Abstract

Engaging equally with ancient Greco-Roman and contemporary Euro-American paradigms of citizenship, this essay argues that experiences of civic integration are structured around figurations of island and archipelago. In elaboration of this claim, I offer a transhistorical account of how institutions and imaginaries of citizenship take shape around an “insular scheme” whose defining characteristic is displacement. Shuttling from Homer and Livy to Imbolo Mbue and Danez Smith, I rely on the work of postcolonial literary critics and political theorists to map those repetitive deferrals of civic status to which immigrants and refugees in particular are uniquely subject.

1. Introduction

“No man is an island,” the seventeenth-century poet and cleric John Donne memorably mused (Meditation 17). The modern banalization of Donne’s insight has tended to obscure the imaginative work entailed by equating islands with humans, even if only for the purposes of disavowal. Yet Donne’s presumption of island insularity would not pass muster among contemporary practitioners of what has come to be known as the new thalassology, for whom the very notion of the island as a self-contained and bounded entity—shorn of any connective ligatures—is dead on arrival; “only connect” is the principle to which many students of island networks nowadays subscribe.1 Taking root in the gap between these two models, this article locates an unusually felicitous transubstantiation of the paradoxical island in the institution of citizenship, especially as experienced by immigrants. From a transhistorical perspective, it is this institution that sublimates, and in the process mystifies, the myriad human transits from one insular civic body to another. The migrant’s suspension between welcome and rejection in the course of these transits is apparent not only during the initial exodus across expanses of water (or desert) but through the compulsive repetition that forces the differentiated citizen to remember their difference. To lift an image and a model from the Caribbeanist critic Antonio Benítez-Rojo, the island is ceaselessly repeated (Benítez-Rojo 1992). The dance of repetition commences at the very moment of arrival on the liminal shore, where the migrant—naked, Odysseus-like, before the searching gaze of a prospective host community—has to earn the polity’s trust. This dance’s choreography is describable both as a historical process and as an ideational phenomenon; the opening section of this article briefly considers the affordances recoverable from each.

2. The Island Condition

My title for this essay alludes to a series of legal opinions and court decisions that, in the aftermath of the Spanish-American War (1898), marked a decisive shift in the United States’ practice of what has come to be termed “differentiated citizenship.” This jurisprudence, which sought to clarify the civic statuses and prerogatives of the United States’ new island dependencies, spurred not only the reconceptualization of citizenship under the sign of empire, but a fresh articulation of the relationship between territoriality and insularity—at the same time that those indigenous communities still standing after the genocidal violence of the country’s westward expansion were being subjected to the internal insularization of the reservation system. To retrieve the significance of differentiated citizenship for this historical conjuncture and for its more contemporary permutations, I turn first to Rogers Smith, the historian who has perhaps done the most to catalogue the concept’s manifold dimensions:

Smith’s summons to attend to the complex interactions of differentiated citizenship and territoriality has become newly relevant in the wake of Hurricane María, which leveled Puerto Rico’s infrastructure on its way to killing nearly 3000 people. The public recognition that Puerto Rico’s residents are profoundly unequal before the law of American citizenship has received weekly confirmation with every news report on the ineptitude and paltriness of relief efforts on the island, and with every exhibition of callous disregard from senior federal officials who are intent on minimizing the scope of the devastation. These officials take their cue from an American president who shrugged off criticisms of the relief effort’s sluggishness with the comment that Puerto Rico is “an island surrounded by water—big water, ocean water.”3In those [insular] cases, as in others of the Progressive Era (including ones scrutinizing race and gender classifications), the US Supreme Court upheld legislative powers to create what scholars have come to call ‘differentiated citizenship.’ Several of the most important forms of differentiated citizenship then sustained have since been repudiated as systems of unjust inequality.But in the twenty-first century, many are contending that various contemporary forms of differentiated citizenship are necessary to achieve meaningfully equal membership statuses. These include distinct forms of territorial membership. And though all claims for particular types of differentiated citizenship are in some respects unique, they also make up a more general pattern that controversies over territorial membership can illuminate. That is because here—perhaps more starkly than in any other area of modern American citizenship laws—some of the most basic, enduring, and still unsettled questions of civic equality are again being explicitly contested.2

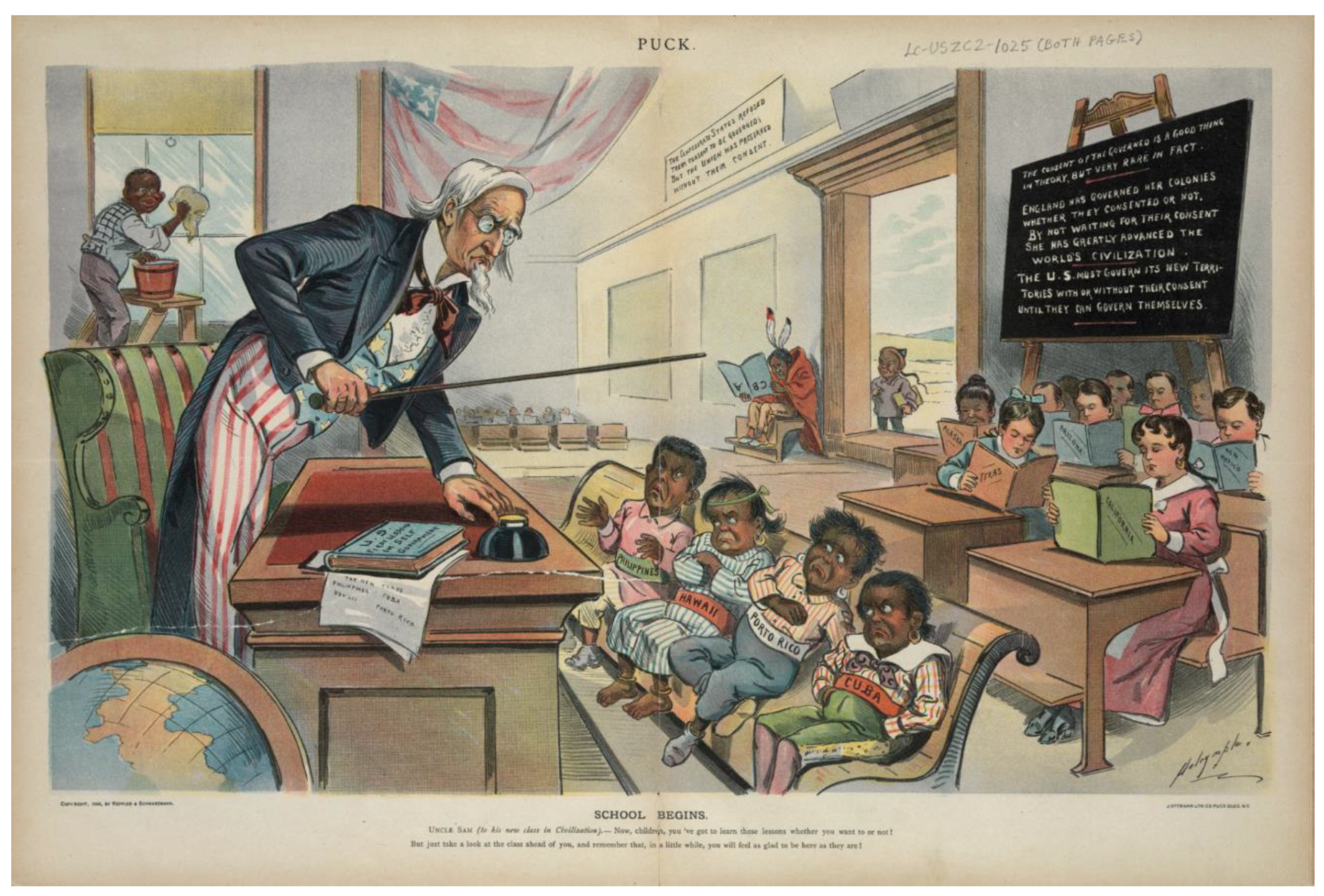

From its initial formulation in the era of the Insular Cases, the structural relationship between American mainland and island colony can be tracked across several discursive formats. The searing and alarming cartoon “School Begins,” published in Puck in 1899 and therefore contemporaneous with the Insular Cases (Figure 1), speaks with the force of a thousand words, titrating into visual form several lessons that are worth spelling out clearly. In illustration of Tat-Siong Benny Liew’s recasting of Miguel De La Torre, this classroom is “a room of class,”4 with its explicit interpellation of the newest American colonial acquisitions within the matrix of race and class being fused to the visual-spatial hierarchies of an idealized public-school classroom. The function of this hegemonic classroom as a site for the racial assignment and subjection of the externally and internally colonized is exposed in all its glory: the ambiguously aged and exaggeratedly racialized colonies occupy the naughty bench; the African-American janitor, Native American autodidact, and Asian immigrant on the threshold ring the margins. But most relevant for my purposes is the cartoon’s figural rendering of a style of imperial governance that unites all exploited and exploitable subjects under one discursive rubric. Those who are being sternly lectured by Uncle Sam are presumed incapable of governing themselves: in the tradition of great empires, the United States brandishes its right to educate the black and brown communities until these are deemed capable of exercising autonomy. Except that, of course, this autonomy is granted only within the force field of subjection; those island communities under the thumb of American hegemony will taste freedom only when they fully internalize the justice of their territorial domination. Only then, and provided they adopt the appropriately complaisant mien and deferential deportment, will they be permitted to migrate to the back of the room; yet the fantasy of shedding their racial assignment and assimilating to the gold standard of single-desk whiteness might still prove to be merely that, a fantasy. On this reading, the island colony is doomed never to be a piece of the continent, a part of the main.

