Abstract

Sonic rhetorics has become a major area of study in the field of rhetoric, as well as composition and literature. Many of the underlying theories of sonic rhetorics are based on post-Heideggerian philosophy, new materialism, and/or posthumanism, among others. What is perhaps similar across these theories of sonic rhetoric is their “turn” from language and the human in general. This short essay explores sonic rhetorics by examining three temporal dimensions found in language. Specifically, the essay focuses on the more obvious sonic dimensions of time in prosody, and then at deeper levels temporal dimensions in a couple of brief but revealing examples from ancient languages (classical Greek, and Biblical Hebrew). Further, this essay suggests some ways in which time is related to ethics in practice and action. For example, just as time is involved in the continuous creation of our increasingly vast, expanding, infinite but bounded universe, Levinas might say that time is necessary to create the ethical space, or perhaps “hypostasis,” one needs for the possibility to encounter “l’autre”—the Other. Beyond prosody, propriety, even kairos, are hidden temporal dimensions of language that may render sonic rhetorics forms of ethical practice.

1. Introduction: A Background of Sound

Sonic rhetorics is undergoing an increasingly loud and noticeable boom. A growing number of scholars in cognate rhetorical fields have turned their auditory attention to sound as meaningful if not fundamental in both teaching and researching rhetoric, writing, literature, and philosophy, e.g., (Ahern 2018; Detweiler 2019; Gunn et al. 2013; Hawk 2018a; Measel 2020; LaBelle 2018; Novak and Sakakeeny 2015; Osborn 2016; Overall 2017; Patterson 2020; Rickert 2005, 2013; Rickert and Salvo 2006; Stedman 2012; Sterne 2012; Stone 2015). Generally, sonic rhetorics concerns itself with the multiple dimensions of rhetoric as sound. Sonic rhetorics, like “rhetorics” generally, can include literary as well as nonliterary texts, events, objects, natural/ecological sounds, etc., either in combination with visual or virtual stimuli or in isolation, as aural-born phenomena and/or as acoustic elements in soundscapes or larger entangled environments (Patterson 2020; Rice 2012, 2020).

The study of sound in rhetoric as sense (or nonsense)—the possible “meaning” of sound in language—can be said to have begun with (Plato 1961a, 1961c) but also may be found in more pre-Socratic lyrical poetry (Walker 2000), and perhaps even earlier in pre-Homo sapient pre-history (Rickert 2016). Sound was the hallmark of sophistic rhetoric that Plato fought against, in which style is a form of knowledge (Enos 1993; Kerferd 1981); in late Ciceronian theory of oratorical rhythm as an aural, temporal intuition of “truth” (Cicero 1939, 1942; Leff 1989; Mendelson 1998; Katz 1996); Medieval and Renaissance debates about Attic vs. Baroque prose styles and methods of figuration and scansion (Croll 1989; Ong 1958; Ramus 1983); research into the sophistication and intricacies of prosodic and musical notation of the song-poems of the Troubadours (Whigham 1979); and the 18th century Elocutionary Movement with its renewed emphasis on human (and nonhuman) sound, delivery, and gesture/motion (Sheridan 1968; Austin 1966; cf. Bulwer 1974; Darwin 2009; Hawhee 2016). And this is just the briefest history of the musical properties of language in the field of rhetoric!

Although the study of sound in modern rhetoric and composition can be said to have begun with the images and metaphors of writing as “felt sense,” “dissonance,” and “musical organization” (Perl 1980; Odell 1993, p. 232; Elbow 2006), respectively, the birth of late 20th- and early 21st-century approaches to sonic rhetorics has been attributed to Katz’s (1996) book, Epistemic Music of Rhetoric (Gries 2019; Hawk 2018a). However, the contemporary study and teaching of sonic rhetorics goes far beyond old-fashioned approaches, such as Katz’s, that analyze literary (and nonliterary) language and style as music, and affective and/or cognitive responses to sound sound (cf. Ceraso 2018; Measel 2020). These new approaches include post-Heideggerian and/or phenomenological studies of sound and/or posthumanistic tracings and analyses of technological production and disseminations of sound (e.g., Rickert 2013; Rickert and Salvo 2006; Hawk 2018a, 2018b).

Given the diversity of this “subdiscipline,” it is only to be expected that different conceptions, definitions, and even terms of sonic rhetorics (“the music of rhetoric,” “sonic rhetorics,” “aural-born rhetorics”) have emerged. Some of the subsequent treatments of rhetorics variously called (or not called) sonic rhetorics are predicated on senses connected to the human body, and some apparently on senses disconnected from the human body—refocused on or furbished by “natural” sounds (Ahern 2018) or technological sounds (Rickert 2013) or aesthetic sound (Osborn 2016). Some sonic rhetorics consider magical, spiritual psychic, or psychagogic exploration (De Romilly 2013; Rice 2020; Stephens and Katz 2019). Some (pre)sonic philosophies and rhetorics zero in on and wrestle with the movement of the body, including natural bodily “functions” and their symbolization (Burke 2007; Hawhee 2009; Katz 2015b; Rueckert 2007), as well as the sensuousness movement of the symbolic form of language in consciousness (Cassirer 1955; Katz 1996); physical motion and dance (Hawhee 2013); theatre sound (Kaye and Lebrecht 2015; Patterson 2020); and the rhetoric of every kind of music, including jazz and hip-hop (Clark 2015; Carson 2017).

What is perhaps similar across many of these theories of sonic rhetorics is their turn away from language (the non-linguistic turn), and the human in general (the non-human turn). This is not surprising either, given the scientific, philosophical, and cultural contexts of new materialism and posthumanism (e.g., Barad 2007; Barrett and Boyle 2016; Bryant et al. 2011; Harman 2018; Hawk 2018a; Holmes 2013; Ahern 2018; Ceraso 2018; Detweiler 2019; Overall 2017; Pilsch 2017; Stone 2015). I will not critique or criticize any of these theories and studies. Rather, I applaud their diversity and encourage their development in (re)focusing the field of rhetoric on “the natural world”—on the nonhuman as well as aesthetic (sonic), on objects and animals and events in worsening physical climates and the social environs of the Anthropocene (Comstock and Hock 2016; Morton 2009, 2012, 2013; Propen 2018; Zylinska 2014). I will only point out in passing a few caveats and concerns1. What I want to do in this little essay is propose that there still may be some hidden sonic dimensions of sound “left behind” in language, and that they have some attendant ethical components and implications that might be important to consider in sonic rhetorics. This ‘linguistic (re)turn’ necessitates revisiting language via rhetorical and stylistic analysis, as well as some etymological work based on classical Greek and esoteric hermeneutics based on Biblical Hebrew, and therefore are epistemologically registered and referenced in the terms of the limitations of the human senses, mind, science, and technologies—the vagaries of human response and the uncertainties of all human knowledge and experience. This short essay quickly explores three dimensions of language underrepresented in sonic rhetorics: (1) Prosody; (2) Etymology; (3) Orthography.

Because a foundational “key” to sound (and ethics) is time, I will advance some notions of time not usually talked about, and then (1) touch on some more obvious sonic elements of time in prosody or poetics; (2) quickly dip into the history of a single passage and word of classical Greek and its temporal translations, and finally (3) point to a hermeneutic approach to the letters of the alefbet themselves as well as a meaningful temporal dimension of grammar in Biblical Hebrew. My choice of passages, languages, and methodologies is not systematic in the ordinary sense; rather, it is driven in part by the efficacy of examples, by my own hermeneutic access (and limitations) to different languages, and some hidden but highly revealing and significant sonic dimensions of time in those languages as ethical actions in “literary (and nonliterary) practice.

Before proceeding with these three analyses, we must quickly (re)examine our notions of time.

2. (Re)Introduction to Time in Rhetoric/Rhetoric as Time

The concept of time or timing in rhetoric is an ancient one. We have already, albeit quickly, reviewed the attention to the study of time in the history of rhetoric in the study of oratory, elocution, prose style, and song. A concern for propriety in eloquence, the perfect unity of form and content at every moment of persuasion (Cicero 1939, 1942), and kairos, the relationship between rhetoric and ever-changing historical context and thus discourse as a time-event rather than a static object (Miller 1991), are important considerations of time in rhetoric. Of course, one of the “keys” to the study of sound (in language or music, in linguistic or nonlinguistic objects and events) is time. Just as time in astrophysics seems to be involved in the continuous creation of the increasingly vast, infinite, and unknowable physical space, so too with phenomenological-ethical time-space. For example, for Heidegger time allows the possibility to one’s death as the “Event Horizon” and source of Dasein, of true Being-in-the-World (Heidegger 2010a). For Levinas, another ethical possibility of the time-space relation/expansion is to encounter, through increasing Alterity, or “hypostasis,” l’autre—“the other” (or “Other,” perhaps G/d),” which for Levinas may be the ultimate ground and goal of ethics (e.g., Levinas 1981, 1987, 2000).

