Management of Odontogenic Infections in Pregnant Patients: Case-Based Approach and Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

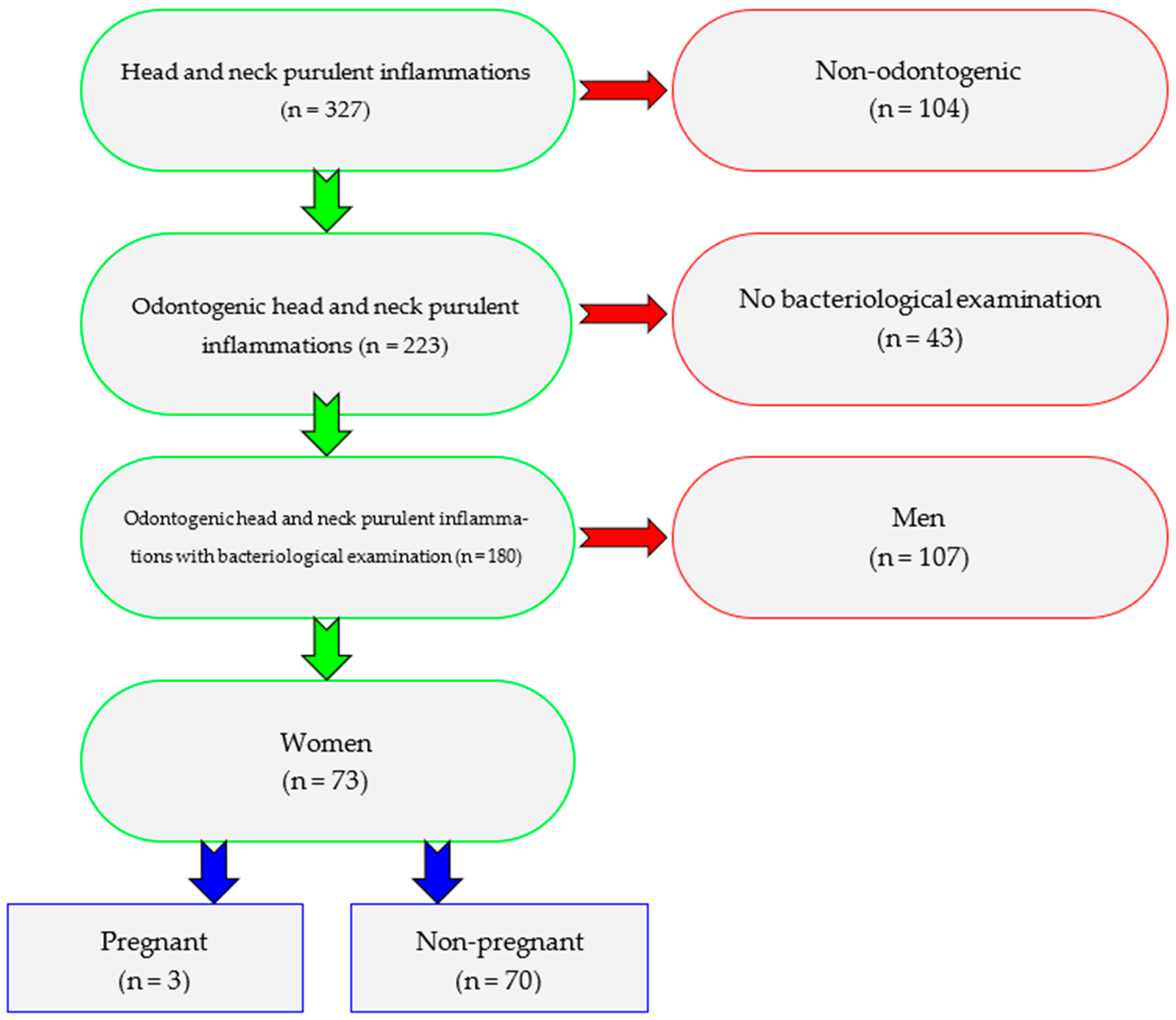

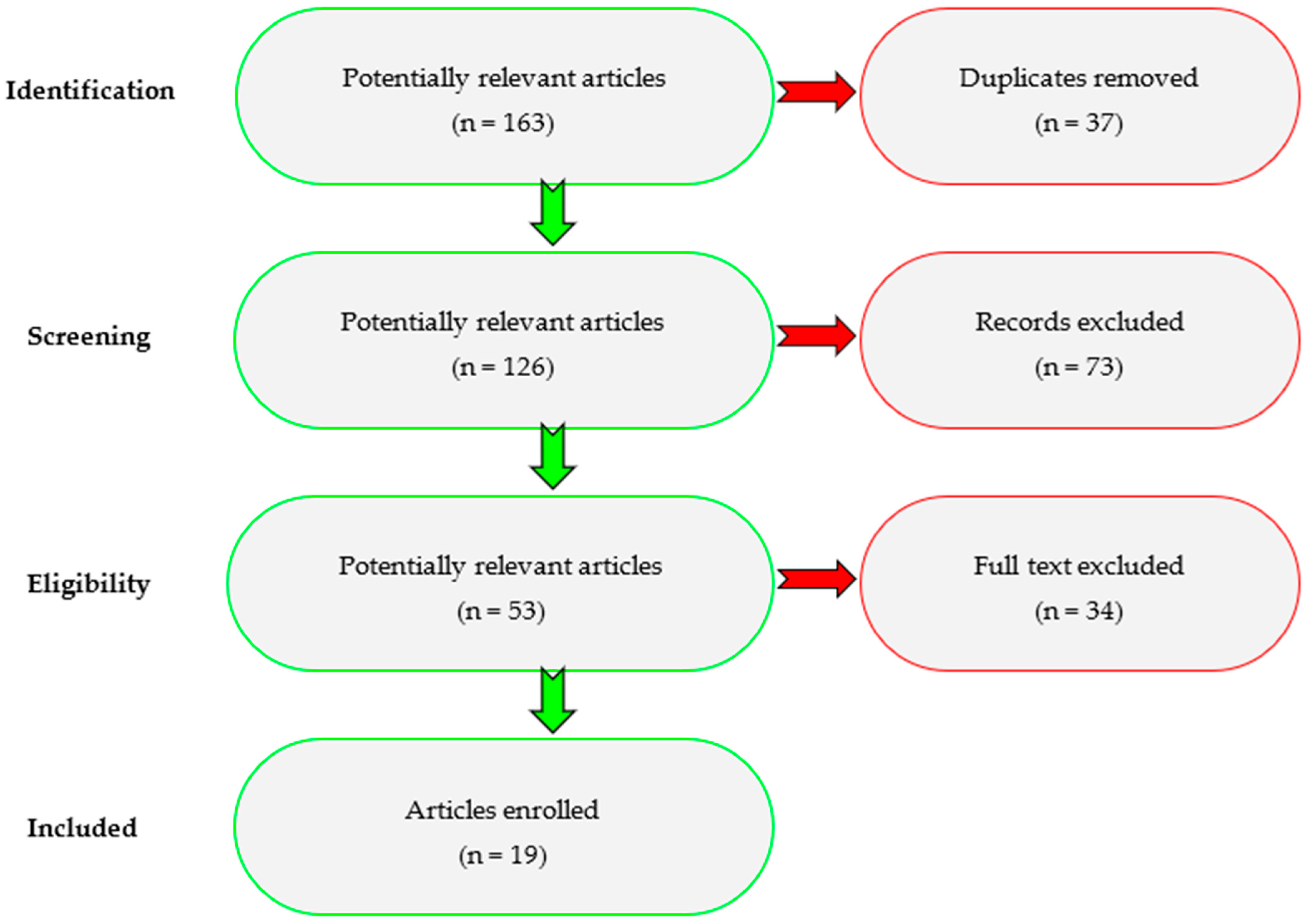

2. Materials and Methods

- Existence of odontogenic abscess.

- Presence of bacteriological examination.

- Female sex.

- Pregnancy.

- -

- Duplicates.

- -

- Non-odontogenic head and neck infections, studies unrelated to pregnancy.

