Antiviral Role of Surface Layer Protein A (SlpA) of Lactobacillus acidophilus

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

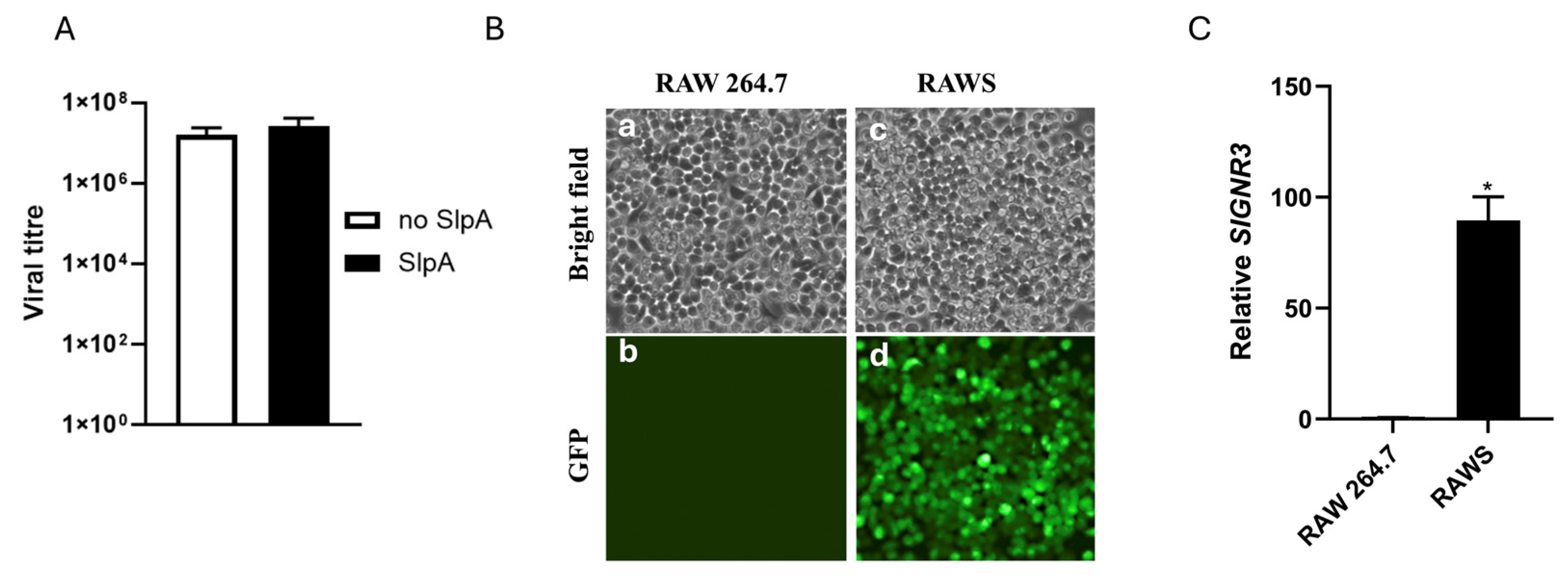

3.1. Construction of Chimeric RAW 264.7 Cells Expressing the Murine SIGNR3 Gene

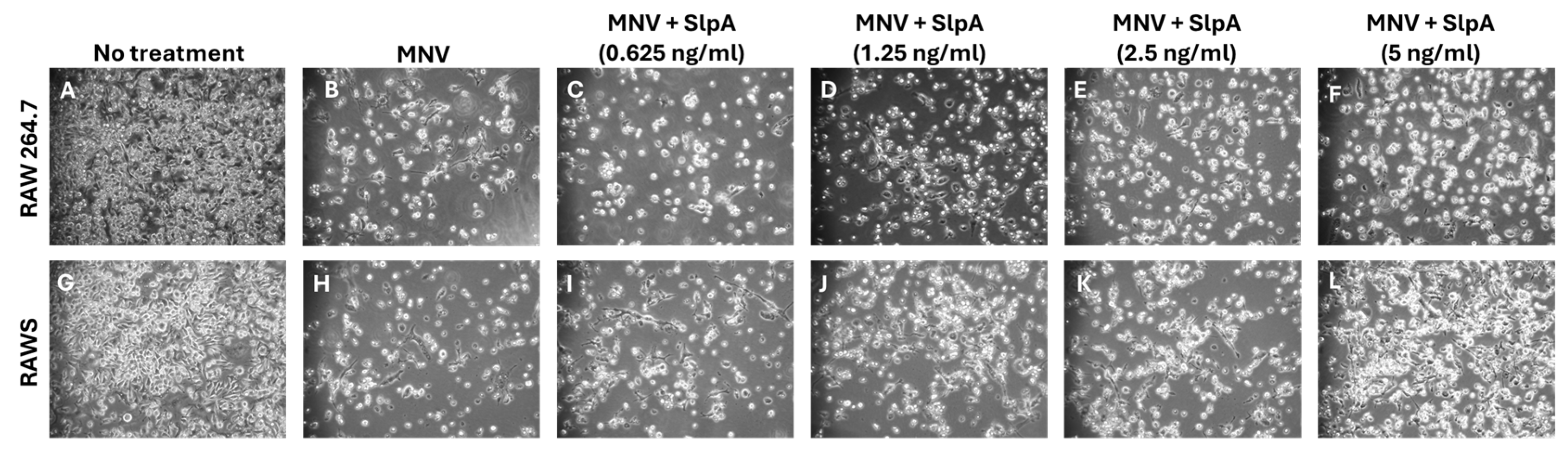

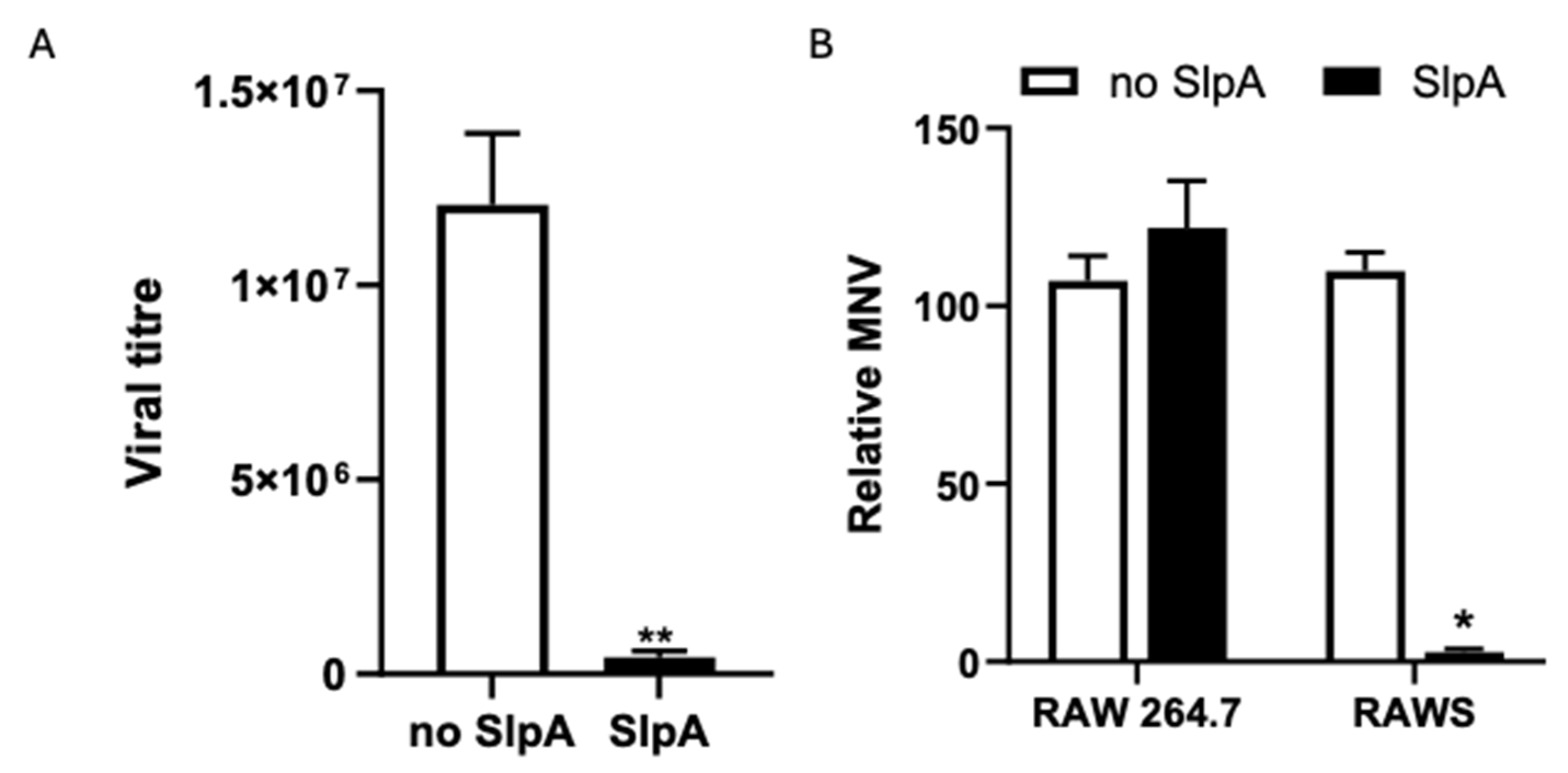

3.2. SlpA Treatment Prevents MNV Replication

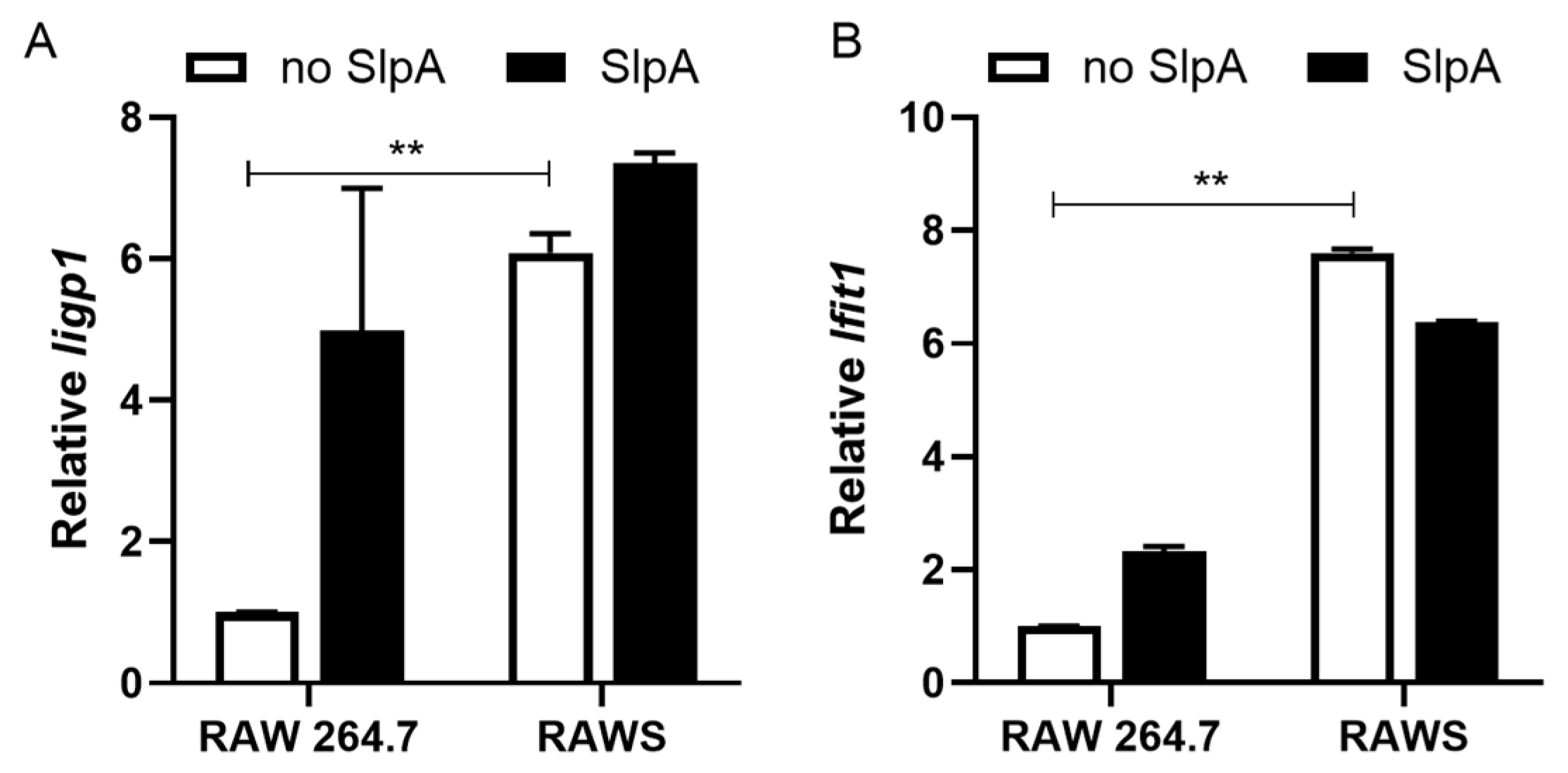

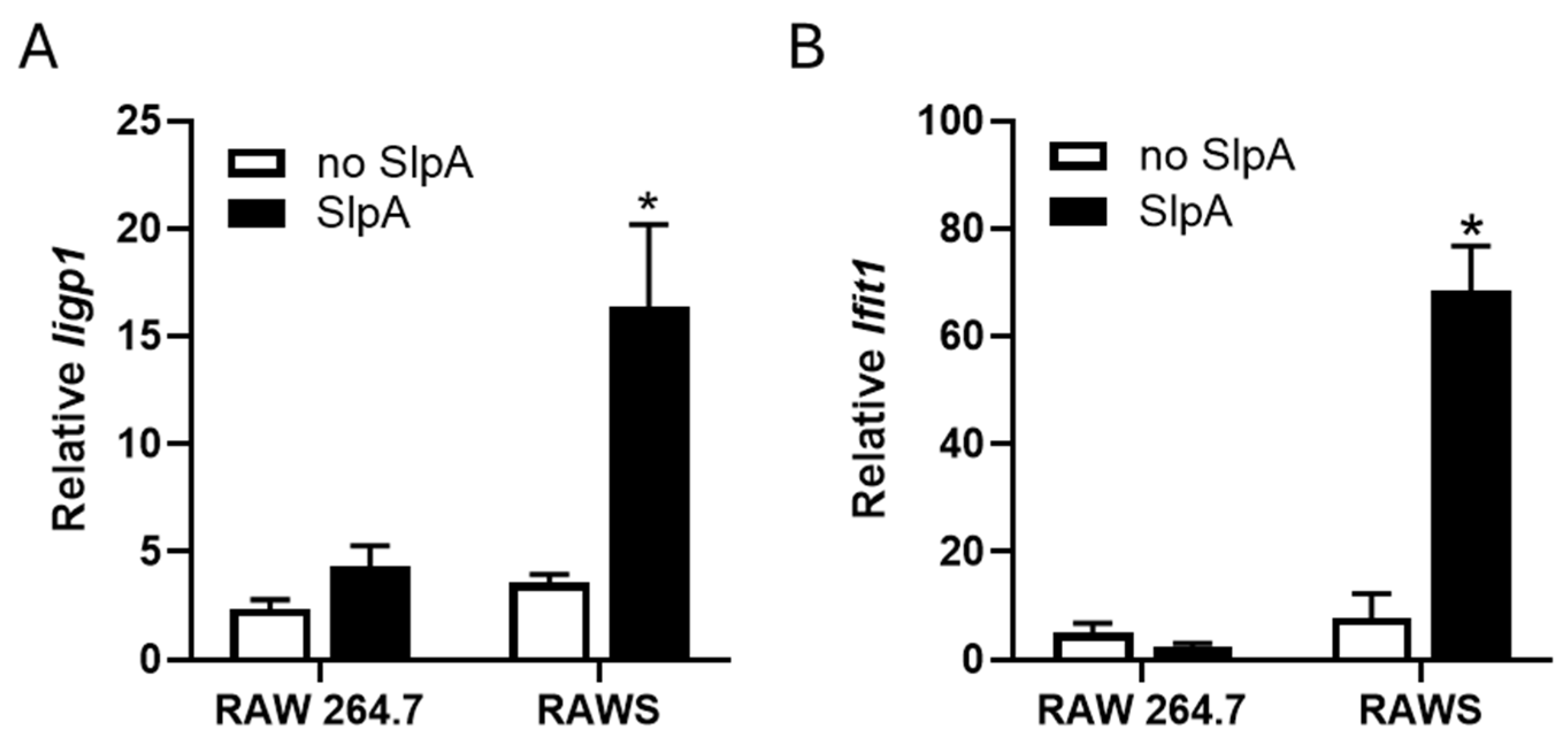

3.3. Presence of Signr3 and SlpA Treatment Enhances Antiviral Gene Signature

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Patents

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| RAW | RAW 264.7 cells |

| RAWS | RAW 264.7 cells expressing murine SIGNR3 cells |

| SlpA | Surface Layer Protein A |

References

- Liu, L.-J.; Liu, W.; Liu, Y.-X.; Xiao, H.-J.; Jia, N.; Liu, G.; Tong, Y.-G.; Cao, W.-C. Identification of Norovirus as the Top Enteric Viruses Detected in Adult Cases with Acute Gastroenteritis. Am. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2010, 82, 717–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robilotti, E.; Deresinski, S.; Pinsky, B.A. Norovirus. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2015, 28, 134–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haessler, S.; Granowitz, E.V. Norovirus gastroenteritis in immunocompromised patients. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 368, 971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baldridge, M.T.; Turula, H.; Wobus, C.E. Norovirus Regulation by Host and Microbe. Trends Mol. Med. 2016, 22, 1047–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parra, G.I.; Squires, R.B.; Karangwa, C.K.; Johnson, J.A.; Lepore, C.J.; Sosnovtsev, S.V.; Green, K.Y. Static and Evolving Norovirus Genotypes: Implications for Epidemiology and Immunity. PLoS Pathog. 2017, 13, e1006136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrino, T.A.; Schreiber, D.S.; Trier, J.S.; Kapikian, A.Z.; Blacklow, N.R. Clinical Immunity in Acute Gastroenteritis Caused by Norwalk Agent. N. Engl. J. Med. 1977, 297, 86–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons, K.; Gambhir, M.; Leon, J.; Lopman, B. Duration of immunity to norovirus gastroenteritis. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2013, 19, 1260–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bányai, K.; Estes, M.K.; Martella, V.; Parashar, U.D. Viral gastroenteritis. Lancet 2018, 392, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wobus, C.E.; Thackray, L.B.; Virgin, H.W. Murine Norovirus: A Model System To Study Norovirus Biology and Pathogenesis. J. Virol. 2006, 80, 5104–5112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirneisen, K.A.; Kniel, K.E. Comparing Human Norovirus Surrogates: Murine Norovirus and Tulane Virus. J. Food Prot. 2013, 76, 139–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilliland, S.E.; Speck, M.L.; Morgan, C.G. Detection of Lactobacillus acidophilus in Feces of Humans, Pigs, and Chickens. Appl. Microbiol. 1975, 30, 541–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanders, M.E.; Klaenhammer, T.R. Invited review: The scientific basis of Lactobacillus acidophilus NCFM functionality as a probiotic. J. Dairy Sci. 2001, 84, 319–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altermann, E.; Russell, W.M.; Azcarate-Peril, M.A.; Barrangou, R.; Buck, B.L.; McAuliffe, O.; Souther, N.; Dobson, A.; Duong, T.; Callanan, M. Complete genome sequence of the probiotic lactic acid bacterium Lactobacillus acidophilus NCFM. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 3906–3912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klaenhammer, T.R.; Barrangou, R.; Buck, B.L.; Azcarate-Peril, M.A.; Altermann, E. Genomic features of lactic acid bacteria effecting bioprocessing and health. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2005, 29, 393–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klaenhammer, T.R.; Altermann, E.; Pfeiler, E.; Buck, B.L.; Goh, Y.-J.; O’Flaherty, S.; Barrangou, R.; Duong, T. Functional genomics of probiotic Lactobacilli. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2008, 42, S160–S162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebeer, S.; Vanderleyden, J.; De Keersmaecker, S.C. Host interactions of probiotic bacterial surface molecules: Comparison with commensals and pathogens. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2010, 8, 171–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bron, P.A.; Tomita, S.; Mercenier, A.; Kleerebezem, M. Cell surface-associated compounds of probiotic lactobacilli sustain the strain-specificity dogma. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2013, 16, 262–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, Y.J.; Azcárate-Peril, M.A.; O’Flaherty, S.; Durmaz, E.; Valence, F.; Jardin, J.; Lortal, S.; Klaenhammer, T.R. Development and Application of a upp-Based Counterselective Gene Replacement System for the Study of the S-Layer Protein SlpX of Lactobacillus acidophilus NCFM. Appl. Envrion. Microbiol. 2009, 75, 3093–3105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Call, E.K.; Goh, Y.J.; Selle, K.; Klaenhammer, T.R.; O’Flaherty, S. Sortase-deficient lactobacilli: Effect on immunomodulation and gut retention. Microbiology 2015, 161, 311–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Flaherty, S.J.; Klaenhammer, T.R. Functional and phenotypic characterization of a protein from Lactobacillus acidophilus involved in cell morphology, stress tolerance and adherence to intestinal cells. Microbiology 2010, 156, 3360–3367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, Y.J.; Klaenhammer, T.R. Functional roles of aggregation-promoting-like factor in stress tolerance and adherence of Lactobacillus acidophilus NCFM. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2010, 76, 5005–5012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamadzadeh, M.; Pfeiler, E.A.; Brown, J.B.; Zadeh, M.; Gramarossa, M.; Managlia, E.; Bere, P.; Sarraj, B.; Khan, M.W.; Pakanati, K.C. Regulation of induced colonic inflammation by Lactobacillus acidophilus deficient in lipoteichoic acid. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 4623–4630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstantinov, S.R.; Smidt, H.; de Vos, W.M.; Bruijns, S.C.; Singh, S.K.; Valence, F.; Molle, D.; Lortal, S.; Altermann, E.; Klaenhammer, T.R.; et al. S layer protein A of Lactobacillus acidophilus NCFM regulates immature dendritic cell and T cell functions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 19474–19479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lightfoot, Y.L.; Selle, K.; Yang, T.; Goh, Y.J.; Sahay, B.; Zadeh, M.; Owen, J.L.; Colliou, N.; Li, E.; Johannssen, T.; et al. SIGNR3-dependent immune regulation by Lactobacillus acidophilus surface layer protein A in colitis. Embo J. 2015, 34, 881–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arukha, A.P.; Freguia, C.F.; Mishra, M.; Jha, J.K.; Kariyawasam, S.; Fanger, N.A.; Zimmermann, E.M.; Fanger, G.R.; Sahay, B. Lactococcus lactis Delivery of Surface Layer Protein A Protects Mice from Colitis by Re-Setting Host Immune Repertoire. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahay, B.; Ge, Y.; Colliou, N.; Zadeh, M.; Weiner, C.; Mila, A.; Owen, J.L.; Mohamadzadeh, M. Advancing the use of Lactobacillus acidophilus surface layer protein A for the treatment of intestinal disorders in humans. Gut Microbes 2015, 6, 392–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanaki, K.-I.; Ike, F.; Kajita, A.; Yasuno, W.; Yanagiba, M.; Goto, M.; Sakai, K.; Ami, Y.; Kyuwa, S. A Broadly Reactive One-Step SYBR Green I Real-Time RT-PCR Assay for Rapid Detection of Murine Norovirus. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e98108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahay, B.; Patsey, R.L.; Eggers, C.H.; Salazar, J.C.; Radolf, J.D.; Sellati, T.J. CD14 signaling restrains chronic inflammation through induction of p38-MAPK/SOCS-dependent tolerance. PLoS Pathog. 2009, 5, e1000687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, L.J.; Muench, H. A simple method of estimating fifty-percent endpoints. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1938, 27, 493–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biering, S.B.; Choi, J.; Halstrom, R.A.; Brown, H.M.; Beatty, W.L.; Lee, S.; McCune, B.T.; Dominici, E.; Williams, L.E.; Orchard, R.C.; et al. Viral Replication Complexes Are Targeted by LC3-Guided Interferon-Inducible GTPases. Cell Host Microbe 2017, 22, 74–85.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mears, H.V.; Emmott, E.; Chaudhry, Y.; Hosmillo, M.; Goodfellow, I.G.; Sweeney, T.R. Ifit1 regulates norovirus infection and enhances the interferon response in murine macrophage-like cells. Wellcome Open Res. 2019, 4, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanne, A.; Ma, B.; Boudou, F.; Tailleux, L.; Botella, H.; Badell, E.; Levillain, F.; Taylor, M.E.; Drickamer, K.; Nigou, J.; et al. A murine DC-SIGN homologue contributes to early host defense against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Exp. Med. 2009, 206, 2205–2220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graziano, V.R.; Walker, F.C.; Kennedy, E.A.; Wei, J.; Ettayebi, K.; Strine, M.S.; Filler, R.B.; Hassan, E.; Hsieh, L.L.; Kim, A.S.; et al. CD300lf is the primary physiologic receptor of murine norovirus but not human norovirus. PLoS Pathog. 2020, 16, e1008242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, S.; Yokota, K.; Igimi, S.; Kajikawa, A. Comparative analysis of immunological properties of S-layer proteins isolated from Lactobacillus strains. Microbiology 2019, 165, 188–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Åvall-Jääskeläinen, S.; Palva, A. Lactobacillus surface layers and their applications. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2005, 29, 511–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagmeister, T.; Gubensäk, N.; Buhlheller, C.; Grininger, C.; Eder, M.; Ðordić, A.; Millán, C.; Medina, A.; Murcia, P.A.S.; Berni, F.; et al. The molecular architecture of Lactobacillus S-layer: Assembly and attachment to teichoic acids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2401686121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assandri, M.H.; Malamud, M.; Trejo, F.M.; Serradell, M.d.l.A. S-layer