But the issue of time in rhetoric (beyond historical chronology or audience measurement, beyond propriety, beyond kairos, even beyond prosody in prose), is immediately engaged anew in other possibilities of hidden sonic dimensions of language and literary practice and its relation to ethics. In the time-space constraints of this essay, I will investigate at least three dimensions of rhetorical–linguistic time that are perhaps concealed in the languages in which we live. Somewhat like Heidegger, but with so much less knowledge and moving in the opposite direction—into language rather than through and away from it in the ultimate search for Alethia (truth) through Dasein (Heidegger 2010a; cf. Heidegger 1971a, 1971b, 1977, 2010b, 2014)—I will attempt to “unconceal” three aural–temporal dimensions of language that might underlie studies of sonic rhetorics as ethical action in literary practice. These three dimensions are: (1) prosody; (2) etymology; and (3) orthography. We will see that time and ethics are involved in each one of these dimensions.

How should we think about time? The following are some assumptions and assertions.

- (1)

- As Einstein postulated, time is a fourth dimension of space; but as String Theory and Quantum Entanglement (Greene 1986; Barad 2007) predict, there may be multiple, perhaps countless dimensions of space, and thus multiple dimensions of time—or no discernible difference between time and space at all. Size-wise, these extra dimensions of space could be the tiniest of pockets, to entire alternate universes, to all universes—a theory the late (Hawking 1988) also entertained.

- (2)

- In his undefended but not published doctoral dissertation, the poet and philosopher T.S. Eliot (1989) argued that there are a least two dimensions of time: physical time, and temporal consciousness—time as we experience it. However, if these two dimensions are not in sync (and how can we know whether they are or not), the results are temporal crises in the history of empiricism and “objectivity” that parallel and rival the epistemological problems of language/thought and spatial referents which have haunted Western philosophy and science from Heraclitus to Quantum Entanglement (see Kerferd 1981; Barad 2007).

- (3)

- We do not really know what time is. Unlike space, time is invisible. Like causality (Hume 1999), we only assume its potential, see its (chronological) effects. We do not see the law of causality and have no other experience of it. So too with time: we can’t see how it operates/acts. And unlike space, in which we move in three dimensions, it seems we can only move forward in time. In addition to its physical invisibility, time as a process of expansion toward death has been given a role in 20th century philosophy of ethics, where it becomes the “Event Horizon” for Dasein and a possible realization of fuller (human) being (Heidegger 2010a), or an eternal moral space for the discovery of Alterity—where meeting the Other becomes possible, and thus a primary grounds of a new ethics of relationships (Levinas 1969, 1987, 2000).

- (4)

- We cannot stand still in time as we can do in space, even if we stand absolutely still in space (even in death we continue to decay, for most organic and inorganic entities until there is nothing left). We move in and through time, and time moves in and through us.

- (5)

- Time may not only be a dimension; it also appears to be a force, a force that moves, a force that moves everything with it—a tremendously destructive force that slowly ravages everything, both animate and inanimate objects alike. (Hence the urgency we find in Being and Time for the fully cognizant human to recognize his/her own death, embrace it, and to give it and life full meaning.)

- (6)

- But time also would seem to be a force that opens with space, not only for the otherwise anonymous self to move into aware subjectivity (Levinas 2001), or to move in space to a temporal position that makes possible an encounter with (an)Other (Levinas 1987) and perhaps ultimately—but never—G/d (Levinas 1969, 2000); but also in the physical expansion of the universe a million miles per second in every direction. The action of time as a force, then, is an expression in language (Steiner 2013; cf. Levinas 1981) of metaphysics as well as science—which makes and takes physical as well as ethical movement and consciousness outward and into the future even possible.

- (7)

- Diane Davis (2010) argues that for Levinas ethical obligation is “preoriginary,” which “temporally” probably would place it before the big bang and before the creation of time and space, making language ‘sacred’ and rhetoric “first philosophy.” For Levinas (1981), this prelinguistic reality, a phenomenological “realm” of being that exists outside time and space “beyond essence” (Levinas 1981), is the ground of Alterity, the first possible “encounter” with (an)Other, and “inessential solidarity” (Davis 2010). A reading of Levinas’ earlier work (e.g., Levinas 1987, 2000, 2001) might imply that subsequently, without time (and space), whatever time is, we might not be able to move, morally or physically at all: we would be frozen in whatever space is, without motion—and if sentient, painfully naked consciousness shivering in a void. (But cf. Levinas 1981.)

- (8)

- It is in the property of time as a physical force, as a movement ripping open space, opening the universe before us (or as local motions also at-a-distance–“Quantum Entanglement”) where we begin to hear tone, time, sound which (perhaps like ethics for Levinas), seems to arrive out of a primal ‘nothingness’ (Levinas 1981; Zuckerkandl 1956). But if we are looking to material time for a physical counterpart to the nonspatial, atemporal “preoriginary” basis for “inessential solidarity” as the potential ground of ethical relations (Davis 2010), time as a moralizing physical force may serve that role in Heidegger’s concept of Being, but it may not do so for Levinas. “The title and the content of Otherwise than Being or Beyond essence alert us to the priority Levinas gives to his ongoing contestation of Heideggerian thinking. Otherwise then Heideggerian being; beyond Heideggerian essence” (Cohen 1998, p. xiii; cf. Katz and Rhodes 2010). We will return to these issues at the end of the essay.) Regardless, it seems evident that nonlinguistic sonic experiences, from cosmic radiation from the Big Bang to music, whether ethical or not, reaches and affects us through language and the world, which acoustically command and ethically demand that we hear, listen, respond, and attend to sound, if not also to our ethical responsibility to (the) face (of) the Other (cf. Davis 2010). Time as a physical force opens up language and the world through science and poetry (see Heidegger 1971a, 1971b, 2010b, 2014).

It is here that we will turn to our first example of the hidden temporal dimensions of sonic rhetorics in language, in this case in prosody, poetics—and its moral positionings and literary practices as sound.

3. The Prosody of Time and Ethics

Certainly, we hear and feel not only the force of time in the rhythm of a poem that is musical and performed, but we also understand how poetry uses time, as music does, to create and toy with affective and cognitive expectation of emotionally meaningful sound (see Meyer 1956; Zuckerkandl 1956; Huron 2008). But if we are especially attentive readers (or talented writers), we also can create and/or hear ‘linguistic pockets of time’ in the sounds of poems as human-made sonic objects. In the rhetoric of poems as human sonic objects, these linguistic pockets of time can be predicated and predicted on traditional prosodic elements of poetry, poetics (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Pockets of linguistic time in prosody.

Poetry, especially formal poetry, uses forms and styles to explore time by routing ideas and sounds around the nooks of line breaks, the crooks of rhyme, the running repetition of expected and heard beats (meter and rhythm), the crannies of specific forms that expand and contract and reflect the back/wash of recurring refrains and rhymes, or flow steadily on. These linguistic pockets of time, these prosodic elements we create and hear in poems, become the sonic rhetorics of poems as sound. Poems as sonic objects also create aural and temporal arguments that are ethical (see Katz 2017; Stephens and Katz 2019). However, with these traditional prosodic elements we have direct but not unproblematic access to the temporal dimensions of poems as sonic objects, and their ethical arguments (see Katz 1996; Whigham 1979; Croll 1989; Measel 2020) via revealing albeit still limited analysis.2 These linguistic pockets of time created in the rhetorical bodies of poems as sound do not always point outward and are not directly connected to external referents (Heidegger 1971a, 2010b). Yet rhetorically, time, invisible except to the ear, can ethically critique the referential meaning/spatial content of poem and culture. But it is almost always the case that spatial, referential meaning will ‘visually overrun’ the temporal dimensions of poems, which then become objects of interpretation rather than performance (Katz 1996; cf. Katz 2017; Stephens and Katz 2019). Thus, contextual content and culture is often useful or necessary to make relatively specific sense of the “meaning of music” (Meyer 1956). Thus, the temporal dimensions of poems as sonic objects are easy to rhetorically miss, especially when the content itself is highly ethically charged. The following volatile villanelle composed by the author from phrases spoken or tweeted is a “perfect” example of how the rhetoric of a poem as sonic object itself may constitute and act/enact temporally ethical arguments. Because I am going to ask you to ignore context and foreground the prosodic dimensions of time, I am going to blind the poem as much as possible. We do not have to and will not discuss the content of the poem per se. Please listen, and we will “see” you on the other side.

Untitled

“What the hell’s happening out there in space?Believe me, there’s no man-made climate change!My people tell me it’s a big disgrace!”

“Mar’s next—best people—I don’t care race.A Space Force will also be tremendous.So what the hell is happening in space?”

“They’re bringing drugs, they’re bringing crime—that face!We have no borders; they’re laughing at us!Many say it’s a terrible disgrace.”

