Abstract

The pirate tropes that pervade popular culture today can be traced in large part to Robert Louis Stevenson’s 1883 novel, Treasure Island. However, it is the novel’s afterlife on film that has generated fictional pirates as we now understand them. By tracing the transformation of the author’s pirate captain, Long John Silver, from N. C. Wyeth’s illustrations (1911) through the cinematic performances of Wallace Beery (1934) and Robert Newton (1950), this paper demonstrates that the films have created a quintessentially “American pirate”—a figure that has necessarily evolved in response to differences in medium, the performances of the leading actors, and filmgoers’ expectations. Comparing depictions of Silver’s dress, physique, and speech patterns, his role vis-à-vis Jim Hawkins, each adaptation’s narrative point of view, and Silver’s departure at the end of the films reveals that while the Silver of the silver screen may appear to represent a significant departure from the text, he embodies a nuanced reworking of and testament to the author’s original.

1. Introduction

Piracy has shaped modern America. Four hundred years ago, in late August 1619, the privateer ship White Lion sold several captive Africans from Angola into servitude to the fledgling English colony of Virginia (). The White Lion was one of two privateers working on behalf of the British government to attack the Portuguese slave ships transporting kidnapped Africans to their plantations in South America; in doing so, and then in transporting these people into English territories, the pirates brought about the North American slave trade. In other words, one of American history’s great crimes, slavery, was initiated by another, piracy. Neither of these horrifying industries should have become entertaining tropes in popular culture, yet the pirate figure is part of the fabric of popular literature and visual culture, particularly television and film. This disparity is satirically skewered by South Park in season 13, episode 7, in which the boys use their parents’ credit cards to play pirates in a place they had heard was rife with piracy, Somalia (). The episode neatly juxtaposes the children’s ludicrous conception with the very real horrors of twenty-first-century piracy off the east coast of Africa. Piratic tropes in popular culture are nothing new—they have existed for centuries—but cinematic tropes of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries can be traced in large part back to the critical and popular success of Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island (1883).1 The story, like the writer, is British but was quickly appropriated by the burgeoning American market for illustration and then cinema. The purpose of this paper is to determine how American media influenced popular culture representations of piracy by tracing the evolution of Stevenson’s pirates through early twentieth-century illustrations and film.

Treasure Island crystallized some of the attributes of piracy within popular culture with such success that they are constantly recycled and referenced in different forms in different genres. Many of these attributes, while distilled by Stevenson, made their way into popular culture through American illustrations and cinematic renditions of his novel, creating, in essence, an “American pirate.” This lens helps to place our analysis within the context of trans-Atlantic literary studies and contributes to the understanding of ways in which Victorian literature was adopted into American media. For the purposes of this paper, we will limit our scope to three especially popular and influential adaptations: N. C. Wyeth’s illustrations for the 1911 Scribner’s edition of the novel and two specific film adaptations. Richard Dury lists ten film adaptations of Treasure Island up to 1950, but we wish to focus our discussion on the following: The first is the 1934 MGM film, the first “talkie” adaptation of the story, starring Jackie Cooper as Jim Hawkins and Wallace Beery as Long John Silver and directed by Victor Fleming. Fleming would go on to direct The Wizard of Oz (1939) and Gone with the Wind (1939), and his skill is evident in the direction of Stevenson’s tale. The second is Disney’s 1950 film, starring Bobby Driscoll as Jim and Robert Newton as Silver, which was Disney’s first full-color live-action movie; this film is iconic, setting the standard for modern pirate tropes in popular culture, but owes debts to the earlier film, particularly in its characterization of Silver and the other pirates. Consequently, our focus is Silver and how he is morphed by film into a new character trope.

Stevenson bases his pirates on personal friends and historical sources, depicts them as thoroughly British, and uses scant but vivid visual details to differentiate these villains.2 In addition, he constructs the pirates through two retrospective points of view: the wiser, older Jim recalling his adventure and Dr. Livesey filling in where Jim is separated from his party. As a result, Silver, unforgettable as he is, is not the protagonist. Stevenson also uses these narrative perspectives to add irony that, while at times amusing, amplifies the danger in which Jim and his comrades find themselves. These qualities of character and perspective, as well as costume, are just a few elements that distinguish Stevenson’s pirates as his own; the alterations to these details through illustrations and film exemplify the Americanization of Stevenson’s pirates, especially where Silver is concerned. Following an analysis of Stevenson’s Silver, we consider costumes in Wyeth’s illustrations, then analyze character in Fleming’s 1934 MGM film, and conclude with perspective in Haskin’s 1950 Disney film—though all characteristics play a role in each section.

Analyzed together, the adaptations demonstrate that while illustration and film have reduced Stevenson’s pirates to the status of clichés in popular culture, these “American” pirates are no less complex than Stevenson’s originals. Our discussion will avoid value judgements of the adaptations, which have been offered elsewhere, not least by Scott Allen Nollen in Robert Louis Stevenson: Life, Literature and the Silver Screen (1994). Nollen’s book, while a valuable record of Stevenson-inspired films, judges the film adaptations of Treasure Island against the merits of Stevenson’s text. We instead analyze the ways in which film adaptations necessarily alter and mutate the novel into something different, not supplanting the text but rather supplementing and augmenting it for new media and new audiences. The illustrations and films remove or minimize certain qualities and emphasize others and, in doing so, contribute to modern pirate tropes. Ultimately, these Americanized pirates are figures that coexist alongside the author’s originals, but whereas Stevenson’s buccaneers may be less familiar to the general public (depending on readers’ direct exposure to his text), Wyeth’s, Fleming’s, and Haskin’s versions endure—not always as distinct characters but as images, gestures, jokes, and even vocalizations, thanks to their influence on myriad forms of entertainment, from South Park episodes to the Pirates of the Caribbean franchise to memes and “Talk Like a Pirate” days.

