Ecological Perspectives on Leishmaniasis Parasitism Patterns: Evidence of Possible Alternative Vectors for Leishmania (Leishmania) infantum (syn. L. chagasi) and Leishmania (Viannia) braziliensis in Piauí, Brazil

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

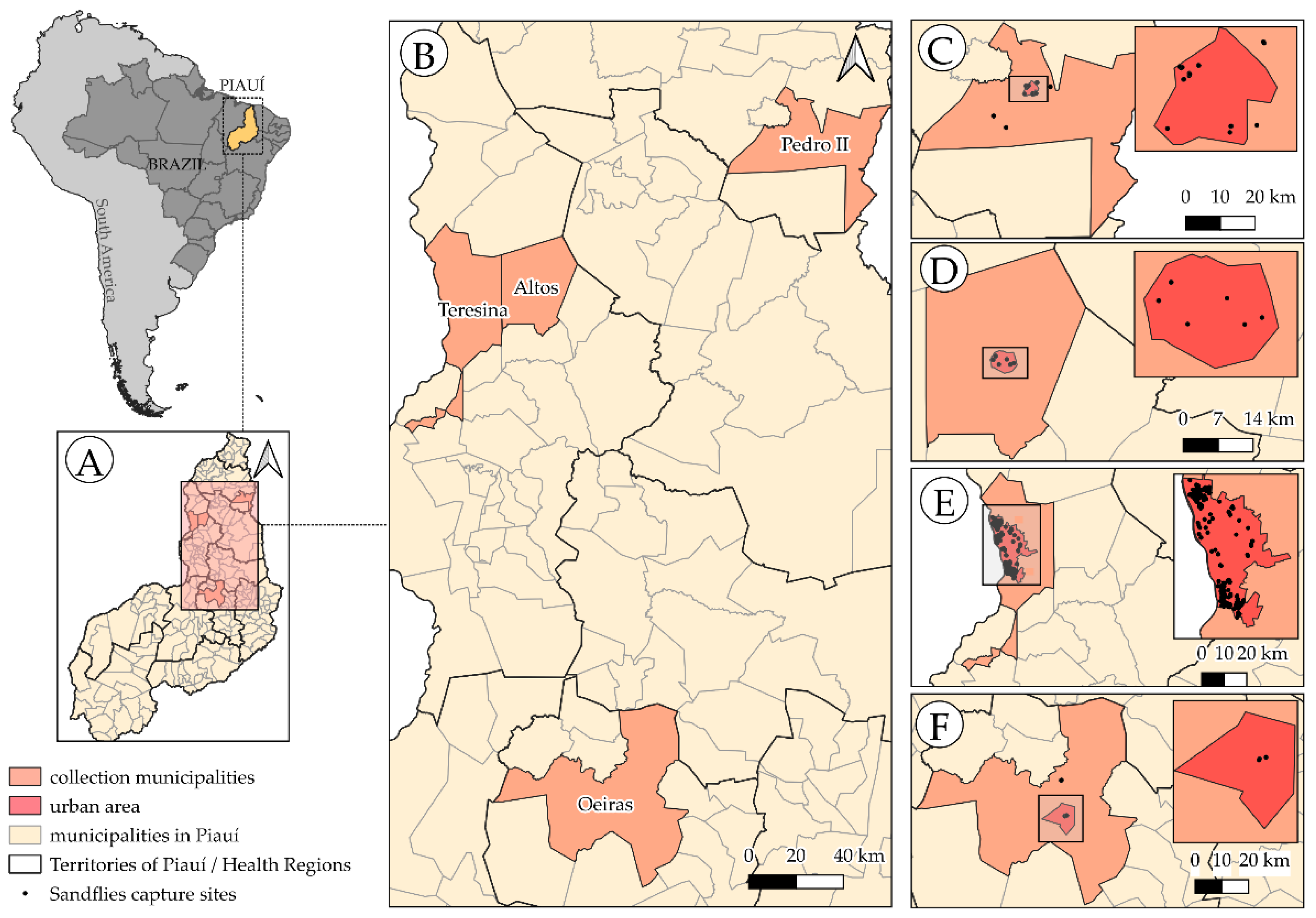

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Sandfly Collection and Morphological Identification