“The Putin witch hunt is a huge mistake.If you’re listening, let’s be friends, Russia.(But what the hell is going on in space?)”

“The news is all made up, totally fake!There’s no obstruction, no collusion, no quid pro quo.It’s a hoax, witch hunt, disaster, disgrace!”

“No puppet, no puppet: I will invade,any sh’ holes with oil if they don’t have white folks.Just look what’s happening in outer space.”

“I’m like a genius—a very high IQ—smarter than, than my generals!Who knew it would be so complex?Fine people on both sides: it’s a disgrace.”

“I’m shutting down the government, closing the border, will separatefamilies to prevent more American carnage.And also what happens in outer space.”

“We need to build that wall; but who will pay?Mexico!! Our nation’s being overrun by savages!It’s a sin, what’s happening, a disgrace.”

“I read somewhere, and I’ll say it again:Wouldn’t it be great if Putin were our friend?Then what the hell is happening in space?Whatever. It’s a total disgrace.”

It is very difficult to get beyond the speaker and the referential–ethical meaning expressed here (they are right in your face—and not in a Levinasian way (Davis 2010), but rather the opposite). But can you hear time through the screed? Much of the poem is obviously referential, a dialogic interaction between the personal/cultural sphere of affect/art and the public/political sphere of discourse that does the rhetorical work of criticism and raises ethical questions all on its own. But if we stop there, prosody will teach us nothing about time and ethics in the language of the poem as a sonic object. The literary form of the villanelle in all its temporal dimensions, holds and remolds, squeezes, cajoles, and critiques the referential and contextual content of the poem. The villanelle qua rhetorical–ethical action temporally manipulates and comments through overall form (musical organization), line length and breaks (duration), rhythm and meter (time in rhetoric), and the sonic repetition of refrain and rhyme pattern (rhetoric in time). These temporal dimensions (as prosodic pockets) of poems—sonic objects made out of language—critique content and each other in real time.

- −

- The villanelle reveals things that would not be revealed in prose or any other poetic form.

- −

- The villanelle’s overall form, the repetition of refrains and lines, the restricted rhyme scheme, and the usually tight syllabic line lengths (10 syllables) or meter (iambic pentameter) are all temporal elements that do sonic and rhetorical work.

- −

- Because of the constantly recurring lines (the first line of the first tercet reappears as the end line of stanzas 1, 3, and 5, and the penultimate line of the quatrain; the last line of the first tercet reappears as the end line of stanzas 2 and 4, and the last line of the quatrain), and to some degree a lack of variation, the villanelle is the perfect form to capture and reproduce a speaker’s own penchant for repeating whole phrases, as well as using circular logic.

- −

- This villanelle is longer than the traditional villanelle of five tercets and a quatrain. Instead of six stanzas, it has ten. This poem physically recreates a speaker who “runs over time,” goes off-script, adlibs, all the while circling around and repeating himself, almost verbatim. We see this in the line length too, in places where, in conjunction with content, the lines deliberately “run over” the meter.

- −

- If line length as duration constitutes temporal ethical criticism, Lines 1–13 are in perfect syllabic meter for the villanelle: ten syllables each, establishing the standard. However, the syllabic meter of the villanelle form allows lines to run over and amok (especially noticeable when the line runs way over), exposing the ramble, ruckus, and rot (see L14, where line length calls attention to the fabrication, and L19, where line length calls attention to itself as an empty, stupid boast. L22 and L26 create similar sonic/temporal effects).

- −

- L4 and L7, in maintaining the 10-syllable count, force some other figures of omission (Quinn 1995), in this case ellipses, to linguistically and temporally unconceal prejudice, as well as broken grammar and non-sequiturs.

- −

- There also are lines where the form of the speaker (temporally if not physically, as it were) come up “short” (nine or less syllables), as in L20 and L31, thus critiquing the statement that time ethically undermines.

- −

- A high level of generality and limited diction of the poem is highlighted by the traditional villanelle’s syllabic metrical count and recurring refrains and lines.

- −

- Rhyme (sound in time), along with rhythm and meter (time in sound) are temporal dimensions par excellence. In this villanelle, the rhyme of the two refrain lines are fairly consistent: “space,” and “disgrace,” two words that are constantly repeated, creating something like obsession. But all “b” rhymes throughout the poem, although clever, introduce sour rhyme into the temporal scheme: “change,” “tremendous,” “us,” “Russia,” “folks” “complex,” “carnage,” “savages…” The off-end rhyme, sometimes rather distant, jangles across the time-space of these lines, as well as within and across lines [internal rhyme].

The villanelle as a sonic object in language—including and particularly its overall form and style, its refrains, its rhyme scheme, and its line lengths and breaks—is a direct temporal form of ethical criticism, which Cicero knew was a “natural intuition possessed by everyone” (1942) and the final arbiter of truth (1939). And it is a good thing that it is natural, for who reads at this level but literary and rhetorical scholars? While many of the sound effects are obvious to us, and have some kind of affective effect on listeners or readers, the temporal “value” of poetry as sonic objects are rhetorically more esoteric and obscure than ordinary language use, where the sound is still heard but the ethical role of time is often hidden and goes undetected.

4. Deep Sound, Time, and Ethics

While not as theorized as prosody which becomes a basis for understanding the sonic rhetorics of poetic objects, or as historically tectonic as the significant variations and Weltanschauungen of different languages, there are also multidimensional pockets of linguistic time created by and contained in the etymology of words—what we might refer to as ‘deep sound’. These pockets of time are not merely the result of the chronological development of the denotations and connotations of words spoken and written in any language, but also are temporal distortions of diction that result with the always “inaccurate” and already metaphorical usage of each word and its vicinity, at each layer of linguistic history. Because of the passage and upheavals of history, local time distortions of meaning, with ethical implications, also can be seen in attempts at translation, which are usually problematic but also revelatory.

For an apt example of a discussion about music and language in classical Greek, let us turn to W. D. Woodhouse’s translation of the Plato’s Gorgias (Plato 1961b). There (502c-d) Plato has Socrates ask:

“φέρε δή, εἴ τις περιέλοι τῆς ποιήσεως πάσης τό τε μέλος καὶ τὸν ῥυθμὸν καὶ τὸ μέτρον, ἄλλο τι ἢ λόγοι γίγνονται τὸ λειπόμενον”

(phere dē, ei tis perieloi tēs poiēseōs pasēs to te melos kai ton rhythmon kai to metron, allo ti ē logoi gignontai to leipomenon)

“[I]f you strip [περιέλοι” (perriéloi); inf. Περιαιρέω] poetry of its music and rhythm and meter, wouldn’t what remains be nothing but speech?”

If we “take a moment” to focus on the Greek word Plato uses for “strip” here, “περιέλοι,” we might strain to hear other dimensions of time—not only just below the surface, in the chronological, etymological history and/or the surrounding grammar of each word, but in translations as well. (Indeed, coded deeply beneath any text is the creation of “other texts” based on the long history of each word and their differential relations, but now newly assembled, although their organization is far less coherent or intelligible. This temporal ‘subtext’ is further concealed by translation, as well as contemporary usage—but is always and necessarily present nevertheless—a hermeneutic dimension of texts that Heidegger was acutely aware and made central to his philosophy.)

These hidden dimensions of linguistic time, located around, under, and through each word and its grammatical usage, can be understood as pockets of sonic rhetorics. The sonic rhetorics created by etymologies (in translation or not) are based not only on horizontal duration, as is the case in poetry (e.g., the line), but also on vertical duration and extension, which is also the way metaphor works (Boyd 1993; see Appendix A). In this case, the act of stripping is vertically ordered in Table 2 by my admittedly subjective judgment concerning the increasing velocity of the denotation and connotations of the translation of “strip.” Here, the relative and ‘ethical soundings’ of the language becomes equated with the speed and thus violence of the rhetorical act. (The detail in Table 2 was gleaned and quoted from the Tufts University’s Perseus Project/Greek Word Study Tool [2019]).

Table 2.

Etymological pockets of time in translations of the Greek word περιέλοι, “strip”.

My point if not my argument here is that the length of time it takes to say a word, or to say it in translation, bears some relation to and in effect temporally recreates/represents for listener or reader the experience as a sensuous movement of sound as intellectual content in consciousness (Cassirer 1955), or as a “symbolic act” (Burke 1966), and so has at least some validity, since the act is taking place through the sonic rhetorics of language—the sound of the words. The same sonic reality occurs when you look up other possible Greek verbs for “strip.” The alternate words/translations not only point to different grammatical relations, spatial referents, and sometimes wildly different meanings, but also contain in themselves actions of varying durations as part of their definitions, highlighting not only the difficulty of translation but also the varying temporal dimensions of meaning, and their ethical import in a text. (I deliberately discuss the sonic rhetorics created by etymological time and velocity of words rather than the grammar of verb tenses in classical Greek. The next section looks at Hebrew grammar.)

