1. Introduction

The liberal arts have long been the shibboleth of the privileged and a tool for exclusion—a fact that will be of no surprise to anyone with even an undergraduate-level familiarity with Bourdieu’s writings on

habitus (

Bourdieu 1977). This exclusion obviously is in conflict with the goals of “equity”, “diversity”, and “inclusion” that the modern academy purports to uphold

1. This contradiction, in turn, gives us a powerful argument for making deep and meaningful education in history, literature, languages, music, and other fields a universal part of the college experience. Yet, in a time of neoliberal governance of higher education, we see the reverse: the liberal arts are being defunded and marginalized. Institutions’ stated values are thus in conflict with their actions. My aim in this essay is to show how the cognitive dissonance inevitably produced by these two facts can and should be used as an argument for reinvestment in the liberal arts. As the late Derrick Bell pointed out (

Bell 1980), advances in social justice come only when they serve the needs of the dominant white group. I wish to show that reinvestment in the liberal arts in the name of racial justice is in the interest of those who hold power. The alternative is nothing more than blatant hypocrisy that delegitimizes the power structure and, ultimately, as a result of activism, may result in remedies such as lawsuits or even re-regulation that will put federal funds or even accreditation at risk. Reinvestment in the liberal arts is thus, I argue, in the interest of academic leadership and boards of trustees.

I would additionally argue that such reinvestment must reach far beyond the top-tier schools where the liberal arts are most securely established. As I was once told by the president of a private, non-selective college whose undergraduate population was composed primarily of first-generation students of color coming from underserved school districts and families living below the poverty line, the school’s “curriculum has to be very practical, and it really has to focus on those kids who are trying to make a better life for themselves. We don’t need to be designing our English classes so that they can analyze and take apart the Brontës and Louisa May Alcott and things; we need to have English courses that make kids read better and write better”. I could not disagree more: Such a statement not only implies that exposure to classic literature and attaining college-level literacy are fundamentally incompatible; it also seems to me to be profoundly classist and racist, implying that “Brontës and Louisa May Alcott and things” (let alone my own field of medieval studies) are not for the underprepared, low-income students of color at this school. Indeed, for reasons I will discuss below, they may not be—but many would dispute the entire way in which the question is posed, as it is redolent of a worldview where “works of literary value” is synonymous with “old and white” and literary analysis is a leisure activity for the elites that is not in any way “practical”. Further, it paternalistically implies that these students are not and will never be capable of analytical work—which belies the fact that liberal arts education changes how everyone engages in life as a whole, regardless of their specific situation such as the socioeconomic status of their family of origin or access to schooling.

My sole aim in this essay is to show the necessity of reinvesting in the liberal arts to those who make decisions, such as the college president I just mentioned, by pointing out the hypocrisy inherent in the discrepancy between their stated values and their actions. It is a persuasive essay, written in an editorial vein, and fueled by anger and grief that the private, non-selective college headed by the aforesaid president fired both tenured professors in the history department just before the fall 2020 semester began, eliminated the major, and is hiring adjuncts to teach their remaining sections (including the school’s only classes in African-American studies) for $2300 per 3-credit class per semester.

I am therefore going to ask the reader’s indulgence in one thing: I am going take the postulates advanced by critical race theorists—“Crits”—as true. These claims include the idea that racism is not aberrant, but normal and embedded within society; and that legal, scholarly, and social norms are, like the idea of race itself, social products that need to be critically analyzed and dismantled in order to create a moral, fair, just, and equitable world. I am not making any claims herein as to the epistemological truth of Critical Race Theory (CRT), nor am I aiming to explain its ever-evolving literature in any systemic way

2. Rather, I will merely assert that CRT is ascendant within the academy and that it is particularly socially relevant in the wake of the Black Lives Matter movement as it has played out in 2020. Arguing from a position of

realpolitik (that is, practical application of the levers of power based on empirical study), I believe that all involved will admit that the

idea that we must actively confront and dismantle racism—in other words, the idea of antiracism as articulated by such thought leaders as Ibram X Kendi (

Kendi 2019)—has been rapidly gaining ground in American academia. At the risk of committing the bandwagon fallacy, I therefore ask the reader to accept Crit ideas as accurately describing the world we live in and a necessary course of action.

In this vein, I will point out that this reinvestment in the liberal arts that I am calling for must also be a reevaluation. Many proponents of CRT hold that we must teach the liberal arts in new ways and rewrite the “canon” to not only include new and diverse perspectives, but also incorporate and interrogate the power dynamics and power systems related to those diverse perspectives. CRT holds that if we are to create a more truly equal and just world, then we must not stop at empowering students hailing from historically excluded communities to share their own narratives, nor should we merely continue the well-established trend of including the voices of women and people of color in the curriculum (see

Parker 2003) for a brief history). Rather, all fields must be rallied to question the elitist, Eurocentric past, and all students should confront these questions in their classes. As Medievalists of Color put it in their Collective Statement of 2017, “if we find that the scholarly paradigms of critical race and ethnic studies, postcolonialism, and decolonization do not speak fully to the historical moments we study, we are obligated to enter, and even expand, the conversations they engender”.