- -

- No full text, reviews, editorials, unclear results.

3. Results

3.1. Cases Presentations

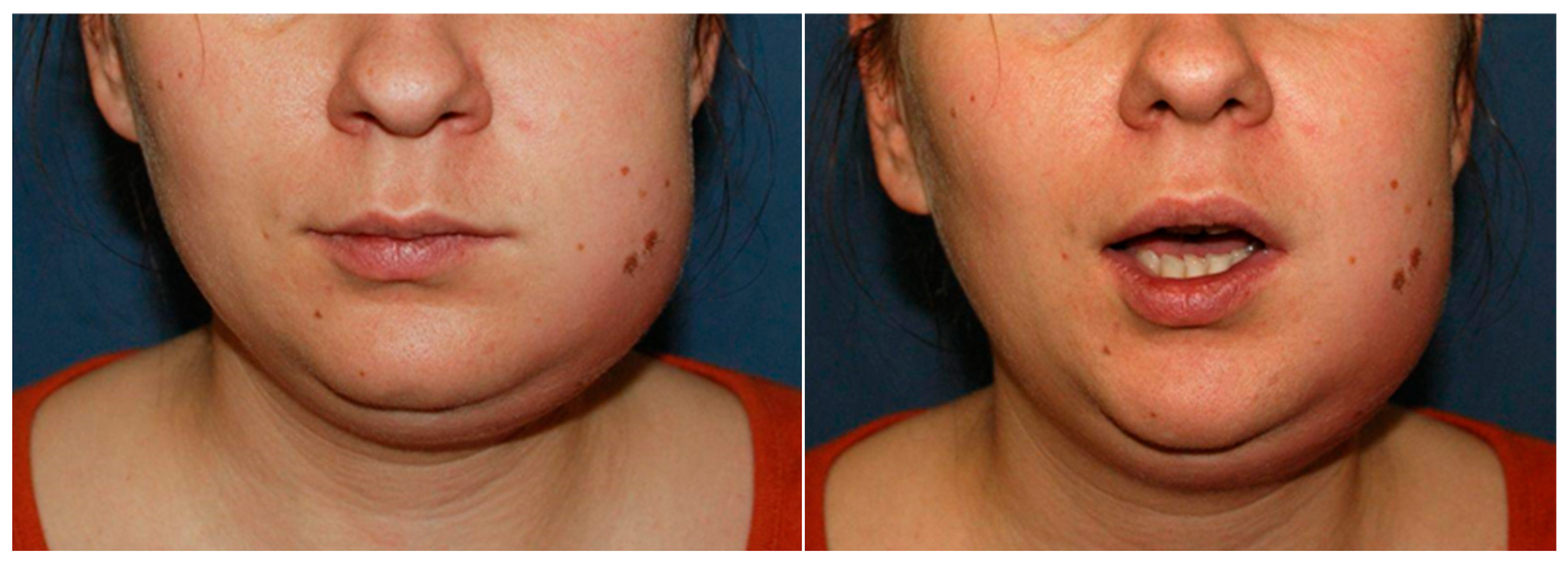

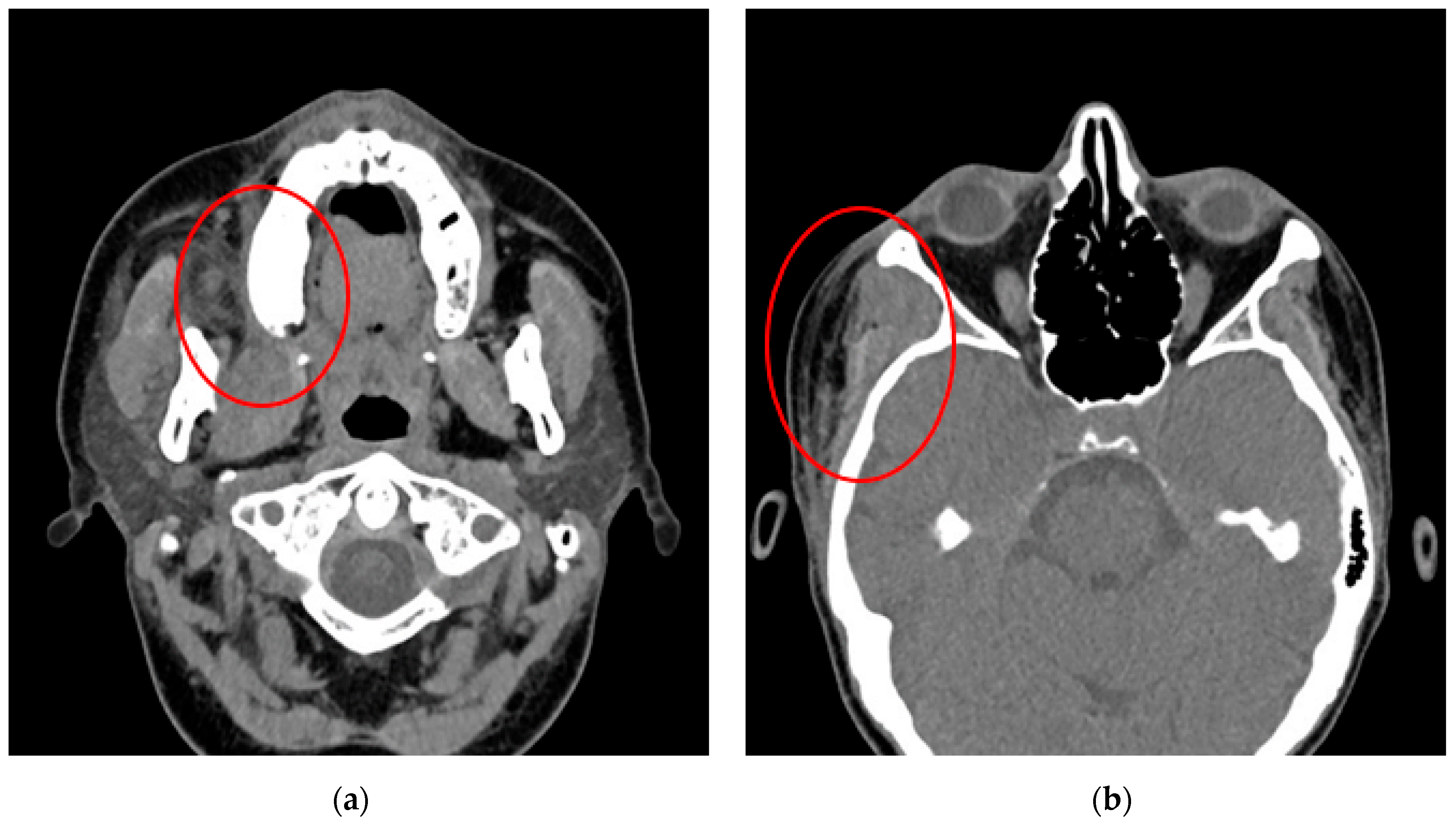

3.1.1. Case No. 1

3.1.2. Case No. 2

3.1.3. Case No. 3

3.2. Pregnant vs. Non-Pregnant Women

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SIRS | Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome |

| G-P-A-L | Gravida–Para–Abortions–Living children |

| TA-USG | Transabdominal–Ultrasonography |

| TV-USG | Transvaginal–Ultrasonography |

| ICU | Intensive Care Unit |

| LA | Ludwig’s angina |

| ARDS | Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome |

References

- Mahran, H.; Al Ashwah, A.; Rizq, M. Severe Deep Fascial Spaces Infections with Pregnancy: A Retrospective Study. Surg. Infect. 2024, 25, 762–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, M.K.; McCutcheon, C.R.; Petroff, M.G. Impact of Estrogen and Progesterone on Immune Cells and Host-Pathogen Interactions in the Lower Female Reproductive Tract. J. Immunol. 2022, 209, 1437–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieske, B.; Makarova, N.; Jagemann, B.; Walther, C.; Ebinghaus, M.; Zyriax, B.-C.; Aarabi, G. Inflammatory Response in Oral Biofilm during Pregnancy: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pecci-Lloret, M.P.; Linares-Pérez, C.; Pecci-Lloret, M.R.; Rodríguez-Lozano, F.J.; Oñate-Sánchez, R.E. Oral Manifestations in Pregnant Women: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neal, T.W.; Schlieve, T. Complications of Severe Odontogenic Infections: A Review. Biology 2022, 11, 1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pucci, R.; Cassoni, A.; Di Carlo, D.; Della Monaca, M.; Romeo, U.; Valentini, V. Severe Odontogenic Infections during Pregnancy and Related Adverse Outcomes. Case Report and Systematic Literature Review. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2021, 6, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navya; Chacko, L.K.; Shenoy, R.P.; Kalladka, P.K. Oral health status and quality of life among pregnant women with oral health problems: A descriptive study. BMC Oral Health 2025, 25, 1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silk, H.; Douglass, A.B.; Douglass, J.M.; Silk, L. Oral health during pregnancy. Am. Fam. Physician 2008, 77, 1139–1144. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- George, A.; Shamim, S.; Johnson, M.; Ajwani, S.; Bhole, S.; Blinkhorn, A.; Ellis, S.; Andrews, K. Periodontal treatment during pregnancy and birth outcomes: A meta-analysis of randomised trials. Int. J. Evid.-Based Healthc. 2011, 9, 122–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarannum, F.; Faizuddin, M. Effect of periodontal therapy on pregnancy outcome in women affected by periodontitis. J. Periodontol. 2007, 78, 2095–2103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, X.; Buekens, P.; Fraser, W.D.; Beck, J.; Offenbacher, S. Periodontal disease and adverse pregnancy outcomes: A systematic review. BJOG 2006, 113, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliabadi, T.; Saberi, E.A.; Motameni Tabatabaei, A.; Tahmasebi, E. Antibiotic use in endodontic treatment during pregnancy: A narrative review. Eur. J. Transl. Myol. 2022, 32, 10813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Q.; Cai, Y.; Wang, X.; Liu, G.; Luan, Q. Nomogram prediction for periodontitis in Chinese pregnant women with different sociodemographic and oral health behavior characteristics: A community-based study. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Rashwan, N.; Al Jallad, N.; Wu, Y.; Lu, X.; Wu, T.; Xiao, J. Maternal and infant oral health benefits from mothers receiving prenatal total oral rehabilitation: A pilot prospective birth cohort study. Front. Oral Health 2024, 5, 1443337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, M.A.; Crall, J.; Goldenberg, R.L.; Schulkin, J. Oral health during pregnancy. J. Matern.-Fetal Neonatal Med. 2009, 22, 733–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartnett, E.; Haber, J.; Krainovich-Miller, B.; Bella, A.; Vasilyeva, A.; Kessler, J.L. Oral Health in Pregnancy. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 2016, 45, 565–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łysenko, L.; Leśnik, P.; Nelke, K.; Gerber, H. Immune disorders in sepsis and their treatment as a significant problem of modern intensive care. Postęp. Hig. Med. Dośw. 2017, 71, 703–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moorhead, K.; Guiahi, M. Pregnancy complicated by Ludwig’s angina requiring delivery. Infect. Dis. Obs. Gynecol. 