5. Ethical Letters and the Sonic Creation of Time

There seems to be another rhetorical tradition, rooted in another classical language, in which time as well as space are believed to be created in language itself, by and through the letters of the alphabet—a sonic rhetorics in which the world is text, reality (already) written. I am not talking about postmodernism, with its focus on signification without final signifieds, although they are closely related through scholars like Derrida (1976), Handelman (1983), and Bloom (1975) and in part are derived from this ancient language and tradition begun over 5781 years ago and still used in sects of different religions, although relatively unknown outside the Jewish religion. This sonic rhetorical dimension of language and grammar, and the alphabet itself, though often heard, is relatively unknown or not understood, even by the Jewish people, many of whom nevertheless participate in it in services and rituals, or hear it in sermons without realizing its rhetorical significance (Katz 1995a, 1995b, 2003, 2004). (This was partly deliberate, as the ancient rabbis, sages, and mystics treated this knowledge as sacred, dangerous, forbidden knowledge). As Joseph Dan (1998) comments, it is very difficult to flip the relation of language and reality, and to think that texts spoken and written are reality—sonic reality I would add—and that the physical objects in the world are the signifiers. This Jewish tradition is not only ancient, but also deep and rich, and I will only have time to barely scratch the surface of one letter, and point to some other work I have done for those interested. I have dubbed this tradition “the rhetoric of the Hebrew alefbet,” a Jewish mainstream theory and practice perhaps somewhat different in its persistence if not wholly unique from the Greek and Roman hegemonic one we have inherited, and a theory and practice still adhered to in different ways in different branches of Judaism today.

In past work, I have argued that the rhetoric of the Hebrew alefbet might constitute an ontological, or perhaps more precisely, an orthographic basis for what I have called a “Jewish sophistic” (Katz 2009). In “The Epistemology of the Kabbalah: Toward a Jewish Philosophy of Rhetoric” (Katz 1995a), I argued that based on the alefbet, this Jewish sophistic, not chronologically but philosophically, generally speaking would fall somewhere between Platonic and sophistic epistemological positions. Further, I have examined how the Hebrew Bible (the Tanakh) itself might constitute or at least represent a rhetorical “theory” quite different from most Greek and Roman concepts of persuasion (Katz 1995b, 2003, 2015a). And like Harold Bloom’s reading of the Kabbalah in Kabbalah and Criticism (1990), we might read this tradition—begun in the opening words of the Tanakh—with a set of hermeneutical principles known as the Baraita of the 32 Rules (see Strack and Stemberger 1996; Katz 2015a). Without getting into detail or going into depth, these principles were developed through the Rabbinic period (200 BCE–400 CE) while under Roman occupation, along with more fanciful Midrash (and to a lesser extent in the more legalistic and logical Talmud), and perhaps reached their fullest fruition in the various Kabbalistic texts that arose from the 1st through the 16th centuries. Alive and still learned, practiced and actively used today in sermons of all denominations, the latter five of these hermeneutic principles in particular might seem for us to be part of a different “sophistic” rhetorical tradition. For believers, these hermeneutic principles are not merely concerned with invention and persuasion, but also and ultimately with creation. And not merely the creation of ‘social-epistemic’ reality, but of physical reality—the entire material universe, space and time included.

In three major religions that draw on the Tanakh, G/d, creates the world/universe in the first line of Genesis (read right to left): בְּרֵאשִׁ֖ית בָּרָ֣א אֱלֹהִ֑ים אֵ֥ת הַשָּׁמַ֖יִם וְאֵ֥ת הָאָֽרֶץ ← (Bereshith bara Elohim eth hashshamayim v’eth ha’arets). “In the beginning G/d created the heaven and the earth.” And how does G/d do this? Simply by speaking: וַיֹּ֥אמֶר אֱלֹהִ֖ים יְהִי־א֑וֹר וַֽיְהִי־אֽוֹר ← (Vayyomer Elohim yehi-or vayehi-or) “And G/d said ‘Let there be light and there was light’.” G/d speaks creation into being. (Some mystics believe that G/d merely opened his/her mouth, and out of this divine silent sonic act the universe was born.) In this rendition of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, G/d is the master rhetorician. This is the ultimate power of rhetoric for which rhetoricians long—to create not just symbolic action, consubstantiality, a social construction of reality, but “physical reality” itself see (Burke 1952, 1966; Handelman 1983). Further, in the Jewish tradition, especially the esoteric (and guarded) mystical one of Kabbalah, God does not just speak creation; G/d writes it down beforehand, using the Hebrew alefbet. In Judaism, as in postmodernism, (e.g., Derrida 1976), the world is already written! And it is “settled” convention that writing literally comes first: Moses was given not only the Ten Commandments, but also the written Torah on Mt. Sinai; or Moses wrote it down; or… (see Handelman 1983; Katz 2003). The Oral Torah was compiled much later, during the Rabbinic period, finally giving us the Talmud.

As I have also suggested, the Jewish G/d is thus ‘the ultimate sophist’ (Katz 2009). En arkhêi ên ho Logos—“In the beginning was the Word” John (1:1) declares. But in Judaism, the Word is not made flesh for sacrifice and redemption, as it is in Christianity; the Word remains language, the world a sonic rhetorics—the coughing, smoldering, broken, cryptic, musical remnants of spoken and written letters left over from the first act of linguistic creation: the language of the universe. G/d grows more and more distant and eventually disappears in the original Hebrew Bible when compared to Christian versions of “The Old Testament” (Miles 1995); only the alefbet remains. In Judaism, G/d is ultimately unknowable, as well as quite changeable (Miles 1995). And in Hebrew, G/d’s holiest ‘incarnation’ is a Name, the Tetragrammaton yud, hey, vov, hey (Figure 1):

Figure 1.

The Tetragrammaton (read right to left).

This Name, usually transliterated as Jehovah or Yahweh, is literally unsayable—physically as well as by taboo and tradition. This too is “sonic.” But what does it have to do with time and ethics? In Kabbalah and the mystical tradition generally within Judaism (as well as in astrophysics [Hawking 1988]), creation starts with the smallest point possible, in the Eyn-Sof—the inconceivable “nothingness,” which is also G/d). This is a sonic rhetorics of hidden temporalities “in ethical action”—the sound of language/reality itself as spoken by G/d, and reembodied in the Torah and Talmud, and in every letter of the alefbet. To conclude our discussion, then, let us focus on just one letter—the third of the four letters of the Tetragrammaton, vov—in itself, and in relation to the other three letters of the Tetragrammaton, and the sixth letter of the Hebrew alphabet with which by some accounts G/d created the universe. In Kabbalah, and the mystical tradition generally within Judaism, creation starts with a point, the smallest of the Hebrew letters, the Hebrew letter, yud—  —and extends and expands outward, and then down through the vov:

—and extends and expands outward, and then down through the vov:  . As Harralick writes,

. As Harralick writes,

—and extends and expands outward, and then down through the vov:

—and extends and expands outward, and then down through the vov:  . As Harralick writes,

. As Harralick writes, [T]he [yud is in a] state of concealment and obscurity, before it develops into a state of expansion and revelation in comprehension and understanding. When the “point” evolves into a state of expansion and revelation […] it is then contained and represented in the letter ה [hey]. The shape of the letter ה [hey] has dimension, expansion, breadth […] to indicate extension and flow downward to the concealed worlds. In the next stage this extension and flow are drawn still lower into the revealed worlds […]. This stage of extension is contained and represented in the final letters[vov] and ה [hey …].

[vov], in shape a vertical line, indicates downward extension.

(Zalman, qtd. In Haralick 1995, p. 156)

One result of this interpretation or “drash” on the letter vov/the Tetragrammaton, is that in it we hear that G/d creates the entire universe and everything in it, including all time and space through the speaking and/or insertion of the letter of the Name into nothingness, into the void (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The Vov and Moral Space-Time.

I have dubbed the massive explosion of letters as objects and events that followed this sonic rhetorical act the ‘Jewish big-bang theory’ (Katz 2003). This hidden linguistic act sonically creates a rhetorical and physical reality, a spatial–temporal and still expanding realm as an orthographic, moral universe where the Hebrew letters themselves are presumed to be ethical, sacred, holy, and are treated as such by the observant (see Katz 1995a, 2003, 2004). In another Kabbalistic tradition, that of Rabbi Isaac Luria, the omnipresent G/d must withdraw from a tiny space in order to allow room for the creation of the universe (Vital 1999; cf. Burke 1966 on Spinoza). In sonic production terms, this rhetorical physical act might be akin to creating, in the nothingness of a digital file, the necessary “acoustic room” into which sound or writing can then be recorded. One might relate this to Levinas’ philosophy of ethics (passim) as well, where time (and space) are necessary for the possibility of Alterity, which might lead to the face of the Other(s), and ultimately G/d… but probably not all of G/d, for Levinas’ philosophy can be understood at least in part to derive in complex ways from Jewish tradition as well (e.g., Levinas 1981, 1990a, 1990b, 1998).

