First Molecular Detection of Orthohantaviruses (Orthohantavirus hantanense and O. jejuense) in Trombiculid Mites from Wild Rodents in the Republic of Korea

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics Statement

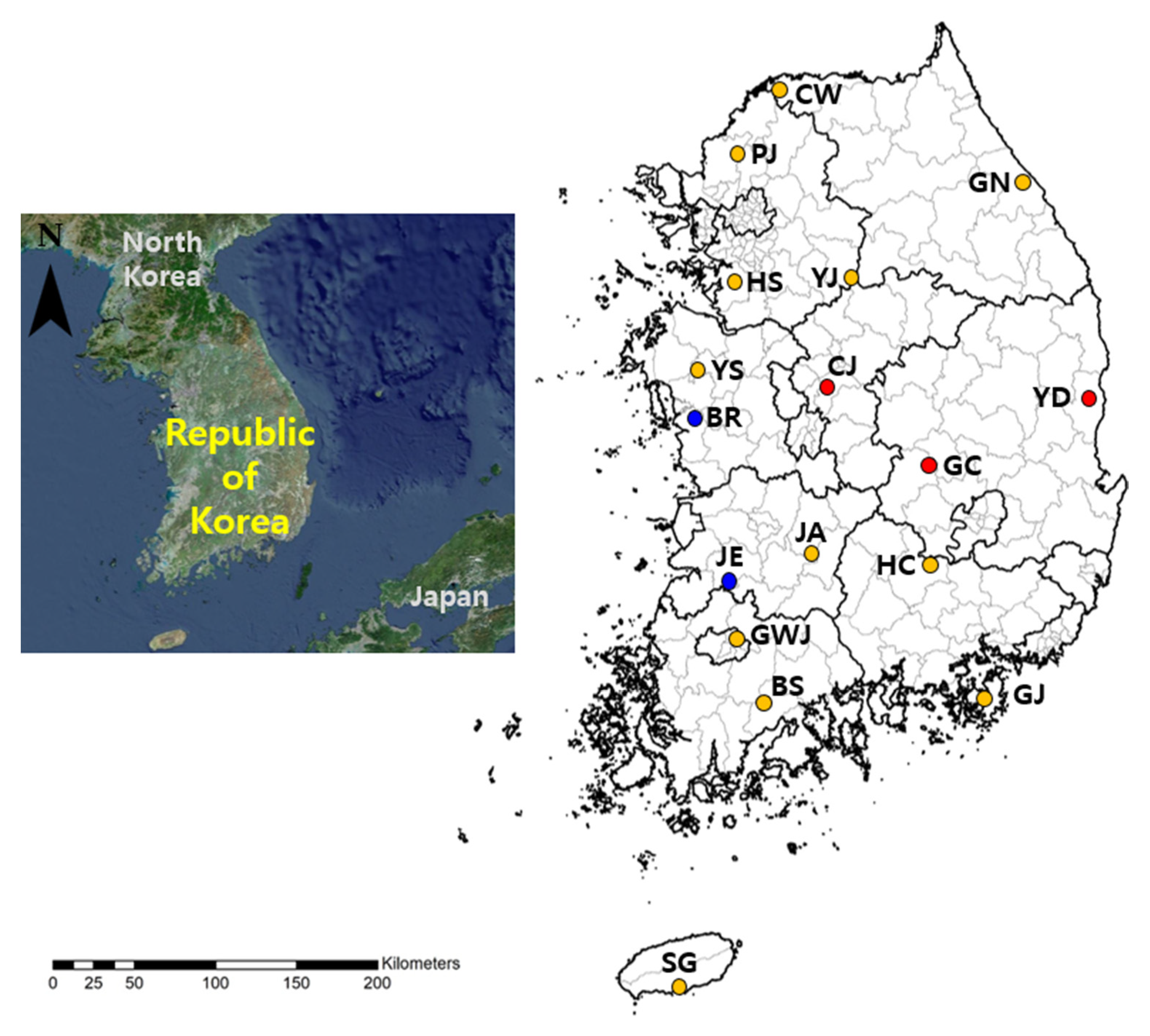

2.2. Rodent Trapping and Trombiculid Mite Sampling

2.3. RNA Extraction and Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) Amplification

2.4. Molecular Identification of Rodents and Ticks

2.5. Sequencing and Phylogenetic Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Trombiculid Mite Collection and Orthohantavirus Minimum Infection Rate (MIR)

