Abstract

16 June 2018. London Stadium. Beyoncé and Jay–Z revealed the premiere of the music video Apeshit. Filmed inside the Louvre Museum in Paris, Beyoncé’s sexual desirability powerfully dialogues with Western canons of high art that have dehumanized or erased the black female body. Dominant tropes have historically associated the black female body with the realm of nature saddled with an animalistic hypersexuality. With this timely release, Apeshit engages with the growing current debate about the ethic of representation of the black subject in European museums. Here, I argue that Beyoncé transcends the tension between nature and culture into a syncretic language to subvert a dominant imperialistic gaze. Drawing on black feminist theories and art history, a formal analysis traces the genealogy and stylistic expression of this vocabulary to understand its political implications. Findings pinpoint how Beyoncé laces past and present, the regal nakedness of her African heritage and Western conventions of the nude to convey the complexity, sensuality, and humanity of black women—thus drawing a critical reimagining of museal practices and enriching the collective imaginary at large.

1. Introduction

It was 16 June 2018, at the London Stadium. American singer Beyoncé Giselle Knowles (alias Beyoncé) and rapper Shawn Corey Carter (alias Jay–Z) presented the premiere of the music video Apeshit (The Carters 2018) during their On the Run II tour. The Carters—one of the most famous couples in the Rhythm and Blues and Hip–Hop music industry—took everybody by surprise by releasing the flagship song on social media for their joint album Everything is Love. Following Jaz–Z’s infidelity and the Carters’ subsequent marital tension, the duo appears united, loving, and stronger than ever. Ricky Saiz directed the video which had been filmed inside the Louvre Museum in utmost secrecy fifteen days prior. The result was six minutes of visual feast and technical feat. With ten million views online in less than twenty-four hours, the news rapidly made international headlines. Queen Bey had found a new throne in the Parisian epitome of French enlightenment—and this did not happen by coincidence.

Critics, fans, and detractors were quick to speculate in the media on the meanings embedded in Apeshit’s lyrics and visual narratives. According to film director and journalist Rokhaya Diallo (Randanne 2018), the video clip celebrates a contemporary black popular culture being placed on an equal footing with the greatest European works of art in an iconic museum. Triumphant Jay–Z and Queen Bey could look Leonardo da Vinci’s most famous painting Mona Lisa (circa 1503) directly in the eyes. As Diallo expresses, if La Joconde left a lasting mark on the history of the Renaissance, today it is the turn of the Carters to be a reference in our time. Author Nail Ver–Ndoye (Randanne 2018) presents a similar analysis and reinforces Diallo’s point. Ver–Ndoye notes that what made Apeshit such a landmark event is the manner in which the video clip engages with a younger and disadvantaged demographic which is so often left out of such elitist establishments. The figures have proven them right. In 2018, the Louvre’s attendance rose twenty-five per cent. The success of the Louvre’s specially edited visitor trails, Jay–Z and Beyoncé at the Louvre, clearly contributed to this sharp increase (The Louvre 2019). Visitors could follow in the footsteps of their idols while learning about the history of the artworks featured in the video. Apeshit is not just a commercial success limited to the music industry. It is also a social phenomenon that deserves scholarly attention.

An aspect that captures the attention is the centrality and sensuality of the black female body unveiled in Apeshit’s iconography. Shadows of semi-naked dancers eclipse the canonical body of Western masterpieces. Beyoncé’s assertive display of black sexual desirability dialogues with European conventions of high art which have historically erased or dehumanized the black female forms. Examples of these discriminatory practices have ranged from the long-lasting depictions in European art history of the Ethiopian princess Andromeda—famous in Greek mythology for her distinctive beauty—as if she were a white woman (Figure 1) (McGrath 1992), to the Dutch painter Christiaen van Couwenbergh’s confronting oil painting Rape of the Negro Girl (1632) (Figure 2). Today, the subject is up for debate with the exhibition Le Modèle Noir de Géricault à Matisse (The Black Model from Géricault to Matisse) on view at the French Musée d’ Orsay (Paris) from the 26 March to the 21 July 2019. The display is based on Denise Murrell’s Ph.D. Dissertation (Murrell 2018) at Columbia University (New York) that raises the question of the (sexual) agency of the black female muse in French modern masterpieces. One of the aims of the exhibition is to present “a new perspective on a topic which has been disregarded for too long: the major contribution of black people and personalities to art history” (Musée d’Orsay 2019).

Figure 1.

Domenico Guidi, Andromeda and the Sea Monster (1694). Marble. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Source: https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/204720.