But there is another sonic feature of the Hebrew letter vov that involves issues of grammar and interpretation. The vov is almost always translated as the conjunction “and,” and can be attached to almost any word. Grammatically, “AND” is a coordinate conjunction; it makes things equal. “And” is also a time referent, a temporal marker (a sentence that begins with “And” explicitly implies that something came before: “And G/d said…”). And “and” can rhetorically create the illusion of simultaneity in language, a medium that unfolds lineally. And think about the figure of speech, polysyndeton, and the deliberate repetition of coordinate conjunctions (Quinn 1995): “and” rhetorically creates a sense of multiplicity, of prolixity, of procreation, if for no other reason than because there are literally more words! In the King James version of the Bible, the vov is translated as “and,” giving us all of these conjunctions:

And God said: “Let there be light.” And there was light. And God saw the light, that it was good; and God divided the light from the darkness. And God called the light Day, and the darkness he called Night. And there was evening and there was morning, one day. And God said: “Let there be a firmament in the midst of the waters, and let it divide the waters from the waters.” And God made the firmament from the waters which were above the firmament; and it was so. And God called the firmament heaven. And there was evening and there was morning, a second day.Bereshith (Genesis) 1:1–1:8

But in Biblical Hebrew, vov has several additional grammatical functions that relate to sonic rhetorics in fundamental ways. In one of these functions, vov ההפיך— Hahipuch (the “vov of reversal,” also called the “vov conversive,” or the “vov consecutive”) not only gives us all those conjunctions “and,” but also when attached to a verb can shift its tense (a temporal dimension of Hebrew totally lost in translation). When the vov of reversal is attached to a past tense verb (the perfect tense because the action is completed), the vov often changes the past tense in Biblical Hebrew into the future tense (the imperfect tense), and vice versa. We have already seen this: יְהִי־א֑וֹר וַֽיְהִי־אֽוֹר ← (yehi-or vayehi-or) “Let there be light and there was light.” Note that in Hebrew the form of the verb (highlighted in green) is the same in both cases: the first, future/imperfect tense (used as an imperative), preceded by the vov of reversal, is repeated in the same form, even though it is translated in and out of Hebrew as if it were past/perfect tense (which would be היות–haya—“there was”). Without the grammatical vov of reversal, or its sonic rhetorical effect, the translation would read, and we would hear: Let there be light and there will be light. (Heresy!)

This kind of detail regarding the grammatical and rhetorical functions of letters and parts of letters is very typical of the rabbis of Talmud and Midrash (see Handelman 1983; Katz 2015a). But why and how is this significant for us? Because this “theory” sonic rhetorics and time is built right into the grammar and alphabet of Biblical Hebrew, into the letter vov. The effect of this rhetoric of the alphabet, in this instance alone, is to create not only an alternate rhetorical theory and tradition, but timelessness, eternity in the text. And with Levinas, an originary letter to which to respond (cf. Davis 2010). Because of vov of reversal, in Biblical Hebrew, the first act of creation in the Five Books of Moses, through the Prophets, to the last pages of the Writings, has happened, is happening, will always happen! (We see this in the Passover seder, for instance, where G/d annually frees the contemporary reader/celebrant from bondage in Egypt.)

This essay is not a Luddite, or perhaps more accurately, Antediluvian tract on sonic rhetorics. I have written before on the possible relations of the rhetoric and/or hermeneutics of the Hebrew alphabet, Object-Oriented Philosophy, and the Anthropocene (Katz 2015a, 2015b). The grammar of the Hebrew alefbet itself, every letter about which innumerable tomes have been written, constitutes a hidden temporal, ethical, sonic rhetoric, one that underlies Jewish rhetoric and religion and still informs Jewish teaching and scholarship today. The meaning of the vov of reversal is not without its controversies, of course (cf. Weingreen 1959; Cook 2010; Bamildele 2014). But if we accept vov as a grammatical inflection, the rhetorical effect of all the vovim is to create timelessness, making everything in the Hebrew Bible always present, always sounding, always occurring.

As we have discussed, a “preoriginary obligation” (Davis 2010), the inessential ground of ethical relations for Levinas hints at a prelinguistic and thus perhaps a divine or sacred moral source. And G/d certainly does figure in a lot of Levinas’ work (esp. Levinas 1990a, 1990b, 1998). In this context, the Hebrew letters also can be considered to be “preorginary” (as they are for many orthodox, Chasidic, and other Jews), an infinite but also pre-primordial mystical alphabet out of which writing and speaking a sonic moral space-time is born (see Katz 2003). One does not have to believe in the Hebrew G/d, or even that language is reality, to understand the power of the language, such as sacred pledge of the oath, for example (Agamben 2011). The hidden temporality of the Hebrew alefbet “appears” to be a theory of sonic rhetoric as an orthographic-material reality, one that by its operations and origins is often assumed to be ethical. Is it a sonic rhetorical theory in which language is not only a manifestation of time, but the cause and content of it; a sonic rhetorical theory in which language is a moral reality? קן יְהִי רצון – Ken y’hi ratzon: “May it be so.”

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

Much earlier versions of parts of this essay were presented at the “Roundtable on Rhetorical Temporalities” with Diane Davis, Thomas Rickert, Michelle Ballif, and Daniel Gross, at the Rhetoric Society of America Conference, Minneapolis, MN, 31 May 2018; and at the session “Temporalities in Transition: The Epistemic Music of Rhetoric by Steven B Katz—22 Years Later. An Interview-Performance,” with Mari Ramler, Michael David Measel, and Amy Patterson, at the “Symposium on Sound, Rhetoric, and Writing,” organized by Steph Ceraso, Eric Detweiler, Joel Overall, and Jon Stone at Belmont University, Nashville, TN, and Middle Tennessee State University, Murfreesboro, TN, 7–8 September 2018. The author wishes to thank all these fellow participants and organizers for their formative contribution to his thinking, and others in attendance who offered valuable suggestions. The author wishes to acknowledge in great appreciation the very specific and extremely useful comments of the two anonymous peer reviewers for Humanities, which helped him immensely in revising and (re)focusing this essay. Penultimate but not least, the author gratefully acknowledges the tireless work of Addy Enlow for her earlier help as Research Assistant with the graphics in both presentations, and many other important little matters too numerable to name. Finally, the author (especially and again) wishes to express his sincere gratitude for the generous advice and ongoing assistance of Professor Adam Newton, Special Editor of this issue of Humanities, for his brilliant insight and guidance in bringing this second article to print, and for his continuing support and friendship. Any errors in fact or judgment are mine.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

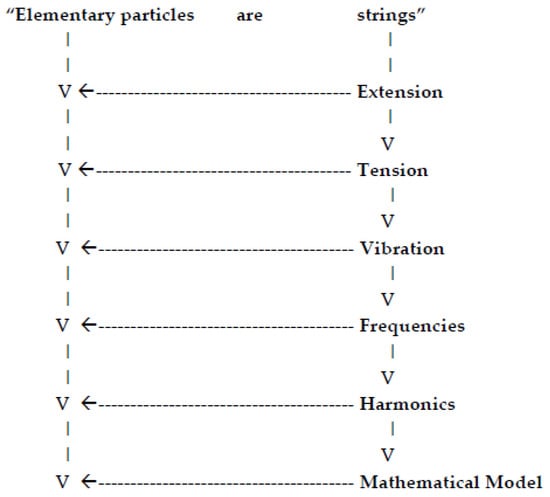

Figure A1.

Metaphor Extension in Superstring Theory.

Superstring Theory attempts to address the problem of “complementarity”—the particle or wave phenomenon, among others—in quantum mechanics (Bohr 2010; Heisenberg 1958). In the ‘metaphorical proposition’ “Elementary particles are strings,” the metaphor of the “string” is used to extend the concept of “elementary particles.” Properties that belong to string are transferred to the concept of elementary particles as a way of understanding and even measuring the particles, and developing Superstring Theory. Because a string has extension, a subatomic particle has extension; because they have extension, they can vibrate; vibration can be measured in frequencies, which can be quantified and mathematical models created, etc. This is only the very beginning of this metaphor, and Superstring Theory. The same question about metaphor extension may apply to sonic rhetorics: Do we ever get out of our metaphorical models, to the “actual” substance/causal structures of the world? (Based on Greene 1986; cf. Boyd 1993; Kuhn 1993).

