Specificity of Primers and Probes for Molecular Diagnosis of Leishmania (Leishmania) chagasi in Dogs and Wild Animals

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Biological Sample

- -

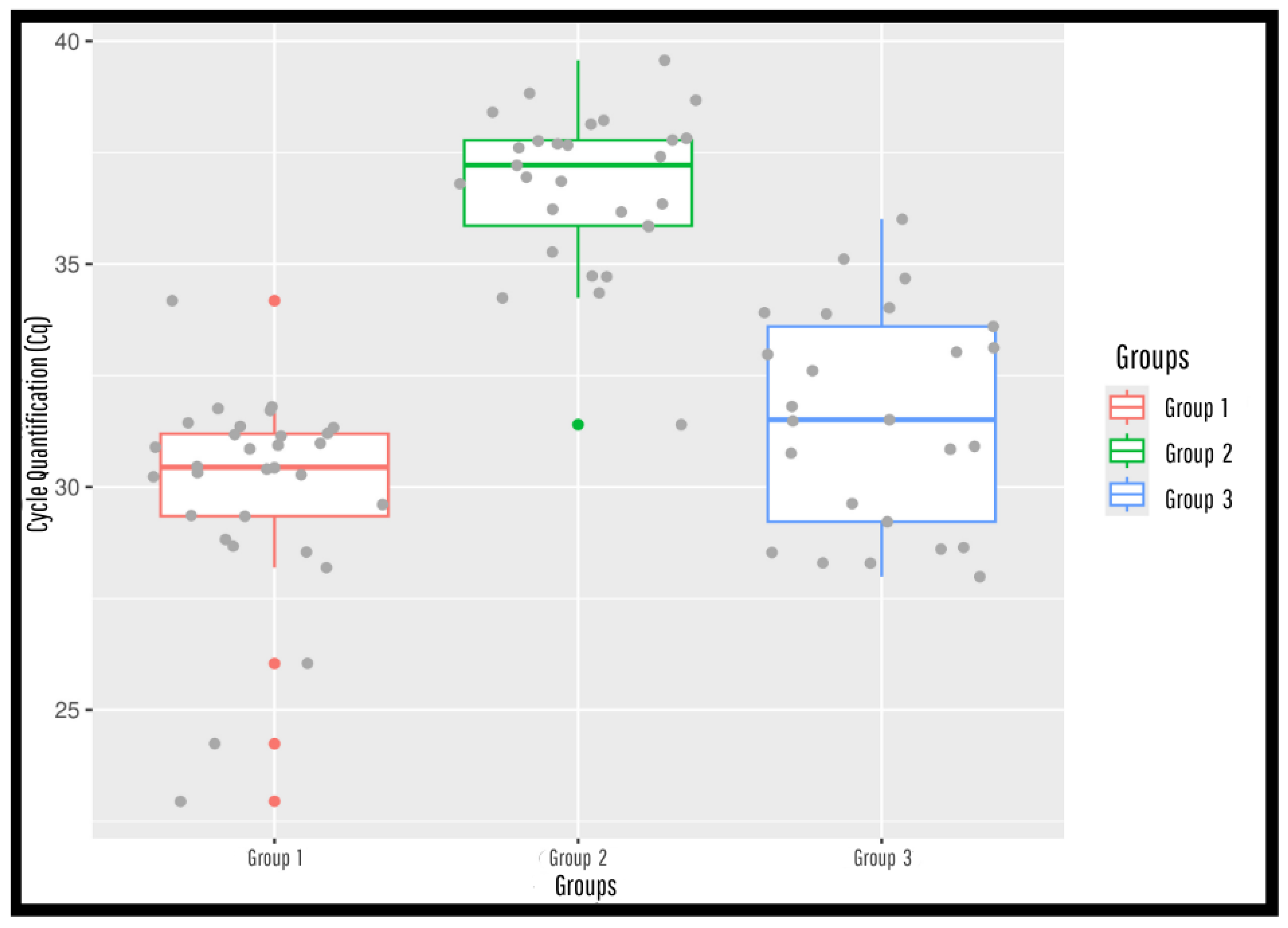

- Group 1 (n = 30): domestic dogs with positive serology, from the municipality of Barcarena, collected between 2011 and 2012 as part of the study “Prevalence of canine infection caused by Leishmania (L.) chagasi determined by PCR in lymph node aspirates”;

- -

- Group 2 (n = 30): domestic dogs with negative serology, also from Barcarena and from the same study.

- -

- Group 3 (n = 25): samples of wild animals with varying serology, collected between 2020 and 2024 in the municipalities of Parauapebas, Curionópolis, Canaã dos Carajás and Marabá. These municipalities are part of the area of influence of major mining projects in the Carajás Complex (S11D, Serra Leste, Azul and Salobo) and were included in the study “Assessment of environmental and social changes and their influence on the nosological picture”.