Figure 2.

Christiaen van Couwenbergh, Rape of the Negro Girl (1632). Oil on canvas. Musée des Beaux-Arts de Strasbourg. Source: Wikipedia (Photograph Rama) https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Rape_of_the_negro_girl_mg_0026.jpg.

So, what could the presence of choreographed black female bodies within an institution with such an imperialist history indicate in the video clip? Ben Zimmer’s (2018) essay on the etymology of the title of the song may give us a clue. Today, the slang expression Apeshit expresses the idea of going crazy through frenzied excitement or anger. Initially, the term “to go ape” had been fashionable in the American youth culture of the 1950s, “conjuring the image of an ape’s out-of-control behavior” (Zimmer 2018). Shortly after, Air Force pilots and other sections of the military made the term their own with more violent implications during the Korean War. To “go ape” became to “go apeshit”. Zimmer details how in the song, Jay–Z and Beyoncé also resort to other animalistic imageries as a way of reclaiming these derogatory terms often used as racial slurs. As he concludes, “the song’s evocation of ‘the crowd goin’ apeshit’—especially when juxtaposed with the staid, classical European art in the video—is transgressive in more ways than one” (Zimmer 2018). In other words, Zimmer points to the subversive articulation of the notions of “nature” and “culture” intrinsic to Apeshit’s lyrics and visual palette. His commentary alludes to the way the colonialist and imperialistic discourses have historically conceptualized the black subject as a primitive and animalistic “other” in order to justify strategies of spoliation and domination. By opposition, the Western subject has defined its identity in the elevated attributes of the cultural realm in a reassuringly binary vision of the world. The comparisons of French Minister of Justice Christiane Taubira to a monkey by the magazine Minute in 2013 (Willsher 2013), and of First Lady Michelle Obama to an “ape in heels” by West Virginia county worker Pamela Ramsey Taylor in 2016 (Jamieson 2016) are relevant examples. It signifies once again how ingrained these dehumanizing conceptualizations of the black female body are in the collective imagination, and how challenging it is for the status quo when black subjects affirm their places in valorized social spheres.

In this essay, I argue that with Apeshit, Beyoncé transcends the tension between the realms of nature and culture into a syncretic sexual language to subvert a dominant imperialist gaze. I use the term “subvert” to express how Beyoncé’s creative strategies undermine the foundations of a hegemonic visual culture rooted in a long history of alienation of the black female body and identity. The following analysis will trace the genealogy and stylistic expression of this visual language. In her review of the conceptualization of black women in the French literary world, Tracy Denean Sharpley–Whiting pays tribute to the writings of Francophone Caribbean authors who have offered “a critical oppositional space where black women have been able to redefine, indeed reinvent, themselves” (Sharpley-Whiting 1999, p. 119). In the same fashion, I am interested in the way Beyoncé reimagines a space of possibilities for this exploration of the (collective) self, a space emancipated from ruling esthetics. What there is to gain in the exercise is a greater comprehension of how Beyoncé is crafting new erotic, esthetic, and most importantly political territories in the legacy of pioneer black female visual artists who have previously challenged dominant representations of the black female body in the public consciousness. This understanding is essential not just to pave the way to future resistance, but also to appraise how the emancipatory power of such creative practices have expanded the sexual, racial, and social collective imaginary at large.

2. Methodology

Building on art history and black feminist theories, I will perform a formal and contextual analysis of a selection of video stills in order to unpack their layers of complexity. The choice of a methodology in the discipline of art history is dictated not just by the resonance between Apeshit’s visual narratives and the Louvre’s collection of artworks, but also through Beyoncé being a fully interdisciplinary artist. In Homecoming: a Film by Beyoncé (2019), a self-reflective documentary about Queen Bey’s musical show at the Coachella Valley Music and Arts Festival (2018), Beyoncé mentions how she leaves nothing to chance in her creative process by being “super specific about every detail” (Knowles-Carter 2019) (1:23:28–1:24:07). For her Coachella performance, she “personally selected each dancer, every light, the material on the steps, the height of the pyramid, the shape of the pyramid. Every patch was hand sewn. Every tiny detail had an intention” (Knowles-Carter 2019) (1:24:14–1:24:27). Apeshit is arguably a work of art which comprises a succession of tableaux vivants. Each of these has a great visual and conceptual depth that mandates multiple readings and closed inspections. Tableaux vivants—also called living pictures—were popular art forms and pastimes in Europe from the late 18th century to the 19th century. Adults and children enjoyed dressing-up, arranging properties, and creating scenarios. Silent and still, they assumed carefully choreographed poses in the likenesses of prominent paintings and historical scenes (Reed 2017, p. 10). The genre has ranged from sacred nativity plays to risqué entertainments. In all cases, tableaux vivants have always displayed high levels of artistry and stylization.

