Anti-Toxoplasma gondii Antibodies in European Residents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Studies Published between 2000 and 2020

Abstract

:1. Introduction

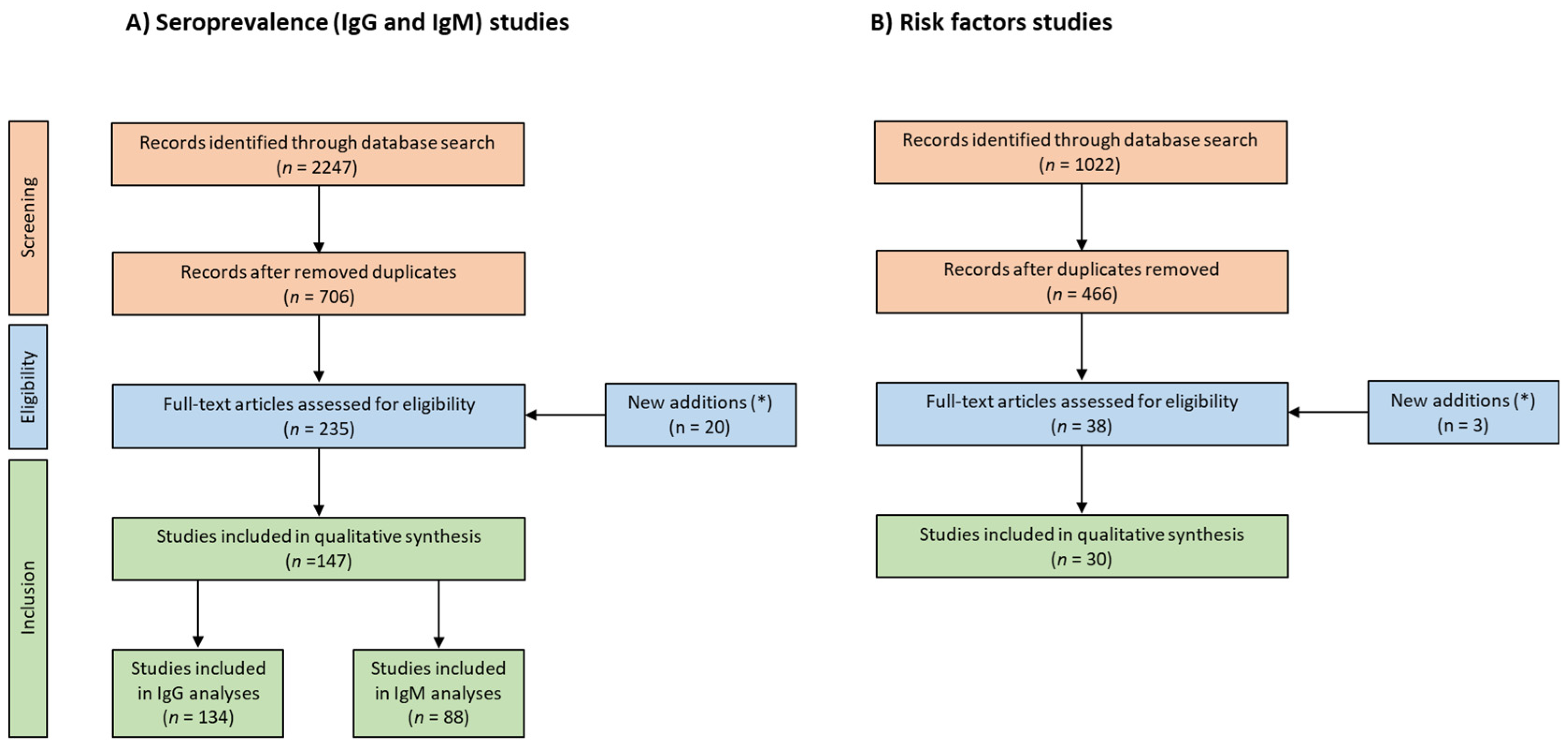

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

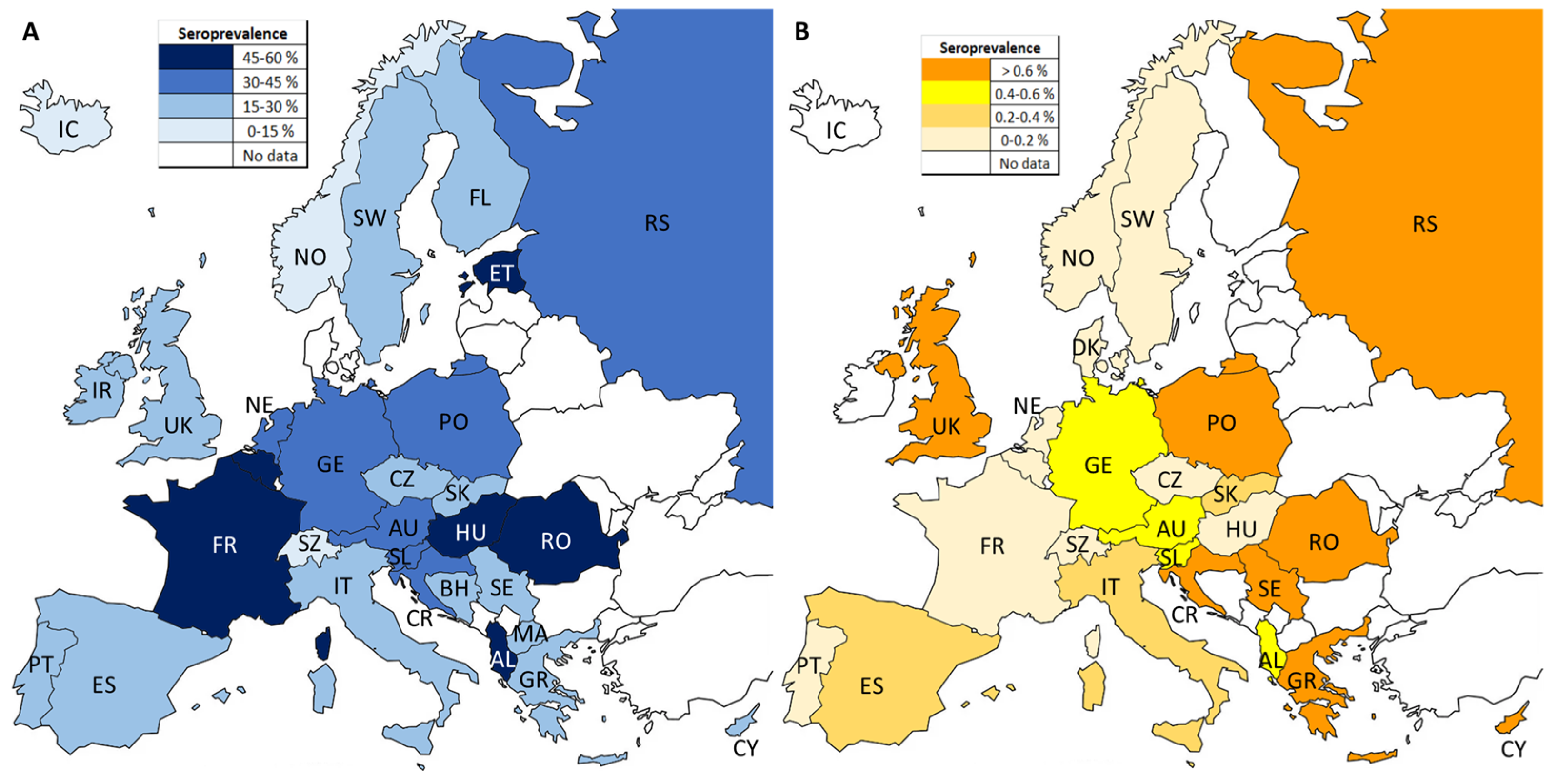

3.1. Seroprevalence of Anti-T. gondii IgG in European Residents

3.2. Seroprevalence of Anti-T. gondii IgM in European Residents

3.3. Identification of Risk Factors

4. Discussion

- (a)

- There is a lack of seroprevalence data from several countries (e.g., Baltic states).

- (b)

- Apparent regional differences may be due to the absence of harmonized data (e.g., type of target population), but also due to differences in a country’s culinary customs and sociodemographic development index.

- (c)

- The high heterogeneity observed indicates the lack of harmonization of approaches (e.g., diagnostic methods) for T. gondii seroprevalence investigations in Europe. Given the high heterogeneity observed in the present study, it is clear that surveillance systems should first be implemented, and then harmonized in European countries [6,7,176].

- (d)

- Development of up-to-date risk assessment (local/regional) studies taking into consideration particular trends are needed.

