IL-5 and IP-10 Detected in Quantiferon Supernatants Distinguish Latent Tuberculosis from Healthy Individuals in Areas with High Burden in Lima, Peru

Abstract

1. Introduction

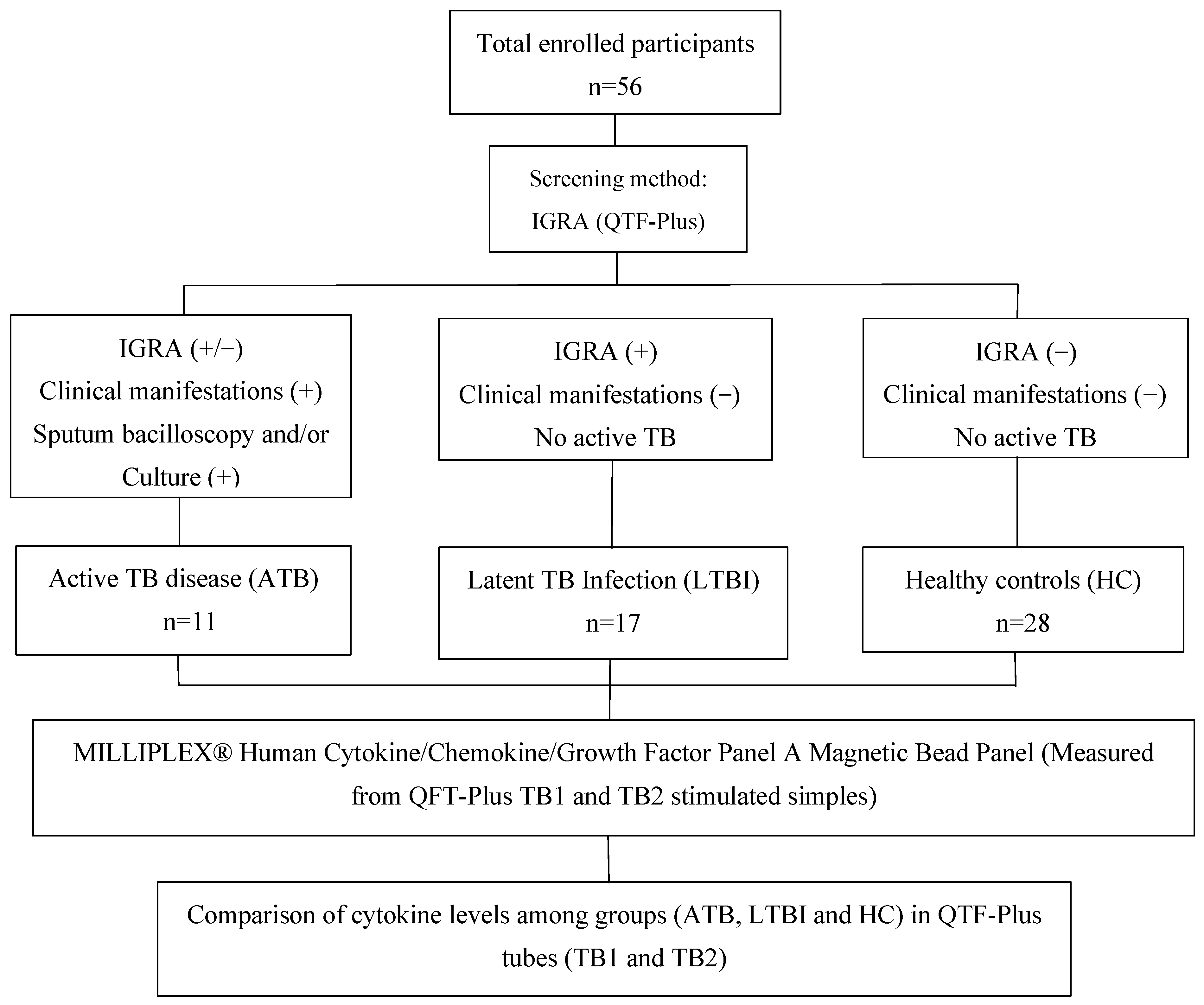

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection and Enrolled Population