3.2. Orthohantavirus Detection in Host Rodents and Other Ectoparasites

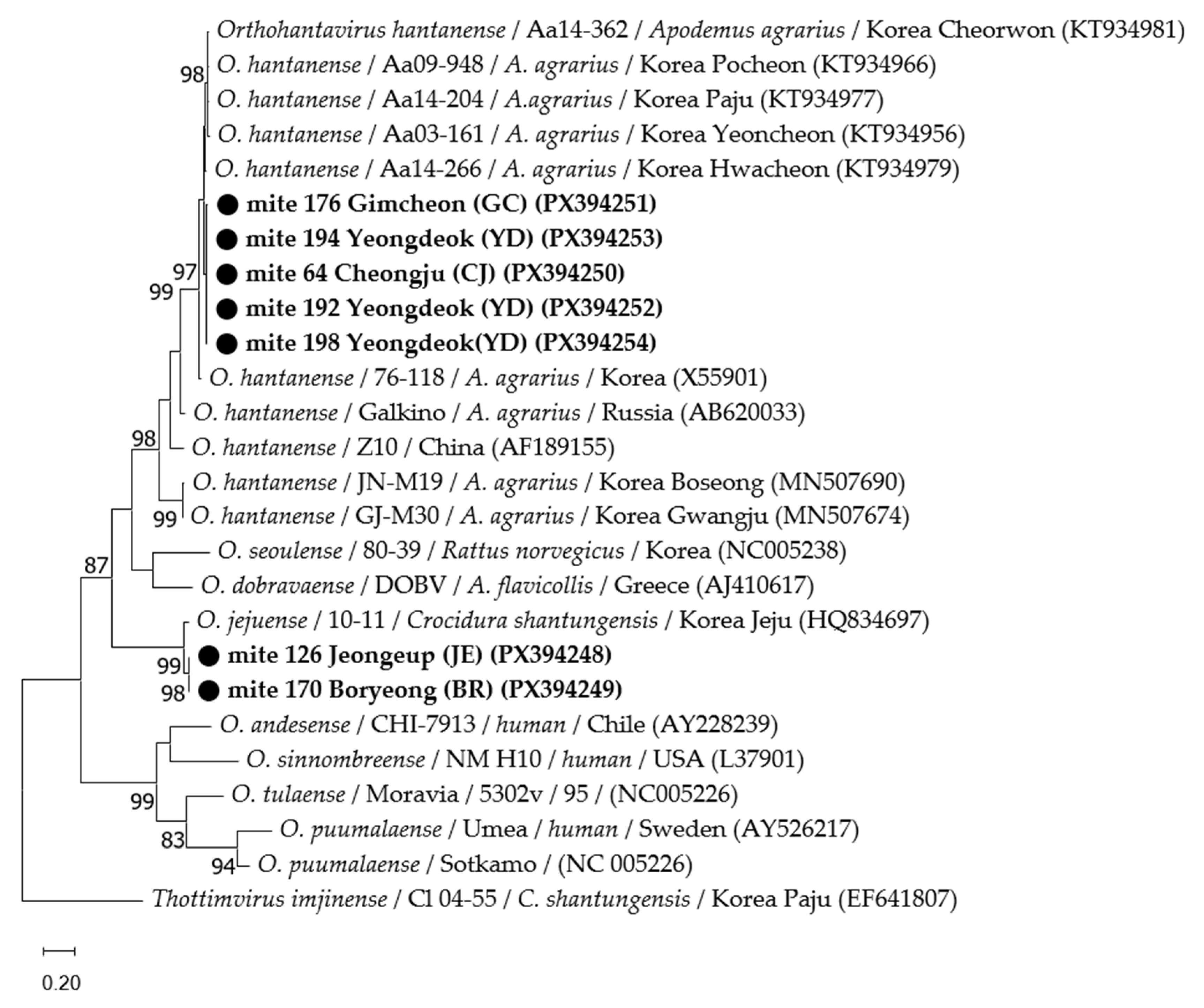

3.3. Phylogenetic Analyses

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HPS | hantavirus pulmonary syndrome |