This sensibility puts a codicil on W. E. B. Du Bois’s famous passage from

The Souls of Black Folk (

Du Bois 1903): “I sit with Shakespeare, and he winces not. Across the color line I move arm and arm with Balzac and Dumas, where smiling men and welcoming women glide in gilded halls…. I summon Aristotle and Aurelius and what soul I will, and they come all graciously with no scorn nor condescension. So, wed with Truth, I dwell above the veil…” Du Bois was writing in opposition to Booker T. Washington’s “Atlanta Compromise” that asserted that education for African-Americans should be vocational and asserting the fundamental equality of the Black intellect. History has taken Du Bois’s side in this debate. But “truth”, to the CRT eye, is socially contingent: “If we wish medieval studies to engage meaningfully in the modern world of which it is a product, and in which it is an agent, then medievalists must also rigorously engage with the fields that examine the ideologies and distributions of power that define the modern world” (

Medievalists of Color 2017). We must ask if Du Bois read Shakespeare in the same way that his contemporary, Harvard professor of English Bliss Perry, did. If we are to “sit with Shakespeare”, we must, as every generation does, ask new questions of him: the Otherness of Othello; the monstrosity of Shylock. If we introduce Homer, Chaucer, or Shakespeare to undergraduates—or for that matter Murasaki Shikibu or the

Rigveda—then maybe we should do so in dialogue with more modern authors and critical sources. It often seems that the study of other European writers—medieval German poets, for instance—is only useful to this epistemology insofar as these sources can be read with a critical eye to reveal, say, the origins of Western racism or the construction of “whiteness”. To be sure, as other essays in this volume make clear, such a study is a good in its own right—but it does not generate the sorts of useful truths that are central to the strategy I put forth in this essay, and so I will be leaving this question aside.

In my own field, Crit ideas have been most advanced by the Medievalists of Color collective, the associated

In the Middle blog, and their allies

3. For instance, Dorothy Kim, in her widely read and widely debated 2017 essay “Teaching Medieval Studies in a Time of White Supremacy”, puts forward our mutual field as one that upholds the beliefs and practices of a society that systemically excludes people of color (

Kim 2017). To counter this white supremacy, Kim exhorts readers to activism: “[c]hoose a side” because “[d]oing nothing is choosing a side. Denial is choosing a side. Using the racist dog whistle of ‘we must listen to both sides’ is choosing a side”. Kim therefore directs the reader to engage in “overt signaling of how you are not a white supremacist and how your medieval studies is one that does not uphold white supremacy”.

The assumptions underlying Kim’s deployment of “white supremacy” were more fully articulated by Carol Symes on the American Historical Association blog in a post of 2 November 2017 (

Symes 2017). Symes addressed “white supremacism’s (latent or blatant) influence in the shaping of various disciplines, including medieval studies” and stated that:

The informed study of “what happened” during those eras (variously defined) is therefore inextricable from the ongoing interrogation of when, how, and why these categories were invented. In fact, “medieval” Europe was co-created in tandem with white supremacism, the “scientific” racialization of slavery, and modern European imperialism. Moreover, previous generations of medievalists, often working in the service of these modern projects, have not only shaped the terms of our engagement with historical sources, their work has shaped the sources we have. The medieval archive has been (and continues to be) selected, edited, translated, censored, packaged, and destroyed by forces beyond the control of the people who generated the components of that archive. There is no way to do medieval history responsibly without engaging its modern and postmodern entanglements.

I am arguing that the study of the liberal arts is worthy of reinvestment by pointing out that such “engaging… modern and postmodern entanglements” is necessary to Crit efforts to dismantle the white-supremacist regime as embodied in the modern American college curriculum.

4 The statements and assumptions such as those of the aforesaid college president would most certainly be considered symptomatic of this regime, and are therefore unacceptable. Furthermore, I am arguing that deploying Crit arguments in such a manner is of utility to the modern university, and beneficial to imperiled humanities departments in making an argument for their continued survival in a time of tightened belts and increased neoliberal governance (

Altbach et al. 2011).

5I also maintain that a study of Crit thought can reinvigorate a field such as medieval studies by suggesting new approaches and avenues of research. As I said in my previous essay “Words and Swords: A Samizdat on Medieval Military History and the Decolonization of the Academy” (

Mondschein 2018), “an “intersectional” perspective could provide a useful tool for us to explore some of the core questions in our field in new and interesting ways”. Speaking specifically of medieval military history, I continued:

If we are to understand imperialism and exploitation of subject peoples, and the ideology that justifies it, we can not neglect the Norman conquest of Wales and Ireland or the subjection of Livonia any more than we can neglect the Spanish conquest of the Americas or the Belgian Congo, as they are all linked in a long history of thought, institutions, and ideas. Just as historians of the latter subjects should appreciate the importance of our work for their areas of concern, so those of us working on the former topics need to take account of the new scholarship on modern imperialism, which can provide us with invaluable perspectives, questions, methodological examples, and theoretical frameworks…. it is but a small step to include a postcolonial approach that looks at the effects of these interactions on both colonizers and colonized. Asking questions such as “how is a Welsh archer fighting for the English crown like, or unlike, a Sepoy?” can only enrich our understanding of our subject of study.

