Grafting Tomato Scions on Root Knot Nematode (RKN)-Resistant Brinjal Rootstocks Complemented with Biocontrol Agents as an Integrated Nematode Management (INM) Strategy for the Development of RKN-Resistant Tomato

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Root Knot Nematode Screening Experiment

2.1.1. Root Knot Nematode Culture

2.1.2. Eggplant Varieties/Accessions and Potting Mixture

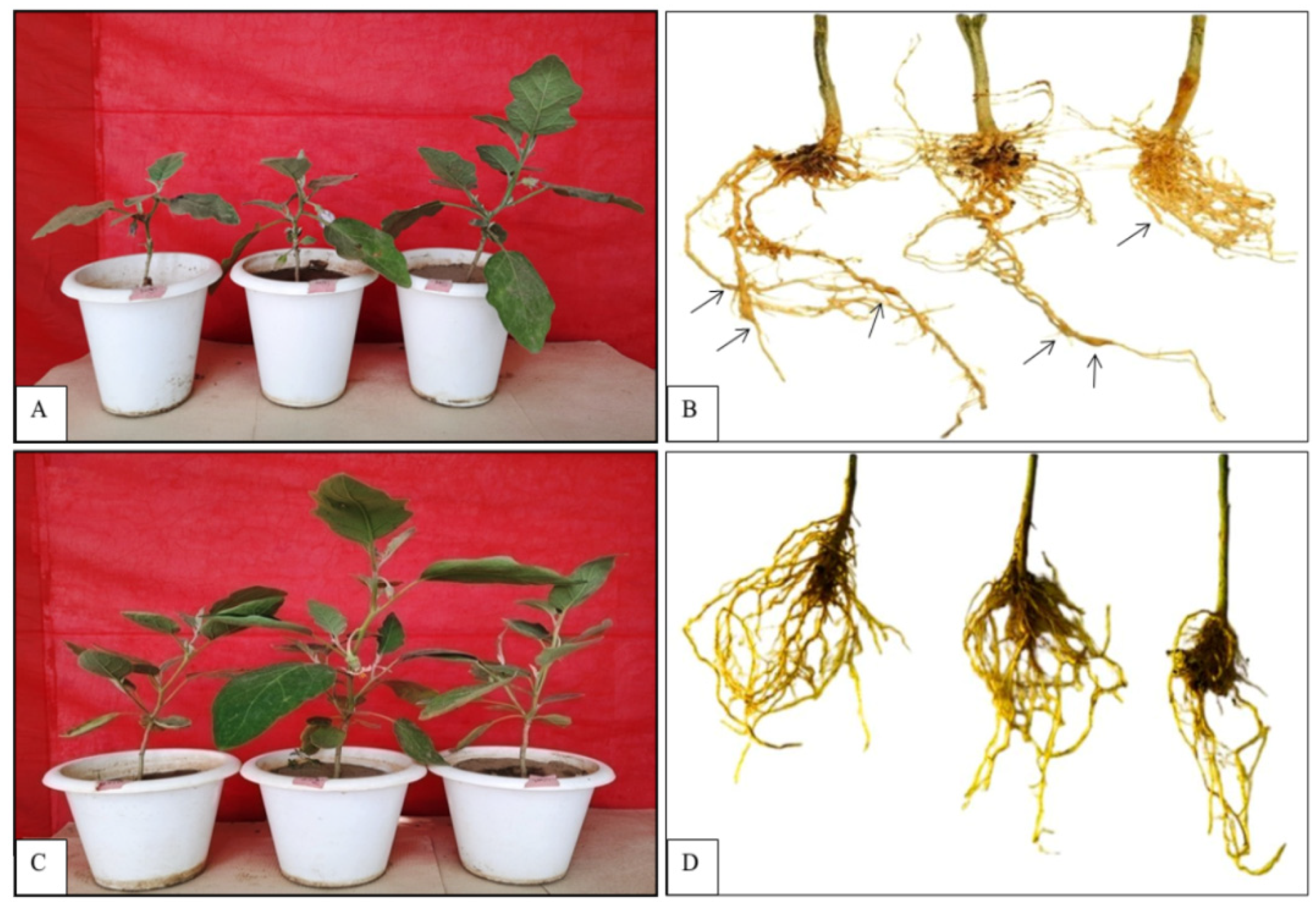

2.1.3. Physical Screening of Eggplant Genotypes for Root Knot Nematode Infection

2.1.4. Number of Galls and Egg Masses

2.1.5. Total Phenolic Content in Roots

2.2. Molecular Screening of Eggplant Varieties/Accessions

2.2.1. DNA Isolation

2.2.2. PCR Amplification

2.2.3. Grafting

2.2.4. Application of Biocontrol Agents to Enhance Meloidogyne incognita Resistance of Stably Grafted Tomato Plants