2.3. Analysis of Meteorological Data

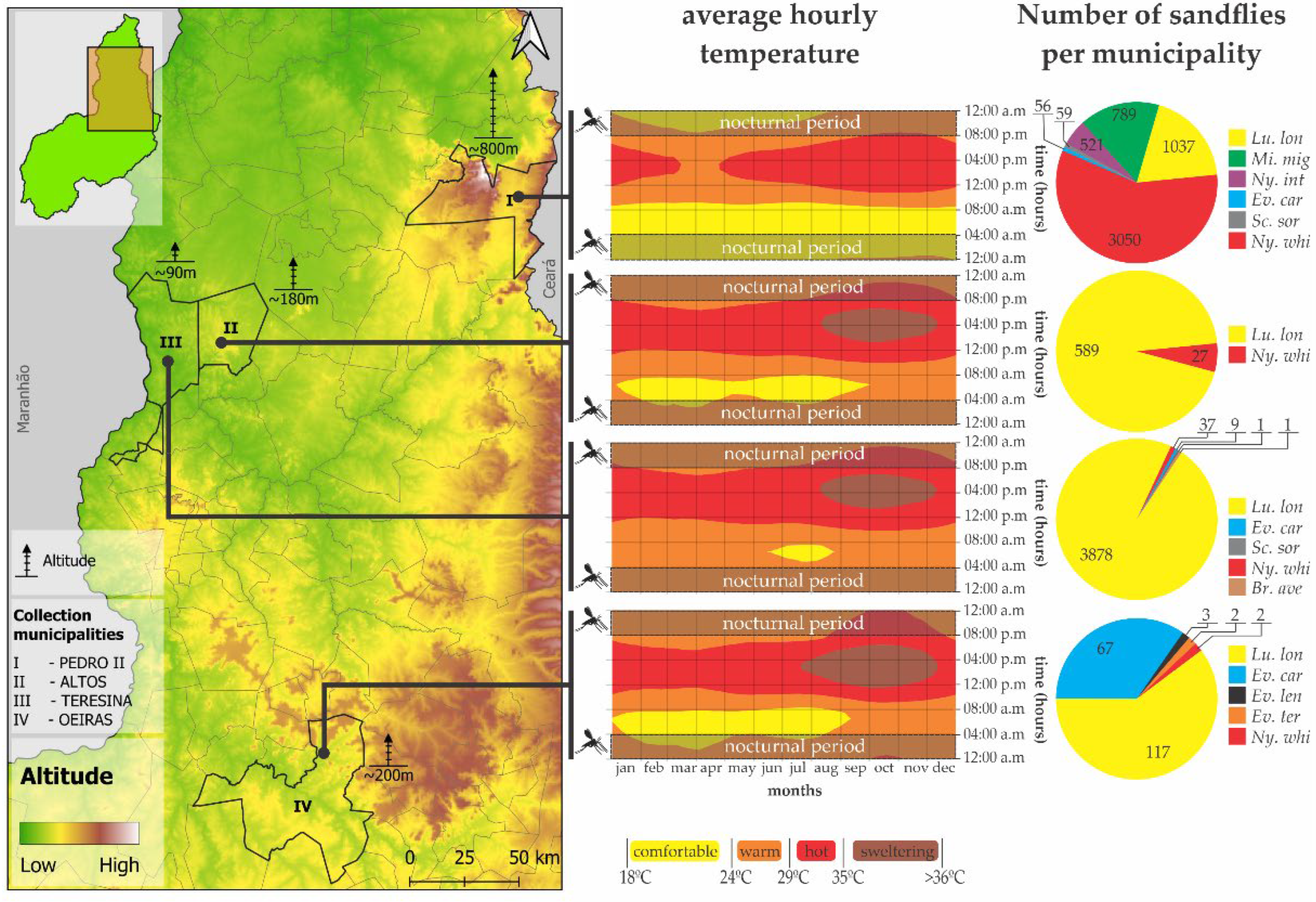

2.4. Relationship Between Altitude and Species of Sandflies

2.5. Detection of Leishmania spp. DNA

2.6. Identification of Leishmania spp.

2.7. Identification of Blood Food Sources of Engorged Females

2.8. Sample Sequencing

2.9. Data Analysis

2.10. Ethical Aspects

3. Results

3.1. Faunal Density of Sandflies

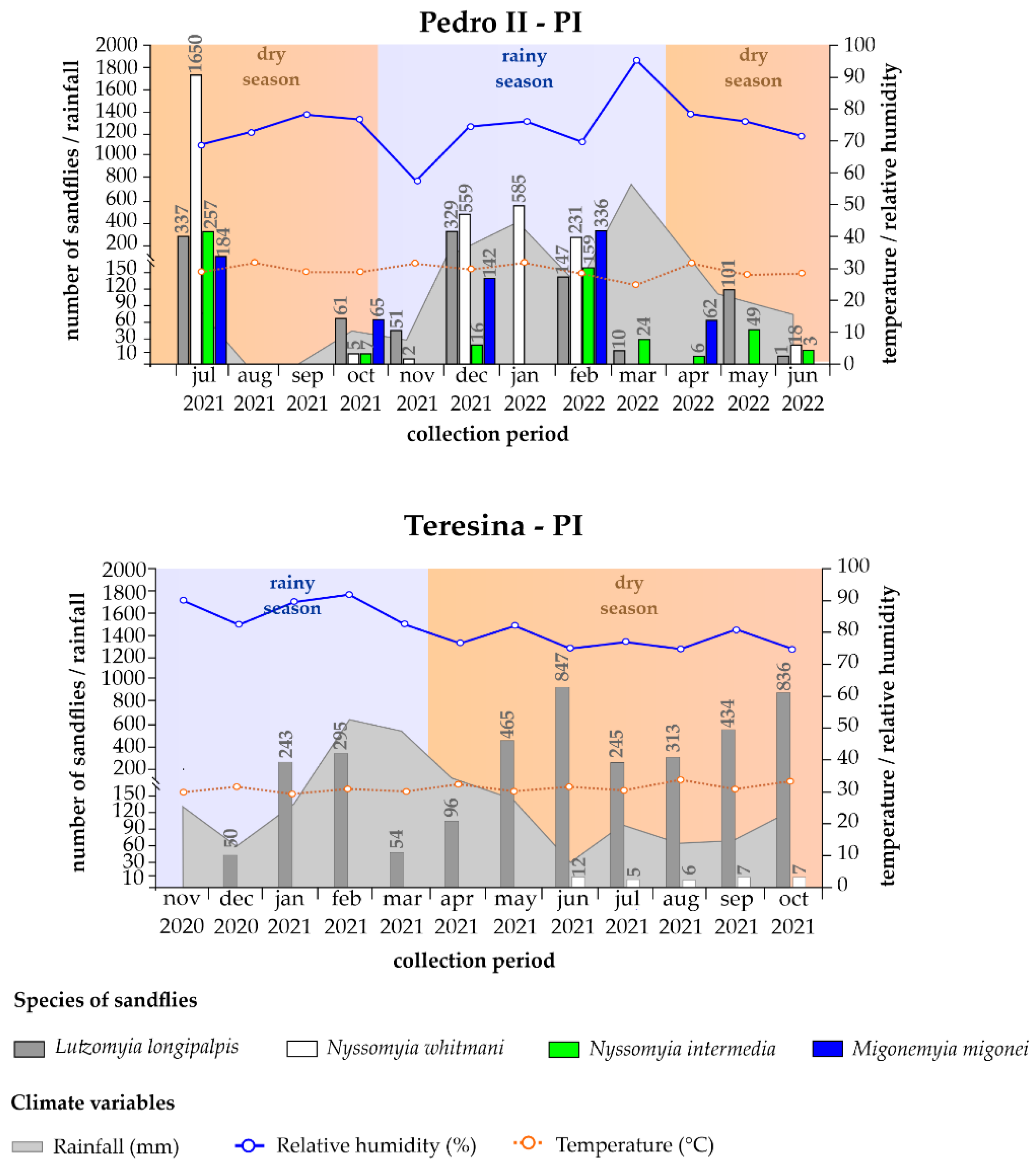

3.2. Climate Variables and Distribution of Sandflies

3.3. Relationship Between Altitude and Species of Sandflies

3.4. Ecological Analysis of the Altitudinal, Thermal, and Vector Distribution of Sandflies