The same can hold true for the study of medieval trade, institutions, or literary production. Let us not, therefore, see CRT as a foreign insertion into our fields of study, but rather as new roots onto which we can graft old vines and which will not only reinvigorate the fruit thereof, but also, incidentally, save us from systemic rot.

2. Liberal Arts in the United States

Let us look at the Crit supposition, as expressed by Symes’s essay, that we cannot separate knowledge from the system in which such knowledge is generated. We must therefore understand that systemic inequality in American higher education is rooted not only in a systemically racist society, but in the unique nature of the system. This differs from that of most other nations in several important ways—namely, American higher education’s insistence on a broad course of study; the historical conditions of its development; the idea that, while students must pay for their own education, a college degree is necessary for all; and its self-appointed activist role in society.

Regarding the first, an American college degree requires a certain distribution of general-education credits. The United States does not have polytechnics or vocational colleges; rather, literature majors must be familiar with the scientific method; scientists must take courses in writing. Regarding the second, American schools also retain their own unique sociological environment, including a longstanding distinction between the liberal arts colleges, which helped to frame a northeastern elite, and the religious- and state-sponsored land grant universities and (former) normal schools and polytechnics of the masses (

Mondschein 2010;

Geiger 2014). To these, I must also add historically Black colleges and universities, which have their own unique history. At the bottom rung, of course, are the non-selective schools like the one headed by our aforesaid college president, where most students are enrolled in vocationally-oriented majors and are disinterested in their gen-eds, and many, or even most, core courses are taught by over-stretched, under-paid adjuncts. The rise of such institutions was aided in the past 70 years by the ubiquity of higher education. After World War II, the GI Bill, which educated 2 million veterans, led to the vast expansion of the American higher education system. In 1930, there were only 122,000 college graduates in the US; in 1950, there were 432,000. The Baby Boomer generation followed their parents: there were 2.5 million college students enrolled in 1955, 3.6 million in 1960, and over 6 million in 1966. This led to a profound shift in the nature of higher education. No longer something only for the leaders of society, a college degree (and, increasingly, a postgraduate degree) was seen as the prerequisite for a middle-class lifestyle.

In conjunction with this, the Higher Education Act of 1965 and the Higher Education Amendments of 1972, which established a national system of direct loans and grants, enabled not only the expansion of large state universities, but the flourishing of the aforesaid small, non-selective colleges. At the institution in question, for instance, 60% of students receive Pell grants. I should note here that with the increased expense of running a college coupled with competition for a declining number of potential students, many of these schools are facing existential financial threats and have been forced both to become even less selective in whom they admit and to cut corners in other ways. The aforesaid institution, for instance, boasts an 18:1 student/faculty ratio that it achieves only by employing an army of adjuncts whom it pays the aforesaid $2300 per course. (This is at a school that charges almost $40,000 a year for non-discounted tuition, room, and board, which necessitates that many, if not most, students take out loans to pay for their education.)

Simultaneously with the expansion of higher education in America came a new role for the university—that of the left-wing social critic and even incubator of countercultural sentiment. Schools from Berkeley to Chicago to New York became hotbeds of protest against Jim Crow, the Cold War, and the overall political milieu of the World War II generation. No aspect of higher education has remained untouched by this tendency. Title IX coordinators and Diversity and Inclusion officers have long been mandatory staff positions and, more recently, universities and their culture have been profoundly influenced by the #metoo and Black Lives Matter movements. Medieval studies, for instance, has participated in this as well, such as the Marxist turn of the 1960s, the women’s and LGBTQ history that came to the fore in the 1970s and 1980s, and, more recently, the adoption of the “global Middle Ages” and CRT. This does not mean, of course, that there has been universally greater equity in professional ranks; in particular, the progress of African-Americans in securing tenure-track jobs has been called “snail-like” (

Journal of Black Higher Education 2008–2009). Rather, academics have called for change while largely leaving existing power structures intact—which is to say largely white and middle class

6.

Further, because college tuition in America is paid for privately (even the aforesaid Pell grants take the form of aid to individuals), there has been, simultaneously with the rise of the university-as-thought incubator, a call for tangible returns on investment. This renewed emphasis on accountability and fiscal results in American education, coupled with the traditional vocational/liberal-arts divide, has similarly renewed the debate over the value of the humanities. Traditionally, it was the elite who studied Greek, Latin, history, and other “arts” subjects, and the sub-elites who received vocational training. A passing familiarity with Homer, Voltaire, and Monteverdi was part of the elite habitus, a cultural symbol, like a custom-tailored suit or the Grand Tour, that marked one as a member of the ruling class—thus, the general-education requirements. Land-grant universities, as part of their imperative, sought to bring this knowledge to the masses even as most courses were taken outside of the humanities. In the immediate post-World War II era, the gap between the upper middle class and the upwardly striving middle class briefly lessened. Newly prosperous parents bought pianos, sent their college-age children to Europe with travelers’ checks and Eurorail passes, and bought season tickets to the opera. High culture had no longer become the exclusive province of the elite.