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dubey, J.P. Toxoplasmosis of Animals and Humans, 3rd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2022; pp. 1–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flegr, J.; Prandota, J.; Sovičková, M.; Israili, Z.H. Toxoplasmosis—A Global Threat. Correlation of Latent Toxoplasmosis with Specific Disease Burden in a Set of 88 Countries. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e90203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stelzer, S.; Basso, W.; Benavides Silván, J.; Ortega-Mora, L.M.; Maksimov, P.; Gethmann, J.; Conraths, F.J.; Schares, G. Toxoplasma gondii Infection and Toxoplasmosis in Farm Animals: Risk Factors and Economic Impact. Food Waterborne Parasitol. 2019, 15, e00037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dámek, F.; Swart, A.; Waap, H.; Jokelainen, P.; Le Roux, D.; Deksne, G.; Deng, H.; Schares, G.; Lundén, A.; Álvarez-García, G.; et al. Systematic Review and Modelling of Age-Dependent Prevalence of Toxoplasma gondii in Livestock, Wildlife and Felids in Europe. Pathogens 2023, 12, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bobić, B.; Nikolić, A.; Klun, I.; Djurković-Djaković, O. Kinetics of Toxoplasma Infection in the Balkans. Wien. Klin. Wochenschr. 2011, 123, 2–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peyron, F.; Mc Leod, R.; Ajzenberg, D.; Contopoulos-Ioannidis, D.; Kieffer, F.; Mandelbrot, L.; Sibley, L.D.; Pelloux, H.; Villena, I.; Wallon, M.; et al. Congenital Toxoplasmosis in France and the United States: One Parasite, Two Diverging Approaches. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2017, 11, e0005222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobić, B.; Villena, I.; Stillwaggon, E. Prevention and Mitigation of Congenital Toxoplasmosis. Economic Costs and Benefits in Diverse Settings. Food Waterborne Parasitol. 2019, 16, e00058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- SYROCOT (Systematic Review on Congenital Toxoplasmosis) study group; Thiébaut, R.; Leproust, S.; Chêne, G.; Gilbert, R. Effectiveness of Prenatal Treatment for Congenital Toxoplasmosis: A Meta-Analysis of Individual Patients’ Data. Lancet 2007, 369, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassini, A.; Colzani, E.; Pini, A.; Mangen, M.J.; Plass, D.; McDonald, S.A.; Maringhini, G.; van Lier, A.; Haagsma, J.A.; Havelaar, A.H.; et al. Impact of Infectious Diseases on Population Health Using Incidence-Based Disability-Adjusted Life Years (DALYs): Results from the Burden of Communicable Diseases in Europe study, European Union and European Economic Area Countries, 2009 to 2013. Euro Surveill. 2018, 23, 17–00454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA (European Food Safety Authority); ECDC (European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control). The European Union Summary Report on Trends and Sources of Zoonoses, Zoonotic Agents and Food-Borne Outbreaks in 2017. EFSA J. 2018, 16, e05500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, A.J.; Gilbert, R.E.; Buffolano, W.; Zufferey, J.; Petersen, E.; Jenum, P.A.; Foulon, W.; Semprini, A.E.; Dunn, D.T. On Behalf of the European Research Network on Congenital Toxoplasmosis. Sources of Toxoplasma Infection in Pregnant Women: European Multicentre Case-Control Study. BMJ 2000, 321, 142–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belluco, S.; Simonato, G.; Mancin, M.; Pietrobelli, M.; Ricci, A. Toxoplasma gondii Infection and Food Consumption: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Case-Controlled Studies. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2018, 58, 3085–3096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friesema, I.H.M.; Hofhuis, A.; Hoek-van Deursen, D.; Jansz, A.R.; Ott, A.; van Hellemond, J.J.; van der Giessen, J.; Kortbeek, L.M.; Opsteegh, M. Risk Factors for Acute Toxoplasmosis in the Netherlands. Epidemiol. Infect. 2023, 151, e95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thebault, A.; Kooh, P.; Cadavez, V.; Gonzales-Barron, U.; Villena, I. Risk Factors for Sporadic Toxoplasmosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Microb. Risk Anal. 2021, 17, 100133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto-Ferreira, F.; Caldart, E.T.; Pasquali, A.K.S.; Mitsuka-Breganó, R.; Freire, R.L.; Navarro, I.T. Patterns of Transmission and Sources of Infection in Outbreaks of Human Toxoplasmosis. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2019, 25, 2177–2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Ureña, N.M.; Chaudhry, U.; Calero-Bernal, R.; Cano-Alsua, S.; Messina, D.; Evangelista, F.; Betson, M.; Lalle, M.; Jokelainen, P.; Ortega-Mora, L.M.; et al. Contamination of Soil, Water, Fresh Produce, and Bivalve Mollusks with Toxoplasma gondii Oocysts: A Systematic Review. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Álvarez-García, G.; Davidson, R.; Jokelainen, P.; Klevar, S.; Spano, F.; Seeber, F. Identification of Oocyst-Driven Toxoplasma gondii Infections in Humans and Animals through Stage-Specific Serology—Current Status and Future Perspectives. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 2346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; The PRISMA Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stroup, D.F.; Berlin, J.A.; Morton, S.C.; Olkin, I.; Williamson, G.D.; Rennie, D.; Moher, D.; Becker, B.J.; Sipe, T.A.; Thacker, S.B.; et al. Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology: A Proposal for Reporting. JAMA 2000, 283, 2008–2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebremedhin, E.Z.; Tadesse, G. A Meta-Analysis of the Prevalence of Toxoplasma gondii in Animals and Humans in Ethiopia. Parasit. Vectors 2015, 8, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.; Thompson, S.G. Quantifying Heterogeneity in a Meta-Analysis. Stat. Med. 2002, 21, 1539–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatam-Nahavandi, K.; Calero-Bernal, R.; Rahimi, M.T.; Pagheh, A.S.; Zarean, M.; Dezhkam, A.; Ahmadpour, E. Toxoplasma gondii Infection in Domestic and Wild Felids as Public Health Concerns: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 9509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birgisdóttir, A.; Ásbjörnsdóttir, H.; Cook, E.; Gislason, D.; Jansson, C.; Olafsson, I.; Gislason, T.; Jogi, R.; Thjodleifsson, B. Seroprevalence of Toxoplasma gondii in Sweden, Estonia and Iceland. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 2006, 38, 625–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lassen, B.; Janson, M.; Viltrop, A.; Neare, K.; Hütt, P.; Golovljova, I.; Tummeleht, L.; Jokelainen, P. Serological Evidence of Exposure to Globally Relevant Zoonotic Parasites in the Estonian Population. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0164142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suvisaari, J.; Torniainen-Holm, M.; Lindgren, M.; Härkänen, T.; Yolken, R.H. Toxoplasma gondii Infection and Common Mental Disorders in the Finnish General Population. J. Affect. Disord. 2017, 223, 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindgren, M.; Holm, M.; Markkula, N.; Härkänen, T.; Dickerson, F.; Yolken, R.H.; Suvisaari, J. Exposure to Common Infections and Risk of Suicide and Self-Harm: A Longitudinal General Population Study. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2020, 270, 829–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siponen, A.M.; Kinnunen, P.M.; Koort, J.; Kallio-Kokko, H.; Vapalahti, O.; Virtala, A.M.; Jokelainen, P. Toxoplasma gondii Seroprevalence in Veterinarians in Finland: Older Age, Living in the Countryside, Tasting Beef During Cooking and not Doing Small Animal Practice Associated with Seropositivity. Zoonoses Public Health 2019, 66, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ásbjöernsdóttir, H.; Sigurjónsd Ttir, R.B.; Sveinsd Ttir, S.V.; Birgisd Ttir, A.; Cook, E.; Gíslason, D.; Jansson, C.; Olafsson, I.; Gíslason, T.; Thornjóethleifsson, B. Algengi IgG mótefna gegn Toxoplasma gondii, Helicobacter pylori og lifrarbólguveiru A á Islandi. Tengsl vieth ofnaemi og lungnaeinkenni [Foodborne Infections in Iceland. Relationship to Allergy and Lung Function]. Laeknabladid 2006, 92, 437–444. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson, W.; Mayne, P.D.; Lennon, B.; Butler, K.; Cafferkey, M. Susceptibility of Pregnant Women to Toxoplasma Infection—Potential Benefits for Newborn Screening. Ir. Med. J. 2008, 101, 220–221. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, K.T.; Eskild, A.; Bresnahan, M.; Stray-Pedersen, B.; Sher, A.; Jenum, P.A. Previous Maternal Infection with Toxoplasma gondii and the Risk of Fetal Death. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2005, 193, 443–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, S.; Jenum, P.A.; Aukrust, P.; Rollag, H.; Andreassen, A.K.; Simonsen, S.; Gude, E.; Fiane, A.E.; Geiran, O.; Gullestad, L. Pre-Transplant Toxoplasma gondii Seropositivity among Heart Transplant Recipients is Associated with an Increased Risk of all-Cause and Cardiac Mortality. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2007, 50, 1967–1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eskild, A.; Fallås Dahl, G.; Melby, K.K.; Nesheim, B.I. Testing for Toxoplasmosis in Pregnancy: A Study of the Routines in Primary Antenatal Care. J. Med. Screen. 2003, 10, 172–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellertsen, L.K.; Hetland, G.; Løvik, M. Specific IgE to Respiratory Allergens and IgG Antibodies to Toxoplasma gondii and Streptococcus pneumoniae in Norwegian Military Recruits. Scand. J. Immunol. 2008, 67, 496–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bjerke, S.E.; Vangen, S.; Holter, E.; Stray-Pedersen, B. Infectious Immune Status in an Obstetric Population of Pakistani Immigrants in Norway. Scand. J. Public Health 2011, 39, 464–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Findal, G.; Barlinn, R.; Sandven, I.; Stray-Pedersen, B.; Nordbø, S.A.; Samdal, H.H.; Vainio, K.; Dudman, S.G.; Jenum, P.A. Toxoplasma Prevalence among Pregnant Women in Norway: A Cross-Sectional Study. APMIS 2015, 123, 321–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petersson, K.; Stray-Pedersen, B.; Malm, G.; Forsgren, M.; Evengård, B. Seroprevalence of Toxoplasma gondii among Pregnant Women in Sweden. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2000, 79, 824–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evengård, B.; Petersson, K.; Engman, M.L.; Wiklund, S.; Ivarsson, S.A.; Teär-Fahnehjelm, K.; Forsgren, M.; Gilbert, R.; Malm, G. Low Incidence of Toxoplasma Infection During Pregnancy and in Newborns in Sweden. Epidemiol. Infect. 2001, 127, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, H.V.; Thomas, D.R.; Salmon, R.L.; Lewis, G.; Smith, A.P. Toxoplasma and Coxiella Infection and Psychiatric Morbidity: A Retrospective Cohort Analysis. BMC Psychiatry 2004, 4, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nash, J.Q.; Chissel, S.; Jones, J.; Warburton, F.; Verlander, N.Q. Risk Factors for Toxoplasmosis in Pregnant Women in Kent, United Kingdom. Epidemiol. Infect. 2005, 133, 475–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flatt, A.; Shetty, N. Seroprevalence and Risk Factors for Toxoplasmosis among Antenatal Women in London: A Re-examination of Risk in an Ethnically Diverse Population. Eur. J. Public Health 2013, 23, 648–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burrells, A.; Opsteegh, M.; Pollock, K.G.; Alexander, C.L.; Chatterton, J.; Evans, R.; Walker, R.; McKenzie, C.A.; Hill, D.; Innes, E.A.; et al. The Prevalence and Genotypic Analysis of Toxoplasma gondii from Individuals in Scotland, 2006–2012. Parasit. Vectors 2016, 9, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCaughey, C.; Watt, A.P.; McCaughey, K.A.; Feeney, M.A.; Coyle, P.V.; Christie, S.N. Toxoplasma Seroprevalance in Northern Ireland. Ulster Med. J. 2017, 86, 43–44. [Google Scholar]