2. Stevenson’s Long John Silver: Creating a Monster

Long John Silver, as with so many of Stevenson’s characters, is based on meticulous research that enhances the villainy of his pirate captain.3 One historical model for Silver, we contend, is Captain Charles Johnson’s Edward Teach, or the notorious Blackbeard, as portrayed in A General History of the Robberies and Murders of the Most Notorious Pirates, published in 1724. We know from Stevenson’s essay “My First Book” (), as well as from his use of the name “Israel Hands,” that he used Johnson as a source for Treasure Island. The key here is that Teach, although mediated through the voice of Johnson, was a very real person, guilty of horrific crimes against humanity. Appropriately read, we can identify Teach in Silver, a character genuinely to be dreaded. The narrative builds to the parallels between Teach and Silver through Jim’s introduction to the novel’s other pirates, as well as through their impressions of Silver. In a manner that anticipates Joseph Conrad’s Kurtz in The Heart of Darkness (1899), Silver’s reputation precedes him, and it is terrifying. As the story opens, Jim first meets Billy Bones, then Black Dog, then Blind Pew—each in scenarios more nightmarish than the last. However, none compare to the “seafaring man with one leg” whom Bones himself fears (). Transfixed by Bones’ stories, Jim shares in his terror, though he does not yet know Silver by name: “How that personage haunted my dreams, I need scarcely tell you” (ibid., p. 48). Even Silver’s whimsical parrot indicates Silver’s superiority to his companions, while also testifying to Stevenson’s playful appropriation of historical sources. As Jim, Dr. Livesey, and Squire Trelawney discover the significance of the map, the squire exclaims of Flint, “[h]eard of him, you say! He was the bloodthirstiest buccaneer that sailed. Blackbeard was a child to Flint” (ibid., p. 75). Silver—having reduced an infamous pirate to the namesake for his pet, a foulmouthed bird—has outdone both this fictional predecessor and, if we can trust Trelawney’s estimation, his historical one.

Johnson informs us that part of what made Teach dangerous was his gift for smooth-talking and largess:

Similarly, when Jim meets Silver, he seems almost entirely benign: “Indeed, he seemed in the most cheerful spirits, whistling as he moved about among the tables, with a merry word or a slap on the shoulder for the more favoured of his guests” ().4 Silver’s generosity and charisma recall Johnson’s description of Teach’s cordiality. Both Teach and Silver share an ability to manipulate dangerous people through charm, intelligence, and strategy.5Captain Teach, alias Blackbeard, passed three or four months in the river [in North Carolina], sometimes lying at anchor in the coves, at other times sailing from one inlet to another, trading with such sloops as he met for the plunder he had taken, and would often give them presents for stores and provisions took from them; that is, when he happened to be in a giving humour.()

Of course, Teach was also capable of both calculated and random brutality, such as shooting one of his crew, the very real pirate Israel Hands, in the knee and maiming him for life. Likewise, Silver stands apart for the coolness with which he could speak about murder or commit the deed. One example is when Jim, hidden within an apple barrel in chapter 11, overhears Silver’s plot to steal the treasure and murder Jim and his friends. Another is provided by the horror of Silver enacting these plans and murdering one of the crew, “Tom,” in chapter 13. The way it is accomplished speaks to Silver’s violence and agility. Tom tells Silver, “you’re old, and you’re honest” (). Tom has been misled by Silver on both accounts because Silver is certainly not honest, and the manner in which Silver murders him speaks to a youthful force and cold-blooded intent. Having already broken Tom’s back by hurling his crutch like a javelin, he “was on the top of him next moment, and had twice buried his knife up to the hilt in that defenseless body” (ibid., p. 119). This act defines Silver for the reader; it is difficult to move beyond this moment.

Overhearing Silver’s plans and witnessing Tom’s murder present crucial moments for Jim in his relationship with Silver. Both scenes confirm Silver’s ruthlessness, correct Jim’s misconceptions of Silver as a friend, and call attention to perspective in establishing Silver’s monstrosity. They also highlight Jim’s differing relationships with Silver, which Jim and Dr. Livesey have established by narrating the tale retrospectively. When Jim meets Silver at the Spyglass in chapter 8, he presents us with two points of view and introduces these competing relationships: that of his younger child-self encountering the affable sea-cook for the first time and that of the young adult who has now survived to tell the tale, enlightened about his foe’s character. The perspectives through which Jim and his readers are introduced to Silver—from Bones’ tales to comparisons with crewmates and allusions to historical figures—have several effects on how Stevenson’s token pirate is constructed for the reader. Bones’ warnings about the one-legged sailor, Black Dog’s presence in Silver’s pub, and Silver’s aptly named parrot number among the many clues that indicate Silver’s true identity, but Jim and his compatriots remain blind until Jim, hidden within the apple barrel, overhears Silver plotting murder and, soon after, witnesses Silver’s brutal attack on Tom. Both scenes are jarring, for Jim and readers. Jim is awakened from his childish naivety and admits to, now, developing “a horror of his cruelty, duplicity, and power” (ibid., p. 108). For savvy readers, these events simply confirm Silver’s identity as a pirate—an unsurprising revelation that Jim the narrator has been building to through so many obvious clues. However, Jim’s reflection on his awakening also develops Silver’s villainy; that Jim was so surprised by what he learned reminds us of his status within the narrative and that a criminal has been grooming a child.

The very real danger of this diegesis is emphasized further by the actions of Israel Hands. Unlike Silver, who continues to manipulate those around him, despite being revealed as a pirate, Hands is a monster without a mask. In chapter 23, Jim witnesses a drunken fight between Hands and his shipmate, which ends lethally; in chapter 26, Hands turns his murderous attentions to Jim. Stevenson conjures a potential child murderer, fueled by alcohol, who nearly achieves his objective. It should not be lost on the perceptive reader that a grown, drunk, violent man chases a young boy up the rigging with a dagger; in fact, Jim is horribly wounded by that dagger, even as he defends himself. Hands is terrifying, but Silver must be more so to keep such a character in check, and in this sense, Hands becomes a crucial narrative device to help the reader gauge the danger posed by Silver.