2.2. Indirect Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (Indirect ELISA)

2.3. Culture of Leishmania sp. Promastigostes

2.4. Deoxyribonucleic Acid (DNA) Extraction/Quantification/Quality from Serum

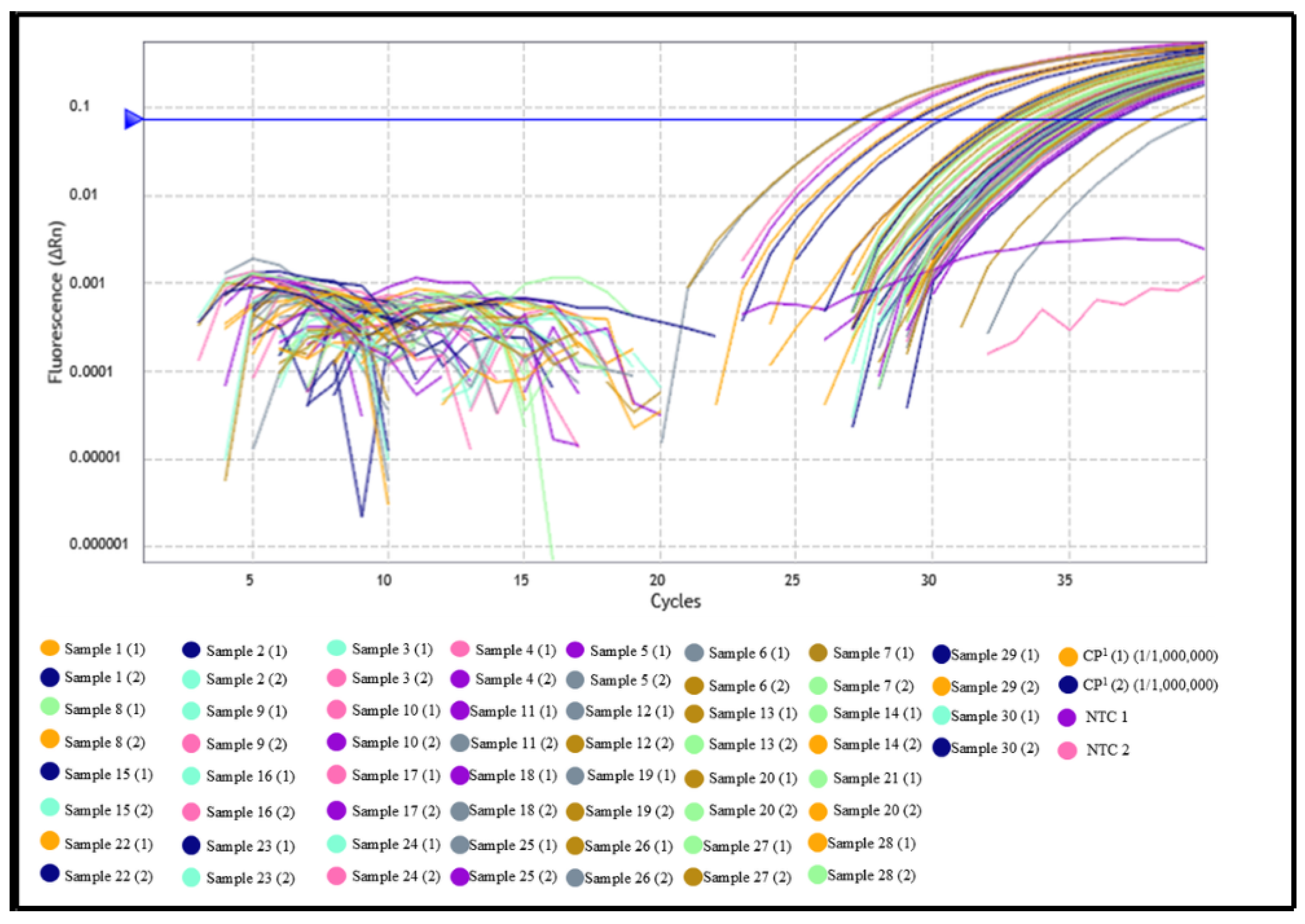

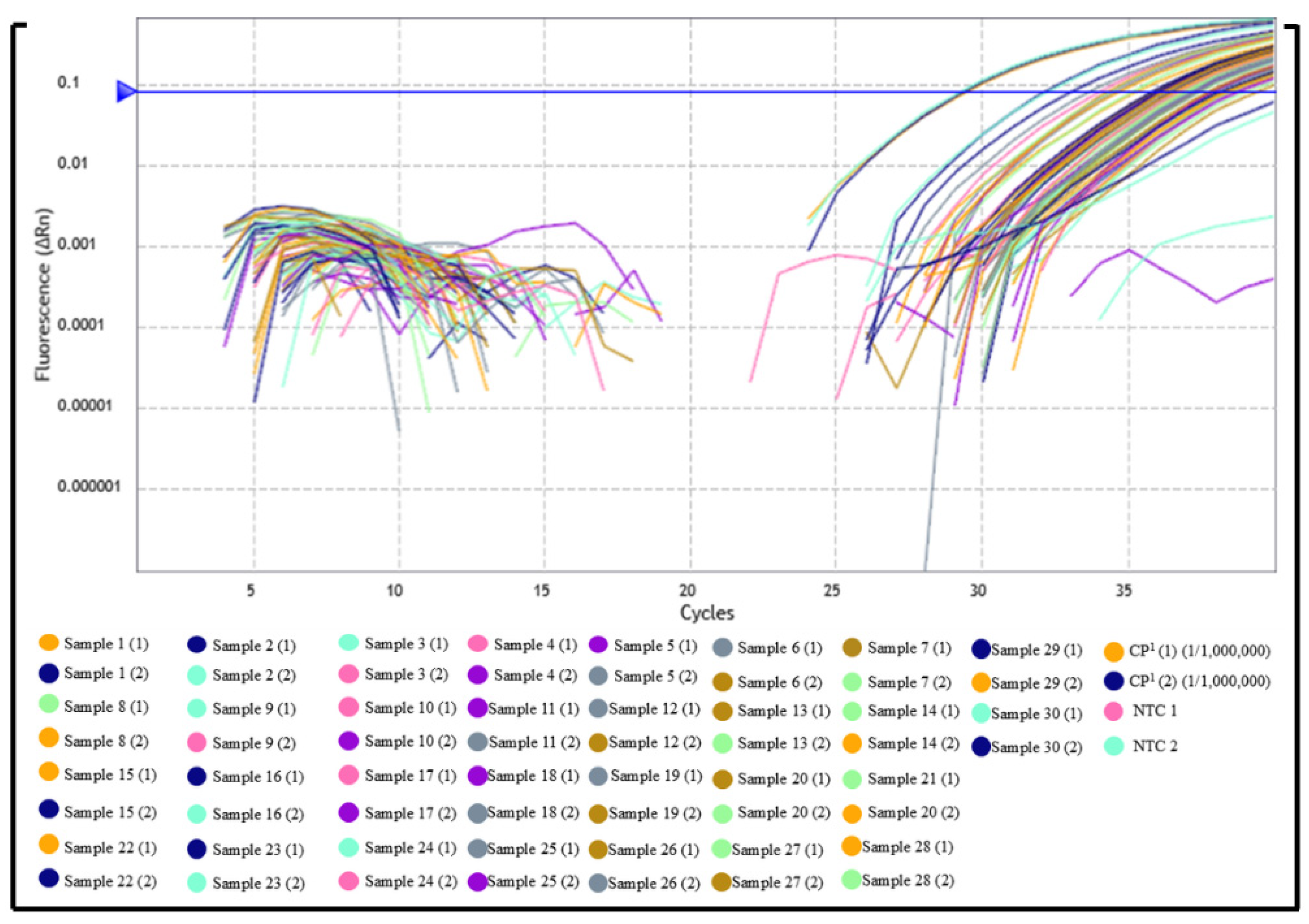

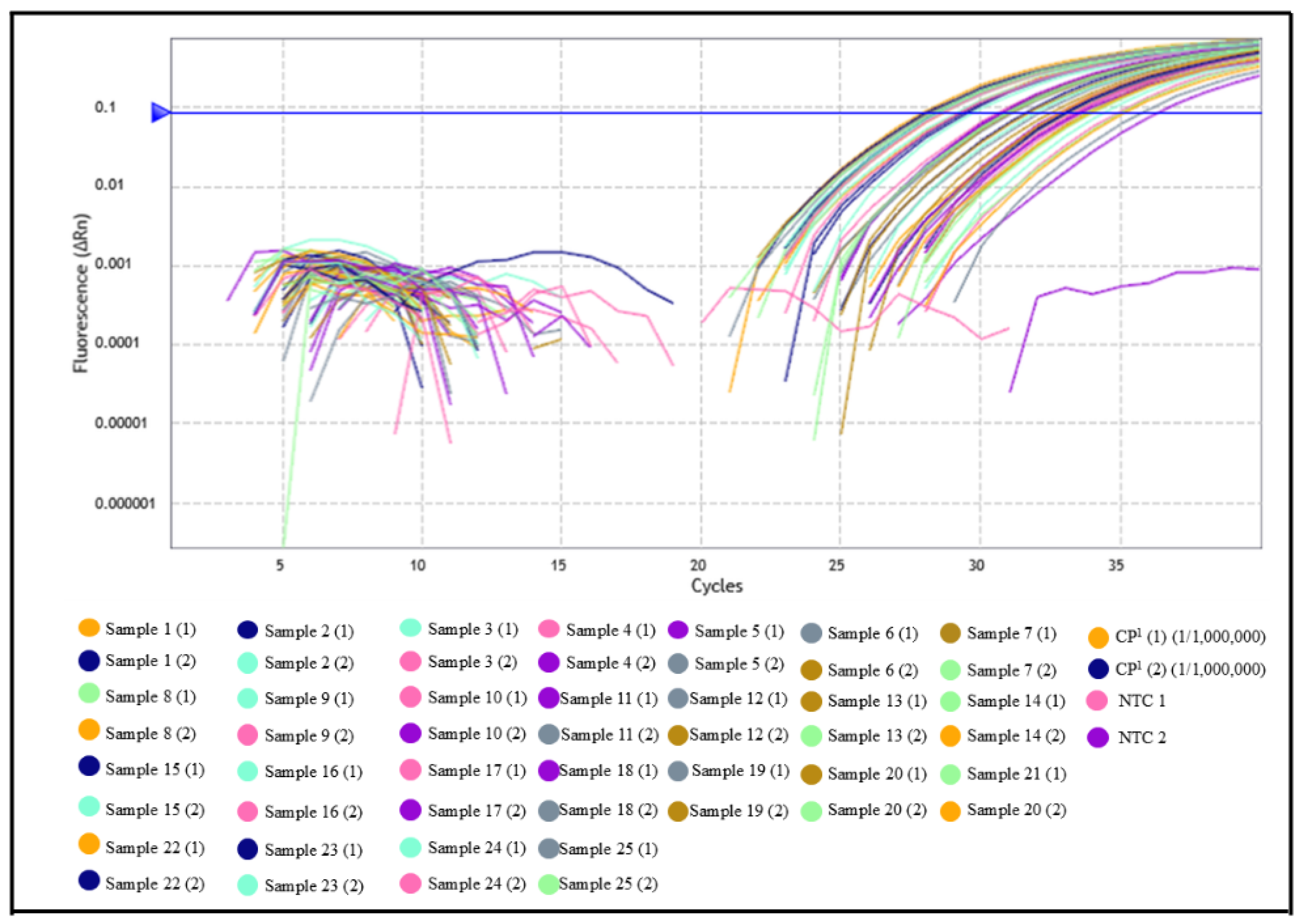

2.5. Evaluation of Serum Samples from Domestic Dogs and Wild Animals by qPCR

2.6. In Silico Analysis of Primer and Probe Molecular Structures

2.7. Data Analysis and Statistics

- Kappa < 0: disagreement

- 0 to 0.20: slight agreement

- 0.21 to 0.40: fair agreement

- 0.41 to 0.60: moderate agreement

- 0.61 to 0.80: substantial agreement

- 0.81 to 1.00: almost perfect agreement

3. Results