| SFTS | severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome |

| qPCR | quantitative polymerase chain reaction |

| ROK | Republic of Korea |

| HFRS | hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome |

| MIR | minimum infection rate |

References

- Kuhn, J.H.; Schmaljohn, C.S. A brief history of bunyaviral family Hantaviridae. Diseases 2023, 11, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noack, D.; Goeijenbier, M.; Reusken, C.B.E.M.; Koopmans, M.P.G.; Rockx, B.H.G. Orthohantavirus pathogenesis and cell tropism. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2020, 10, 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laine, O.; Joutsi-Korhonen, L.; Lassila, R.; Koski, T.; Huhtala, H.; Vaheri, A.; Mäkelä, S.; Mustonen, J. Hantavirus infection-induced thrombocytopenia triggers increased production but associates with impaired aggregation of platelets except for collagen. Thromb. Res. 2015, 136, 1126–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanagihara, R.; Gu, S.H.; Arai, S.; Kang, H.J.; Song, J.W. Hantaviruses: Rediscovery and new beginnings. Virus Res. 2014, 187, 6–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryou, J.; Lee, H.I.; Yoo, Y.J.; Noh, Y.T.; Yun, S.M.; Kim, S.Y.; Shin, E.H.; Han, M.G.; Ju, Y.R. Prevalence of hantavirus infection in wild rodents from five provinces in Korea, 2007. J. Wildl. Dis. 2011, 47, 427–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency. The Annual Statistics. 2025. Available online: https://dportal.kdca.go.kr/pot/is/inftnsdsEDW.do (accessed on 13 September 2025).

