Seroprevalence of Dengue, Chikungunya, and Zika Viruses Among Febrile Patients in Dhaka, Bangladesh: A Hospital-Based Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

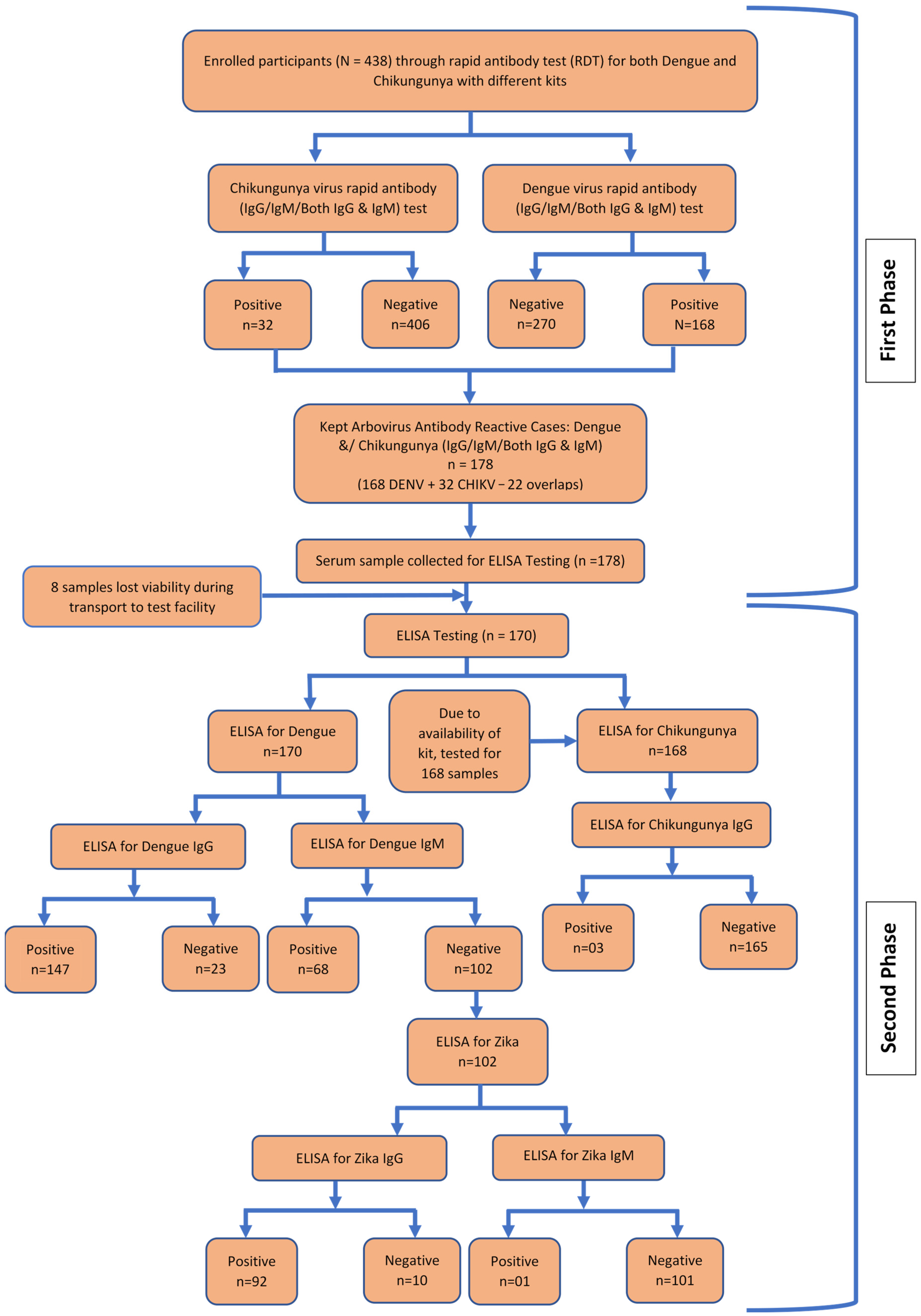

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Study Population

2.3. Study Setting

- Shaheed Suhrawardy Medical College Hospital

- DNCC Dedicated COVID-19 Hospital

- Kurmitola General Hospital

- Kuwait Bangladesh Friendship Government Hospital

2.4. Sample Size

2.5. Data and Sample Collection

2.6. Study Definitions

2.7. Variables

2.8. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic Descriptions of Participants

3.2. General Awareness About Aedes Mosquitoes and the Surrounding Physical Environment of the Participants, Protective Measures, Disease History, Symptoms, and Health Information Sources

