Implementation of Poliovirus Containment in Poliovirus Designated Facilities—United States, 2017–2024

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

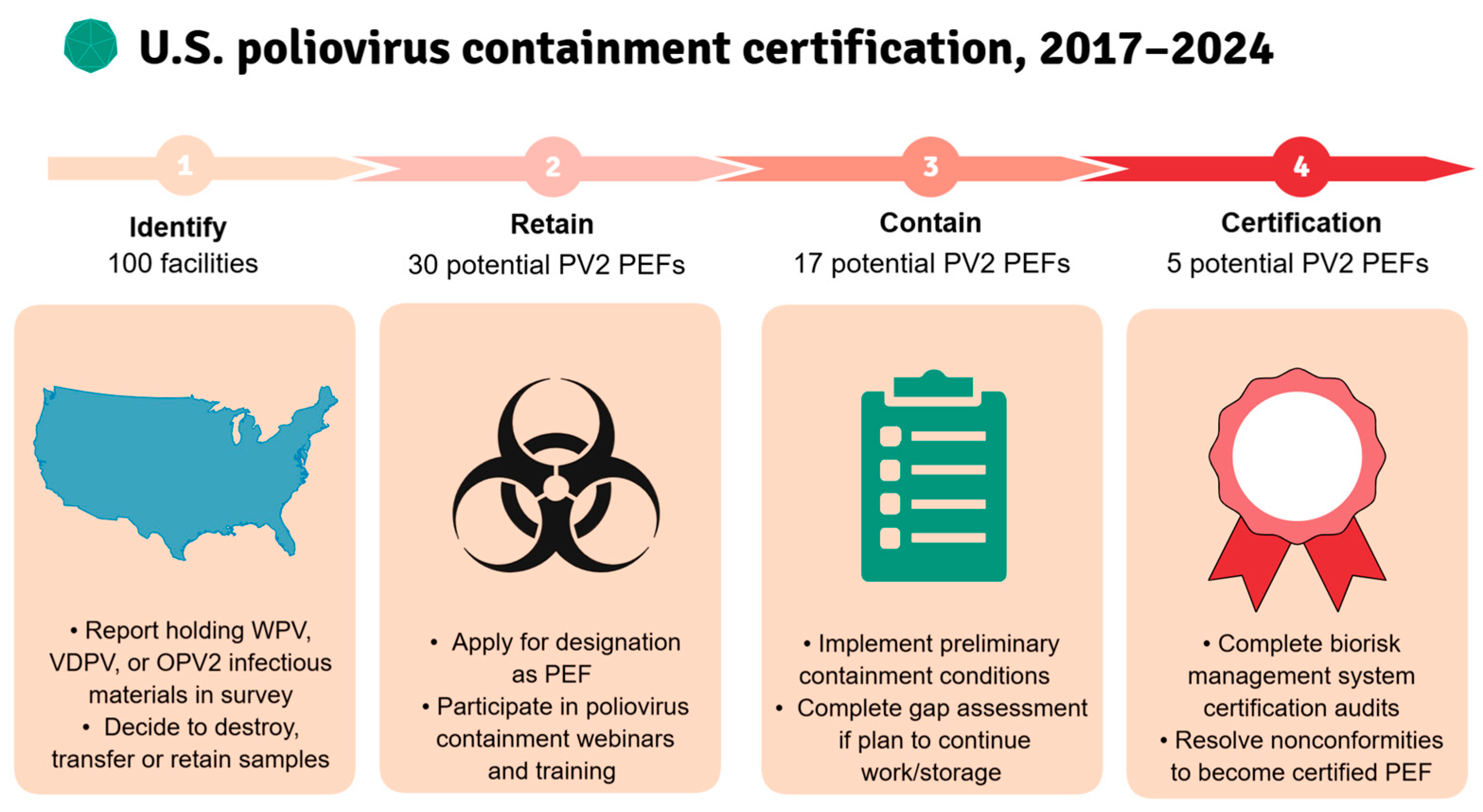

2.1. Facilities Retaining Poliovirus Materials

2.2. PEF Applications and Certification Goal

