Tapeworms in an Apex Predator: First Molecular Identification of Taenia krabbei and Taenia hydatigena in Wolves (Canis lupus) from Romania

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Diagnostic Procedures

2.1.1. Necropsy Examination

2.1.2. Molecular Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sinclair, R.E.; Fryxell, J. Wildlife Ecology, Conservation and Management, 2nd ed.; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2006; pp. 78–89. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Sabi, M.N.S.; Rääf, L.; Osterman-Lind, E.; Uhlhorn, H.; Kapel, C.M.O. Gastrointestinal helminths of gray wolves (Canis lupus lupus) from Sweden. Parasitol. Res. 2018, 117, 1891–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagrade, G.; Kirjušina, M.; Vismanis, K.; Ozoliņš, J. Helminth parasites of the wolf (Canis lupus) from Latvia. J. Helminthol. 2009, 83, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bindke, J.D.; Springer, A.; Böer, M.; Strube, C. Helminth fauna in captive European gray wolves (Canis lupus lupus) in Germany. Front. Vet. Sci. 2017, 4, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ćirović, D.; Pavlović, I.; Penezić, A. Intestinal helminth parasites of the grey wolf (Canis lupus L.) in Serbia. Acta Vet. Hung. 2015, 63, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craig, H.L.; Craig, P.S. Helminth parasites of wolves (Canis lupus): A species list and an analysis of published prevalence studies in Nearctic and Palaearctic populations. J. Helminthol. 2005, 79, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, A.L.; Mateus, T.L.; Llaneza, L.; Vieira-Pinto, M.M.; Madeira de Carvalho, L.M. Gastrointestinal parasites in Iberian wolf (Canis lupus signatus) from the Iberian Peninsula. Parasitologia 2023, 3, 15–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schurer, J.M.; Pawlik, M.; Huber, A.; Elkin, B.; Cluff, H.D.; Pongracz, J.D.; Gesy, K.; Wagner, B.; Dixon, B.; Merks, H.; et al. Intestinal parasites of gray wolves (Canis lupus) in northern and western Canada. Can. J. Zool. 2016, 94, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segovia, J.M.; Torres, J.; Miquel, J.; Llaneza, L.; Feliu, C. Helminths in the wolf (Canis lupus) from north-western Spain. J. Helminthol. 2001, 75, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umhang, G.; Duchamp, C.; Boucher, J.-M.; Caillot, C.; Legras, L.; Demerson, J.-M.; Lucas, J.; Gauthier, D.; Boué, F. Gray wolves as sentinels for the presence of Echinococcus spp. and other gastrointestinal parasites in France. Int. J. Parasitol. Parasites Wildl. 2023, 22, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Formenti, N.; Chiari, M.; Trogu, T.; Gaffuri, A.; Garbarino, C.; Boniotti, M.B.; Corradini, C.; Lanfranchi, P.; Ferrari, N. Molecular identification of cryptic cysticercosis: Taenia ovis krabbei in wild intermediate and domestic definitive hosts. J. Helminthol. 2018, 92, 203–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoberg, E.P. Taenia tapeworms: Their biology, evolution and socioeconomic significance. Microbes Infect. 2002, 4, 859–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bariselli, S.; Maioli, G.; Pupillo, G.; Calzolari, M.; Torri, D.; Cirasella, L.; Luppi, A.; Torreggiani, C.; Garbarino, C.; Barsi, F.; et al. Identification and phylogenetic analysis of Taenia spp. parasites found in wildlife in the Emilia-Romagna region, northern Italy (2017–2022). Int. J. Parasitol. Parasites Wildl. 2023, 22, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gori, F.; Armua-Fernandez, M.T.; Milanesi, P.; Serafini, M.; Magi, M.; Deplazes, P.; Macchioni, F. The occurrence of taeniids of wolves in Liguria (northern Italy). Int. J. Parasitol. Parasites Wildl. 2015, 4, 252–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juránková, J.; Hulva, P.; Černá Bolfíková, B.; Hrazdilová, K.; Frgelecová, L.; Daněk, O.; Modrý, D. Identification of tapeworm species in genetically characterised grey wolves recolonising Central Europe. Acta Parasitol. 2021, 66, 1053–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Letková, V.; Lazar, P.; Soroka, J.; Goldová, M.; Čurlík, J. Epizootiology of game cervid cysticercosis. Nat. Croat. 2008, 17, 311–318. [Google Scholar]