While tableaux vivants are currently out of fashion, Arden Reed (2017) traces the influence of their artistic conventions in today’s resurgence of more contemplative forms of visual experiences in contemporary art. In the hectic pace of the modern technologized age constantly under the “pressure of acceleration” (Reed 2017, p. 11), living pictures “require a sustained attention” (Reed 2017, p. 11). This is precisely what Apeshit summons us to do with its interplay between motion and stillness, past and present. During its six-minute duration, the insertion of slow motion, hypnotic zoom in, close-up, and still frames that freeze the action allow us to pause and breathe. As the clock strikes twelve in both the opening (0:1–0:15) and closing sequences (5:51–6:0), the ghostly empty corridors of the world’s most visited museum set the tone. It is time for a new consciousness. Furthermore, Apeshit has the capacity to force us to pay attention to the details. We are drawn to look more closely to identify similarities and differences between Beyoncé’s tableaux and the referent artworks in the original context. As Reed summarizes in his examination of the living pictures genre,

Ordinarily you’d think that replicating images would discourage extended looking: once is enough. But having identified the tableau’s referent—Oh that’s Mona Lisa, Iwo Jima, Whistler’s Mother—we don’t suddenly lose interest. The instant of recognition is followed by a sustained regard, because it takes time to catalog points of likeness and lapse, of faithfulness to and difference from the original. We don’t simply look at tableaux vivants, then; we read them. We constantly make mental comparisons, measuring elements in the tableau against counterparts in the original.(Reed 2017, p. 52)

In order to “read” Apeshit ‘s tableaux vivants, a formal analysis that scrutinizes the artist’s choices of the visual components and compositional elements of the artwork—such as the color, proportion, contrast, camera angle, composition, lighting, costumes, and lines—will enable identification of underlying meanings. My point of focus will be a recurring stylistic feature in the video: the unclothed body. It was initially the bared bodies of the populations of Africa that helped foster the reductive association with the notion of a primitive and animalistic sexuality over centuries. In the following, I will examine two tableaux vivants representative of Beyoncé’s dual creative strategies to explore this motif of historical importance. In the first case study (3:53), my analysis will scrutinize the way Beyoncé transforms her semi-naked black body, assimilated to the sphere of nature by the dominant imperialist gaze, into an object of culture. With her sculptural body mimicked on the high art conventions of the nude genre, she is a contemporary Venus de Milo. Yet Beyoncé’s artistic investigation does not end at an inversion of a value system at risk of glorifying the ideologies that she denounces. In the second still image I wish to address (1:05), the artist alludes to another deity: the sacred figure of her African heritage. In Queen Bey’s choreography, regal silhouettes of semi-naked black dancers are partly pre-modern sacred ceremonial objects, partly objects of transcendental esthetic contemplation, and partly objects of erotic fascination—turning dominant schematic oppositions between the realms of nature and culture upside down in a truly syncretic fashion.

3. Bringing the Body Centerstage

Impassive and ceremonial, Beyoncé and Jay–Z stand still in front of the camera (3:53). The use of a low-angle perspective, and the zoom in of the camera from a full shot to a medium one, both magnify their presence. Their bodies stand out against a marble wall bathed in a dark blue and cold light. In this surrealist vignette, Beyoncé creates eye-catching correspondence between her persona and a foundational artwork in Western history located slightly on her right in the mid-ground: the Venus de Milo.

Aphrodite of Melos—often called by her Roman name, the Venus de Milo (circa 150–50 B.C.)—was discovered in Melos in 1820. The French naval officials based at that time on the Greek Island without hesitation snatched the vestiges of the marble statue. French King Louis XVIII donated the antique to the Louvre the following year in a strategic move to respond with the growing notoriety of its rival British neighbor. The British Museum had just taken hold of the treasured Parthenon Marble sculptures. Since then, the Venus has incarnated French cultural influence over the world. Prior to being an object of esthetic and intellectual refinement, the Venus had been an object of conquest and power. The fact that the details around its original context, attribution, and identification have been the subject of scholarly controversies has made the artwork more compelling than ever. The sensuality of her female form and her partial nudity have suggested a status dedicated to the worship of Aphrodite, the powerful Olympian Goddess of love, beauty, and fertility.

