Evidence of Toxoplasma gondii in Neural and Cardiac Tissues of Wild Rodents in Lithuania

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

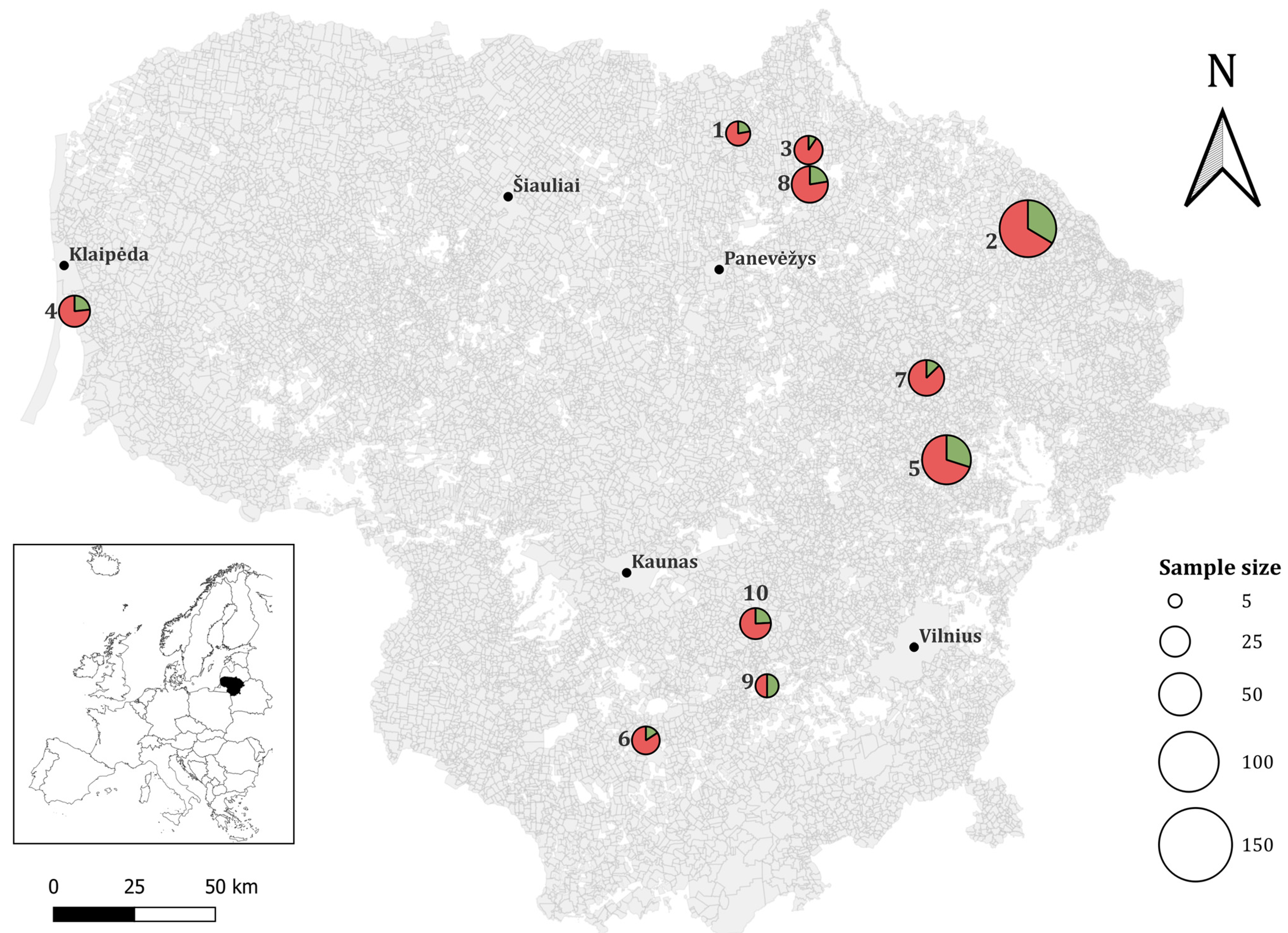

2.1. Sample Collection

2.2. gDNA Extraction and Molecular Analysis

2.3. Sequencing Analysis

2.4. Bioinformatical and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Prevalence of T. gondii in Wild Rodent Species in Lithuania