3.5. Detection of Leishmania spp. DNA in Female Sandflies

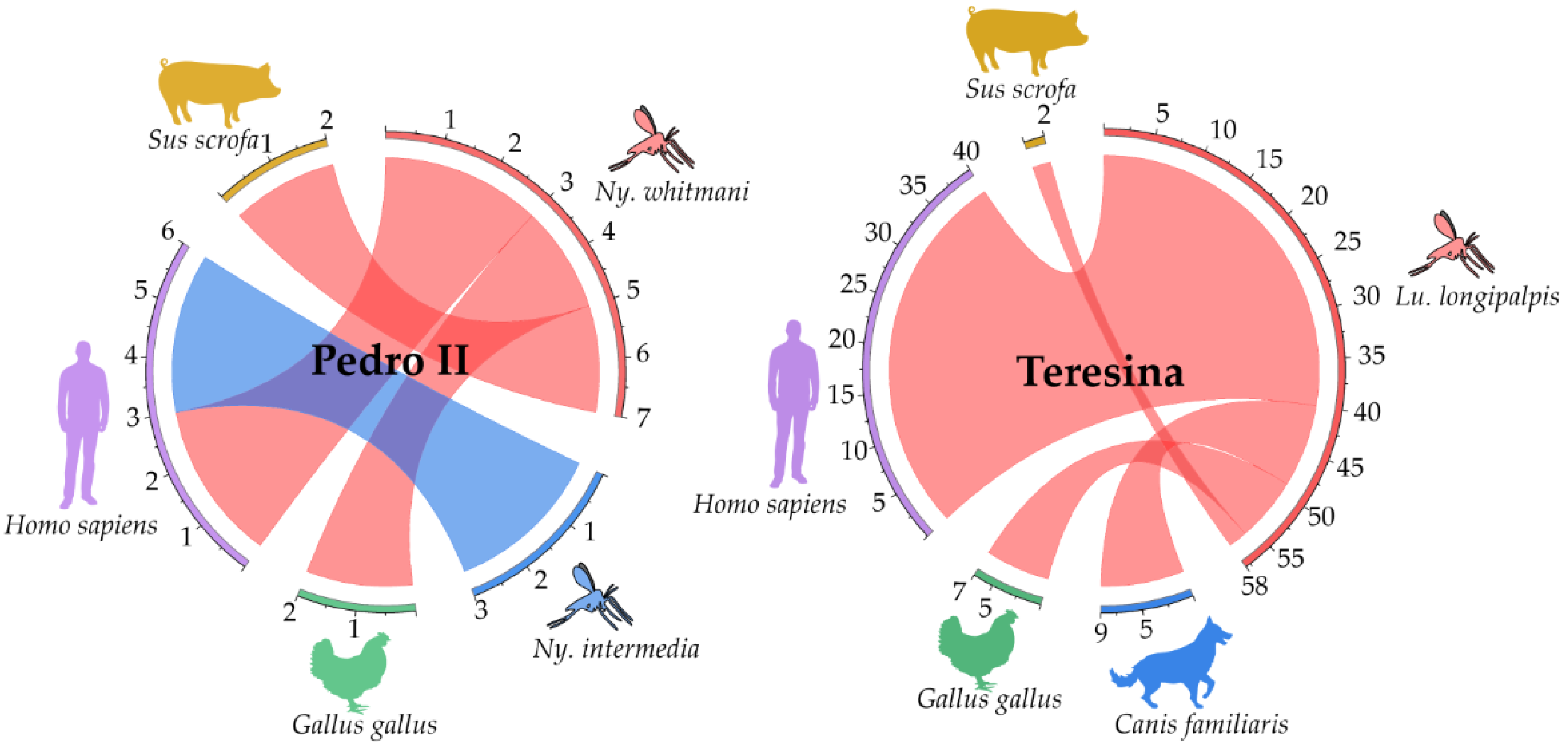

3.6. Analysis of Blood Sources in Engorged Female Sandflies

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| VL | Visceral Leishmaniasis |

| ACL | American Cutaneous Leishmaniasis |

| L | Leishmania |

| Lu. | Lutzomyia |

| Ny. | Nyssomyia |

| Mi. | Migonemyia |

| Ev. | Evandromyia |

| Sc. | Sciopemyia |

| Br. | Brumptomyia |

References

- World Health Organization WHO. Leishmaniasis. Available online: https://www.who.int/es/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/leishmaniasis (accessed on 6 June 2023).

