Epidemiology of Herpes Simplex and Varicella Zoster Virus-Associated Central Nervous System Infections in Western Greece: A Five-Year Retrospective Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Acquisition-Characteristics of Population

2.2. Description of PCR

- HSV-1 (Herpes Simplex Virus Type 1): Detected by a specific probe targeting the gene encoding glycoprotein G.

- HSV-2 (Herpes Simplex Virus Type 2): Detected by a specific probe targeting the gene encoding glycoprotein D.

- VZV (Varicella Zoster Virus): Detected by specific probes targeting the UL21 and ORF62 genes.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. HSV-1, HSV-2 and VZV Positivity

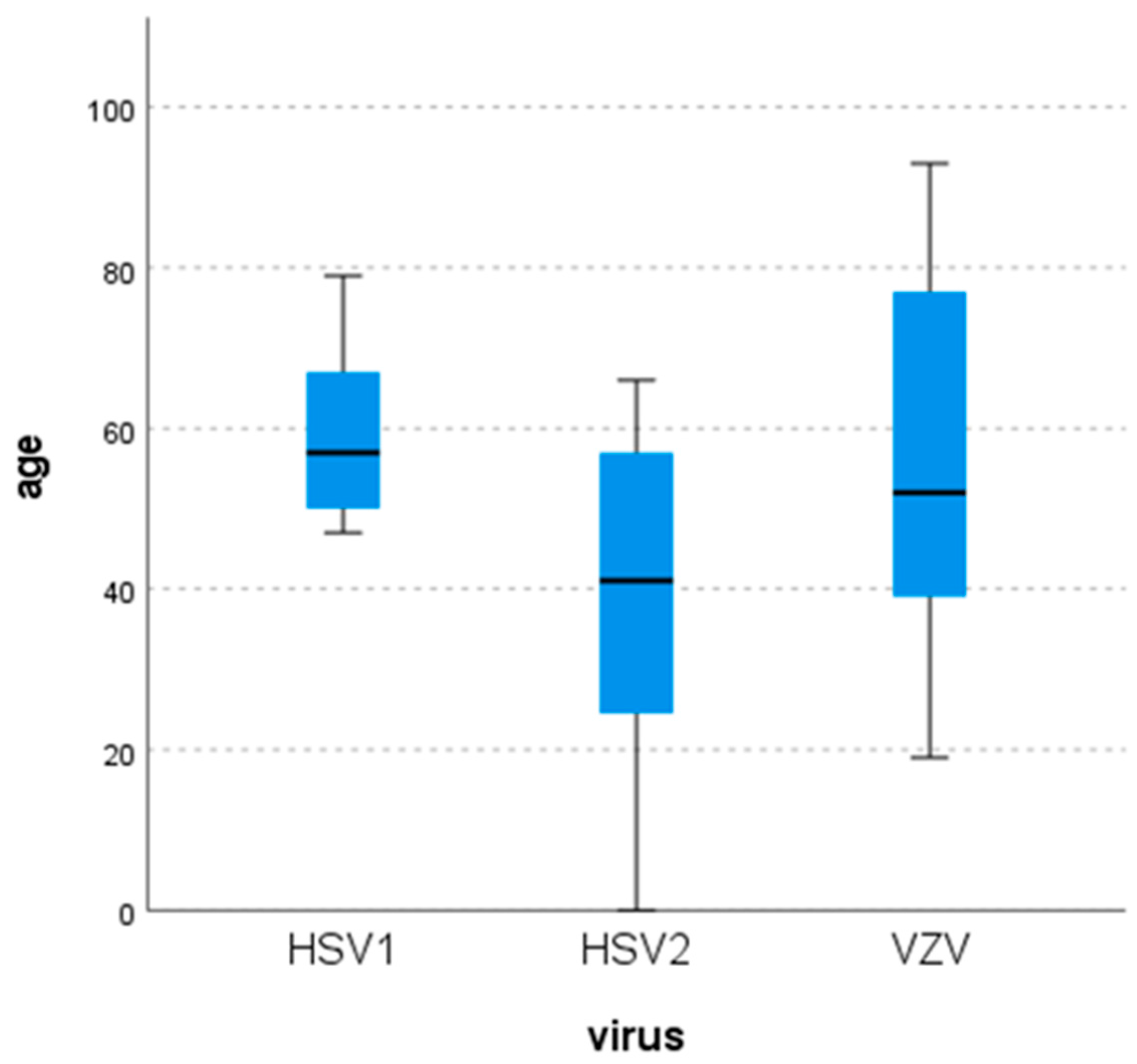