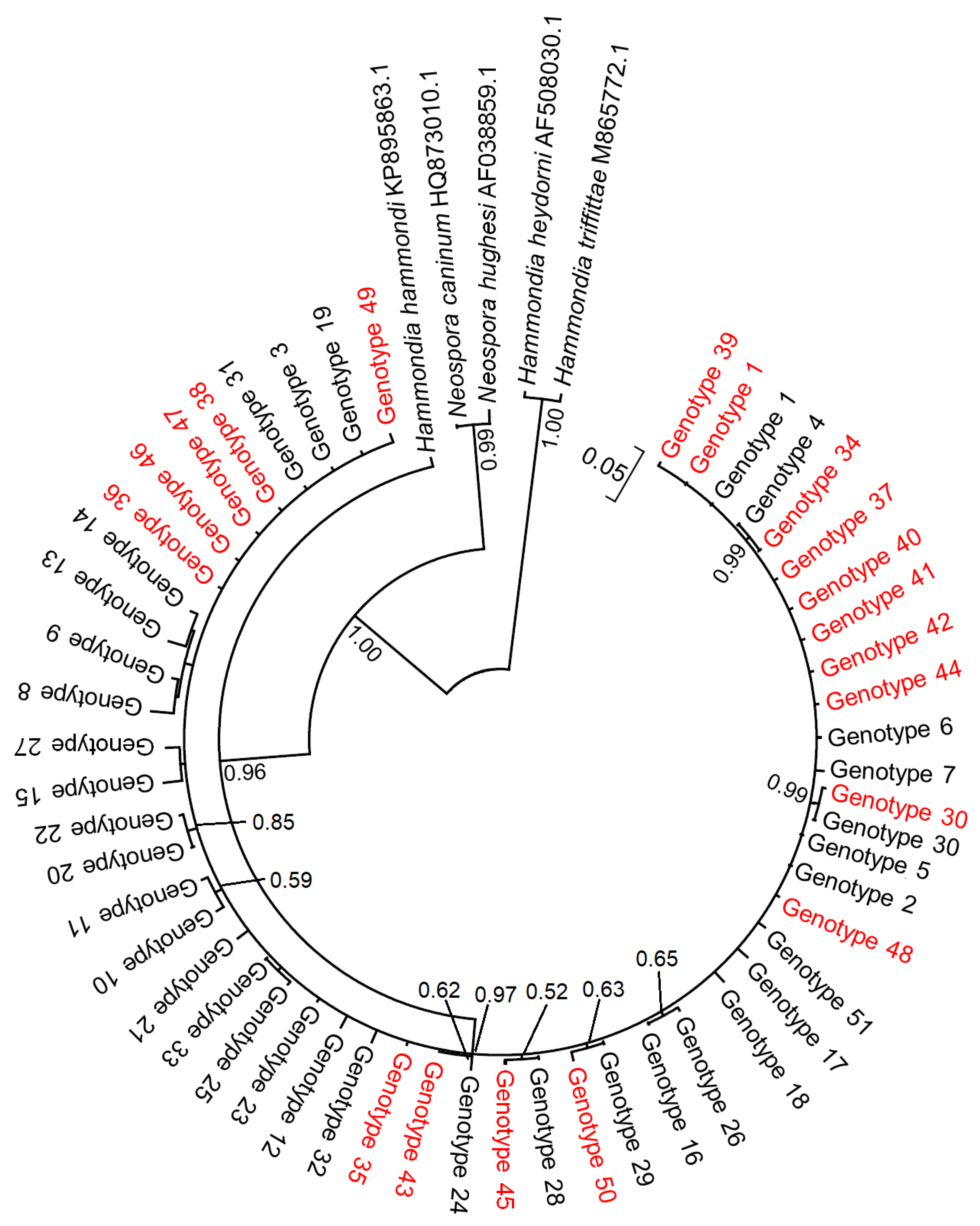

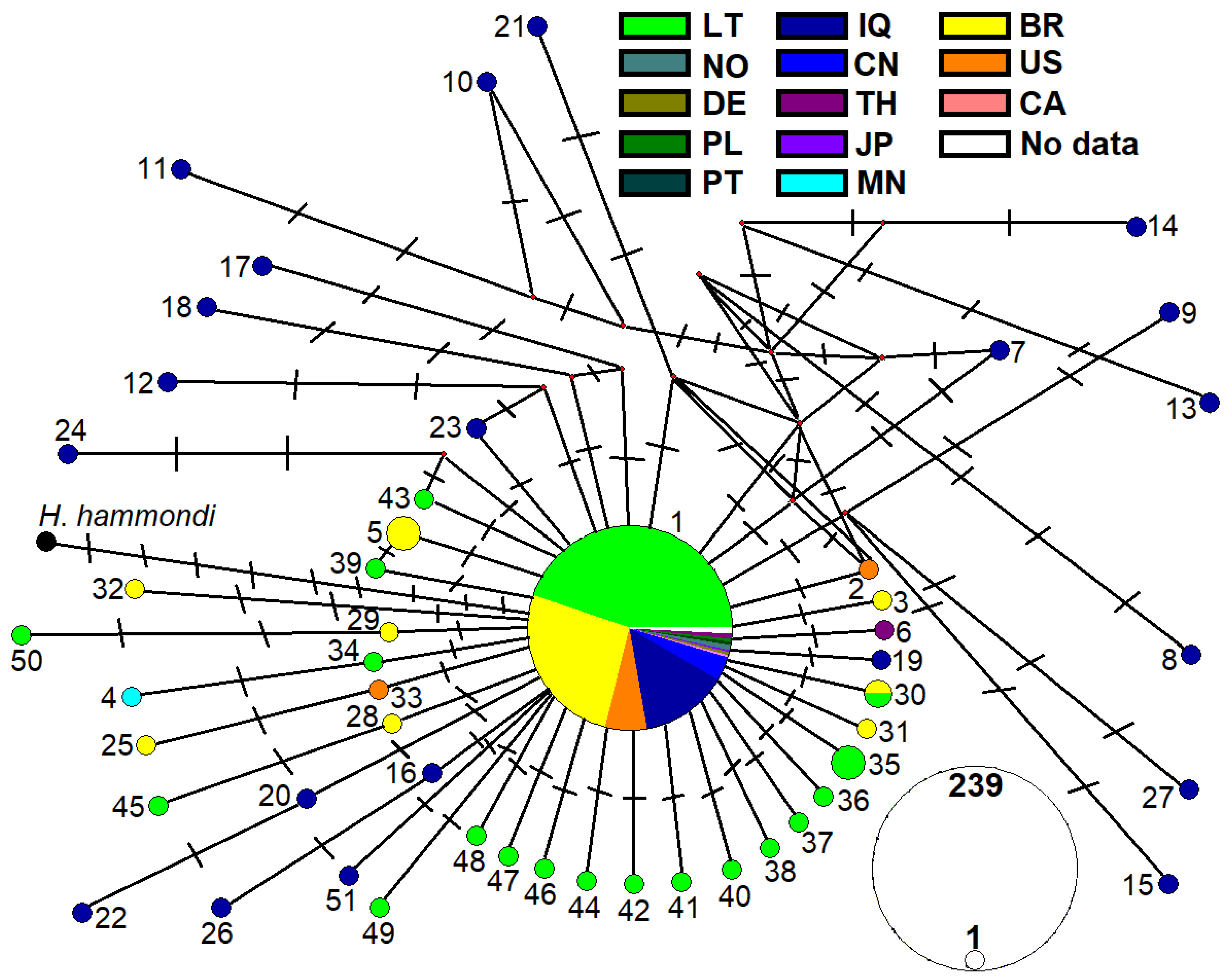

3.2. Distribution of ITS1 Genotypes

3.3. Genetic Variability of T. gondii from Rodents in Lithuania

4. Discussion

4.1. Trends in the Prevalence of Toxoplasma gondii in Wild Rodents in Europe

4.2. Ecological and Tissue-Specific Dynamics of Toxoplasma gondii in Wild Rodents

4.3. Genetic Diversity and Ecological Implications of Toxoplasma gondii in Lithuanian Rodents

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dubey, J.P. Toxoplasmosis of Animals and Humans, 3rd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2022; p. 542. [Google Scholar]