2.3. Training

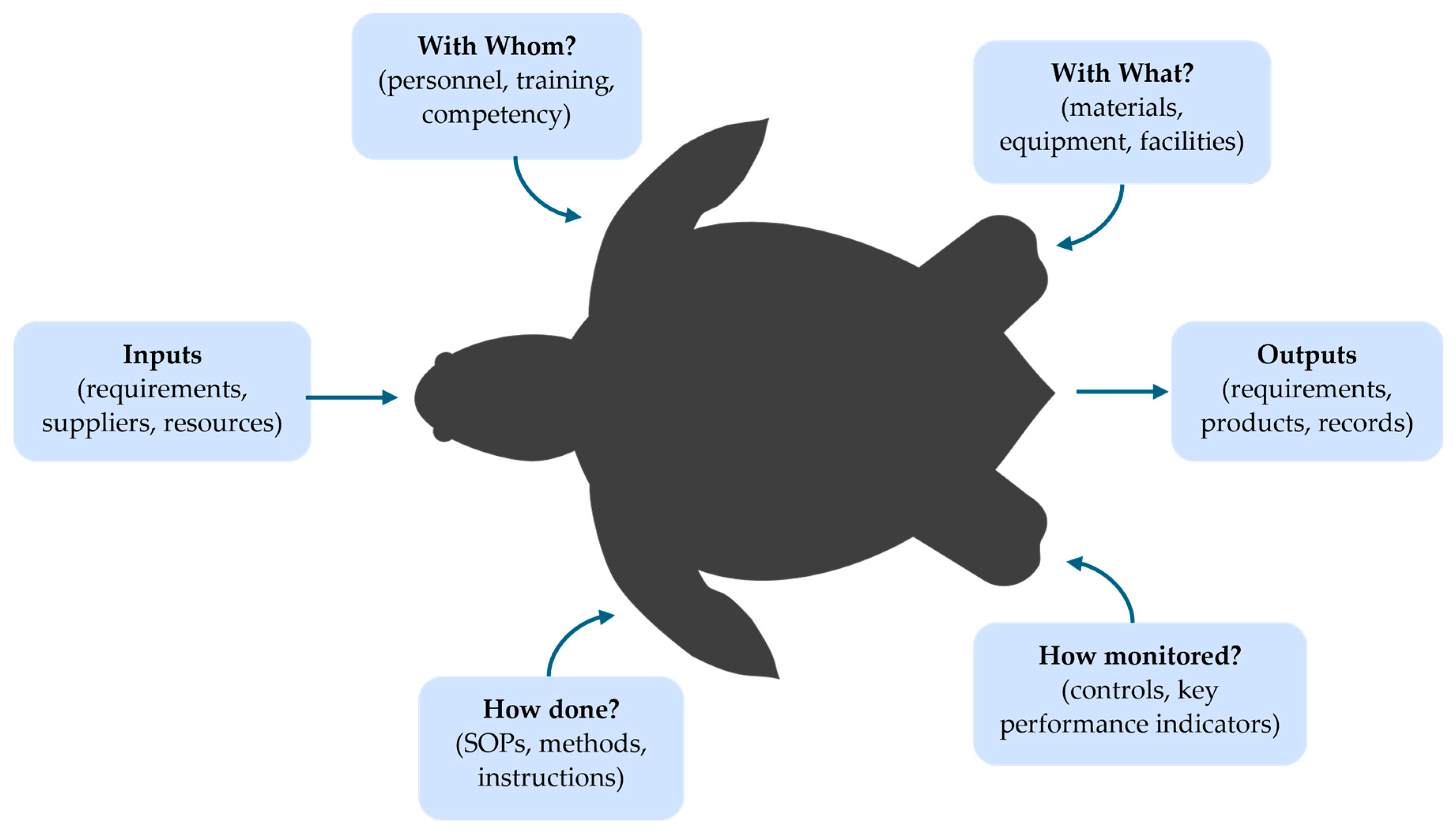

2.4. Poliovirus Containment Standard—Elements

2.5. US Poliovirus Containment Policy and Guidance

2.6. Poliovirus Containment Certification Audits

2.7. PEF Certification

2.8. Information Collection

2.9. Data Analysis