2.2.5. Estimation of RKN Population in 200 mL Soil Samples

2.2.6. Experimental Design and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

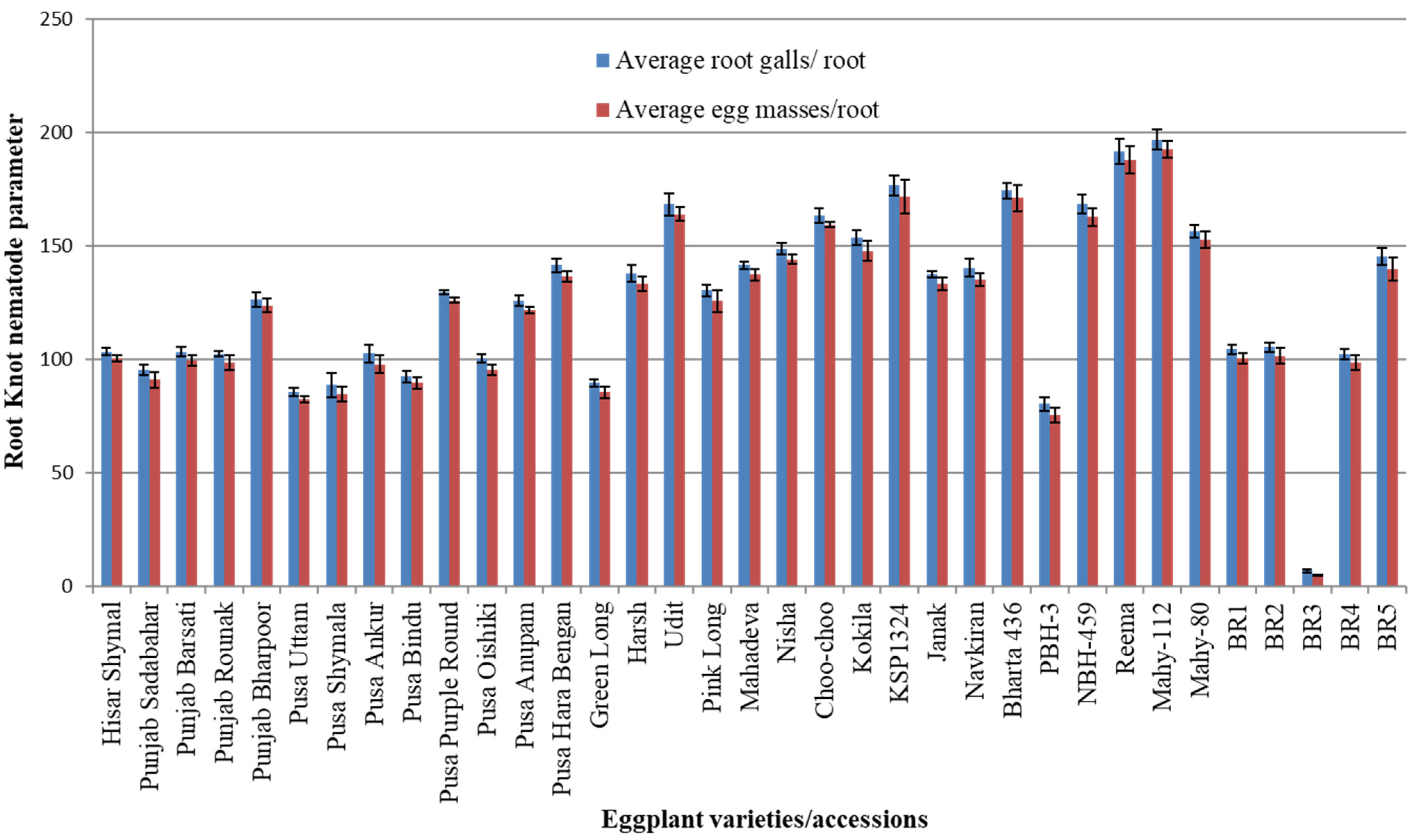

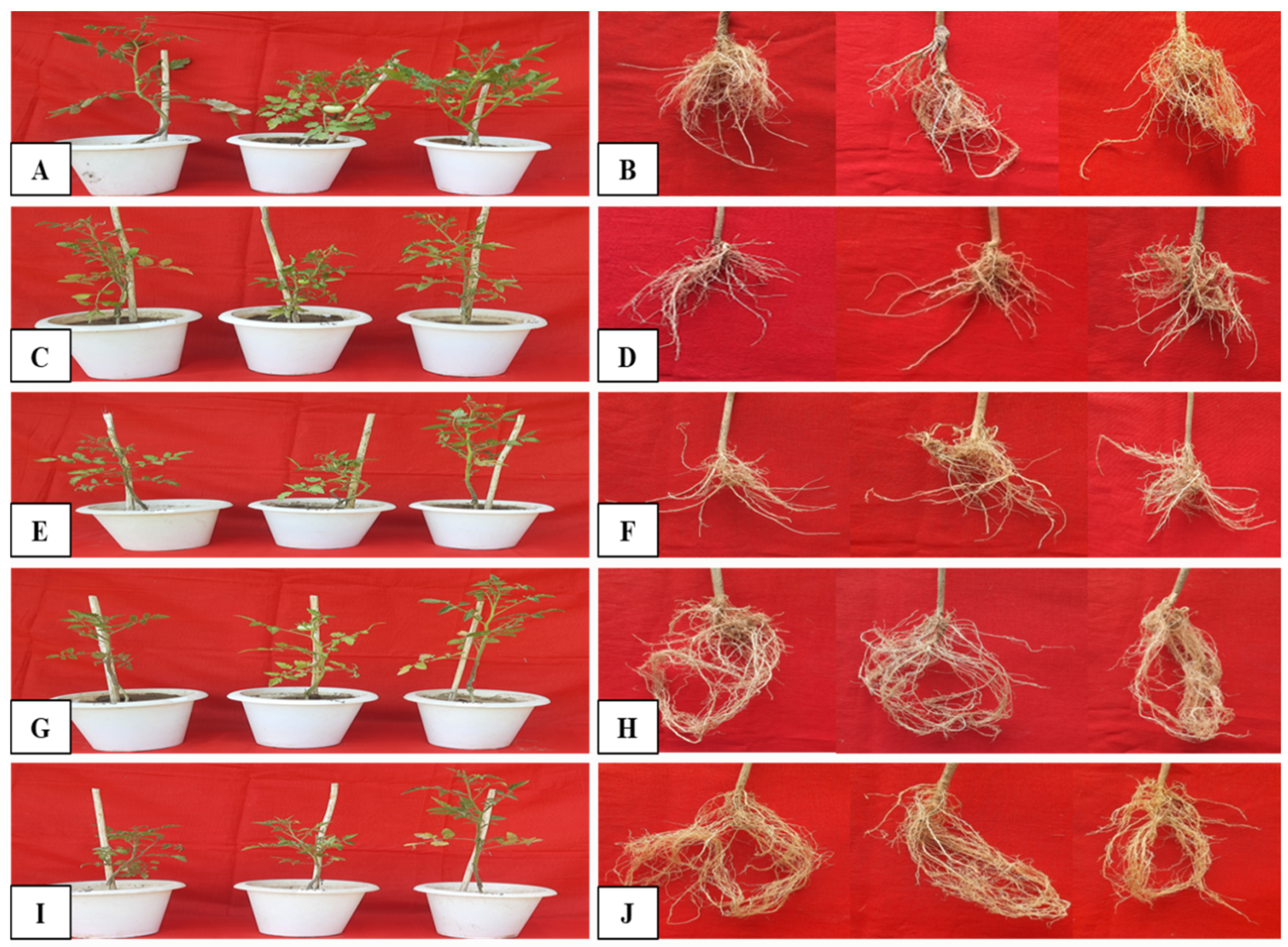

3.1. Screening of Eggplant Varieties/Accessions Against RKNs

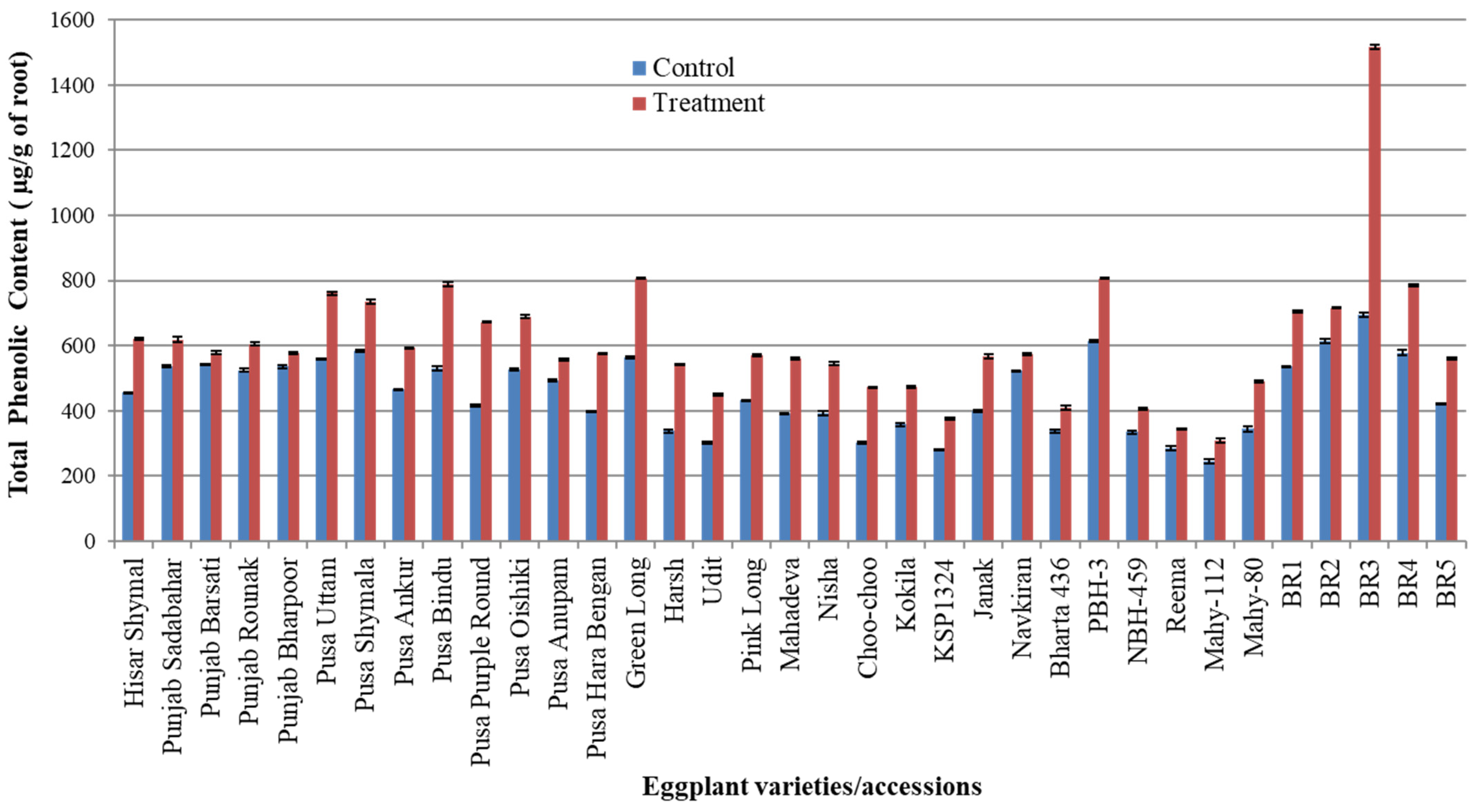

3.2. Total Phenolic Content (TPC) in Roots

3.3. Molecular Screening of Eggplant Varieties/Accessions

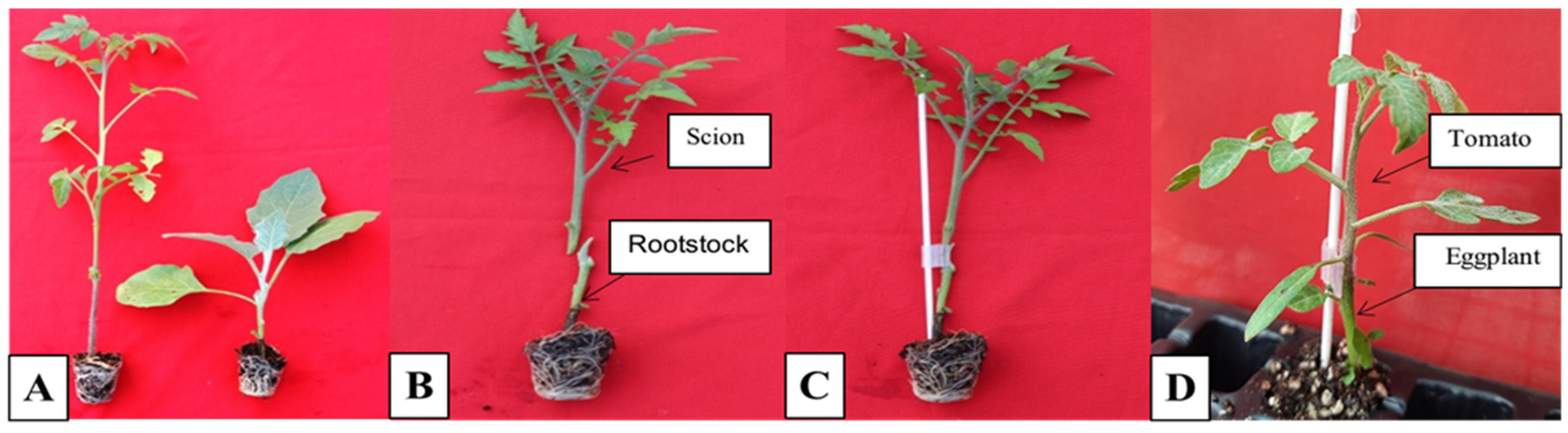

3.4. Grafting of Tomato on RKN-Resistant Eggplant Rootstocks

3.5. Application of Biocontrol Agents to Enhance the Resistance Against RKNs

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jones, J.T.; Haegeman, A.; Danchin, E.G.J.; Gaur, H.S.; Helder, J.; Jones, M.G.K.; Kikuchi, T.; Rose, M.L.; Palomares-Rius, J.E.; Wesemale, W.M.L.; et al. Review of top 10 plant parasitic nematodes in molecular plant pathology. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2013, 14, 946–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gowda, M.T.; Sellaperumal, C.; Rai, A.B.; Singh, B. Root knot nematodes menace in vegetable crops and their management in India: A review. Veg. Sci. 2019, 46, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gai, Y.; Wang, H. Plant disease: A growing threat to global food security. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasser, J.N. Root-knot nematodes: A global menace to crop production. Plant Dis. 1980, 64, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikora, R.A.; Fernandez, E. Nematode parasites of vegetables. In Plant-Parasitic Nematodes in Subtropical and Tropical Agriculture; Luc, M., Sikora, R.A., Bridge, J., Eds.; CABI Publishing: Wallingford, UK, 2005; pp. 319–392. [Google Scholar]