- Lavikainen, A.; Laaksonen, S.; Beckmen, K.; Oksanen, A.; Isomursu, M.; Meri, S. Molecular identification of Taenia spp. in wolves (Canis lupus), brown bears (Ursus arctos) and cervids from North Europe and Alaska. Parasitol. Int. 2011, 60, 289–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priemer, J.; Krone, O.; Schuster, R. Taenia krabbei (Cestoda: Cyclophyllidea) in Germany and its delimitation from T. ovis. Zool. Anz. 2002, 241, 333–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoeks, S.; Huijbregts, M.A.J.; Busana, M.; Harfoot, M.B.J.; Svenning, J.-C.; Santini, L. Mechanistic insights into the role of large carnivores for ecosystem structure and functioning. Ecography 2020, 43, 1752–1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandu, R. Trophic relationships between wolf and deer from the south of the Făgăraș Mountains (Argeș District, Romania). Rom. J. Biol. Zool. 2010, 55, 185–192. [Google Scholar]

- Article 17 Web Tool—Species Assessments at Member State Level. European Environment Agency (Eionet). Available online: https://nature-art17.eionet.europa.eu/article17/species/report/ (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- Cazacu, C.; Adamescu, M.C.; Ionescu, O. Mapping trends of large and medium size carnivores of conservation interest in Romania. Ann. For. Res. 2014, 57, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurj, R.; Ionescu, O. Raport final pentru “Studiul privind estimarea populațiilor de carnivore mari și pisică sălbatică din România (Ursus arctos, Canis lupus, Lynx lynx și Felis silvestris) 2011–2012”. In Final Report; Fundația Carpați, Institutul de Cercetări și Amenajări Silvice, Universitatea Transilvania din Brașov: Brașov, Romania, 2011. (In Romanian) [Google Scholar]

- Sin, T.; Gazzola, A.; Chiriac, S.; Rîșnoveanu, G. Wolf diet and prey selection in the Southeastern Carpathian Mountains, Romania. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0225424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corradini, A. Wolf (Canis lupus) in Romania: Winter Feeding Ecology and Spatial Interaction with Lynx (Lynx lynx). Doctoral Dissertation, Università degli Studi di Firenze (Scuola di Agraria), Florence, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Gherman, C.; Cozma, V.; Mircean, V.; Brudașcă, F.; Rus, N.; Deteșan, A. Zoonoze helmintice la specii de carnivore sălbatice din fauna României. Sci. Parasitol. 2002, 3, 17–21. [Google Scholar]

- Ordinul Ministrului Mediului, Apelor și Pădurilor nr. 1571/07.06.2022 Privind Aprobarea Cotelor de Recoltă Pentru Unele specii de Faună de Interes Cinegetic. Available online: https://mmediu.ro/articol/ordinul-ministrului-mediului-apelor-si-padurilor-nr-1571 (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- Ordonanța de Urgență nr. 57/2007, (2007), Regime of Natural Protected Areas, Conservation of Natural Habitats, Flora and Fauna. Available online: https://lege5.ro/App/Document/geydqobuge/ordonanta-de-urgenta-nr-57-2007-privind-regimul-ariilor-naturale-protejate-conservarea-habitatelor-naturale-a-florei-si-faunei-salbatice (accessed on 19 October 2025). (In Romanian).

- World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH). Available online: https://www.woah.org/en/home/ (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA). Available online: https://www.efsa.europa.eu/en (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- Zajac, A.M.; Conboy, G.A.; Little, S.E.; Reichard, M.V. Veterinary Clinical Parasitology, 9th ed.; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2021; p. 432. [Google Scholar]