3. Results

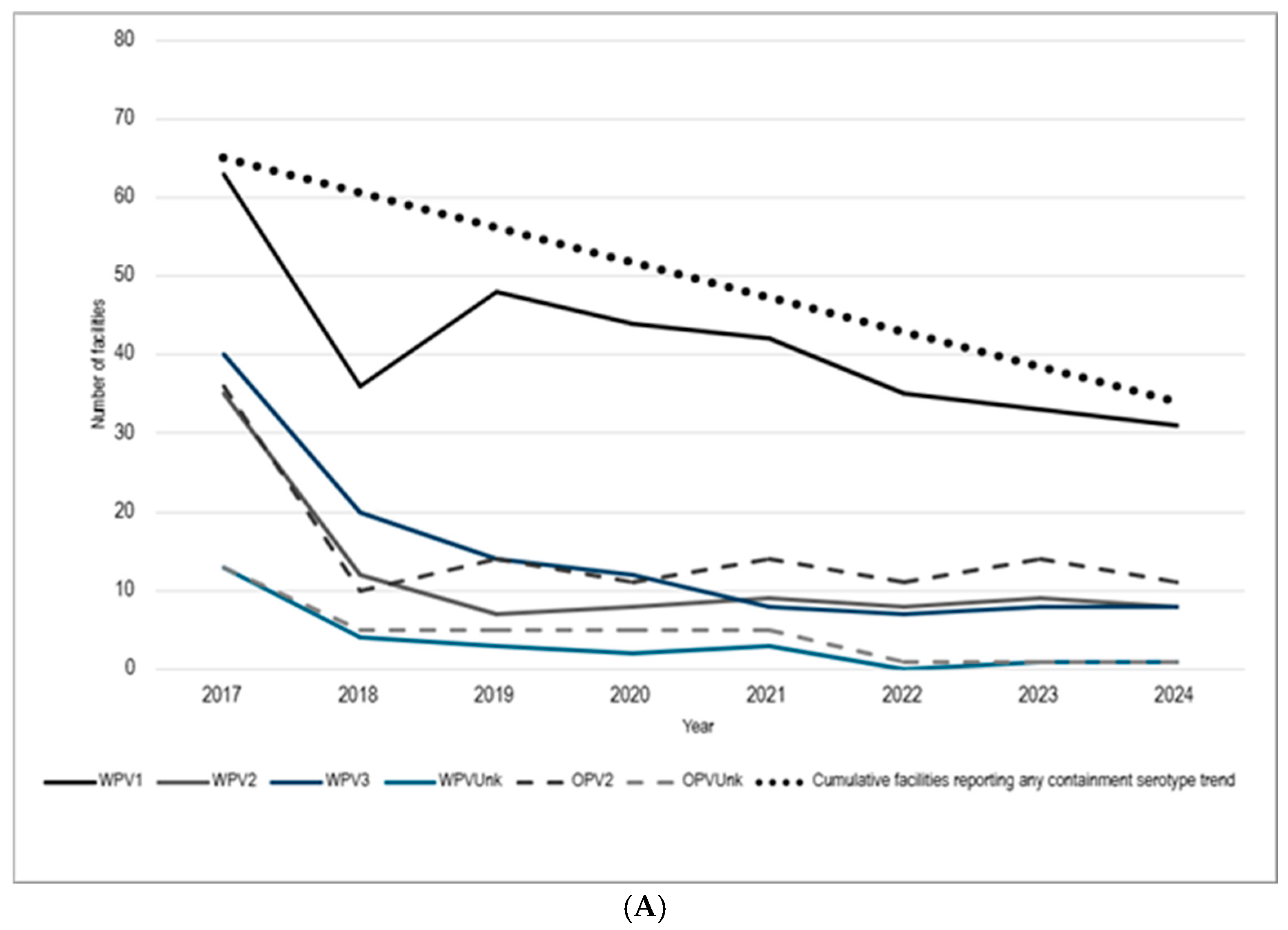

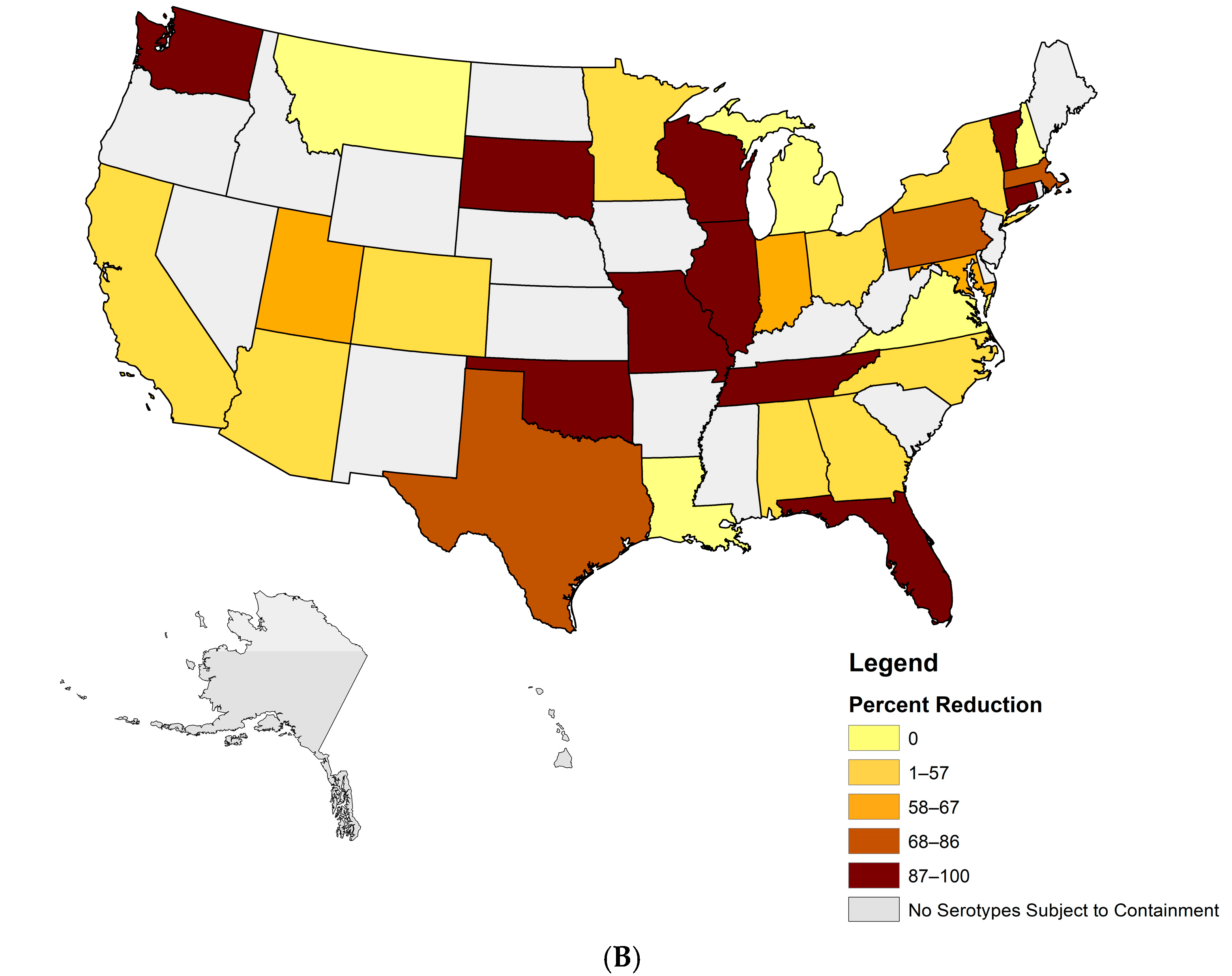

3.1. Facilities Retaining Poliovirus Materials

3.2. PEF Applications and Certification Goal

3.3. Training

3.4. Poliovirus Containment Standard—Elements and Audits