References

- Agamben, Giorgio. 2011. The Sacrament of Language: An Archeology of the Oath. Translated by Adam Kotsko. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ahern, Katherine Fargo. 2018. The Sounds of Rhetoric, The Rhetoric of Sound: Listening to and Composing the Auditory in Writing. Ph.D. dissertation, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Ahern, Katherine Fargo, and Ashley Rose Mehlenbacher. 2019. Response, Listening to New Voices: Silence, Repair, Hybridity. Edited by David Beard. International Journal of Listening 33: 168–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, Gilbert. 1966. Chironomia or A Treatise on Rhetorical Delivery. Edited by Mary Margaret Robb and Lester Thonssen. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bamildele, Olalekan Olusegun. 2014. The Vav Consecutive and Its Impact on the Tense-Aspect-Mood System of Biblical Hebrew Verb. Ogbomoso: The Nigerian Baptist Theological Seminary, Department of Biblical Studies, Faculty of Theological Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Barad, Karen. 2007. Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett, Scot, and Casey Boyle. 2016. Rhetoric Through Everyday Things. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press. [Google Scholar]

- Birdsall, Carolyn. 2012. Nazi Soundscapes: Sound, Technology, and Space in Germany 1933–1945. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bloom, Harold. 1975. Kabbalah and Criticism. New York: Seabury Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bohr, Niels. 2010. Atomic Physics and Human Knowledge. Mineola: Dover. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd, Richard. 1993. Metaphor and Theory Change: What Is ‘Metaphor’ a Metaphor For? In Metaphor and Thought, 2nd ed. Edited by Andrew Ortony. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 481–532. [Google Scholar]

- Braidotti, Rosa. 2013. The Posthuman. Cambridge: Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bryant, Levi, Nick Srnicek, and Graham Harman, eds. 2011. The Speculative Turn: Continental Materialism and Realism. Melbourne: Repress. [Google Scholar]

- Bulwer, John. 1974. Chirologia: Or the Natural Language of the Hand AND Chironomia: Or the Art of Manual Rhetoric. Edited by James W. Cleary. Southern: Illinois University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Burke, Kenneth. 1952. A Rhetoric of Motives. New York: Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Burke, Kenneth. 1966. Language as Symbolic Action: Essays on Life, Literature, and Method. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Burke, Kenneth. 1969. A Grammar of Motives. Oakland: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Burke, Kenneth. 2007. Essays Toward a Symbolic of Motives, 1950–1955. Edited by William H. Rueckert. Lafayette: Parlor Press, pp. xi–xxi. [Google Scholar]

- Carson, A. D. 2017. Owning my Masters: The Rhetorics of Rhyme and Revolution. Ph.D. dissertation, Clemson University, Clemson, SC, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Cassirer, Ernst. 1955. The Philosophy of Symbolic Forms Vol. 1: Language. Translated by Ralph Manheim. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ceraso, Steph. 2018. Sounding Composition: Multimodal Pedagogies for Embodied Listening. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cicero. 1939. Brutus, Orator. Translated by H. M. Hubbell. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, pp. 306–509. [Google Scholar]

- Cicero, Marcus Tullius. 1942. De Oratore Book III. In De Oratore III, De Fato, Paradoxa Stoicorum, De Partitiones Oratoriae. Translated by H. Rackham. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, pp. 1–185. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, Greg. 2015. Civic Jazz: American Music and Kenneth Burke on the Art of Getting Along. Chicago: Chicago University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, Richard A. 1998. Foreword. In Levinas, Emmanuel, Otherwise Than Being or Beyond Essence. Pittsburgh: Duquesne University Press, pp. xi–xvi. [Google Scholar]

- Comstock, Michelle, and Mary E. Hock. 2016. The Sounds of Climate Change: Sonic Rhetoric in the Anthropocene, the Age of Human Impact. Rhetoric Review 35: 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, John A. 2010. Reconsidering the So-Called Vav Consecutive. Ancient Hebrew Grammar. Available online: ancienthebrewgrammar.files.wordpress.com/2010/05/recvavcons.pdf (accessed on 16 January 2020).

- Croll, Morris W. 1989. Style, Rhetoric, and Rhythm. Edited by J. Max Patrick, Robert O. Evans, John M. Wallace and R. J. Schoeck. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dan, Joseph. 1998. Jewish Mysticism: Late Antiquity. Northvale: Aronson, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Danforth, Courtney S., Kyle D. Stedman, and Michael J. Faris, eds. 2018. Soundwriting Pedagogies. Available online: https://ccdigitalpress.org/book/soundwriting/ (accessed on 5 January 2020).

- Darwin, Charles. 2009. The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals. Edited by Paul Ekman. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, Diane. 2010. Inessential Solidarity: Rhetoric and Foreigner Relations. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press. [Google Scholar]

- De Romilly, Jaqueline. 2013. Magic and Rhetoric in Ancient Greece. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Derrida, Jacques. 1976. Of Grammmatology. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Derrida, Jacques. 1982. White Mythology: Metaphor in the Text of Philosophy. In Margins of Philosophy. Translated by Alan Bass. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, pp. 207–72. [Google Scholar]

- Detweiler, Eric. 2019. Sounding Out the Progymnasmata. Rhetoric Review 38: 205–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbow, Peter. 2006. The Music of Form: Rethinking Organization in Writing. College Composition and Communication 57: 620–66. [Google Scholar]

- Eliot, T. S. 1989. Knowledge and Experience in the Philosophy of F. H. Bradley. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Enos, Richard Leo. 1993. Greek Rhetoric Before Aristotle. Waveland: Prospect Heights. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman, Steve. 2012. Sonic Warfare: Sound, Affect, and the Ecology of Fear (Technologies of Lived Abstraction). Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Greek Word Study Tool. 2019. Perseus Digital Library. Available online: www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/morph?l=perie%2Floi&la=greek&can=perie%2Floi0&prior=tis&d=Perseus:text:1999.01.0177:text=Gorg.:section=502c&i=1#lexicon (accessed on 1 April 2019).

- Greene, Michael. 1986. Superstrings. Scientific American 255: 48–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gries, Laurie, and Collin Gifford Brooke, eds. 2018. Circulation, Writing, and Rhetoric. Logan: Utah State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gries, Laurie. 2019. Editorial Statement. Enculturation: A Journal of Writing and Culture 28. Available online: http://enculturation.net/node/7102 (accessed on 22 January 2020).

- Gunn, Joshua, Greg Goodale, Mirko M. Hall, and Rosa A. Eberly. 2013. Auscultating Again: Rhetoric and Sound Studies. Review Essay. Rhetoric Society Quarterly 43: 475–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handelman, Susan. 1983. The Slayers of Moses. New York: New York Press. [Google Scholar]

- Haralick, Robert M. 1995. The Inner Meaning of the Hebrew Letters. Maryland: Jason Aronson, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Harman, Graham. 2018. Object-Oriented Ontology: A New Theory of Everything. Torrance: Pelican. [Google Scholar]

- Hawhee, Debra. 2009. Moving Bodies: Kenneth Burke at the Edges of Language. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hawhee, Debra. 2013. Bodily Rhetorics: Rhetoric and Athletics in Ancient Greece. Austin: University of Texas Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hawhee, Debra. 2016. Rhetoric in Tooth and Claw: Animals, Language, Sensation. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hawk, Byron. 2018a. Resounding Rhetoric: Composition as Quasi Object. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburg Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hawk, Byron. 2018b. Sound: Resonance as Rhetorical. Rhetoric Society Quarterly 48: 315–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawking, Stephen. 1988. A Brief History of Time: From the Big Bang to Black Holes. New York: Bantam Books. [Google Scholar]

- Haynes, Cynthia. 2016. The Homesick Phonebook: Rhetoric in an Age of Perpetual Conflict. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Heidegger, Martin. 1971a. On the Way to Language. New York: Harper and Row. [Google Scholar]

- Heidegger, Martin. 1971b. Poetry, Language Thought. Translated by Albert Hofstadter. New York: Harper and Row, pp. 91–142. [Google Scholar]

- Heidegger, Martin. 1977. The Question Concerning Technology. In The Question Concerning Technology and Other Essays. Translated by William Lovitt. New York: Harper & Row, pp. 3–35. [Google Scholar]

- Heidegger, Martin. 2010a. Being and Time: A Revised Edition of the Stambaugh Translation. Translated by Joan Stambaugh. Albany: The State University of New York. [Google Scholar]

- Heidegger, Martin. 2010b. Country Path Conversations. Bloomington: Indiana State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Heidegger, Martin. 2014. Hölderlin’s Hymns “Germania” and “the Rhine”. Translated by William McNeill, and Julia Ireland. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Heisenberg, Werner. 1958. Physics and Philosophy: The Revolution in Modern Science. New York: Harper. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes, Steven. 2013. Actants, Agents, and Assemblages: Delivery and Writing in an Age of New Media. Ph.D. dissertation, Clemson University, Clemson, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Hume, David. 1999. An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding: And Other Writings, Independently published.