- Tenter, A.M.; Heckeroth, A.R.; Weiss, L.M. Toxoplasma gondii: From animals to humans. Int. J. Parasitol. 2000, 30, 1217–1258, Erratum in Int. J. Parasitol. 2001, 31, 217–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montazeri, M.; Mikaeili Galeh, T.; Moosazadeh, M.; Sarvi, S.; Dodangeh, S.; Javidnia, J.; Sharif, M.; Daryani, A. The global serological prevalence of Toxoplasma gondii in felids during the last five decades (1967–2017): A systematic review and meta-analysis. Parasites Vectors 2020, 13, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hide, G.; Morley, E.K.; Hughes, J.M.; Gerwash, O.; Elmahaishi, M.S.; Elmahaishi, K.H.; Thomasson, D.; Wright, E.A.; Williams, R.H.; Murphy, R.G.; et al. Evidence for high levels of vertical transmission in Toxoplasma gondii. Parasitology 2009, 136, 1877–1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shapiro, K.; Bahia-Oliveira, L.; Dixon, B.; Dumètre, A.; de Wit, L.A.; VanWormer, E.; Villena, I. Environmental transmission of Toxoplasma gondii: Oocysts in water, soil, and food. Food Waterborne Parasitol. 2019, 15, e00049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almería, S.; Dubey, J.P. Foodborne transmission of Toxoplasma gondii infection in the last decade: An overview. Res. Vet. Sci. 2021, 135, 371–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latifi, A.; Flegr, J.; Kankova, S. Re-assessing host manipulation in Toxoplasma: The underexplored role of sexual transmission—Evidence, mechanisms, implications. Folia Parasitol. 2025, 72, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eza, D.E.; Lucas, S.B. Fulminant toxoplasmosis causing fatal pneumonitis and myocarditis. HIV Med. 2006, 7, 415–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajzenberg, D.; Yera, H.; Marty, P.; Paris, L.; Dalle, F.; Menotti, J.; Aubert, D.; Franck, J.; Bessières, M.H.; Quinio, D.; et al. Genotype of 88 Toxoplasma gondii isolates associated with toxoplasmosis in immunocompromised patients and correlation with clinical findings. J. Infect. Dis. 2009, 199, 1155–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saadatnia, G.; Golkar, M. A review on human toxoplasmosis. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 2012, 44, 805–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández-Cortazar, I.; Acosta-Viana, K.Y.; Ortega-Pacheco, A.; Guzman-Marin, E.S.; Aguilar-Caballero, A.J.; Jiménez-Coello, M. Toxoplasmosis in Mexico: Epidemiological situation in humans and animals. Rev. Inst. Med. Trop. Sao Paulo 2015, 57, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabritz, H.A.; Miller, M.A.; Gardner, I.A.; Packham, A.E.; Atwill, E.R.; Conrad, P.A. Risk factors for Toxoplasma gondii infection in wild rodents from central coastal California and a review of T. gondii prevalence in rodents. J. Parasitol. 2008, 94, 675–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, J.P.; Murata, F.H.A.; Cerqueira-Cézar, C.K.; Kwok, O.C.H.; Su, C. Epidemiological significance of Toxoplasma gondii infections in wild rodents: 2009–2020. J. Parasitol. 2021, 107, 182–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Soto, M.F.; Gaona, O.; Vigueras-Galván, A.L.; Suzán, G.; Falcón, L.I.; Vázquez-Domínguez, E. Prevalence and transmission of the most relevant zoonotic and vector-borne pathogens in the Yucatan Peninsula: A review. PLoS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2024, 18, e0012286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotteland, C.; Chaval, Y.; Villena, I.; Galan, M.; Geers, R.; Aubert, D.; Poulle, M.L.; Charbonnel, N.; Gilot-Fromont, E. Species or local environment, what determines the infection of rodents by Toxoplasma gondii? Parasitology 2014, 141, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabiee, M.H.; Mahmoudi, A.; Siahsarvie, R.; Kryštufek, B.; Mostafavi, E. Rodent-borne diseases and their public health importance in Iran. PLoS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2018, 12, e0006256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galeh, T.M.; Sarvi, S.; Hosseini, S.A.; Daryani, A. Genetic diversity of Toxoplasma gondii isolates from rodents in the world: A systematic review. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2022, 69, 943–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prūsaitė, J. Fauna of Lithuania. Mammals; Mokslas: Vilnius, Lithuania, 1988; pp. 28–43. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Suleski, M.; Sanderford, M.; Sharma, S.; Tamura, K. MEGA12: Molecular evolutionary genetic analysis version 12 for adaptive and green computing. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2024, 41, msae263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milne, I.; Wright, F.; Rowe, G.; Marshall, D.F.; Husmeier, D.; McGuire, G. TOPALi: Software for automatic identification of recombinant sequences within DNA multiple alignments. Bioinformatics 2004, 20, 1806–1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandelt, H.J.; Forster, P.; Röhl, A. Median-joining networks for inferring intraspecific phylogenies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1999, 16, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajima, F. Statistical method for testing the neutral mutation hypothesis by DNA polymorphism. Genetics 1989, 123, 585–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozas, J.; Ferrer-Mata, A.; Sánchez-DelBarrio, J.C.; Guirao-Rico, S.; Librado, P.; Ramos-Onsins, S.E.; Sánchez-Gracia, A. DnaSP 6: DNA sequence polymorphism analysis of large data sets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2017, 34, 3299–3302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Excoffier, L.; Laval, G.; Schneider, S. Arlequin Ver. 3.0: An integrated software package for population genetics data analysis. Evol. Bioinform. Online 