proteins as immune players: Tales from pathogenic and non-pathogenic bacteria. Curr. Res. Microb. Sci. 2023, 4, 100187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celebioglu, H.U.; Svensson, B. Dietary Nutrients, Proteomes, and Adhesion of Probiotic Lactobacilli to Mucin and Host Epithelial Cells. Microorganisms 2018, 6, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taverniti, V.; Stuknyte, M.; Minuzzo, M.; Arioli, S.; De Noni, I.; Scabiosi, C.; Cordova, Z.M.; Junttila, I.; Hämäläinen, S.; Turpeinen, H.; et al. S-layer protein mediates the stimulatory effect of Lactobacillus helveticus MIMLh5 on innate immunity. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2013, 79, 1221–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosmillo, M.; Chaudhry, Y.; Nayak, K.; Sorgeloos, F.; Koo, B.-K.; Merenda, A.; Lillestol, R.; Drumright, L.; Zilbauer, M.; Goodfellow, I. Norovirus Replication in Human Intestinal Epithelial Cells Is Restricted by the Interferon-Induced JAK/STAT Signaling Pathway and RNA Polymerase II-Mediated Transcriptional Responses. mBio 2020, 11, e00215-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, F.; Kaufmann, S.H.E.; Zerrahn, J. IIGP, a member of the IFN inducible and microbial defense mediating 47 kDa GTPase family, interacts with the microtubule binding protein hook3. J. Cell Sci. 2004, 117, 1747–1756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, S.; Stegmann, F.; Gnanapragassam, V.S.; Lepenies, B. From structure to function—Ligand recognition by myeloid C-type lectin receptors. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2022, 20, 5790–5812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Vallejo, J.J.; van Kooyk, Y. Endogenous ligands for C-type lectin receptors: The true regulators of immune homeostasis. Immunol. Rev. 2009, 230, 22–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Primers | Sequences | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| MNV_F | 5′-ATGGTA/GGTCCCACGCCAC-3′ | [27] |