Figure 1.

“School Begins” (Puck 1899). Image source: Library of Congress (https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2012647459/). Public domain.

Interacting with the cartoon’s colonizer semiotics is a related discourse with a shared genealogy: empire’s aptitude for the generation and cultivation of difference. Proceeding from the principle that imperial power is rooted in “the politics of difference,”5 one might scale up from the cartoon itself to a more sweeping synopsis of empire’s dialogues with constructs of differentiated citizenship, pinpointing instances in the historical record where the articulation and bestowal of differentiated citizenship become salient as a technology of penality and subjection. Here Greco-Roman antiquity has something to offer students of the Insular Cases and of twenty-first-century Puerto Rico, if the fons et origo of differentiated citizenship is traceable to an ancient Mediterranean imperial formation that experimented early and often with mechanisms for the practice of civic demarcation. It is important not to lose sight of that “if”: with groundbreaking research into the global variety of civic institutions in premodern and modern cultures taking off in recent years,6 there is no need—and certainly no ethical justification—for aprioristically privileging the Greco-Roman Mediterranean as a point of departure for the history of differentiated citizenship.

Studies of the history of citizenship have long accorded prominence to the Roman emperor Caracalla’s extension of Roman citizenship to all free residents of the Roman Empire in 212 CE (the so-called constitutio Antoniniana).7 Excluded from this grant were the unfree—i.e., slaves, of which there were millions in the Roman world—and a class of individuals who were afforded a measure of freedom but denied the full franchise (the dediticii).8 Despite these exclusions, Caracalla’s grant of citizenship has long been lionized as a transformative act that opened the door to a universal model of citizen status by untethering the legal protections that came with being a civis Romanus from ethnic origin, languages spoken, and religious observance. On a more meticulous and less triumphalist reading, however, other dimensions of the declaration come into view. The grant itself was the outcome of a multi-century process that had seen the imperial state continuously recalibrate citizenship as a device for social and imperial control. Rome’s deployment of civic status as an instrument for surgery on the polity had commenced in earnest over five centuries before Caracalla arrived on the scene, in the period of mid-republican Rome’s imperial expansion. On the march from central Italy, the bellicose city-state had imposed in 338 BCE a settlement on those communities that had rebelled from its alliance system. This settlement’s consequences would leave a lasting mark, and not only on the life course of the Roman Republic.

The settlement can be easily summarized.9 In the first rank were communities that, while kept under Rome’s thumb, were allowed to practice self-governance and were granted full Roman citizenship. In the second were communities that, even as they were forced to give up land to the Roman state for distribution to Rome’s citizens, were granted rights of intermarriage and commerce with Rome; however, these communities were not allowed to strike relationships with other communities except through the direct mediation of Rome. Still other communities were granted partial citizenship, the notorious civitas sine suffragio: this “benefit” came with full liability for military service but no right to vote or hold office at Rome. In this fashion, differentiated citizenship was born—and it was not long before tensions materialized in its wake. By the last decade of the fourth century, the communities being threatened with forcible incorporation into the Roman imperial state equivocated as to whether to accept or defy an invitation to join Rome’s alliance under unequal terms. In 306 BCE, the Hernici, a tribal configuration in central Italy, declined Roman citizenship. Shortly afterwards, another community joined them in resistance, voicing in response to Roman demands its collective conviction that citizenship would amount to punishment. According to the Roman historian Livy:

This episode brings into focus a concern that has not lost its edge in the millennia since Livy wrote: under what conditions does the state’s assignment of second-class citizenship do double work as a species of punishment? For the Aequi, the punishment inheres in the denial of choice, the obstruction of their copia legendi.11 The sentiment would not be unfamiliar to Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait communities in Australia, or other Indigenous and First Nation communities elsewhere throughout the settler-colonialist world whose agitation for genuine opportunities to practice self-governance and self-determination is regularly met with velvet-gloved denials of choice.12… temptationem aiebant [sc. Aequi] esse ut terrore incusso belli Romanos se fieri paterentur; quod quanto opere optandum foret, Hernicos docuisse, cum quibus licuerit suas leges Romanae civitati praeoptaverint; quibus legendi quid mallent copia non fuerit, pro poena necessariam civitatem fore.…The Aequi responded that the demand was patently an attempt to force them under threat of war to suffer themselves to become Roman: the Hernici had shown how greatly this was to be desired, when, granted the choice, they had preferred their own laws to Roman citizenship. To those to whom the opportunity of choosing what they wanted was not granted, citizenship would of necessity be a type of punishment.10

The ramifications of this repetitive denial for civic subjects (especially but not only second-class subjects) inform this essay’s interest in one metaphorical representation of denial as a design principle of citizenship. Even though the Aequi were on Rome’s radar some decades before the Roman first state applied itself to projecting power over the sea, the metaphor I have in mind is a maritime one. This essay will execute its trans-temporal and trans-spatial toggle between the ancient Mediterranean and modern Puerto Rico, and between the classical Aegean and the Black Aegean,13 by leveraging one proposition: that imaginaries of citizenship work to nest individual and communal identities within figurations of island and archipelago. As a complement to new histories of citizenship that discern in ancient Greece and Rome the contours of a heterodox civics,14 I will propose an ideational insular scheme that has less to do with the actual presence of islands or with their (ancient and modern) status as sealed-off spaces for the sequestration of luxury and wealth than with a fantasy of connectivity across distance that takes shape around the sign of the island—understood here as a mode of opening up and closing off, of welcoming some and denying others at real and hyperreal ports of entry. Athar Mufreh’s Catalyst piece for this volume drew attention to the “spatial governmentality” of the private citizenship now being enacted within the suburban communities of Palestine even as Palestinian statehood itself is continuously thwarted.15 What I have in mind is a scheme for mapping the territories of spatial governmentality that are traversed by the migrant, with the metonym of the island as my guide.

The historical and contemporary magnetism of islands as sites for the determination of admissibility to the polity would seem to warrant an engagement with citizenship that rigorously probes its “discursive production of insularity”—its nesology—all the more so now, as the purposing of islands into carceral pens for the forcibly displaced makes regular headlines.16 From Manus Island to Winston Ntshona’s The Island,17 the insular landscaping of citizenship calls out for assessment. Driven to the islands of notional or presumptive or partial citizenship, the aspirant to civic incorporation is soon confronted (tantalized, even) by the possibility that the true and final island might be somewhere else. Off they go in pursuit, on a never-to-be-completed journey of displacements and deferrals. The Cyclopean terror in store for the traveler who embarks on the journey of citizenship is not the destruction of nostos but the prospect of never-ending repetition, the closed loop of inconclusive tests for fidelity. Framed in these terms, citizenship takes its rightful place as one of the most potent and resilient means for the mystification of human displacement ever devised. Under the penumbra of this mystification, movement is re-inscribed simultaneously as the liberating exercise of freedom and (more ominously) as an unruliness to be policed and corralled.18

For cracking the code of mystification, few figures are as good to think with as “the perpetual immigrant,” the protagonist of Demetra Kasimis’ trenchant examination of the place of the metic in classical Athenian democracy.19 There is much one might say—and much that still needs saying—about citizenship’s shape-shifting in response to the unique demands and opportunities of maritime encounter, and not only with respect to classical Athens. If the history of chattel slavery is bound up with the sea, and if the history of citizenship is bound up with chattel slavery, it would stand to reason that the history of citizenship is bound up with the sea as well.20 But this essay will not attempt either a historically comprehensive demonstration of this fact pattern or a sociological exposition of its structural underpinnings; several generations of Caribbeanists have been hard at work on both fronts.21 The intuition guiding my essay meanders more poetically, conditioned by the same sensibility that inspired the poet Kamau Brathwaite to open the “Islands” section of his 1973 trilogy with James Baldwin’s haunting image of a messenger arriving to tell a long-suffering soul that “a great error had been made, and that it was all to be done again.”22 My meander will take me across disciplinary lines in recovering the civic nesology that organizes migrant subjectivity, with particular attention to labor and anxiety as the twin poles around which the compulsive repetition of citizenship as island-hopping ordeal is organized.