The comparisons between pirates and the multiple perspectives of Silver, together with Stevenson’s historical research, establish Silver as one in a vivid cast of characters. However, Jim’s status as the principal narrator solidifies his role as the protagonist, and it is his relationship with Silver that drives the plot. Silver may sail into the distance, but the story concludes with what Jim hears and sees. Moreover, Silver is, obviously, a villain. Though scintillating and charming, his actions and intentions are unmistakably malicious. Stevenson brings humor to this Silver through sarcasm and irony, but the story is not a comedy, and Jim concludes undeceived and glad to be separated from “[t]hat formidable seafaring man with one leg” (ibid., p. 223). In Stevenson’s world, the pirates are fascinating and larger-than-life but ultimately life-threatening, much like their real-world counterparts.

These are the characteristics that the films subvert. However, film was not the first medium to adapt Treasure Island pictorially. There were, as Dury and Nollen have thoroughly documented, many theatrical productions of the novel, but more importantly for our discussion, Treasure Island was heavily illustrated as a novel beginning in 1885. The first book illustrations were produced in France by the artist George Roux, an erstwhile illustrator of the novels of Jules Verne. Stevenson himself viewed and generally approved of these illustrations, as Kevin Carpenter has established by unearthing and publishing a review Stevenson wrote (unpublished during his lifetime).6 Another famous suite of illustrations was produced in 1899 by Walter Paget for a Cassell edition of the novel. However, the most important illustrations were produced in America in 1911, by the artist N. C. Wyeth (1882–1945). Wyeth’s have become the iconic images that have visually defined Treasure Island for generations of readers; they have also influenced the aesthetic rendering of the novel in film, performing as a conduit between the novel and its early cinematic adaptations. As we will demonstrate, Wyeth’s aesthetic informed the first “talkie” film of Treasure Island, although an analysis of these images also demonstrates how film, by the nature of the medium, alters Silver’s character into something new for an American cinema audience.

3. Illustration and the Modern Pirate

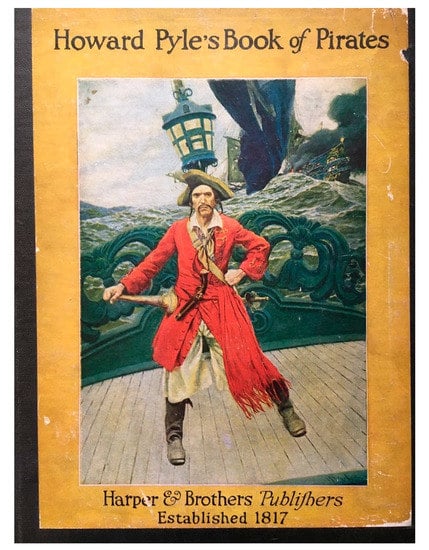

The American artist, writer, and illustrator Howard Pyle (1853–1911) is, arguably, the twentieth century’s most influential illustrator of pirates. Pyle was instrumental in establishing the first American school of illustration at what is now known as the Brandywine School of Illustrators; he was responsible for protégés such as Wyeth, Norman Rockwell, and Maxfield Parrish. To a modern eye, Pyle’s illustrations look proto-cinematic and for good reason. Jill P. and Robert E. May note that the 2006 Disney film Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man’s Chest, the second installment of the franchise, was directly inspired by the posthumously published Howard Pyle’s Book of Pirates (); the pirates in Pirates of the Caribbean appear to be lifted from Pyle’s pages (). They also observe that this same book had influenced the 1926 film The Black Pirate, starring Douglas Fairbanks, and the 1935 film Captain Blood, starring Errol Flynn (ibid, p. 201). May and May make the obvious connection: Pyle’s influence, whether direct or indirect, never left the cinema. These early movies inscribed the aesthetic of the eighteenth-century pirate into popular culture, creating a visual discourse that was borrowed, developed, or pirated by subsequent production companies, including Disney.

Pyle’s pirates are dramatically dressed, either moving fluidly in fight scenes or standing stoically while the ocean swirls around them. His pirate captain, pictured on the cover of his Book of Pirates (see Figure 1), is a case in point: he wears a long, flowing coat and baggy trousers, bearing little relation to the illustrations of Captain Johnson’s accounts. Pyle’s captain is, however, dramatic, forceful, and full of movement—aspects of Pyle’s works that pervade the aesthetic of early cinema.7 This movement is also evident in the work of his mentee, Wyeth (1882–1945), yet Wyeth’s pirates for the 1911 Scribner’s edition of Treasure Island are also thoroughly his own.8 Wyeth departs from Pyle’s tropes by paying close attention to Stevenson’s text, while also applying Pyle’s dynamic movement and dramatic mise-en-scene to Stevenson’s closely observed characters and settings.

Figure 1.

Cover for Howard Pyle’s Book of Pirates (). From Richard J. Hill’s collection.

Wyeth’s rendering of Stevenson’s text immediately influenced early cinematic adaptations. Dury’s filmography of Stevenson’s works lists a 1920 film, directed by Maurice Tourneur and starring Charles Ogle (Silver), Shirley Mason (Jim), and Lon Chaney (Pew/Merry), that is directly informed by Wyeth’s pictures; no imprint of the film survives, but there are still images that confirm the aesthetic debt. Fleming’s 1934 film, the first “talkie” adaptation of the novel, is also indebted to Wyeth’s visual interpretations in many of the corresponding scenes. The first narrative illustration, “Captain Bill Bones,” for example, is of Bones on the clifftop, telescope in hand, watching for the one-legged man (). Part of the dynamism of the image is provided by the strong wind billowing his dark great coat in what appears to be a rainstorm, in a style reminiscent of Pyle’s “Captain” (Figure 1). Wyeth’s illustration seems to resonate with the first appearance of Bones in Fleming’s film (); while not on top of a cliff, Bones appears at the door of the Admiral Benbow, and as the door opens, a gust of wind catches Bones’ coat in a similar fashion, with the wind and the rain following him as a metaphor for the trouble that is pursuing him. The aesthetic is similar, as is Bones’ costume; however, there is also a thematic debt of foreshadowing that Fleming seems to have borrowed from Wyeth.9

Other remarkable parallels between Wyeth’s pictures and Fleming’s film exist. Blind Pew struggling in the dark, cane in hand, before he is run over, though not identical (he is killed by a carriage in the film, rather than the horse of the text), clearly bears debts to Wyeth; his costume again is very similar (; ). Captain Smollett raising the Union Jack, in defiance of Silver, appears to bring Wyeth’s illustration of the same scene to life (; ). The storming of the stockade by Silver’s crew is equally close in construction and even perspective, as we watch the pirates, in both images, pour over pikes and run at us (; ). Indeed, Fleming seems to give movement to the claustrophobic sense of impending violence: in Wyeth’s illustration, the pirates are close upon us, pistols in hand, daggers in teeth, and Fleming’s moving pictures show exactly how close to the barracks they really are, as Jim, Captain Smollett, and the squire fire out of the windows at close range (1:06:36–07:24).