3.4.1. GAPIII Elements and Audits

3.4.2. GAPIV Elements and Audits

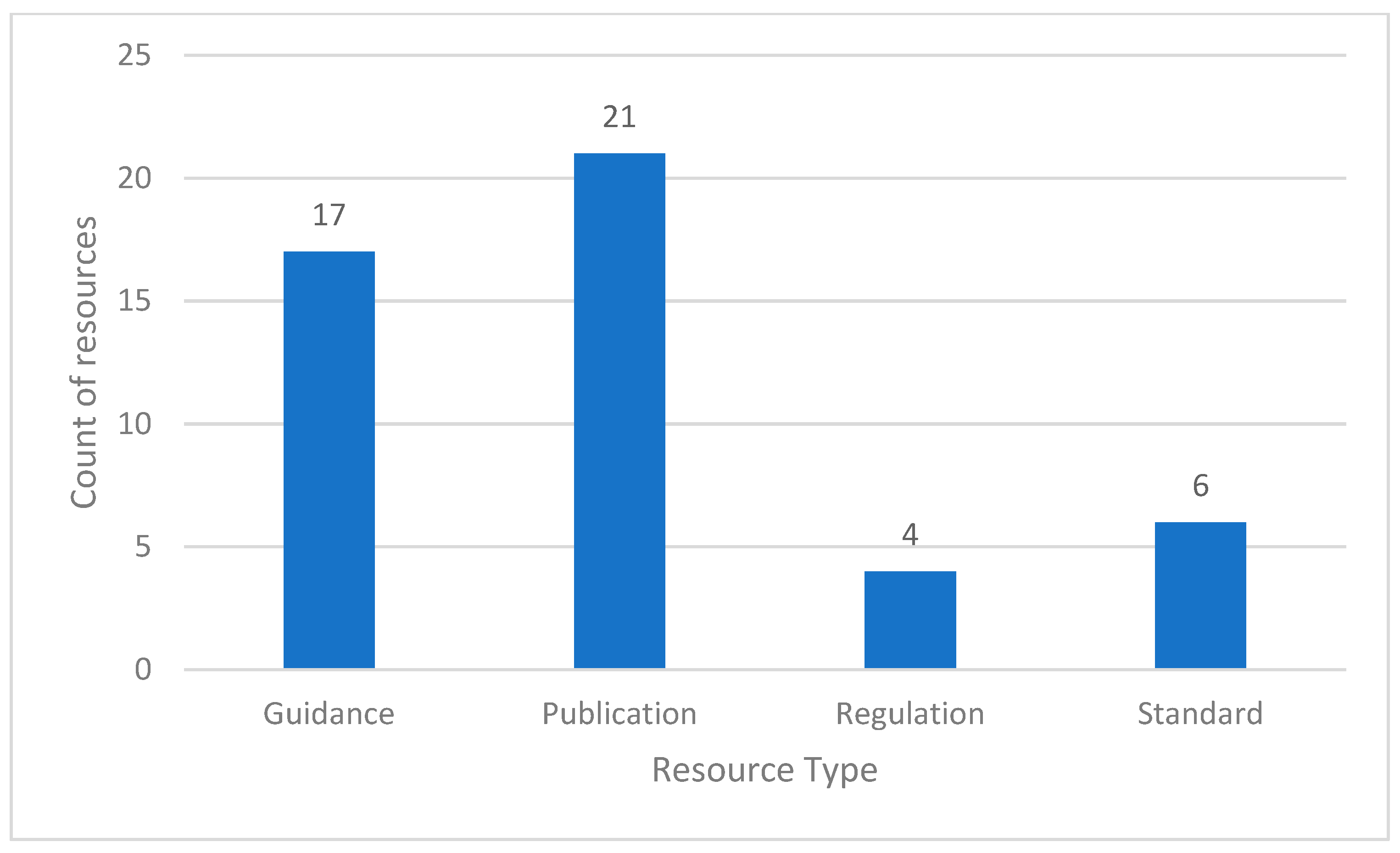

3.5. US Poliovirus Containment Policy and Guidance

3.6. PEF Certification Decision

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CAPA | Corrective action preventative action |