With the term “nesology,” I follow Antonis Balasopoulos in destabilizing the boundary between geographical ways of thinking and textual modes of ordering the world—and in foregrounding the island as a unit of spatial knowledge that is “epistemologically volatile”.23 By “labor,” I designate the hard and grinding slog of striving towards civic incorporation, for oneself or for one’s community, in the teeth of those mechanisms of Othering that motor at their highest gear to obstruct and delay; it is the uncompensated labor of home-building in hostile surroundings, all while girding oneself for the prospect that another journey and another expedition in home-building await. Finally, by “anxiety,” I mean not only the state famously defined by Freud as “expecting the danger or preparing for it” but the psychic anguish of never feeling quite completely at home because of the steady and ineluctable whir of those gears—and because of those reminders, always there to greet the traveler from one island to the next, of their irreconcilable and insurmountable difference from those host communities that cloak themselves in the fictions of permanence and stability.

Attentive to the quilting of these strands within the fabric of citizenship, this essay will move from a brief overview of frustrations with the terminology and baggage of Euro-American citizenship (Section 3) to a recuperative reading of the “repeating island” paradigm as voiced separately by a Homeric refugee and by a Roman historian (4) and finally to a closing exercise in psycho-biography and autoethnography that shuttles between the lessons of contemporary fiction and poetry on one end and the lessons of personal experience on the other (5).

3. Definitions of Citizenship: Binary and Bimodal

What are the advantages of characterizing citizenship as an insular scheme? By way of indirect answer, we could do worse than entertain some of the modern objections that have been raised to citizenship as an institutional form. Dissatisfaction with the concept and practice of citizenship is swelling, especially (though by no means solely) in the twenty-first-century United States. From blog posts advocating the retirement of the word “citizen” to the popularization of alternatives such as “denizen,”24 the terminology of civic belonging has come under increasing scrutiny of late. In recent years, frustration with the term “citizen” has intensified. This frustration has received a boost in American and global contexts from those who—taking a page from political theorist Judith Shklar—contend that, much as historically “[t]he value of citizenship was derived primarily from its denial to slaves, to some white men, and to all women” in the years before “the four great expansions of the suffrage”, so too contemporary citizenship remains fixated on restriction and denial.25

Even if the rejection of citizenship in favor of lexical and conceptual alternatives were to continue gaining traction, it is not clear that Americans long accustomed to trumpeting their democratic experiment as a Whiggish narrative of progressive expansions of the franchise will ever come to grips with the fact that the continuing refusal of the franchise to those designated as non-citizens—or as second-class citizens before whom barriers and impediments to the right to vote are swiftly erected and doggedly maintained—is the imaginative and structural foundation for their enjoyment of certain civic privileges. Along the twentieth- and twenty-first-century axis of the color line, the ordering of citizenship remains predicated on insularizing racial exclusions. Writing on the eve of the United States’ entrance into World War II, the novelist Richard Wright hitched insular metaphor to racial subjection: “The word ‘Negro’, the term by which, orally or in print, we black folk in the United States are usually designated is not really a name at all nor a description, but a psychological island…”26 Maritime imagery has been repeatedly tapped by Black Atlantic writers, for many of whom the legacies of the transatlantic slave trade’s forced displacement across the water retain their force not only in the contemporary civic protocols of the Global North but in the linear pseudo-progressivism of what Michelle Wright has termed Middle Passage epistemology.27

A vast scholarly literature has sprouted around the histories and dilemmas of citizenship. If only to plot some coordinates for the nesologies of Section 4 and Section 5, let me first set out a template for historicizing citizenship that stands at the very opposite end of this essay’s hermeneutic sequencing: the political theorist Michael Walzer’s succinct and influential periodization of the institution’s evolutionary arc.28 For Walzer, there are “two different understandings of what it means to be a citizen,” one developed and modeled in Greco-Roman antiquity (Walzer privileges the “Greco” side of the hyphenated clustering) and another formulated and honed in the early-modern period. The first and quintessentially Greco-Roman model “describes citizenship as an office, a responsibility, a burden proudly assumed; the second describes citizenship as a status, an entitlement, a right or set of rights passively enjoyed. […] The first assumes a closely knit body of citizens, its members committed to one another; the second assumes a diverse and loosely connected body, its members (mostly) committed elsewhere.”29 Walzer insists that the latter and not the former structures twentieth- and twenty-first-century experiences of the civic, although the galvanizing force and romantic allure of the former do resurface from time to time.

In charting the transition from antiquity’s versions to the modern Euro-American dispensation, Walzer decides against a linear narrative that begins with ancient Greece and Rome, opting instead to open his treatment in medias res with the early-modern and specifically French revolutionary moment whose call for dramatic and violent social transformation was premised in part on the resuscitation of antiquity’s civic paradigms. The zigzags of citizenship’s imperialization—already discernible in classical Athens but taken to new heights as the Mediterranean was violently absorbed into Rome’s imperium—would complicate any linear emplotment, hence, the turn to the reception of Greco-Roman paradigms in European early modernity. For Walzer, the meaning of the French revolutionary moment, and of the predecessor and contemporaneous neoclassicizing projects spanning a whole range of disciplines that fueled its fire, was that it brought to the fore the nasty side of recreating an ancient civic ethics (in this specific case a republican ethics) within the early-modern nation-state. Whereas the ancient Greco-Roman city-state had been populated with citizen bodies for whom public life was organically all-consuming, those “moderns” desirous of a return to that fully immersive model of high-spirited civic engagement had to give careful thought to how best to impress that commitment upon the minds and hearts of the nation-state’s citizens. The Jacobin solution was violence, not only of the externally focused martial variety but of the family-defying and disavowing variety. It is not exactly a shocker that eighteenth-century French neoclassical art fixates on exemplary instances of civic virtue lifted from the Roman tradition, such as Horatius killing his sister (Figure 2). For such enthusiastic public devotion to become the paramount affective attachment of each and every single citizen, what would be required was nothing more and nothing less than a species of psychological violence capable of permanently sundering the citizen’s attachment to any domain previously parceled off as private or domestic. Thus, in Walzer’s distillation of the lessons of revolutionary Jacobinism, “There is no road that leads back to Greek or Roman citizenship except the road of coercion and terror…”30

Figure 2.

Louis Jean François Lagrenée, Horatius Killing His Sister (1753). Image source: Wikimedia Commons (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Lagrenée_Horace_venant_de_frapper_sa_soeur.jpg). Public domain.

Walzer briskly somersaults from the eighteenth-century paroxysms of North Atlantic modernity to the crisis of the twentieth-century nation-state with scarcely any consideration of intermediate inflection-points or contrapuntal genealogies. To name only one conspicuous oversight, one would be hard pressed to identify in his essay any anticipation of Dipesh Chakrabarty’s summons to provincialize Europe (Chakrabarty 2000). In executing his somersault, Walzer does propose a secondary distinction between ancient Greco-Roman and modern Euro-American flavors of citizenship, this one having to do with the rhythms of intense civic participation. With rare exceptions, he notes, efflorescences of a single-minded 24/7 investment in public activism on the part of citizens of modern liberal nation-states tend to be of relatively short duration and to occur within narrow temporal windows. As capitalism and the liberal-democratic system steered individuals towards cultivating niches of privacy that were partially or fully secluded from the view of others, it became progressively more challenging to sustain intense involvement in public life. The enticements of privacy—and the impediments to public-facing individual agency, mainly though not exclusively in the form of the financial capital needed to enter the political arena and the social and psychological capital needed to maintain one’s equipoise while in it—were enough to choke off this intense involvement in the long term. Nowhere, according to Walzer, is this wax and wane more apparent than in the history of those movements that fought to expand access to citizenship: “The labor movement, the civil rights movement, the feminist movement have all generated in their time a sense of solidarity and an everyday militancy among large numbers of men and women. But these are not, probably cannot be, stable achievements; they don’t outlast the movement’s success, even its partial success.”31

One obvious inference is that it is tiring to pursue around-the-clock civic exertion, although Walzer is not clear on the institutional and structural factors that make the performance of political action in neoliberal democracies so exhausting.32 In any case, if we augment his list—tacking on the abolitionist movement at the front and the LGBTQIA, environmental, disabilities, and immigrant and refugee rights movements at the back end—the roll-call of projects to diversify the franchise might incline us towards a different conclusion: in the life course of a liberal-democratic state such as the United States, there is always a non-insignificant group of citizens beyond those holding office or those casting the vote who are engaged in the practice of a citizenship that is more akin to the all-consuming ancient variety than its more detached early-modern iterations. Not easily reconciled to Walzer’s scheme is the prominence of non-citizens in the most labor-intensive work of civic agitation and renewal, from the undocumented of Euro-America to the Dalits of the Indian subcontinent; I will circle back to this observation shortly.