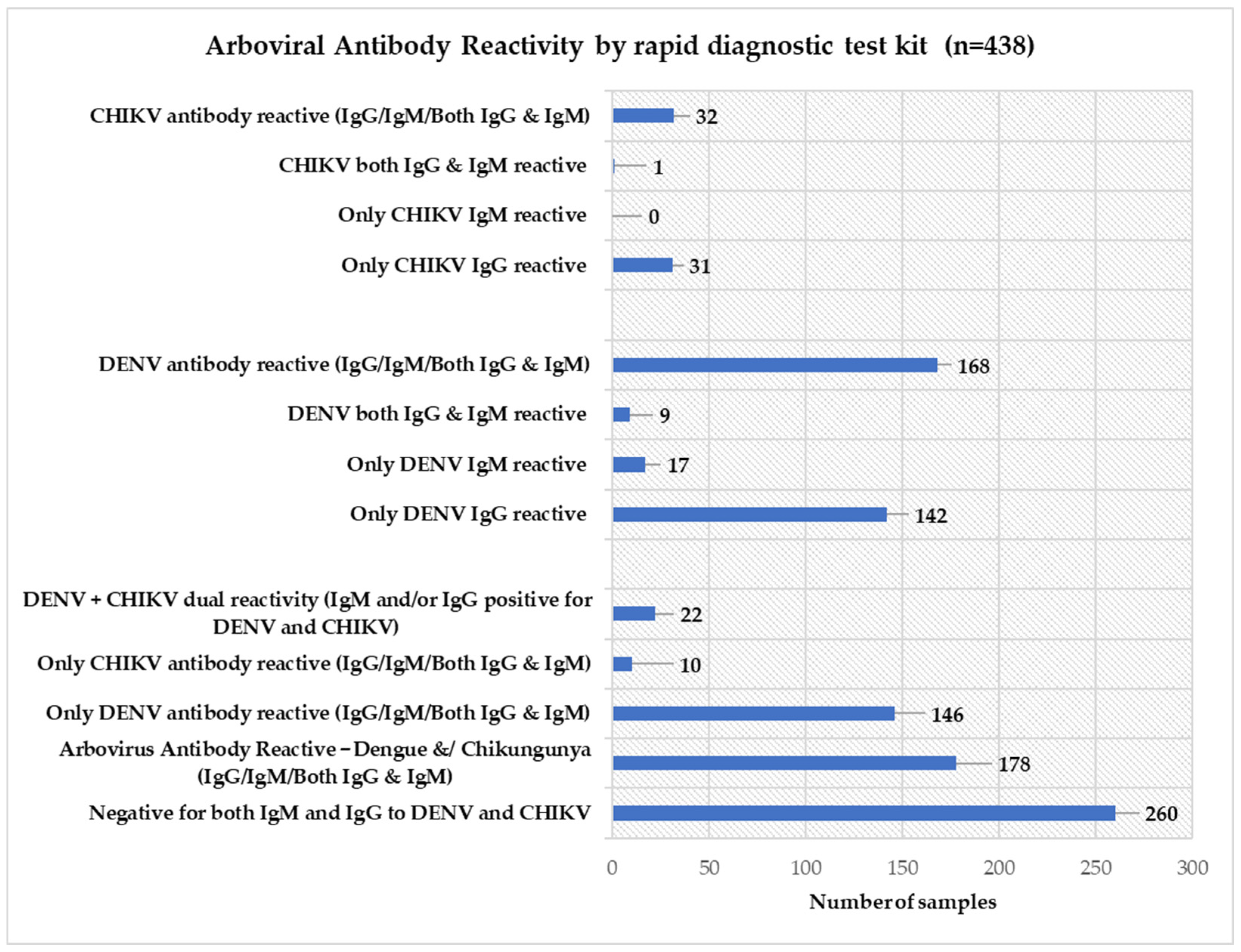

3.3. Arbovirus Antibody Reactivity

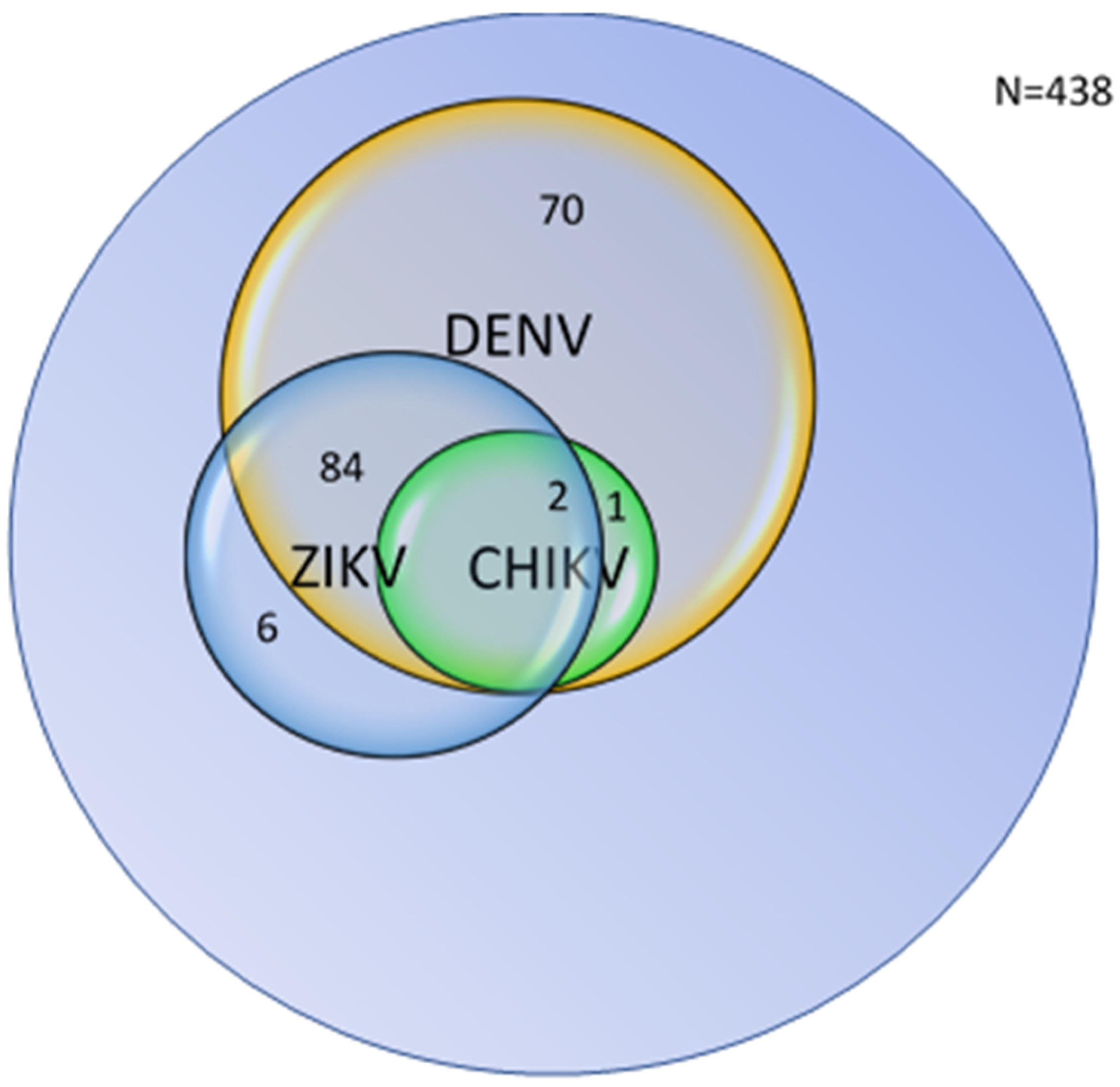

3.4. Combined Distribution and Overlap of Arboviral Seropositivity

3.5. Exploratory Associations Between Sociodemographic and Environmental Factors with Arbovirus Seropositivity by ELISA

3.5.1. DENV IgG Antibody Reactivity

3.5.2. DENV IgM Antibody Reactivity

3.5.3. ZIKV IgG Antibody Reactivity

3.5.4. ZIKV IgM and CHIKV IgG Antibody Reactivity

3.5.5. Overall Arboviral Antibody Reactivity

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ELISA | Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay |

| CHIKV | Chikungunya virus |

| DENV | Dengue virus |

| ZIKV | Zika virus |

| PRNT | Plaque reduction neutralization test |

| RDT | Rapid diagnostic test |

References

- Ahebwa, A.; Hii, J.; Neoh, K.B.; Chareonviriyaphap, T. Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus (Diptera: Culicidae) ecology, biology, behaviour, and implications on arbovirus transmission in Thailand: Review. One Health 2023, 16, 100555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kraemer, M.U.; Sinka, M.E.; Duda, K.A.; Mylne, A.Q.; Shearer, F.M.; Barker, C.M.; Moore, C.G.; Carvalho, R.G.; Coelho, G.E.; Van Bortel, W.; et al. The global distribution of the arbovirus vectors Aedes aegypti and Ae. albopictus. eLife 2015, 4, e08347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [Atlanta: CDC]. Zika Virus Zika Virus. 2025. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/zika/index.html (accessed on 7 September 2025).

- Bhatt, S.; Gething, P.W.; Brady, O.J.; Messina, J.P.; Farlow, A.W.; Moyes, C.L.; Drake, J.M.; Brownstein, J.S.; Hoen, A.G.; Sankoh, O.; et al. The global distribution and burden of dengue. Nature 2013, 496, 504–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gubler, D.J. Dengue and dengue hemorrhagic fever. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 1998, 11, 480–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization [WHO]. Dengue: Guidelines for Diagnosis, Treatment, Prevention and Control New Edition; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241547871 (accessed on 7 September 2025).

- Zeller, H.; Van Bortel, W.; Sudre, B. Chikungunya: Its history in Africa and Asia and its spread to new regions in 2013–2014. J. Infect. Dis. 2016, 214, S436–S440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charrel, R.N.; De Lamballerie, X.; Raoult, D. Chikungunya outbreaks—The globalization of vectorborne diseases. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007, 356, 769–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staples, J.E.; Fischer, M. Chikungunya virus in the Americas—What a vectorborne pathogen can do. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 371, 887–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dick, G.W.A.; Kitchen, S.F.; Haddow, A.J. Zika Virus (I). Isolations and serological specificity. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1952, 46, 509–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacNamara, F.N. Zika virus: A report on three cases of human infection during an epidemic of jaundice in Nigeria. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1954, 48, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faria, N.R.; Quick, J.; Claro, I.M.; Thézé, J.; De Jesus, J.G.; Giovanetti, M.; Kraemer, M.U.G.; Hill, S.C.; Black, A.; Da Costa, A.C.; et al. Establishment and cryptic transmission of Zika virus in Brazil and the Americas. Nature 2017, 546, 406–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chibueze, E.C.; Tirado, V.; Da Silva Lopes, K.; Balogun, O.O.; Takemoto, Y.; Swa, T.; Dagvadorj, A.; Nagata, C.; Morisaki, N.; Menendez, C.; et al. Zika virus infection in pregnancy: A systematic review of disease course and complications. Reprod. Health 2017, 14, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malik, M.R.; Walaskar, S.; Majji, R.; Sp, D.; Uppoor, S.; Kv, T.C.; Madhusudhan, H.N.; Balasundar, A.S.; Mishra, R.K.; Ishtiaq, F. Development of an affordable multiplex quantitative RT-PCR assay for early detection and surveillance of Dengue, Chikungunya, and co-infections from clinical samples in resource-limited settings. PLoS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2025, 19, e0013250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindholm, D.A.; Myers, T.; Widjaja, S.; Grant, E.M.; Telu, K.; Lalani, T.; Fraser, J.; Fairchok, M.; Ganesan, A.; Johnson, M.D.; et al. Mosquito exposure and chikungunya and dengue infection among travelers during the chikungunya outbreak in the Americas. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2017, 96, 903–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flamand, C.; Fritzell, C.; Matheus, S.; Dueymes, M.; Carles, G.; Favre, A.; Enfissi, A.; Adde, A.; Demar, M.; Kazanji, M.; et al. The proportion of asymptomatic infections and spectrum of disease among pregnant women infected by Zika virus: Systematic monitoring in French Guiana, 2016. Eurosurveillance 2017, 22, 17-00102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaboré, D.P.A.; Exbrayat, A.; Charriat, F.; Soma, D.D.; Sawadogo, S.P.; Ouédraogo, G.A.; Tuaillon, E.; Van de Perre, P.; Baldet, T.; Morel, C.; et al. A metagenomics survey of viral diversity in mosquito vectors allows the first detection of Sindbis virus in Burkina Faso. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0323767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.S.; Noman, A.A.; Mamun, S.A.A.; Mosabbir, A.A. Twenty-two years of dengue outbreaks in Bangladesh: Epidemiology, clinical spectrum, serotypes, and future disease risks. Trop. Med. Health 2023, 51, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization [WHO]. Dengue—Bangladesh Disease Outbreak News. 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2023-DON481 (accessed on 7 September 2025).