| CP | Certificate of Participation |

| GAP | Global action plan for poliovirus containment |

| GPEI | Global Polio Eradication Initiative |

| ICC | Interim Certificate of Containment |

| ISO | International Organization for Standardization |

| NC | Nonconformance |

| NPDES | National pollutant discharge elimination system |

| OPV | Oral polio vaccine |

| PEF | Poliovirus-essential facility |

| PDCA | Plan–do–check–act |

| PIM | Potentially infectious material |

| RCA | Root cause analysis |

| VDPV | Vaccine-derived poliovirus |

| WPV | Wild poliovirus |

References

- Geiger, K.; Stehling-Ariza, T.; Bigouette, J.P.; Bennett, S.D.; Burns, C.C.; Quddus, A.; Wassilak, S.G.F.; Bolu, O. Progress Toward Poliomyelitis Eradication—Worldwide, January 2022–December 2023. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2024, 73, 441–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moffett, D.B.; Llewellyn, A.; Singh, H.; Saxentoff, E.; Partridge, J.; Boualam, L.; Pallansch, M.; Wassilak, S.; Asghar, H.; Roesel, S.; et al. Progress Toward Poliovirus Containment Implementation—Worldwide, 2019–2020. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2020, 69, 1330–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandyopadhyay, A.S.; Singh, H.; Fournier-Caruana, J.; Modlin, J.F.; Wenger, J.; Partridge, J.; Sutter, R.W.; Zaffran, M.J. Facility-Associated Release of Polioviruses into Communities-Risks for the Posteradication Era. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2019, 25, 1363–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkes, N. Smallpox death in Britain challenges presumption of laboratory safety. Science 1979, 203, 855–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jezek, Z.; Khodakevich, L.N.; Wickett, J.F. Smallpox and its post-eradication surveillance. Bull. World Health Organ. 1987, 65, 425–434. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. WHO Global Action Plan for Laboratory Containment of Wild Polioviruses; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. WHO Global Action Plan to Minimize Poliovirus Facility-Associated Risk After Type-Specific Eradication of Wild Polioviruses and Sequential Cessation of Oral Polio Vaccine Use—GAPIII, 3rd ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hampton, L.M.; Farrell, M.; Ramirez-Gonzalez, A.; Menning, L.; Shendale, S.; Lewis, I.; Rubin, J.; Garon, J.; Harris, J.; Hyde, T.; et al. Cessation of Trivalent Oral Poliovirus Vaccine and Introduction of Inactivated Poliovirus Vaccine—Worldwide, 2016. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2016, 65, 934–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottendorfer, C.; Shelby, B.; Sanders, C.A.; Llewellyn, A.; Myrick, C.; Brown, C.; Suppiah, S.; Gustin, K.; Smith, L.H. Establishment of a Poliovirus Containment Program and Containment Certification Process for Poliovirus-Essential Facilities, United States 2017–2022. Pathogens 2024, 13, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CWA 15793:2008; Laboratory Biorisk Management Standard. CEN: Brussels, Belgium, 2008.

- ISO35001:2019; Biorisk Management for Laboratories and Other Related Organisations. International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

- World Health Organization. WHO Global Action Plan for Poliovirus Containment—GAPIV, 4th ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Country Progress Towards Poliovirus Containment Certification. 2025. Available online: https://polioeradication.org/what-we-do-2/containment/ (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Honeywood, M.J.; Jeffries-Miles, S.; Wong, K.; Harrington, C.; Burns, C.C.; Oberste, M.S.; Bowen, M.D.; Vega, E. Use of guanidine thiocyanate-based nucleic acid extraction buffers to inactivate poliovirus in potentially infectious materials. J. Virol. Methods 2021, 297, 114262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI). Global Poliovirus Containment Action Plan 2022–2024; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- ISO9001:2015; Quality Management Systems—Requirements. International Organization of Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2015.

- ISO/IEC TS 17021; ISO/IEC TS 17021-1:2015 Conformity Assessment—Requirements for Bodies Providing Audit and Certification of Management Systems. International Organization of Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015.

- ISO19011:2018; Guidelines for Auditing Management Systems. International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

- ISO 45001:2018; Occupational Health and Safety Management Systems—Requirements with Guidance for Use. International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

- Oberste, M.S. Progress of polio eradication and containment requirements after eradication. Transfusion 2018, 58 (Suppl. 3), 3078–3083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Accreditation Forum. Determination of Audit Time of Quality, Environmental, and Occupational Health & Safety Management Systems; International Accreditation Forum: Cherrybrook, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Prevots, D.R.; Burr, R.K.; Sutter, R.W.; Murphy, T.V.; Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. Poliomyelitis prevention in the United States. Updated recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm. Rep. 2000, 49, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Polio Vaccination Coverage Among Children 19–35 Months by State, HHS Region, and the United States, National Immunization Survey-Child (NIS-Child), 1995 Through 2021. 2022. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/imz-managers/coverage/childvaxview/interactive-reports/index.html (accessed on 6 March 2025).

- United States Environmental Protection Agency (US EPA). Clean Water Act, Federal Water Pollution Control Amendments. 1972. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/laws-regulations/summary-clean-water-act (accessed on 6 March 2025).

- United States Environmental Protection Agency (US EPA). NPDES Municipal Wastewater Program. 2024. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/npdes/municipal-wastewater (accessed on 6 March 2025).

- SAS Institute Inc. SAS Software, version 9.4; SAS Institute Inc.: Cary, NC, USA, 2020.