2.2. QuantiFERON-TB GOLD In-Tube Assay

2.3. Multiplex Cytokine Analysis

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics of Study Participants

3.2. Plasma Cytokine Profile and Its Dynamic Response to Change in Tuberculosis Infection

3.3. Identification of Cytokine to Distinguish ATB and LTBI Subjects from Healthy Controls

3.4. Accuracy of Each Cytokine Marker in the QFT TB1 and TB2 Tubes for Discriminating Between LTBI and HC Groups

3.5. Accuracy of Each Cytokine Marker in the QFT TB1 and TB2 Tubes for Discriminating Between ATB and HC Groups

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Global Tuberculosis Report [Internet]. 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/global-programme-on-tuberculosis-and-lung-health/tb-reports/global-tuberculosis-report-2024 (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Yumpo-Castañeda, D.H. Prevalencia de tuberculosis latente en estudiantes de medicina. Rev. Soc. Peru Med. Interna 2018, 31, 125–127. [Google Scholar]

- Soto Cabezas, M.G.; Munayco Escate, C.V.; Chávez Herrera, J.; López Romero, S.L.; Moore, D. Prevalencia de infección tuberculosa latente en trabajadores de salud de establecimientos del primer nivel de atención. Lima, Perú. Rev. Peru Med. Exp. Salud Publica 2017, 34, 649–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jilani, T.N.; Avula, A.; Zafar Gondal, A.; Siddiqui, A.H. Active Tuberculosis. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK513246/ (accessed on 26 June 2025).