However, in an era of increased income inequality, how does understanding Shakespeare help today’s student become a better worker? Why does a primary school teacher need to take World Civilizations? Why do future healthcare workers need to be able to give public presentations? Effectively, what those such as the college president I interviewed are saying is that those who are destined for non-elite schools have no business being educated the “finer things”, and, indeed, it is foolish to become interested in them. High culture is returning to the prewar state of being the exclusive province of the well-heeled, not for upwardly-mobile strivers, who will never learn the idioms of the true masters of the universe, and certainly not for those from disadvantaged backgrounds. For these people, college is not for personal development, but for learning a trade. As for medieval studies, the Middle Ages may be fine when it comes to mass-culture entertainment that portrays a grimdark past from which enlightened modernity arose—think Game of Thrones—but why would anyone ever want to study that professionally, when one can find out as much “accurate” medieval history as one likes online, from video games, or from medievalist hobby groups such as the Society for Creative Anachronism?

With the contraction of higher education due to falling birthrates and market saturation; the financial downturn of 2008 and 2009; and now with the COVID-19 crisis, even elite education has become marketed as career-oriented. However, this is only an acceleration of a trend that has been present since the 1980s. An excellent early case study of these tendencies is Elizabeth Coleman’s tenure as President of Bennington College. Her actions, deplored at the time, now seem prescient. Bennington was formerly known as a haven for the artistically inclined scions of the East Coast elite and had a reputation for producing well-known figures in writing, music, and other cultural endeavors. In the postwar period, it became the province of newly affluent Jewish families. There was no formal tenure system in place, but rather a system of “presumptive tenure”; many of the professors lived in campus housing, and it can be truthfully said that the tiny college in the middle of the Vermont woods was the center of their intellectual, social, and professional lives.

Coleman was hired by the College’s Board of Directors in 1987, and was widely, and justly, credited with saving the school from financial disaster. However, as part of this, the board passed a “Plan for Changes in Educational Policy and Reorganization of Instructional Resources and Priorities” in April 1994 that included the elimination of entire departments (which, in some cases, consisted of a single faculty member), the reorganization of the school in favor of a “practitioner-teacher” model, and the elimination of “presumptive tenure” in favor of pro-term contracts (

American Association of University Professors 1998a,

1998b). The ostensible reason was to make Bennington more competitive in the marketplace, but the effect was to eliminate much of what made the school unique—including many of the liberal arts and social sciences faculty. Language and music instruction were outsourced to the local “community”. (Remember this was in rural Vermont, which limits available resources). Dance and music teachers were to be professionals whose work was currently being performed; literature faculty was to be active writers instead of scholars of literature; art historians were dismissed in favor of working visual artists. This, needless to say, was unparalleled and went against the entire idea of an independent, professional liberal arts faculty that considers its subject from a scholarly, critical perspective and takes part in communal governance. Rather, it made the professorate dependent on an administration that considers matters primarily from a financial perspective.

Such disinvestment has a profound effect on equity. By deprofessionalizing the professorate, the adjunct system presupposes that those with the luxury of teaching the liberal arts already possess a fair degree of privilege and security and perpetuates race, class, and gender discrimination (

American Association of University Professors 1993;

Coalition on the Academic Workforce 2012;

American Association of Community Colleges 2014;

Bérubé and Ruth 2015). These assumptions are in no way accurate.

Finley (

2009) states that, depending on the field, between 51% and 61% of contingent faculty are women, and that “while the pay gap between men and women in the United States is related in no small part to discrimination, it is also related to the fact that women tend to be employed in areas of the market that pay less than those where more men work”. Fields that employ more contingent faculty tend to also employ more women, making relying on adjunct labor part of the devaluing of women’s work. Further, as

Boris et al. (

2015) put it, “Adjuncts are ‘feminized’ by their position as flexible, low-paid workers, a paradigm designed to cut costs…. work conditions conspire to make them feel isolated. Many teach at multiple institutions to earn a living, never establishing connections within their departments…. Some internalize the lack of respect, choosing not to address their situation head on because it is painful. They fear losing classes”.

The same with race: According to the

U.S. Department of Education (

2019), “Of all full-time faculty in degree-granting postsecondary institutions in fall 2017, 41 percent were White males; 35 percent were White females; 6 percent were Asian/Pacific Islander males; 5 percent were Asian/Pacific Islander females; and 3 percent each were Black males, Black females, Hispanic males, and Hispanic females. Those who were American Indian/Alaska Native and those who were of two or more races each made up 1 percent or less of full-time faculty”.