3.2. Demographic Characteristics of Patients Infected with HSV-1, HSV-2 or VZV

3.3. Seasonal Distribution

3.4. Clinical Findings

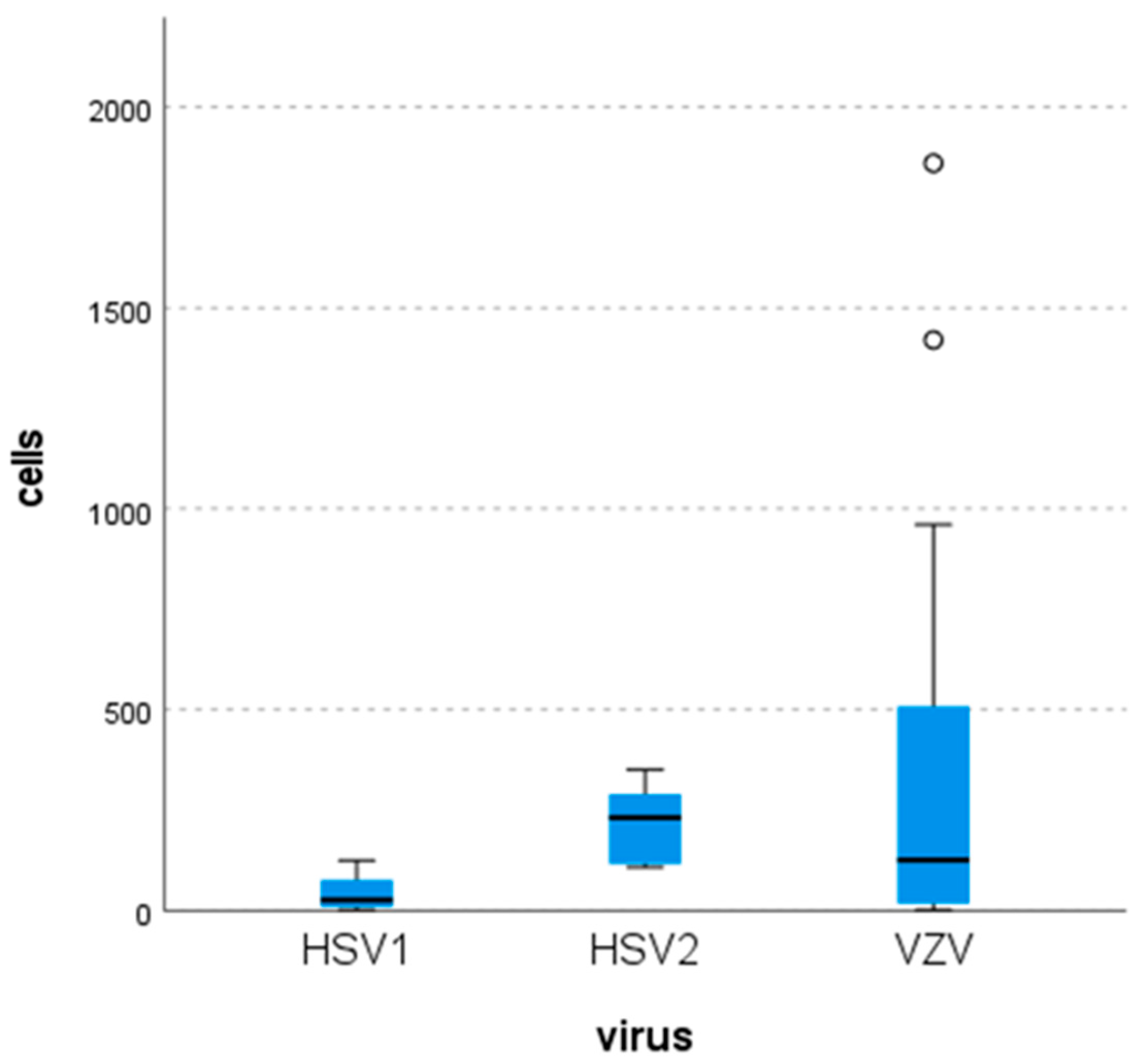

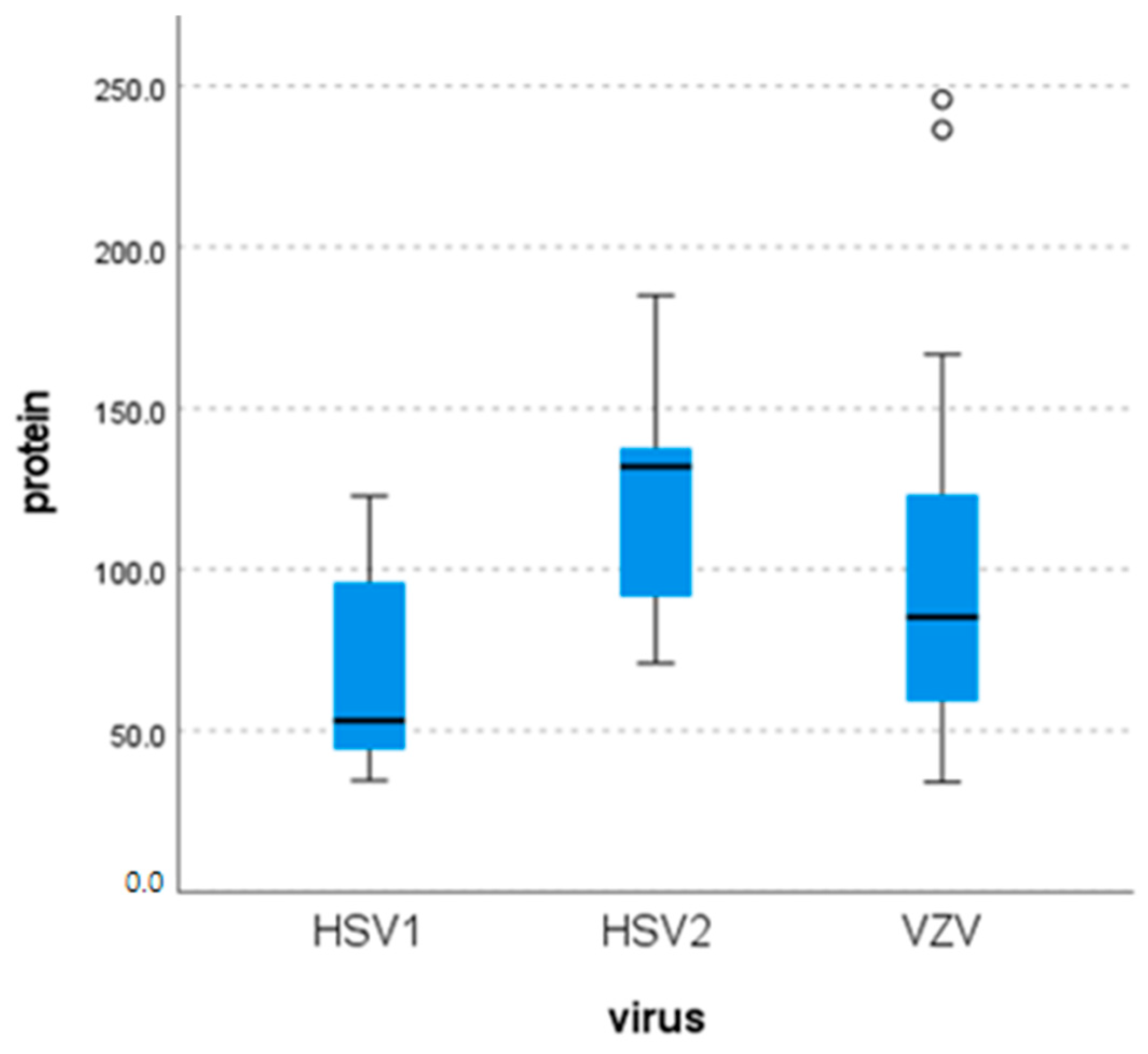

3.5. Laboratory Findings

3.6. Cranial Imaging

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AUTH | Aristotle University of Thessaloniki |