- Mathison, B.A.; Bradley, B.T. Review of the Clinical Presentation, Pathology, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Leishmaniasis. Lab. Med. 2023, 54, 363–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leishmaniasis: Epidemiological Report for the Americas. No.11 (December 2022); Epidemiological Report of the Americas: OPAS/CDE/VT/22-0021; Pan American Health Organization: Washington, DC, USA, 2022; p. 12. Available online: https://iris.paho.org/handle/10665.2/56832 (accessed on 5 June 2023).

- Sacks, D.L. Leishmania–sand fly interactions controlling species-specific vector competence. Cell Microb. 2001, 3, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carvalho-Silva, R.; Ribeiro-da-Silva, R.C.; Cruz, L.N.P.D.; Oliveira, M.S.; Amoedo, P.M.; Rebêlo, J.M.M.; Guimarães-e-Silva, A.S.; Pinheiro, V.C.S. Predominance of Leishmania (Leishmania) amazonensis DNA in Lutzomyia longipalpis sandflies (Diptera: Psychodidae) from an endemic area for leishmaniasis in Northeastern Brazil. Rev. Inst. Med. Trop. São Paulo 2022, 64, e32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Killick-Kendrick, R. Phlebotomine vectors of the leishmaniases: A review. Med. Vet. Entomol. 1990, 4, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasil, Ministério da Saúde. Guia de Vigilância em Saúde; Ministério da Saúde: Brasília, Brasil, 2024; p. 456. Available online: https://www.gov.br/saude/pt-br/centrais-de-conteudo/publicacoes/svsa/vigilancia/guia-de-vigilancia-em-saude-volume-1-6a-edicao/view (accessed on 5 June 2023).

- Brazil, R.P. The dispersion of Lutzomyia longipalpis in urban areas. Rev. Soc. Bras. Med. Trop. 2013, 46, 263–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harhay, M.O.; Olliaro, P.L.; Costa, D.L.; Costa, C.H.N. Urban parasitology: Visceral leishmaniasis in Brazil. Trends Parasitol. 2011, 27, 403–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salomón, O.D.; Feliciangeli, M.D.; Quintana, M.G.; Afonso, M.M.S.; Rangel, E.F. Lutzomyia longipalpis urbanisation and control. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 2015, 110, 831–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Carvalho, M.R.; Valença, H.F.; da Silva, F.J.; de Pita-Pereira, D.; de Araújo-Pereira, T.; Britto, C.; Brazil, R.P.; Brandão-Filho, S.P. Natural Leishmania infantum infection in Migonemyia migonei (França, 1920) (Diptera: Psychodidae: Phlebotominae) the putative vector of visceral leishmaniasis in Pernambuco State, Brazil. Acta Trop. 2010, 116, 108–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvis-Ovallos, F.; Ueta, A.E.; Marques, G.O.; Sarmento, A.M.C.; Araujo, G.; Sandoval, C.; Tomokane, T.Y.; da Matta, V.L.R.; Laurenti, M.D.; Galati, E.A.B. Detection of Pintomyia fischeri (Diptera: Psychodidae) with Leishmania infantum (Trypanosomatida: Trypanosomatidae) Promastigotes in a Focus of Visceral Leishmaniasis in Brazil. J. Med. Entomol. 2021, 58, 830–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morelli, L.C.; de Pita-Pereira, D.; Britto, C.; de Araujo-Pereira, T.; de Souza, L.A.F.; Germano, K.O.; de Andrade, A.J.; Costa-Ribeiro, M.C.V. Leishmania (Leishmania) infantum DNA detection in Nyssomyia neivai in Vale do Ribeira, Paraná, Brazil. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 2024, 119, e230173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaves, A.F.D.C.P.; Costa, I.V.S.; Brito, M.O.D.; Sousa-Neto, F.A.D.; Mascarenhas, M.D.M. Leishmaniose visceral no Piauí, 2007-2019: Análise ecológica de séries temporais e distribuição espacial de indicadores epidemiológicos e operacionais. Epidemiol. Serv. Saúde 2022, 31, e2021339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, R.G.; Dawson, T.P. Predicting the impacts of climate change on the distribution of species: Are bioclimate envelope models useful? Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2003, 12, 361–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade-Filho, J.D.; da Silva, A.C.L.; Falcão, A.L. Phlebotomine sandflies in the State of Piauí, Brazil (Diptera: Psychodidae: Phlebotominae). Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 2001, 96, 1085–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sousa, R.L.T.; de Araujo-Pereira, T.; Leal, A.R.S.; Freire, S.M.; Silva, C.L.M.; Mallet, J.R.S.; Vilela, M.L.; Vasconcelos, S.A.; Gomes, R.; Teixeira, C.; et al. Association between the potential distribution of Lutzomyia longipalpis and Nyssomyia whitmani and leishmaniasis incidence in Piauí State, Brazil. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2023, 17, e0011388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo, A.B.F.; Werneck, G.L.; Cruz, M.S.P.; da Silva, J.P.; de Almeida, A.S. Land use, land cover, and prevalence of canine visceral leishmaniasis in Teresina, Piauí State, Brazil: An approach using orbital remote sensing. Cad. Saúde Pública 2017, 33, e00093516. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rangel, E.F.; Vilela, M.L. Lutzomyia longipalpis (Diptera, Psychodidae, Phlebotominae) and urbanization of visceral leishmaniasis in Brazil. Cad. Saúde Pública 2008, 24, 2948–2952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Almeida, A.S.; de Andrade-Medronho, R.; Werneck, G.L. Identification of Risk Areas for Visceral Leishmaniasis in Teresina, Piaui State, Brazil. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2011, 84, 681–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, N.P.; Almeida, A.B.P.F.; Freitas, T.P.T.; da Paz, R.C.R.; Dutra, V.; Nakazato, L.; Sousa, V.R.F. Leishmania (Leishmania) infantum chagasi in wild canids kept in captivity in the State of Mato Grosso. Rev. Soc. Bras. Med. Trop. 2010, 43, 333–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mestre, G.L.C.; Ribeiro, A.L.M.; Miyazaki, R.D.; Rodrigues, J.S.V.; Almeida, A.B.P.F.; Sousa, V.R.F.; Missawa, N.A. Phlebotomine sandflies and canine infection in areas of human visceral leishmaniasis, Cuiabá, Mato Grosso. Rev. Bras. Parasitol. Vet. 2011, 20, 228–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casaril, A.E.; Monaco, N.Z.N.; Oliveira, E.F.; Eguchi, G.U.; Filho, A.C.P.; Pereira, L.E.; Oshiro, E.T.; Galati, E.A.B.; Mateus, N.L.F.; de Oliveira, A.G. Spatiotemporal analysis of sandfly fauna (Diptera: Psychodidae) in an endemic area of visceral leishmaniasis at Pantanal, central South America. Parasites Vectors 2014, 7, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosário, I.N.G.; de Andrade, A.J.; Ligeiro, R.; Ishak, R.; Silva, I.M. Evaluating the Adaptation Process of Sandfly Fauna to Anthropized Environments in a Leishmaniasis Transmission Area in the Brazilian Amazon. J. Med. Entomol. 2017, 54, 450–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística IBGE. Piauí|Cidades e Estados|IBGE. Available online: https://www.ibge.gov.br/cidades-e-estados/pi.html (accessed on 22 February 2023).