- Berghold, C.; Herzog, S.A.; Jakse, H.; Berghold, A. Prevalence and Incidence of Toxoplasmosis: A Retrospective Analysis of Mother-Child Examinations, Styria, Austria, 1995 to 2012. Euro Surveill. 2016, 21, 30317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juncker-Voss, M.; Prosl, H.; Lussy, H.; Enzenberg, U.; Auer, H.; Lassnig, H.; Müller, M.; Nowotny, N. Untersuchungen auf Antikörper gegen Zoonoseerreger bei Angestellten des Wiener Tiergartens Schönbrunn [Screening for Antibodies Against Zoonotic Agents among Employees of the Zoological Garden of Vienna, Schönbrunn, Austria]. Berl. Munch. Tierarztl. Wochenschr. 2004, 117, 404–409. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sagel, U.; Krämer, A.; Mikolajczyk, R.T. Incidence of Maternal Toxoplasma Infections in Pregnancy in Upper Austria, 2000-2007. BMC Infect. Dis. 2011, 11, 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prusa, A.R.; Kasper, D.C.; Olischar, M.; Husslein, P.; Pollak, A.; Hayde, M. Evaluation of Serological Prenatal Screening to Detect Toxoplasma gondii Infections in Austria. Neonatology 2013, 103, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breugelmans, M.; Naessens, A.; Foulon, W. Prevention of Toxoplasmosis During Pregnancy-An Epidemiologic Survey over 22 Consecutive Years. J. Perinat. Med. 2004, 32, 211–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berger, F.; Goulet, V.; Le Strat, Y.; Desenclos, J.C. Toxoplasmosis among Pregnant Women in France: Risk Factors and Change of Prevalence Between 1995 and 2003. Rev. Epidemiol. Sante Publique 2009, 57, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nogareda, F.; Le Strat, Y.; Villena, I.; De Valk, H.; Goulet, V. Incidence and Prevalence of Toxoplasma gondii Infection in Women in France, 1980-2020: Model-Based Estimation. Epidemiol. Infect. 2014, 142, 1661–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guigue, N.; Léon, L.; Hamane, S.; Gits-Muselli, M.; Le Strat, Y.; Alanio, A.; Bretagne, S. Corrigendum: Guigue et al. Continuous Decline of Toxoplasma gondii Seroprevalence in Hospital: A 1997–2014 Longitudinal Study in Paris, France. Front Microbiol. 2018, 9, 2369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonnet, F.; Lewden, C.; May, T.; Heripret, L.; Jougla, E.; Bevilacqua, S.; Costagliola, D.; Salmon, D.; Chêne, G.; Morlat, P.; et al. Opportunistic Infections as Causes of Death in HIV-Infected Patients in the HAART Era in France. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 2005, 37, 482–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilot-Fromont, E.; Riche, B.; Rabilloud, M. Toxoplasma Seroprevalence in a Rural Population in France: Detection of a Household Effect. BMC Infect. Dis. 2009, 9, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellali, H.; Pelloux, H.; Villena, I.; Fricker-Hidalgo, H.; Le Strat, Y.; Goulet, V. Prevalence of Toxoplasmosis in France in 1998: Is There a Difference Between Men and Women? At What Age do Children Become Infected? Rev. Epidemiol. Sante Publique 2013, 61, 311–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilking, H.; Thamm, M.; Stark, K.; Aebischer, T.; Seeber, F. Prevalence, Incidence Estimations, and Risk Factors of Toxoplasma gondii Infection in Germany: A Representative, Cross-Sectional, Serological Study. Sci Rep. 2016, 6, 22551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lange, A.E.; Thyrian, J.R.; Wetzka, S.; Flessa, S.; Hoffmann, W.; Zygmunt, M.; Fusch, C.; Lode, H.N.; Heckmann, M. The Impact of Socioeconomic Factors on the Efficiency of Voluntary Toxoplasmosis Screening During Pregnancy: A Population-Based Study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2016, 16, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kortbeek, L.M.; De Melker, H.E.; Veldhuijzen, I.K.; Conyn-Van Spaendonck, M.A. Population-Based Toxoplasma Seroprevalence Study in The Netherlands. Epidemiol. Infect. 2004, 132, 839–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hofhuis, A.; van Pelt, W.; van Duynhoven, Y.T.; Nijhuis, C.D.; Mollema, L.; van der Klis, F.R.; Havelaar, A.H.; Kortbeek, L.M. Decreased Prevalence and Age-Specific Risk Factors for Toxoplasma gondii IgG Antibodies in The Netherlands Between 1995/1996 and 2006/2007. Epidemiol. Infect. 2011, 139, 530–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Signorell, L.M.; Seitz, D.; Merkel, S.; Berger, R.; Rudin, C. Cord Blood Screening for Congenital Toxoplasmosis in Northwestern Switzerland, 1982–1999. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2006, 25, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudin, C.; Hirsch, H.H.; Spaelti, R.; Schaedelin, S.; Klimkait, T. Decline of Seroprevalence and Incidence of Congenital Toxoplasmosis Despite Changing Prevention Policy-Three Decades of Cord-Blood Screening in North-Western Switzerland. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2018, 37, 1087–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodym, P.; Hrdá, S.; Machala, L.; Rozsypal, H.; Staňková, M.; Malý, M. Prevalence and Incidence of Toxoplasma Infection in HIV-Positive Patients in the Czech Republic. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 2006, 53, S160–S161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machala, L.; Malý, M.; Beran, O.; Jilich, D.; Kodym, P. Incidence and Clinical and Immunological Characteristics of Primary Toxoplasma gondii Infection in HIV-Infected Patients. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2013, 17, E892–E896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolbekova, P.; Kourbatova, E.; Novotna, M.; Kodym, P.; Flegr, J. New and Old Risk-Factors for Toxoplasma gondii Infection: Prospective Cross-Sectional Study among Military Personnel in the Czech Republic. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2007, 13, 1012–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skallová, A.; Novotná, M.; Kolbeková, P.; Gasová, Z.; Veselý, V.; Sechovská, M.; Flegr, J. Decreased Level of Novelty Seeking in Blood Donors Infected with Toxoplasma. Neuro Endocrinol. Lett. 2005, 26, 480–486. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Veleminsky, M., Jr.; Veleminsky, M., Sr.; Fajfrlik, K.; Kolarova, L. Importance of Screening Serological Examination of Umbilical Blood and the Blood of the Mother for Timely Diagnosis of Congenital Toxoplasmosis and Toxocariasis. Neuro Endocrinol. Lett. 2010, 31, 310–312. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Szénási, Z.; Horváth, K.; Sárkány, E.; Melles, M. Toxoplasmosis Surveillance During Pregnancy and Quality Assurance of Methods in Hungary. Wien. Klin. Wochenschr. 2005, 117, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dymon, M.; Kempińska, A. Ocena przydatności badań serologicznych w profilaktyce wrodzonej toksoplazmozy w materiałach Zakładu Parazytologii CM UJ [Evaluation of the Usefulness of Serological Examinations in the Prophylaxis of Congenital Toxoplasmosis in the Materials of CM UJ Parasitology Department]. Wiad. Parazytol. 2001, 47, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kurnatowska, A.; Tomczewska, I. Prewalencja Toxoplasma gondii oraz analiza stezenia swoistych immunoglobulin w surowicy kobiet w okresie rozrodczym w próbie populacji Włocławka [Prevalence of Toxoplasma gondii and Analysis of Specific Immunoglobulins Concentration in Serum of Women During the Reproductive Period in a Sample of Włocławek Population]. Wiad. Parazytol. 2001, 47, 77–82. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nowakowska, D.; Slaska, M.; Kostrzewska, E.; Wilczyński, J. Stezenie przeciwciał anty -T. gondii w surowicy kobiet ciezarnych w próbie populacji regionu lódzkiego w roku 1998 [Anti—T. gondii Antibody Concentration in Sera of Pregnant Women in the Sample of Lódź Population]. Wiad. Parazytol. 2001, 47, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Paul, M.; Petersen, E.; Szczapa, J. Prevalence of Congenital Toxoplasma gondii Infection among Newborns from the Poznań Region of Poland: Validation of a New Combined Enzyme Immunoassay for Toxoplasma gondii-Specific Immunoglobulin A and Immunoglobulin M Antibodies. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2001, 39, 1912–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowakowska, D.; Stray-Pedersen, B.; Spiewak, E.; Sobala, W.; Małafiej, E.; Wilczyński, J. Prevalence and Estimated Incidence of Toxoplasma Infection among Pregnant Women in Poland: A Decreasing Trend in the Younger Population. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2006, 12, 913–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemiec, K.T.; Raczyński, P.; Markiewicz, K.; Leibschang, J.; Ceran, A. Czestość wystepowania zarazeń pierwotniakiem Toxoplasma gondii u 2016 kobiet ciezarnych oraz ich dzieci urodzonych w Instytucie Matki i Dziecka w Warszawie [The Prevalence of Toxoplasma gondii Infection among 2016 Pregnant Women and their Children in the Institute of Mother and Child in Warsaw]. Wiad. Parazytol. 2002, 48, 293–299. [Google Scholar]

- Spausta, G.; Gorczyńska, D.; Ciarkowska, J.; Wiczkowski, A.; Krzanowska, E.; Gawron, K. Wystepowanie pasozytów człowieka w wybranych populacjach na przykładzie badań przeprowadzonych w Slqskiej Wojewódzkiej Stacji Sanitarno-Epidemiologicznej [Frequency of Human Parasites in Selected Populations of Silesian Region]. Wiad. Parazytol. 2005, 51, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Holec-Gasior, L.; Stańczak, J.; Myjak, P.; Kur, J. Wystepowanie specyficznych przeciwciał anty-Toxoplasma gondii w grupie pracowników leśnych z województwa pomorskiego i warmińsko-mazurskiego [Occurrence of Toxoplasma gondii Specific Antibodies in Group of Forestry Workers from Pomorskie and Warmińsko-Mazurskie Provinces]. Wiad. Parazytol. 2008, 54, 231–236. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nowakowska, D.; Wujcicka, W.; Sobala, W.; Śpiewak, E.; Gaj, Z.; Wilczyński, J. Age-Associated Prevalence of Toxoplasma gondii in 8281 Pregnant Women in Poland Between 2004 and 2012. Epidemiol. Infect. 2014, 142, 656–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pityńska-Kumik, G.; Rewicka, M.; Heczko, P.B. Badania serologiczne przeprowadzone w kierunku toksoplazmozy w pracowni diagnostyki mikrobiologicznej cmuj w roku 2005 [Serologic Researches Conducted Towards Toxoplasmosis in the Department of Microbiology of Jagiellonian University Medical College in 2005 Year]. Med. Dosw. Mikrobiol. 2010, 62, 171–179. [Google Scholar]

- Zajkowska, A.; Garkowski, A.; Czupryna, P.; Moniuszko, A.; Król, M.E.; Szamatowicz, J.; Pancewicz, S. Seroprevalence of Parvovirus B19 Antibodies among Young Pregnant Women or Planning Pregnancy, Tested for Toxoplasmosis. Przegl. Epidemiol. 2015, 69, 479–482. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Holec-Gasior, L.; Kur, J. Badania epidemiologiczne populacji kobiet gminy Przodkowo w kierunku toksoplazmozy [Epidemiological studies of toxoplasmosis among women from Przodkowo commune]. Przegl. Epidemiol. 2009, 63, 311–316. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Samojłowicz, D.; Borowska-Solonynko, A.; Gołab, E. Prevalence of Toxoplasma gondii Parasite Infection among People who Died due to Sudden Death in the Capital City of Warsaw and its Vicinity. Przegl. Epidemiol. 2013, 67, 29–33. [Google Scholar]

- Salamon, D.; Bulanda, M. Toxoplasma gondii and Women of Reproductive Age: An Analysis of Data from the Chair of Microbiology, Jagiellonian University Medical College in Cracow. Ann. Parasitol. 2014, 60, 291–296. [Google Scholar]

- Tokarska-Rodak, M.; Weiner, M.; Szymańska-Czerwińska, M.; Pańczuk, A.; Niemczuk, K.; Sroka, J.; Różycki, M.; Iwaniak, W. Seroprevalence of Selected Zoonotic Agents among Hunters from Eastern Poland. Pol. J. Microbiol. 2018, 67, 233–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czyzewski, K.; Fraczkiewicz, J.; Salamonowicz, M.; Pieczonka, A.; Zajac-Spychala, O.; Zaucha-Prazmo, A.; Gozdzik, J.; Styczynski, J. Low Seroprevalence and Low Incidence of Infection with Toxoplasma gondii (Nicolle et Manceaux, 1908) in Pediatric Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation Donors and Recipients: Polish Nationwide Study. Folia Parasitol. 2019, 66, 2019.019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biskupska, M.; Kujawa, A.; Wysocki, J. Preventing Congenital Toxoplasmosis—Implementation of Clinical Practice Guidelines. Ginekol. Pol. 2018, 89, 388–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wójcik-Fatla, A.; Sroka, J.; Zając, V.; Zwoliński, J.; Sawczyn-Domańska, A.; Kloc, A.; Bilska-Zając, E.; Chmura, R.; Dutkiewicz, J. Study on Toxoplasma gondii, Leptospira spp., Coxiella burnetii, and Echinococcus granulosus Infection in Veterinarians from Poland. J. Vet. Res. 2018, 62, 477–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sroka, J. Seroepidemiology of Toxoplasmosis in the Lublin Region. Ann. Agric. Environ. Med. 2001, 8, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sroka, J.; Zwoliński, J.; Dutkiewicz, J. Czekstość wystepowania przeciwciał anty-Toxoplasma gondii wśród pracowników Zakładów Miesnych w Lublinie [The Prevalence of Anti-Toxoplasma gondii Antibodies among Abattoir Workers in Lublin]. Wiad. Parazytol. 2003, 49, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sroka, J.; Wójcik-Fatla, A.; Szymanska, J.; Dutkiewicz, J.; Zając, V.; Zwoliński, J. The Occurrence of Toxoplasma gondii Infection in People and Animals from Rural Environment of Lublin Region—Estimate of Potential Role of Water as a Source of Infection. Ann. Agric. Environ. Med. 2010, 17, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mizgajska-Wiktor, H.; Jarosz, W.; Andrzejewska, I.; Krzykała, M.; Janowski, J.; Kozłowska, M. Differences in Some Developmental Features Between Toxoplasma gondii-Seropositive and Seronegative School Children. Folia Parasitol. 2013, 60, 416–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teodorescu, C.; Manea, V.; Teodorescu, I. Toxoplasma gondii Diagnosis in Pregnant Women by PCR and ELISA Technics. Rev. Rom. Parazitol. 2007, 17, 37–41. [Google Scholar]

- Costache, C.A.; Ţigan, Ş.I.; Colosi, I.; Coroiu, Z. Toxoplasmic Infection in Pregnant Women from Cluj County and Neighbouring Area. Appl. Med. Inform. 2008, 23, 31–36. [Google Scholar]

- Coroiu, Z.; Radu, R.; Molnar, A.; Bele, J. Seroprevalence of Anti-Toxoplasma gondii Antibodies in the Healthy Population from North-Estern and Central Romania. Sc. Parasit. 2009, 10, 37–42. [Google Scholar]

