. These peptides display enhanced protease stability and cellular permeability. Preliminary clinical studies of stapled lipopeptides (RQ-01,

Figure 4) targeting SARS-CoV-2 support their feasibility as broad-spectrum antivirals with potential applicability to NiV and other highly pathogenic viruses [

150].

Notable design rules for NiV F protein peptide inhibitors (

Table 5) align with generic solubilization strategies. Common strategies include shortening long HR2 peptides (e.g., 42-mer to 36-mer) and applying modifications such as N-terminal PEGylation (e.g., N-PEG-NiV FC2) or capping to enhance synthetic yield, solubility, and reduce toxicity while retaining HR1 binding affinity. The use of structure-guided heterotypic optimization, such as chimeric constructs (e.g., N42NiV/HeV(L6)C32HPIV3) or targeted substitutions in HPIV3 HR2 (Glu459Val, Ala463Ile, Gln479Lys, Lys480Ile for VIKI peptides), effectively improves interhelical packing and hydrophobic interactions, exemplifying chimeric sequence engineering. Integrating lipidation (e.g., cholesterol via PEG linkers in VIKI-dPEG4-chol) with stabilization (e.g., hydrocarbon stapling in RQ-01 lipopeptides) can boost membrane targeting, protease resistance, permeability, and broad-spectrum nanomolar potency.

4.6. Ebola Virus (EBOV) GP

The fusion of the Ebola virus (EBOV) with host cells is mediated by its envelope glycoprotein (GP), which consists of two subunits: GP1 and GP2 [

179,

180]. Among these, GP2 serves as a key target for peptide-based inhibitor design [

34,

180,

181]. Structural rearrangements within GP during the fusion process form the foundation for rational inhibitor development. After endocytosis, the GP1 subunit undergoes proteolytic cleavage by cathepsins within acidic endosomes, thereby exposing the Niemann-Pick C1 (NPC1) receptor-binding site [

182,

183]. Binding of NPC1 to cleaved GP1 triggers conformational changes in the GP2 subunit, which contains an internal fusion loop that inserts into the host endosomal membrane [

183]. GP2 subsequently refolds its heptad repeats into the 6HB, bringing the viral and endosomal membranes into close apposition to facilitate membrane fusion and release of the viral genome into the cytoplasm [

179,

182]. The transmembrane domain and fusion loop cooperate to open a fusion pore, completing the fusion process inside the late endosome [

4,

183,

184,

185].

Because EBOV fusion occurs in late endosomal compartments, a less accessible target site compared to HIV-1, it poses additional challenges for peptide targeting. Nevertheless, peptides directed against HR2 such as EBOV GP610 (

Figure 4) [

186], have demonstrated inhibition of EBOV pseudovirus infection [

181,

186]. Endosomal targeting has been achieved by conjugating the HR2 EBOV peptide to either the arginine-rich segment of the HIV-1 Tat protein, known for its endosomal localization, i.e., Tat Ebo (

Figure 4) [

181], or to a cholesterol group, i.e., Peptide 1-Chol (

Figure 4) [

187,

188]. Using a multilayered engineering strategy, Pessi et al. designed a 30-mer peptide that integrates multiple optimization strategies, including cholesterol conjugation (via cysteine residues at C-terminus), PEGylation (PEG12 as spacer), helix stapling through Lys(i)–Asp(i + 4) lactam bridges, and sequence extensions at both termini [

189]. Among the peptides generated, EBOV7 (

Figure 4) showed the greatest potency, with an IC

50 of 0.5 µM, and demonstrated 100% survival in mouse models when administered subcutaneously for 9 days [

189].

Inspired by successful HIV-1 HR1 engineering, additional efforts led to the development of eboIZN39IQ, a chimeric peptide that embeds coiled-coil modules (IZ and IQ) at the C-terminus of the natural EBOV HR1 sequence. Binding analysis demonstrated a Kd of 14 nM for eboIZN39IQ and its target GP2, comparable to the binding affinities observed for HIV-1 HR1-peptides and their cognate targets [

149,

190].

Collectively, design rules for EBOV GP2-targeted peptide inhibitors (

Table 6) emphasize multivalent modifications for endosomal access, such as cholesterol conjugation via C-terminal cysteine with PEG12 spacers in EBOV7, which overcomes late endosome barriers to achieve 0.5 µM IC

50 and full mouse survival, demonstrating lipidation for membrane anchoring and intracellular delivery beyond HIV-1 surface fusion. Helical stabilization through lactam bridges (Lys(i)–Asp(i + 4)) in EBOV7 enforces α-helical HR2 conformation to trap GP2 prehairpin intermediates, while eboIZN39IQ’s chimeric fusion of natural HR1 to IZ/IQ coiled-coil modules yields 14 nM Kd via stable N-trimer mimicry, linking directly to stapling and macrocyclization for enhanced coiled-coil affinity. Layered engineering in EBOV7 integrates lipidation, PEGylation, stapling, and N/C-terminal extensions into a potent 30-mer, mirroring HIV-1 HR1 strategies for orthogonal optimizations that boost broad-spectrum filovirus inhibition.