For now, one takeaway is that the texture of citizenship is never—and arguably has never been—uniform across the polity. To improve on Walzer, we could revert to the nesological cartography introduced earlier and envision citizenship within any polity as a network of islands: of communities seeking greater political visibility and of allies fighting on their behalf, of individuals and communities improvising a politics-on-the-move in the course of their displacement from one island to the next.33 On its own merits, Walzer’s account is too monochromatic to yield a fine-grained civic mapping, although to his credit he anticipates this line of criticism by cautioning that “Dualistic constructions are never adequate to the realities of social life.”34 The plotting of an ancient conception of citizenship as succeeded or replaced (or even just occluded) by an early-modern innovation is a variation of that well-worn dialectic strategy according to which the modern credentializes itself as modern: as coming after and in the process displacing the ancient. The tidiness of such an arrangement regularly conceals the other types of displacement—epistemic, political, historical—that are experienced by those constantly on the move in search of the security and protection that come with full civic status. It is these types of displacement, and their instantiation under the auspices of differentiated citizenship, that I visit next.

4. The Repeating Island and the Repetitive Refugee

As a first step in devising a lexicon for citizenship that faithfully captures its dependence on experiential and cognitive displacements, one could do worse than center the emotion of anxiety. I am interested in the production of anxiety as a sign and symptom of those psycho-dialogic processes whereby communities construct and triangulate civic relations with the migrant Other seeking admission to their ranks. This anxiety comes in two primary colors: on one hand, the anxieties generated within civic communities by the perceived or actual attributes of the migrant or refugee or asylum-seeker (I will not, in what follows, observe hard distinctions between these categories, without denying the reality on the ground that such disctinctions have); on the other, the anxieties experienced by the migrant as she negotiates the bureaucratic and procedural obstacles through which the anxiety of the receiving or host community is translated into targeted oppression.35 These anxieties are wired into the reproduction of citizenship as a form of différance that patches together difference and deferral. Of course, these anxieties do not assume quite the same forms in the civic regimes of Greco-Roman antiquity as they do in twenty-first-century modernity. In the midst of an epochal transition on the part of the nation-states of the global North away from imperial settler-colonialist projects of scientific cartography and towards those xenophobic populisms that fetishize complete control of borders and the bodies that cross them, we would do well to remember that premodern states were for the most part far less fixated (and far less technologically equipped to fixate) on outsiders who entered their territories; the more terrifying prospect for ancient polities was the likelihood that the outsider would enter the citizenship rolls. But even this distinction, and the assignment of historically and contextually specific civic anxieties to each side of the ancient and modern divide, is less straightforward than it might seem at first blush.36

As my own autobiographical experience of these anxieties and of the labor required to manage them is so viscerally embodied, I have increasingly gravitated towards interpretive models that privilege the body as a location for the production of civic knowledge. The theoretical scaffold of “copropolitics” has proven exceptionally sturdy in this respect,37 not least because my self-fashioning and that of multiple generations of migrant Americans has been mediated by Emma Lazarus’ iconic poem “The new Colossus,” inscribed on the Statue of Liberty’s pedestal. This poem is not only about the ethical urgency of receiving the foreigner, but about the importance of receiving the foreigner who has been hailed as waste product, forced from their country of origin to the maritime margins. Here are the relevant lines:

- “Keep, ancient lands, your storied pomp!” cries she

- With silent lips. “Give me your tired, your poor,

- Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

- The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

- […]” (vv. 9–12; emphasis mine)

The complexity of this phenomenon has not been fully accounted for in recent treatments of migration and asylum. Not even Linda Rabben’s thoroughly researched 2016 history of the idea and institution of sanctuary, with its nimble progression from primatological research into the reception of strangers among apes to the status of sanctuaries in medieval and early-modern conflicts between church and state,41 locks its sights on one specific discursive task of sanctuary as concept and practice: to incubate those propositions about the likely attributes of human beings in desperate flight that slowly and ineluctably replace complex multi-dimensional lives with spectral conjurations of the asylum-seeker as victim and/or criminal.42 The singular and uniquely pernicious perversity of this process is that asylum-seekers are compelled into ventriloquizing these ghosts. Like the children seated in Uncle Sam’s classroom, they must internalize their own subjection in order to be made legible as (potential) civic subjects. This internalization demands regular and uncompensated physical and emotional labor, from the daily work of presenting oneself as unthreatening before the collective gaze to the lifelong slog of self-indoctrination in the belief that she has chosen her host correctly.43 If only to clarify the operations of this psychic process through the magic of defamiliarization, let me propose one ancient Greek and one Roman text as emblematic of the metaphorical island-hopping that is required to navigate both the arduousness of sanctuary-seeking and the never-ending postponement of civic incorporation for the displaced—with the important and necessary caveat that neither the pre-polis backdrop of the Greek text nor the imperial substrate of the Roman one corresponds neatly to the civic architecture of the twenty-first-century nation-state.

On the Greek side, my port of call will be Homer: not the Odyssey, although its portrayal of island-hopping created a powerful and durable spatial model for the migrant striving of interest to this essay;44 but rather the Iliad, whose dramatization of sanctuary-seeking shines an even brighter light on civic nesologies. By Book 9, the devastating consequences of Achilles’ continued withdrawal from the fighting following his quarrel with Agamemnon have become plain. The Greeks are being slaughtered right and left, as the Trojans and their allies come ever closer to incinerating the Greeks’ ships and wiping out their beach encampment. Yielding to necessity and to the belated recognition of his own catastrophic shortsightedness, Agamemnon finally sends an embassy of Greeks to Achilles, with the hope of persuading him to give up his anger and re-enter the fight as the fates and lives of his fellow Greeks hang in the balance. Unmoved by the embassy’s entreaties and indifferent to the gifts with which Agamemnon seeks to entice him back into the Greek fold, Achilles declares his intention to return home. It is at this tense juncture that another voice pipes up: Achilles’ mentor Phoenix, to whom Achilles offers the option of staying with the Greeks after the hero departs home for Phthia with his Myrmidons. Phoenix’s speech smuggles into the epic a capsule autobiography of a sanctuary-seeker who is now being forced to recapitulate his social difference in a moment of acute personal and collective crisis:45