- Carranza, C.; Pedraza-Sanchez, S.; de Oyarzabal-Mendez, E.; Torres, M. Diagnosis for Latent Tuberculosis Infection: New Alternatives. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.H. Tuberculosis Infection and Latent Tuberculosis. Tuberc. Respir. Dis. 2016, 79, 201–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pai, M.; Kalantri, S.; Dheda, K. New tools and emerging technologies for the diagnosis of tuberculosis: Part I. Latent tuberculosis. Expert Rev. Mol. Diagn. 2006, 6, 413–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CDC Tuberculosis (TB). Clinical Testing Guidance for Tuberculosis: Interferon Gamma Release Assay. 2024. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/tb/hcp/testing-diagnosis/interferon-gamma-release-assay.html (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Mack, U.; Migliori, G.B.; Sester, M.; Rieder, H.L.; Ehlers, S.; Goletti, D.; Bossink, A.; Magdorf, K.; Hölscher, C.; Kampmann, B.; et al. LTBI: Latent tuberculosis infection or lasting immune responses to M. tuberculosis? A TBNET consensus statement. Eur. Respir. J. 2009, 33, 956–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frahm, M.; Goswami, N.D.; Owzar, K.; Hecker, E.; Mosher, A.; Cadogan, E.; Nahid, P.; Ferrari, G.; Stout, J.E. Discriminating between latent and active tuberculosis with multiple biomarker responses. Tuberc. Edinb. Scotl. 2011, 91, 250–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Wang, S.; Lu, C.; Shao, L.; Gao, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Huang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, W. Multiple cytokine responses in discriminating between active tuberculosis and latent tuberculosis infection. Tuberculosis 2017, 102, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biraro, I.A.; Egesa, M.; Kimuda, S.; Smith, S.G.; Toulza, F.; Levin, J.; Joloba, M.; Katamba, A.; Cose, S.; Dockrell, H.M.; et al. Effect of isoniazid preventive therapy on immune responses to mycobacterium tuberculosis: An open label randomised, controlled, exploratory study. BMC Infect. Dis. 2015, 15, 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chegou, N.N.; Black, G.F.; Kidd, M.; van Helden, P.D.; Walzl, G. Host markers in QuantiFERON supernatants differentiate active TB from latent TB infection: Preliminary report. BMC Pulm. Med. 2009, 9, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chegou, N.N.; Detjen, A.K.; Thiart, L.; Walters, E.; Mandalakas, A.M.; Hesseling, A.C.; Walzl, G. Utility of Host Markers Detected in Quantiferon Supernatants for the Diagnosis of Tuberculosis in Children in a High-Burden Setting. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e64226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wergeland, I.; Assmus, J.; Dyrhol-Riise, A.M. Cytokine Patterns in Tuberculosis Infection; IL-1ra, IL-2 and IP-10 Differentiate Borderline QuantiFERON-TB Samples from Uninfected Controls. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0163848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzukawa, M.; Akashi, S.; Nagai, H.; Nagase, H.; Nakamura, H.; Matsui, H.; Hebisawa, A.; Ohta, K. Combined Analysis of IFN-γ, IL-2, IL-5, IL-10, IL-1RA and MCP-1 in QFT Supernatant Is Useful for Distinguishing Active Tuberculosis from Latent Infection. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0152483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Won, E.J.; Choi, J.H.; Cho, Y.N.; Jin, H.M.; Kee, H.J.; Park, Y.W.; Kwon, Y.S.; Kee, S.J. Biomarkers for discrimination between latent tuberculosis infection and active tuberculosis disease. J. Infect. 2017, 74, 281–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Liu, W.; Ye, Z.; Zheng, C.; Ge, S. Multiplex analysis of plasma cytokines/chemokines showing different immune responses in active TB patients, latent TB infection and healthy participants. Tuberculosis 2017, 107, 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teklu, T.; Kwon, K.; Wondale, B.; HaileMariam, M.; Zewude, A.; Medhin, G.; Legesse, M.; Pieper, R.; Ameni, G. Potential Immunological Biomarkers for Detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis Infection in a Setting Where M. tuberculosis Is Endemic, Ethiopia. Infect. Immun. 2018, 86, 10-1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Yang, Z.; Wu, F.; Ge, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Li, D.; Gao, M.; Liu, X. Multiple cytokine analysis based on QuantiFERON-TB gold plus in different tuberculosis infection status: An exploratory study. BMC Infect. Dis. 2024, 24, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera, M.; Keynan, Y.; Lopez, L.; Marín, D.; Vélez, L.; McLaren, P.J.; Rueda, Z.V. Cytokine/chemokine profiles in people with recent infection by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1129398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Shaukat, S.N.; Eugenin, E.; Nasir, F.; Khanani, R.; Kazmi, S.U. Identification of immune biomarkers in recent active pulmonary tuberculosis. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 11481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yang, Z.; Ge, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, M.; Liu, X.; Zhang, L. Specific Cytokines Analysis Incorporating Latency-Associated Antigens Differentiates Mycobacterium tuberculosis Infection Status: An Exploratory Study. Infect. Drug Resist. 2024, 17, 3385–3393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hong, J.Y.; Jung, G.S.; Kim, H.; Kim, Y.M.; Lee, H.J.; Cho, S.N.; Kim, S.K.; Chang, J.; Kang, Y.A. Efficacy of inducible protein 10 as a biomarker for the diagnosis of tuberculosis. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2012, 16, e855–e859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marczewska, A.; Wojciechowska, C.; Marczewski, K.; Gospodarczyk, N.; Dolibog, P.; Czuba, Z.; Wróbel, K.; Zalejska-Fiolka, J. Elevated Levels of IL–1Ra, IL–1β, and Oxidative Stress in COVID-19: Implications for Inflammatory Pathogenesis. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 2489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, J.W.; Huang, Y.S.; Tang, H.Y.; Bi, J.; Liu, Y.F.; Wang, Y.D. Flt3/Flt3L Participates in the Process of Regulating Dendritic Cells and Regulatory T Cells in DSS-Induced Colitis. Gastroenterol. Res. Pract. 2014, 2014, 483578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, A.; Singh, V.K.; Actor, J.K.; Hunter, R.L.; Jagannath, C.; Subbian, S.; Khan, A. GM-CSF Dependent Differential Control of Mycobacterium tuberculosis Infection in Human and Mouse Macrophages: Is Macrophage Source of GM-CSF Critical to Tuberculosis Immunity? Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Li, Y.; Wei, C.; Li, Y.; Xu, H.; Wu, Y.; Jia, Y.; Guo, R.; Jia, J.; Qi, X.; et al. The meta-analysis for ideal cytokines to distinguish the latent and active TB infection. BMC Pulm. Med. 2020, 20, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Etna, M.P.; Giacomini, E.; Severa, M.; Coccia, E.M. Pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines in tuberculosis: A two-edged sword in TB pathogenesis. Semin. Immunol. 2014, 26, 543–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandiarajan, A.N.; Kumar, N.P.; Selvaraj, N.; Ahamed, S.F.; Viswanathan, V.; Thiruvengadam, K.; Hissar, S.; Shanmugam, S.; Bethunaickan, R.; Nott, S.; et al. Distinct TB-antigen stimulated cytokine profiles as predictive biomarkers for unfavorable treatment outcomes in pulmonary tuberculosis. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1392256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajamanickam, A.; Ann Daniel, E.; Dasan, B.; Thiruvengadam, K.; Chandrasekaran, P.; Gaikwad, S.; Pattabiraman, S.; Bhanu, B.; Sivaprakasam, A.; Kulkarni, V.; et al. Plasma Immune Biomarkers Predictive of Progression to Active Tuberculosis in Household Contacts of Patients With Tuberculosis. J. Infect. Dis. 2025, 231, 696–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wergeland, I.; Pullar, N.; Assmus, J.; Ueland, T.; Tonby, K.; Feruglio, S.; Kvale, D.; Damås, J.K.; Aukrust, P.; Mollnes, T.E.; et al. IP-10 differentiates between active and latent tuberculosis irrespective of HIV status and declines during therapy. J. Infect. 2015, 70, 381–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapulana, A.M.; Mpotje, T.; Baiyegunhi, O.O.; Ndlovu, H.; Smit, T.K.; McHugh, T.D.; Marakalala, M.J. Combined analysis of host IFN-γ, IL-2 and IP-10 as potential LTBI biomarkers in ESAT-6/CFP10 stimulated blood. Front. Mol. Med. 2024, 4, 1345510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, B.M.F.; Rangel, F.; Andrade, A.M.S.; Daniel, E.A.; Figueiredo, M.C.; Staats, C.; Rolla, V.C.; Kritski, A.L.; Cordeiro-Santos, M.; Gupta, A.; et al. Predictive Markers of Incident Tuberculosis in Close Contacts in Brazil and India. J. Infect. Dis. 2025, 232, 567–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, H.; Zhou, J.; Yang, Q.; Yang, Y.; Zhou, F.; Qian, M.; Lin, X.; Zhang, W.; Shao, L.; Ruan, Q. QuantiFERON-TB supernatant-based biomarkers predicting active tuberculosis progression. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2025, 157, 107915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchez, C.; Jaramillo-Valverde, L.; Capristano, S.; Solis, G.; Soto, A.; Valdivia-Silva, J.; Poterico, J.A.; Guio, H. Antigen-Induced IL-1RA Production Discriminates Active and Latent Tuberculosis Infection. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Prestileo, T.; Pipitone, G.; Sanfilippo, A.; Ficalora, A.; Natoli, G.; Corrao, S.; Immigrant Take Care Advocacy Team. Tuberculosis among Migrant Populations in Sicily: A Field Report. J. Trop. Med. 2021, 2021, 7856347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Type | Cytokines/Chemokines |