2005, 1, 47–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuehrer, H.P.; Blöschl, I.; Siehs, C.; Hassl, A. Detection of Toxoplasma gondii, Neospora caninum, and Encephalitozoon cuniculi in the brains of common voles (Microtus arvalis) and water voles (Arvicola terrestris) by gene amplification techniques in western Austria (Vorarlberg). Parasitol. Res. 2010, 107, 469–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turčeková, Ľ.; Hurníková, Z.; Spišák, F.; Miterpáková, M.; Chovancová, B. Toxoplasma gondii in protected wildlife in the Tatra National Park (TANAP), Slovakia. Ann. Agric. Environ. Med. 2014, 21, 235–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bártová, E.; Lukášová, R.; Vodička, R.; Váhala, J.; Pavlačík, L.; Budíková, M.; Sedlák, K. Epizootological study on Toxoplasma gondii in zoo animals in the Czech Republic. Acta Trop. 2018, 187, 222–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivovic, V.; Potusek, S.; Buzan, E. Prevalence and genotype identification of Toxoplasma gondii in suburban rodents collected at waste disposal sites. Parasite 2019, 26, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waindok, P.; Özbakış-Beceriklisoy, G.; Janecek-Erfurth, E.; Springer, A.; Pfeffer, M.; Leschnik, M.; Strube, C. Parasites in brains of wild rodents (Arvicolinae and Murinae) in the city of Leipzig, Germany. Int. J. Parasitol. Parasites Wildl. 2019, 10, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamaev, N.D.; Shuralev, E.A.; Nikitin, O.V.; Mukminov, M.N.; Davidyuk, Y.N.; Belyaev, A.N.; Isaeva, G.S.; Ziatdinov, V.B.; Khammadov, N.I.; Safina, R.F.; et al. Prevalence of Toxoplasma gondii infection among small mammals in Tatarstan, Russian Federation. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 22184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardo Gil, M.; Hegglin, D.; Briner, T.; Ruetten, M.; Müller, N.; Moré, G.; Frey, C.F.; Deplazes, P.; Basso, W. High prevalence rates of Toxoplasma gondii in cat-hunted small mammals—Evidence for parasite-induced behavioural manipulation in the natural environment? Int. J. Parasitol. Parasites Wildl. 2023, 20, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalmár, Z.; Sándor, A.D.; Balea, A.; Borşan, S.D.; Matei, I.A.; Ionică, A.M.; Gherman, C.M.; Mihalca, A.D.; Cozma-Petruț, A.; Mircean, V.; et al. Toxoplasma gondii in small mammals in Romania: The influence of host, season and sampling location. BMC Vet. Res. 2023, 19, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kijlstra, A.; Meerburg, B.; Cornelissen, J.; De Craeye, S.; Vereijken, P.; Jongert, E. The role of rodents and shrews in the transmission of Toxoplasma gondii to pigs. Vet. Parasitol. 2008, 156, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machačová, T.; Ajzenberg, D.; Žákovská, A.; Sedlák, K.; Bártová, E. Toxoplasma gondii and Neospora caninum in wild small mammals: Seroprevalence, DNA detection and genotyping. Vet. Parasitol. 2016, 223, 88–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krücken, J.; Blümke, J.; Maaz, D.; Demeler, J.; Ramünke, S.; Antolová, D.; Schaper, R.; von Samson-Himmelstjerna, G. Small rodents as paratenic or intermediate hosts of carnivore parasites in Berlin, Germany. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0172829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, S.; Essbauer, S.S.; Mayer-Scholl, A.; Poppert, S.; Schmidt-Chanasit, J.; Klempa, B.; Henning, K.; Schares, G.; Groschup, M.H.; Spitzenberger, F.; et al. Multiple infections of rodents with zoonotic pathogens in Austria. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2014, 14, 467–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tadin, A.; Tokarz, R.; Markotić, A.; Margaletić, J.; Turk, N.; Habuš, J.; Svoboda, P.; Vucelja, M.; Desai, A.; Jain, K.; et al. Molecular survey of zoonotic agents in rodents and other small mammals in Croatia. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2016, 94, 466–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meerburg, B.G.; De Craeye, S.; Dierick, K.; Kijlstra, A. Neospora caninum and Toxoplasma gondii in brain tissue of feral rodents and insectivores caught on farms in the Netherlands. Vet. Parasitol. 2012, 184, 317–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacob, J.; Manson, P.; Barfknecht, R.; Fredricks, T. Common vole (Microtus arvalis) ecology and management: Implications for risk assessment of plant protection products. Pest Manag. Sci. 2014, 70, 869–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Briner, T.; Favre, N.; Nentwig, W.; Airoldi, J.-P. Population dynamics of Microtus arvalis in a weed strip. Mamm. Biol. 2007, 72, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antolová, D.; Stanko, M.; Jarošová, J.; Miklisová, D. Rodents as sentinels for Toxoplasma gondii in rural ecosystems in Slovakia—Seroprevalence study. Pathogens 2023, 12, 826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grzybek, M.; Antolová, D.; Tołkacz, K.; Alsarraf, M.; Behnke-Borowczyk, J.; Nowicka, J.; Paleolog, J.; Biernat, B.; Behnke, J.M.; Bajer, A. Seroprevalence of Toxoplasma gondii among sylvatic rodents in Poland. Animals 2021, 11, 1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cañón-Franco, W.A.; López-Orozco, N.; Quiroz-Bucheli, A.; Kwok, O.C.H.; Dubey, J.P.; Sepúlveda-Arias, J.C. First serological and molecular detection of Toxoplasma gondii in guinea pigs (Cavia porcellus) used for human consumption in Nariño, Colombia, South America. Vet. Parasitol. Reg. Stud. Reports 2022, 36, 100801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghayan, S.A.; Asikyan, M.V.; Shcherbakov, O.; Ghazaryan, A.; Hayrapetyan, T.; Malkhasyan, A.; Gevorgyan, H.; Makarikov, A.; Kornienko, S.; Daryani, A. Toxoplasma gondii in rodents and shrews in Armenia, Transcaucasia. Int. J. Parasitol. Parasites Wildl. 