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Biosafety in Microbiological and Biomedical Laboratories (BMBL), 6th ed.; 2020. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/labs/media/pdfs/2025/08/SF__19a_308133-A_BMBL6_00-BOOK-WEB-final-3.pdf (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- World Health Organization. Summary Report from the Twenty-Fourth Meeting of the Global Commission for Certification of Poliomyelitis Eradication; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Marcet, P.L.; Short, B.; Deas, A.; Sun, H.; Harrington, C.; Shaukat, S.; Alam, M.M.; Baba, M.; Faneye, A.; Namuwulya, P.; et al. Advancing poliovirus eradication: Lessons learned from piloting direct molecular detection of polioviruses in high-risk and priority geographies. Microbiol. Spectr. 2025, 13, e0227924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namageyo-Funa, A.; Greene, S.A.; Henderson, E.; Traore, M.A.; Shaukat, S.; Bigouette, J.P.; Jorba, J.; Wiesen, E.; Bolu, O.; Diop, O.M.; et al. Update on Vaccine-Derived Poliovirus Outbreaks—Worldwide, January 2023–June 2024. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2024, 73, 909–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huseynov, S.; Saxentoff, E.; Diedrich, S.; Martin, J.; Wieczorek, M.; Cabrerizo, M.; Blomqvist, S.; Jorba, J.; Hagan, J. Notes from the Field: Detection of Vaccine-Derived Poliovirus Type 2 in Wastewater—Five European Countries, September-December 2024. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2025, 74, 122–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, N.; Grobusch, M.P.; Jokelainen, P.; Wyllie, A.L.; Barac, A.; Mora-Rillo, M.; Gkrania-Klotsas, E.; Pellejero-Sagastizabal, G.; Pano-Pardo, J.R.; Duizer, E.; et al. Poliomyelitis in Gaza. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2025, 31, 154–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. World Health Assembly Resolution 71.16: Poliomyelitis—Containment of Polioviruses. 2018. Available online: https://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA71/A71_R16-en.pdf (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Jeannoel, M.; Antona, D.; Lazarus, C.; Lina, B.; Schuffenecker, I. Risk Assessment and Virological Monitoring Following an Accidental Exposure to Concentrated Sabin Poliovirus Type 3 in France, November 2018. Vaccines 2020, 8, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duizer, E.; Ruijs, W.L.; Putri Hintaran, A.D.; Hafkamp, M.C.; van der Veer, M.; Te Wierik, M.J. Wild poliovirus type 3 (WPV3)-shedding event following detection in environmental surveillance of poliovirus essential facilities, the Netherlands, November 2022 to January 2023. Euro Surveill. 2023, 28, 2300049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Government Publishing Office. Electronic Code of Federal Regulations Title 42 Chapter 1 Subchapter F Part 73. 2025. Available online: https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-42/chapter-I/subchapter-F/part-73 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). National laboratory inventory for global poliovirus containment—United States, November 2003. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2004, 53, 457–459. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). National laboratory inventory for global poliovirus containment—European Region, June 2006. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2006, 55, 916–918. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Completion of national laboratory inventories for wild poliovirus containment—Region of the Americas, March 2010. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2010, 59, 985–988. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). National laboratory inventories for wild poliovirus containment—Western Pacific region, 2008. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2009, 58, 975–978. [Google Scholar]