| MNV_R | 5′-TGCGCCATCACTCATCC-3′ | |

| Iigp1_F | 5′-GTAGTGTGCTCAATGTTGCTGTCAC-3′ | This Study |

| Iigp1_R | 5′-TACCTCCACCACCCCAGTTTTAGC-3′ | |

| Ifit1_F | 5′-TACAGGCTGGAGTGTGCTGAGA-3′ | This Study |

| Ifit1_R | 5′-CTCCACTTTCAGAGCCTTCGCA-3′ | |

| 18sRNA_F | 5′-ATAGCGTATATTAAAGTTG-3′ | [28] |

| 18sRNA_R | 5′-GTCCTATTCCATTATTCC-3′ | |

| SIGNR3_F | 5′-GGTCATTCCAGAGGATGAAGAG-3′ | This Study |

| SIGNR3-R | 5′-TCTTTGGGACTTGGAGAAGAAG-3′ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Anumanthan, G.; Arukha, A.P.; Mergia, A.; Sahay, B. Antiviral Role of Surface Layer Protein A (SlpA) of Lactobacillus acidophilus. Pathogens 2026, 15, 103. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens15010103

Anumanthan G, Arukha AP, Mergia A, Sahay B. Antiviral Role of Surface Layer Protein A (SlpA) of Lactobacillus acidophilus. Pathogens. 2026; 15(1):103. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens15010103

Chicago/Turabian StyleAnumanthan, Govindaraj, Ananta Prasad Arukha, Ayalew Mergia, and Bikash Sahay. 2026. "Antiviral Role of Surface Layer Protein A (SlpA) of Lactobacillus acidophilus" Pathogens 15, no. 1: 103. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens15010103

APA StyleAnumanthan, G., Arukha, A. P., Mergia, A., & Sahay, B. (2026). Antiviral Role of Surface Layer Protein A (SlpA) of Lactobacillus acidophilus. Pathogens, 15(1), 103. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens15010103