However, Fleming’s film departs from Wyeth’s vision in one important aspect: the depiction of Silver. This is where a comparison of Wyeth’s illustrations—which form the visual framework for so many subsequent adaptations—against our two film examples is most instructive because it becomes clear how American cinema creates a new variation of the character. Wyeth’s Silver is younger, more powerful in build, physically menacing, and therefore much closer to Stevenson’s own invention. Physical descriptions of Silver in the text are minimal, yet they provide a memorable image, beginning with Jim’s first impressions:

These general characteristics are repeated often: Silver is almost always portrayed as impressively nimble and powerful, easily identifiable by both his amputation and his parrot, and noteworthy for his ability to almost always behave cheerfully and with poise, no matter how angry or duplicitous. Using textual impressions provided by Stevenson, Wyeth has created a Silver for the reader to fear. In the first instance—“Long John Silver and Hawkins” for chapter 10 ()—illustrating Jim’s interaction with Silver in the Hispaniola’s galley prior to Silver’s mutiny, Silver watches Jim, his brow shaded, pipe in a powerful hand, as Jim gazes at the parrot Flint. We as the reader/viewer can believe that this Silver would be physically and morally capable of murder and of deception.As I was waiting, a man came out of a side room, and, at a glance, I was sure he must be Long John. His left leg was cut off close by the hip, and under the left shoulder he carried a crutch, which he managed with wonderful dexterity, hopping about upon it like a bird. He was very tall and strong, with a face as big as a ham—plain and pale, but intelligent and smiling.()

Stevenson insisted that his illustrators capture his characters (), which was often difficult, given that the text provides so little visual information. Stevenson was an exacting taskmaster of illustrators. He wrote much about the art of illustration, including about Roux’s work for the first illustrated book edition of Treasure Island. Stevenson’s initial reaction to Roux’s illustrations was ecstatic, as he writes to his father on 28 October 1885 that the

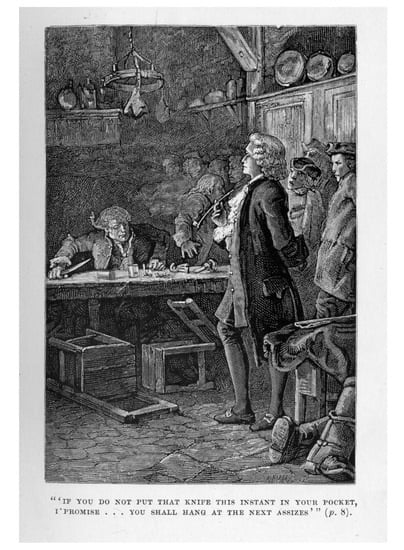

His later review, written probably in late 1884 or early 1885, was more circumspect, however. Referring to Roux’s illustration of Dr. Livesey (see Figure 2) confronting Billy Bones at the Admiral Benbow, Stevenson writes that it is “lacking in construction, accuracy and dramatic fitness. Had the doctor so stood, he would never have lived to swim in the Hispaniola or dispense quinine to Mr Merry” (). As with Silver, the text gives up very little information about how the doctor should look: “I remember observing the contrast the neat, bright doctor, with his powder as white as snow, and his bright, black eyes and pleasant manners, made with the coltish country folk” (). Stevenson’s criticism refers to the doctor’s perceived age and stature in the illustration, which appears to depict an older, patrician gentleman, who, the author argues, would not be physically capable of performing the acts he achieves in the text.artist has got his types up in Hogarth; he is full of fire and spirit, can draw and can compose, and has understood the book as I meant it, all but one or two little accidents, such as making the Hispaniola a brig. I would send you my copy, but I cannot; it is my new toy, and I cannot divorce myself from this enjoyment.()

Figure 2.

George Roux, “If you do not put that knife this instant in your pocket, I promise … you shall hang at the next assizes” (). From Richard J. Hill’s collection.

Stevenson’s critique of Roux’s Dr. Livesey is instructive in allowing us to examine how effective Wyeth’s illustrations are in visualizing the narrative as Stevenson would have wanted. If we apply this critical framework to Silver, it becomes clear that Wyeth has, unlike Roux, closely read the character and how his physicality works within the context of the narrative. Wyeth’s Silver is strong and nimble, and in the illustration “To me he was unweariedly kind” (), his position and posture—though shadows are cast across his face so you cannot read or see it, he is clearly looking up at Jim under his brow—represent his strength and hint at his duplicity as he watches and assesses his prey. Jim, by contrast, is physically fragile but strikes a bold pose, hands on hips, in the stance of the classical hero. Jim is presented as both courageous and vulnerable, and the movement of the ship rocks Jim away from Silver, as if to indicate that they are pulling in different directions. More significantly, the composition of their physical postures foreshadows the later illustration, “For all the world, I was led like a dancing bear” for chapter 21 (), in which Silver drags a resistant Jim on a leash towards the final resting place of the treasure. Silver here is powerful, inexorable; as Wyeth’s biographer David Michaelis points out, “Silver is … strong enough to hold Jim in one powerful fist. As they climb to the treasure cave, Silver’s single good leg is exaggerated and out of step with the figures marching up the hill” (). Now the two characters are literally pulling in opposite directions, and Jim’s gaze is, again, fixed on the parrot, Captain Flint, perched on Silver’s shoulder. The first image hints at Silver’s treachery and violence; the latter realizes it, with some horror.