- Hossain, M.S.; Siddiqee, M.H.; Siddiqi, U.R.; Raheem, E.; Akter, R.; Hu, W. Dengue in a crowded megacity: Lessons learnt from 2019 outbreak in Dhaka, Bangladesh. PLoS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2020, 14, e0008349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M.; Sayed, S.J.B.; Moniruzzaman, M.; Humayon Kabir, A.K.M.; Mallik, M.d.U.; Hasan, M.d.R.; Siddique, A.B.; Hossain, A.; Uddin, N.; Hassan, M.; et al. Clinical and laboratory characteristics of an acute chikungunya outbreak in Bangladesh in 2017. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2018, 100, 405–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muraduzzaman, A.K.M.; Sultana, S.; Shirin, T.; Khatun, S.; Islam, M.; Rahman, M. Introduction of Zika virus in Bangladesh: An impending public health threat. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Med. 2017, 10, 925–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, I.; Dhimal, M.; Müller, R.; Banik, S.; Haque, U. The 2017 Dhaka chikungunya outbreak. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2017, 17, 1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasan, A.; Hossain, M.d.M.; Zamil, M.F.; Trina, A.T.; Hossain, M.S.; Kumkum, A.; Afreen, S.; Ahmed, D.; Rahman, M.; Alam, M.S. Concurrent transmission of Zika virus during the 2023 dengue outbreak in Dhaka, Bangladesh. PLoS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2025, 19, e0012866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vircell, S.L. Dengue ELISA IgG/IgM Capture: Instructions for Use, 7th ed.; Vircell, S.L., Ed.; Vircell: Granada, Spain, 2010; Available online: https://www.biosolutions.gr/images/stories/docs/DENGUE_ELISA_IgG_IgM_CAPTURE.pdf (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- Virion/ANVISA. ZIKA ELISA IgG Rev.00; Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária: Brasília, Brazil, 2019. Available online: https://consultas.anvisa.gov.br/api/consulta/produtos/25351605323201791/anexo/T13751290/nomeArquivo/ZIKA+ELISA+IgG+Rev.00+Virion.pdf (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- MyBioSource. Chikungunya Virus IgG (CHIKV IgG) ELISA Kit; MyBioSource: San Diego, CA, USA. 2025. Available online: https://www.mybiosource.com/human-elisa-kits/chikungunya-virus-igg-chikv-igg/1610578 (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Dhar-Chowdhury, P.; Paul, K.K.; Haque, C.E.; Hossain, S.; Lindsay, L.R.; Dibernardo, A.; Brooks, W.A.; Drebot, A.M. Dengue seroprevalence, seroconversion and risk factors in Dhaka, Bangladesh. PLoS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2017, 11, e0005475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, S.M.M.H.; Rashid, M.A.; Trisha, S.Y.; Ibrahim, M.; Hossen, M.d.S. Dengue investigation research in Bangladesh: Insights from a scoping review. Health Sci. Rep. 2025, 8, e70568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, S.W.; Santos, G.R.D.; Paul, K.K.; Paul, R.; Rahman, M.Z.; Alam, M.S.; Rahman, M.; Al-Amin, H.M.; Vanhomwegen, J.; Weaver, S.C.; et al. Results of a nationally representative seroprevalence survey of chikungunya virus in Bangladesh. J. Infect. Dis. 2024, 230, e1031–e1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musso, D.; Gubler, D.J. Zika virus. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2016, 29, 487–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrova, K.; Mendoza, E.J.; Mueller, N.; Wood, H. A plaque reduction neutralization test for the detection of ZIKV-Specific antibodies. In Methods in Molecular Biology; Humana: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, S.J.; Nisalak, A.; Anderson, K.B.; Libraty, D.H.; Kalayanarooj, S.; Vaughn, D.W.; Putnak, R.; Gibbons, R.V.; Jarman, R.; Endy, T.P. Dengue Plaque Reduction Neutralization Test (PRNT) in primary and secondary dengue virus infections: How alterations in assay conditions impact performance. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2009, 81, 825–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azami, N.A.M.; Moi, M.L.; Takasaki, T. Neutralization assay for chikungunya virus infection: Plaque reduction neutralization test. Methods Mol. Biol. 2016, 1426, 273–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhanoa, A.; Hassan, S.S.; Jahan, N.K.; Reidpath, D.D.; Fatt, Q.K.; Ahmad, M.P.; Meng, C.Y.; Ming, L.W.; Zain, A.Z.; Phipps, M.E.; et al. Seroprevalence of dengue among healthy adults in a rural community in Southern Malaysia: A pilot study. Infect. Dis. Poverty 2018, 7, 50–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.; Nielsen, A.L. Trends in the patterns of IgM and IgG antibodies in febrile persons with suspected dengue in Barbados, an English-speaking Caribbean country, 2006–2013. J. Infect. Public Health 2015, 8, 583–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, F.; Ma, Y.; Qin, P.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, Z.; Wang, W.; Cheng, B. Temperature-Driven dengue transmission in a changing climate: Patterns, trends, and future projections. GeoHealth 2024, 8, e2024GH001059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shepard, D.S.; Undurraga, E.A.; Betancourt-Cravioto, M.; Guzmán, M.G.; Halstead, S.B.; Harris, E.; Mudin, R.N.; Murray, O.K.; Tapia-Conyer, R.; Gubler, D.J. Approaches to refining estimates of global burden and economics of dengue. PLoS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2014, 8, e3306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman, L.R.; Donegan, S.; McCall, P.J. Is dengue vector control deficient in effectiveness or evidence?: Systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2016, 10, e0004551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messina, J.P.; Brady, O.J.; Scott, T.W.; Zou, C.; Pigott, D.M.; Duda, K.A.; Bhatt, S.; Katzelnick, L.; Howes, R.E.; Battle, K.E.; et al. Global spread of dengue virus types: Mapping the 70 year history. Trends Microbiol. 2014, 22, 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yesmin, S.; Sarmin, S.; Ahammad, A.M.; Rafi, M.d.A.; Hasan, M.J. Epidemiological investigation of the 2019 dengue outbreak in Dhaka, Bangladesh. J. Trop. Med. 2023, 2023, 8898453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paixão, E.S.; Teixeira, M.G.; Rodrigues, L.C. Zika, chikungunya and dengue: The causes and threats of new and re-emerging arboviral diseases. BMJ Glob. Health 2017, 3, e000530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [Atlanta: CDC]. Life Cycle of Aedes Mosquitoes [Internet]. Mosquitoes. 2024. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/mosquitoes/about/life-cycle-of-aedes-mosquitoes.html (accessed on 7 September 2025).