- Coyne, D.L.; Fourie, H.H.; Moens, M. Current and future management strategies in resource-poor farming. In Root-Knot Nematodes; Perry, R.N., Moens, M., Starr, J.L., Eds.; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2009; pp. 444–475. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, R.; Kumar, U. Assessment of nematode distribution and yield losses in vegetable crops of western Uttar Pradesh in India. Int. J. Sci. Res. 2015, 438, 2812–2816. [Google Scholar]

- Seid, A.; Fininsa, C.; Mekete, T.; Decraemer, W.; Wesemael, W.M.L. Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) and root-knot nematodes (Meloidogyne spp.)—A century-old battle. Nematology 2015, 17, 995–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, P.A. UC IPM Pest Management Guidelines: Tomato. UC ANR Publication 3470. 2008. Available online: https://www.ipm.ucdavis.edu (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Chandan, K.Y.; Palande, P.R.; Walunj, A.R.; Pawar, B.Y.; Patil, M.R. Assessment of avoidable yield losses due to root-knot nematode, Meloidogyne incognita, infesting tomato. Pharma Innov. 2022, 11, 2701–2703. [Google Scholar]

- Rashid, M.H.; Al-Mamun, M.H.; Uddin, M.N. How durable is root-knot nematode resistance in tomato? Plant Breed. Biotechnol. 2017, 5, 143–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boiteux, L.S.; Charchar, J.M. Genetic resistance to root-knot nematode (Meloidogyne javanica) in eggplant (Solanum melongena). Plant Breed. 1996, 115, 198–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhter, G.; Khan, T.A. Response of brinjal (Solanum melongena L.) varieties for resistance against root-knot nematode, Meloidogyne incognita race-1. J. Phytopharmacol. 2018, 7, 222–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ates, A.C.; Fidan, H.; Ozarslandan, A.; Ata, A. Determination of the resistance of certain eggplant lines against Fusarium wilt, Potato Y potyvirus and root-knot nematode using molecular and classic methods. Fresenius Environ. Bull. 2018, 27, 7446–7453. [Google Scholar]

- Namisy, A.; Chen, J.R.; Prohens, J.; Metwally, E.; Elmahrouk, M.; Rakha, M. Screening of cultivated eggplant and wild relatives for resistance to bacterial wilt (Ralstonia solanacearum). Agriculture 2019, 9, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagnaresi, P.; Sala, T.; Irdani, T.; Scotto, C.; Lamontanara, A.; Beretta, M.; Rotino, G.L.; Sestili, S.; Cattivelli, L.; Sabatini, E. Solanum torvum responses to the root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita. BMC Genom. 2013, 14, 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, X.; Liu, J.; Bao, S.; Yang, Y.; Zhuang, Y. Molecular cloning and characterization of a wild eggplant Solanum aculeatissimum NBS-LRR gene involved in plant resistance to Meloidogyne incognita. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Bao, S.; Liu, J.; Yang, Y.; Zhuang, Y. Detect Molecular Labeling and Primer and the Application of the Western Eggplant Root-Knot Nematode Resistant SacMi Genes. Patent CN107287343A, 22 August 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Seah, S.; Williamson, V.M.; Garcia, B.E.; Mejia, L.; Salus, M.S.; Martin, C.T.; Maxwell, D.P. Evaluation of a co-dominant SCAR marker for detection of the Mi-1 locus for resistance to root-knot nematode in tomato germplasm. Rep. Tomato Genet. Coop. 2007, 57, 37–40. [Google Scholar]

- Maurya, D.; Mukherjee, A.; Bhagyashree; Sangam, S.; Kumar, R.; Akhtar, S.; Chattopadhyay, T. Marker-assisted stacking of Ty3, Mi1.2 and Ph3 resistance alleles for leaf curl, root knot and late blight diseases in tomato. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2023, 29, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhagat, Y.S.; Bhat, R.S.; Kolekar, R.M.; Patil, A.C.S.; Patil, L.R.V.; Udikeri, S.S. Remusatia vivipara lectin and Sclerotium rolfsii lectin interfere with the development and gall formation activity of Meloidogyne incognita in transgenic tomato. Transgenic Res. 2019, 28, 299–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussey, R.S.; Janssen, G.J.W. Root-knot nematodes: Meloidogyne species. In Plant Resistance to Parasitic Nematodes; Starr, J.L., Cook, R., Bridge, J., Eds.; CAB International: Wallingford, UK, 2002; pp. 43–70. [Google Scholar]

- Black, L.L.; Wu, D.L.; Wang, J.F.; Kalb, T.; Bbass, D.; Chen, J.H. Grafting tomatoes for production in the hot-wet season. Asian Veg. Res. Dev. Cent. 2003, 3, 551. [Google Scholar]

- Gisbert, C.; Prohens, J.; Nuez, F. Performance of eggplant grafted onto cultivated, wild, and hybrid materials of eggplant and tomato. Int. J. Plant Prod. 2011, 5, 367–380. [Google Scholar]

- Vargas, Y.; Nicolalde, J.; Alcívar, W.; Moncayo, L.; Caicedo, C.; Pico, J.; Ron, G.L.; Viera-Arroyo, W. Response of wild Solanaceae to Meloidogyne incognita inoculation and its graft compatibility with tree tomato (Solanum betaceum). Nematropica 2018, 48, 126–135. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.Q.; Wei, J.Z.; Tan, A.; Aroian, R.V. Resistance to root-knot nematode in tomato roots expressing a nematicidal Bacillus thuringiensis crystal protein. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2007, 5, 455–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, T.K.; Papolu, P.K.; Banakar, P.; Choudhary, D.; Sirohi, A.; Rao, U. Tomato transgenic plants expressing hairpin construct of a nematode protease gene conferred enhanced resistance to root-knot nematodes. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nyaku, S.T.; Amissah, N. Grafting: An effective strategy for nematode management in tomato genotypes. In Recent Advances in Tomato Breeding and Production; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivard, C.L.; Louws, F.J. Grafting to manage soil-borne diseases in heirloom tomato production. HortScience 2008, 43, 2008–2111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, C.E.; Zhao, X.; Hodges, A.W. Cost–benefit analysis of using grafted transplants for root-knot nematode management in organic heirloom tomato production. HortTechnology 2012, 22, 252–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owusu, S.B.; Kwoseh, C.K.; Starr, J.L.; Davies, F.T. Grafting for management of root-knot nematodes, Meloidogyne incognita, in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.). Nematropica 2016, 46, 14–21. [Google Scholar]