3.1. Evaluation of Serum Samples from Domestic Dogs and Wild Animals by Indirect ELISA and qPCR

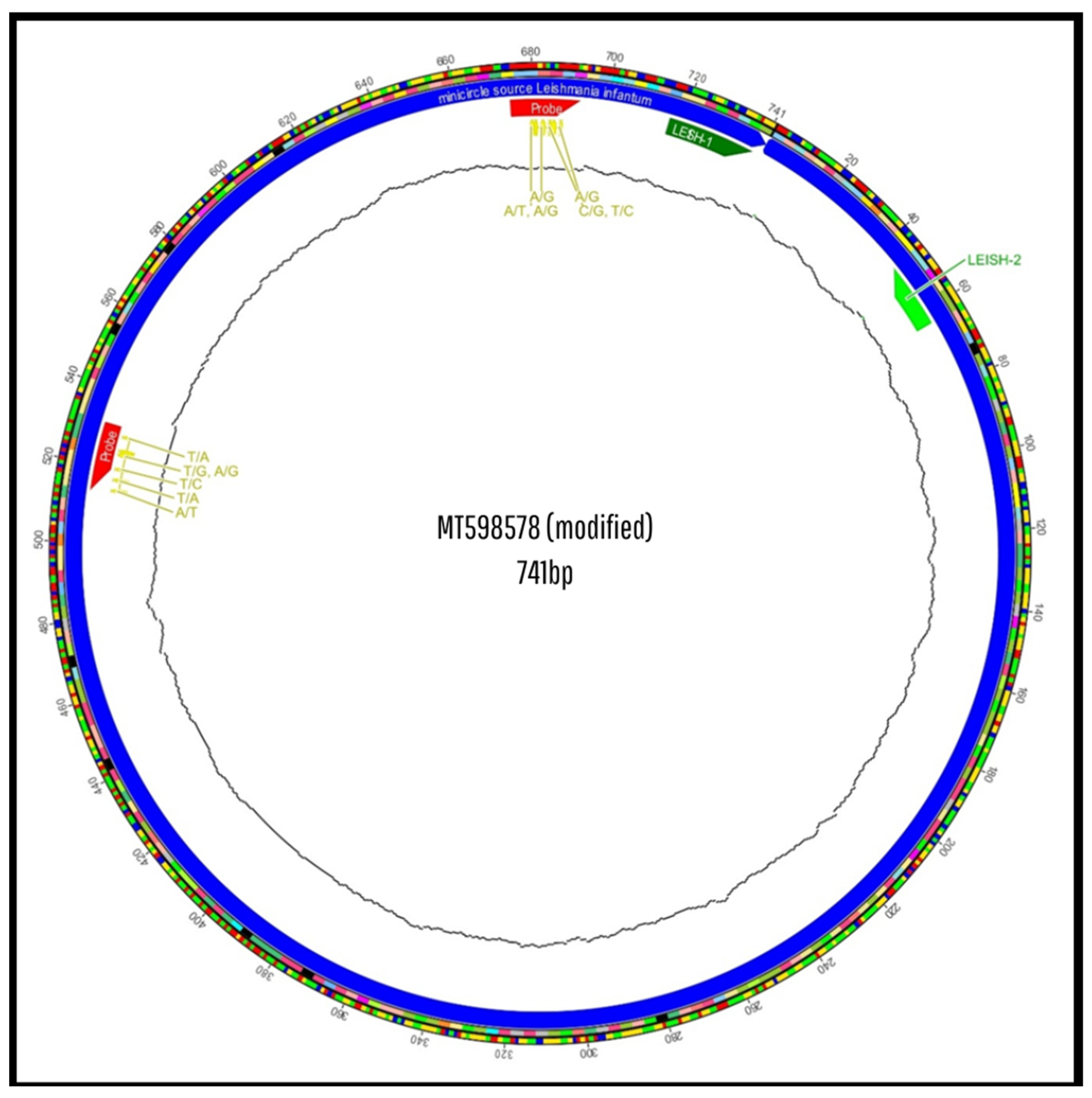

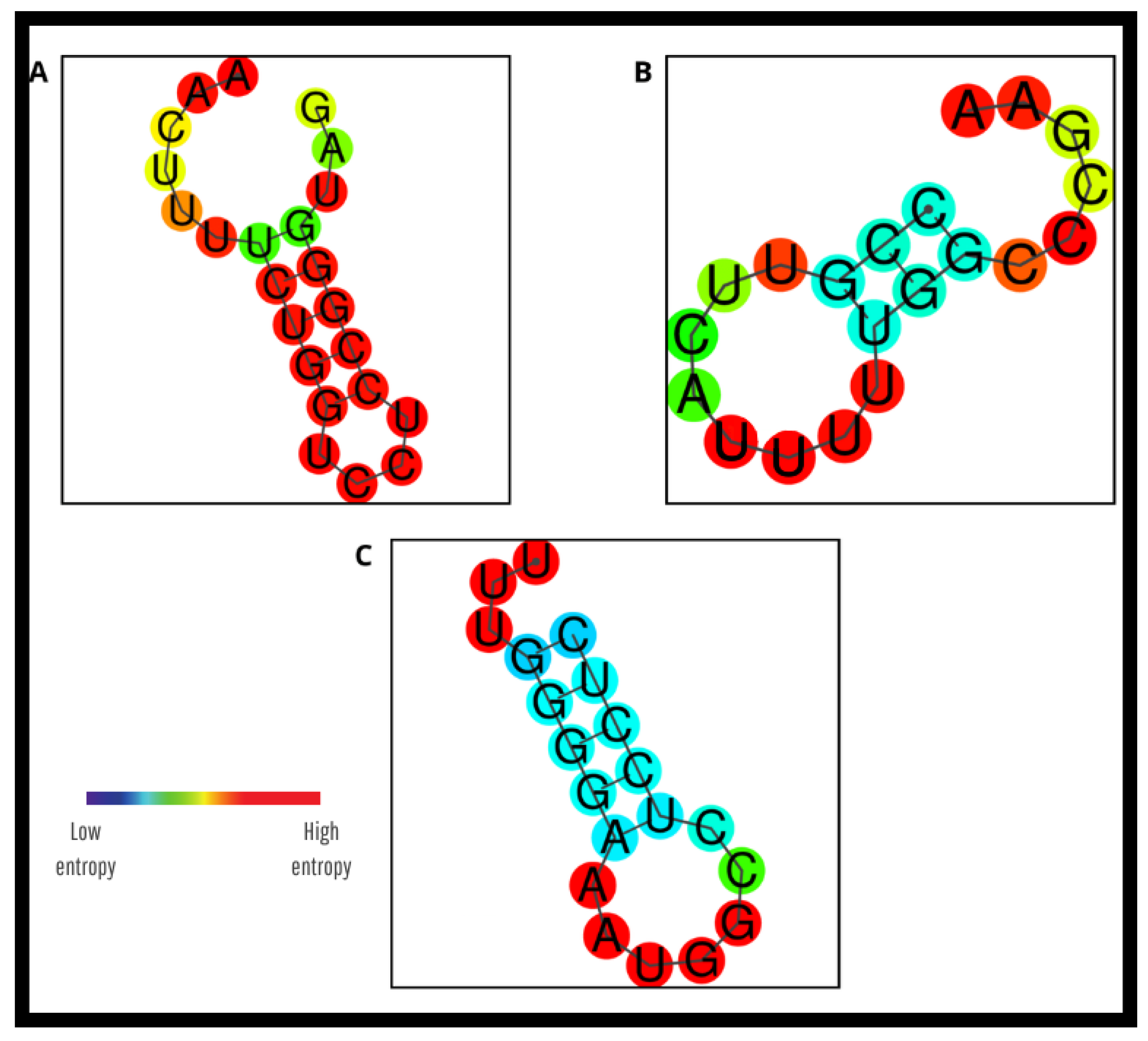

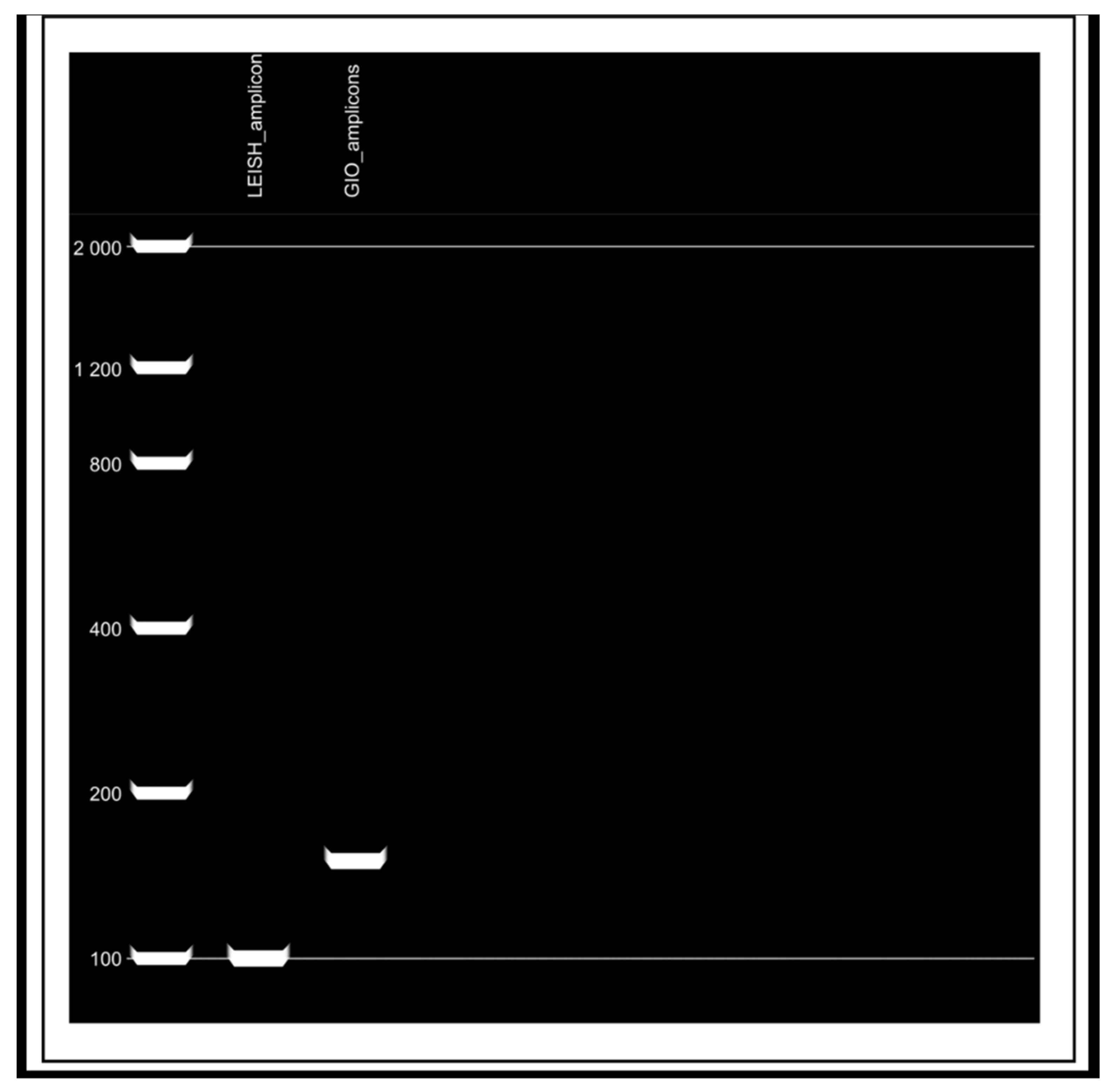

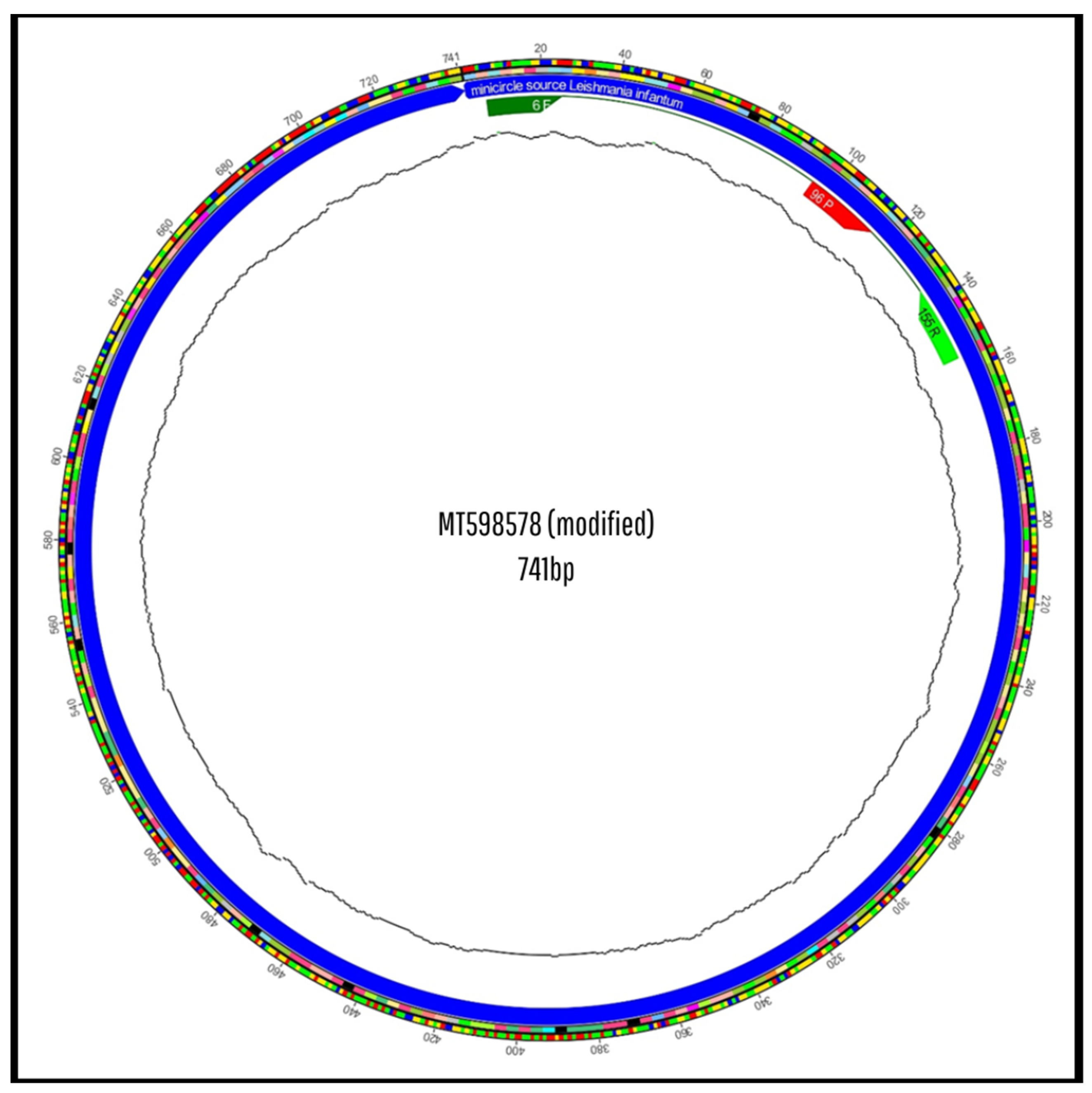

3.2. In Silico Analysis of Primer and Probe Sequences

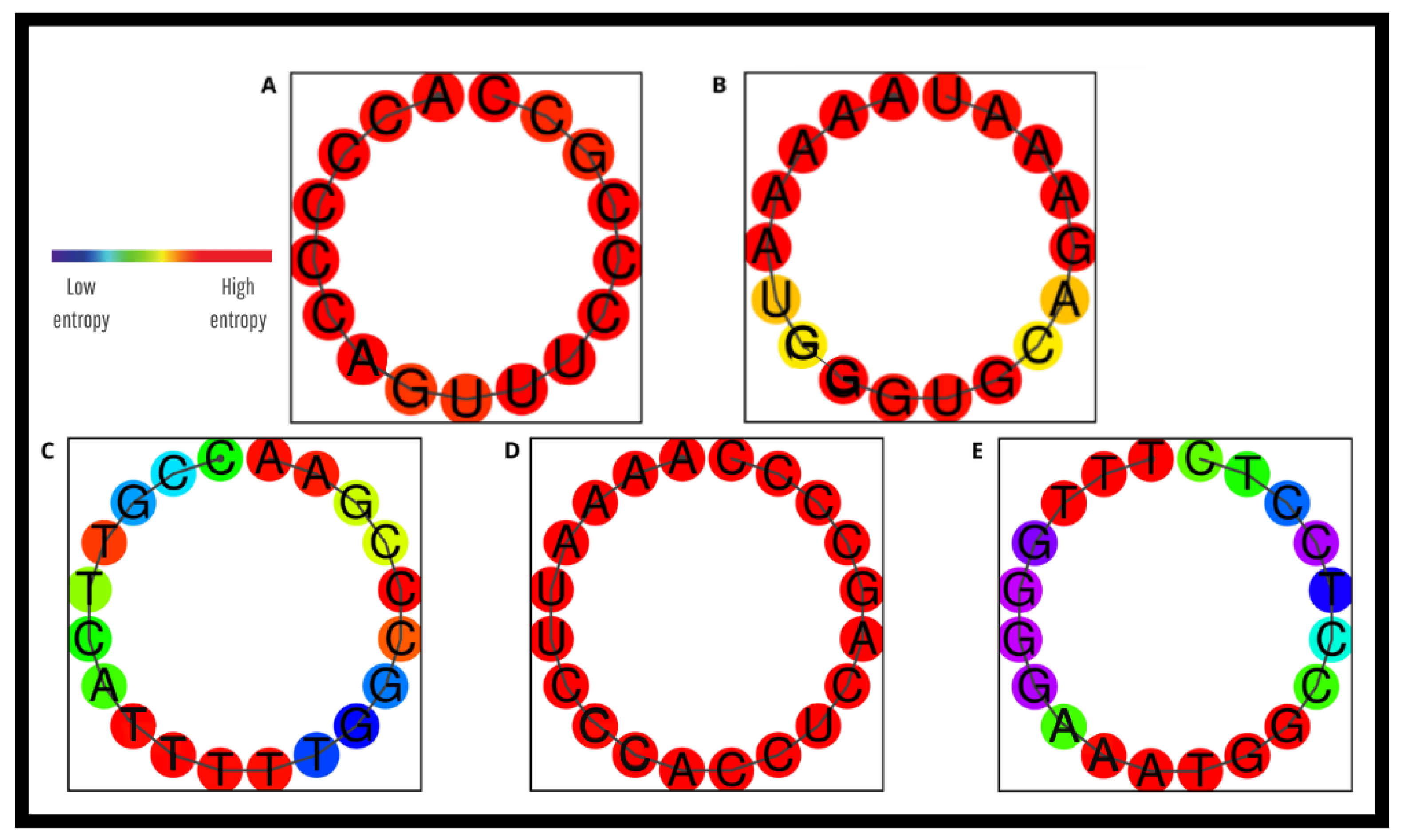

3.3. In Silico Evaluation of the New Primers and Probe

3.4. Statistical Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AVL | American Visceral Leishmaniasis |

| ELISA | Indirect Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay |

| MAFFT® | Multiple Alignment using Fast Fourier Transform |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| qPCR | Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| NTC | No Template Control |