4. The Trick of Perspective

Silver’s savagery, and his true criminal nature, as created by Stevenson and rendered by Wyeth, is where, we argue, the American cinematic adaptations of Long John Silver bifurcate: whereas Wyeth’s depiction of Silver is consistent with the text, the films alter him. The trick of Stevenson’s narrative is to provide a first-person perspective from a boy who does not quite intuit or fully understand the threats around him. Except for the chapters narrated by Dr. Livesey, Silver is mediated through Jim’s developing personality in a first-person narrative. Perceptive readers are forced to read between the lines to understand what Silver and his confederates might be saying, doing, or plotting behind Jim’s back. This technique allows Stevenson to construct a story that can be read by children and adults in very different ways. However, this narrative technique is much more difficult to reproduce onscreen for a simple reason: we no longer look through Jim’s eyes, but now look at Jim and everything that goes on around him. Our two examples encapsulate the way film—by necessity of the camera’s gaze—inherently alters the characterization of Silver, creating a new pirate captain for the cinema age. The camera provides a third-person perspective of the action and the characters. Instead of seeing the world through Jim, the viewer becomes a detached witness to both Jim and his surroundings, including, importantly, Silver. Where Stevenson forces the reader to perceive and interpret events through Jim’s gaze, on screen, we now get to observe Silver manipulating Jim behind his back and the pirates behaving according to Silver’s guidance. The effect is that the audience watches Silver. The cinematic Silver, rather than replacing or usurping Stevenson’s original, is an original himself, created out of the technical demands of the cinematic medium and the need to satisfy audiences of early to mid-twentieth-century America. Beery’s and Newton’s performances play to this advantage, and the effect is comedic. We follow Silver’s gaze and are eavesdroppers on his dealings when Jim is not present. This leaves a film director with a problem of character: if the viewer is privileged in seeing the “real” Silver, then that Silver cannot be too unsympathetic. Stevenson’s Silver, as discussed, is anything but sympathetic, so the filmmakers and actors must find ways to soften the character while maintaining the essence of the plot. We argue that this is achieved through casting, changes in plot, and the reduction of Jim’s role from proactive to passive within the story.

5. Casting Long John Silver

Dury’s filmography lists the various castings of Silver over the last 100 years: in addition to Beery and Newton, Dury lists Ben F. Wilson (1912), Violet Radcliffe (1918), Charles Ogle (1920), Hugh Griffith (1960), Orson Welles (1972), Kirk Douglas (1973), Brian Blessed (1985), Jack Palance (1998), and Eddie Izzard (2012), among others, as playing Silver (). This is a stellar array of talent playing one role; however, each of these actors, at the times they made their respective films, were physically inconsistent with the powerful, athletic, “monkey”-like Silver in Stevenson’s text () or in Wyeth’s illustrations. Using our two primary examples—Wallace Beery (1934) and Robert Newton (1950)—as emblematic of the whole compared with Wyeth’s imagery and Stevenson’s textual description, the actors hired to portray Silver are most often too old and physically disadvantaged to be able to perform some of the actions of the text’s Silver.

One obvious obstacle to physical authenticity is Silver’s leg: cut “close by the hip” in the text, all the actors to play him are bipedal; therefore, they all had to fold and secure their left legs in what must presumably be a very uncomfortable position, making the role physically challenging (). Such an arrangement must also make moving like Stevenson’s Silver very difficult. Fleming accounts for this by using an action double for Beery, most clearly in his murder of Tom, allowing the audience to believe in his physical prowess (). Newton maneuvers impressively on the crutch but does little to convince the viewer of any physical threat. This fact allows for film adaptations to further soften the Silver character as we will discuss in the next two sections: where Stevenson’s Silver appears to use his disfigurement to disguise his physical abilities, making him dangerous, film adaptations often use it to blunt any real threat. Charlton Heston, for example, is a menacing presence in the 1990 Turner Pictures adaptation, but his age and awkwardness of movement are a clear contrast with Wyeth’s dynamic, nimble Silver. With the possible exception of Tim Curry—who is younger and more agile than his cinematic counterparts—in the playful 1996 film Muppet Treasure Island, the Silver of the screen must rely more on his wits, his charm, and his presence of character, than on any physical threat he poses, in order to manipulate his crew, Jim, or Jim’s friends.

6. MGM’s 1934 Treasure Island: Tears and Happy Endings

Wallace Beery must be given his due credit for establishing some of the acting techniques that have been clearly used (whether consciously or not) by subsequent pirate-captain actors. Beery’s Silver is the first “talking” version of the character, and therefore, Beery, director Victor Fleming, and screenwriter John Lee Mahin helped to create the manner in which Silver could be softened, even sanitized, to suit the sensibilities of a 1930s American cinema audience. Fleming’s black-and-white adaptation is remarkably loyal to the narrative complexity of its source material, except when it comes to Silver, who is forced into a different narrative role. In order to sell the movie to a mass audience, Silver’s likeability must be established through the skill of the actor, which is why the role has attracted some of the great male actors of the twentieth century. The actor is tasked with selling Silver’s duplicity and ruthlessness, while simultaneously making him appealing. Beery manages this through comic timing and facial expression, inviting the audience into his schemes. The camera follows him, for example, away from Jim as we listen to him conspire with his crew, before and after the apple barrel scene (). This comic role becomes immediately obvious when we first enter Silver’s inn (ibid., 28:53–32:42). Instead of raising his voice, Beery’s Silver escorts Jim in from outside, sounding a warning whistle before he does so. The audience gets to witness the bawdy pirates humorously organizing themselves into some civility in order to fool Jim. Once in the tavern, the narrative departure from the novel is immediately clear: the third-person camera perspective looks at Jim, with Silver over his shoulder. No longer do we see Silver through Jim’s eyes; we now watch him closely as he winks, scowls, and cajoles his pirate crew through the charade. The effect is deliberately comic. We laugh at his audacity and cunning, and Beery’s performance invites the viewers to enjoy his trickery; we, the audience, become his conspirators, and the movie becomes Silver’s story, as much as Jim’s. Beery still imbues his character with violence and ruthlessness, but the comic distancing allows the audience to root for him. He becomes a picaresque rogue, more in the tradition of Dickens’s Fagin from Oliver Twist.