- Olariu, T.R.; Petrescu, C.; Darabus, G.; Lighezan, R.; Mazilu, O. Seroprevalence of Toxoplasma gondii in Western Romania. Infect. Dis. 2015, 47, 580–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messinger, C.J.; Gurzau, E.S.; Breitschwerdt, E.B.; Tomuleasa, C.I.; Trufan, S.J.; Flonta, M.M.; Maggi, R.G.; Berindan-Neagoe, I.; Rabinowitz, P.M. Seroprevalence of Bartonella Species, Coxiella burnetii and Toxoplasma gondii among Patients with Hematological Malignancies: A Pilot Study in Romania. Zoonoses Public Health 2017, 64, 485–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Căpraru, I.D.; Lupu, M.A.; Horhat, F.; Olariu, T.R. Toxoplasmosis Seroprevalence in Romanian Children. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2019, 19, 867–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olariu, T.R.; Darabus, G.H.; Cretu, O.; Jurovits, O.; Giura, E.; Erdelean, V.; Marincu, I.; Iacobiciu, I.; Petrescu, C.; Koreck, A. Prevalence of Toxoplasma gondii Antibodies among Women of Childbearing Age in Timis County. Lucr. Stiint. Med. Vet. Timis. 2008, 41, 367–371. [Google Scholar]

- Zemlianskiĭ, O.A. O seroépidemiologii toksoplazmoza u beremennykh zhenshchin i novorozhdennykh [Seroepidemiology of Toxoplasmosis in Pregnant Women and Neonatal Infants]. Med. Parazitol. 2004, 3, 40–42. [Google Scholar]

- Dolgikh, T.I.; Zapariĭ, N.S.; Kadtsyna, T.V.; Kalitin, A.V. Epidemiological and Clinicoimmunological Monitoring of Toxoplasmosis in the Omsk Region. Med. Parazitol. 2008, 1, 19–22. [Google Scholar]

- Shakhgil’dian, V.I.; Vasil’eva, T.E.; Peregudova, A.B.; Gruzdev, B.M.; Danilova, T.V.; Martynova, N.N.; Filippov, P.G.; Litvinova, N.G.; Pavlova, L.E.; Tishkevich, O.A.; et al. Spectrum, Clinical Features, Diagnosis of Opportunistic and Comorbid Pathology in HIV-Infected Patients Admitted to Infection Hospital of Moscow. Ter. Arkh. 2008, 80, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Magnaval, J.F.; Leparc-Goffart, I.; Gibert, M.; Gurieva, A.; Outreville, J.; Dyachkovskaya, P.; Fabre, R.; Fedorova, S.; Nikolaeva, D.; Dubois, D.; et al. A Serological Survey About Zoonoses in the Verkhoyansk Area, Northeastern Siberia (Sakha Republic, Russian Federation). Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2016, 16, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuralev, E.A.; Shamaev, N.D.; Mukminov, M.N.; Nagamune, K.; Taniguchi, Y.; Saito, T.; Kitoh, K.; Arleevskaya, M.I.; Fedotova, A.Y.; Abdulmanova, D.R.; et al. Toxoplasma gondii Seroprevalence in Goats, Cats and Humans in Russia. Parasitol. Int. 2018, 67, 112–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepanova, E.V.; Kondrashin, A.V.; Sergiev, V.P.; Morozova, L.F.; Turbabina, N.A.; Maksimova, M.S.; Brazhnikov, A.I.; Shevchenko, S.B.; Morozov, E.N. Significance of Chronic Toxoplasmosis in Epidemiology of Road Traffic Accidents in Russian Federation. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0184930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Studenicová, C.; Ondriska, F.; Holková, R. Séroprevalencia Toxoplasma gondii u gravidných zien na Slovensku [Seroprevalence of Toxoplasma gondii among Pregnant Women in Slovakia]. Epidemiol. Mikrobiol. Imunol. 2008, 57, 8–13. [Google Scholar]

- Studenicová, C.; Bencaiová, G.; Holková, R. Seroprevalence of Toxoplasma gondii Antibodies in a Healthy Population from Slovakia. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2006, 17, 470–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luptáková, L.; Petrovová, E. The Occurrence of Microsporidial Infections and Toxoplasmosis in Slovak Women. Epidemiol. Mikrobiol. Imunol. 2011, 60, 156–160. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Strhársky, J.; Klement, C.; Hrubá, F. Seroprevalence of Toxoplasma gondii Antibodies in the Slovak Republic. Folia Microbiol. 2009, 54, 553–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antolová, D.; Janičko, M.; Halánová, M.; Jarčuška, P.; Gecková, A.M.; Babinská, I.; Kalinová, Z.; Pella, D.; Mareková, M.; Veseliny, E.; et al. Exposure to Toxoplasma gondii in the Roma and Non-Roma Inhabitants of Slovakia: A Cross-Sectional Seroprevalence Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fecková, M.; Antolová, D.; Janičko, M.; Monika, H.; Štrkolcová, G.; Goldová, M.; Weissová, T.; Lukáč, B.; Nováková, M. The Cross-Sectional Study of Toxoplasma gondii Seroprevalence in Selected Groups of Population in Slovakia. Folia Microbiol. 2020, 65, 871–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maggi, P.; Volpe, A.; Carito, V.; Schinaia, N.; Bino, S.; Basho, M.; Dentico, P. Surveillance of Toxoplasmosis in Pregnant Women in Albania. New Microbiol. 2009, 32, 89–92. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bobić, B.; Milosavić, M.; Guzijan, G.; Djurković-Djaković, O. First Report on Toxoplasma gondii Infection in Bosnia and Herzegovina: Study in Blood Donors. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2016, 16, 807–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punda-Polić, V.; Tonkić, M.; Capkun, V. Prevalence of Antibodies to Toxoplasma gondii in the Female Population of the County of Split Dalmatia, Croatia. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2000, 16, 875–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonkić, M.; Punda-Polić, V.; Sardelić, S.; Capkun, V. Ucestalost protutijela za Toxoplasmu gondii u populaciji splitsko-dalmatinske zupanije [Occurrence of Toxoplasma gondii Antibodies in the Population of Split-Dalmatia County]. Lijec. Vjesn. 2002, 124, 19–22. [Google Scholar]

- Đaković-Rode, O.; Židovec-Lepej, S.; Vodnica-Martucci, M.; Lasica-Polanda, V.; Begovac, J. Prevalencija protutijela na Toxoplasma gondii u bolesnika zara`enih virusom humane imunodeficijencije u Hrvatskoj [Prevalence of Antibodies against Toxoplasma gondii in Patients Infected with Human Immunodeficiency Virus in Croatia]. Croat. J. Infect. 2010, 30, 5–10. [Google Scholar]

- Vilibic-Cavlek, T.; Ljubin-Sternak, S.; Ban, M.; Kolaric, B.; Sviben, M.; Mlinaric-Galinovic, G. Seroprevalence of TORCH Infections in Women of Childbearing Age in Croatia. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2011, 24, 280–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liassides, M.; Christodoulou, V.; Moschandreas, J.; Karagiannis, C.; Mitis, G.; Koliou, M.; Antoniou, M. Toxoplasmosis in Female High School Students, Pregnant Women and Ruminants in Cyprus. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2016, 110, 359–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diza, E.; Frantzidou, F.; Souliou, E.; Arvanitidou, M.; Gioula, G.; Antoniadis, A. Seroprevalence of Toxoplasma gondii in Northern Greece during the last 20 Years. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2005, 11, 719–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antoniou, M.; Economou, I.; Wang, X.; Psaroulaki, A.; Spyridaki, I.; Papadopoulos, B.; Christidou, A.; Tsafantakis, E.; Tselentis, Y. Fourteen-Year Seroepidemiological Study of Zoonoses in a Greek Village. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2002, 66, 80–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antoniou, M.; Tzouvali, H.; Sifakis, S.; Galanakis, E.; Georgopoulou, E.; Liakou, V.; Giannakopoulou, C.; Koumantakis, E.; Tselentis, Y. Incidence of Toxoplasmosis in 5532 Pregnant Women in Crete, Greece: Management of 185 Cases at Risk. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2004, 117, 138–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antoniou, M.; Tzouvali, H.; Sifakis, S.; Galanakis, E.; Georgopoulou, E.; Tselentis, Y. Toxoplasmosis in Pregnant Women in Crete. Parassitologia 2007, 49, 231–233. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ricci, M.; Pentimalli, H.; Thaller, R.; Ravà, L.; Di Ciommo, V. Screening and Prevention of Congenital Toxoplasmosis: An Effectiveness Study in a Population with a High Infection Rate. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2003, 14, 398–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruffini, E.; Compagnoni, L.; Tubaldi, L.; Infriccioli, G.; Vianelli, P.; Genga, R.; Bonifazi, V.; Dieni, A.; Guerrini, D.; Basili, G.; et al. Le infezioni congenite e perinatali nella regione Marche (Italia). Studio epidemiologico e differenze tra gruppi etnici [Congenital and Perinatal Infections in the Marche Region (Italy): An Epidemiological Study and Differences between Ethnic Groups]. Infez. Med. 2014, 22, 213–221. [Google Scholar]

- De Paschale, M.; Agrappi, C.; Clerici, P.; Mirri, P.; Manco, M.T.; Cavallari, S.; Viganò, E.F. Seroprevalence and Incidence of Toxoplasma gondii Infection in the Legnano Area of Italy. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2008, 14, 186–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masini, L.; Casarella, L.; Grillo, R.L.; Zannella, M.P.; Oliva, G.C. Epidemiologic Study on Anti-Toxoplasma gondii Antibodies Prevalence in an Obstetric Population. It. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2008, 20, 159–166. [Google Scholar]

- Tomasoni, L.R.; Sosta, E.; Beltrame, A.; Rorato, G.; Bigoni, S.; Frusca, T.; Zanardini, C.; Driul, L.; Magrini, F.; Viale, P.; et al. Antenatal Screening for Mother to Child Infections in Immigrants and Residents: The Case of Toxoplasmosis in Northern Italy. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2010, 12, 834–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thaller, R.; Tammaro, F.; Pentimalli, H. Fattori di rischio per latoxoplasmosi in gravidanzain una popolazione del centro Italia [Risk Factors for Toxoplasmosis in Pregnant Women in Central Italy]. Infez. Med. 2011, 19, 241–247. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pinto, B.; Castagna, B.; Mattei, R.; Bruzzi, R.; Chiumiento, L.; Cristofani, R.; Buffolano, W.; Bruschi, F. Seroprevalence for Toxoplasmosis in Individuals Living in North West Tuscany: Access to Toxo-Test in Central Italy. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2012, 31, 1151–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mosti, M.; Pinto, B.; Giromella, A.; Fabiani, S.; Cristofani, R.; Panichi, M.; Bruschi, F. A 4-Year Evaluation of Toxoplasmosis Seroprevalence in the General Population and in Women of Reproductive Age in Central Italy. Epidemiol. Infect. 2013, 141, 2192–2195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalmartello, M.; Parazzini, F.; Pedron, M.; Pertile, R.; Collini, L.; La Vecchia, C.; Piffer, S. Coverage and Outcomes of Antenatal Tests for Infections: A Population Based Survey in the Province of Trento, Italy. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2019, 32, 2049–2055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piffer, S.; Lauriola, A.L.; Pradal, U.; Collini, L.; Dell’Anna, L.; Pavanello, L. Toxoplasma gondii Infection During Pregnancy: A Ten-Year Observation in the Province of Trento, Italy. Infez. Med. 2020, 28, 603–610. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Capretti, M.G.; De Angelis, M.; Tridapalli, E.; Orlandi, A.; Marangoni, A.; Moroni, A.; Guerra, B.; Arcuri, S.; Marsico, C.; Faldella, G. Toxoplasmosis in Pregnancy in an Area with Low Seroprevalence: Is Prenatal Screening Still Worthwhile? Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2014, 33, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, B.; Mattei, R.; Moscato, G.A.; Cristofano, M.; Giraldi, M.; Scarpato, R.; Buffolano, W.; Bruschi, F. Toxoplasma Infection in Individuals in Central Italy: Does a Gender-Linked Risk Exist? Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2017, 36, 739–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decembrino, N.; Comelli, A.; Genco, F.; Vitullo, A.; Recupero, S.; Zecca, M.; Meroni, V. Toxoplasmosis Disease in Paediatric Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation: Do not Forget it Still Exists. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2017, 52, 1326–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puccio, G.; Cajozzo, C.; Canduscio, L.A.; Cino, L.; Romano, A.; Schimmenti, M.G.; Giuffrè, M.; Corsello, G. Epidemiology of Toxoplasma and CMV Serology and of GBS Colonization in Pregnancy and Neonatal Outcome in a Sicilian Population. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2014, 40, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanigliulo, D.; Marchi, S.; Montomoli, E.; Trombetta, C.M. Toxoplasma gondii in Women of Childbearing Age and during Pregnancy: Seroprevalence Study in Central and Southern Italy from 2013 to 2017. Parasite 2020, 27, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cvetković, D.; Bobić, B.; Jankovska, G.; Klun, I.; Panovski, N.; Djurković-Djaković, O. Risk Factors for Toxoplasma Infection in Pregnant Women in FYR of Macedonia. Parasite 2010, 17, 183–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrade, J.V.; Resende, C.; Campos, J.; Batista, C.; Faria, C.; Figueiredo, C.; Bastos, V.; Andrade, N.; Andrade, I. Recém-Nascidos com Risco de Toxoplasmose Congênita, Revisão de 16 Anos [Newborns at Risk for Congenital Toxoplasmosis, Review of 16 Years]. Sci. Med. 2018, 28, 32169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gargaté, M.J.; Ferreira, I.; Vilares, A.; Martins, S.; Cardoso, C.; Silva, S.; Nunes, B.; Gomes, J.P. Toxoplasma gondii Seroprevalence in the Portuguese Population: Comparison of three Cross-Sectional Studies Spanning three Decades. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e011648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lito, D.; Francisco, T.; Salva, I.; Tavares, M.d.N.; Oliveira, R.; Neto, M.T. TORCH Serology and Group B Streptococcus Screening Analysis in the Population of a Maternity. Acta Med. Port. 2013, 26, 549–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopes, A.P.; Dubey, J.P.; Moutinho, O.; Gargaté, M.J.; Vilares, A.; Rodrigues, M.; Cardoso, L. Seroepidemiology of Toxoplasma gondii Infection in Women from the North of Portugal in their Childbearing Years. Epidemiol. Infect. 2012, 140, 872–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lobo, M.L.; Patrocinio, G.; Sevivas, T.; de Sousa, B.; Matos, O. Portugal and Angola: Similarities and Differences in Toxoplasma gondii Seroprevalence and Risk Factors in Pregnant Women. Epidemiol. Infect. 2017, 145, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobić, B.; Nikolić, A.; Klun, I.; Vujanić, M.; Djurković-Djaković, O. Undercooked Meat Consumption Remains the Major Risk Factor for Toxoplasma Infection in Serbia. Parassitologia 2007, 49, 227–230. [Google Scholar]