- WHO Regional Office for South-East Asia. Comprehensive Guideline for Prevention and Control of Dengue and Dengue Haemorrhagic Fever. Revised and expanded edition. 2011. Available online: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/204894 (accessed on 7 September 2025).

- Alobuia, W.M.; Missikpode, C.; Aung, M.; Jolly, P.E. Knowledge, attitude, and practices regarding vector-borne diseases in Western Jamaica. Ann. Glob. Health 2016, 81, 654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhimal, M.; Aryal, K.K.; Dhimal, M.L.; Gautam, I.; Singh, S.P.; Bhusal, C.L.; Kuch, U. Knowledge, Attitude and Practice Regarding Dengue Fever among the Healthy Population of Highland and Lowland Communities in Central Nepal. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e102028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banik, R.; Islam, M.d.S.; Mubarak, M.; Rahman, M.; Gesesew, H.A.; Ward, P.R.; Sikder, T. Public knowledge, belief, and preventive practices regarding dengue: Findings from a community-based survey in rural Bangladesh. PLoS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2023, 17, e0011778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abir, T.; Ekwudu, O.; Kalimullah, N.A.; Yazdani, D.M.N.A.; Mamun, A.A.; Basak, P.; Osuagwu, U.L.; Permarupan, P.Y.; Milton, A.H.; Talukder, S.H.; et al. Dengue in Dhaka, Bangladesh: Hospital-based cross-sectional KAP assessment at Dhaka North and Dhaka South City Corporation area. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0249135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sociodemographic Description | |

|---|---|

| Age in years | 30 (±13.5) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 293 (66.9%) |

| Female | 145 (33.1%) |

| Marital Status | |

| Never married/Single | 180 (41.1%) |

| Currently Married | 239 (54.7%) |

| Formerly Married (Separated/Divorced/Widowed) | 18 (4.1%) |

| Educational Status | |

| No formal education/Primary incomplete | 125 (28.54%) |

| Primary complete | 120 (27.4%) |

| Secondary complete | 60 (13.7%) |

| Higher | 133 (30.36%) |

| Religion | |

| Muslim | 427 (97.49%) |

| Other | 11 (2.51%) |

| Occupation | |

| Employed | 253 (57.8%) |

| Housewife | 70 (16.0%) |

| Student | 95 (21.7%) |

| Retired and Unemployed | 20 (4.6%) |

| Crowding Index | |

| <2 | 137 (31.3%) |

| 2–3 | 203 (46.4%) |

| >3 | 98 (22.4%) |

| Family monthly income | |

| ≤30,000 | 304 (69.4) |

| 30,001–100,000 | 122 (27.4) |

| >100,000 | 8 (1.8) |

| Don’t want to answer | 4 (0.9) |

| Mean (±SD), n (%) |

| General Awareness, Protective Measures, and Disease History | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Mosquito Responsible for Dengue, Zika, Chikungunya | |

| Aedes aegypti | 178 (40.6%) |

| All kind | 3 (0.7%) |

| Don’t know | 257 (58.7%) |

| Aedes aegypti Mosquito biting time | |

| Sunrise/sunset | 43 (9.8%) |

| Daytime | 134 (30.6%) |

| Night | 113 (25.8%) |

| Afternoon | 25 (5.7%) |

| All the time | 43 (9.8%) |

| Don’t know | 80 (18.3%) |

| Usual breeding place of Aedes aegypti mosquito | |

| Clean water | 58 (13.2%) |

| Wastewater | 334 (76.3%) |

| Stagnant water | 1 (0.2%) |

| Any water | 1 (0.2%) |

| Dense vegetation | 1 (0.2%) |

| Moist Environment | 1 (0.2%) |

| Don’t know | 42 (9.6%) |

| Open drains nearby (n = 430) | 132 (30.7%) |

| Deep vegetation or park nearby (n = 434) | 94 (21.7%) |

| Garden in the house or neighbourhood | 118 (26.9%) |

| Sanitary latrine in household | 430 (98.2%) |

| Construction sites (buildings) nearby (n = 431) | 152 (35.3%) |

| Road or bridge construction or repair nearby (n = 433) | 104 (24.0%) |

| Number of construction sites nearby | |

| 0 | 244 (55.71%) |

| 1 | 110 (25.11%) |

| 2 | 44 (10.05%) |

| >2 | 40 (9.13%) |

| Presence of items nearby that are potential Aedes mosquito breeding places | 104 (23.7%) |