2024, 25, 100987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowicka, J.; Antolová, D.; Lass, A.; Biernat, B.; Baranowicz, K.; Goll, A.; Krupińska, M.; Ferra, B.; Strachecka, A.; Behnke, J.M.; et al. Identification of Toxoplasma gondii in wild rodents in Poland by molecular and serological techniques. Ann. Agric. Environ. Med. 2024, 31, 626–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balčiauskas, L.; Balčiauskienė, L.; Litvaitis, J.A.; Tijušas, E. Citizen Scientists Showed a Four-Fold Increase of Lynx Numbers in Lithuania. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrero, A.; Heikkinen, J.; Holmala, K. Movement patterns and habitat selection during dispersal in Eurasian lynx. Mamm. Res. 2020, 65, 523–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Hu, S.; Wang, W.; Wu, X.; Marshall, F.B.; Chen, X.; Hou, L.; Wang, C. Earliest evidence for commensal processes of cat domestication. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 116–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahlaba, T.A.; Monadjem, A.; McCleery, R.; Belmain, S.R. Domestic cats and dogs create a landscape of fear for pest rodents around rural homesteads. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0171593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carruthers, V.B.; Suzuki, Y. Effects of Toxoplasma gondii infection on the brain. Schizophr. Bull. 2007, 33, 745–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashour, D.S.; Saad, A.E.; El Bakary, R.H.; El Barody, M.A. Can the route of Toxoplasma gondii infection affect the ophthalmic outcomes? Pathog. Dis. 2018, 76, fty056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Etougbétché, J.R.; Hamidović, A.; Dossou, H.J.; Coan-Grosso, M.; Roques, R.; Plault, N.; Houéménou, G.; Badou, S.; Missihoun, A.A.; Abdou Karim, I.Y.; et al. Molecular prevalence, genetic characterization and patterns of Toxoplasma gondii infection in domestic small mammals from Cotonou, Benin. Parasite 2022, 29, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouaicha, F.; Amairia, S.; Amdouni, Y.; Elati, K.; Bensmida, B.; Rekik, M.; Gharbi, M. Molecular and serological detection of Toxoplasma gondii in two species of rodents: Ctenodactylus gundi (Rodentia, Ctenodactylidae) and Psammomys obesus (Rodentia, Muridae) from South Tunisia. Vet. Med. Sci. 2025, 11, e70371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dao, A.; Fortier, B.; Soete, M.; Plenat, F.; Dubremetz, J.F. Successful reinfection of chronically infected mice by a different Toxoplasma gondii genotype. Int. J. Parasitol. 2001, 31, 63–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, K.D.; Camejo, A.; Melo, M.B.; Cordeiro, C.; Julien, L.; Grotenbreg, G.M.; Frickel, E.M.; Ploegh, H.L.; Young, L.; Saeij, J.P. Toxoplasma gondii superinfection and virulence during secondary infection correlate with the exact ROP5/ROP18 allelic combination. mBio 2015, 6, e02280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, T.; Graham, D.H.; Dahl, E.; Sreekumar, C.; Launer, F.; Corn, J.L.; Gamble, H.R.; Dubey, J.P. Transmission dynamics of Toxoplasma gondii on a pig farm. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2003, 3, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Camp, L.; Patel, A.; VanWormer, E.; Shapiro, K. High prevalence and diversity of Toxoplasma gondii DNA in feral cat feces from coastal California. PLoS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2023, 17, e0011829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Jiang, W. Virulence evolution of Toxoplasma gondii within a multi-host system. Evol. Appl. 2023, 16, 721–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sibley, L.D.; Ajioka, J.W. Population structure of Toxoplasma gondii: Clonal expansion driven by infrequent recombination and selective sweeps. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2008, 62, 329–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azimpour-Ardakan, T.; Fotouhi-Ardakani, R.; Hoghooghi-Rad, N.; Rokni, N.; Motallebi, A. Phylogenetic analysis and genetic polymorphisms evaluation of ROP8 and B1 genes of Toxoplasma gondii in livestock and poultry hosts of Yazd, Qom and Golestan provinces of Iran. Iran J. Parasitol. 2021, 16, 576–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, J.P. The effect of Toxoplasma gondii on animal behavior: Playing cat and mouse. Schizophr. Bull. 2007, 33, 752–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- House, P.K.; Vyas, A.; Sapolsky, R. Predator cat odors activate sexual arousal pathways in brains of Toxoplasma gondii-infected rats. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e23277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, Q.B.; Zeng, A.; Xie, L.H.; Qiu, H.Y.; Wang, C.R.; Zhang, X.X. Prevalence and risk factors of Toxoplasma gondii infection among five wild rodent species from five provinces of China. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2021, 21, 105–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brouat, C.; Diagne, C.A.; Ismaïl, K.; Aroussi, A.; Dalecky, A.; Bâ, K.; Kane, M.; Niang, Y.; Diallo, M.; Sow, A.; et al. Seroprevalence of Toxoplasma gondii in commensal rodents sampled across Senegal, West Africa. Parasite 2018, 25, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dellarupe, A.; Fitte, B.; Pardini, L.; Campero, L.M.; Bernstein, M.; Robles, M.D.R.; Moré, G.; Venturini, M.C.; Unzaga, J.M. Toxoplasma gondii and Neospora caninum infections in synanthropic rodents from Argentina. Rev. Bras. Parasitol. Vet. 2019, 28, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Primer Name | Sequence 5′-3′ | Region | Fragment Size | nPCR Round |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TgNN3 | GAATCCCAAGCAAAACATGAG | ITS1 | 384 bp | I |