2010, 2010, 158264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaji, V.C.R.; Vani, K. Ludwig’s Angina During Pregnancy—A Case Report. Indian J. Dent. Res. 2024, 35, 104–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trahan, M.J.; Nicholls-Dempsey, L.; Richardson, K.; Wou, K. Ludwig’s Angina in Pregnancy: A Case Report. J. Obs. Gynaecol. Can. 2020, 42, 1267–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, E.A.M.; Eltayeb, A.S.; Osman, M.A.K. Delay in the Referral of Pregnant Patients with Fascial Spaces Infection: A Cross-Sectional Observational Study from Khartoum Teaching Dental Hospital, Sudan. J. Maxillofac. Oral Surg. 2020, 19, 298–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamim, F.; Bahadur, A.; Ghandhi, D.; Aijaz, A. Management of difficult airway in a pregnant patient with severely reduced mouth opening. J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 2021, 71, 1011–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, T.; Ahmed, S.; Rahman, S. Decompression of Ludwig’s angina in a pregnant patient under bilateral superficial cervical plexus block. J. Perioper. Pract. 2022, 32, 66–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalla Torre, D.; Burtscher, D.; Höfer, D.; Kloss, F.R. Odontogenic deep neck space infection as life-threatening condition in pregnancy. Aust. Dent. J. 2014, 59, 375–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, R.; Bhate, K.; Manoj Kumar, U.; Londhe, U.; Bawane, S.; Chincholkar, A. Maternal and Foetal care in odontogenic infections: A well curated management. Int. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2024, 123, 110131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gil-Montoya, J.A.; Rivero-Blanco, T.; Leon-Rios, X.; Exposito-Ruiz, M.; Pérez-Castillo, I.; Aguilar-Cordero, M.J. Oral and general health conditions involved in periodontal status during pregnancy: A prospective cohort study. Arch. Gynecol. Obs. 2023, 308, 1765–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukherjee, S.; Sharma, S.; Maru, L. Poor dental hygiene in pregnancy leading to submandibular cellulitis and intrauterine fetal demise: Case report and literature review. Int. J. Prev. Med. 2013, 4, 603–606. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hobson, D.T.G.; Imudia, A.N.; Soto, E.; Awonuga, A.O. Pregnancy complicated by recurrent brain abscess after extraction of an infected tooth. Obs. Gynecol. 2011, 118 Pt 2, 467–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, D.; Cheng, A.; Kunchur, R.; Lam, S.; Sambrook, P.J.; Goss, A.N. Management of severe odontogenic infections in pregnancy. Aust. Dent. J. 2012, 57, 498–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çelebi, N.; Kütük, M.S.; Taş, M.; Soylu, E.; Etöz, O.A.; Alkan, A. Acute fetal distress following tooth extraction and abscess drainage in a pregnant patient with maxillofacial infection. Aust. Dent. J. 2013, 58, 117–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wazir, S.; Khan, M.; Mansoor, N.; Wazir, A. Odontogenic fascial space infections in pregnancy: A study. Pak. Oral Dent. J. 2013, 33, 17–22. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, R.D.S.; Gomes-Ferreira, P.H.S.; Bonardi, J.P.; Silva, J.R.D.; Latini, G.L.; Hochuli-Vieira, E. Dental Infection and Pregnancy: The Lack of Treatment by the Dental Professional Evolving to a Complex Maxillofacial Infection. J. Craniofacial Surg. 2017, 28, e748–e750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Figueiredo, M.G.O.P.; Takita, S.Y.; Dourado, B.M.R.; Mendes, H.S.; Terakado, E.O.; Nunes, H.R.C.; Fonseca, C.R.B.D. Periodontal disease: Repercussions in pregnant woman and newborn health—A cohort study. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0225036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamath, A.T.; Bhagania, M.K.; Balakrishna, R.; Sevagur, G.K.; Amar, R. Ludwig’s Angina in Pregnancy Necessitating Pre Mature Delivery. J. Maxillofac. Oral. Surg. 2015, 14 (Suppl. 1), 186–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aziz, Z.; Aboulouidad, S.; Bouihi, M.E.; Fawzi, S.; Lakouichmi, M.; Hattab, N.M. Odontogenic cervico-facial cellulitis during pregnancy: About 3 cases. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2020, 36, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tocaciu, S.; Robinson, B.W.; Sambrook, P.J. Severe odontogenic infection in pregnancy: A timely reminder. Aust. Dent. J. 2017, 62, 98–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Pregnant Women (N = 3) | Non-Pregnant Women (N = 70) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age [years] | Mean (SD) | 31.33 (3.06) | 42.6 (18.27) | p = 0.293 |