- Dentico, P.; Volpe, A.; Putoto, G.; Ramadani, N.; Bertinato, L.; Berisha, M.; Schinaia, N.; Quaglio, G.; Maggi, P. Toxoplasmosis in Kosovo Pregnant Women. New Microbiol. 2011, 34, 203–207. [Google Scholar]

- Pribakovic, J.A.; Katanic, N.; Radevic, T.; Tasic, M.S.; Kostic, M.; Stolic, B.; Radulovic, A.; Minic, V.; Bojovic, K.; Katanic, R. Serological Status of Childbearing-Aged Women for Toxoplasma gondii and Cytomegalovirus in Northern Kosovo and Metohija. Rev. Soc. Bras. Med. Trop. 2019, 52, e20170313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerant, P.V.; Milosević, V.; Hrnjaković Cvjetković, I.; Patić, A.; Stefan Mikić, S.; Ristić, M. Infekcije Toksoplazmom gondii kod Gravidnih Žena [Toxoplasma gondii Infection in Pregnant Women]. Med. Pregl. 2013, 66, 459–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Logar, J.; Kraut, A.; Stirn-Kranjc, B.; Vidovic-Valentincic, N. Seroprevalence of Toxoplasma Antibodies among Patients with Ocular Disease in Slovenia. J. Infect. 2003, 46, 73–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Logar, J.; Petrovec, M.; Novak-Antolic, Z.; Premru-Srsen, T.; Cizman, M.; Arnez, M.; Kraut, A. Prevention of Congenital Toxoplasmosis in Slovenia by Serological Screening of Pregnant Women. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 2002, 34, 201–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vírseda-Chamorro, I.; Jaqueti-Aroca, J.; Prieto-Carbajo, R.I.; Vico-Cano, J. Prevalencia de Toxoplasmosis Materno-Fetal. Estudio de 15 años (1987–2001) [Prevalence of Maternal-Fetal Toxoplasmosis. A 15-Year Study (1987–2001)]. Rev. Clin. Esp. 2004, 204, 292–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pujol-Riqué, M.; Quintó, L.; Danés, C.; Valls, M.E.; Coll, O.; Jiménez de Anta, M.T. Seroprevalencia de la Toxoplasmosis en Mujeres en Edad Fértil (1992–1999) [Seroprevalence of Toxoplasmosis in Women of Childbearing Age (1992–1999)]. Med. Clin. 2000, 115, 375–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roc, M.L.; Palacián, M.P.; Lomba, E.; Monforte, M.L.; Rebaje, V.; Revillo-Pinilla, M.J. Diagnóstico Serológico de los Casos de Toxoplasmosis Congénita [Serologic Diagnosis of Congenital Toxoplasmosis]. Enferm. Infecc. Microbiol. Clin. 2010, 28, 517–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alonso, R.; Martínez, E.; Laynez, P.; Miguélez, M.; Piñero, J.E.; Valladares, B. Detección Mediante Reacción en Cadena de la Polimerasa Anidada de Toxoplasma gondii en Pacientes con Infección por el Virus de la Inmunodeficiencia Humana [Detection by Nested-PCR of Toxoplasma gondii in Patients Infected with Human Immunodeficiency Virus]. Med. Clin. 2002, 118, 294–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Batet, C.; Guardià-Llobet, C.; Juncosa-Morros, T.; Viñas-Domenech, L.; Sierra-Soler, M.; Sanfeliu-Sala, I.; Bosch-Mestres, J.; Dopico-Ponte, E.; Lite-Lite, J.; Matas-Andreu, L.; et al. Toxoplasmosis y Embarazo. Estudio Multicéntrico Realizado en 16.362 Gestantes de Barcelona [Toxoplasmosis and Pregnancy. Multicenter Study of 16,362 Pregnant Women in Barcelona]. Med. Clin. 2004, 123, 12–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Zufiaurre, N.; Sánchez-Hernández, J.; Muñoz, S.; Marín, R.; Delgado, N.; Sáenz, M.C.; Muñoz-Bellido, J.L.; García-Rodríguez, J.A. Seroprevalencia de Anticuerpos Frente a Treponema pallidum, Toxoplasma gondii, Virus de la Rubéola, Virus de la Hepatitis B y C y VIH en Mujeres Gestantes [Seroprevalence of Antibodies against Treponema pallidum, Toxoplasma gondii, Rubella Virus, Hepatitis B and C Virus, and HIV in Pregnant Women]. Enferm. Infecc. Microbiol. Clin. 2004, 22, 512–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asencio, M.A.; Herraez, O.; Tenias, J.M.; Garduño, E.; Huertas, M.; Carranza, R.; Ramos, J.M. Seroprevalence Survey of Zoonoses in Extremadura, Southwestern Spain, 2002–2003. Jpn. J. Infect. Dis. 2015, 68, 106–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, J.M.; Milla, A.; Rodríguez, J.C.; Gutiérrez, F. Seroprevalencia Frente a Toxoplasma gondii, Virus de la Rubéola, Virus de la Hepatitis B, VIH y Sífilis en Gestantes Extranjeras en Elche y Comarca [Seroprevalence of Antibodies against Toxoplasma gondii, Rubella Virus, Hepatitis B Virus, HIV and Treponema pallidum in Foreign Pregnant Women in Elche (Spain)]. Med. Clin. 2007, 129, 677–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartolomé-Álvarez, J.; Martínez-Serrano, M.; Moreno-Parrado, L.; Lorente-Ortuño, S.; Crespo-Sánchez, M.D. Prevalencia e Incidencia de la Infección por Toxoplasma gondii en Mujeres en Edad Fértil en Albacete (2001–2007) [Prevalence and Incidence in Albacete, Spain, of Toxoplasma gondii Infection in Women of Childbearing Age: Differences between Immigrant and Non-Immigrant (2001–2007)]. Rev. Esp. Salud Publica 2008, 82, 333–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos, J.M.; Milla, A.; Rodríguez, J.C.; Padilla, S.; Masiá, M.; Gutiérrez, F. Seroprevalence of Toxoplasma gondii Infection among Immigrant and Native Pregnant Women in Eastern Spain. Parasitol. Res. 2011, 109, 1447–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sampedro, A.; Mazuelas, P.; Rodríguez-Granger, J.; Torres, E.; Puertas, A.; Navarro, J.M. Marcadores Serológicos en Gestantes Inmigrantes y Autóctonas en Granada [Serological Markers in Immigrant and Spanish Pregnant Women in Granada]. Enferm. Infecc. Microbiol. Clin. 2010, 28, 694–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santiago, B.; Blázquez, D.; López, G.; Sainz, T.; Muñoz, M.; Alonso, T.; Moro, M. Perfil Serológico en Gestantes Extranjeras Frente a VIH, VHB, VHC, Virus de la Rubéola, Toxoplasma gondii, Treponema pallidum, y Trypanosoma cruzi [Serological Profile of Immigrant Pregnant Women against HIV, HBV, HCV, Rubella, Toxoplasma gondii, Treponema pallidum, and Trypanosoma cruzi]. Enferm. Infecc. Microbiol. Clin. 2012, 30, 64–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Fabal, F.; Gómez-Garcés, J.L. Marcadores Serológicos de Gestantes Españolas e Inmigrantes en un Área del Sur de Madrid Durante el Periodo 2007–2010 [Serological markers of Spanish and Immigrant Pregnant Women in the South of Madrid During the Period 2007–2010]. Rev. Esp. Quimioter. 2013, 26, 108–111. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, D.R.; Hogh, B.; Andersen, O.; Fuchs, J.; Fledelius, H.; Petersen, E. The National Neonatal Screening Programme for Congenital Toxoplasmosis in Denmark: Results from the Initial Four Years, 1999–2002. Arch. Dis. Child. 2006, 91, 661–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Röser, D.; Nielsen, H.V.; Petersen, E.; Saugmann-Jensen, P.; Nørgaard-Pedersen, B. Congenital Toxoplasmosis—A Report on the Danish Neonatal Screening Programme 1999–2007. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2010, 33, 241–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahnehjelm, K.T.; Malm, G.; Ygge, J.; Engman, M.L.; Maly, E.; Evengård, B. Ophthalmological Findings in Children with Congenital Toxoplasmosis. Report from a Swedish Prospective Screening Study of Congenital Toxoplasmosis with two Years of Follow-Up. Acta Ophthalmol. Scand. 2000, 78, 569–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagel, U.; Mikolajczyk, R.T.; Krämer, A. Seasonal Trends in Acute Toxoplasmosis in Pregnancy in the Federal State of Upper Austria. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2010, 16, 515–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kortbeek, L.M.; Hofhuis, A.; Nijhuis, C.D.; Havelaar, A.H. Congenital Toxoplasmosis and DALYs in the Netherlands. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 2009, 104, 370–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paul, M.; Petersen, E.; Pawlowski, Z.S.; Szczapa, J. Neonatal Screening for Congenital Toxoplasmosis in the Poznań Region of Poland by Analysis of Toxoplasma gondii-Specific IgM Antibodies Eluted from Filter Paper Blood Spots. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2000, 19, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donadono, V.; Saccone, G.; Maruotti, G.M.; Berghella, V.; Migliorini, S.; Esposito, G.; Sirico, A.; Tagliaferri, S.; Ward, A.; Mazzarelli, L.L.; et al. Incidence of Toxoplasmosis in Pregnancy in Campania: A Population-Based Study on Screening, Treatment, and Outcome. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2019, 240, 316–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Billi, P.; Della Strada, M.; Pierro, A.; Semprini, S.; Tommasini, N.; Sambri, V. Three-Year Retrospective Analysis of the Incidence of Toxoplasma gondii Infection in Pregnant Women Living in the Greater Romagna Area (Northeastern Italy). Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2016, 22, e1–e572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bobić, B.; Klun, I.; Nikolić, A.; Vujanić, M.; Zivković, T.; Ivović, V.; Djurković-Djaković, O. Seasonal Variations in Human Toxoplasma Infection in Serbia. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2010, 10, 465–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Logar, J.; Soba, B.; Premru-Srsen, T.; Novak-Antolic, Z. Seasonal Variations in Acute Toxoplasmosis in Pregnant Women in Slovenia. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2005, 11, 852–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flegr, J. Predictors of Toxoplasma gondii Infection in Czech and Slovak Populations: The Possible Role of Cat-Related Injuries and Risky Sexual Behavior in the Parasite Transmission. Epidemiol. Infect. 2017, 145, 1351–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenter, A.M.; Heckeroth, A.R.; Weiss, L.M. Toxoplasma gondii: From Animals to Humans. Int. J. Parasitol. 2000, 30, 1217–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappas, G.; Roussos, N.; Falagas, M.E. Toxoplasmosis Snapshots: Global Status of Toxoplasma gondii Seroprevalence and Implications for Pregnancy and Congenital Toxoplasmosis. Int. J. Parasitol. 2009, 39, 1385–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molan, A.; Nosaka, K.; Hunter, M.; Wang, W. Global Status of Toxoplasma gondii Infection: Systematic Review and Prevalence Snapshots. Trop. Biomed. 2019, 36, 898–925. [Google Scholar]