| Recent cleanliness or drainage work by authorities | 432 (98.6%) |

| Recent cleanliness (Multiple response) | |

| By fogging | 385 (87.9%) |

| By cleaning drains | 82 (18.7%) |

| By removing stagnant water | 39 (8.9%) |

| By waste management | 203 (46.3%) |

| Personal protective measure against mosquito bite (Multiple response) | |

| Mosquito net | 371 (84.7%) |

| Coil | 327 (74.7%) |

| Closing door and window | 88 (20.1%) |

| Spray | 55 (12.6%) |

| Cleanliness | 49 (11.2%) |

| Others (Repellent, Long cloth, Smoke, Fan, Mosquito bat) | 16 (3.6%) |

| Nothing | 5 (1.1%) |

| Travel outside Dhaka in the last 14 days | 53 (12.1%) |

| Past diagnosed history (Multiple Responses) | |

| Dengue | 25 (5.7%) |

| Chikungunya | 6 (1.4%) |

| Zika | 0 (0.0%) |

| No history | 409 (93.4%) |

| Present Symptoms (Multiple Responses) | |

| Fatigue | 420 (95.9%) |

| Headache | 382 (87.2%) |

| Fever | 380 (86.2%) |

| Arthralgia and myalgia | 333 (76.0%) |

| Nausea | 240 (54.8%) |

| Conjunctivitis | 74 (16.9%) |

| Rash | 11 (2.5%) |

| Edema | 4 (0.9%) |

| Source of health education and information (Multiple Responses) | |

| Health Worker | 184 (42%) |

| Government campaign | 109 (24.9%) |

| Educational institute | 75 (17.1%) |

| Media | 291 (66.4%) |

| Family and friends | 318 (72.6%) |

| Virus | Antibody Type | Tested (n) | Positive Reactivity (n) | Positive Reactivity % Among Total Samples (n = 438) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dengue | IgG | 170 | 147 | 33.6% |

| IgM | 170 | 68 | 15.5% | |

| Zika | IgG | 102 | 92 | 21.0% |

| IgM | 102 | 1 | 0.2% | |

| Chikungunya | IgG | 168 | 3 | 0.7% |

| Serological Category | Definition | n | % of Total Study Population |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-reactive for all viruses | Non-reactive for both IgM and IgG to DENV, CHIKV, and ZIKV | 275 | 62.8% |

| Reactive for DENV only | IgM and/or IgG reactive for DENV; non-reactive for CHIKV and ZIKV | 70 | 15.9% |

| Reactive for CHIKV only | IgG reactive for CHIKV; non-reactive for DENV and ZIKV | 0 * | 0.0% |

| Reactive for ZIKV only | IgM and/or IgG reactive for ZIKV; non-reactive for DENV and CHIKV | 6 | 1.4% |

| Reactive for DENV + ZIKV | IgM and/or IgG reactive for both DENV and ZIKV; non-reactive for CHIKV | 84 | 19.2% |

| Reactive for DENV + CHIKV | IgM and/or IgG reactive for DENV and CHIKV; non-reactive for ZIKV | 1 | 0.2% |

| Reactive for ZIKV + CHIKV | IgM and/or IgG reactive for ZIKV and CHIKV; non-reactive for DENV | 0 | 0.0% |

| Reactive for Triple-virus | IgM and/or IgG reactive for DENV, CHIKV, and ZIKV | 2 | 0.5% |

| Total | 438 | 100% |

| Characteristic | N | Reactive N = 147 1 | Non-Reactive N = 291 1 | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years | 438 | 31.5 (±14.37) | 29.2 (±13.01) | 0.095 2 |

| Crowding in household | 438 | 2.8 (±2.01) | 2.5 (±1.77) | 0.213 2 |

| Sex | 438 | 0.886 3 | ||

| Male | 99 (67.35%) | 194 (66.67%) | ||

| Female | 48 (32.65%) | 97 (33.33%) | ||

| Education | 438 | 0.051 3 | ||

| No formal education | 16 (10.88%) | 36 (12.37%) | ||

| Primary incomplete | 33 (22.45%) | 40 (13.75%) | ||

| Primary complete | 45 (30.61%) | 75 (25.77%) | ||

| Secondary complete | 20 (13.61%) | 40 (13.75%) | ||

| Higher secondary complete | 14 (9.52%) | 32 (11.00%) | ||

| Graduation or above | 19 (12.93%) | 68 (23.37%) | ||

| Open drain in neighborhood | 430 | 42 (29.17%) | 90 (31.47%) | 0.625 3 |

| Deep vegetation or park in neighborhood | 434 | 30 (20.55%) | 64 (22.22%) | 0.689 3 |

| Garden in house or neighborhood | 438 | 39 (26.53%) | 79 (27.15%) | 0.891 3 |

| Building construction site nearby | 431 | 49 (34.03%) | 103 (35.89%) | 0.703 3 |

| Road, bridge construction nearby | 433 | 31 (21.53%) | 73 (25.26%) | 0.392 3 |

| Potential mosquito breeding place nearby | 438 | 38 (25.85%) | 66 (22.68%) | 0.462 3 |

| Recent cleanliness and drainage work (gov or others) | 438 | 145 (98.64%) | 287 (98.63%) | >0.999 4 |