| Therefore apart from you, dear child, I would not be willing To be left behind, not were the god in person to promise he would scale away my old age and make me a young man blossoming as I was that time when I first left Hellas, the land of fair women, running from the hatred of Ormenos’ son Amyntor, my father; who hated me for the sake of a fair-haired mistress. For he made love to her himself, and dishonoured his own wife, my mother; who was forever taking my knees and entreating me to lie with this mistress instead so that she would hate the old man. I was persuaded and did it; and my father when he heard of it straightaway called down his curses, and invoked against me the dreaded furies that I might never have any son born of my seed to dandle on my knees; and the divinities, Zeus of the underworld and Persephone the honoured goddess, accomplished his curses. Then I took it into my mind to cut him down with the sharp bronze, but some one of the immortals checked my anger, reminding me of rumour among the people and men’s maledictions repeated, that I might not be called a parricide among the Achaians. […] Then I fled far away through the wide spaces of Hellas and came as far as generous Phthia, mother of sheepflocks, and to lord Peleus, who accepted me with a good will and gave me his love, even as a father loves his own son who is a single child brought up among many possessions. He made me a rich man, and granted me many people, and I lived, lord over the Dolopes, in remotest Phthia, and, godlike Achilleus, I made you all that you are now, and loved you out of my heart… | ὡς ἂν ἔπειτ᾽ ἀπὸ σεῖο φίλον τέκος οὐκ ἐθέλοιμι λείπεσθ᾽, οὐδ᾽ εἴ κέν μοι ὑποσταίη θεὸς αὐτὸς γῆρας ἀποξύσας θήσειν νέον ἡβώοντα, οἷον ὅτε πρῶτον λίπον Ἑλλάδα καλλιγύναικα φεύγων νείκεα πατρὸς Ἀμύντορος Ὀρμενίδαο, ὅς μοι παλλακίδος περιχώσατο καλλικόμοιο, τὴν αὐτὸς φιλέεσκεν, ἀτιμάζεσκε δ᾽ ἄκοιτιν μητέρ᾽ ἐμήν: ἣ δ᾽ αἰὲν ἐμὲ λισσέσκετο γούνων παλλακίδι προμιγῆναι, ἵν᾽ ἐχθήρειε γέροντα. τῇ πιθόμην καὶ ἔρεξα: πατὴρ δ᾽ ἐμὸς αὐτίκ᾽ ὀϊσθεὶς πολλὰ κατηρᾶτο, στυγερὰς δ᾽ ἐπεκέκλετ᾽ Ἐρινῦς, μή ποτε γούνασιν οἷσιν ἐφέσσεσθαι φίλον υἱὸν ἐξ ἐμέθεν γεγαῶτα: θεοὶ δ᾽ ἐτέλειον ἐπαρὰς Ζεύς τε καταχθόνιος καὶ ἐπαινὴ Περσεφόνεια. ἔνθ᾽ ἐμοὶ οὐκέτι πάμπαν ἐρητύετ᾽ ἐν φρεσὶ θυμὸς πατρὸς χωομένοιο κατὰ μέγαρα στρωφᾶσθαι. τὸν μὲν ἐγὼ βούλευσα κατακτάμεν ὀξέϊ χαλκῶι: ἀλλά τις ἀθανάτων παῦσεν χόλον, ὅς ῥ᾽ ἐνὶ θυμῶι δήμου θῆκε φάτιν καὶ ὀνείδεα πόλλ᾽ ἀνθρώπων, ὡς μὴ πατροφόνος μετ᾽ Ἀχαιοῖσιν καλεοίμην […] φεῦγον ἔπειτ᾽ ἀπάνευθε δι᾽ Ἑλλάδος εὐρυχόροιο, Φθίην δ᾽ ἐξικόμην ἐριβώλακα μητέρα μήλων ἐς Πηλῆα ἄναχθ᾽: ὃ δέ με πρόφρων ὑπέδεκτο, καί μ᾽ ἐφίλησ᾽ ὡς εἴ τε πατὴρ ὃν παῖδα φιλήσῃ μοῦνον τηλύγετον πολλοῖσιν ἐπὶ κτεάτεσσι, καί μ᾽ ἀφνειὸν ἔθηκε, πολὺν δέ μοι ὤπασε λαόν: ναῖον δ᾽ ἐσχατιὴν Φθίης Δολόπεσσιν ἀνάσσων. καί σε τοσοῦτον ἔθηκα θεοῖς ἐπιείκελ᾽ Ἀχιλλεῦ, ἐκ θυμοῦ φιλέων… |

Phoenix’s flight across Hellas will have taken him over land and sea, exposing him both to the maritime fragmentation of the Greek landscape and the more figurative island-hopping of searching for a new home. As he reminds his sullen ward Achilles, he had fled his home and traveled far “through the wide spaces of Hellas” after provoking the rage of his natal family. Responding to an act of supplication, he had attempted to stand up for his mother and in the course of that defense compounded his father’s wrong with a wrong of his own. Lacerated to the point of (verbalized) castration by his father’s curses, he had been goaded into almost killing his old man out of anger. What had held him back? A divine force, reminding him of what would happen if he had been forced to live life as a parricide; the shadow of Oedipus creeps into the mythological background here. Nonetheless, his mind turbulent with emotions, Phoenix could not stay home any longer and took off, on the journey that finally brought him to the domains of Achilles’ father Peleus; only there was he, a deracinated and family-less man, not only received with good will but loved as a father loves his son. So beloved was Phoenix in Phthia that, even after being deprived by his father’s curses of the opportunity to raise his own children, he came to be entrusted with the rearing of Peleus’ son. That trust empowered him to become a full member of the community at Phthia, and to invest himself in the nurturing of the prodigy that Achilles eventually became.

Phoenix’s story-telling builds up to a seemingly unobjectionable lesson: Achilles, set aside your anger and reconcile yourself to Agamemnon, before it is too late. But the exhortation to transcend one’s anger for the sake of the community’s well-being is imparted by a sanctuary-seeker turned mentor, a sanctuary-seeker with a shady past. Phoenix claims not to have killed his father, but we only have his word that he did not go ahead with the deed. In fact, one of the most distinguished ancient interpreters of Homer was so horrified by the possibility that Achilles might have received advice from a near-parricide that he proposed deleting the lines in which Phoenix admits to his murderous designs against his father.46 In any case, despite his past of wrath, Phoenix had nonetheless been given a second chance, making full use of it to be the father to Achilles that his father was not to him. Yet to discharge his obligations as a father figure and to instruct Achilles in the limits and complications of wrath, Phoenix has to plumb the depths of the migratory past that had haunted him even after his successful incorporation into the community of Phthia and the household of Peleus. “The point of this autobiography,” Jasper Griffin has claimed, “is to show Phoenix as having no other love but that for Achilles.”47 The more stirring and relevant point for this essay is that this love, and with it all the talents that were flexed towards nurturing the young Achilles, is the gift of an immigrant who flees home under dubious circumstances, consigning himself to a life of marginality in the process—only then to luck out with the one host and the one host community whose willingness to receive him in good will had unlocked Phoenix’s own special capacity to be the father and mentor that he had never had. The felicitous pairing of host and exile was not a foreordained outcome: the reference to flight across “the wide spaces of Hellas” (δι᾽ Ἑλλάδος εὐρυχόροιο) decorously veils multiple episodes of rejection, at the hands of those communities that refused their hospitality to the cast-off Phoenix. It was only after his reception at Phthia, whose fertile soil—nourished by the manure of its flocks—synecdochically cues its social generosity,48 that his previously inert capacity for attachment was reactivated. Such was the success of this reactivation that Phoenix would find himself one day leaving his new home in order to accompany his specially gifted charge on another journey over wide spaces, this time across the waters of the Aegean to Troy. What we learn not from the Iliad but from the greater Trojan mythic cycle is that Phoenix never sailed back to his adoptive home.

The social re-integration of ‘criminals’ turned refugees is a Homeric commonplace: among the most conspicuous examples involves another person in Achilles’ tent during that fateful Book 9 exchange: Patroklos.49 I focus on Phoenix because his self-disclosure is uncomfortably reminiscent of contemporary anxieties about welcoming the Other who happens to trail a criminal history, as voiced by those anti-immigrant zealots who have succeeded not only in branding many immigrants with the stigmata of criminality but in forcing all immigrants, as a condition of their acceptance into their new polities, into the question-and-answer protocol of forswearing any link to crime whatsoever. One response to this discursive framing has been to insist on the benefits that ensue from receiving immigrants with open arms; in this spirit, we might take Phoenix’s speech as an invitation to reflect on the good that comes out of providing sanctuary to the foreigner and entrusting him or her with the secondary responsibilities that flow from full acceptance in the community. But matters are not so easily settled. There is, for starters, Phoenix’s admission to having done something wrong and his further confession that he was prepared to do something still more wicked. While Phoenix’s autobiography is not styled as a confessional report, the (calculated?) transparency of this self-disclosure as a criminal is wired into an archaic and classical Greek expectation that the sanctuary seeker was guilty of some crime and therefore a likely candidate for recidivism, whether advertent or inadvertent;50 it also anticipates sanctuary’s coupling to the confession of crime in the European medieval period.

Nor does Phoenix’s opening up about his own past actually tip the scales of persuasion, since Achilles remains stubborn in his resolve. The rift between Achilles and Agamemnon is not healed until Patroklos’s death goads Achilles into a fury without analogue or precedent in the autobiography of his favorite mentor. If Achilles does learn anything from Phoenix’s speech, it is that the figure of the immigrant is forever shrouded in disgrace; this knowledge comes to the surface in Achilles’ complaint that Agamemnon had treated him as if he were some “dishonoured metanastes,” a word properly translated not with Richmond Lattimore’s “vagabond” but with Bryan Hainsworth’s “refugee.”51 The advice delivered by the sanctuary-seeker who had matured into the ideal mentor has apparently no other effect besides stamping him as a former (and always?) criminal and activating within Achilles’s mind the association of the refugee with criminality. Shrouded in that past, Phoenix is confined to the insularizing enclosure within which that past is never forgotten. Moreover, the association of the refugee with crime creates near-perfect conditions for denying and deferring the Other’s full incorporation into a new community—or, at a minimum, for forcing the reperformance of that association as a requisite for being granted legitimate standing within that community.