- Dubey, J.P. Outbreaks of Clinical Toxoplasmosis in Humans: Five Decades of Personal Experience, Perspectives and Lessons Learned. Parasit. Vectors 2021, 14, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, J.L.; Kruszon-Moran, D.; Elder, S.; Rivera, H.N.; Press, C.; Montoya, J.G.; McQuillan, G.M. Toxoplasma gondii Infection in the United States, 2011-2014. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2018, 98, 551–557, Erratum in Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2018, 99, 241–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rostami, A.; Riahi, S.M.; Contopoulos-Ioannidis, D.G.; Gamble, H.R.; Fakhri, Y.; Shiadeh, M.N.; Foroutan, M.; Behniafar, H.; Taghipour, A.; Maldonado, Y.A.; et al. Acute Toxoplasma Infection in Pregnant Women Worldwide: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2019, 13, e0007807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, E.; de Valk, H.; Villena, I.; Le Strat, Y.; Tourdjman, M. National Perinatal Survey Demonstrates a Decreasing Seroprevalence of Toxoplasma gondii Infection among Pregnant Women in France, 1995 to 2016: Impact for Screening Policy. Euro Surveill. 2021, 26, 1900710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petersen, E.; Meroni, V.; Vasconcelos-Santos, D.V.; Mandelbrot, L.; Peyron, F. Congenital Toxoplasmosis: Should We Still Care about Screening? Food Waterborne Parasitol. 2022, 27, e00162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lafferty, K.D. Can the common brain parasite, Toxoplasma gondii, influence human culture? Proc. Biol. Sci. 2006, 273, 2749–2755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flegr, J.; Dama, M. Does the prevalence of latent toxoplasmosis and frequency of Rhesus-negative subjects correlate with the nationwide rate of traffic accidents? Folia Parasitol. 2014, 61, 485–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.D.; Liu, H.H.; Ma, Z.X.; Ma, H.Y.; Li, Z.Y.; Yang, Z.B.; Zhu, X.Q.; Xu, B.; Wei, F.; Liu, Q. Toxoplasma gondii Infection in Immunocompromised Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurt, K.; Kodym, P.; Stejskal, D.; Zikan, M.; Mojhova, M.; Rakovic, J. Toxoplasmosis Impact on Prematurity and Low Birth Weight. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0262593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huertas-López, A.; Cantos-Barreda, A.; Sánchez-Sánchez, R.; Martínez-Carrasco, C.; Ibáñez-López, F.J.; Martínez-Subiela, S.; Cerón, J.J.; Álvarez-García, G. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the validation of serological methods for detecting anti-Toxoplasma gondii antibodies in humans and animals. Vet. Parasitol. 2023; submitted. [Google Scholar]

- Hald, T.; Aspinall, W.; Devleesschauwer, B.; Cooke, R.; Corrigan, T.; Havelaar, A.H.; Gibb, H.J.; Torgerson, P.R.; Kirk, M.D.; Angulo, F.J.; et al. World Health Organization Estimates of the Relative Contributions of Food to the Burden of Disease Due to Selected Foodborne Hazards: A Structured Expert Elicitation. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0145839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meireles, L.R.; Ekman, C.C.; Andrade, H.F., Jr.; Luna, E.J. Human Toxoplasmosis Outbreaks and the Agent Infecting Form. Findings from A Systematic Review. Rev. Inst. Med. Trop. Sao Paulo 2015, 57, 369–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, L.J.; Timperley, A.C.; Wightman, D.; Chatterton, J.M.; Ho-Yen, D.O. Simultaneous Diagnosis of Toxoplasmosis in Goats and Goatowner’s Family. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 1990, 22, 359–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fertig, A.; Selwyn, S.; Tibble, M.J. Tetracycline Treatment in a Food-Borne Outbreak of Toxoplasmosis. Br. Med. J. 1977, 1, 1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Humphreys, H.; Hillary, I.B.; Kiernan, T. Toxoplasmosis: A Family Outbreak. Ir. Med. J. 1986, 79, 191. [Google Scholar]

- Ginsbourger, M.; Guinard, A.; Villena, I.; King, L.A.; El-Eid, N.; Schwoebel, V. Toxi-infection alimentaire collective à Toxoplasma gondii liée à la consommation d’agneau. Aveyron (France), novembre 2010 [Collective Outbreak of Food Poisoning due to Toxoplasma gondii Associated with the Consumption of Lamb Meat, Aveyron (France), November 2010]. Bull. Epidemiol. Hebd. 2012, 16–17, 195–197. [Google Scholar]

- Baril, L.; Ancelle, T.; Goulet, V.; Thulliez, P.; Tirard-Fleury, V.; Carme, B. Risk Factors for Toxoplasma Infection in Pregnancy: A Case-Control Study in France. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 1999, 31, 305–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buffolano, W.; Gilbert, R.E.; Holland, F.J.; Fratta, D.; Palumbo, F.; Ades, A.E. Risk Factors for Recent Toxoplasma Infection in Pregnant Women in Naples. Epidemiol. Infect. 1996, 116, 347–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapperud, G.; Jenum, P.A.; Stray-Pedersen, B.; Melby, K.K.; Eskild, A.; Eng, J. Risk Factors for Toxoplasma gondii Infection in Pregnancy. Results of a Prospective Case-Control Study in Norway. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1996, 144, 405–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, J.L.; Dargelas, V.; Roberts, J.; Press, C.; Remington, J.S.; Montoya, J.G. Risk Factors for Toxoplasma gondii Infection in the United States. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2009, 49, 878–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, K.; Bahia-Oliveira, L.; Dixon, B.; Dumètre, A.; de Wit, L.A.; VanWormer, E.; Villena, I. Environmental transmission of Toxoplasma gondii: Oocysts in water, soil and food. Food Waterborne Parasitol. 2019, 15, e00049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyer, K.M.; Holfels, E.; Roizen, N.; Swisher, C.; Mack, D.; Remington, J.; Withers, S.; Meier, P.; McLeod, R. Toxoplasmosis Study Group: Risk factors for Toxoplasma gondii infection in mothers of infants with congenital toxoplasmosis: Implications for prenatal management and screening. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2005, 192, 564–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hlaváčová, J.; Flegr, J.; Řežábek, K.; Calda, P.; Kaňková, Š. Male-to-Female Presumed Transmission of Toxoplasmosis Between Sexual partners. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2021, 190, 386–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaňková, Š.; Hlaváčová, J.; Flegr, J. Oral sex: A new, and possibly the most dangerous, route of toxoplasmosis transmission. Med. Hypotheses 2020, 141, 109725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, H.; Swart, A.; Bonačić-Marinović, A.A.; van der Giessen, J.W.B.; Opsteegh, M. The Effect of Salting on Toxoplasma gondii Viability Evaluated and Implemented in a Quantitative Risk Assessment of Meat-Borne Human Infection. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2020, 314, 108380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobić, B.; Nikolić, A.; Djurković-Djaković, O. Identifikacija faktora rizika za infekciju parazitom Toxoplasma gondii u Srbiji kao osnov programa prevencije kongenitalne toksoplazmoze [Identification of Risk Factors for Infection with Toxoplasma gondii in Serbia as a Basis of a Program for Prevention of Congenital Toxoplasmosis]. Srp. Arh. Celok. Lek. 2003, 131, 162–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Said, B.; Halsby, K.D.; O’Connor, C.M.; Francis, J.; Hewitt, K.; Verlander, N.Q.; Guy, E.; Morgan, D. Risk Factors for Acute Toxoplasmosis in England and Wales. Epidemiol. Infect. 2017, 145, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Region/Country | Year | Population | Serological Method * | Commercial/In-House | Samples | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (n) | Positive (%) | ||||||

| North | |||||||

| Estonia | 1999–2001 | General population | ELISA | CM | 215 | 118 (54.88) | [23] |

| 2004–2011 | General population | ELISA | CM | 999 | 557 (55.75) | [24] | |

| 2004–2011 | Other | ELISA | CM | 925 | 539 (58.27) | ||

| Finland | 2000–2001 | General population | MEIA, ELISA | CM | 6250 | 1231 (19.69) | [25,26] |

| 2009 | Other | ELFA | CM | 294 | 43 (14.62) | [27] | |

| Iceland | 1999–2001 | General population | ELISA | CM | 440 | 43 (9.77) | [23,28] |

| Ireland | NR | Pregnant women | MAT | In-house | 20,252 | 4991 (24.64) | [29] |

| Norway | 1992–1994 | Pregnant women | ELISA | CM | 29,912 | 2937 (9.81) | [30] |

| 1994–2005 | Other | ELISA | CM | 1073 | 124 (11.55) | [31] | |

| 2000 | Pregnant women | NR | NR | 361 | 43 (11.91) | [32] | |

| 2003 | Other | ELISA | CM | 620 | 50 (8.06) | [33] | |

| 2009 | Pregnant women | MEIA | CM | 206 | 35 (16.99) | [34] | |

| 2010–2011 | Pregnant women | ELISA | CM | 1922 | 179 (9.31) | [35] | |

| Sweden | 1997–1998 | Pregnant women | MEIA | CM | 40,978 | 7390 (18.03) | [36,37] |

| 1999–2001 | General population | ELISA | CM | 361 | 83 (22.99) | [23] | |

| United Kingdom | 1999 | Other | DAT | CM | 425 | 191 (44.94) | [38] |

| 1999–2001 | Pregnant women | MEIA | CM | 1897 | 172 (9.06) | [39] | |

| 2006–2008 | Pregnant women | ELISA | CM | 2610 | 452 (17.31) | [40] | |

| 2006–2009 | Other | ELISA | In-house | 1403 | 185 (13.18) | [41] | |

| 2012–2015 | General population | ELFA | CM | 5787 | 930 (16.07) | [42] | |

| West | |||||||

| Austria | 1995–2012 | Pregnant women | Several | In-house, CM | 10,3316 | 3864 (37.39) | [43] |

| 2000 | Other | IFAT | In-house | 60 | 32 (53.33) | [44] | |

| 2000–2007 | Pregnant women | IFAT | In-house, CM | 63,416 | 20,103 (31.70) | [45] | |

| 2001–2002 | Pregnant women | SF | In-house | 5545 | 1830 (33.00) | [46] | |

| Belgium | 1991–2001 | Pregnant women | NR | NR | 16,541 | 8049 (48.66) | [47] |

| France | 1995 | Pregnant women | NR | NR | 10,839 | 6806 (62.79) | [48] |

| 1995, 2003, 2010 | Other | NR | NR | 42,886 | 19,015 (44.33) | [49] | |

| 1997–2013 | General population | ELISA | CM | 21,480 | 12,914 (60.12) | [50] | |