These two imperatives in higher education—social justice and neoliberalism, certainly polar opposites—are therefore mutually irreconcilable. Besides the fact that we are asking a machine that was designed as a marker of class status to perform a task it was not designed to do—that is, promote equality—to accomplish the aims of social justice requires investment in the very liberal arts that seem pointless to those who think only of market value. Only by thinking critically about our society at large can we begin the vital questioning of values required by the university’s new, self-appointed mandate—dismantling white supremacy and promoting equality. However, this gaze must be inward as well, since in reestablishing the liberal arts curriculum, we must also critically evaluate and even rewrite what purposes the “liberal arts” serve.

3. The Social Purpose of Higher Education

Just as we cannot consider the liberal arts outside of the context of American higher education, we must also consider the liberal arts in the context of society itself. There has been no shortage of ink spilled protesting cutbacks to the liberal arts in higher education; the present volume is but the latest salvo in a long barrage. These responses are usually penned by pundits answering neoliberal critiques by speaking in some version of the critics’ own terminology of economics and seeking to justify traditional humanistic studies according to some notion of abstract value or the Socratic examined life. However, if we look at how universities function in society, another picture emerges.

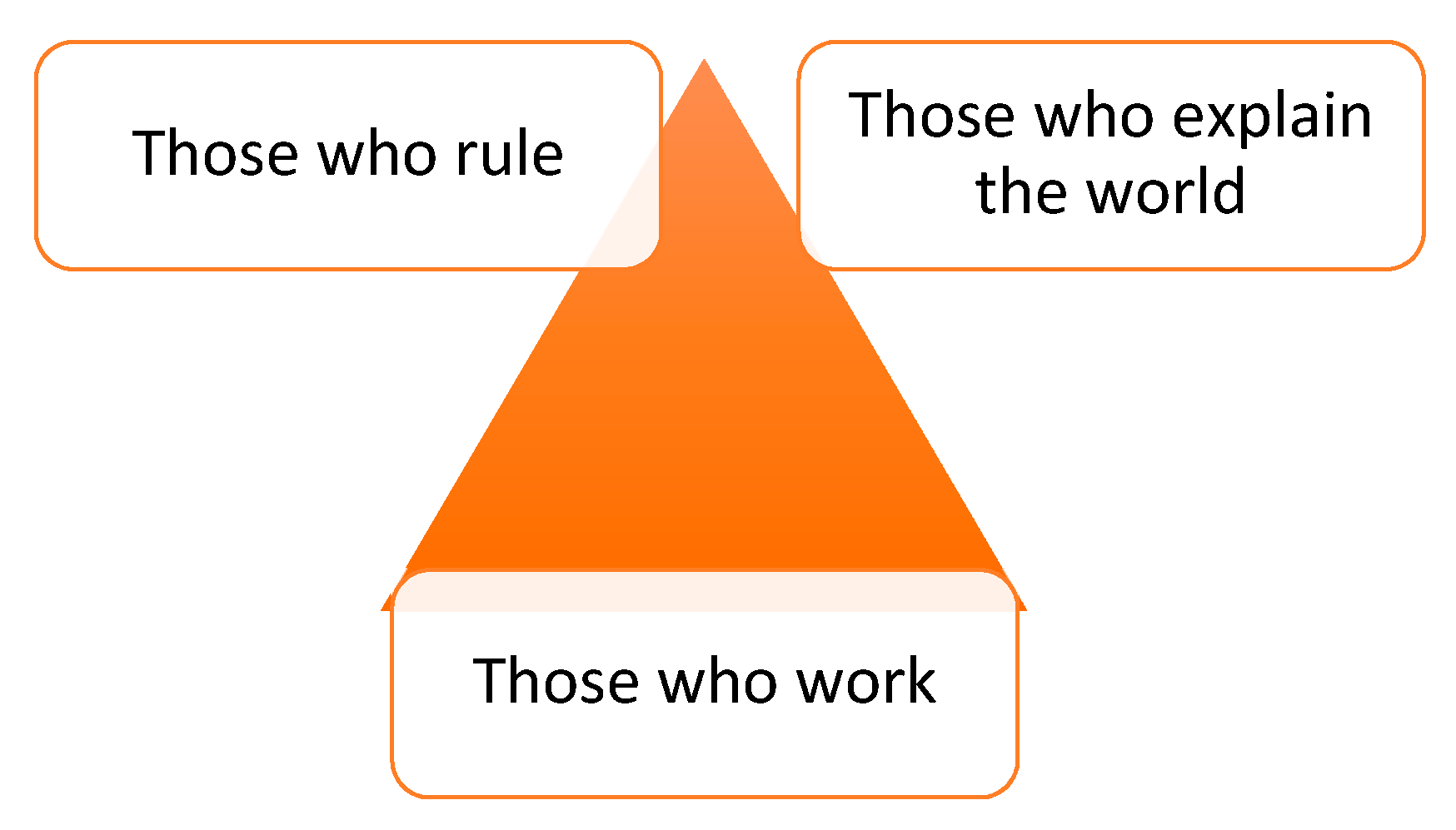

Figure 1 is an image that I draw on the board in the first week or so of all my introductory classes:

Obviously, I have been highly influenced here by any number of Marxist-based historical schools, particularly the annalistes—all ultimately rooted in the “three estate” idea. Despite its European origins, one can make the argument that this system has been inherent to all post-Neolithic societies ever since the peasants gathered around the ziggurat to ask why they had to render tribute to the great King Gilgamesh and the priest descended the steps to tell them it was because the great god Marduk said it must be so. In imperial China, the legitimacy of the imperial power was explained by the official Confucian philosophy. In medieval Europe—in which, of course, the modern university system was birthed—the rulers were the feudal nobility; the workers were, for the most part, the peasants; and those who explained the world were the clergy. Universities, of course, fit into the “clergy” role, and had their origins within the medieval Church.

In early modern Europe, the power structure of society changed, as did scholarship. Copernicus, and, after him, Galileo, overthrew the Ptolemaic cosmos and Aristotelian physics; Hobbes justified absolutist monarchy, and, after him, Locke justified the Glorious Revolution and parliamentary rule; Newton showed how the divine plan for the cosmos could be understood and explained through mathematics. As Peter Gay put it in his landmark

The Enlightenment: An Interpretation (

Gay 1966), modernity came from the idea of a mechanistic universe posited by the ancient Latin poet Lucretius in his

De Re Natura, together with the Newtonian idea of humanity’s ability to know and master these laws. The entire positivist project—that the universe, including human society, functions by knowable laws, and that by mastering these laws, we can perfect the world—followed. The task of achieving the Kingdom of Heaven had been wrested from the hands of the saints and placed in those of the savants.

However, the interpretation of the human world will always follow the dictates of the power structure. Malthus and Ricardo used Smith’s economic theories to explain how it was a net benefit to society to pay the laboring classes below subsistence-level wages. Darwin’s ideas were used in nineteenth-century “scientific” racism to justify slavery and imperialism, explain how the Irish were barely human, and tout the benefits of eugenics. The Soviet Union invested in “scientific Marxism-Leninism” and Lysenko’s genetics for political purposes. Critical Race Theory, such as embodied in Symes’s statement that “[t]he informed study of ‘what happened’... is therefore inextricable from the ongoing interrogation of when, how, and why these categories were invented” both participates in and questions this sentiment.

I would argue that one subtext of the work of the scholar, from the priest of ancient Egypt to the mandarin of imperial China to the modern political scientist or economist, is ultimately to justify a particular distribution of power in a society. In modern America, this function is justified by financial exigency. The humanities neither produce wealth nor wield power, and attempts to justify their existence in the language of neoliberalism are doomed to failure. What we do is give a narrative that implicitly defends the order of things and trains the next generation to continue it—thus, the canon of great white males working in the tradition of Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle, or, since the 1960s, the counterargument critiquing this power structure. In the end, this is the same thing, as it merely rearranges the pieces in the hierarchy rather than upending it entirely. In the end, the hierarchy itself is unchanged. The stories that are useful to us are those that tell narratives that further present-day agendas—to wit, the movements towards both neoliberalism and inclusivity, diversity, and globalism. These mandates have affected even remote provinces such as Medieval Studies, which is, I believe, why attempts to put the Middle Ages on the forefront of the fight against white supremacy have found such fertile ground in medievalist fields. The carrot-and-stick system is the same as it ever has been: create useful truths, and you will be rewarded.

Lest I be accused of undue cynicism by scholars of a more conservative bent, let me be clear that I am not speaking here of the disinterested, scholarly study of ars pro gratia artis that one might see advocated amongst the elder generation of tenured scholars. As the editor pointed out in initial reviews of this essay, “studying Brecht or D. H. Lawrence does not make one a defender of traditional society”. However, again, to one steeped in CRT, there are no disinterested scholars: anyone who is not actively anti-racist, anti-misogynistic, anti-homophobic, anti-transphobic, and anti-imperialist in fact contributes to these epistemes (or more properly, what Bourdieu would call “these doxas”, or common beliefs; it is CRT itself that is the true episteme, or scientific knowledge). The very emphasis on studying Brecht or D. H. Lawrence, or at least on studying them without references to the doxas they support, is itself a symptom of a racist system that one can hardly perceive, just as a fish does not know it is swimming in water. Such Crit beliefs are widespread amongst younger scholars, and no matter whether one agrees or disagrees, there is no doubt that first, these sentiments are useful when applying for a position or persuading an administrator to approve the same; and that, second, they are rapidly becoming the new disciplinary orthodoxy.

The problem is, as I pointed out above, the goals of neoliberalism and social justice are mutually irreconcilable, and we wind up merely paying lip service to the latter while continuing the structures of the former unchanged. We are not dissimilar to an education department simultaneously wrestling with irreconcilable questions of how to improve outcomes in poor districts as measured by the metrics of government-mandated standardized testing even as they deal with profound inequality between students’ socioeconomic situations compared to their more privileged peers. The task is Sisyphean.