- Previsani, N.; Tangermann, R.H.; Tallis, G.; Jafari, H.S. World Health Organization Guidelines for Containment of Poliovirus Following Type-Specific Polio Eradication—Worldwide, 2015. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2015, 64, 913–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bassey, B.E.; Braka, F.; Shuaib, F.; Banda, R.; Tegegne, S.G.; Ticha, J.M.; Abdullalhi, W.H.; Kolawole, O.M.; Kabir, Y. Distribution pattern of poliovirus potentially infectious materials in the phase 1b medical laboratories containment in conformity with the global action plan III. BMC Public Health 2018, 18 (Suppl. 4), 1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Seventy Fifth World Health Assembly: Poliomyelitis: Poliomyelitis Eradication Report. 2022. Available online: https://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA75/A75_23-en.pdf (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Mbaeyi, C.; Ul Haq, A.; Safdar, R.M.; Khan, Z.; Corkum, M.; Henderson, E.; Wadood, Z.M.; Alam, M.M.; Franka, R. Progress Toward Poliomyelitis Eradication—Pakistan, January 2023–June 2024. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2024, 73, 788–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, C.M.; Rathee, M.; Chaudhury, S.; Wadood, M.Z.; Ather, F.; Henderson, E.; Martinez, M. Progress Toward Poliomyelitis Eradication—Afghanistan, January 2023–September 2024. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2024, 73, 1129–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Government White House. Withdrawing the United States from the World Health Organization. 2025. Available online: https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2025/01/29/2025-01957/withdrawing-the-united-states-from-the-world-health-organization (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Sundqvist, B.; Bengtsson, U.A.; Wisselink, H.J.; Peeters, B.P.; van Rotterdam, B.; Kampert, E.; Bereczky, S.; Johan Olsson, N.G.; Szekely Bjorndal, A.; Zini, S.; et al. Harmonization of European laboratory response networks by implementing CWA 15793: Use of a gap analysis and an “insider” exercise as tools. Biosecur. Bioterror. 2013, 11 (Suppl. 1), S36–S44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritterson, R.; Kingston, L.; Fleming, A.E.J.; Lauer, E.; Dettmann, R.A.; Casagrande, R. A Call for a National Agency for Biorisk Management. Health Secur. 2022, 20, 187–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dettmann, R.A.; Ritterson, R.; Lauer, E.; Casagrande, R. Concepts to Bolster Biorisk Management. Health Secur. 2022, 20, 376–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callihan, D.R.; Downing, M.; Meyer, E.; Ochoa, L.A.; Petuch, B.; Tranchell, P.; White, D. Considerations for Laboratory Biosafety and Biosecurity During the Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pandemic: Applying the ISO 35001:2019 Standard and High-Reliability Organizations Principles. Appl. Biosaf. 2021, 26, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rengarajan, K. The implementation of a biorisk management system (CWA 15793:2008) and process improvement using an A/BSL-3 research project as a model system. In Proceedings of the 56th Annual Biosafety and Biosecurity Conference, Kansas City, MO, USA, 17–23 October 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kembi, F. Biorisk Management Implementation in Select Public Health Laboratories Across the U.S. In Proceedings of the 67th Annual Biosafety and Biosecurity Conference, Phoenix, AZ, USA, 1–6 November 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Lestari, F.; Kadir, A.; Miswary, T.; Maharani, C.F.; Bowolaksono, A.; Paramitasari, D. Implementation of Bio-Risk Management System in a National Clinical and Medical Referral Centre Laboratories. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, T.; Phyu, S.; Se-Thoe, S.Y.; Chu, J.J.H. Biorisk Management for SARS-CoV-2 Research in a Biosafety Level-3 Core Facility. Methods Mol. Biol. 2022, 2452, 441–464. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Appelt, S.; Jacob, D.; Rohleder, A.M.; Brave, A.; Szekely Bjorndal, A.; Di Caro, A.; Grunow, R.; Joint Action EMERGE laboratory network. Assessment of biorisk management systems in high containment laboratories, 18 countries in Europe, 2016 and 2017. Euro Surveill. 2020, 25, 2000089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Virus Type | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PEF Characteristics a | b PV2, WPV3/VDPV3 | WPV1/VDPV1 | ||

| N = 25 | Number (n = 5) | Percent (%) | Number (n = 20) | Percent (%) |

| Facility Type | ||||

| Academic | 1 | 20 | 11 | 55 |

| Commercial | 2 | 40 | 7 | 35 |

| Government | 2 | 40 | 2 | 10 |

| Work Types(s)c | ||||

| Research d | 3 | 60 | 15 | 75 |

| Vaccine Production | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Clinical Trials | 2 | 40 | 2 | 10 |

| Animal Model | 1 | 20 | 4 | 20 |

| Diagnostics | 2 | 40 | 1 | 5 |

| QC Testing e | 1 | 20 | 6 | 30 |

| Environmental | - | - | 1 | 5 |

| Storage Only | 1 | 20 | 0 | 0 |

| Laboratory Design f | ||||

| A/BSL-2 d | 0 | 0 | 14 | 70 |

| A/BSL-3 | 4 | 80 | 6 | 30 |

| A/BSL-4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Not Applicable (Repository) | 1 | 20 | 0 | 0 |

| Certification Goal | ||||

| Certificate of Participation (CP) | - | - | 14 | 70 |

| Interim Certificate of Containment (ICC) | 1 | 20 | 0 | 0 |

| Certificate of Containment (CC) | 4 | 80 | 6 | 30 |

| Element | Audit Category 1 | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count of Nonconformance Clauses Found | Count of Clauses Assessed | Proportion of Nonconformance Clauses Per Element (%) | ||||||||||||||

| Gap Assessment (n = 10) | ICC Stage 1 (n = 3) | ICC Stage 2 (n = 3) | Gap Assessment (n = 10) | ICC Stage 1 (n = 3) | ICC Stage 2 (n = 3) | Gap Assessment | ICC Stage 1 | ICC Stage 2 | ||||||||

| 1 Biorisk management system | 217 | 72 | 29 | 345 | 151 | 162 | 62.9 | 47.7 | 17.9 | |||||||

| 2 Risk assessment | 46 | 10 | 9 | 62 | 23 | 27 | 74.2 | 43.5 | 33.3 | |||||||

| 3 Inventory | 27 | 5 | 3 | 39 | 15 | 15 | 69.2 | 33.3 | 20.0 | |||||||

| 4 General safety | 6 | 2 | 1 | 8 | 3 | 3 | 75.0 | 66.7 | 33.3 | |||||||

| 5 Personnel and competency | 37 | 9 | 2 | 60 | 27 | 27 | 61.7 | 33.3 | 7.4 | |||||||

| 6 Good microbiological technique | 6 | 3 | 0 | 15 | 6 | 6 | 40.0 | 50.0 | 0.0 | |||||||