- Baidya, S.; Timila, R.D.; Kc, R.B.; Manandhar, H.K.; Manandhar, C. Management of root-knot nematode on tomato through grafting rootstock of Solanum sisymbriifolium. J. Nepal Agric. Res. Counc. 2017, 3, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomason, I.J. Challenges facing nematology: Environmental risks with nematicides and the need for new approaches. In Vistas on Nematology; Veech, J.A., Dickson, D.W., Eds.; Society of Nematologists: Hyattsville, MD, USA, 1987; pp. 469–476. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, W.M.; Abdel-Mageed, M.A.; Hegazy, M.G.A.; Abou-Shlell, M.K.; Sultan, S.M.E.; Salama, E.A.A.; Yousef, A.F. Biocontrol agent of root-knot nematode Meloidogyne javanica and root-rot fungus Fusarium solani in okra: Morphological, anatomical characteristics and productivity under greenhouse conditions. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 11103. [Google Scholar]

- Sahebani, N.; Gholamrezaee, N. The biocontrol potential of Pseudomonas fluorescens CHA0 against root-knot nematode (Meloidogyne javanica) is dependent on the plant species. Biol. Control 2021, 152, 104445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishore, K.; Mukesh, C.; Meghvansi, K. Sustainable Management of Nematodes in Agriculture: Organic Management. Available online: https://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3-031-09943-4 (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Lawal, I.; Fardami, A.Y.; Ahmad, F.I.; Yahaya, S.; Abubakar, A.S.; Sa’id, M.A.; Marwana, M.; Maiyadi, K.A. A review on nematophagus fungi: A potential nematicide for the biocontrol of nematodes. J. Environ. Biomed. Toxicol. 2022, 5, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayaz, M.; Zhao, J.-T.; Zhao, W.; Chi, Y.-K.; Ali, Q.; Ali, F.; Khan, A.R.; Yu, Q.; Yu, J.-W.; Wu, W.-C.; et al. Biocontrol of plant parasitic nematodes by bacteria and fungi: A multi-omics approach for the exploration of novel nematicides in sustainable agriculture. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1433716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayaz, M.; Ali, Q.; Farzand, A.; Khan, A.R.; Ling, H.; Gao, X. Nematicidal volatiles from Bacillus atrophaeus GBSC56 promote growth and stimulate induced systemic resistance in tomato against Meloidogyne incognita. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 5049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migunova, V.D.; Sasanelli, N. Bacteria as biocontrol tools against phytoparasitic nematodes. Plants 2021, 10, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussey, R.S.; Barker, K.R. A comparison of methods of collecting inocula of Meloidogyne spp., including a new technique. Plant Dis. Rep. 1973, 57, 1025–1028. [Google Scholar]

- Singleton, V.L.; Orthofer, R.; Lamuela-Raventós, R.M. Analysis of total phenols and other oxidation substrates and antioxidants by means of Folin–Ciocalteu reagent. Methods Enzymol. 1999, 299, 152–178. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, M.G.; Thompson, W.F. Rapid isolation of high molecular weight plant DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1980, 8, 4321–4325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saghai-Maroof, M.A.; Soliman, K.M.; Jorgensen, R.A.; Allard, R.W. Ribosomal DNA spacer length polymorphism in barley: Mendelian inheritance, chromosomal location and population dynamics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1984, 81, 8014–8018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.W.; Magill, C.W.; Schertz, K.F.; Hart, G.E. An RFLP linkage map of Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench. Theor. Appl. Genet. 1994, 89, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cobb, N.A. Estimating the nematode population of soil. Agric. Tech. Circ. 1918, 1, 48. [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead, A.G.; Hemming, J.R. A comparison of some quantitative methods of extracting small vermiform nematodes from soil. Ann. Appl. Biol. 1965, 55, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basavaraj, V.; Sharada, M.S.; Mahesh, H.M.; Sampathkumar, M.R. Survey for root-knot nematode infestation in bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) fields in Mysore District of Karnataka. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 2023, 12, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawade, B.H.; Chaturvedi, S.; Khan, Z.; Pandey, C.D.; Gangopadhyay, K.K.; Dubey, S.C.; Chalam, V.C. Evaluation of brinjal germplasm against root-knot nematode, Meloidogyne incognita. Indian Phytopathol. 2022, 75, 449–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, N.; Sharma, J.L. Evaluation of brinjal (Solanum melongena) varieties for resistance to root-knot nematode, Meloidogyne incognita. Glob. J. Biosci. Biotechnol. 2013, 2, 560–562. [Google Scholar]

- Sumita, K.; Patidar, R.K. Screening of brinjal germplasm against Meloidogyne incognita under Arunachal Pradesh conditions. Int. J. Sci. Res. 2015, 6, 954–955. [Google Scholar]

- Kaur, S.; Dhatt, A.S. Screening of cultivated and wild brinjal germplasm for resistance against root-knot nematode, M. incognita. Indian J. Nematol. 2017, 47, 129–131. [Google Scholar]

- Dhivya, R.; Sadasakthi, A.; Sivakumar, M. Response of wild Solanum rootstocks to root-knot nematode (Meloidogyne incognita Kofoid and White). Int. J. Plant Sci. 2014, 9, 117–122. [Google Scholar]

- Nayak, D.K.; Pandey, R. Screening and evaluation of brinjal varieties/cultivars against root-knot nematode, Meloidogyne incognita. Int. J. Adv. Res. 2015, 3, 476–479. [Google Scholar]