|---|---|

| Proinflammatory cytokines | CD40L, IFN-α, IFN-γ, IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-3, IL-5, IL-6, IL-9, IL-12 (p40), IL-12 (p70), IL-17α, TNF-α, TNF-β |

| Anti-inflammatory cytokines | IL-1RA, IL-4, IL-10, IL-13 |

| Chemokines | Eotaxin, Fractalkine, GRO, IL-8, IP-10, MCP-1, MCP-3, MDC, MIP-1α, MIP-1β |

| Growth factors | EGF, FGF-2, Flt-3L, G-CSF, GM-CSF, IL-2, IL-3, IL-15, IL-7, VEGFA |

| ATB (%) | LTBI (%) | HC (%) | p Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 11) | (n = 17) | (n = 28) | |||

| Gender | Female | 6 (17.1) | 12 (34.3) | 17 (48.6) | 0.6671 † |

| Male | 5 (23.8) | 5 (23.8) | 11 (52.4) | ||

| Age (years) | 22–29 | 2 (22.2) | 1 (11.1) | 6 (66.7) | 0.5524 ‡ |

| 30–37 | 2 (14.3) | 3 (21.4) | 9 (64.3) | ||

| 38–45 | 3 (20.0) | 5 (33.3) | 7 (46.7) | ||

| 46 or more | 4 (22.2) | 8 (44.4) | 6 (33.3) | ||

| Ethnicity | Mestizo | 11 (20.4) | 17 (31.5) | 26 (48.1) | 0.6909 ‡ |

| White | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (100.0) | ||

| Marital status | Married | 5 (27.8) | 7 (38.9) | 6 (33.3) | 0.3711 ‡ |

| Single | 3 (15.0) | 3 (15.0) | 14 (70.0) | ||

| Cohabiting | 3 (21.4) | 5 (35.7) | 6 (42.9) | ||

| Separated | 0 (0.0) | 1 (50.0) | 1 (50.0) | ||

| Divorced | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (100.0) | ||

| Widow | 0 (0.0) | 1 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Working type | Dependent | 4 (13.8) | 8 (27.6) | 17 (58.6) | 0.528 ‡ |

| Independent | 3 (18.8) | 6 (37.5) | 7 (43.8) | ||

| House | 2 (33.3) | 2 (33.3) | 2 (33.3) | ||

| Student | 1 (33.3) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (66.7) | ||

| Eventual | 1 (50.0) | 1 (50.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Travel time by transport | Less than one hour | 6 (22.2) | 11 (40.7) | 10 (37.0) | 0.0313 ‡ |