The task is additionally complicated by the class structure of academia. Education signifies pedigree and serves as a social network and vetting process, which is why the question of where one went to university is akin to the Homeric question of parentage. For instance, a recent study found that half of history faculty openings went to the graduates of approximately eight schools (

Clauset et al. 2015). Yet, ironically, to be admitted into one of these schools, let alone consider a career in the liberal arts professorate, requires quite a bit of privilege in the first place. CRT most certainly considers issues of class in its theories: The tenets of intersectionalism as expressed by the

Combahee River Collective (

1977), Kimberlé Crenshaw (e.g.,

Crenshaw 1989), Patricia Hill Collins (

Collins 1990) show that one cannot merely consider oppression in light of race; one must also consider factors such as social class and gender. This intersectional perspective is fully present in medieval studies: As the cover of the Volume 10, Issue 3 (September 2019) issue of

postmedieval put it (riffing off of Falvia Dzodan), “my medieval studies will be intersectional, or it will be [useless]”. (The obscenity that properly belongs within the brackets has been removed at request of the editor).

However, what is disturbing to me is, considering that status-conscious nature of academia, the possibility of the radical, hierarchy-upending ideas expressed by Crit writers being weaponized by colleagues against colleagues as a means of gaining resources within a shrinking field, when in fact we should be weaponizing them against the

administration in order to spread the teaching of the liberal arts; admit women, people of color, and other historically excluded groups into a revitalized and financially secure professorate; and to spread the epistemology of CRT to all stakeholders. To be sure, those who manifestly enable racism, bully those with less power, or consort with admitted white supremacists must be “called out”; on the other hand, when dealing with those who, like many of our colleagues, merely express “white fragility” (see

DiAngleo 2018) or who display an imperfect understanding of the tenets of CRT, I would instead urge “calling in”: acting with compassion and patience to ask people who see themselves as allies to act in more thoughtful, less harmful ways. This would, in turn, build a broader coalition between those spreading progressive ideas and those who already have positions of power and/or influence within the field.

Further, if we are truly going to do what Crit writers say we must do, then we must do it in accessible ways that do not replicate previous exclusionary practices to create in-groups and out-groups—not only in the professorate, but among our students and in society at large. For instance, the tenets of CRT should be readily explained in a way that first-year college students freshly arrived from underserved school districts can readily understand. Hiring committees should be given explicit mandates to diversify the professorate. Articles and essays should avoid baroque, “academic” language, and must not be hidden behind paywalls. Perhaps most controversially, I believe that those who hold old-fashioned assumptions cannot be merely “cancelled” (that is, socially excluded and deprived of employment) and left to fester in a corner; rather, we must utilize Bell’s “convergence theory” by “calling them in”, making them see that reading and adopting CRT is in their best interests, recruiting them by explaining why “studying Brecht or D. H. Lawrence” in an unexamined way does, from the CRT perspective, make one a “defender of traditional society”, and thus establishing the cognitive dissonance that leads to self-reflection. (And, needless to say, it is not acceptable to fire the liberal arts professors at a school that serves low-income students, particularly when those professors are the ones who spread a message of social justice).

In whose hands, then, are we placing the power? Who will be in possession of this canon? Is the power of interpreting the humanities only for those few who “make it” to elite schools and land a tenure-track job—those with pedigree, fortunately recognized talent, or just luck? Who is given the power of having their narratives heard? Who gets to teach and interpret “the Brontës and Louisa May Alcott and things”? Better yet, who will teach and interpret Ibram X Kendi, Ta-Nehisi Coates, Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw, or Angela Davis? Who will be the next Ibram X. Kendi, Ta-Nehisi Coates, Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw, or Angela Davis? Critical Race Theory cannot be allowed to become another tool for the ruling class. In other words, we cannot let administrations adopt the language of social justice while doing nothing to create a more empowered and diverse professorate.

One can, for instance, easily see a school dismissing tenured professors on the basis of “financial exigency”; hiring adjuncts of color to cover their classes; paying said adjuncts far less than they paid the full-timers, and then boasting of the “diversity” of its teaching staff. Another way in which systemic racism is perpetuated every day is by failing to post salaries in a transparent fashion. A personal anecdote: When I was contracted as a lecturer in the UMass system to do a teach-out of the remnant students at a newly acquired campus, I asked for the same per-class salary that I had received in the state college system. The chemistry professor, a woman who was born in Africa, asked for and received thousands less. (We were, in fact, both being paid under the contracted rate, and eventually, the union stepped in and demanded we be paid on par with what was legally required, including back pay).

Unless we keep incidents like these from happening then, much as the corporate world has done, we merely pay lip service to diversity and inclusion while not making any real change. Only by educating the broadest number of people the most deeply can we in the broadest, most humanistic way possible, remove “the liberal arts” from the precincts of the privileged and pave the path for a more equal and just world—and we can, in turn, only accomplish this goal by creating a fair and just workplace for the labor of education.