- Das, S.; Wadud, M.A.; Chakraborty, S.; Khokon, M.A.R. Biorational management of root-knot of brinjal (Solanum melongena L.) caused by Meloidogyne javanica. Heliyon 2022, 8, e09227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Qurashi, M.A.; Al-Yahya, F.; Almasrahi, A.; Shakeel, A. Growth and resistance response of eleven eggplant cultivars to infection by the Javanese root-knot nematode Meloidogyne javanica under greenhouse conditions. Plant Prot. Sci. 2025, 61, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewi, A.; Indarti, S. Screening resistance of several accessions of eggplant (Solanum melongena L.) against root-knot nematodes (Meloidogyne incognita). In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Smart and Innovative Agriculture (ICoSIA 2021), Yogyakarta, Indonesia, 3–4 November 2021; Volume 19, pp. 180–190. [Google Scholar]

- Bakker, E.; Dees, R.; Bakker, J.; Goverse, A. Mechanisms involved in plant resistance to nematodes. In Multigenic and Induced Systemic Resistance in Plants; Tuzun, S., Bent, E., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Nayak, D.K. Effects of nematode infection on contents of phenolic substances as influenced by root-knot nematode, Meloidogyne incognita, in susceptible and resistant brinjal cultivars. Agric. Sci. Dig. Res. J. 2015, 35, 163–164. [Google Scholar]

- Shaaban, M.; Mahdy, M.; Selim, M.; Mousa, E. Pathological, chemical and molecular analysis of eggplant varieties infected with root-knot nematodes (Meloidogyne spp.). Egypt. J. Crop Prot. 2023, 18, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gujjala, N.; Swamy, K.; Kambham, D.M.R.; Ponnam, D.N.; Tejavathu, H.S.; Singh, G.; Kumar, H.S. Evaluation of F1 hybrids against root-knot nematode (Meloidogyne incognita) resistance in brinjal (Solanum melongena L.). J. Hortic. Sci. 2024, 19, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, V.; Ho, J.; Wu, F.; Miller, N.; Kaloshian, I. A PCR-based marker tightly linked to the nematode resistance gene Mi in tomato. Theor. Appl. Genet. 1994, 87, 757–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milligan, S.B.; Bodeau, J.; Yaghoobi, J.; Kaloshian, I.; Zabel, P.; Williamson, V.M. The root-knot nematode resistance gene Mi from tomato is a member of the leucine zipper, nucleotide-binding, leucine-rich repeat family of plant genes. Plant Cell 1998, 10, 1307–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammiraju, J.S.; Veremis, J.C.; Huang, X.; Roberts, P.A.; Kaloshian, I. The heat-stable root-knot nematode resistance gene Mi-9 from Lycopersicon peruvianum is localized on the short arm of chromosome 6. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2003, 106, 478–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaghoobi, J.; Yates, J.L.; Williamson, V.M. Fine mapping of the nematode resistance gene Mi-3 in Solanum peruvianum and construction of an S. lycopersicum DNA contig spanning the locus. Mol. Genet. Genom. 2005, 274, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Xie, Q.; Smith-Becker, J.; Navarre, D.A.; Kaloshian, I. Mi-1-mediated aphid resistance involves salicylic acid and mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling cascades. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2006, 19, 655–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arens, P.; Mansilla, C.; Deinum, D.; Cavellini, L.; Moretti, A.; Rolland, S.; van der Schoot, H.; Calvache, D.; Ponz, F.; Collonnier, C.; et al. Development and evaluation of robust molecular markers linked to disease resistance in tomato for distinctness, uniformity and stability testing. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2010, 120, 655–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, V.S.; Pitambara; Shukla, Y.M. Screening of various tomato genotypes for resistance to root-knot nematode (Meloidogyne incognita) infection. Int. J. Chem. Stud. 2018, 6, 1434–1438. [Google Scholar]

- Öçal, S.; Devran, Z. Response of eggplant genotypes to avirulent and virulent populations of Meloidogyne incognita (Kofoid & White, 1919) Chitwood, 1949 (Tylenchida: Meloidogynidae). Turk. Entomol. Derg. 2019, 43, 287–300. [Google Scholar]

- Ainurrachmah, A.; Indarti, S.; Taryono, T. Assessment of root-knot nematode resistance in eggplant accessions by using molecular markers. SABRAO J. Breed. Genet. 2021, 53, 468–478. [Google Scholar]

- Bahadur, A.; Rai, N.; Kumar, R.; Tiwari, S.K.; Rai, A.; Singh, U.; Patel, P.; Tiwari, V.; Rai, A.; Singh, M.; et al. Grafting tomato on eggplant as a potential tool to improve water logging tolerance in hybrid tomato. Veg. Sci. 2015, 42, 82–87. [Google Scholar]

- Djidonou, D.; Gao, Z.; Zhao, X. Economic analysis of grafted tomato production in sandy soils in northern Florida. Hort. Technol. 2013, 23, 613–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draie, R. The role of grafting technique to improve tomato growth and production under infestation by the branched broomrape. Compr. Res. J. Agric. Sci. 2017, 2, 19–29. [Google Scholar]

- Abd-Elgawad, M.M.M. Biological control of nematodes infecting eggplant in Egypt. Bull. Natl. Res. Cent. 2021, 45, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokbel, A.A.; Alharbi, A.A. Suppressive effect of some microbial agents on root-knot nematode, Meloidogyne javanica, infecting eggplant. Aust. J. Crop Sci. 2014, 8, 1428–1434. [Google Scholar]

| S. No. | Accessions/Varieties | Average Root Galls/Roots | Average Egg Masses/Roots | Average RKN Index | Categorization |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Hisar Shymal | 103.33 ± 1.66 | 100.33 ± 1.45 | 4.66 ± 0.33 | HS |