- Huron, David. 2008. Sweet Anticipation: Music and the Psychology of Expectation. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Katz, Steven B. 1992. The Ethic of Expediency: Classical Rhetoric, Technology, and the Holocaust. College English 54: 255–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, Steven B. 1993. Aristotle’s Rhetoric, Hitler’s Program, and the Ideological Problem of Praxis, Power, and Professional Discourse. Journal of Business and Technical Communication 7: 37–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, Steven B. 1995a. The Epistemology of the Kabbalah: Toward a Jewish Philosophy of Rhetoric. Rhetoric Society Quarterly 25: 107–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, Steven B. 1995b. The Kabbalah as a Theory of Rhetoric: Another Suppressed Epistemology. In Rhetoric, Cultural Studies, and Literacy: Selected Papers from the 1994 Conference of the Rhetoric Society of America. Edited by John Frederick Reynolds. Hillsdale: Erlbaum, pp. 109–17. [Google Scholar]

- Katz, Steven B. 1996. The Epistemic Music of Rhetoric: Toward the Temporal Dimension of Reader Response and Writing. Carbondale: Southern University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Katz, Steven B. 2003. Letter as Essence: The Rhetorical (Im)pulse of the Hebrew Alefbet. The Journal of Communication and Religion 26: 125–60. [Google Scholar]

- Katz, Steven B. 2004. The Alphabet as Ethics: A Rhetorical Basis for Moral Reality in Hebrew Letters. In Rhetorical Democracy: Discursive Practices of Civic Engagement. Edited by Gerard Hauser and Amy Grimm. Hillsdale: Erlbaum, pp. 195–204. [Google Scholar]

- Katz, Steven B. 2009. The Hebrew Bible as Another, Jewish Sophistic: A Genesis of Absence and Desire in Ancient Rhetoric. In Ancient Non-Greek Rhetorics. Edited by Carol Lipson and Roberta A. Binkley. Lafayette: Parlor Press, pp. 125–50. [Google Scholar]

- Katz, Steven B. 2015a. Socrates as Rabbi: The Story of the Aleph and the Alpha in an Information Age. In Jewish Rhetorics: History, Theory, Practice. Edited by Janice Fernheimer and Michael Bernard-Donals. Waltham: Brandeis University Press, pp. 93–111. [Google Scholar]

- Katz, Steven B. 2015b. Burke’s New Body? The Problem of Virtual Material, and Motive, in Object Oriented Philosophy. KB Journal: Journal of the Kenneth Burke Society 11. [Google Scholar]

- Katz, Steven B. 2017. Pentadic Leaves (poem and video of performance). KB Journal 12. Available online: https://kbjournal.org/pentadic-Leaves (accessed on 11 December 2019).

- Katz, Steven B., and Vicki W. Rhodes. 2010. Beyond Ethical Frames of Technical Relations: Digital Being in the Workplace World. In Digital Literacy for Technical Communication: 21st Century Theory and Practice. Edited by Rachel Spilka. London: Routledge, pp. 230–56. [Google Scholar]

- Katz, Steven B., and Nathaniel Rivers. 2017. A Predestination for the Posthumanism. In Ambiguous Bodies: Burke and Posthumanism. Edited by Chris Mays and Nathaniel A. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, pp. 142–61. [Google Scholar]

- Kaye, Deena, and James Lebrecht. 2015. Sound and Music for the Theatre, 4th ed. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kerferd, G. B. 1981. The Sophistic Movement. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn, Thomas S. 1993. Metaphor in Science. In Metaphor and Thought, 2nd ed. Edited by Andrew Ortony. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 533–42. [Google Scholar]

- LaBelle, Brandon. 2018. Sonic Agency: Sound and Emergent Forms of Resistance. Sonics Series (1); London: Goldsmiths Press. [Google Scholar]

- Leff, Michael. 1989. Burke’s Ciceronianism. In The Legacy of Kenneth Burke. Edited by Herbert W. Simons and Trevor Melia. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, pp. 115–27. [Google Scholar]

- Levinas, Emmanuel. 1969. Totality and Infinity. Translated by Alphonso Lingis. Pittsburgh: Duquesne University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Levinas, Emmanuel. 1981. Otherwise than Being, or Beyond Essence. Translated by Alphonso Lingis. Pittsburgh: Duquesne University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Levinas, Emmanuel. 1987. Time and the Other [and Additional Essays]. Pittsburgh: Duquesne University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Levinas, Emmanuel. 1990a. Difficult Freedom: Essays on Judaism. Translated by Sean Hand. Baltimore: The John Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Levinas, Emmanuel. 1990b. Nine Talmudic Readings. Translated by Annette Aronowicz. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Levinas, Emmanuel. 1998. Of the God Who Comes to Mind, 2nd ed. Translated by Bettina Bergo. Standford: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Levinas, Emmanuel. 2000. Entre Nous. Translated by Michael B. Smith. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Levinas, Emmanuel. 2001. Existence and Existents, 2nd ed. Translated by Robert Bernasconi. Pittsburgh: Duquesne University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Measel, Michael David. 2020. Elucidating Attitude in the Keyboard Compositions of Kenneth Burke: Listening for Musical Gestalt and Aural Affect. Ph.D. dissertation, Clemson University, Clemson, SC, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Mendelson, Michael. 1998. The Rhetoric of Embodiment. Rhetoric Society Quarterly 28: 29–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, Leonard B. 1956. Emotion and Meaning in Music. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, Jack. 1995. God: A Biography. New York: Knopf. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, Carolyn R. 1991. Kairos in the Rhetoric of Science. In A Rhetoric of Doing: Essays on Written Discourse in Honor of James L. Kinneavy. Edited by Stephen P. Witte, Neil Nakadate and Roger Cherry. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, pp. 310–27. [Google Scholar]

- Morton, Timothy B. 2009. Ecology without Nature: Rethinking Environmental Aesthetics. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Morton, Timothy B. 2012. The Ecological Thought. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Morton, Timothy B. 2013. Hyperobjects: Philosophy and Ecology after the End of the World (Posthumanities). Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Moses, Myra, and Steven B. Katz. 2006. The Phantom Machine: The Invisible Ideology of Email (A Cultural Critique). In Critical Power Tools: Technical Communication and Cultural Studies. Edited by J. Blake Scott, Bernadette Longo and Katherine V. Willis. New York: The State University of New York, pp. 71–105. [Google Scholar]

- Novak, David, and Matt Sakakeeny, eds. 2015. Keywords in Sound. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Odell, Lee. 1993. Theory and Practice in the Teaching of Writing: Rethinking the Discipline. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ong, Walter. 1958. Ramus, Method, and the Decay of Dialogue. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Osborn, Matthew. 2016. Surprise. Sensibilities, Auralities, and Aesthetics of Rhetorics. Ph.D. dissertation, Clemson University, Clemson, SC, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Overall, Joel. 2017. Kenneth Burke and the Problem of Sonic Identification. Rhetoric Review 36: 232–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, Amy. 2020. Soundscapes for Social Change: Community and Consciousness through Sound Design Rhetorics. Ph.D. dissertation, Clemson University, Clemson, SC, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Perl, Sondra. 1980. Understanding Composing. College Composition and Communication 31: 363–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilsch, Andrew. 2017. Invoking Darkness: Skotison, Scalar Derangement, and Inhuman Rhetoric. Philosophy and Rhetoric 50: 336–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plato. 1961a. Cratylus. In The Collected Dialogues of Plato Including the Letters. Edited by Edith Hamilton and Huntington Cairns. Translated by Benjamin Jowett. Princeton: Princeton University Press, pp. 421–74. [Google Scholar]

- Plato. 1961b. Gorgias. In The Collected Dialogues of Plato Including the Letters. Edited by Edith Hamilton and Huntington Cairns. Princeton: Princeton University Press, pp. 229–307. [Google Scholar]

- Plato. 1961c. Republic. In The Collected Dialogues of Plato Including the Letters. Edited by Edith Hamilton and Huntington Cairns. Translated by Paul Shorey. Princeton: Princeton University Press, pp. 575–844. [Google Scholar]

- Propen, Amy. 2018. Visualizing Posthuman Conservation in the Age of the Anthropocene. Columbus: Ohio State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Quinn, Arthur. 1995. Figures of Speech: Sixty Ways to Turn a Phrase. London: Routledge Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ramus, Peter. 1983. Arguments in Rhetoric Against Quintilian. Edited by James J. Murphy. Translated by Carole Newlands. DeKalb: University of Northern Illinois Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rice, Jeff. 2012. Digital Detroit: Rhetoric and Space in the Age of the Network. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rice, Jenny. 2020. Awful Archives: Conspiracy Theory, Rhetoric, and Acts of Evidence. Columbus: Ohio State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rickert, Thomas. 2005. Language’s Duality and the Rhetorical Problem of Music. In Rhetorical Agendas: Political, Ethical, and Spiritual. Edited by Patricia Bizzell. New York: Lawrence Erlbaum, pp. 157–63. [Google Scholar]