| CBC | Complete Blood Count |

| CLL | Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia |

| CMV | Cytomegalovirus |

| CNS | Central Nervous System |

| CRP | C-reactive Protein |

| CT | Computed Tomography |

| CSF | Cerebro-Spinal Fluid |

| HSV | Herpes Simplex Virus |

| IC | Internal Control |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| NGS | Next-Generation Sequencing |

| PCR | Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| SLE | Systemic Lupus Erythematosus |

| VZV | Varicella Zoster Virus |

| WBC | White Blood Cell |

References

- Steiner, I.; Kennedy, P.G.; Pachner, A.R. The neurotropic herpes viruses: Herpes simplex and varicella-zoster. Lancet Neurol. 2007, 6, 1015–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arruti, M.; Piñeiro, L.; Salicio, Y.; Cilla, G.; Goenaga, M.; de Munain, A.L. Incidence of varicella zoster virus infections of the central nervous system in the elderly: A large tertiary hospital-based series (2007–2014). J. NeuroVirol. 2017, 23, 451–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadambari, S.; Abdullahi, F.; Celma, C.; Ladhani, S. Epidemiological trends in viral meningitis in England: Prospective national surveillance, 2013–2023. J. Infect. 2024, 89, 106223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calleri, G.; Libanore, V.; Corcione, S.; De Rosa, F.G.; Caramello, P. A retrospective study of viral central nervous system infections: Relationship amongst aetiology, clinical course and outcome. Infection 2017, 45, 227–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jarrin, I.; Sellier, P.; Lopes, A.; Morgand, M.; Makovec, T.; Delcey, V.; Champion, K.; Simoneau, G.; Green, A.; Mouly, S.; et al. Etiologies and Management of Aseptic Meningitis in Patients Admitted to an Internal Medicine Department. Medicine 2016, 95, 2372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parkes-Smith, J.; Chaudhuri, A. Varicella Zoster Virus: An under-recognised cause of central nervous system infections? Intern. Med. J. 2020, 52, 100–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Abid, F.; Abukhattab, M.; Ghazouani, H.; Khalil, O.; Gohar, A.; Al Soub, H.; Al Maslamani, M.; Al Khal, A.; Al Masalamani, E.; Al Dhahry, S.; et al. Epidemiology and clinical outcomes of viral central nervous system infections. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2018, 73, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pormohammad, A.; Goudarzi, H.; Eslami, G.; Falah, F.; Taheri, F.; Ghadiri, N.; Faghihloo, E. Epidemiology of Herpes simplex and Varicella zoster virus in Cerebrospinal fluid of patients suffering from meningitis in Iran. New Microbes New Infect. 2020, 30, 100688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garber, B.; Glauser, J. Viral Meningitis and Encephalitis Update. Curr. Emerg. Hosp. Med. Rep. 2024, 12, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGill, F.; Griffiths, M.J.; Bonnett, L.J.; Geretti, A.M.; Michael, B.D.; Beeching, N.J.; McKee, D.; Scarlett, P.; Hart, I.J.; Mutton, K.J.; et al. Incidence, aetiology, and sequelae of viral meningitis in UK adults: A multicentre prospective observational cohort study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2018, 18, 992–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granerod, J.; Ambrose, H.E.; Davies, N.W.S.; Clewley, J.P.; Walsh, A.L.; Morgan, D.; Cunningham, R.; Zuckerman, M.; Mutton, K.J.; Solomon, T.; et al. Causes of encephalitis and differences in their clinical presentations in England: A multicentre, population-based prospective study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2010, 10, 835–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradshaw, M.J.; Venkatesan, A. Herpes Simplex Virus-1 Encephalitis in Adults: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and Management. Neurotherapeutics 2016, 13, 493–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boucher, A.; Herrmann, J.; Morand, P.; Buzelé, R.; Crabol, Y.; Stahl, J.; Mailles, A. Epidemiology of infectious encephalitis causes in 2016. Méd. Mal. Infect. 2017, 47, 221–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldriweesh, M.A.; Shafaay, E.A.; Alwatban, S.M.; Alkethami, O.M.; Aljuraisi, F.N.; Bosaeed, M.; Alharbi, N.K. Viruses Causing Aseptic Meningitis: A Tertiary Medical Center Experience with a Multiplex PCR Assay. Front. Neurol. 2020, 11, 602267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pollak, L.; Dovrat, S.; Book, M.; Mendelson, E.; Weinberger, M. Varicella zoster vs. herpes simplex meningoencephalitis in the PCR era. A single center study. J. Neurol. Sci. 2012, 314, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, K.E.; Alexander, B.D.; Woods, C.; Petti, C.; Reller, L.B. Validation of Laboratory Screening Criteria for Herpes Simplex Virus Testing of Cerebrospinal Fluid. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2007, 45, 721–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stahl, J.P.; Mailles, A. Update on HSV and VZV Encephalitis in Adults. In Current Clinical Neurology; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 153–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, E.; Beckham, J.D.; Piquet, A.L.; Tyler, K.L.; Chauhan, L.; Pastula, D.M. Herpesvirus-Associated Encephalitis: An Update. Curr. Trop. Med. Rep. 2022, 9, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaewpoowat, Q.; Salazar, L.; Aguilera, E.; Wootton, S.H.; Hasbun, R. Herpes simplex and varicella zoster CNS infections: Clinical presentations, treatments and outcomes. Infection 2015, 44, 337–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simko, J.P.; Caliendo, A.M.; Hogle, K.; Versalovic, J. Differences in Laboratory Findings for Cerebrospinal Fluid Specimens Obtained from Patients with Meningitis or Encephalitis Due to Herpes Simplex Virus (HSV) Documented by Detection of HSV DNA. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2002, 35, 414–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albert, E.; Alberola, J.; Bosque, M.; Camarena, J.J.; Clari, M.Á.; Márquez, M.V.D.; Gil-Fortuño, M.; Gimeno, A.; Nogueira, J.M.; Ocete, M.D.; et al. Missing Cases of Herpes Simplex Virus (HSV) Infection of the Central Nervous System When the Reller Criteria Are Applied for HSV PCR Testing: A Multicenter Study. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2019, 57, e01719-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López Roa, P.; Alonso, R.; de Egea, V.; Usubillaga, R.; Muñoz, P.; Bouza, E. PCR for Detection of Herpes Simplex Virus in Cerebrospinal Fluid: Alternative Acceptance Criteria for Diagnostic Workup. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2013, 51, 2880–2883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingues, R.B.; Lakeman, F.D.; Mayo, M.S.; Whitley, R.J. Application of Competitive PCR to Cerebrospinal Fluid Samples from Patients with Herpes Simplex Encephalitis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1998, 36, 2229–2234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeBiasi, R.L.; Tyler, K.L. Molecular Methods for Diagnosis of Viral Encephalitis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2004, 17, 903–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, G.-H.; Kim, J.; Kim, H.-W.; Cho, J.W. Herpes simplex viruses (1 and 2) and varicella-zoster virus infections in an adult population with aseptic meningitis or encephalitis. Medicine 2021, 100, e27856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvarez, J.C.; Ticono, J.; Medallo, P.; Miranda, H.; Ferrés, M.; Forero, J.; Álvarez, C. Varicella-Zoster Virus Meningitis and Encephalitis: An Understated Cause of Central Nervous System Infections. Cureus 2020, 12, 11583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishimaru, S.; Kawamura, Y.; Miura, H.; Shima, S.; Ueda, A.; Watanabe, H.; Mutoh, T.; Yoshikawa, T. Detection of human herpesviruses in cerebrospinal fluids collected from patients suspected of neuroinfectious diseases. J. NeuroVirol. 2021, 28, 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, C.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, H.; Zhang, Q.; Hu, H.; Song, Z.; Chen, R.; Liu, D. Comparisons in the changes of clinical characteristics and cerebrospinal fluid cytokine profiles between varicella-zoster virus meningitis/encephalitis and other central nervous system infections. Zhong Nan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban = J. Cent. South Univ. Med. Sci. 2022, 47, 1345–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahl, J.P. Update on HSV and VZV infections of the brain. Rev. Neurol. 2019, 175, 442–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shikova, E.; Kumanova, A.; Tournev, I.; Zhelyazkova, S.; Vassileva, E.; Ivanov, I.; Pishmisheva, M. Varicella zoster virus infection in neurological patients in Bulgaria. J. NeuroVirol. 2021, 27, 272–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puchhammer-Stöckl, E.; Aberle, S.W.; Heinzl, H. Association of age and gender with alphaherpesvirus infections of the central nervous system in the immunocompetent host. J. Clin. Virol. 2012, 53, 356–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohani, H.; Arjmand, R.; Mozhgani, S.-H.; Shafiee, A.; Amini, M.J.; Forghani-Ramandi, M.-M. The Worldwide Prevalence of Herpes Simplex Virus Encephalitis and Meningitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Turk. Arch. Pediatr. 2023, 58, 580–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papa, A.; Papadopoulou, E. Acute viral infections of the central nervous system, 2014–2016, Greece. J. Med. Virol. 2017, 90, 644–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tabaja, H.; Sharara, S.; Aad, Y.A.; Beydoun, N.; Tabbal, S.; Makki, A.; Mahfouz, R.; Kanj, S. Varicella zoster virus infection of the central nervous system in a tertiary care center in Lebanon. Méd. Mal. Infect. 2020, 50, 280–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HSV-1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 9 |