| 2 | Punjab Sadabahar | 95.33 ± 2.18 | 91.00 ± 3.51 | 4.66 ± 0.33 | HS |

| 3 | Punjab Barsati | 103.33 ± 2.18 | 99.33 ± 2.33 | 4.66 ± 0.33 | HS |

| 4 | Punjab Rounak | 102.33 ± 1.20 | 98.33 ± 3.28 | 4.66 ± 0.33 | HS |

| 5 | Punjab Bharpoor | 126.33 ± 3.18 | 123.66 ± 2.96 | 5.00 ± 0.00 | HS |

| 6 | Pusa Uttam | 85.66 ± 1.76 | 82.33 ± 1.33 | 4.00 ± 0.00 | S |

| 7 | PusaShymala | 88.66 ± 5.20 | 84.66 ± 3.18 | 4.33 ± 0.33 | HS |

| 8 | Pusa Ankur | 102.66 ± 3.93 | 97.66 ± 3.93 | 4.66 ± 0.33 | HS |

| 9 | PusaBindu | 92.33 ± 2.60 | 89.66 ± 2.60 | 4.00 ± 0.00 | S |

| 10 | Pusa Purple Round | 129.66 ± 0.88 | 126.00 ± 1.00 | 5.00 ± 0.00 | HS |

| 11 | PusaOishiki | 100.33 ± 1.85 | 95.33 ± 2.40 | 4.33 ± 0.33 | HS |

| 12 | Pusa Anupam | 125.66 ± 2.33 | 121.66 ± 1.20 | 4.66 ± 0.33 | HS |

| 13 | Pusa Hara Bengan | 141.33 ± 2.90 | 136.33 ± 2.33 | 5.00 ± 0.00 | HS |

| 14 | Green Long | 89.66 ± 1.66 | 85.33 ± 2.33 | 4.33 ± 0.33 | HS |

| 15 | Harsh | 137.66 ± 3.71 | 133.33 ± 3.33 | 5.00 ± 0.00 | HS |

| 16 | Udit | 168.33 ± 4.91 | 164.00 ± 3.05 | 5.00 ± 0.00 | HS |

| 17 | Pink Long | 130.33 ± 2.60 | 125.66 ± 4.84 | 5.00 ± 0.00 | HS |

| 18 | Mahadeva | 141.33 ± 1.85 | 137.33 ± 2.60 | 5.00 ± 0.00 | HS |

| 19 | Nisha | 148.66 ± 2.40 | 144.00 ± 2.00 | 5.00 ± 0.00 | HS |

| 20 | Choo-choo | 163.33 ± 3.33 | 159.33 ± 1.20 | 5.00 ± 0.00 | HS |

| 21 | Kokila | 153.66 ± 3.18 | 147.66 ± 4.33 | 5.00 ± 0.00 | HS |

| 22 | KSP1324 | 176.66 ± 4.40 | 171.66 ± 7.26 | 5.00 ± 0.00 | HS |

| 23 | Janak | 137.33 ± 1.45 | 133.33 ± 2.84 | 5.00 ± 0.00 | HS |

| 24 | Navkiran | 140.33 ± 3.93 | 135.00 ± 2.64 | 5.00 ± 0.00 | HS |

| 25 | Bharta 436 | 174.33 ± 3.48 | 171.00 ± 5.85 | 5.00 ± 0.00 | HS |

| 26 | PBH-3 | 80.33 ± 2.90 | 75.33 ± 3.18 | 4.33 ± 0.33 | HS |

| 27 | NBH-459 | 168.33 ± 4.05 | 162.66 ± 3.84 | 5.00 ± 0.00 | HS |

| 28 | Reema | 191.66 ± 5.54 | 187.66 ± 6.06 | 5.00 ± 0.00 | HS |

| 29 | Mahy-112 | 196.66 ± 4.40 | 192.66 ± 3.66 | 5.00 ± 0.00 | HS |

| 30 | Mahy-80 | 156.33 ± 2.90 | 152.66 ± 3.71 | 5.00 ± 0.00 | HS |

| 31 | BR1 | 104.33 ± 2.18 | 100.33 ± 2.33 | 4.66 ± 0.33 | HS |

| 32 | BR2 | 105.33 ± 2.18 | 101.33 ± 3.48 | 4.66 ± 0.33 | HS |

| 33 | BR3 | 6.66 ± 0.66 | 4.66 ± 0.33 | 2.00 ± 0.00 | R |

| 34 | BR4 | 102.33 ± 2.33 | 98.66 ± 3.28 | 4.33 ± 0.33 | HS |

| 35 | BR5 | 145.33 ± 3.71 | 139.66 ± 5.23 | 5.00 ± 0.00 | HS |

| Critical Difference (C.D.) | 8.73 | 9.72 | 0.57 | ||

| Critical Variance (C.V.) | 4.24 | 4.88 | 7.49 | ||

| S. No. | Varieties/Accessions of Eggplant | TPC µg/g of Root in Uninfected Eggplant | TPC µg/g of Root in RKN-Infected Eggplant |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Hisar Shymal | 455.55 ± 2.22 | 621.47 ± 3.29 |