| 2000 | Other | NR | NR | 262 | 50 (19.08) | [51] | |

| 2004 | Other | ELISA | CM | 273 | 128 (46.88) | [52] | |

| 2008–2009 | General population | Several | CM | 2060 | 1141 (55.38) | [53] | |

| Germany | 2008–2011 | General population | ELFA | CM | 6564 | 3602 (54.87) | [54] |

| 2008–2011 | Pregnant women | ELISA | CM | 5402 | 1856 (34.35) | [55] | |

| Netherlands | 1995–1996 | General population | ELISA | In-house | 7521 | 3046 (40.49) | [56] |

| 2006–2007 | General population | ELISA | In-house | 5541 | 1441 (26.00) | [57] | |

| Switzerland | 1982–1999 | Other | IFAT | CM | 64,622 | 1806 (2.79) | [58] |

| 2000–2010 | Other | ELISA | CM | 54,216 | 749 (1.38) | [59] | |

| East | |||||||

| Czech Republic | 1988–2006 | Other | Several | In-house, CM | 626 | 268 (42.81) | [60] |

| 1988–2012 | Other | MEIA | CM | 1130 | 474 (41.94) | [61] | |

| 2000–2004 | Other | Several | CM | 3250 | 757 (23.29) | [62] | |

| NR | General population | ELISA | CM | 290 | 93 (32.06) | [63] | |

| NR | Pregnant women | NR | NR | 144 | 23 (15.97) | [64] | |

| Other | NR | NR | 144 | 23 (15.97) | |||

| Hungary | 1987–2000 | Pregnant women | Several | In-house, CM | 31,759 | 18,420 (55.99) | [65] |

| Poland | 1991–2000 | General population | Several | In-house, CM | 9661 | 5297 (54.82) | [66] |

| 1996–1999 | Other | MEIA | CM | 985 | 532 (54.01) | [67] | |

| 1998 | Pregnant women | MEIA | CM | 1920 | 837 (43.59) | [68] | |

| 1998–2000 | Other | DAT | CM | 2684 | 19 (0.70) | [69] | |

| 1998–2003 | Pregnant women | Several | CM | 4916 | 2030 (41.29) | [70] | |

| 2000 | Pregnant women | MEIA | CM | 2016 | 722 (35.81) | [71] | |

| 2000–2003 | General population | MEIA | CM | 4682 | 2574 (54.97) | [72] | |

| 2003–2005 | Other | ELISA | CM | 784 | 490 (62.50) | [73] | |

| 2004–2012 | Pregnant women | ELFA | CM | 8281 | 3364 (40.62) | [74] | |

| 2005 | General population | Several | In-house, CM | 991 | 590 (59.53) | [75] | |

| 2007–2010 | Pregnant women | MEIA | CM | 55 | 28 (50.90) | [76] | |

| 2008 | Other | ELFA | CM | 537 | 292 (54.37) | [77] | |

| 2010–2012 | Other | IFAT | In-house | 169 | 93 (55.02) | [78] | |

| 2013–2014 | General population | NR | NR | 664 | 445 (67.01) | [79] | |

| 2013–2014 | Other | NR | NR | 74 | 37 (50.00) | ||

| 2014–2015 | Other | DAT | CM | 148 | 57 (38.51) | [80] | |

| 2015–2016 | Other | NR | NR | 537 | 103 (19.18) | [81] | |

| 2016–2017 | Pregnant women | NR | NR | 628 | 124 (19.74) | [82] | |

| 2017 | Other | ELFA | CM | 373 | 166 (44.50) | [83] | |

| NR | Other | DAT | In-house | 1497 | 864 (57.71) | [84] | |

| NR | General population | DAT | In-house | 61 | 34 (55.73) | [85] | |

| NR | Other | DAT | In-house | 107 | 70 (65.42) | ||

| NR | General population | ELFA | CM | 293 | 186 (63.48) | [86] | |

| NR | Other | IFAT | In-house | 190 | 77 (40.52) | [87] | |

| Romania | 2001–2006 | Pregnant women | ELISA | CM | 248 | 92 (37.09) | [88] |

| 2005–2007 | Pregnant women | ELISA | CM | 510 | 198 (38.82) | [89] | |

| 2007 | General population | Several | CM | 1155 | 687 (59.48) | [90] | |

| 2011 | General population | DAT | CM | 304 | 197 (64.8) | [91] | |

| 2013 | Other | ELISA | CM | 51 | 24 (47.05) | [92] | |

| 2018 | Other | LAT | CM | 441 | 73 (16.55) | [93] | |

| NR | Other | DAT | CM | 184 | 106 (57.60) | [94] | |

| Russia | 1996–2002 | Pregnant women | NR | NR | 87,099 | 45,373 (52.09) | [95] |

| 1997–2006 | General population | Several | CM | 23,024 | 6250 (27.14) | [96] | |

| 2006–2007 | Other | NR | NR | 4155 | 139 (3.34) | [97] | |

| 2012 | Other | CMIA | CM | 77 | 4 (5.19) | [98] | |

| 2013 | General population | ELISA | CM | 181 | 56 (30.93) | [99] | |

| 2015 | General population | ELISA | CM | 1272 | 323 (25.39) | [100] | |

| Slovakia | 2000–2004 | Pregnant women | ELISA | CM | 656 | 145 (22.1) | [101] |

| 2003 | General population | ELISA | CM | 508 | 123 (24.21) | [102] | |

| 2006 | Other | ELISA | CM | 118 | 40 (33.89) | [103] | |

| 2007 | General population | Several | In-house, CM | 1845 | 577 (31.27) | [104] | |

| 2011 | General population | MEIA | CM | 806 | 282 (34.98) | [105] | |

| NR | General population | MEIA | CM | 1536 | 322 (20.96) | [106] | |

| South | |||||||

| Albania | 2004–2005 | Pregnant women | ELFA | CM | 496 | 241 (48.58) | [107] |

| Bosnia and Herzegovina | 2015 | General population | DAT | In-house | 320 | 98 (30.62) | [108] |

| Croatia | 1994–1995 | General population | ELISA | CM | 1109 | 423 (38.14) | [109] |

| 1994–1996 | General population | ELISA | CM | 1464 | 533 (36.4) | [110] | |

| 2000–2001 | General population | MEIA | CM | 219 | 115 (52.51) | [111] | |

| 2000–2001 | Other | MEIA | CM | 166 | 86 (51.80) | ||

| 2005–2009 | Other | ELFA | CM | 502 | 146 (29.08) | [112] | |

| Cyprus | 2009–2011 | Other | ELISA | CM | 1056 | 69 (6.53) | [113] |

| 2009–2014 | Pregnant women | CMIA | CM | 23,076 | 4129 (17.89) | ||

| Greece | 1984, 1994, 2004 | General population | Several | In-house, CM | 2784 | 851 (30.56) | [114] |

| 1985, 1998 | Other | ELISA | CM | 469 | 124 (26.43) | [115] | |

| 1998–2003 | Pregnant women | ELISA | CM | 5532 | 1628 (29.42) | [116] | |

| 1998–2005 | Pregnant women | ELISA | CM | 12,000 | 3540 (29.50) | [117] | |

| Italy | 1996–2000 | Pregnant women | ELISA | CM | 8061 | 2773 (34.40) | [118] |

| 1996–2000 | Other | ELISA | CM | 9730 | 5 (0.05) | ||

| 2001–2012 | Pregnant women | CMIA | CM | 10,232 | 2814 (27.50) | [119] | |

| 2004–2005 | Pregnant women | ELISA | CM | 3426 | 737 (21.51) | [120] | |

| 2005–2006 | Pregnant women | ELFA | CM | 1501 | 281 (18.72) | [121] | |

| 2005–2006 | Pregnant women | ELFA | CM | 892 | 319 (35.76) | [122] | |

| 2005–2007 | Pregnant women | ELISA | CM | 2356 | 564 (23.93) | [123] | |

| 2007–2009 | General population | MEIA | CM | 10,352 | 2216 (21.40) | [124] | |

| 2007–2010 | General population | MEIA | CM | 13,177 | 3626 (27.51) | [125] | |

| 2007–2014 | Pregnant women | NR | NR | 38,712 | 9368 (24.19) | [126] | |

| 2009–2018 | Pregnant women | CMIA | CM | 45,492 | 9792 (21.52) | [127] | |

| 2009–2011 | Pregnant women | MEIA | CM | 10,347 | 2308 (22.30) | [128] | |

| 2010–2013 | General population | ELFA | CM | 12,306 | 3476 (28.24) | [129] | |

| 2011–2015 | Other | ELFA | CM | 339 | 89 (26.25) | [130] | |

| 2012 | Pregnant women | NR | NR | 846 | 152 (17.96) | [131] | |

| 2013–2017 | Other | ELISA | CM | 1020 | 169 (16.56) | [132] | |

| North Macedonia | 2004–2005 | Pregnant women | MEIA | CM | 235 | 48 (20.42) | [133] |

| Portugal | 2000–2015 | Pregnant women | NR | NR | 4060 | 1055 (25.98) | [134] |

| 2001–2002, 2013 | General population | Several | CM | 3097 | 913 (29.48) | [135] | |

| 2004–2009 | Pregnant women | NR | NR | 3126 | 804 (25.71) | [136] | |

| 2009–2010 | Other | CMIA | CM | 401 | 98 (24.43) | [137] | |

| 2010–2011 | Pregnant women | DAT | CM | 155 | 34 (21.93) | [138] | |

| Serbia | 2001–2005 | Other | DAT | In-house | 765 | 249 (32.54) | [139] |

| 2005 | Pregnant women | MEIA | CM | 334 | 97 (29.04) | [140] | |

| 2011–2012 | Other | ELISA | CM | 79 | 19 (24.05) | [141] | |

| NR | Pregnant women | ELISA | CM | 662 | 180 (27.19) | [142] | |

| Slovenia | 1995–2002 | Other | IFAT | In-house | 413 | 236 (57.14) | [143] |

| 1996–1999 | Pregnant women | IFAT | In-house | 21,270 | 7151 (33.62) | [144] | |

| Spain | 1987–2001 | Pregnant women | MEIA | CM | 2796 | 19 (0.67) | [145] |

| 1992–1999 | Other | ELFA | CM | 7090 | 3009 (42.44) | [146] | |

| 1992–2008 | Pregnant women | MEIA | CM | 47,635 | 15,196 (31.90) | [147] | |

| 1999–2000 | Other | Several | CM | 157 | 56 (35.66) | [148] | |

| 1999 | Pregnant women | NR | NR | 16,362 | 4687 (28.64) | [149] | |

| 2001 | Pregnant women | MEIA | CM | 2929 | 552 (18.84) | [150] | |

| 2002–2003 | General population | MEIA | CM | 2660 | 935 (35.15) | [151] | |

| 2006 | Pregnant women | ELISA | CM | 699 | 183 (26.18) | [152] | |

| 2006 | Pregnant women | MEIA | CM | 2623 | 550 (20.96) | [153] | |

| 2006–2010 | Pregnant women | ELISA | CM | 2933 | 798 (27.20) | [154] | |

| 2007–2008 | Pregnant women | ELISA | CM | 3541 | 602 (17.00) | [155] | |

| 2007–2008 | Pregnant women | MEIA | CM | 1427 | 433 (30.34) | [156] | |

| 2007–2010 | Pregnant women | ELISA | CM | 8012 | 1874 (23.38) | [157] | |

| Factor | No. of Studies Included | Pooled Seroprevalence (95% CI) | Heterogeneity Test | Egger’s Test | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I2 (%) | Q (X2) | Q/df | Q-p (p) | t | p | |||

| Area | ||||||||

| North | 19 | 20.1 (16.8–23.5) | 99.6 | 4261.17 | 19 | <0.001 | 1.14 | 0.267 |

| West | 17 | 38.5 (29.7–47.2) | 100.0 | 1.7 × 105 | 17 | <0.001 | 4.11 | 0.001 |

| East | 47 | 39.7 (32.1–47.2) | 99.9 | 77,136.83 | 46 | <0.001 | 1.18 | 0.243 |

| South | 51 | 27.5 (24.4–30.7) | 99.8 | 27,079.87 | 50 | <0.001 | 2.71 | 0.009 |

| Population type | ||||||||

| General | 38 | 38.6 (33.7–43.6) | 99.8 | 17,521.25 | 37 | <0.001 | 0.79 | 0.432 |