However, the key to cementing Silver’s appeal is the ending of the film. According to a Turner Classic Movies article by Bill Goodman,

What did Mayer expect from a happy ending? The movie concludes with Silver persuading a crying Jim to let him out of his cage, in order to escape the horrors of hanging from the yardarm (which he gleefully describes), but not before Jim makes him promise not to steal any of the treasure (). Silver has already broken this promise, dropping a bag of gold at Jim’s feet; nonetheless, after neutralizing Ben Gunn with a comical blow to the head (so it is Jim, not Gunn, who aids him), Silver lowers the rowboat and, smiling and waving to Jim and the audience, escapes into the darkness. The happy ending is the loveable Silver reconciling with Jim and escaping with what we presume is a small share of the treasure. Beery’s trick is to make us cheer for the pirate, despite his actions throughout the story; this trick marks the American appropriation of the pirate figure from Stevenson’s tale, transmuting him from a dangerous villain, entrenched in historical research and the cruel realities of violence and crime, to a rogue and a rebel, defining his own fate and resisting the hierarchical authority of British rule.10Having never read the book or the shooting script, [MGM cofounder Louis B.] Mayer was distressed at the lack of a happy ending. To make matters worse, there was no scene of little Jackie Cooper crying—his signature in those days. Insisting that audiences wanted both a happy ending and waterworks from Cooper, Mayer demanded re-shoots resulting in the film as seen today.()

7. Disney’s 1950 Treasure Island and Robert Newton’s Long John Silver

While Robert Newton’s Long John Silver is definitive in the portrayal not just of the character but also of the pirate tropes that permeate popular culture, his performance in the 1950 Disney film directed by Byron Haskin owe certain debts to Fleming’s film. The Disney adaptation of the novel is culturally significant as the production company’s first full-color live-action film and because of Newton’s performance. Newton already had an impressive film résumé, not least for playing Bill Sikes in David Lean’s 1948 film Oliver Twist. In real life, he was also an alcoholic Englishman from the West Country, details that seem to find their way into his performance as both Sikes and Silver. Newton’s linguistic mannerisms and facial expressions define the character. As Kate Samuelson notes, his performance has defined how we imagine pirates to talk; there is a “‘Talk Like A Pirate’ day” (September 19), and she points out that when we do so, we are, in fact, talking like Newton’s Silver (). Being from the West Country and using Stevenson’s phrasing from the novel, Newton may be close to imitating the language patterns Stevenson evokes; however, Newton exaggerates both Silver’s expressions and his speech for comic effect, in a similar fashion to Beery before him. Silver becomes caricatured, while expressing a charm and humor that draws in the audience.11 For example, when the crew performs an onboard funeral service for the departed Arrow, Newton’s Silver acknowledges the end of the ceremony with the deliberately elongated “Argh-men” (). It is difficult not to laugh both at and with him here, at his villainous duplicity; the audience is forced into a conspiratorial relationship with Silver.

Another aspect that Haskin’s film shares with Fleming’s is the third-person camera angle. In this film, it is exploited further, as we follow Silver beneath decks to see him orchestrate the drunken disappearance of Arrow overboard and to see him eyeball and control his confederates (). Newton’s Silver does arrange the death of Arrow, but it is passive. In the text, the reader is left to guess at Silver’s involvement:

In the meantime, we could never make out where he got the drink. That was the ship’s mystery. Watch him as we pleased, we could do nothing to solve it; and when we asked him to his face, he would only laugh if he were drunk, and if he were sober deny solemnly that he ever tasted anything but water.

Haskin’s film shows us, without Jim’s presence, Silver encouraging Arrow’s drinking and, moreover, inserts a moment in which Silver stops George Merry from murdering Arrow with a dagger (). This alteration allows for Silver’s plotting but prompts viewers to think that, unlike the nightmarish pirate crew, Silver might not be as bloodthirsty.He was not only useless as an officer and a bad influence amongst the men, but it was plain that at this rate he must soon kill himself outright, so nobody was much surprised, nor very sorry, when one dark night, with a head sea, he disappeared entirely and was seen no more.()

This action occurs without the presence of Jim, who, as in the earlier film, becomes more of a narrative device, largely devoid of Stevenson’s character’s development from child to young adult. Bobby Driscoll’s character, similar to Cooper’s before him, is American (in order to appeal to Disney’s primary American youth audience). Driscoll’s Jim is reactive to the action, rather than proactive as he is in the novel. An example of this occurs as the Hispaniola reaches Treasure Island (): when Smollett confronts Silver as he and the other pirates are rowing for shore, Silver uses Jim as a human shield by holding a knife to his throat. In addition, when Jim is forced to defend himself against Hands (ibid., 1:10:16–11:19), he shoots the pirate with one pistol that had been given to him by Silver earlier in the film, rather than with the two pistols that he himself appropriates from the stockade before venturing out to the ship in Stevenson’s text. Such character tweaks force a change in the focus of the narrative: ultimately, in making Jim less proactive in his own destiny, the story becomes focused inevitably on Silver. Because of this shift, Newton’s Silver, and the storyline, had to appeal to audiences and not alienate them in a manner that Stevenson’s character might have done. This is achieved not only through comic padding of the character but also through tempering the violence that Silver commits throughout the film. The scriptwriters could not simply ignore Silver’s capacity for violence, but they made sure that the violence he does commit might be, to an extent, excused by the audience at the end of the film. The most obvious change is that we no longer witness Silver murder Tom; the scene is written out of the movie.