- Baek, L.J.; Kariwa, H.; Lokugamage, K.; Yoshimatsu, K.; Arikawa, J.; Takashima, I.; Kang, J.I.; Moon, S.S.; Chung, S.Y.; Kim, E.J.; et al. Soochong virus: An antigenically and genetically distinct hantavirus isolated from Apodemus peninsulae in Korea. J. Med Virol. 2006, 78, 290–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, M.H.; Kim, C.M.; Kim, D.M.; Yun, N.R.; Park, J.W.; Chung, J.K. Emerging hantavirus infection in wild rodents captured in suburbs of Gwangju Metropolitan City, South Korea. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2022, 16, e0010526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.W.; Lee, P.W.; Johnson, K.M. Isolation of the etiologic agent of Korean hemorrhagic fever. J. Infect. Dis. 1978, 137, 298–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.W.; Baek, L.J.; Johnson, K.M. Isolation of Hantaan virus, the etiologic agent of Korean hemorrhagic fever, from wild urban rats. J. Infect. Dis. 1982, 146, 638–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, K.-J.; Baek, L.J.; Moon, S.; Ha, S.J.; Kim, S.H.; Park, K.S.; Klein, T.A.; Sames, W.; Kim, H.-C.; Lee, J.S.; et al. Muju virus, a novel hantavirus harboured by the arvicolid rodent Myodes regulus in Korea. J. Gen. Virol. 2007, 88, 3121–3129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.-W.; Kang, H.J.; Gu, S.H.; Moon, S.S.; Bennett, S.N.; Song, K.-J.; Baek, L.J.; Kim, H.-C.; O’Guinn, M.L.; Chong, S.-T.; et al. Characterization of Imjin virus, a newly isolated hantavirus from the Ussuri white-toothed shrew (Crocidura lasiura). J. Virol. 2009, 83, 6184–6191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arai, S.; Gu, S.H.; Baek, L.J.; Tabara, K.; Bennett, S.N.; Oh, H.S.; Takada, N.; Kang, H.J.; Tanaka-Taya, K.; Morikawa, S.; et al. Divergent ancestral lineages of newfound hantaviruses harbored by phylogenetically related crocidurine shrew species in Korea. Virology 2012, 424, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.-T.; Park, C.-H.; Cho, K.-B.; Yoon, J.-J. Study of Exoparasites, Rickettsia and Hantaan virus in Bats. J. Korean Soc. Virol. 1998, 28, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Seo, M.-G.; Song, B.-G.; Kim, T.-K.; Noh, B.-E.; Lee, H.S.; Lee, W.-G.; Lee, H.I. Nationwide incidence of chigger mite populations and molecular detection of Orientia tsutsugamushi in the Republic of Korea, 2020. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santibáñez, P.; Palomar, A.M.; Portillo, A.; Santibáñez, S.; Oteo, J.A. The role of chiggers as human pathogens. Overv. Trop. Dis. 2015, 1, 173–202. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, F.; Wang, L.; Wang, S.; Zhu, L.; Dong, L.; Zhang, Z.; Hao, B.; Yang, F.; Liu, W.; Deng, Y.; et al. Meteorological factors affect the epidemiology of hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome via altering the breeding and hantavirus-carrying states of rodents and mites: A 9 years’ longitudinal study. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2017, 6, e104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houck, M.A.; Qin, H.; Roberts, H.R. Hantavirus transmission: Potential role of ectoparasites. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2001, 1, 75–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.B. Taxonomic Notes and Data Matrix for Interactive Key of Erinaceomorpha, Soricomorpha, and Rodentia (Mammalia) in Korea. Master’s Thesis, Incheon National University, Incheon, Republic of Korea, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H.I.; Shim, S.K.; Song, B.G.; Choi, E.N.; Hwang, K.J.; Park, M.Y.; Park, C.; Shin, E.H. Detection of Orientia tsutsugamushi, the causative agent of scrub typhus, in a novel mite species, Eushoengastia koreaensis, in Korea. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2011, 11, 209–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguti, N.; Tipton, V.J.; Keegan, H.L.; Toshioka, S. Ticks of Japan, Korea, and the Ryukyu islands. Brigh. Young Univ. Sci. Bull. Biol. Ser. 1971, 15, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.-C.; Kim, W.-K.; Klein, T.A.; Chong, S.-T.; Nunn, P.V.; Kim, J.-A.; Lee, S.-H.; No, J.S.; Song, J.-W. Hantavirus surveillance and genetic diversity targeting small mammals at Camp Humphreys, a US military installation and new expansion site, Republic of Korea. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0176514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kikuchi, F.; Aoki, K.; Ohdachi, S.D.; Tsuchiya, K.; Motokawa, M.; Jogahara, T.; Sơn, N.T.; Bawm, S.; Lin, K.S.; Thwe, T.L.; et al. Genetic diversity and phylogeography of Thottapalayam thottimvirus (Hantaviridae) in Asian house shrew (Suncus murinus) in Eurasia. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2020, 10, 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folmer, O.; Black, M.; Hoeh, W.; Lutz, R.; Vrijenhoek, R. DNA primers for amplification of mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I from diverse metazoan invertebrates. Mol. Mar. Biol. Biotechnol. 1994, 3, 294–299. [Google Scholar]

- Seo, M.-G.; Noh, B.-E.; Lee, H.S.; Kim, T.-K.; Song, B.-G.; Lee, H.I. Nationwide temporal and geographical distribution of tick populations and phylogenetic analysis of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus in ticks in Korea, 2020. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, L.-M.; Zhao, L.; Wen, H.-L.; Zhang, Z.-T.; Liu, J.-W.; Fang, L.-Z.; Xue, Z.-F.; Ma, D.-Q.; Zhang, X.-S.; Ding, S.-J.; et al. Haemaphysalis longicornis ticks as reservoir and vector of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus in China. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2015, 21, 1770–1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, S.D.; Hildreth, S.W.; Beaty, B.J. Estimation of infection rates in population of organisms using pools of variable size. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1980, 112, 124–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, M.; Misumii, H.; Gokuden, M.; Kadosaka, T.; Kuriyama, T.; Hiroko, S.A.T.; Fujita, H.; Yamamoto, S. Absorption of host hemolytic fluid by trombiculid mites (Acari: Trom biculidae). Annu. Rep. Ohara Gen. Hosp. 2013, 53, 21–32. [Google Scholar]