Today, the goddess is both an icon of popular culture and “an absolute emblem of classical beauty” (Arenas 2002, p. 35) that Beyoncé brings to life. The singer’s placid facial expression mimics the Venus’ impassive face. Only a closer look seems to detect a hint of defiance in Beyoncé’s gaze. Unlike the self-absorbed Venus whose head is slightly turned to her right side, Queen Bey defiantly stares back at us. With the exception of a few strategically placed wavy locks of hair, the singer’s golden mane is carefully hidden inside an oversized black scarf. Her hair style displays a similar rigor to the Venus’ curls which are “neatly parted at the center” (Arenas 2002, p. 36) and “gathered in a style one would almost call austere” (Arenas 2002, p. 36). The end result channels our interest to Beyoncé’s body. This sobriety of style is of course a modern interpretation. We need to remember that originally, make-up, jewelry and a polychromy often adorned the marble of Greek statues. Residual fixation holes in The Venus de Milo’s marble indicate the previous presence of a headband and earings.

In the original sculpture too, the sculptor drew the attention of the public to the Venus’ nudity. The rich nuances of lights and shades at play in the folds and creases of the carved drapery (Kousser 2005, p. 239) contrast with the model’s bared upper body. The falling apparel gives us a glance at her groin area. We are left to imagine what is concealed. Paradoxically, hiding parts of the represented figure has been a way for artists to reinforce their aura. Draperies and veils have embodied modesty and sensuality in a game of absence and presence (Zuffi 2010, p. 69). Both Beyoncé and the Venus de Milo bring back the potency and complexity of the physical presence of the body to the centerstage.

One major difference between Beyoncé and the marble goddess is the replacement of the drapery with a flesh-colored corset. Let us first concentrate on the symbolism of the corset before making sense of Beyoncé’s choice of the nude color. One could read the following message proudly advertized in the weblog of the French haute couture lingerie house Cadolle:

Thrilled and so honored to be featured in #Beyonce’s latest video #Apeshit. Our ‘Cage’ corset couldn’t look more stunning on such a divine figure. The #VenusdeMilo has now a serious competitor. #grateful #Icantbelievewemadeit #Cadolle #QueenB #TheCarters #loveiseverything #goddess #corset #HauteCouture #Louvre #Paris #Frenchlingerie #Cadollesculptsyourbody.(Cadolle 2018)

Herminie Cadolle founded the company named after her in 1887 to provide custom, tailored garments to weathy women. Mrs Cadolle quickly became famous for both her innovative design, which was considered to be the precursor of more confortable modern-day brassieres and for her prestigious clientele. Examples of her commissioned works have included the design of lingerie with secret pockets for dancer and convicted spy Mata Hari (Fontanel 2001, p. 77). Cadolle remains today a family-owned company managed exclusively by women.

At first glance, Beyoncé’s attraction to a corset from such a distinguished fashion house seems unsurprising. Hip Hop, Rhythm and Blues, and Pop music artists have had a long-lasting relationship with high fashion. Rhianna, filmed by Christian Dior luxury fashion house in the garden of Versailles (Cochrane 2015), and Willow Smith modeling for Chanel (2016 and 2017) are now part of the media landscape. We may read in this tendency a straightforward quest for social recognition from artists who have long been underated and from a black community which has been disenfranchized by structural inequalities for centuries. The lyrics of Apeshit fully support this argument when Beyoncé and Jay–Z sing in unison to anyone who will listen: “Stack my money fast and go (fast, fast, go)” and “I can’t believe we made it (this is what we made, made)”. Critics have regularly castigated Hip Hop’s culture of materialism in which lavish displays of wealth go hand in hand with capitalism—an analysis that sometimes misses the irony encoded in this performance of hyperconsumption (Murray 2004, p. 6).