| Pregnant women | 58 | 28.3 (24.2–32.4) | 99.9 | 98,992.78 | 57 | <0.001 | 0.50 | 0.619 |

| Other | 47 | 31.1 (29.0–33.1) | 99.9 | 53,155.52 | 46 | <0.001 | 4.70 | <0.001 |

| Diagnostic method | ||||||||

| Commercial | 101 | 30.2 (28.1–32.3) | 99.9 | 1.8 × 105 | 100 | <0.001 | 9.66 | <0.001 |

| In-house | 15 | 40.1 (35.4–44.8) | 99.3 | 1930.18 | 14 | <0.001 | 1.49 | 0.161 |

| Both | 8 | 43.2 (35.4–51.0) | 99.9 | 7675.92 | 7 | <0.001 | 0.71 | 0.507 |

| Overall | 134 | 32.1 (29.0–35.2) | 100.0 | 3.5 × 105 | 135 | <0.001 | 6.14 | <0.001 |

| Region/Country | Year | Population | Serological Method * | Commercial/In-House | Samples | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (n) | Positive (%) | ||||||

| North | |||||||

| Denmark | 1999–2002 | Newborns | ISAGA | CM | 262,912 | 96 (0.04) | [158] |

| 1999–2007 | Newborns | ISAGA | CM | 547,820 | 100 (0.02) | [159] | |

| Norway | 1992–1994 | Pregnant women | ELISA | CM | 35,940 | 47 (0.13) | [30] |

| Sweden | 1997–1998 | Newborns | ISAGA, ELISA | CM | 40,978 | 45 (0.11) | [160] |

| 1997–1998 | Newborns | MEIA | CM | 40,978 | 3 (0.01) | [37] | |

| United Kingdom | 1999–2001 | Pregnant women | MEIA | CM | 1897 | 12 (0.63) | [39] |

| West | |||||||

| Austria | 1995–2012 | Pregnant women | ELFA, MEIA | CM | 103,316 | 878 (0.85) | [43] |

| 2000–2005 | Pregnant women | ELFA | CM | 51,754 | 51 (0.10) | [161] | |

| 2000–2007 | Pregnant women | ELFA | CM | 63,416 | 66 (0.10) | [45] | |

| 2001–2002 | Parturient women | NR | - | 5545 | 7 (0.13) | [46] | |

| Belgium | 1991–2001 | Pregnant women | NR | - | 16,541 | 8 (0.05) | [47] |

| France | 2004 | General population | ELISA | CM | 273 | 0 (0.00) | [52] |

| Germany | 2008–2011 | Pregnant women | ELISA | CM | 4011 | 17 (0.42) | [55] |

| Netherlands | 2006 | Newborns | ISAGA | CM | 10,008 | 18 (0.18) | [162] |

| Switzerland | 1986–1999 | Women giving birth | ELFA | CM | 64,622 | 107 (0.16) | [58] |

| 2000–2015 | Women giving birth | ELISA, MEIA | CM | 54,216 | 51 (0.09) | [59] | |

| East | |||||||

| Czech Republic | 1988–2006 | Other (HIV+ patients) | ELISA | CM | 626 | 5 (8.06) | [60] |

| 2000–2004 | Other | CFT, ELISA | CM | 3250 | 1 (0.03) | [62] | |

| Hungary | 1987–2000 | Pregnant women | ELISA | CM | 31,759 | 20 (0.06) | [65] |

| Poland | 1996–1998 | Newborns | ELFA, ELISA | CM | 27,516 | 13 (0.05) | [163] |

| 1996–1999 | Women of childbearing age | MEIA | CM | 985 | 9 (0.91) | [67] | |

| 1998–2000 | Newborns | ELISA | CM | 2684 | 15 (0.56) | [69] | |

| 1998 | Pregnant women | MEIA | CM | 1920 | 27 (1.41) | [68] | |

| 1998–2003 | Pregnant women | ELISA | CM | 4916 | 244 (4.96) | [70] | |

| 1999–2000-2003 | General population | MEIA | CM | 4594 | 196 (4.27) | [72] | |

| 2000 | Pregnant women | ELFA | CM | 2016 | 5 (0.25) | [71] | |

| 2003–2005 | General population | MEIA | CM | 784 | 18 (2.29) | [73] | |

| 2004–2012 | Pregnant women | ELFA | CM | 8281 | 803 (9.70) | [74] | |

| 2007–2010 | Pregnant women | MEIA | CM | 55 | 18 (32.73) | [76] | |

| 2008 | General population | ELFA | CM | 537 | 6 (1.12) | [77] | |

| 2015–2016 | Other (Transplant recipients) | NR | - | 292 | 3 (1.03) | [81] | |

| 2016–2017 | Pregnant women | NR | - | 628 | 2 (0.32) | [82] | |

| 2017 | Other (Veterinarians) | ELFA | CM | 373 | 8 (2.14) | [83] | |

| NR | Other | ISAGA | CM | 1497 | 3 (0.20) | [84] | |

| NR | Other | ELFA | CM | 107 | 3 (2.80) | [85] | |

| NR | General population | ELFA | CM | 61 | 0 (0.00) | [85] | |

| NR | General population | ELFA | CM | 293 | 5 (1.71) | [86] | |

| NR | Children (8–16 yrs) | ELISA | CM | 190 | 3 (1.57) | [87] | |

| Romania | 2001–2006 | Pregnant women | ELISA | CM | 248 | 4 (1.61) | [88] |

| 2005–2007 | Pregnant women | ELISA | CM | 510 | 46 (9.02) | [89] | |

| 2007 | General population | ELISA, MEIA | CM | 1155 | 1 (0.09) | [90] | |

| 2013 | Other (Hematological malignancies) | ELISA | CM | 51 | 0 (0.00) | [92] | |

| Russia | 1996–2002 | Pregnant women | NR | - | 87,099 | 1707 (1.96) | [95] |

| 2012 | General population | MEIA | CM | 77 | 0 (0.00) | [98] | |

| Slovakia | 2000–2004 | Pregnant women | MEIA | CM | 656 | 3 (0.46) | [101] |

| 2003 | General population | MEIA | CM | 508 | 0 (0.00) | [102] | |

| 2007 | General population | MEIA | CM | 1845 | 9 (0.49) | [104] | |

| South | |||||||

| Albania | 2004–2005 | Pregnant women | ELFA | CM | 496 | 3 (0.60) | [107] |

| Croatia | 2000–2001 | General population | MEIA | CM | 219 | 2 (0.91) | [111] |

| 2000–2001 | Other (HIV+ patients) | MEIA | CM | 166 | 2 (1.20) | [111] | |

| 2005–2009 | Women of childbearing age | ELFA | CM | 502 | 12 (2,39) | [112] | |

| Cyprus | 2008–2011 | High school females (16–18 yrs) | ELISA | CM | 1056 | 10 (0.95) | [113] |

| 2009–2011 | Pregnant women | ELISA | CM | 17,631 | 107 (0.60) | ||

| Greece | 1984–2004 | General population | MEIA | CM | 2784 | 42 (1.51) | [114] |

| 1998–2003 | Pregnant women | ELISA | CM | 5532 | 185 (3.34) | [116] | |

| 1998–2005 | Pregnant women | ELISA | CM | 12,000 | 396 (3.30) | [117] | |

| Italy | 1996–2000 | Pregnant women | MEIA | CM | 8061 | 188 (2.33) | [118] |

| 2001–2012 | Pregnant women | CMIA | CM | 10,085 | 9 (0.09) | [119] | |

| 2001–2012 | Newborns | NR | - | 738,588 | 1159 (0.16) | [164] | |

| 2004–2005 | Pregnant women | ELFA, ELISA | CM | 3426 | 31 (0.90) | [120] | |

| 2005–2006 | Pregnant women | ELFA | CM | 1501 | 23 (1.53) | [121] | |

| 2005–2007 | Pregnant women | ELISA | CM | 2356 | 113 (4.80) | [123] | |

| 2007–2009 | General population | ELFA | CM | 10,352 | 111 (1.07) | [124] | |

| 2007–2010 | General population | MEIA | CM | 13,177 | 217 (1.65) | [125] | |

| 2007–2014 | Women giving birth | NR | - | 38,712 | 110 (0.28) | [126] | |

| 2009–2011 | Pregnant women | ELISA | CM | 10,347 | 80 (0.77) | [128] | |

| 2009–2018 | Women giving birth | CMIA | CM | 45,492 | 123 (0.27) | [127] | |

| 2010–2013 | General population | ELFA | CM | 12,306 | 164 (1.33) | [129] | |

| 2011–2015 | Pediatric patients | ISAGA, MEIA | CM | 187 | 4 (2.14) | [130] | |

| 2012 | Pregnant women | NR | - | 846 | 3 (0.35) | [131] | |

| 2012–2014 | Pregnant women | CMIA, ELFA | CM | 36,877 | 156 (0.42) | [165] | |

| NR | Pregnant women | NR | - | 892 | 7 (0.78) | [122] | |

| Portugal | 2000–2015 | Newborns | NR | - | 39,585 | 22 (0.05) | [134] |

| 2004–2009 | Pregnant women | NR | - | 3126 | 5 (0.16) | [136] | |

| 2009–2010 | Women of childbearing age | CMIA | CM | 401 | 4 (1.00) | [137] | |

| 2010–2011 | Pregnant women | DAT | CM | 155 | 17 (10.97) | [138] | |

| Serbia | 2001–2005 | Women of childbearing age | ELISA, ISAGA | CM | 765 | 53 (6.93) | [139] |

| 2004–2008 | General population | ISAGA | CM | 1106 | 77 (6.96) | [166] | |

| 2005 | Pregnant women | MEIA | CM | 334 | 4 (1.20) | [140] | |

| 2011–2012 | Women of childbearing age | ELISA | CM | 79 | 9 (11.39) | [141] | |

| NR | Pregnant women | ELISA | CM | 662 | 13 (1.96) | [142] | |

| Slovenia | 1995–2002 | Other (Ocular disease patients) | ELISA | CM | 413 | 18 (4.36) | [143] |

| 1996–1999 | Pregnant women | ELISA | CM | 21,270 | 132 (0.62) | [144] | |

| 1999–2004 | Pregnant women | ELFA | CM | 40,081 | 153 (0.38) | [167] | |

| Spain | 1987–2001 | Pregnant women | ELISA, MEIA | CM | 2796 | 19 (2.40) | [145] |

| 1992–2008 | Pregnant women | ISAGA, MEIA | CM | 47,635 | 24 (0.05) | [147] | |

| 1999 | Pregnant women | NR | - | 16,362 | 106 (0.65) | [149] | |

| 1999–2000 | Other (HIV+ patients) | MEIA | CM | 157 | 1 (1.75) | [148] | |

| 2001 | Pregnant women | MEIA | CM | 2929 | 24 (0.82) | [150] | |

| 2006 | Pregnant women | MEIA | CM | 2416 | 8 (0.33) | [153] | |

| 2007–2008 | Pregnant women | MEIA | CM | 1427 | 12 (0.84) | [156] | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Calero-Bernal, R.; Gennari, S.M.; Cano, S.; Salas-Fajardo, M.Y.; Ríos, A.; Álvarez-García, G.; Ortega-Mora, L.M. Anti-Toxoplasma gondii Antibodies in European Residents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Studies Published between 2000 and 2020. Pathogens 2023, 12, 1430. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens12121430

Calero-Bernal R, Gennari SM, Cano S, Salas-Fajardo MY, Ríos A, Álvarez-García G, Ortega-Mora LM. Anti-Toxoplasma gondii Antibodies in European Residents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Studies Published between 2000 and 2020. Pathogens. 2023; 12(12):1430. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens12121430

Chicago/Turabian StyleCalero-Bernal, Rafael, Solange María Gennari, Santiago Cano, Martha Ynés Salas-Fajardo, Arantxa Ríos, Gema Álvarez-García, and Luis Miguel Ortega-Mora. 2023. "Anti-Toxoplasma gondii Antibodies in European Residents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Studies Published between 2000 and 2020" Pathogens 12, no. 12: 1430. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens12121430