- Shatrov, A.B.; Kazakov, D.V.; Antonovskaia, A.A.; Gorobeyko, U.V. Morphological characterization of stylostome and skin reaction produced by Leptotrombidium album (Acariformes, Trombiculidae) on the bat Barbastella pacifica from Kunashir Island. Syst. Appl. Acarol. 2022, 27, 1970–1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Region | No. of Collected Rodents | No. of Collected Mites | No. of Tested Mites | No. of Tested Pools | No. of Positive Pools | MIR (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cheorwon | 10 | 605 | 230 | 27 | 0 | 0 |

| Paju | 2 | 246 | 91 | 10 | 0 | 0 |

| Gangneung | 10 | 186 | 65 | 12 | 0 | 0 |

| Hwaseong | 2 | 242 | 119 | 13 | 0 | 0 |

| Yeoju | 6 | 718 | 115 | 14 | 0 | 0 |

| Yesan | 3 | 141 | 61 | 7 | 0 | 0 |

| Cheongju | 13 | 781 | 229 | 29 | 1 | 0.4 |

| Boryeong | 6 | 26 | 13 | 3 | 1 | 7.7 |

| Yeongdeok | 8 | 349 | 113 | 14 | 3 | 2.7 |

| Gimcheon | 5 | 366 | 147 | 16 | 1 | 0.7 |

| Jinan | 8 | 126 | 40 | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| Jeongeup | 5 | 281 | 94 | 11 | 1 | 1.1 |

| Hapcheon | 6 | 291 | 125 | 14 | 0 | 0 |

| Gwangju | 5 | 120 | 23 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Boseong | 5 | 61 | 9 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Geoje | 5 | 374 | 169 | 18 | 0 | 0 |

| Seogwipo | 29 | 50 | 17 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 128 | 4963 | 1660 | 204 | 7 | 0.4 |

| Species | No. of Collected Rodents | No. of Rodents with HP Mite Pools | No. of HP Rodents with HP Mite Pools | No. of Ectoparasites from Rodents with HP Mite Pools | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ixodes nipponensis | Mesostigmata spp. | Pulicidae spp. | Anoplura spp. | Total | ||||

| Apodemus agrarius | 118 | 6 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Craseomys regulus | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Crocidura spp. | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, S.Y.; Lee, H.S.; Yoon, H.; Lee, H.I. First Molecular Detection of Orthohantaviruses (Orthohantavirus hantanense and O. jejuense) in Trombiculid Mites from Wild Rodents in the Republic of Korea. Pathogens 2025, 14, 1260. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121260

Kim SY, Lee HS, Yoon H, Lee HI. First Molecular Detection of Orthohantaviruses (Orthohantavirus hantanense and O. jejuense) in Trombiculid Mites from Wild Rodents in the Republic of Korea. Pathogens. 2025; 14(12):1260. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121260

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Seong Yoon, Hak Seon Lee, Hyunyoung Yoon, and Hee Il Lee. 2025. "First Molecular Detection of Orthohantaviruses (Orthohantavirus hantanense and O. jejuense) in Trombiculid Mites from Wild Rodents in the Republic of Korea" Pathogens 14, no. 12: 1260. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121260

APA StyleKim, S. Y., Lee, H. S., Yoon, H., & Lee, H. I. (2025). First Molecular Detection of Orthohantaviruses (Orthohantavirus hantanense and O. jejuense) in Trombiculid Mites from Wild Rodents in the Republic of Korea. Pathogens, 14(12), 1260. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121260