- Bowles, J.; Blair, D.; McManus, D.P. Genetic variants within the genus Echinococcus identified by mitochondrial sequencing. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 1992, 54, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bart, J.-M.; Knapp, J.; Gottstein, B.; El-Garch, F.; Giraudoux, P.; Glowatzki, M.-L.; Berthoud, H.; Maillard, S.; Piarroux, R. EmsB, a tandem repeated multi-loci microsatellite, new tool to investigate the genetic diversity of Echinococcus multilocularis. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2006, 6, 390–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowles, J.; McManus, D.P. NADH dehydrogenase 1 gene sequences compared for species and strains of the genus Echinococcus. Int. J. Parasitol. 1993, 23, 969–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinkel, A.; Njoroge, E.M.; Zimmermann, A.; Wälz, M.; Zeyhle, E.; Elmahdi, I.E.; Mackenstedt, U.; Romig, T. A PCR system for detection of species and genotypes of the Echinococcus granulosus-complex, with reference to the epidemiological situation in eastern Africa. Int. J. Parasitol. 2004, 34, 645–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Library of Medicine. Available online: http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- QIAGEN CLC Genomics Workbench. Available online: https://digitalinsights.qiagen.com (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- Poglayen, G.; Gori, F.; Morandi, B.; Galuppi, R.; Fabbri, E.; Caniglia, R.; Milanesi, P.; Galaverni, M.; Randi, E.; Marchesi, B.; et al. Italian wolves (Canis lupus italicus Altobello, 1921) and molecular detection of taeniids in the Foreste Casentinesi National Park, Northern Italian Apennines. Int. J. Parasitol. Parasites Wildl. 2017, 6, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erol, U.; Danyer, E.; Sarimehmetoğlu, H.O.; Utuk, A.E. First parasitological data on a wild grey wolf in Turkey with morphological and molecular confirmation of the parasites. Acta Parasitol. 2021, 66, 687–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bindke, J.D.; Springer, A.; Janecek-Erfurth, E.; Böer, M.; Strube, C. Helminth infections of wild European gray wolves (Canis lupus Linnaeus, 1758) in Lower Saxony, Germany, and comparison to captive wolves. Parasitol. Res. 2019, 118, 701–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filip, K.J.; Pyziel, A.M.; Jeżewski, W.; Myczka, A.W.; Demiaszkiewicz, A.W.; Laskowski, Z. First molecular identification of Taenia hydatigena in wild ungulates in Poland. EcoHealth 2019, 16, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Puerta, L.A.; Pacheco, J.; Gonzales-Viera, O.; Lopez-Urbina, M.T.; Gonzalez, A.E.; Cysticercosis Working Group in Peru. The taruca (Hippocamelus antisensis) and the red brocket deer (Mazama americana) as intermediate hosts of Taenia hydatigena in Peru, morphological and molecular evidence. Vet. Parasitol. 2015, 212, 465–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalandarishvili, A.; Feher, A.; Katona, K. Differences in livestock consumption by grey wolf, golden jackal, coyote and stray dog revealed by a systematic review. Hystrix Ital. J. Mammal. 2024, 35, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Hărdălău, D.; Fedorca, M.; Popovici, D.C.; Ionescu, G.; Fedorca, A.; Mirea, I.; Iordache, D.; Ionescu, O. Insights in managing ungulates population and forest sustainability in Romania. Diversity 2025, 17, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iosif, R.; Skrbinšek, T.; Erős, N.; Konec, M.; Boljte, B.; Jan, M.; Promberger-Fürpass, B. Wolf population size and composition in one of Europe’s strongholds, the Romanian Carpathians. Ecol. Evol. 2025, 15, e71200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macchioni, F.; Coppola, F.; Furzi, F.; Gabrielli, S.; Baldanti, S.; Boni, C.B.; Felicioli, A. Taeniid cestodes in a wolf pack living in a highly anthropic hilly agro-ecosystem. Parasite 2021, 28, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crotti, S.; Spina, S.; Cruciani, D.; Bonelli, P.; Felici, A.; Gavaudan, S.; Gobbi, M.; Morandi, F.; Piseddu, T.; Torricelli, M.; et al. Tapeworms detected in wolf populations in Central Italy (Umbria and Marche regions): A long-term study. Int. J. Parasitol. Parasites Wildl. 2023, 21, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karamon, J.; Samorek-Pieróg, M.; Bilska-Zając, E.; Korpysa-Dzirba, W.; Sroka, J.; Zdybel, J.; Cencek, T. The grey wolf (Canis lupus) as a host of Echinococcus multilocularis, E. granulosus s.l. and other helminths—A new zoonotic threat in Poland. J. Vet. Res. 2024, 68, 539–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider, A.; Moré, G.; Pewsner, M.; Frey, C.F.; Basso, W. Cestodes in Eurasian wolves (Canis lupus lupus) and domestic dogs (Canis lupus familiaris) in Switzerland. Int. J. Parasitol. Parasites Wildl. 2025, 26, 101027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jędrzejewski, W.; Niedziałkowska, M.; Hayward, M.W.; Goszczyński, J.; Jędrzejewska, B.; Borowik, T.; Bartoń, K.A.; Nowak, S.; Harmuszkiewicz, J.; Juszczyk, A.; et al. Prey choice and diet of wolves related to ungulate communities and wolf subpopulations in Poland. J. Mammal. 2012, 93, 1480–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, S.; Mysłajek, R.W.; Jędrzejewska, B. Patterns of wolf (Canis lupus) predation on wild and domestic ungulates in the Western Carpathian Mountains (S Poland). Acta Theriol. 2005, 50, 263–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