4. Whose Episteme, Then?

The liberal arts, as they have been traditionally constituted, constantly harken back to the past either by studying it or reacting to it. The problem is that, from the perspective of CRT, the past that “the Brontës and Louisa May Alcott” harkens back to is a

white, Eurocentric past, a past in which the voices of people of color were frequently marginalized. To deign Homer and Shakespeare the pinnacle of high culture is to say that the past of white European males is normative for human experience and that today’s elites stand in a tradition of mostly-male writers that goes back to Plato and Aristotle. We have begun including the voices of women in this canon, as our college president’s quote shows, but in groping for “the Brontës and Louisa May Alcott”, he still chose works in which elites can “see themselves”. (This is beginning to change—NYU’s core curriculum is notably global in scope—but at a disappointingly slow pace. For instance, Columbia College still bases its core curriculum around Masterpieces of Western Literature and Philosophy and Contemporary Civilization in the West)

7.

So, while the students at our underserved school might not want or need to “analyze and take apart the Brontës and Louisa May Alcott”, the questions I ask, with a critical race theory-informed eye, are: Why

should they? Why

would they? Maybe they should instead be asked to analyze and take apart Olaudah Equiano, Phillis Wheatley, Solomon Northup, Frederick Douglass, Harriet Jacobs, Sojourner Truth, Harriet Wilson, W. E. B. Du Bois, Booker T. Washington, and Marcus Garvey—to name but a handful of possible writers that we could put on the syllabus. Such a study of what critical race theorists call “narrative analyses” (

Delgado and Stefancic 2017, Ch. 4

passim) would serve to awaken the moral and empathetic sensibilities and serve to, in the words of Mary Wollstonecraft, “…strengthen the body and form the heart. Or, in other words, to enable the individual to attain such habits of virtue as will render it independent”. For, as she continues, “…it is a farce to call any being virtuous whose virtues do not result from the exercise of its own reason”. From my personal experience, I will say that centering voices that are relevant to my students has been critical in maintaining their interest—and as contingent faculty, I am very conscious of the precariousness of my employment and the necessity of “keeping my customers happy” (as impossible as that might be in the age of COVID).

I am fully aware that my previous statements vis-à-vis CRT are controversial to some. Why throw out the entire historiography of a discipline for a new approach? What is the relevance of modern categories of race to, say, the Middle Ages? My point is that even such seemingly irrelevant-to-CRT subjects as medieval studies, like any professional study of the humanities, exist

only in the context of the academy. If we wish them to survive in this context, we must “get with the program”. Further, as I have argued previously, these approaches suggest fruitful new avenues of research (

Mondschein 2018). I know they have certainly given me new perspectives in my own writing on subjects as diverse and seemingly irrelevant to race as fencing books, medieval warfare, and the history of timekeeping.

The sentiments I have expressed in this essay are far from new, and in my opinion only describe a process that is well underway. My contribution to this discourse is that, given that the Crits seem to be well on their way to winning the argument in the liberal arts, the study of these subjects should not be limited. Rather, I demand the professional interpretation and teaching of the humanities by an empowered and economically secure faculty which is necessary for all students at all schools. The episteme must be spread as widely as possible. We cannot let the “woke” language and reasoning of social justice become the new Homer, a new shibboleth for a ruling class that remains unchanged. Not only does this do nothing to serve the greater good—it betrays the intent of CRT by placing what was supposed to be a tool of liberation in the hands of those who already have privilege. In other words, we cannot replace one class structure with another while doing nothing to reset the inequality that is at the root of injustice. The fundamental nature of the explainers—to justify a certain order of society—would then remain intact. Only by democratizing this knowledge can we effect a new order of the world. In other words, I am demanding a reinvigorated humanities professorate, and I hold that these subjects should be taught especially by people of color, LGBTQ individuals, and other historically excluded groups.

The question remains that, if the neoliberal university chooses to have no stake in this effort by defunding the liberal arts, who is to pay for all this education? Unless we are to rely on an army of adjuncts whom we pay poverty wages, such an effort will obviously require money. To ask historically disenfranchised groups to come into our classroom to teach this new canon and then to pay them less than a living wage is as unacceptable as continuing to teach a curriculum of dead white males. Achieving this may mean re-regulation in terms of accreditation and increased eligibility for grants and student loans, making such education, delivered by fairly compensated professionals, mandatory and broadly available. Perhaps it will require massive public investment in forms such as scholarship funds, direct aid to colleges, and student loan forgiveness. It will no doubt need to be litigated at some point. The critiques from the right suggest themselves—but consider, for a moment, that this public investment is already happening: The school headed by our professor-firing, Brontë-hating college president is run by white administrators who are paid ample salaries from federal money (in the form of student loans and Pell grants) given to Black and brown students. Because of the pandemic, increased public investment in the higher education sector is already necessary to prevent collapse and college bankruptcies. I ask only that this initiative be expanded to reinvest in the liberal arts, and that the liberal arts be considered as the spearhead in the fight for equality. From the perspective of CRT, to do otherwise is to turn a blind eye to white supremacy, and therefore to be complicit in it.