Disney’s sanitization of Stevenson’s character is confirmed by yet another different ending to the story. As with the 1934 film, we see Jim ultimately helping Silver escape (). Silver, having robbed his share of the treasure, takes Jim hostage and makes a deal with him: steer him out of the bay, and he will put Jim ashore. Jim agrees but then grounds the boat to thwart Silver’s escape. When Jim jumps ashore, Silver threatens to shoot him point blank; however, he drops the pistol, apparently unwilling to murder the boy. While Dr. Livesey and the squire attempt to catch up with them, Jim takes pity on the obviously panicked Silver and helps float the boat, allowing Silver’s escape. Dr. Livesey is given the final lines of the film: “I could almost find it in my heart to hope he makes it” (ibid., 1:34:57–35:02). This is a far cry from Stevenson’s Livesey, who is determined to see Silver suffer justice at the hands of the British navy—Blackbeard’s actual fate (). Moreover, Silver’s change—or failing—of heart in not shooting Jim ultimately warms the character to the audience: indeed, he is not a cold-blooded murderer and thief. Rather, he is a likeable scallywag who played the system, shot a few other pirates, and got away. Similar to Livesey, we feel he almost deserves to escape. It is worth noting Newton’s afterlife as Silver, which must in part be attributed to this performance and in part to Disney’s construction of his character. In 1954 he reprised the role in an Australian film entitled Long John Silver; he then played the character for the same company for a 1958 television series, The Adventures of Long John Silver. He also played the lead in the 1952 film Blackbeard, the Pirate. Newton’s performance as Silver is the prototype of the pirate trope in popular culture.

8. Conclusions

Put together, these narrative and character tweaks—the moderated capacity for violence, the humor of the performances of Beery and Newton, and the altered “happy” endings—offer a different pirate captain from Stevenson’s and ultimately create a new cinematic character that co-exists with the textual Silver. This is the American pirate figure. We use the word “American” because these movies, among so many other pirate films, were made by American studios with American money for American audiences. Louis B. Mayer may have inadvertently helped to define this character through his insistence on a happy ending and, by association, a softening of Silver’s cold-blooded escape. Even when the actor is British, as with Newton, he is performing for a market that was defined by American sensibilities, and his co-star, Driscoll, like Cooper before him, is very much the all-American boy. As part of the marketing drive for the 1950 film, Walt Disney visited Stevenson’s home in Edinburgh on Heriot Row, an event recorded for posterity at the Walt Disney Museum in San Francisco.12 The visit presumably was meant to imbue the film with a certain authenticity, tying it to its textual roots, so it is ironic that his film would so clearly alter the characters and story.

The enduring popularity of Disney’s film and Newton’s performance have inscribed Disney’s Long John Silver into popular consciousness, but this character is not the embodiment of Stevenson’s creation; rather he is a grandchild, to paraphrase Stevenson’s own description (). These changes in his character are made necessary because of the nature of the medium. If we were to look over Jim’s shoulder, or behind closed doors aboard the Hispaniola, at Stevenson’s Silver, we would see a monster, quite possibly not fit for a film marketed to children. Certainly, Silver would not be so warmly remembered by cinema audiences if we had witnessed what he was truly capable of or if he had, as Stevenson has it, simply abandoned Jim without a word, having robbed the party of some of the treasure: “The sea-cook had not gone empty handed. He had removed one of the sacks of coin … to help him on his further wanderings … Of Silver we have heard no more. That formidable seafaring man with one leg has at last gone clean out of my life” (). Filmmakers and their actors had to construct a character who would simultaneously exude artifice, cunning, a potential for violence that is rarely fully realized, and disarming charm. This is the American contribution to Stevenson’s character, which has helped to generate a multitude of afterlives for the notorious pirate captain. The cinematic pirate is not inferior to Stevenson’s originals but exists independently. Audience expectation, marketing, the mechanics of camera perspective, executive demands for happy endings, and American Jims, combined with issues of casting, have all contributed to subtle evolutions of character and aesthetics, creating these modern pirate tropes. Of course, creating an “American” pirate would not have been possible without the ambiguity of Stevenson’s original character, which allows for such creative interpretations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.J.H. and L.E.; formal analysis, R.J.H.; investigation, R.J.H. and L.E.; writing—original draft preparation, R.J.H. and L.E.; writing—review and editing, R.J.H. and L.E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Barrie, James M. 1921. Peter Pan and Wendy. New York: Scribner’s. First published 1904. [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter, Kevin. 1982. R. L. Stevenson on the Treasure Island Illustrations. Notes and Queries 29: 322–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dury, Richard. 2018. Film Versions of Treasure Island. The Robert Louis Stevenson Archive. Available online: http://www.robert-louis-stevenson.org/richard-dury-archive/films-rls-treasure-island.html (accessed on 17 October 2019).

- Fleming, Victor. 1934. Treasure Island. Featuring Wallace Beery and Jackie Cooper. Beverly Hills: MGM, Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dIM5hx_-I9w (accessed on 17 October 2019).

- Goodman, Bill. 2010. Treasure Island (1934). Turner Classic Movies. Available online: http://www.tcm.turner.com/tcmdb/title/2515/Treasure-Island/articles.html (accessed on 20 October 2019).

- Haskin, Byron. 1950. Treasure Island. Featuring Robert Newton and Bobby Driscoll. Burbank: Disney, Available online: https://www.amazon.com/Treasure-Island-Basil-Sidney/dp/B003QSFW9C/ref=sr_1_1?keywords=Treasure+Island+1950&qid=1571317350&sr=8-1 (accessed on 17 October 2019).

- Johnson, Charles. 2002. A General History of the Robberies and Murders of the Most Notorious Pirates. Edited by David Cordingly. Guildford: Lyons. First published 1724. [Google Scholar]

- Linehan, Katherine. 2003. Two Unpublished Letters from Robert Louis Stevenson to Thomas Russell Sullivan. Notes and Queries 50: 320–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, Jill P., and Robert E. May. 2011. Howard Pyle: Imagining an American School of Art. Champaign: University of Illinois Press. [Google Scholar]

- Michaelis, David. 2003. N. C. Wyeth: A Biography. New York: Harper Collins. First published 1998. [Google Scholar]

- National Park Service. 2019. African Americans at Jamestown. In Historic Jamestowne; August 9. Available online: https://www.nps.gov/jame/learn/historyculture/african-americans-at-jamestown.htm (accessed on 17 October 2019).