The stereotyping of the immigrant as a vector for crime hardly stops with the Iliad. Its persistence across the millennia is apparent not only in the xenophobic language nowadays embraced by the populist nationalisms of late-stage capitalism,52 but in the application protocols of immigration systems around the world that interrogate immigrants extensively about their criminal histories and presume that they will be dishonest about their pasts unless compelled into truth. In response to the impositions of this contemporary dispensation, it has proven tempting for some classicists to press into service texts and practices from the Greco-Roman Mediterranean that offer some glimpse—however ephemeral—of the possibility of a more radically inclusive civic paradigm; sometimes these efforts produce little more than platitudinous paternalism.53 The classical text that is most often adduced as exhibiting a commitment to this species of inclusion turns out on closer inspection to be riddled with ambivalences. I am speaking of the Roman historian Livy’s account of the origin-story for the asylum, the institution whose historical and cultural legacies would already in antiquity become a wrestling-ground for Greeks and Romans.54 The Janus-like duplicity of the Romulean asylum comes through forcefully in A. de Sélincourt’s amusingly free and revealingly tendentious translation:55

Much has been made of this passage’s glorification of the migrant presence as foundational to Rome’s future attainments, and of the historian’s insinuation that, in a deep sense, all claims of civic autochthony and communal rootedness in the soil are simply a sleight of hand—a rhetorical transmutation of a motley assortment into bona fide citizens. All this and so much more can be slotted with little difficulty into Andersonian schemes of imagined community.56 My objectives in citing this passage, however, are rather different.Deinde ne vana urbis magnitudo esset, adiciendae multitudinis causa vetere consilio condentium urbes, qui obscuram atque humilem conciendo ad se multitudinem natam e terra sibi prolem ementiebantur, locum qui nunc saeptus descendentibus inter duos lucos est asylum aperit. Eo ex finitimis populis turba omnis sine discrimine, liber an servus esset, avida novarum rerum perfugit, idque primum ad coeptam magnitudinem roboris fuit.In antiquity, the founder of a new settlement, in order to increase its population, would as a matter of course shark up a lot of homeless and destitute folk and pretend that they were ‘born of earth’ to be his progeny; Romulus now followed a similar course: to help fill his big new town, he threw open, in the ground—now enclosed—between the two copses as you go up the Capitoline hill, a place of asylum for fugitives. Hither fled for refuge all the rag-tag-and-bobtail from the neighbouring peoples: some free, some slaves, and all of them wanting nothing but a fresh start. That mob was the first real addition to the City’s strength, the first step to her future greatness.

If make-believe is essential to the construction of that kinship whereby the refuse “from the neighbouring peoples” metamorphose into citizens, it is noteworthy that the fiction proceeds from the assumption that those on the move must be (at best) mediocrities. The assumption is contradicted by the historical record, not least in the Roman annalistic tradition’s preservation of stories about the migration of elites; those fortunate enough to hop from polity to polity tend to have some resources, at least relative to those who are left behind.57 But the ideological work veiled by this assumption hums along regardless: “they don’t send us their best.” Common both to the self-report of Phoenix and to the Livian representation of the asylum is the encoding of mobility and those on the move as inherently suspicious; the only redemption available to immigrants lies in the stabilizing action of the host community that with its offer of welcome also assigns them a role. The darker side of that welcome, however, is the prospect that those marked with the scarlet letter of desperate flight will from that first moment of entrance in the community be interpellated as riff-raff.

The myth of the asylum could and almost certainly did function as a device for justifying the direction of the state’s normative gaze towards those individuals and communities who in Livy’s own lifetime were being menaced with discipline and punishment: first Julius Caesar and then Augustus had some firm ideas about how to order, regulate, and quantify the civic body.58 Seen in this light, the Livian asylum was a fiction for negotiating those anxieties about aspiring members of the civic body that could not simply be willed away or dismissed out of hand, given that these anxieties had to be sustained if the state was to carry out its work of assigning every person a place. The labor involved in sustaining these anxieties would in ancient Rome come to rely increasingly on an imperial management strategy that repetitively strung out past and future candidate communities for citizenship into islands of unequal status. On one level, the legend of the asylum enacted the illusionistic trick of yoking the rough crowd to the triumphal procession of Roman greatness. On another level, the legend re-authorized the application of Roman power to demarcate, circumscribe, and grid different communities through the imputation of criminality and backwardness. The success of this feat of mystification was conditional on selling members of these communities on the fantasy that those who had migrated from difficult or unsavory circumstances would one day become bona fide citizens just like everyone else—even if, in the end, they could never be.

5. The Fever Dream of Civic Belonging

To the extent that the noble simplicity and calm grandeur of the state is presumed to reside in fixity and permanence, the human body in motion is seen either as a disruption of its glacial stability or as an outcome of the state’s determination to will this stability into being. As the Livian asylum story exemplifies, that stability is rooted not in the soil of autochthonous timelessness but on certain controlling fictions. By reading against the grain, we can recover from Livy’s text an alternative script for narrating the anxieties of those immigrants in the grip of twenty-first-century displacements. Their hope is to find a place of succor, a place between the tree groves; but what is to be done when the materialization of that hope hinges on an act of ventriloquism, namely the substitution of one’s own inner sense of self with the psychic projection of the state? In modern settings, this projection works through the carrot-and-stick (or bait-and-switch) of populating the immigrant’s mind with a set of mythic narratives that exalt their host state and with a set of anxieties about the Scylla and Charybdis of that state’s bureaucracy and carcerality.

Sometimes occluded in contemporary debates about immigration and civic belonging is the question of whether as a general principle, the institutions of civil society have an affirmative moral obligation to protect the most vulnerable from the blunt-force administration of anxiety, and if so under what circumstances. Among the strategies through which the carceral-immigration systems of the modern Global North perfect their grasp on the minds and bodies of immigrants is the propagation of terror, which takes the form not only of the active and unavoidable paranoia about being rounded up for detainment and deportation but of the crushingly relentless rituals that are staged to make the immigrant “feel like a problem.”59 Perhaps this anxiety is simply one branch of the generalized insecurity through which the (post)modern state manages the polity, as Jacques Rancière has detailed.60 Be that as it may, the highly specific and quite regularly racialized anxiety of being made to feel like a problem inflicts devastating harm on the minds and bodies of immigrants.61 Among the many forms that this anxiety takes is the sensation of never standing on terra firma, of always feeling condemned to life as “a small and rotting boat/A frightened boat—without a paddle and unmanned…”62

The state’s game of indefinitely deferring the arrival of marginalized communities on the shores of full citizenship through the weaponization of anxiety depends partly on co-opting as gatekeepers those individuals who have journeyed successfully to the final destination. The most arresting depiction of this process that I have come across is not in a Greco-Roman text (though much remains to be said about imperial Rome’s recruitment of new and aspiring citizens into its militarized exploitation of borderlands) but in a recently published novel: Imbolo Mbue’s Behold the Dreamers, which follows a Cameroonian immigrant couple on their harrowing pursuit of legal status in the United States. Early in the narrative, the protagonist Jende receives some words of consolation and exhortation from his bumbling lawyer Bubakar after the family’s first asylum application is rejected:

This gruff wisdom is unmasked over the course of the novel as a spectacular deception, trotted out by Bubakar—himself an immigrant—in an attempt to keep the spigots of his customers’ payments turned on. At every turn, Jende and his spouse Neni are tantalized by the specter of that ever-elusive adjustment to legal status; meanwhile, the experiences of the novel’s secondary characters undermine the notion that citizenship will open the door to a shimmering future of anxiety-free stability. The best-case scenario in store for them is the “citizenship in question” that has lately elicited comment from political theorists.64 But Jende and Neni are denied even this. With no happy ending to the couple’s migratory travails and no redemptive culmination to years of waiting and praying and bureaucratic maneuvering, they are eventually forced back across the Atlantic to Cameroon.We’ll keep on trying our own way, and you keep on sleeping with one eye open, eh? Because until the day you become American citizen, Immigration will always be right on your ass, every single day, following you everywhere, and you’ll need money to fight them if they decide they hate the way your fart smells. But Inshallah, one day you’ll become a citizen, and when that happens, no one can ever touch you. You and your family will finally be able to relax. You’ll at last be able to sleep well, and you’ll begin to really enjoy your life in this country.63

I am a formerly undocumented immigrant from the Greater Antilles for whom the saga of Jende and Neni speak equally to those nesological properties of citizenship that guide my professional work and to the dreams of citizenship that have shaped my identity. Citizenship is constantly on my mind because I have lived for twenty-seven of my thirty-four years in a country that denies me the name of citizen, and because the conditions that act to suppress biographical narratives like mine from public visibility are structurally akin to those that work towards the effacement of the internally colonized, from Puerto Rico to the projects.65 The most effective counter I have been able to muster to my adoptive country’s denial is to seek out and construct models of citizenship that eschew repetitive denial in favor of radical inclusion, often with the help of texts that receive and reformat Greco-Roman antiquity. In its most upliftingly irenic incarnation, this radical inclusion would be co-extensive with that limitless expanse of welcome that has been freshly summoned into verse by the poet Danez Smith:

- do you know what it’s like to live

- on land who loves you back?

- no need for geography

- now, we safe everywhere.