| Personal protective measure against mosquito bite | ||||

| Spray | 438 | 23 (15.65%) | 32 (11.00%) | 0.166 3 |

| Coil | 438 | 107 (72.79%) | 220 (75.60%) | 0.523 3 |

| Repellent | 438 | 1 (0.68%) | 3 (1.03%) | >0.999 4 |

| Closing doors and windows | 438 | 26 (17.69%) | 62 (21.31%) | 0.372 3 |

| Cleanliness | 438 | 15 (10.20%) | 34 (11.68%) | 0.643 3 |

| Mosquito net | 438 | 124 (84.35%) | 247 (84.88%) | 0.885 3 |

| Long cloths | 438 | 1 (0.68%) | 1 (0.34%) | >0.999 4 |

| Nothing | 438 | 1 (0.68%) | 4 (1.37%) | 0.668 4 |

| Travel outside Dhaka | 438 | 17 (11.56%) | 36 (12.37%) | 0.807 3 |

| Characteristic | N | Reactive N = 68 1 | Non-Reactive N = 370 1 | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years | 438 | 28.5 (±12.37) | 30.3 (±13.70) | 0.331 2 |

| Crowding in household | 438 | 3.0 (±2.52) | 2.6 (±1.71) | 0.078 2 |

| Sex | 438 | 0.676 3 | ||

| Male | 44 (64.71%) | 249 (67.30%) | ||

| Female | 24 (35.29%) | 121 (32.70%) | ||

| Education | 438 | 0.022 3 | ||

| No formal education | 6 (8.82%) | 46 (12.43%) | ||

| Primary incomplete | 18 (26.47%) | 55 (14.86%) | ||

| Primary complete | 20 (29.41%) | 100 (27.03%) | ||

| Secondary complete | 9 (13.24%) | 51 (13.78%) | ||

| Higher secondary complete | 10 (14.71%) | 36 (9.73%) | ||

| Graduation or above | 5 (7.35%) | 82 (22.16%) | ||

| Open drain in neighborhood | 430 | 23 (34.33%) | 109 (30.03%) | 0.483 3 |

| Deep vegetation or park in neighborhood | 434 | 14 (20.59%) | 80 (21.86%) | 0.815 3 |

| Garden in house or neighborhood | 438 | 16 (23.53%) | 102 (27.57%) | 0.490 3 |

| Building construction site nearby | 431 | 27 (41.54%) | 125 (34.15%) | 0.251 3 |

| Road, bridge construction nearby | 433 | 15 (23.08%) | 89 (24.18%) | 0.847 3 |

| Potential mosquito breeding place nearby | 438 | 19 (27.94%) | 85 (22.97%) | 0.376 3 |

| Recent cleanliness and drainage work (gov or others) | 438 | 66 (97.06%) | 366 (98.92%) | 0.235 4 |

| Personal protective measure against mosquito bite | ||||

| Spray | 438 | 8 (11.76%) | 47 (12.70%) | 0.830 3 |

| Coil | 438 | 53 (77.94%) | 274 (74.05%) | 0.498 3 |

| Repellent | 438 | 0 (0.00%) | 4 (1.08%) | >0.999 4 |

| Closing doors and windows | 438 | 12 (17.65%) | 76 (20.54%) | 0.584 3 |

| Cleanliness | 438 | 7 (10.29%) | 42 (11.35%) | 0.799 3 |

| Mosquito net | 438 | 60 (88.24%) | 311 (84.05%) | 0.379 3 |

| Long cloths | 438 | 0 (0.00%) | 2 (0.54%) | >0.999 4 |

| Nothing | 438 | 0 (0.00%) | 5 (1.35%) | >0.999 4 |

| Travel outside Dhaka | 438 | 9 (13.24%) | 44 (11.89%) | 0.755 3 |

| Characteristic | N | Reactive N = 92 1 | Non-Reactive N = 346 1 | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years | 438 | 33.5 (±14.99) | 29.1 (±12.95) | 0.005 2 |

| Crowding in household | 438 | 2.6 (±1.39) | 2.6 (±1.96) | 0.678 2 |

| Sex | 438 | 0.909 3 | ||

| Male | 62 (67.39%) | 231 (66.76%) | ||

| Female | 30 (32.61%) | 115 (33.24%) | ||

| Education | 438 | 0.949 3 | ||

| No formal education | 11 (11.96%) | 41 (11.85%) | ||

| Primary incomplete | 15 (16.30%) | 58 (16.76%) | ||

| Primary complete | 29 (31.52%) | 91 (26.30%) | ||

| Secondary complete | 11 (11.96%) | 49 (14.16%) | ||

| Higher secondary complete | 9 (9.78%) | 37 (10.69%) | ||

| Graduation or above | 17 (18.48%) | 70 (20.23%) | ||

| Open drain in your area | 430 | 25 (27.78%) | 107 (31.47%) | 0.499 3 |

| Deep vegetation or park in neighborhood | 434 | 20 (21.98%) | 74 (21.57%) | 0.934 3 |

| Garden in house or neighborhood | 438 | 26 (28.26%) | 92 (26.59%) | 0.748 3 |

| Building construction site nearby | 431 | 26 (28.57%) | 126 (37.06%) | 0.132 3 |

| Road, bridge construction nearby | 433 | 20 (21.74%) | 84 (24.63%) | 0.564 3 |

| Potential mosquito breeding place nearby | 438 | 21 (22.83%) | 83 (23.99%) | 0.816 3 |

| Recent cleanliness and drainage work (gov or others) | 438 | 90 (97.83%) | 342 (98.84%) | 0.610 4 |