| IFAT | Indirect Immunofluorescence Assay |

| pNPP | Chromogenic Substrate Para-Nitrophenylphosphate |

| IEC | Evandro Chagas Institute |

| NNN | Neal, Novy and Nicolle |

| Tm | Melting Temperature |

| bp | Base Pairs |

| PPV | Positive Predictive Value |

| IgG | Immunoglobulin G |

| BSA | Bovine Serum Albumin |

| PBS | Phosphate-Buffered Saline |

| PBS-T | Phosphate-Buffered Saline Tween |

| OD | Optical Density |

| nm | Nanometer |

| RPMI | Roswell Park Memorial Institute |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic acid |

| USA | United State of America |

| Cq | Cycle Quantification |

| BLAST | Basic Local Alignment Search Tool |

Appendix A

| Parameter | Primer Forward (LEISH-1) | Primer Reverse (LEISH-2) | Probe (TaqMan®-MGB Probe) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Query | LEISH-1 | LEISH-2 | Probe TaqMan® |

| Sequence ID (Subject) | MT598578.1 | MT598578.1 | MT598578.1 |

| Organism | L. donovani/infantum | L. donovani/infantum | L. donovani/infantum |

| % Identity | 100% | 100% | - |

| Query cover | 100% | 100% | - |

| Score (Bit score) | 46.1 | 34.2 | - |

| E-value | 0.023 | 88 | - |

| Alignment (Start-End) | Start-717/End-739 | Star: 63/End-47 | - |

| Expected target (Yes/No) | Yes | Yes | No |

| Name | %GC | Type | Hairpin (°C) | Sequence Size | Melting Temperature (Tm°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GIO-06F | 50.0% | Primer | 28.8 | 20 | 59.7 |

| GIO-96P | 55.0% | Probe | 33.6 | 20 | 60.0 |

| GIO-155R | 55.0% | Primer | - | 20 | 60.3 |

| Leish-1 | 52.2% | Primer | 41.1 | 23 | 67.5 |

| TaqMan®-MGB Probe | 70.6% | Probe | - | 17 | 69.9 |

| Leish-2 | 33.3% | Primer | - | 18 | 57.5 |

| Parameter | Primer Forward (GIO-06F) | Primer Reverse (GIO-155R) | TaqMan®-MGB Probe (GIO-96P) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Query | GIO-06F | GIO-155R | GIO-96P |

| Sequence ID (Subject) | MT598578.1 | MT598578.1 | MT598578.1 |

| Organism | L. donovani/infantum | L. donovani/infantum | L. donovani/ infantum |

| % Identity | 100% | 100% | 100% |

| Query cover | 100% | 100% | 100% |

| Score (Bit score) | 40.1 | 40.1 | 40.1 |

| E-value | 1.4 | 1.4 | 1.4 |

| Alignment (Start-End) | Start-06/End-25 | Start-155/End-136 | Start-96/End-115 |