| HSV-2 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 7 |

| VZV | 4 | 7 | 7 | 4 | 4 | 11 | 37 |

| Total | 10 | 9 | 10 | 5 | 6 | 13 | 53 |

| Immunological Status | Number of Cases |

|---|---|

| No data available | 25 |

| Immunocompetent | 16 |

| Hepatic cirrhosis | 1 |

| Malignancies | 5 |

| Myasthenia Gravis | 1 |

| CLL | 1 |

| Rheumatoid Arthritis | 1 |

| SLE | 2 |

| Diabetes Mellitus Type 2 | 1 |

| Positive MRI | Negative MRI | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| HSV-1 | 6 | 1 | 7 |

| HSV-2 | 1 | 3 | 4 |

| VZV | 9 | 11 | 20 |

| Total | 16 | 15 | 31 |

| Virus | Cells (per mm3) | Glucose (mg/dL) | Protein (mg/dL) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HSV-1 | N | 8 | 8 | 8 |

| Mean | 43.25 | 64.13 | 67.94 | |

| Median | 26 | 59.50 | 53.05 | |

| Minimum | 1 | 52 | 34.5 | |

| Maximum | 124 | 95 | 122.7 | |

| HSV-2 | N | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| Mean | 220.67 | 46.5 | 124.82 | |

| Median | 231 | 42 | 131.85 | |

| Minimum | 107 | 31 | 71 | |

| Maximum | 350 | 76 | 185 | |

| VZV | N | 32 | 31 | 31 |

| Mean | 312.38 | 59.55 | 97.67 | |

| Median | 125 | 56 | 85.2 | |

| Minimum | 1 | 39 | 34 | |

| Maximum | 1860 | 118 | 245.8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kakouris, V.; Kalyva, N.; Militsopoulou, M.; Stamouli, V.; Meletis, G.; Kachrimanidou, M.; Paliogianni, F. Epidemiology of Herpes Simplex and Varicella Zoster Virus-Associated Central Nervous System Infections in Western Greece: A Five-Year Retrospective Analysis. Pathogens 2026, 15, 30. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens15010030

Kakouris V, Kalyva N, Militsopoulou M, Stamouli V, Meletis G, Kachrimanidou M, Paliogianni F. Epidemiology of Herpes Simplex and Varicella Zoster Virus-Associated Central Nervous System Infections in Western Greece: A Five-Year Retrospective Analysis. Pathogens. 2026; 15(1):30. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens15010030

Chicago/Turabian StyleKakouris, Vasileios, Niki Kalyva, Maria Militsopoulou, Vassiliki Stamouli, Georgios Meletis, Melina Kachrimanidou, and Fotini Paliogianni. 2026. "Epidemiology of Herpes Simplex and Varicella Zoster Virus-Associated Central Nervous System Infections in Western Greece: A Five-Year Retrospective Analysis" Pathogens 15, no. 1: 30. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens15010030

APA StyleKakouris, V., Kalyva, N., Militsopoulou, M., Stamouli, V., Meletis, G., Kachrimanidou, M., & Paliogianni, F. (2026). Epidemiology of Herpes Simplex and Varicella Zoster Virus-Associated Central Nervous System Infections in Western Greece: A Five-Year Retrospective Analysis. Pathogens, 15(1), 30. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens15010030