| 2 | Punjab Sadabahar | 537.77 ± 3.88 | 618.88 ± 8.91 |

| 3 | Punjab Barsati | 541.10 ± 1.78 | 578.51 ± 4.64 |

| 4 | Punjab Rounak | 524.44 ± 4.00 | 605.18 ± 5.60 |

| 5 | Punjab Bharpoor | 535.55 ± 4.89 | 575.55 ± 3.56 |

| 6 | Pusa Uttam | 558.33 ± 2.22 | 760.36 ± 4.27 |

| 7 | PusaShymala | 583.33 ± 2.22 | 735.92 ± 6.55 |

| 8 | Pusa Ankur | 464.99 ± 1.66 | 592.59 ± 2.67 |

| 9 | Pusa Bindu | 528.88± 6.66 | 787.77 ± 6.79 |

| 10 | Pusa Purple Round | 414.99 ± 2.77 | 671.84 ± 1.04 |

| 11 | PusaOishiki | 527.77 ± 3.33 | 688.88 ± 5.25 |

| 12 | Pusa Anupam | 492.77 ± 3.66 | 556.66 ± 2.31 |

| 13 | Pusa Hara Bengan | 397.77 ± 2.22 | 576.29 ± 2.25 |

| 14 | Green Long | 563.88 ± 3.66 | 806.66 ± 2.00 |

| 15 | Harsh | 337.22 ± 5.00 | 541.47 ± 2.09 |

| 16 | Udit | 302.77 ± 3.88 | 449.62 ± 2.26 |

| 17 | Pink Long | 431.10 ± 2.22 | 570.36 ± 1.83 |

| 18 | Mahadeva | 391.11 ± 1.11 | 559.99 ± 3.90 |

| 19 | Nisha | 392.77 ± 5.55 | 544.81 ± 3.76 |

| 20 | Choo-choo | 302.21 ± 3.33 | 472.96 ± 1.61 |

| 21 | Kokila | 357.77 ± 5.55 | 473.32 ± 2.31 |

| 22 | KSP1324 | 280.55 ± 1.67 | 376.66 ± 3.33 |

| 23 | Janak | 399.44 ± 3.88 | 566.29 ± 5.74 |

| 24 | Navkiran | 522.22 ± 2.22 | 574.81 ± 3.29 |

| 25 | Bharta 436 | 337.22 ± 5.00 | 408.88 ± 5.83 |

| 26 | PBH-3 | 614.44 ± 3.33 | 806.66 ± 3.25 |

| 27 | NBH-459 | 333.88 ± 5.00 | 405.55 ± 3.39 |

| 28 | Reema | 286.11 ± 6.11 | 343.70 ± 3.15 |

| 29 | Mahy-112 | 244.44 ± 5.56 | 309.25 ± 5.73 |

| 30 | Mahy-80 | 343.88 ± 8.33 | 491.10 ± 3.20 |

| 31 | BR1 | 537.21 ± 0.58 | 704.81 ± 2.42 |

| 32 | BR2 | 614.44 ± 6.67 | 714.81 ± 1.78 |

| 33 | BR3 | 694.44 ± 5.56 | 1515.92 ± 5.74 |

| 34 | BR4 | 577.77 ± 7.77 | 785.55 ± 4.13 |

| 35 | BR5 | 421.66 ± 1.66 | 559.62 ± 4.17 |

| CD | 12.43 | 11.87 | |

| CV | 1.34 | 1.19 | |

| S. No. | Type of Grafting | Success Percentage | Number of Days Taken for Grafting |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Cleft Grafting | 23.33 ± 3.33 | 29.44 ± 1.47 |

| 2 | Shaft Grafting | 90.00 ± 5.77 | 21.27 ± 0.19 |

| 3 | Tip Grafting | 13.33 ± 3.33 | 33.50 ± 0.86 |

| Critical Difference (C.D.) | 15.18 | 3.50 | |

| Critical Variance (C.V.) | 17.65 | 6.12 |

| S. No. | Parameter Observed | * Negative Control (T1) | ** Positive Control (T2) | Biocontrol Agents @2 g/kg of Soil | Biocontrol Agents @4 g/kg of Soil | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T. viride (T3) | P. lilacinus (T3) | P. fluorescence (T4) | T. viride (T5) | P. lilacinus (T6) | P. fluorescence (T7) | ||||

| 1 | Number of Root Galls/Root | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 8.66 ± 0.33 | 7.66 ± 0.33 | 4.33 ± 0.33 | 4.66 ± 0.33 | 6.66 ± 0.66 | 1.33 ± 0.33 | 2.33 ± 0.33 |

| 2 | Number of Egg Masses/Root | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 7.66 ± 0.33 | 5.66 ± 0.66 | 2.66 ± 0.33 | 3.00 ± 0.57 | 3.33 ± 0.33 | 0.33 ± 0.33 | 1.33 ± 0.33 |

| 3 | Final Nematode Population/200 mL of Soil | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 227.33 ± 1.45 | 175.00 ± 2.88 | 86.33 ± 1.20 | 94.33 ± 1.76 | 105.33 ± 0.88 | 40.66 ± 2.18 | 71.00 ± 1.15 |

| 4 | Plant Height (cm) | 38.80 ± 0.26 | 34.33 ± 0.41 | 35.56 ± 0.41 | 36.36 ± 0.43 | 35.40 ± 0.32 | 36.10 ± 0.51 | 38.36 ± 0.51 | 35.43 ± 0.29 |

| 5 | Fresh Weight of Shoots (g) | 27.18 ± 0.43 | 24.52 ± 0.63 | 25.78 ± 0.23 | 26.30 ± 0.36 | 24.66 ± 0.12 | 25.40 ± 0.20 | 26.89 ± 0.31 | 26.02 ± 0.40 |

| 6 | Dry Weight of Shoots (g) | 5.26 ± 0.11 | 4.07 ± 0.06 | 4.86 ± 0.05 | 5.01 ± 0.10 | 4.69 ± 0.12 | 4.83 ± 0.08 | 5.29 ± 0.22 | 5.16 ± 0.10 |

| 7 | Fresh Weight of Roots (g) | 6.45 ± 0.05 | 7.79 ± 0.03 | 5.02 ± 0.06 | 5.50 ± 0.04 | 4.84 ± 0.05 | 4.71 ± 0.14 | 5.80 ± 0.04 | 5.25 ± 0.15 |

| 8 | Dry Weight of Roots (g) | 1.95 ± 0.02 | 1.26 ± 0.04 | 1.58 ± 0.08 | 1.87 ± 0.05 | 1.67 ± 0.03 | 1.82 ± 0.06 | 1.91 ± 0.08 | 1.75 ± 0.05 |

| 9 | Total Phenolic Content µg/gm in Roots | 670.73 ± 3.53 | 1493.21 ± 3.41 | 1519.16 ± 3.19 | 1588.96 ± 4.42 | 1580.53 ± 1.12 | 1572.26 ± 6.05 | 1691.80 ± 4.86 | 1604.43 ± 4.61 |

| Critical Difference (C.D.) | 3.36 | 3.63 | 4.17 | 4.38 | 2.08 | 5.81 | 5.09 | 4.51 | |

| Critical Variance (C.V.) | 2.48 | 1.15 | 1.34 | 1.42 | 0.67 | 1.88 | 1.60 | 1.47 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Poonia, A.K.; Koul, B.; Kajla, S.; Mishra, M.; Rabbee, M.F. Grafting Tomato Scions on Root Knot Nematode (RKN)-Resistant Brinjal Rootstocks Complemented with Biocontrol Agents as an Integrated Nematode Management (INM) Strategy for the Development of RKN-Resistant Tomato. Pathogens 2025, 14, 1257. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121257

Poonia AK, Koul B, Kajla S, Mishra M, Rabbee MF. Grafting Tomato Scions on Root Knot Nematode (RKN)-Resistant Brinjal Rootstocks Complemented with Biocontrol Agents as an Integrated Nematode Management (INM) Strategy for the Development of RKN-Resistant Tomato. Pathogens. 2025; 14(12):1257. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121257

Chicago/Turabian StylePoonia, Anil K., Bhupendra Koul, Subhash Kajla, Meerambika Mishra, and Muhammad Fazle Rabbee. 2025. "Grafting Tomato Scions on Root Knot Nematode (RKN)-Resistant Brinjal Rootstocks Complemented with Biocontrol Agents as an Integrated Nematode Management (INM) Strategy for the Development of RKN-Resistant Tomato" Pathogens 14, no. 12: 1257. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121257

APA StylePoonia, A. K., Koul, B., Kajla, S., Mishra, M., & Rabbee, M. F. (2025). Grafting Tomato Scions on Root Knot Nematode (RKN)-Resistant Brinjal Rootstocks Complemented with Biocontrol Agents as an Integrated Nematode Management (INM) Strategy for the Development of RKN-Resistant Tomato. Pathogens, 14(12), 1257. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121257