- point to whatever you please

- & call it church, home, or sweet love.

- paradise is a world where everything

- is sanctuary & nothing is a gun. (“summer, somewhere”)66

- … once, a white girl

- was kidnapped & that’s the Trojan War.

- Troy got shot

- & that was Tuesday. are we not worthy

- of a city of ash? of 1000 ships

- launched because we are missed? (“not an elegy”)67

Pivotal to the reproduction of these axiological conceits is the demand that immigrants constantly perform their worth. With enough time and island-hopping, the demand is successful at inscribing itself into the immigrant’s subconscious. During my adolescent years, when I first came to terms with what it might mean to grow up as an undocumented immigrant in the United States, I was often visited by a recurring nightmare in which I would awaken from my slumber to find myself back in the New York City homeless shelters where my family had spent a year of my childhood. Although I would come to awareness in the dream as my eight-year-old (soon to be nine-year-old) self, inhabiting the body that accompanied my family on its entrance to the shelter system in the summer of 1993, I was cursed with foreknowledge: I knew that we would be confined in the shelter system for a year, and subjected regularly to the verbal questioning and physical prodding of social workers, medical personnel, and teachers; that my mother would continue exploring how to legalize our family’s stay in the United States, experiencing frustration at every turn; that we would be placed out of the shelter system and into new neighborhoods; that I would be admitted to an independent private school where I would study Latin and ancient Greek, seeking in the prestige economy of these languages a deliverance into civic integration; that I would carry the secret of our immigration status with me on my weekday commutes to school and on the journey to college; and that I would be absolutely powerless to effect any change to this itinerary that might result in a materially better outcome for my family. This was the nightmare that chased after me for years and years, adding fresh layers to the sedimentation of delay as my family crawled to legal immigrant status.

Even the acquisition of differentiated citizenship, first in the form of permanent residence and then (in my mother’s case) naturalization, did nothing to dispel the regularity of the nightmare’s visitations. Carlos Aguilar has recently sounded the call for an “undocumented critical theory” that attends more faithfully and flexibly to the psychosocial contours of the undocumented experience.68 For the purposes of this contribution, I close with an appeal to my own undocumented psycho-biography in order to foreground the extent to which the insular case of imperfectly realized citizenship is a head case: the Sisyphean labor of having always to retrace one’s journey across uneven terrain and fragmented domains, made all the harsher and unremitting by the bludgeoning of those accosting voices who insist that all the immigrant must do is perform the proper rituals and wait in line.69 Now, it may be objected that to speak of insular cases or nesologies as a psychic phenomenon (as I have done) or to specify an ontology for the process that begins prior to “the birth of territory”70 (as I have also done) is a misbegotten enterprise. Or some readers may grumble, as one anonymous referee did some years ago in response to an essay that was conceived in a very similar vein to this one, that “the author’s personal information is inappropriate in a work of historical scholarship.” But the leveraging of the personal is, in the first instance, a tactic for resisting the signature imposition of insular citizenship on the bodies of the marginalized: the shattering realization that one is a “disposable subject,”71 liable to be cast away on a moment’s notice into the deep blue sea. To resist this imposition is also to resist the reproduction of those imaginary cartographies by which black and brown bodies are commanded (through acts of racist prestidigitation) to “return” home, to that outre-mer envisaged as their only appropriate abode. In defiance of these acts and of the mental maps that underpin them, this essay has endeavored to provide a transhistorical rendering of citizenship’s torments that, in contradistinction to citizenship itself, does not confine itself to borders or shores—of linearity, historicity, and most of all disciplinarity.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

Some of the material in this essay first saw the light of day at a 2017 Princeton conference on belonging and exclusion in the age of transnationalism; my thanks to Desmond Jagmohan and Patricia Fernández-Kelly for the invitation to participate. My heartfelt gratitude goes to Elena Isayev and Evan Jewell for inviting me to contribute to this volume, waiting very patiently on my submission, and improving it with their comments; to the referees for their sharp-eyed criticisms; to audiences at the Bread Loaf School of English at Middlebury College, Gustavus Adolphus College, the University of Minneapolis, Taipei American School, Rhodes College, Yale University, Brandeis University, UC Berkeley, UC Santa Barbara, and UCLA for feedback on different portions of this essay and the project from which it is taken; and to my students at the Freedom and Citizenship summer program at Columbia University for inspiration.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Aguilar, Carlos. 2018. Undocumented Critical Theory. Cultural Studies, Critical Methodologies. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, Michelle. 2018. None of Us Deserve Citizenship. The New York Times. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/12/21/opinion/sunday/immigration-border-policy-citizenship.html (accessed on 20 January 2019).

- Anderson, Benedict. 2006. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origins and Spread of Nationalism. London: Verso. First published 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Ando, Clifford. 2011. Law, Language, and Empire in the Roman Tradition. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ando, Clifford, ed. 2016a. Citizenship and Empire in Europe 200–1900: The Antonine Constitution after 1800 Years. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Ando, Clifford. 2016b. Making Romans: Citizens, subjects, and subjectivity in Republican Empire. In Cosmopolitanism and Empire: Universal Rulers, Local Elites, and Cultural Integration in the Ancient Near East and Mediterranean. Edited by Myles Lavan, Richard E. Payne and John Weisweiler. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 169–86. [Google Scholar]

- Bagelman, Jennifer. 2016. Sanctuary City: A Suspended State. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Balasopoulos, Antonis. 2008. Nesologies: Island form and postcolonial geopoetics. Postcolonial Studies 11: 9–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, James. 1998. Tell Me How Long the Train’s Been Gone: A Novel. New York: Vintage International. First published 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Bayoumi, Moustafa. 2008. How Does It Feel to Be a Problem? Being Young and Arab in America. New York: Penguin Books. [Google Scholar]

- Beard, Mary. 2015. Ancient Rome and Today’s Migrant Crisis. The Wall Street Journal. Available online: https://www.wsj.com/articles/ancient-rome-and-todays-migrant-crisis-1445005978 (accessed on 21 January 2019).

- Benítez-Rojo, Antonio. 1992. The Repeating Island: The Caribbean and the Postmodern Perspective, 2nd ed. Translated by J. Maraniss. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bergholz, Max. 2018. Thinking the nation. American Historical Review 123: 518–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boochani, Behrouz. 2018. No Friend but the Mountains. Translated by O. Tofighian. Sydney: Pan Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Brathwaite, E. Kamau. 1973. The Arrivants: A New World Trilogy. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Burbank, Jane, and Frederick Cooper. 2010. Empires in World History: Power and the Politics of Difference. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Campa, Naomi. 2018. Positive freedom and the citizen in Athens. Polis 35: 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carne-Ross, Donald S. 2010. Classics and Translation: Essays by D.S. Carne-Ross. Edited by Kenneth Haynes. Lewisburg: Bucknell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ceccarelli, Paola. 2012. Water and identity in the ancient Mediterranean. Mediterranean Historical Review 27: 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakrabarty, Dipesh. 2000. Provincializing Europe: Postcolonial Thought and Historical Difference. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cornejo Villavicencio, Karla. 2017. The Psychic Toll of Trump’s DACA Decision. The New York Times. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2017/09/08/opinion/sunday/mental-health-daca.html (accessed on 2 October 2018).

- de Sélincourt, Aubrey, trans. 1971. Livy. The Early History of Rome. Harmondsworth: Penguin. [Google Scholar]

- Dench, Emma. 2005. Romulus’ Asylum: Roman Identities from the Age of Alexander to the Age of Hadrian. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ducloux, Anne. 1994. Ad Ecclesiam Confugere: Naissance du Droit D’asile Dans les Eglises (IVe–Milieu du Ve s.). Paris: De Boccard. [Google Scholar]

- Eberle, Lisa P. 2017. Making Roman subjects: Citizenship and empire before and after Augustus. TAPA 147: 321–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elden, S. 2013. The Birth of Territory. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Finley, Moses I. 1981. Economy and Society in Ancient Greece. Edited by Brent D. Shaw and Richard P. Saller. New York: Viking. [Google Scholar]

- Fynn-Paul, Jeffrey. 2009. Empire, monotheism and slavery in the greater Mediterranean region from antiquity to the early modern era. Past and Present 205: 3–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, Armando. 2019. Disposable subjects: Staging illegality and racial terror in the borderlands. Critical Philosophy of Race 7: 160–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gettel, Eliza. 2018. Recognizing the Delians displaced after 167/6 BCE. In Displacement and the Humanities: Manifestos from the Ancient to the Present. Edited by Elena Isayev and Evan Jewell. Special issue. Humanities 7: 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilroy, Paul. 2019. Never again: Refusing Race and Salvaging the Human. The Holberg Lecture. Available online: https://www.holbergprisen.no/en/news/holberg-prize/2019-holberg-lecture-laureate-paul-gilroy (accessed on 14 July 2019).