- IBGE—Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. Divisão Regional do Brasil em Regiões Geográficas Imediatas e Regiões Geográficas Intermediárias, 81st ed.; de Geografia, C., Ed.; IBGE: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2017; p. 84. Available online: https://biblioteca.ibge.gov.br/index.php/biblioteca-catalogo?view=detalhes&id=2100600 (accessed on 17 March 2023).

- Medeiros, R.M.; Cavalcanti, E.P.; Duarte, J.F.M. Classificação Climática de Köppen para o Estado do Piauí—Brasil. Rev. Equador 2020, 9, 82–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBGE. Teresina (PI)|Cidades e Estados|IBGE. In Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística; IBGE: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Available online: https://www.ibge.gov.br/cidades-e-estados/pi/teresina.html (accessed on 22 February 2023).

- Lima, M.G.; Moraes, A.M.; Nunes, L.A.P.L.; Andrade Júnior, A.S. Distribuição Regional dos Climas. Classificação Climática de Köppen. In Climas do Piauí: Interações com o Ambiente, 1st ed.; Ribeiro, R.A., Ed.; EDUFPI: Teresina, Brasil, 2020; p. 31. Available online: https://ufpi.br/arquivos_download/arquivos/LIVRO_CLIMA_E_MEIO_AMBIENTE_220201020201106.pdf (accessed on 17 March 2023).

- Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística IBGE. Altos (PI)|Cidades e Estados|IBGE. Available online: https://www.ibge.gov.br/cidades-e-estados/pi/altos.html (accessed on 22 February 2023).

- Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística IBGE. Pedro II (PI)|Cidades e Estados|IBGE. Available online: https://www.ibge.gov.br/cidades-e-estados/pi/pedro-ii.html (accessed on 22 February 2023).

- Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística IBGE. Oeiras (PI)|Cidades e Estados|IBGE. Available online: https://www.ibge.gov.br/cidades-e-estados/pi/oeiras.html (accessed on 22 February 2023).

- Pugedo, H.; Barata, R.A.; França-Silva, J.C.; Silva, J.C.; Dias, E.S. HP: An improved model of suction light trap for the capture of small insects. Rev. Soc. Bras. Med. Trop. 2005, 38, 70–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forattini, O.P. Técnicas de Laboratório. In Entomologia Médica, 2nd ed.; Blucher, E., Ed.; Universidade de São Paulo: São Paulo, Brasil, 1973; Volume 4, pp. 634–635. [Google Scholar]

- Galati, E.A.B. Morfologia e terminologia de Phlebotominae (Diptera: Psychodidae). Classificação e identificação de táxons das Américas. In Apostila da Disciplina Bioecologia e Identificação de Phlebotominae do Programa de Pós-Graduação em Saúde Pública; Faculdade de Saúde Pública da Universidade de São Paulo: São Paulo, Brasil, 2024; Volume 1, p. 134. Available online: https://www.fsp.usp.br/egalati/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/Apostila-Vol.-1_2024.pdf (accessed on 17 March 2023).