- Rickert, Thomas. 2013. Ambient Rhetoric: The Attunements of Rhetorical Being. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rickert, Thomas. 2016. Rhetorical Prehistory and the Paleolithic. Review of Communication 16: 352–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rickert, Thomas, and Michael Salvo. 2006. The Distributed Gesamptkunstwerk: Sound, Worlding, and New Media Culture. USA Computers and Composition 23: 296–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rueckert, William H. 2007. Introduction. In Essays Toward a Symbolic of Motives, 1950–1955. West Lafayette: Parlor Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sheridan, Thomas. 1968. A Course in the Lectures on Elocution. New York: B. Blom. [Google Scholar]

- Stedman, Kyle D. 2012. Musical Rhetoric and Sonic Composing Processes. Ph.D. dissertation, University of South Florida, Tampa, FL, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Steiner, George. 2013. Grammars of Creation. London: Faber and Faber. [Google Scholar]

- Stephens, Eric James, and Steven B. Katz. 2019. Rhetorics, Ethics, Poetics: A Psychagogic Interview with Dr. Steven B. Katz: On the Occasion of the 25th Anniversary of the Publication of “The Ethic of Expediency: Classical Rhetoric, Technology, and the Holocaust”. Enculturation 28. Available online: http://enculturation.net/Rhetoric_Ethics_Poetics_Katz_Interview (accessed on 16 January 2020).

- Sterne, Jonathan. 2012. The Sound Studies Reader. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Stone, Jonathan W. 2015. Listening to the Sonic Archive: Rhetoric, Representation, and Race in the Lomax Prison Recordings. Enculturation 19. Available online: http://enculturation.net/listening-to-the-sonic-archive (accessed on 16 January 2020).

- Strack, Herman L., and Günter Stemberger. 1996. Introduction to the Talmud and Midrash. Translated by Markus Bockmuehl. Minneapolis: Fortress Press. [Google Scholar]

- Vital, Chayyim. 1999. The Tree of Life: The Palace of Adam Kadmon. Translated by Donald Wilder Menzi, and Zwe Padeh. Northvale: Jason Aronson, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, Jeffrey. 2000. Rhetoric and Poetics in Antiquity. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Weingreen, Jacob. 1959. A Practical Grammar for Classical Hebrew. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Whigham, Peter, ed. 1979. Volume I: The Music of the Troubadours. Santa Barbara: Ross-Erikson. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe, Cary. 2013. What is Posthumanism? Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zuckerkandl, Victor. 1956. Sound and Symbol: Music and the External World. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zylinska, Joanna. 2014. Minimal Ethics for the Anthropocene (Critical Climate Change). Edited by Tom Cohen and Claire Colebrook. Ann Arbor: Open Humanities Press. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | The old Baconian questions and philosophical qualms concerning not only objectivity but whether we ever “get out of” language, bodies, minds, limited senses, human consciousness, have not gone away. The issue of how we perceive (hear), relate to, and know external reality would seem to be particularly important in questions concerning nonlinguistic being and the nonhuman world. This is not the same issue about the relation of posthumanism to humanism (see (Braidotti 2013; Wolfe 2013). Cf. an interesting and sophisticated debate between Richard Boyd (1993) and Thomas Kuhn (1993) about the role of metaphor in the construction of scientific fields, and whether or not metaphors in science lead researchers out to causal structures of the physical world [see Appendix A]). The issue is ontological as well as epistemological. The as is about the undeniable fact that at different levels we (and other things too) are constituted in relatively stable bodies and minds (more on this below), from which we perceive and “know.” As the Copenhagen School of quantum mechanics was good at pointing out, despite technological development, our limitations as human beings persist, and the ‘human variable’ may always have to factor into any probability equation (Heisenberg 1958; Bohr 2010; cf. Katz 1996). Despite Entanglement Theory in new materialism, and a corresponding “demoting” of the power of language (see Barad 2007, esp. chp. 7), most of our thinking and discussion about sonic rhetorics take place in language (the echo of the origin of the (re)sound is located in the ear, depending for its mediation in the limited human sense of hearing). We may need to (re)remember that almost everything we do as humans is in and through the agency of language as “symbolic action” (see (Burke 1952, 1966, 1969; cf. LaBelle 2018); see Katz (2015b); Katz and Rivers (2017) for a more nuanced discussion of Burke in relation to posthumanism). The question of how humans know is a decidedly postmodern one, focused as it is back on the human and on language—a take with which most scholars in sonic rhetorics today would probably take umbrage. But to some degree, on what I call ‘the spectrum of linguistic determinacy’, language influence thought, from a little to a lot. Derrida (1982) asserted that all philosophy is metaphor, and even Heidegger focused in on the role of language (Heidegger 2010b), sound in language (Heidegger 1971a), and poetry itself (Heidegger 1971b, 2014) in the construction of his philosophy of Being (Heidegger 2010a). A couple of related issues are pertinent to the study of sound and ethics, the purview of this essay. First, one is somewhat pressed to find discussions of sound as or in relation to ideology, such as the uses of sonic rhetorics for propaganda purposes, past, present, or future (cf. Birdsall 2012; Goodman 2012; Haynes 2016; LaBelle 2018). Second, one is seemingly less hard-pressed to find discussion of sound in relation to an ethical consideration of phronesis, or “ends.” Scholarship concerned with teaching seems to consider ethics more (although that is a generalization [see Morton, passim]). One suspects that the ideology of sound, like sound itself, are assumed to be “natural,” and thus “neutral” if not “wholesome,” and therefore are already and always good. How much of “the value” of sound as pedagogy and praxis is driven by “naturalism,” “metaphysical empiricism,” or “technological imperatives”? In the past I have argued that even “social-epistemic” rhetoric is not ideologically neutral or necessarily good (Katz 1992, 1993; cf. Moses and Katz 2006; Katz and Rhodes 2010); the same may be said about sonic rhetorics. A wonderful new proclivity in sound studies is to regard ideology and ethics as questions of “access” and “circulation”—“praxis”—in advocating and using sound to teach environmental awareness, social justice, and equality (e.g., Ceraso 2018; Danforth et al. 2018; Gries and Brooke 2018; Hawk 2018a). Elenchi. Should we inquire about phronesis (ends) as well as praxis (means)? Can we keep sonic issues from being about technological values only, the way Hawk (2018b), or Ahern and Mehlenbacher (2019) do? Should we question phronesis itself? And what about our belief that we can overcome any perceived “deficiencies” of human bodies by medical/pharmaceutical means, genetical manipulation, or prosthetic enhancements? I am not talking about “Ableism” here, but existential election: the point at which the ‘healthy’ posthuman morphs into transhuman, with its new attendant ontological, epistemological, and physical alterations and commitments, none of which are ideologically or ethically neutral. Further, how much is the absence/presence of ideology/ethics in sonic rhetorics connected to if not the result of the dismissal of language (“the nonlinguistic turn”) and a decentering of the human (the “nonhuman-turn”). I see some danger here, but also justifications and value: sonic rhetorics are rightly focused on ecology—not only on acoustic ecology, but on damaged ecology—on the polluted environment, on human-made global warming, and on violent climate change in the Anthropocene (see Comstock and Hock 2016; Morton 2009; Pilsch 2017; Propen 2018; Zylinska 2014). Even when the study of the human and language is precluded, these scholars/studies rightly see sound studies as a way of enhancing our awareness of the nonhuman physical world and our effects on it through increased attention to sound. But even though we may be “entangled” with all living and nonliving things, we are still constituted at several levels of physicality, with bodily awareness and consciousness. Even though we are also part of the random flux, we are beings who mostly use language to negotiate and reconstruct the material world (Burke, passim; cf. Katz and Rivers 2017). So when we develop theories, are we merely extending metaphors (whether “active” or “passive” epistemic access [Boyd 1993; see Appendix A])? As I have asked before, can we continue to develop indeterminate methods to work with sound as well as affect (Katz 1996; cf. Katz 2015a)? Can we transcend current human consciousness (Katz 2015b, 2017; Katz and Rhodes 2010; Katz and Rivers 2017)? |

| 2 | How do we research and talk about time without destroying it by our literary and rhetorical methods of analysis and practice, which seem to always remain grounded in Newtonian space-time modes of consciousness, just as New Physics is? (Katz 1996, 2015b). In keeping with both Heidegger and Levinas, I would say that the first ethical action that sound (whether natural, voice, musical instruments, machines, writing) demands of us as conscious beings is the imperative to listen attentively, to really hear, to respond in kind, to perform, to practice in life. One answer to the question how to avoid destroying time (and affect) with our methods is to ground our methods in poetry (Heidegger 1971b, 2010b, 2014), although in terms of ethics and essence I think that Levinas as well reveals the paradoxicality of this proposition (e.g., Levinas 1981). |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).