| One hour | 3 (18.8) | 2 (12.5) | 11 (68.8) | ||

| Two hours | 0 (0.0) | 2 (22.2) | 7 (77.8) | ||

| Three hours or more | 2 (50.0) | 2 (50.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| BCG Vaccine | Yes | 9 (17.6) | 16 (31.4) | 26 (51.0) | 0.5749 ‡ |

| No | 2 (40.0) | 1 (20.0) | 2 (40.0) | ||

| QTF assay result | Positive | 7 (29.2) | 17 (70.8) | 0 (0.0) | <0.0001 ‡ |

| Negative | 1 (3.4) | 0 (0.0) | 28 (96.6) | ||

| Indeterminate | 3 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| BMI | Normal | 6 (35.3) | 5 (29.4) | 6 (35.3) | 0.6291 ‡ |

| Overweight | 4 (14.8) | 8 (29.6) | 15 (55.6) | ||

| Class I obesity | 1 (10.0) | 3 (30.0) | 6 (60.0) | ||

| Class II obesity | 0 (0.0) | 1 (50.0) | 1 (50.0) | ||

| Tube | Marker | Cut-Off (pg/mL) | Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TB1-Nil | IFN-g | 37.25 | 75 (54–96) | 87 (64–100) |

| IL-5 | 1.36 | 71 (47–95) | 90 (71–100) | |

| IP-10 | 485.79 | 84 (65–100) | 72 (51–92) | |

| FLT-3L | 3.04 | 57 (31–83) | 92 (78–100) | |

| IL-2 | 12.39 | 93 (81–100) | 91 (76–100) | |

| IL-1RA | 203.91 | 76 (56–96) | 85 (70–100) | |

| TB2-Nil | IL-5 | 1.46 | 84 (65–100) | 90 (73–100) |

| IFN-g | 57.15 | 80 (59–100) | 88 (68–100) | |

| IP-10 | 859.31 | 93 (73–100) | 76 (56–97) | |

| IL-2 | 8.04 | 94 (83–100) | 83 (62–100) | |

| IL-1RA | 270.9 | 64 (41–87) | 95 (86–100) |

| Tube | Marker | Cut-Off (pg/mL) | Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TB1-Nil | IFN-g | 29.13 | 82 (59–100) | 87 (64–100) |

| FLT-3L | 2.32 | 78 (50–100) | 76 (54–100) | |

| IL-2 | 15.93 | 100 (100–100) | 91 (76–100) | |

| IL-1RA | 221.65 | 82 (59–100) | 90 (78–100) | |

| TB2-Nil | GM-CSF | 71.32 | 86 (60–100) | 78 (51–100) |

| IL-5 | 2.21 | 88 (65–100) | 91 (74–100) | |

| IFN-g | 114.15 | 80 (55–100) | 89 (68–100) | |

| IL-2 | 49.65 | 89 (68–100) | 92 (76–100) | |

| IL-1RA | 161.73 | 91 (73–100) | 82 (66–98) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

De la Peña Galindo, N.; Valdez, S.C.; Neira, C.S.; Calderon, H.B.; Sanchez, G.S.; Pelaez, F.P.; Galarza Perez, M. IL-5 and IP-10 Detected in Quantiferon Supernatants Distinguish Latent Tuberculosis from Healthy Individuals in Areas with High Burden in Lima, Peru. Pathogens 2025, 14, 1225. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121225

De la Peña Galindo N, Valdez SC, Neira CS, Calderon HB, Sanchez GS, Pelaez FP, Galarza Perez M. IL-5 and IP-10 Detected in Quantiferon Supernatants Distinguish Latent Tuberculosis from Healthy Individuals in Areas with High Burden in Lima, Peru. Pathogens. 2025; 14(12):1225. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121225

Chicago/Turabian StyleDe la Peña Galindo, Nawal, Silvia Capristano Valdez, Cesar Sanchez Neira, Henri Bailon Calderon, Gilmer Solis Sanchez, Flor Peceros Pelaez, and Marco Galarza Perez. 2025. "IL-5 and IP-10 Detected in Quantiferon Supernatants Distinguish Latent Tuberculosis from Healthy Individuals in Areas with High Burden in Lima, Peru" Pathogens 14, no. 12: 1225. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121225

APA StyleDe la Peña Galindo, N., Valdez, S. C., Neira, C. S., Calderon, H. B., Sanchez, G. S., Pelaez, F. P., & Galarza Perez, M. (2025). IL-5 and IP-10 Detected in Quantiferon Supernatants Distinguish Latent Tuberculosis from Healthy Individuals in Areas with High Burden in Lima, Peru. Pathogens, 14(12), 1225. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121225