| TgNN5R | CCAAGACATCCATTGCTGAAA | 5.8S rRNA | ||

| TgNP3 | AAGCGTGATAGTATCGAAAGG | ITS1 | 281 bp | II |

| TgNP5R | GAAGCAATCTGAAAGCACATC | ITS1 |

| Species | Overall | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. agrarius | A. flavicollis | C. glareolus | M. arvalis | M. agrestis | M. minutus | M. musculus | A. oeconomus | n/N (%, CI) | ||

| Tissue | Heart | 9.1 (2.5–21.7) | 8.7 (4.4–15.0) | 23.3 (16.3–31.5) | 19.2 (11.0–30.1) | 50.0 (15.7–84.3) | 33.3 (11.8–61.6) | 0 | 0 | 68/401 (17.0, 13.4–21.0) |

| Brain | 17.2 (5.9–35.8) | 19.5 (13.7–26.5) | 11.2 (6.4–17.8) | 13.8 (6.2–25.4) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 59/401 (14.7, 11.4–18.6) | |

| Age | Juvenile | 27.3 (6.0–61.0) | 28.0 (12.1–49.4) | 27.3 (16.1–41.0) | 20.1 (7.2–42.2) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 30/115 (26.1, 18.3–35.1) |

| Sub-adult | 12.5 (1.6–38.4) | 30.6 (18.3–45.4) | 23.9 (12.6–38.8) | 37.5 (18.8–59.4) | 60.0 (14.7–94.7) | N/A | N/A | N/A | 39/138 (28.3, 20.9–36.6) | |

| Adult | 20.0 (4.3–48.1) | 20.7 (12.9–30.4) | 34.0 (21.5–48.3) | 25.0 (9.8–46.7) | 33.3 (0.8–90.6) | 66.7 (9.4–99.2) | 0 | 0 | 50/197 (25.4, 19.5–32.1) | |

| Undet. | 0 | 100 (2.5–100) | 0 | 0 | N/A | 25.0 (5.5–57.2) | N/A | N/A | 4/19 (21.1, 6.1–45.6) | |

| Sex | Female | 13.6 (2.1–34.9) | 18.1 (10.0–28.9) | 32.2 (20.6–45.6) | 16.3 (6.8–30.7) | 60.0 (14.7–94.7) | 50.0 (1.3–98.7) | 0 | N/A | 46/204 (22.6, 17.0–28.9) |

| Male | 23.8 (8.2–47.2) | 29.7 (20.6–40.2) | 23.9 (15.4–34.1) | 48.2 (28.7–68.1) | 33.3 (0.8–90.6) | 50.0 (1.3–98.7) | 0 | 0 | 68/236 (22.8, 23.1–35.1) | |

| Undet. | 0 | 50.0 (6.8–93.2) | 44.4 (13.7–78.8) | 0 | N/A | 27.3 (6.0–61.0) | N/A | N/A | 7/29 (24.1, 10.3–43.54) | |

| Overall | 8/45 (17.8, 8.0–32.1) | 42/167 (25.2, 18.8–32.4) | 44/156 (28.2, 21.3–36.0) | 20/73 (27.4, 17.6–39.1) | 4/8 (50.0, 15.7–84.3) | 5/15 (33.3, 11.8–61.6) | 0/4 | 0/1 | 123/469 (26.2, 22.3–30.5) | |

| Genotype Type | Prevalence Rate of Genotype Type in Cardiac Tissue (95% CI) | Prevalence Rate of Genotype Type in Neural Tissue (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Genotype 1 | Apodemus agrarius 6.8% (95% CI = 1.4–18.7) Apodemus flavicollis 5.5% (95% CI = 2.2–11.0) Clethrionomys glareolus 19.4% (95% CI = 13.0–27.3) Microtus agrestis 50.0% (95% CI = 15.7–84.3) Microtus arvalis 16.4% (95% CI = 8.8–27.0) Micromys minutus 33.3% (95% CI = 11.8–61.6) | Apodemus agrarius 13.8% (95% CI = 3.9–31.7) Apodemus flavicollis 17.0% (95% CI = 11.5–23.7) Clethrionomys glareolus 9.7% (95% CI = 5.3–16.0) Microtus arvalis 12.1% (95% CI = 5.0–23.3) |

| Genotype 30 | Apodemus flavicollis 0.8% (95% CI = 0.0–4.3) | — |

| Genotype 34 | Clethrionomys glareolus 0.8% (95% CI = 0.0–4.2) | — |

| Genotype 35 | Microtus arvalis 1.4% (95% CI = 0.0–7.4) | Apodemus flavicollis 1.3% (95% CI = 0.2–4.5) |

| Genotype 36 | — | Apodemus agrarius 3.5% (95% CI = 0.1–17.8) |

| Genotype 37 | Apodemus agrarius 2.3% (95% CI = 0.1–12.0) | — |

| Genotype 38 | Apodemus flavicollis 0.8% (95% CI = 0.0–4.3) | — |

| Genotype 39 | Clethrionomys glareolus 0.8% (95% CI = 0.0–4.2) | — |

| Genotype 40 | Clethrionomys glareolus 0.8% (95% CI = 0.0–4.2) | — |

| Genotype 41 | Clethrionomys glareolus 0.8% (95% CI = 0.0–4.2) | — |

| Genotype 42 | Microtus arvalis 1.4% (95% CI = 0.0–7.4) | — |

| Genotype 43 | Apodemus flavicollis 0.8% (95% CI = 0.0–4.3) | — |

| Genotype 44 | — | Clethrionomys glareolus 0.8% (95% CI = 0.0–4.2) |

| Genotype 45 | — | Microtus arvalis 1.7% (95% CI = 0.0–9.2) |

| Genotype 46 | — | Apodemus flavicollis 1.3% (95% CI = 0.6–3.5) |

| Genotype 47 | — | Apodemus flavicollis 1.3% (95% CI = 0.6–3.5) |

| Genotype 48 | — | Clethrionomys glareolus 0.8% (95% CI = 0.0–4.2) |

| Genotype 49 | Clethrionomys glareolus 0.8% (95% CI = 0.0–4.2) | — |

| Genotype 50 | Apodemus flavicollis 0.8% (95% CI = 0.0–4.3) | — |

| Sample | n | h | S | K | Hd ± SD | π ± SD | Tajima D |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 239 | 51 | 63 | 0.63313 | 0.313 ± 0.036 | 0.00268 ± 0.00042 | −2.80712 *** |