- Marcondes, C.B. A Proposal of Generic and Subgeneric Abbreviations for Phlebotomine sandflies (Diptera: Psychodidae: Phlebotominae) of The World. Entomol. News 2007, 118, 351–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickham, H. ggplot2. WIREs Comput. Stat. 2011, 3, 180–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passos, V.M.; Lasmar, E.B.; Gontijo, C.M.; Fernandes, O.; Degrave, W. Natural infection of a domestic cat (Felis domesticus) with Leishmania (Viannia) in the metropolitan region of Belo Horizonte, state of Minas Gerais, Brazil. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 1996, 91, 19–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lins, R.M.; Oliveira, S.G.; Souza, N.A.; de Queiroz, R.G.; Justiniano, S.C.; Ward, R.D.; Kyriacou, C.P.; Peixoto, A.A. Molecular evolution of the cacophony IVS6 region in sandflies. Insect Mol. Biol. 2002, 11, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo-Pereira, T.; Pita-Pereira, D.; Boité, M.C.; Melo, M.; Costa-Rego, T.A.; Fuzari, A.A.; Brazil, R.P.; Britto, C. First description of Leishmania (Viannia) infection in Evandromyia saulensis, Pressatia sp. and Trichophoromyia auraensis (Psychodidae: Phlebotominae) in a transmission area of cutaneous leishmaniasis in Acre state, Amazon Basin, Brazil. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 2017, 112, 75–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Graça, G.C.; Volpini, A.C.; Romero, G.A.S.; Oliveira Neto, M.P.; Hueb, M.; Porrozzi, R.; Boité, M.C.; Cupolillo, E. Development and validation of PCR-based assays for diagnosis of American cutaneous leishmaniasis and identification of the parasite species. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 2012, 107, 664–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zampieri, R.A.; Laranjeira-Silva, M.F.; Muxel, S.M.; Lima, A.C.S.; Shaw, J.J.; Floeter-Winter, L.M. High Resolution Melting Analysis Targeting hsp70 as a Fast and Efficient Method for the Discrimination of Leishmania Species. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2016, 10, e0004485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitano, T.; Umetsu, K.; Tian, W.; Osawa, M. Two universal primer sets for species identification among vertebrates. Int. J. Leg. Med. 2007, 121, 423–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kearse, M.; Moir, R.; Wilson, A.; Stones-Havas, S.; Cheung, M.; Sturrock, S.; Buxton, S.; Cooper, A.; Markowitz, S.; Duran, C.; et al. Geneious Basic: An integrated and extendable desktop software platform for the organization and analysis of sequence data. Bioinformatics 2012, 28, 1647–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Schwartz, S.; Wagner, L.; Miller, W. A greedy algorithm for aligning DNA sequences. J. Comput. Biol. 2000, 7, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasconcelos, S.A.; de Sousa, R.L.T.; Costa Junior, E.; Diniz E Souza, J.P.; Cavalcante, D.; da Silva, A.C.L.; de Mendonça, I.L.; Mallet, J.; Teixeira, C.R.; Werneck, G.L.; et al. Characterisation of an area of coexistent visceral and cutaneous leishmaniasis transmission in the State of Piauí, Brazil. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 2024, 119, e230181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Costa, S.M.; Cordeiro, J.L.P.; Rangel, E.F. Environmental suitability for Lutzomyia (Nyssomyia) whitmani (Diptera: Psychodidae: Phlebotominae) and the occurrence of American cutaneous leishmaniasis in Brazil. Parasites Vectors 2018, 11, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moya, S.L.; Giuliani, M.G.; Acosta, M.M.; Salomón, O.D.; Liotta, D.J. First description of Migonemyia migonei (França) and Nyssomyia whitmani (Antunes & Coutinho) (Psychodidae: Phlebotominae) natural infected by Leishmania infantum in Argentina. Acta Trop. 2015, 152, 181–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, A.M.; Guirado, M.M.; Dibo, M.R.; Rodas, L.A.C.; Bocchi, M.R.; Chiaravalloti-Neto, F. Occurrence of Lutzomyia longipalpis and human and canine cases of visceral leishmaniasis and evaluation of their expansion in the Northwest region of the State of São Paulo, Brazil. Rev. Soc. Bras. Med. Trop. 2016, 49, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, A.M.; López, R.V.M.; Dibo, M.R.; Rodas, L.A.C.; Guirado, M.M.; Chiaravalloti-Neto, F. Dispersion of Lutzomyia longipalpis and expansion of visceral leishmaniasis in São Paulo State, Brazil: Identification of associated factors through survival analysis. Parasites Vectors 2018, 11, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Missawa, N.A.; Maciel, G.B.M.L.; Rodrigues, H. Distribuição geográfica de Lutzomyia (Nyssomyia) whitmani (Antunes & Coutinho, 1939) no Estado de Mato Grosso. Rev. Soc. Bras. Med. Trop. 2008, 41, 369–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebêlo, J.M.M. Frequência horária e sazonalidade de Lutzomyia longipalpis (Diptera: Psychodidae: Phlebotominae) na Ilha de São Luís, Maranhão, Brasil. Cad. Saúde Pública 2001, 17, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resende, M.C.; Camargo, M.C.V.; Vieira, J.R.M.; Nobi, R.C.A.; Porto, M.N.M.; Oliveira, C.D.L.; Pessanha, J.E.; Cunha, M.C.M.; Brandão, S.T. Seasonal variation of Lutzomyia longipalpis in Belo Horizonte, State of Minas Gerais. Rev. Soc. Bras. Med. Trop. 2006, 39, 51–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, R.D.; Hamilton, J.G.C.; Dougherty, M.; Falcao, A.L.; Feliciangeli, M.D.; Perez, J.E.; Veltkamp, C.J. Pheromone disseminating structures in tergites of male phlebotomines (Diptera: Psychodidae). Bull. Entomol. Res. 1993, 83, 437–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, D.W.; Dye, C. Pheromones, kairomones and the aggregation dynamics of the sandfly Lutzomyia longipalpis. Anim. Behav. 