| Expected target (Yes/No) | Yes | Yes | Yes |

References

- Bustin, S.A.; Benes, V.; Garson, J.A.; Hellemans, J.; Huggett, J.; Kubista, M.; Mueller, R.; Nolan, T.; Pfaffl, M.W.; Shipley, G.L.; et al. The MIQE Guidelines: Minimum Information for Publication of Quantitative Real-Time PCR Experiments. Clin. Chem. 2009, 55, 611–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.; Wakem, M.; Dijkman, G.; Alsarraj, M.; Nguyen, M. A Practical Approach to RT-qPCR—Publishing Data That Conform to the MIQE Guidelines. Methods 2010, 50, S1–S5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francino, O.; Altet, L.; Sánchez-Robert, E.; Rodriguez, A.; Solano-Gallego, L.; Alberola, J.; Ferrer, L.; Sánchez, A.; Roura, X. Advantages of Real-Time PCR Assay for Diagnosis and Monitoring of Canine Leishmaniosis. Vet. Parasitol. 2006, 137, 214–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kubista, M.; Andrade, J.M.; Bengtsson, M.; Forootan, A.; Jonák, J.; Lind, K.; Sindelka, R.; Sjöback, R.; Sjögreen, B.; Strömbom, L.; et al. The Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction. Mol. Aspects Med. 2006, 27, 95–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadle, S.; Lehnert, M.; Rubenwolf, S.; Zengerle, R.; von Stetten, F. Real-Time PCR Probe Optimization Using Design of Experiments Approach. Biomol. Detect. Quantif. 2016, 7, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Pelt-Verkuil, E.; te Witt, R. Principles of PCR. In Molecular Diagnostics: Part 1: Technical Backgrounds and Quality Aspects; van Pelt-Verkuil, E., van Leeuwen, W.B., te Witt, R., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 131–215. ISBN 9789811316043. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez, A.; Rodríguez, M.; Córdoba, J.J.; Andrade, M.J. Design of Primers and Probes for Quantitative Real-Time PCR Methods. Methods Mol. Biol. 2015, 1275, 31–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silveira, N.S.D.; Mendes, E.M.; Pereira, M.L.; Tavela, A.D.O.; Veiga, A.P.M.; Zimermann, F.C. Visceral Leishmaniasis in Dogs. Acta Sci. Vet. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PAHO. Leishmaniases: Epidemiological Report of the Americas. Available online: https://iris.paho.org/handle/10665.2/51742 (accessed on 24 July 2025).

- Saúde, M. da Casos Confirmados de Leishmaniose Visceral Americana. Available online: https://leishmanioses.aids.gov.br/app/dashboards?auth_provider_hint=anonymous1#/view/041e37d7-6f08-463e-8dd0-e43c5c2b34c4?embed=true&_g=()&show-top-menu=false (accessed on 24 July 2025).

- Maurelli, M.P.; Bosco, A.; Foglia Manzillo, V.; Vitale, F.; Giaquinto, D.; Ciuca, L.; Molinaro, G.; Cringoli, G.; Oliva, G.; Rinaldi, L.; et al. Clinical, Molecular and Serological Diagnosis of Canine Leishmaniosis: An Integrated Approach. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundar, S.; Singh, O.P. Molecular Diagnosis of Visceral Leishmaniasis. Mol. Diagn. Ther. 2018, 22, 443–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustin, S.A.; Mueller, R.; Nolan, T. Parameters for Successful PCR Primer Design. In Quantitative Real-Time PCR: Methods and Protocols; Biassoni, R., Raso, A., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 5–22. ISBN 978-1-4939-9833-3. [Google Scholar]

- Banaganapalli, B.; Shaik, N.A.; Rashidi, O.M.; Jamalalail, B.; Bahattab, R.; Bokhari, H.A.; Alqahtani, F.; Kaleemuddin, M.; Al-Aama, J.Y.; Elango, R. In Silico PCR. In Essentials of Bioinformatics, Volume I: Understanding Bioinformatics: Genes to Proteins; Shaik, N.A., Hakeem, K.R., Banaganapalli, B., Elango, R., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 355–371. ISBN 978-3-030-02634-9. [Google Scholar]

- Hendling, M.; Barišić, I. In-Silico Design of DNA Oligonucleotides: Challenges and Approaches. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2019, 17, 1056–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Jesus, R.C.S.; Lima, L.V.R.; Campos, M.B.; Ramos, P.K.S.; Laurenti, D.M.; Silveira, F.T. Reatividade de Antígenos de Amastigota e Promastigota de Leishmania (L.) Infantum chagasi No Sorodiagnóstico da Leishmaniose Visceral Canina Pela Reação de Imunofluorescência Indireta e ELISA. In Proceedings of the 52° Congresso da Sociedade Brasileira de medicina Tropical, Centro de Convenções, Maceió-Alagoas, Brazil, 21–24 August 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bradford, M.M. A Rapid and Sensitive Method for the Quantitation of Microgram Quantities of Protein Utilizing the Principle of Protein-Dye Binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976, 72, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lima, L.V.D.R.; Carneiro, L.A.; Campos, M.B.; Vasconcelos Dos Santos, T.; Ramos, P.K.; Laurenti, M.D.; Teixeira, C.E.C.; Silveira, F.T. Further Evidence Associating IgG1, but Not IgG2, with Susceptibility to Canine Visceral Leishmaniasis Caused by Leishmania (L.) Infantum chagasi-Infection. Parasite 2017, 24, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos, P.K.S.; Diniz, J.A.P.; Silva, E.O.; Quaresma, J.A.S.; Saraiva, E.M.; Seabra, S.H.; Atella, G.C.; De Souza, W. Characterization in Vivo and in Vitro of a Strain of Leishmania (Viannia) shawi from the Amazon Region. Parasitol. Int. 2009, 58, 154–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Promega, C. ReliaPrepTM gDNA Tissue Miniprep System Technical Manual for A2050, A2051 and A2052. Available online: https://www.promega.com/ (accessed on 24 July 2025).