| Median (quartiles) | 32 (30–33) | 39 (27–55.75) | ||

| Range | 28–34 | 18–86 | ||

| n | 3 | 70 | ||

| VAS | <5 | 1 (33.33%) | 13 (18.57%) | p = 1 |

| ≥5 | 2 (66.67%) | 33 (47.14%) | ||

| Unknown | 0 (0.00%) | 24 (34.29%) | ||

| Infected spaces | 1 | 1 (33.33%) | 60 (85.71%) | p = 0.068 |

| ≥2 | 2 (66.67%) | 10 (14.29%) | ||

| Bacteriological test | Positive | 2 (66.67%) | 55 (78.57%) | p = 0.53 |

| Negative | 1 (33.33%) | 15 (21.43%) | ||

| Anaerobic bacteria | Present | 2 (66.67%) | 28 (40.00%) | p = 0.564 |

| Absent | 1 (33.33%) | 42 (60.00%) | ||

| Aerobic bacteria | Present | 2 (66.67%) | 39 (55.71%) | p = 1 |

| Absent | 1 (33.33%) | 31 (44.29%) | ||

| Bacterial species | 0–1 | 1 (33.33%) | 38 (54.29%) | p = 0.595 |

| ≥2 | 2 (66.67%) | 32 (45.71%) | ||

| Number of teeth extracted | 0–1 | 1 (33.33%) | 54 (77.14%) | p = 0.148 |

| ≥2 | 2 (66.67%) | 16 (22.86%) | ||

| Empirical antibiotic therapy | Yes | 3 (100.00%) | 69 (98.57%) | p = 1 |

| No | 0 (0.00%) | 1 (1.43%) | ||

| Targeted antibiotic therapy | Yes | 2 (66.67%) | 15 (21.43%) | p = 0.133 |

| No | 1 (33.33%) | 55 (78.57%) | ||

| Hospitalization time | <4 days | 1 (33.33%) | 44 (62.86%) | p = 0.554 |

| ≥4 days | 2 (66.67%) | 26 (37.14%) | ||

| Intubation | Yes | 1 (33.33%) | 4 (5.71%) | p = 0.194 |

| No | 2 (66.67%) | 66 (94.29%) | ||

| First Author/Year of Publication | No. of Cases | Age (Average) | Gestation Trimester | Type of Abscess | Bacteriological Examination | Hospitalization—Days (Average) | ICU Stay—Days | Complications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moorhead/2010 [18] | 1 | 24 | 3rd | LA | polymicrobial | 9 | 8 | ARDS, C-section |

| Hobson/2011 [28] | 1 | 35 | 2nd | pterygomandibular | polymicrobial | 14 | 14 | subdural empyema, recurrent brain abscesses (frontal, temporal, and parietal lobe); Broca’s aphasia and apraxia with right hemiplegia |

| Wong/2012 [29] | 5 | 22–33 (28.4) | 1st (n = 2), 3rd (n = 3) | submandibular (n = 3), buccal (n = 1), sub masseteric and buccal (n = 1) | no data | 1–6 (3) | 1 (n = 1), 3 (n = 1) | C-section (n = 1) |

| Kamath/2012 [34] | 1 | 24 | 3rd | LA | polymicrobial | 21 | no | C-section, reoperation |

| Celebi/2013 [30] | 1 | 28 | 3rd | perimandibular and masticator space | no data | refused to be admitted | no | C-section |

| Wazir/2013 [31] | 28 | 17–30 (24.8) | 1st (n = 6), 2nd (n = 8), 3rd (n = 14) | LA (n = 10), submandibular (n = 8), submandibular and submental (n = 4), buccal (n = 2), masseteric (n = 2), submental (n = 1), maxillary canine (n = 1) | no data | no data | no data | no |

| Mukherjee/2013 [27] | 1 | 38 | 3rd | phlegmon | no data | no data | no data | intrauterine fetal demise |

| Dalla Torre/2013 [24] | 1 | 25 | 3rd | submandibular | polymicrobial | around 7 weeks | around 3 weeks | maternal ARDS and sepsis, intrauterine fetal demise, abscesses at the skull base, around the trachea and esophagus, mediastinitis and pleural empyema |

| Tocaciu/2017 [36] | 1 | 29 | 2nd | phlegmon | no data | no data | 3 | no |

| Pereira/2017 [32] | 1 | 30 | 3rd | buccal and submasseteric | monomicrobial | around 6 weeks | no | no |