| 7 Clothing and PPE | 7 | 4 | 2 | 16 | 6 | 6 | 43.8 | 66.7 | 33.3 | |||||||

| 8 Human factors | 5 | 1 | 0 | 7 | 3 | 3 | 71.4 | 33.3 | 0.0 | |||||||

| 9 Health care | 25 | 6 | 1 | 45 | 18 | 17 | 55.6 | 33.3 | 5.9 | |||||||

| 10 Emergency response | 32 | 13 | 5 | 56 | 23 | 24 | 57.1 | 56.5 | 20.8 | |||||||

| 11 Accident/incident investigation | 5 | 3 | 1 | 7 | 3 | 3 | 71.4 | 100.0 | 33.3 | |||||||

| 12 Physical facility | 100 | 25 | 9 | 213 | 72 | 72 | 46.9 | 34.7 | 12.5 | |||||||

| 13 Equipment and maintenance | 34 | 7 | 3 | 35 | 15 | 15 | 97.1 | 46.7 | 20.0 | |||||||

| 14 Decontamination | 20 | 7 | 5 | 23 | 12 | 12 | 87.0 | 58.3 | 41.7 | |||||||

| 15 Transport | 8 | 2 | 0 | 8 | 3 | 3 | 100.0 | 66.7 | 0.0 | |||||||

| 16 Security | 22 | 12 | 0 | 43 | 21 | 21 | 51.2 | 57.1 | 0.0 | |||||||

| Key (%): | 0 | 10 | 20 | 30 | 40 | 50 | 60 | 70 | 80 | 90 | 100 | |||||

| Element (n) a | Number of Nonconformance Clauses Found b | Number of Clauses Assessed | Proportion of Nonconformance Clauses Per Element (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Biorisk Management System (1) | 81 | 263 | 30.8 |

| 2 | Risk Assessment and Control (1) | 37 | 55 | 67.3 |

| 3 | Worker Health Program (0) | 16 | 30 | 53.3 |

| 4 | Competence and Training (1) | 21 | 45 | 46.7 |

| 5 | Good Microbiological Practice/Procedure (2) | 6 | 16 | 37.5 |

| 6 | Clothing and PPE (0) | 6 | 8 | 75.0 |

| 7 | Security (0) | 10 | 35 | 28.6 |

| 8 | Facility Physical Requirements (7) c | 46 | 152 | 30.3 |

| 9 | Equipment and Maintenance (1) | 6 | 10 | 60.0 |

| 10 | Poliovirus Inventory and Information (5) | 10 | 40 | 25.0 |

| 11 | Waste Management/Decontamination (4) | 26 | 42 | 61.9 |

| 12 | Transport Procedures (1) | 3 | 9 | 33.3 |

| 13 | Emergency Response/Contingency Plan (0) | 16 | 40 | 40.0 |

| 14 | Accident/Incident Investigation (0) | 3 | 5 | 60.0 |

| US NAC Policy Area | Count Policy Area Citations a (n = 70) | Proportion Policy Area Citations (%) | Time in Effect (Months) | Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Security | 15 | 21.4 | 60 | 0.25 |

| Biorisk Management System and Risk Assessment | 15 | 21.4 | 44 | 0.34 |

| Emergency Response and Exposure Management Plans | 8 | 11.4 | 12 | 0.67 |

| Inactivation | 7 | 10 | 30 | 0.23 |

| Inventory | 6 | 8.6 | 60 | 0.10 |

| Storage Outside of Containment | 5 | 7.1 | 60 | 0.08 |

| Occupational Health | 5 | 7.1 | 12 | 0.42 |

| PPE and Hand Hygiene Practices | 4 | 5.7 | 51 | 0.08 |

| Shared Use of Space | 3 | 4.3 | 44 | 0.07 |

| Transfer | 2 | 2.9 | 60 | 0.03 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ottendorfer, C.; Vander Kelen, P.; Sanders, C.A.; Watson, E.; Suppiah, S.; Hoffman, W.; Sinclair, C.; Marfo, A.; Haynes Smith, L. Implementation of Poliovirus Containment in Poliovirus Designated Facilities—United States, 2017–2024. Pathogens 2025, 14, 1250. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121250

Ottendorfer C, Vander Kelen P, Sanders CA, Watson E, Suppiah S, Hoffman W, Sinclair C, Marfo A, Haynes Smith L. Implementation of Poliovirus Containment in Poliovirus Designated Facilities—United States, 2017–2024. Pathogens. 2025; 14(12):1250. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121250

Chicago/Turabian StyleOttendorfer, Christy, Patrick Vander Kelen, Cecelia A. Sanders, Emily Watson, Suganthi Suppiah, William Hoffman, Colby Sinclair, Abena Marfo, and Lia Haynes Smith. 2025. "Implementation of Poliovirus Containment in Poliovirus Designated Facilities—United States, 2017–2024" Pathogens 14, no. 12: 1250. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121250

APA StyleOttendorfer, C., Vander Kelen, P., Sanders, C. A., Watson, E., Suppiah, S., Hoffman, W., Sinclair, C., Marfo, A., & Haynes Smith, L. (2025). Implementation of Poliovirus Containment in Poliovirus Designated Facilities—United States, 2017–2024. Pathogens, 14(12), 1250. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121250