1997, 53, 721–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prudhomme, J.; Rahola, N.; Toty, C.; Cassan, C.; Roiz, D.; Vergnes, B.; Thierry, M.; Rioux, J.A.; Alten, B.; Sereno, D.; et al. Ecology and spatiotemporal dynamics of sandflies in the Mediterranean Languedoc region (Roquedur area, Gard, France). Parasites Vectors 2015, 8, 642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Añez, N.; Nieves, E.; Cazorla, D.; Oviedo, M.; Yarbuh, A.L.D.; Valera, M. Epidemiology of cutaneous leishmaniasis in Merida, Venezuela. III. Altitudinal distribution, age structure, natural infection and feeding behaviour of sandflies and their relation to the risk of transmission. Ann. Trop. Med. Parasitol. 1994, 88, 279–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dujardin, J.P.; Le Pont, F. Geographic variation of metric properties within the neotropical sandflies. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2004, 4, 353–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilela, M.L.; Freitas, S.P.C.; Paes, L.R.N.B.; Azevedo, C.G.; Carvalho, B.M.; Rangel, E.F. The Distribution and Bioecological Aspects of Sandflies (Diptera, Psychodidae) in the Municipality of Araguaína, State of Tocantins, Brazil. Int. J. Zoo. Anim. Biol. 2022, 5, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, I.S.; Santos, C.B.; Grimaldi, G., Jr.; Ferreira, A.L.; Falqueto, A. American visceral leishmaniasis dissociated from Lutzomyia longipalpis (Diptera, Psychodidae) in the State of Espírito Santo, Brazil. Cad. Saúde Pública 2010, 26, 365–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeWinter, S.; Shahin, K.; Fernandez-Prada, C.; Greer, A.L.; Weese, J.S.; Clow, K.M. Ecological determinants of leishmaniasis vector, Lutzomyia spp.: A scoping review. Med. Vet. Entomol. 2024, 38, 393–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araujo-Pereira, T.; Pita-Pereira, D.; Baia-Gomes, S.M.; Boité, M.; Silva, F.; Pinto, I.S.; de Sousa, R.L.T.; Fuzari, A.; de Souza, C.; Brazil, R.; et al. An overview of the sandfly fauna (Diptera: Psychodidae) followed by the detection of Leishmania DNA and blood meal identification in the state of Acre, Amazonian Brazil. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 2020, 115, e200157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moya, S.L.; Giuliani, M.G.; Santini, M.S.; Quintana, M.G.; Salomón, O.D.; Liotta, D.J. Leishmania infantum DNA detected in phlebotomine species from Puerto Iguazú City, Misiones province, Argentina. Acta Trop. 2017, 172, 122–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rêgo, F.D.; Souza, G.D.; Miranda, J.B.; Peixoto, L.V.; Andrade-Filho, J.D. Potential Vectors of Leishmania Parasites in a Recent Focus of Visceral Leishmaniasis in Neighborhoods of Porto Alegre, State of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil. J. Med. Entomol. 2020, 57, 1286–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, E.S.; Michalsky, É.M.; Nascimento, J.C.; Ferreira, E.C.; Lopes, J.V.; Fortes-Dias, C.L. Detection of Leishmania infantum, the etiological agent of visceral leishmaniasis, in Lutzomyia neivai, a putative vector of cutaneous leishmaniasis. J. Vector Ecol. 2013, 38, 193–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guimarães, V.C.F.V.; Pruzinova, K.; Sadlova, J.; Volfova, V.; Myskova, J.; Brandão Filho, S.P.; Volf, P. Lutzomyia migonei is a permissive vector competent for Leishmania infantum. Parasites Vectors 2016, 9, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Oliveira, E.F.; Silva, E.A.; Fernandes, C.E.S.; Paranhos Filho, A.C.; Gamarra, R.M.; Ribeiro, A.A.; Brazil, R.P.; Oliveira, A.G. Biotic factors and occurrence of Lutzomyia longipalpis in endemic area of visceral leishmaniasis, Mato Grosso do Sul, Brazil. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 2012, 107, 396–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, C.H.N. Characterization and speculations on the urbanization of visceral leishmaniasis in Brazil. Cad. Saúde Pública 2008, 24, 2959–2963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werneck, G.L. Forum: Geographic spread and urbanization of visceral leishmaniasis in Brazil. Introd. Cad. Saúde Pública 2008, 24, 2937–2940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lainson, R.; Rangel, E.F. Lutzomyia longipalpis and the eco-epidemiology of American visceral leishmaniasis, with particular reference to Brazil: A review. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 2005, 100, 811–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dantas-Torres, F. The role of dogs as reservoirs of Leishmania parasites, with emphasis on Leishmania (Leishmania) infantum and Leishmania (Viannia) braziliensis. Vet. Parasitol. 2007, 149, 139–146. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira-Pereira, Y.N.; Moraes, J.L.P.; Lorosa, E.S.; Rebêlo, J.M.M. Preferência alimentar sanguínea de flebotomíneos da Amazônia do Maranhão, Brasil. Cad. Saúde Pública 2008, 24, 2183–2186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Missawa, N.A.; Lorosa, E.S.; Dias, E.S. Preferência alimentar de Lutzomyia longipalpis (Lutz & Neiva, 1912) em área de transmissão de leishmaniose visceral em Mato Grosso. Rev. Soc. Bras. Med. Trop. 2008, 41, 365–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Species | Teresina | Altos | Pedro II | Oeiras | Total Number | Abundance (%) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intra | Peri | T.Tr | Total | Peri | Total | Intra | Peri | Total | Peri | Total | |||