| Personal protective measure against mosquito bite | ||||

| Spray | 438 | 15 (16.30%) | 40 (11.56%) | 0.222 3 |

| Coil | 438 | 64 (69.57%) | 263 (76.01%) | 0.206 3 |

| Repellent | 438 | 2 (2.17%) | 2 (0.58%) | 0.196 4 |

| Closing doors and windows | 438 | 16 (17.39%) | 72 (20.81%) | 0.467 3 |

| Cleanliness | 438 | 11 (11.96%) | 38 (10.98%) | 0.792 3 |

| Mosquito net | 438 | 77 (83.70%) | 294 (84.97%) | 0.763 3 |

| Long cloths | 438 | 0 (0.00%) | 2 (0.58%) | >0.999 4 |

| Nothing | 438 | 1 (1.09%) | 4 (1.16%) | >0.999 4 |

| Travel outside Dhaka | 438 | 11 (11.96%) | 42 (12.14%) | 0.962 3 |

| Characteristic | N | Reactive N = 163 1 | Non-Reactive N = 275 1 | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years | 438 | 31.1 (±14.13) | 29.3 (±13.11) | 0.184 2 |

| Crowding in household | 438 | 2.7 (±1.94) | 2.6 (±1.81) | 0.371 2 |

| Sex | 438 | 0.827 3 | ||

| Male | 108 (66.26%) | 185 (67.27%) | ||

| Female | 55 (33.74%) | 90 (32.73%) | ||

| Education | 438 | 0.168 3 | ||

| No formal education | 17 (10.43%) | 35 (12.73%) | ||

| Primary incomplete | 33 (20.25%) | 40 (14.55%) | ||

| Primary complete | 49 (30.06%) | 71 (25.82%) | ||

| Secondary complete | 22 (13.50%) | 38 (13.82%) | ||

| Higher secondary complete | 19 (11.66%) | 27 (9.82%) | ||

| Graduation or above | 23 (14.11%) | 64 (23.27%) | ||

| Open drain in your area | 430 | 48 (30.00%) | 84 (31.11%) | 0.809 3 |

| Deep vegetation or park in neighborhood | 434 | 34 (20.99%) | 60 (22.06%) | 0.793 3 |

| Garden in house or neighborhood | 438 | 43 (26.38%) | 75 (27.27%) | 0.839 3 |

| Building construction site nearby | 431 | 54 (33.96%) | 98 (36.03%) | 0.665 3 |

| Road, bridge construction nearby | 433 | 36 (22.50%) | 68 (24.91%) | 0.571 3 |

| Potential mosquito breeding place nearby | 438 | 41 (25.15%) | 63 (22.91%) | 0.594 3 |

| Recent cleanliness and drainage work (gov or others) | 438 | 159 (97.55%) | 273 (99.27%) | 0.201 4 |

| Personal protective measure against mosquito bite | ||||

| Spray | 438 | 24 (14.72%) | 31 (11.27%) | 0.292 3 |

| Coil | 438 | 118 (72.39%) | 209 (76.00%) | 0.401 3 |

| Repellent | 438 | 2 (1.23%) | 2 (0.73%) | 0.631 4 |

| Closing doors and windows | 438 | 30 (18.40%) | 58 (21.09%) | 0.498 3 |

| Cleanliness | 438 | 18 (11.04%) | 31 (11.27%) | 0.941 3 |

| Mosquito net | 438 | 139 (85.28%) | 232 (84.36%) | 0.798 3 |

| Long cloths | 438 | 1 (0.61%) | 1 (0.36%) | >0.999 4 |

| Nothing | 438 | 1 (0.61%) | 4 (1.45%) | 0.655 4 |

| Travel outside Dhaka | 438 | 20 (12.27%) | 33 (12.00%) | 0.933 3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Dutta, A.; Sanin, K.I.; Sharaque, A.R.; Elahi, M.; Roy, B.R.; Hasan, M.K.; Rahman, M.S.; Ahamed, M.S.; Hossain, M.E.; Islam, M.S.; et al. Seroprevalence of Dengue, Chikungunya, and Zika Viruses Among Febrile Patients in Dhaka, Bangladesh: A Hospital-Based Cross-Sectional Study. Pathogens 2026, 15, 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens15010031

Dutta A, Sanin KI, Sharaque AR, Elahi M, Roy BR, Hasan MK, Rahman MS, Ahamed MS, Hossain ME, Islam MS, et al. Seroprevalence of Dengue, Chikungunya, and Zika Viruses Among Febrile Patients in Dhaka, Bangladesh: A Hospital-Based Cross-Sectional Study. Pathogens. 2026; 15(1):31. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens15010031

Chicago/Turabian StyleDutta, Abir, Kazi Istiaque Sanin, Azizur Rahman Sharaque, Mahbub Elahi, Bharati Rani Roy, Md. Khaledul Hasan, Md. Sajjadur Rahman, Md. Shakil Ahamed, Mohammad Enayet Hossain, Md. Shafiqul Islam, and et al. 2026. "Seroprevalence of Dengue, Chikungunya, and Zika Viruses Among Febrile Patients in Dhaka, Bangladesh: A Hospital-Based Cross-Sectional Study" Pathogens 15, no. 1: 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens15010031

APA StyleDutta, A., Sanin, K. I., Sharaque, A. R., Elahi, M., Roy, B. R., Hasan, M. K., Rahman, M. S., Ahamed, M. S., Hossain, M. E., Islam, M. S., Nadia, N., Dutta, G. K., Rahman, M. Z., Khan, M. N. A., Islam, M. N., & Tofail, F. (2026). Seroprevalence of Dengue, Chikungunya, and Zika Viruses Among Febrile Patients in Dhaka, Bangladesh: A Hospital-Based Cross-Sectional Study. Pathogens, 15(1), 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens15010031