- Nollen, Scott Allen. 1994. Robert Louis Stevenson: Life, Literature and the Silver Screen. Jefferson: McFarland. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, Trey. 2009. Fatbeard. In South Park. Season 13, episode 7. New York: Comedy Central. [Google Scholar]

- Pyle, Howard. 1921. Howard Pyle’s Book of Pirates. New York: Harper. [Google Scholar]

- Roux, George, illus. 1885. Treasure Island. London: Cassell & Co. [Google Scholar]

- Samuelson, Kate. 2016. It’s Talk Like a Pirate Day—But Where Does Pirate Talk Really Come From? Time. September 19. Available online: https://time.com/4497168/international-talk-like-pirate-day/ (accessed on 20 October 2019).

- Stevenson, Robert Louis. 2012. Treasure Island. Edited by John Sutherland. Buffalo: Broadview. First published 1883. [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson, Robert Louis. 2012. My First Book. In Treasure Island. Edited by John Sutherland. Buffalo: Broadview, pp. 231–39. First published 1894. [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson, Robert Louis. 1986. Moral Emblems. Edinburgh: Polygon. First published 1921. [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson, Robert Louis. 1994. The Letters of Robert Louis Stevenson. Edited by Bradford A. Booth and Earnest Mehew. New Haven: Yale University Press, vols. 4–5. [Google Scholar]

- Wyeth, Newell C., illus. 1911. Treasure Island. New York: Scribner’s. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | Treasure Island was first serialized in the Young Folks from 1 October 1881 to 28 January 1882 before being revised for the first book edition, which was published in 1883. |

| 2 | Admittedly, the more minor figures are distinguishable in name only. Those pirates that play a more integral role in the plot are distinct, as in the case of Billy Bones, Blind Pew, Israel Hands, and, of course, Long John Silver. |

| 3 | An important model for Silver is Stevenson’s friend, the poet and sometimes literary agent W. E. Henley. They had met in Edinburgh, when Henley was recovering from tubercular disease, and Stevenson visited him in hospital. Writing to Henley in late May 1883, Stevenson states, “I will now make a confession. It was the sight of your maimed strength and masterfulness that begot John Silver in Treasure Island. Of course, he is not in any other quality or feature the least like you; but the idea of the maimed man, ruling and dreaded by the sound, was entirely taken from you” (). As part of his treatment, Henley had to have his left leg amputated below the knee (and not at the hip as with Long John Silver). |

| 4 | All subsequent textual citations from Treasure Island are taken from the 2012 Broadview edition, based on the 1883 first book edition. |

| 5 | Johnson also explains the possibility of a real buried treasure Teach is supposed to have had secured before his death (). |

| 6 | Carpenter published his article “R. L. Stevenson on the Treasure Island Illustrations” in 1982. The original piece may well have been meant for publication in the Magazine of Art, which, at the time, was edited by Henley and for which Stevenson wrote several pieces about art and literary illustration. |

| 7 | Another aspect of these illustrations that clearly influences cinema and Disney’s Long John Silver is color. Howard Pyle’s Book of Pirates reproduced several of Pyle’s canvases in full color. The most significant color that influences pirate films is red. Red has obvious associations of danger, mortality, and passion, and it becomes associated in Pyle’s work with the pirate captain. The influence of Pyle’s pirates is seen in the 1926 film The Black Pirate, the second film to experiment in the two-strip technicolor process, the results of which bring out strong reds in the final cut. May and May point out that Pyle’s Book of Pirates provided a “one-volume reference source for producers of films like The Black Pirate … and Captain Blood featuring Errol Flynn” (). The brutal pirate captain wears a red cloak in true Pyle fashion; the flesh tones are strong, and the blood is clearly contrasted. May and May claim that Disney, throughout the decades following the introduction of color live action, has either deliberately or coincidentally leaned on Pyle’s aesthetic model for pirates, including in the Pirates of the Caribbean series and, of course, in representations of Captain Hook of J. M. Barrie’s Peter Pan (ibid., p. 201). Barrie, with a nod to his inspiration, writes, “he was the only man that the Sea-Cook feared” (). We contend that this is also true of Newton’s Silver. A quick glance at Newton’s costume confirms Pyle’s aesthetic influence, not least in the long, flowing, red coat. Newton and his character are English, but his costume is American and is not Stevenson’s. We know this from the original text: when he dresses to come face-to-face with Captain Smollett, Stevenson describes Silver as “tricked out in his best; an immense blue coat, thick with brass buttons, hung as low as to his knees, and a fine laced hat was set on the back of his head” (our italics; ). Red has become the standard color of the pirate captain trope, which can be traced back through the earliest color films to Pyle’s illustrated stories. |

| 8 | Pyle was writing and illustrating his own pirate stories in America contemporaneously with Stevenson. On balance, it might be fair to say Pyle’s ultimate talent lay with the graver, whereas Stevenson’s lay with the pen. Stevenson wanted to master both, but despite some talent in the visual arts, understood that he did not possess the talent to illustrate his own work to a professional degree. Stevenson articulates his jealousy of those who, like Pyle, could both write and illustrate, in his poem “The Graver and the Pen,” published posthumously in Moral Emblems (). It is helpful to use pirates to explain this: Stevenson’s story has infiltrated popular culture, while Pyle’s illustrations of pirates have helped define visual culture. |

| 9 | Copyright protections make including copies of Wyeth’s illustrations, as well as stills from the 1934 MGM and 1950 Disney films, prohibitively expensive. All are available for viewing online. |

| 10 | The pirates in this film are American, as is Jim, although Jim’s allies are inexplicably British. Beery’s American accent possibly helped American audiences identify with the rebel pirate even more. |

| 11 | Nollen argues convincingly that this caricaturing is possibly to be expected from a visionary like Walt Disney, whose primary stock-in-trade up to this point had been cartoons (). |

| 12 | Though Robert Louis Stevenson did not write Treasure Island in this location—he began the novel in Braemar—Walt Disney’s visit speaks to Stevenson’s enduring, and expansive, sphere of influence. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).