| Lu. longipalpis | 527 | 3281 | 70 | 3878 | 589 | 589 | 135 | 902 | 1037 | 117 | 117 | 5621 | 54.87 |

| Ny. whitmani | 17 | 20 | 37 | 27 | 27 | 228 | 2822 | 3050 | 2 | 2 | 3116 | 30.41 | |

| Mi. migonei | 789 | 789 | 789 | 7.70 | |||||||||

| Ny. intermedia | 2 | 519 | 521 | 521 | 5.09 | ||||||||

| Ev. carmelinoi | 1 | 7 | 1 | 9 | 11 | 45 | 56 | 67 | 67 | 132 | 1.29 | ||

| Sc. sordellii | 1 | 1 | 59 | 59 | 60 | 0.59 | |||||||

| Ev. lenti | 3 | 3 | 3 | 0.03 | |||||||||

| Ev. termitophila | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0.02 | |||||||||

| Br. avellari | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.01 | |||||||||

| TOTAL | 546 | 3309 | 71 | 3926 * | 616 | 616 | 376 | 5136 | 5512 * | 191 | 191 | 10,245 | 100.00 |

| Municipalities | Sandflies | Climate Data | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rainfall—mm (p-Value) | Temp—°C (p-Value) | R.H—% (p-Value) | ||

| Teresina | Lu. longipalpis | −0.39 (0.25) | 0.35 (0.26) | −0.45 (0.13) |

| Ny. whitmani | −0.78 (<0.01 *) | 0.63 (0.02 *) | −0.80 (<0.02 *) | |

| Total sandflies | −0.36 (0.25) | 0.35 (0.26) | −0.45 (0.26) | |

| Pedro II | Lu. longipalpis | 0.17 (0.55) | −0.14 (0.62) | −0.34 (0.23) |

| Ny. whitmani | 0.11 (0.71) | 0.26 (0.36) | −0.52 (0.03 *) | |

| Ny. intermedia | 0.41 (0.14) | −0.31 (0.27) | −0.12 (0.68) | |

| Mi. migonei | 0.26 (0.36) | −0.17 (0.55) | −0.03 (0.90) | |

| ACL Vectors | 0.58 (0.02 *) | −0.02 (0.95) | −0.17 (0.55) | |

| Total sandflies | 0.42 (0.13) | 0.06 (0.82) | −0.32 (0.90) | |

| Species | Correlated Variable | Correlation (ρ) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lu. longipalpis | Altitude | 0.03 | 0.36 |

| Ny. whitmani | Altitude | 0.22 | <0.01 * |

| Total of both species | Altitude | 0.76 | 0.02 * |

| Mun. | Zone | N/L | Sandfly | Parasite sp. (hsp70) | Accession Number | BLAST Analysis | Positive Pool/Insects | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E-V | ID (%) | |||||||

| THE | Urb | Angelim | Lu. longipalpis | L. (V.) braziliensis | MN395479.1 | 2E-51 | 100.0 | 1/9 |

| OEI | Rur | Queiroz | Lu. longipalpis | L. (V.) braziliensis | MN395479.1 | 9E-49 | 98.3 | 1/7 |

| PII | Rur | P. Ferreiras | Ny. whitmani | L. (V.) braziliensis | MN395479.1 | 4E-67 | 100.0 | 1/10 |

| L. (L.) infantum | MF137828.1 | 3E-63 | 98.6 | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

de Sousa, R.L.T.; Araujo-Pereira, T.; Vasconcelos, S.A.; Freire, S.M.; Lima, O.B.; dos Santos-Mallet, J.R.; Vilela, M.L.; Vasconcelos, V.M.d.S.; de Andrade, E.B.; Gomes, R.; et al. Ecological Perspectives on Leishmaniasis Parasitism Patterns: Evidence of Possible Alternative Vectors for Leishmania (Leishmania) infantum (syn. L. chagasi) and Leishmania (Viannia) braziliensis in Piauí, Brazil. Pathogens 2025, 14, 930. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14090930

de Sousa RLT, Araujo-Pereira T, Vasconcelos SA, Freire SM, Lima OB, dos Santos-Mallet JR, Vilela ML, Vasconcelos VMdS, de Andrade EB, Gomes R, et al. Ecological Perspectives on Leishmaniasis Parasitism Patterns: Evidence of Possible Alternative Vectors for Leishmania (Leishmania) infantum (syn. L. chagasi) and Leishmania (Viannia) braziliensis in Piauí, Brazil. Pathogens. 2025; 14(9):930. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14090930

Chicago/Turabian Stylede Sousa, Raimundo Leoberto Torres, Thais Araujo-Pereira, Silvia Alcântara Vasconcelos, Simone Mousinho Freire, Oriana Bezerra Lima, Jacenir Reis dos Santos-Mallet, Mauricío Luiz Vilela, Victor Manoel de Sousa Vasconcelos, Etielle Barroso de Andrade, Régis Gomes, and et al. 2025. "Ecological Perspectives on Leishmaniasis Parasitism Patterns: Evidence of Possible Alternative Vectors for Leishmania (Leishmania) infantum (syn. L. chagasi) and Leishmania (Viannia) braziliensis in Piauí, Brazil" Pathogens 14, no. 9: 930. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14090930

APA Stylede Sousa, R. L. T., Araujo-Pereira, T., Vasconcelos, S. A., Freire, S. M., Lima, O. B., dos Santos-Mallet, J. R., Vilela, M. L., Vasconcelos, V. M. d. S., de Andrade, E. B., Gomes, R., Teixeira, C., Carvalho, B. M., Pita-Pereira, D., & Britto, C. (2025). Ecological Perspectives on Leishmaniasis Parasitism Patterns: Evidence of Possible Alternative Vectors for Leishmania (Leishmania) infantum (syn. L. chagasi) and Leishmania (Viannia) braziliensis in Piauí, Brazil. Pathogens, 14(9), 930. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14090930