- Goff, Barbara, and Michael Simpson. 2007. Crossroads in the Black Aegean: Oedipus, Antigone, and Dramas of the African Diaspora. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gopal Jayal, Niraja. 2013. Citizenship and Its Discontents: An Indian History. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, Benjamin. 2018a. Citizenship as barrier and opportunity for ancient Greek and modern refugees. In Displacement and the Humanities: Manifestos from the Ancient to the Present. Edited by Elena Isayev and Evan Jewell. Special issue. Humanities 7: 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, Benjamin. 2018b. Approaching the Hellenistic polis through modern political theory: The public sphere, pluralism and prosperity. In Ancient Greek History and Contemporary Social Science. Edited by Mirko Canevaro, Andrew Erskine, Benjamin Gray and Josiah Ober. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, pp. 68–97. [Google Scholar]

- Griffin, Jasper, ed. 1995. Homer: Iliad IX. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hainsworth, Bryan, ed. 1993. The Iliad: A Commentary. Vol. III: Books 9–12. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hammer, Dean. 2002. The Iliad as Politics: The Performance of Political Thought. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, Virginia. 2018. Nauru Refugees: The Island Where Children Have Given up on Life. BBC News. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-45327058 (accessed on 21 January 2019).

- Hernández, Arelis R., Mark Berman, and John Wagner. 2017. San Juan Mayor Slams Trump Administration Comments on Puerto Rico Hurricane Response. The Washington Post. Available online: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/post-nation/wp/2017/09/29/san-juan-mayor-slams-trump-administration-comments-on-puerto-rico-hurricane-response (accessed on 31 July 2019).

- Honig, Bonnie. 2001. Democracy and the Foreigner. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Horden, Peregrine, and Nicholas Purcell. 2000. The Corrupting Sea: A Study of Mediterranean History. Malden: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Isayev, Elena. 2017. Between hospitality and asylum: A historical perspective on displaced agency. International Review of the Red Cross 99: 75–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jameela, Maryam. 2018. Movements through trauma: How to see ourselves. In The Fire Now: Anti-Racist Scholarship in Times of Explicit Racial Violence. Edited by Azeezat Johnson, Remi Joseph-Salisbury and Beth Kamunge. London: Zed Books, pp. 199–208. [Google Scholar]

- Jewell, Evan. 2019. (Re)moving the Masses: Colonisation as Domestic Displacement in the Roman Republic. In Displacement and the Humanities: Manifestos from the Ancient to the Present. Edited by Elena Isayev and Evan Jewell. Special issue. Humanities 8: 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasimis, Demetra. 2018. The Perpetual Immigrant and the Limits of Athenian Democracy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kotef, Hagar. 2015. Movement and the Ordering of Freedom: On Liberal Governances of Mobility. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhrt, Amélie. 2014. Even a dog in Babylon is free. In The legacy of Arnaldo Momigliano. Edited by Tim Cornell and Oswyn Murray. London and Turin: The Warburg Institute and Nino Aragno Editore, pp. 77–87. [Google Scholar]

- Lattimore, Richmond, trans. 1957. Homer. The Iliad. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lavan, Myles. 2016. The spread of Roman citizenship, 14–212 CE: Quantification in the face of high uncertainty. Past and Present 230: 3–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrance, Benjamin N., and Jacqueline Stevens, eds. 2017. Citizenship in Question: Evidentiary Birthright and Statelessness. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Liew, Tat-Siong Benny. 2017. Black scholarship matters. Journal of Biblical Literature 136: 237–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luiselli, Valeria. 2017. Tell Me How It Ends: An Essay in Forty Questions. Minneapolis: Coffee House Press. [Google Scholar]

- Márquez, Roberto. 2010. A World among These Islands: Essays on Literature, Race, and National Identity in Antillean America. Amherst and Boston: University of Massachusetts Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mbue, Imbolo. 2016. Behold the Dreamers: A Novel. New York: Random House. [Google Scholar]

- McConnell, Justine. 2013. Black Odysseys: The Homeric Odyssey in the African Diaspora since 1939. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, Pankaj. 2017. Age of Anger: A History of the Present. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. [Google Scholar]

- Mossman, Hannah. 2009. Narrative island-hopping: Contextualising Lucian’s treatment of space in Verae Historiae. In A Lucian for Our Times. Edited by Adam Bartley. Newcastle-upon-Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, pp. 47–62. [Google Scholar]

- Mufreh, Athar. 2017. Private citizenship: Real estate practice in Palestine. In Displacement and the Humanities: Manifestos from the Ancient to the Present. Edited by Elena Isayev and Evan Jewell. Special issue. Humanities 6: 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, Jan-Werner. 2016. What Is Populism? Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- Padilla Peralta, Dan-el. 2015a. Undocumented: A Dominican Boy’s Odyssey from a Homeless Shelter to the Ivy League. New York: Penguin Press. [Google Scholar]

- Padilla Peralta, Dan-el. 2015b. Barbarians inside the Gate, Part I: Fears of Immigration in Ancient Rome and Today. Eidolon. Available online: https://eidolon.pub/barbarians-inside-the-gate-part-i-c175057b340f (accessed on 2 October 2018).

- Padilla Peralta, Dan-el. 2015c. The Immigration Iliad. Matter. Available online: https://medium.com/matter/the-immigration-iliad-6727955ae085 (accessed on 2 October 2018).

- Padilla Peralta, Dan-el. 2017a. Waste. In Liquid Antiquity. Edited by Brooke Holmes and Karen Marta. Geneva: Deste, pp. 116–19. [Google Scholar]

- Padilla Peralta, Dan-el. 2017b. Classics beyond the Pale. Eidolon. Available online: https://eidolon.pub/classics-beyond-the-pale-534bdbb3601b#.1s1gzxn0g (accessed on 2 October 2018).

- Padilla Peralta, Dan-el. 2018. Documentary Anxieties. The Fabulist. Available online: https://www.aesop.com/us//r/the-fabulist/documentary-anxieties (accessed on 22 January 2019).

- Padilla Peralta, Dan-el. Forthcoming. Peace and shit: Aristophanes as a primer on copropolitics. In progress.

- Petty, Kate Reed. 2017. Is It Time to Retire the Word ‘Citizen’? Los Angeles Review of Books. Available online: https://blog.lareviewofbooks.org/essays/time-retire-word-citizen/ (accessed on 2 October 2018).

- Purcell, Nicholas. 2016. Unnecessary dependences: Illustrating circulation in pre-modern large-scale history. In The Prospect of Global History. Edited by James Belich, John Darwin, Margret Frenz and Chris Wickham. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 65–79. [Google Scholar]

- Rabben, Linda. 2016. Sanctuary and Asylum: A Social and Political History. Seattle: University of Washington Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rancière, Jacques. 2010. Dissensus: On Politics and Aesthetics. Edited and Translated by Corcoran Steven. London: Continuum. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw, Brent D. 2017. Africa. In Handwörterbuch der Antiken Sklaverei. Edited by Heinz Heinen. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag, vol. 1, pp. 49–57. [Google Scholar]

- Sherwin-White, Adrian N. 1972. The Roman citizenship: A survey of its development into a world franchise. ANRW I: 23–58. [Google Scholar]

- Shklar, Judith N. 1991. American Citizenship: The Quest for Inclusion. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Rogers M. 2015. The Insular Cases, differentiated citizenship, and territorial statuses in the twenty-first century. In Reconsidering the Insular Cases: The Past and Future of the American Empire. Edited by Gerald L. Neuman and Tomiko Brown-Nagin. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, pp. 103–28. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Danez. 2017. Don’t Call Us Dead: Poems. Minneapolis: Graywolf Press. [Google Scholar]

- Solnit, Rebecca. 2017. Tyranny of the Majority. Harper’s Magazine. Available online: https://harpers.org/archive/2017/03/tyranny-of-the-minority/ (accessed on 2 October 2018).

- Song Bo, Saum. 1885. A Chinese View of the Statue of Liberty. The Sun. Available online: https://www.newspapers.com/clip/16261363/letter_from_saum_song_bo_re_statue_of/ (accessed on 20 January 2019).

- Sorensen, Martin S. 2018. Denmark Plans to Isolate Unwanted Migrants on a Small Island. The New York Times. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/12/03/world/europe/denmark-migrants-island.html (accessed on 21 January 2018).

- Stewart, Owen. 2017. Citizenship as a reward or punishment? Factoring language into the Latin settlement. Antichthon 51: 186–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terrenato, Nicola. 2019. The Early Roman Expansion into Italy: Elite Negotiation and Family Agendas. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]