| Ali/2019 [21] | 10 | 18–35 (26.5) | 2nd (n = 4), 3rd (n = 6) | submandibular (n = 7), LA (n = 2), submental (n = 1) | no data | 1–22 (6.3) | no | necrotizing fasciitis (n = 2), delivery (n = 1) |

| Trahan/2020 [20] | 1 | 34 | 3rd | LA | polymicrobial | 9 | 5 | C-section |

| Aziz/2020 [35] | 3 | 31, 24, 28, (27.7) | 3rd (n = 3) | submandibular (n = 2), submental (n = 1) | monomicrobial | 13, 17, 8 (12.7) | no | preterm delivery (n = 1) |

| Shamim/2021 [22] | 1 | 40 | 2nd | LA | no data | no data | no | intraoperatively failed intubation |

| Pucci/2021 [6] | 1 | 36 | 3rd | submandibular | no data | around 2 weeks | no | C-section |

| Rahman/2022 [23] | 1 | 25 | 3rd | LA | no data | 4 | no | no |

| Balaji/2024 [19] | 1 | 26 | 3rd | LA | monomicrobial | 12 | 6 | C-section |

| Jain/2024 [25] | 1 | 28 | 2nd | phlegmon | negative | 5 | no | no |

| Present study | 3 | 28, 32, 34 (31) | 2nd (n = 2), 3rd (n = 1) | phlegmon (n = 1), perimandibular (n = 1), LA (n = 1) | monomicrobial (n = 1), polymicrobial (n = 1) | 2, 11, 15 (9.3) | 2 (n = 1), no (n = 2) | C-section (n = 1), reoperation (n = 2) |

| Total | 63 | 18–40 (29.5) | 1st (n = 8), 2nd (n = 18), 3rd (n = 37) | one space (n = 33), two spaces (n = 7), LA (n = 19), phlegmon (n = 4) | monomicrobial (n = 6), polymicrobial (n = 6), negative (n = 1), no data (n = 50) | 1–49 (average 15; n = 31), no (n = 1), no data (n = 31) | 1–21 (average 7; n = 9), no (n = 25), no data (n = 29) | C-section/delivery (n = 10), intrauterine fetal demise (n = 2) reoperations, ARDS or sepsis, brain abscesses or empyema, necrotizing fasciitis, no (n = 32) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hramyka, A.; Wieczorkiewicz, A.; Bargiel, J.; Śliwiński, K.; Gąsiorowski, K.; Marecik, T.; Szczurowski, P.; Wyszyńska-Pawelec, G.; Zapała, J.; Gontarz, M. Management of Odontogenic Infections in Pregnant Patients: Case-Based Approach and Literature Review. Pathogens 2025, 14, 1024. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14101024

Hramyka A, Wieczorkiewicz A, Bargiel J, Śliwiński K, Gąsiorowski K, Marecik T, Szczurowski P, Wyszyńska-Pawelec G, Zapała J, Gontarz M. Management of Odontogenic Infections in Pregnant Patients: Case-Based Approach and Literature Review. Pathogens. 2025; 14(10):1024. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14101024

Chicago/Turabian StyleHramyka, Andrei, Agata Wieczorkiewicz, Jakub Bargiel, Krzysztof Śliwiński, Krzysztof Gąsiorowski, Tomasz Marecik, Paweł Szczurowski, Grażyna Wyszyńska-Pawelec, Jan Zapała, and Michał Gontarz. 2025. "Management of Odontogenic Infections in Pregnant Patients: Case-Based Approach and Literature Review" Pathogens 14, no. 10: 1024. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14101024

APA StyleHramyka, A., Wieczorkiewicz, A., Bargiel, J., Śliwiński, K., Gąsiorowski, K., Marecik, T., Szczurowski, P., Wyszyńska-Pawelec, G., Zapała, J., & Gontarz, M. (2025). Management of Odontogenic Infections in Pregnant Patients: Case-Based Approach and Literature Review. Pathogens, 14(10), 1024. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14101024