| Europe | 132 | 19 | 22 | 0.36294 | 0.281 ± 0.052 | 0.00152 ± 0.00034 | −2.58347 *** |

| Asia | 68 | 24 | 38 | 1.88060 | 0.565 ± 0.074 | 0.00790 ± 0.00150 | 0.00790 *** |

| Americas | 92 | 11 | 10 | 0.23865 | 0.167 ± 0.053 | 0.00101 ± 0.00038 | −2.27301 ** |

| Brazil | 73 | 9 | 10 | 0.27397 | 0.184 ± 0.061 | 0.00115 ± 0.00046 | −2.32423 ** |

| China | 9 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | N/A |

| Iraq | 54 | 22 | 36 | 2.28372 | 0.631 ± 0.079 | 0.00956 ± 0.00179 | −2.70545 *** |

| USA | 18 | 3 | 2 | 0.11111 | 0.111 ± 0.096 | 0.00047 ± 0.00040 | −1.16467 |

| Overall Lithuania | 127 | 19 | 22 | 0.37720 | 0.291 ± 0.054 | 0.00158 ± 0.00035 | −2.58664 *** |

| Apodemus agrarius heart | 5 | 2 | 1 | 0.400 | 0.400 ± 0.237 | 0.00167 ± 0.00099 | −0.81650 |

| Apodemus agrarius brain | 5 | 2 | 1 | 0.400 | 0.400 ± 0.237 | 0.00167 ± 0.00099 | −0.81650 |

| Apodemus flavicollis heart | 11 | 5 | 6 | 1.09091 | 0.618 ± 0.164 | 0.00456 ± 0.00187 | −1.85059 * |

| Apodemus flavicollis brain | 31 | 4 | 3 | 0.25376 | 0.243 ± 0.099 | 0.00106 ± 0.00046 | −1.54377 |

| Clethrionomys glareolus heart | 30 | 6 | 6 | 0.40000 | 0.310 ± 0.109 | 0.00167 ± 0.00068 | −2.09995 * |

| Clethrionomys glareolus brain | 15 | 3 | 2 | 0.26667 | 0.257 ± 0.142 | 0.00112 ± 0.00064 | −1.49051 |

| Microtus agrestis heart | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | N/A |

| Microtus arvalis heart | 14 | 3 | 2 | 0.28571 | 0.275 ± 0.148 | 0.00120 ± 0.00068 | −1.48074 |

| Microtus arvalis brain | 15 | 3 | 2 | 0.26667 | 0.257 ± 0.142 | 0.00112 ± 0.00064 | −1.49051 |

| Micromys minutus heart | 5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | N/A |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Šidlauskas, G.; Gudiškis, N.; Bagdonaitė, D.L.; Rudaitytė-Lukošienė, E.; Juozaitytė-Ngugu, E.; Jasiulionis, M.; Balčiauskas, L.; Butkauskas, D.; Prakas, P. Evidence of Toxoplasma gondii in Neural and Cardiac Tissues of Wild Rodents in Lithuania. Pathogens 2025, 14, 1252. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121252

Šidlauskas G, Gudiškis N, Bagdonaitė DL, Rudaitytė-Lukošienė E, Juozaitytė-Ngugu E, Jasiulionis M, Balčiauskas L, Butkauskas D, Prakas P. Evidence of Toxoplasma gondii in Neural and Cardiac Tissues of Wild Rodents in Lithuania. Pathogens. 2025; 14(12):1252. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121252

Chicago/Turabian StyleŠidlauskas, Giedrius, Naglis Gudiškis, Dovilė Laisvūnė Bagdonaitė, Eglė Rudaitytė-Lukošienė, Evelina Juozaitytė-Ngugu, Marius Jasiulionis, Linas Balčiauskas, Dalius Butkauskas, and Petras Prakas. 2025. "Evidence of Toxoplasma gondii in Neural and Cardiac Tissues of Wild Rodents in Lithuania" Pathogens 14, no. 12: 1252. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121252

APA StyleŠidlauskas, G., Gudiškis, N., Bagdonaitė, D. L., Rudaitytė-Lukošienė, E., Juozaitytė-Ngugu, E., Jasiulionis, M., Balčiauskas, L., Butkauskas, D., & Prakas, P. (2025). Evidence of Toxoplasma gondii in Neural and Cardiac Tissues of Wild Rodents in Lithuania. Pathogens, 14(12), 1252. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121252