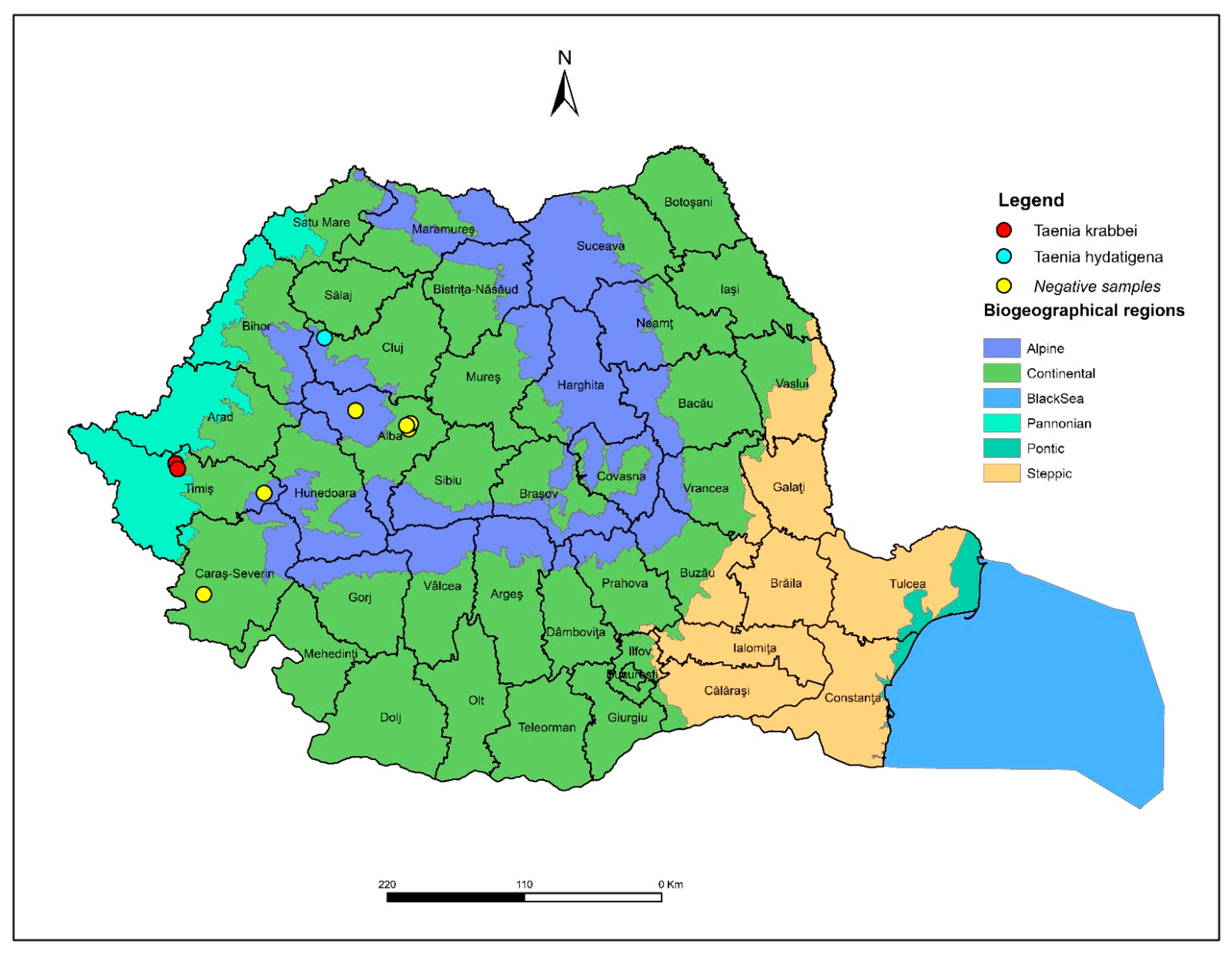

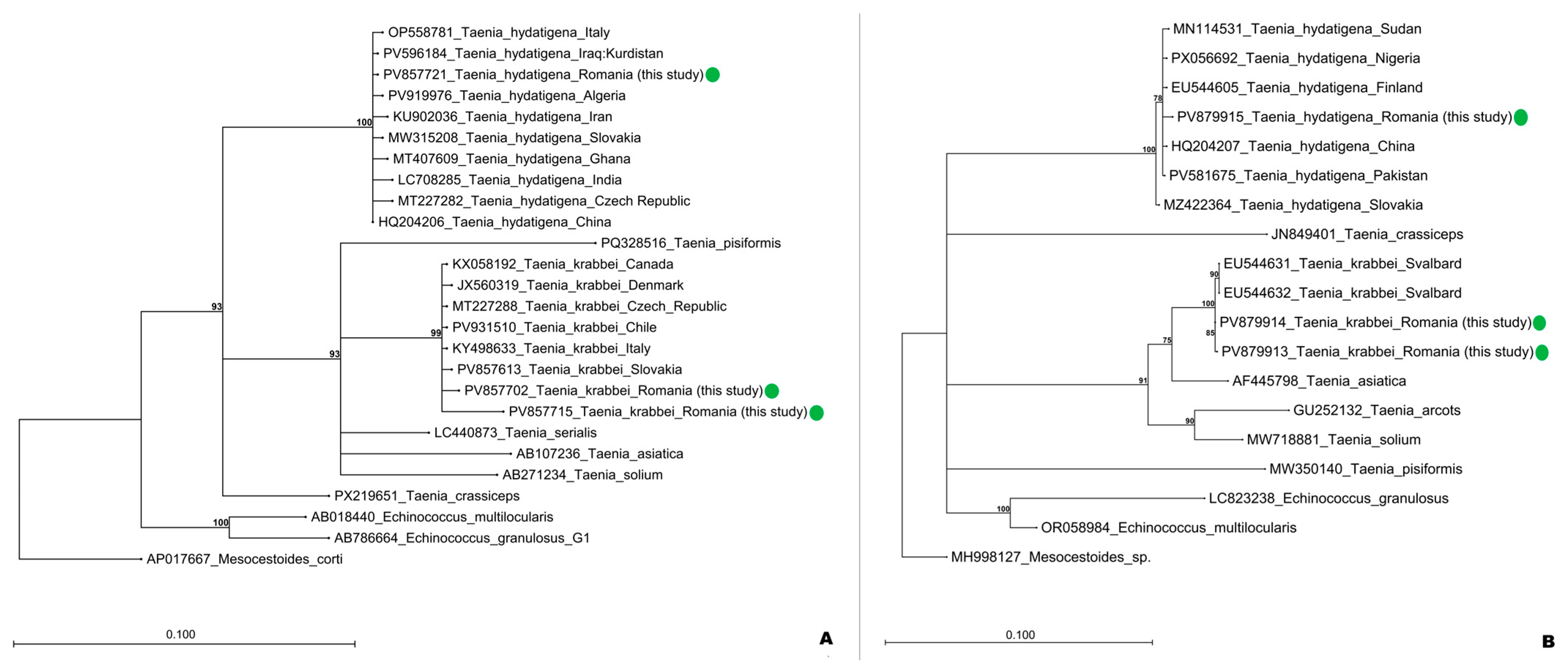

| Wolf ID | County | Parasite Burden (n) | Species Identified | Molecular Markers Amplified | GenBank Accession Numbers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| W1 | Timiș | 9 | Taenia krabbei | cox1, nad1, 12S | PV857702; PV857764; PV879913 |

| W2 | Timiș | 18 | Taenia krabbei | cox1, nad1, 12S | PV857715; PV857765; PV879914 |

| W3 | Cluj | 9 | Taenia hydatigena | cox1, nad1 | PV857721; PV879915 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Moraru, M.M.F.; Marin, A.-M.; Popovici, D.-C.; Santoro, A.; Casulli, A.; Morariu, S.; Ilie, M.S.; Igna, V.; Mederle, N. Tapeworms in an Apex Predator: First Molecular Identification of Taenia krabbei and Taenia hydatigena in Wolves (Canis lupus) from Romania. Pathogens 2026, 15, 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens15010018

Moraru MMF, Marin A-M, Popovici D-C, Santoro A, Casulli A, Morariu S, Ilie MS, Igna V, Mederle N. Tapeworms in an Apex Predator: First Molecular Identification of Taenia krabbei and Taenia hydatigena in Wolves (Canis lupus) from Romania. Pathogens. 2026; 15(1):18. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens15010018

Chicago/Turabian StyleMoraru, Maria Monica Florina, Ana-Maria Marin, Dan-Cornel Popovici, Azzurra Santoro, Adriano Casulli, Sorin Morariu, Marius Stelian Ilie, Violeta Igna, and Narcisa Mederle. 2026. "Tapeworms in an Apex Predator: First Molecular Identification of Taenia krabbei and Taenia hydatigena in Wolves (Canis lupus) from Romania" Pathogens 15, no. 1: 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens15010018

APA StyleMoraru, M. M. F., Marin, A.-M., Popovici, D.-C., Santoro, A., Casulli, A., Morariu, S., Ilie, M. S., Igna, V., & Mederle, N. (2026). Tapeworms in an Apex Predator: First Molecular Identification of Taenia krabbei and Taenia hydatigena in Wolves (Canis lupus) from Romania. Pathogens, 15(1), 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens15010018