- Fernandes, M.A.; Leonel, J.A.F.; Isaac, J.A.; Benassi, J.C.; Silva, D.T.; Spada, J.C.P.; Pereira, N.W.B.; Ferreira, H.L.; Keid, L.B.; Soares, R.M.; et al. Molecular Detection of Leishmania infantum DNA According to Clinical Stages of Leishmaniasis in Dog. Rev. Bras. Parasitol. Veterinária 2019, 28, 194–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katoh, K.; Asimenos, G.; Toh, H. Multiple Alignment of DNA Sequences with MAFFT. In Bioinformatics for DNA Sequence Analysis; Posada, D., Ed.; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, USA, 2009; pp. 39–64. ISBN 978-1-59745-251-9. [Google Scholar]

- Fotouhi-Ardakani, R.; Ghafari, S.M.; Ready, P.D.; Parvizi, P. Developing, Modifying, and Validating a TaqMan Real-Time PCR Technique for Accurate Identification of Leishmania Parasites Causing Most Leishmaniasis in Iran. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 731595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvopiña, M.; Fonseca-Carrera, D.; Villacrés-Granda, I.; Toapanta, A.; Chiluisa-Guacho, C.; Bastidas-Caldes, C. New Primers for Detection and Differentiation between Leishmania viannia and L. Leishmania Subgenera by Polymerase Chain Reaction. Iran. J. Parasitol. 2023, 18, 351–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayres, M.; Ayres, M., Jr.; Ayres, D.L.; dos Santos, A.S.; Ayres, L.L. BioEstat 5.0: Aplicações Estatísticas Nas Áreas Das Ciências Bio-Médicas; 1; Sociedade Civil Mamirauá: Belém, PA, Brazil, 2007; Volume 5. [Google Scholar]

- Bustin, S.A. Improving the Quality of Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction Experiments: 15 Years of MIQE. Mol. Aspects Med. 2024, 96, 101249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrotra, S.; Tiwari, R.; Kumar, R.; Sundar, S. Advances and Challenges in the Diagnosis of Leishmaniasis. Mol. Diagn. Ther. 2025, 29, 195–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siala, E.; Bouratbine, A.; Aoun, K. Mediterranean Visceral Leishmaniasis: Update on Biological Diagnosis. Tunis. Med. 2022, 100, 13–26. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, S.C.; Nadeau, K.; Abbasi, M.; Lachance, C.; Nguyen, M.; Fenrich, J. The Ultimate qPCR Experiment: Producing Publication Quality, Reproducible Data the First Time. Trends Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 761–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klymus, K.E.; Ruiz Ramos, D.V.; Thompson, N.L.; Richter, C.A. Development and Testing of Species-Specific Quantitative PCR Assays for Environmental DNA Applications. J. Vis. Exp. 2020, 165, e61825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Pelt-Verkuil, E.; te Witt, R. Primers and Probes. In Molecular Diagnostics: Part 1: Technical Backgrounds and Quality Aspects; van Pelt-Verkuil, E., van Leeuwen, W.B., te Witt, R., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 51–95. ISBN 9789811316043. [Google Scholar]

- Çerçi, S.; Cecchinato, M.E.; Vines, J. How Design Researchers Interpret Probes: Understanding the Critical Intentions of a Designerly Approach to Research. In Proceedings of the 2021 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Virtual, 8–13 May 2021; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Bustin, S.A.; Ruijter, J.M.; van den Hoff, M.J.B.; Kubista, M.; Pfaffl, M.W.; Shipley, G.L.; Tran, N.; Rödiger, S.; Untergasser, A.; Mueller, R.; et al. MIQE 2.0: Revision of the Minimum Information for Publication of Quantitative Real-Time PCR Experiments Guidelines. Clin. Chem. 2025, 71, 634–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grätz, C.; Bui, M.L.U.; Thaqi, G.; Kirchner, B.; Loewe, R.P.; Pfaffl, M.W. Obtaining Reliable RT-qPCR Results in Molecular Diagnostics—MIQE Goals and Pitfalls for Transcriptional Biomarker Discovery. Life 2022, 12, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samal, K.C.; Sahoo, J.P.; Behera, L.; Dash, T. Understanding the BLAST (Basic Local Alignment Search Tool) Program and a Step-by-Step Guide for Its Use in Life Science Research. Bhartiya Krishi Anusandhan Patrika 2021, 36, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratzlaff, F.R.; Osmari, V.; da Silva, D.; de Paula Vasconcellos, J.S.; Pötter, L.; Fernandes, F.D.; de Mello Filho, J.A.; de Avila Botton, S.; Vogel, F.S.F.; Sangioni, L.A. Identification of Infection by Leishmania spp. in Wild and Domestic Animals in Brazil: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis (2001–2021). Parasitol. Res. 2023, 122, 1605–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Samples | Samples (N) | Region/IFAT * | Positive (%) | Negative (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Domestic Dogs | 60 | Endemic (IFAT * IgG ** +) | 30/30 (100%) | 0/30 (0%) |

| Non-Endemic (IFAT * IgG ** −) | 0/30 (0%) | 30/30 (100%) | ||

| Wild Animals | 25 | Endemic | 9/25 (36%) | 16/25 (64%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Haber, G.Z.; da Costa, L.D.; Costa, E.B.M.; Araújo, R.F.; de Souza, T.N.; Queiroz, L.d.R.L.; Diniz, B.T.N.; Sousa Junior, E.C.; Martis, L.C.; Ramos, P.K.S.; et al. Specificity of Primers and Probes for Molecular Diagnosis of Leishmania (Leishmania) chagasi in Dogs and Wild Animals. Pathogens 2025, 14, 1065. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14101065

Haber GZ, da Costa LD, Costa EBM, Araújo RF, de Souza TN, Queiroz LdRL, Diniz BTN, Sousa Junior EC, Martis LC, Ramos PKS, et al. Specificity of Primers and Probes for Molecular Diagnosis of Leishmania (Leishmania) chagasi in Dogs and Wild Animals. Pathogens. 2025; 14(10):1065. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14101065

Chicago/Turabian StyleHaber, Giovanna Zandonadi, Leila Dias da Costa, Erick Bruno Monteiro Costa, Railton Farias Araújo, Tainá Negreiros de Souza, Luciana do Rêgo Lima Queiroz, Bruno Tardelli Nunes Diniz, Edivaldo Costa Sousa Junior, Lívia Carício Martis, Patrícia Karla Santos Ramos, and et al. 2025. "Specificity of Primers and Probes for Molecular Diagnosis of Leishmania (Leishmania) chagasi in Dogs and Wild Animals" Pathogens 14, no. 10: 1065. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14101065

APA StyleHaber, G. Z., da Costa, L. D., Costa, E. B. M., Araújo, R. F., de Souza, T. N., Queiroz, L. d. R. L., Diniz, B. T. N., Sousa Junior, E. C., Martis, L. C., Ramos, P. K. S., & Silveira, F. T. (2025). Specificity of Primers and Probes for Molecular Diagnosis of Leishmania (Leishmania) chagasi in Dogs and Wild Animals. Pathogens, 14(10), 1065. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14101065