Another obvious interpretation of Beyoncé’s predilection for a corset would be to read the apparatus in terms of its sexual desirability. The device enhances Beyoncé’s hips, bosom and buttocks while mimmicking the Venus’s curvacious body. Images of the corset bring to mind the risqué ambiance of a bourgeois boudoir, cleavage-revealing décolletages, and narratives of female submission. Valerie Steele notes that the erotic aura of the corset in the public consciousness does not just lie in the intricate ways a corset magnifies the body, but also in its “symbolism of lacing as surrogate for intercourse” (Steele 2005, p. 20). Another strong attraction was the controlling feature of the corset to discipline the female body. A man could lace his wife’s corset for the pleasure of observing “the waist contracting and the silhouette taking shape under his own hands. In this way, the corset allowed the man to shape a woman as he wished” (Barbier and Boucher 2010, p. 159). It was only in the 20th century that the corset fell from grace. Feminists, along with historians, doctors, and hygienists have unanimously denounced its harmful impacts on women’s health. Bell Hooks remembers fondly when women stripped “their bodies of unhealthy and uncomfortable, restrictive clothing”, (Hooks 2000, p. 31) as “a ritualistic, radical reclaiming of the health and glory of the female body” (Hooks 2000, p. 31) at the peak of second wave feminism. For women, to repudiate constrictive lingerie and incarnations of erotic femininity in 1968 was a way to protest for equal rights. Restrictive lingerie became a choice, not a social constraint. Chances are that Hooks, who famously described some aspects of Beyoncé as terrorist (Weidhase 2015) because of the potential detrimental impact of her sexualized perfomances on younger girls, would not approve of her wardrobe in Apeshit.

While considering that Hooks‘ points have some validity, I propose to add another layer of complexity. In the selected case study, there are more nuances in Beyoncé’s choice of a Cadolle corset than a rags to riches story and a tale of female coercion. What is also worthy of attention is the way Beyoncé resorts to the original meanings of the corset to transform the black female body into the embodiment of Western high culture—a site of phallic power and of artistic elevation—both exemplifed by the Venus de Milo.

4. The Corseted Body: Subverting Conventions of High Fashion

All the way down to her stilettoed heels, Queen Bey displays a statuesque presence that mirrors the silhouette of the charismatic and imposing Venus de Milo. While being the Western incarnation of female beauty, the Greek goddess could be described as phallic because she exhibits qualities traditionally attributed to men. Specifically, I am referring to strength and self control. Commentators regularly describe the Venus de Milo as a “forceful” (Curtis 2003, p. xi) figure, showing “serenity, assurance, and great comfort with her own beauty” (Curtis 2003, p. xii). The fact that “the ends of her mouth turn down slightly” (Curtis 2003, p. 213) earns her the reputation of being disdainful. One needs to imagine the deity’s “over-life-size” (Kousser 2005, p. 227) of six feet seven inches in height (Curtis 2003, p. xvii), dominating the gymnasium of Melos. She stands victorious after winning the Judgment of Paris as the fairest deity (Kousser 2005, p. 239), just for athletes to look up and admire her beauty.

Today, screens have replaced gymnasiums, but we can still peer at Queen Bey who stars on stage. When in the following sequences (5:03), Beyoncé dances next to an impassive Jay–Z who has one hand casually placed in the pocket of his white suit, the contrast between her rapid jerky movements and his immobilism is striking. We are a long way from the passive, weak, and sickly ideal of femininity conveyed by the corset in the popular imagination. In the 19th century, it was not uncommon for Victorian women to faint while, for instance, dancing at social functions (Steele 2005, p. 70). Here, Beyoncé’s corseted body has sexual agency. Jay–Z had better watch his step. She is a warrior wearing a contemporary armor.

Acording to historian Maurice Leloir (1951, p. 125), the corset in France was initially an item of men’s apparel. At the beginning of the 14th century, knights in Medieval France began wearing a pourpoint. The primary goal of this padded military clothing worn under armor was to protect the upper body during sword-fighting. These body-constraining garments gradually influenced the design of the civilian doublet in the 15th century. In a society that glorified wars, the doublet, which artificially built-up men’s torsos and delineated their waists, represented the pinnacle of masculine elegence for aristocratic men. It is important to really grasp this masculine military origin of the corset. Firstly, it conveys this martial power on which Beyoncé and other precursors had earlier drawn. Steele records the revival of the corset in the underground fetishist pornographic scene of the late 1970s, when “corsetry was associated with the image of the powerful Phallic Woman” (Steele 2005, p. 165). In sado-masochist roleplays, the rigid shell was for the corseted wearer either a tool of emancipation or of alienation. It was an instrument of sexual humiliation in tightlacing scenarios, or an instrument of domination that gave to the controlling player a thrilling sense of (self) control. Secondly, the medieval corset was a major break in the apprehension of the French body—a body crafted by a rigid device to become an idealized cultural artifact. Here is how Bruna explains this cultural shift:

Rather than revealing the shape of the body by following their labyrinths of curves and countercurves, these garments often suggested different shapes by falsifying the body supporting them. The garment removes a bit here, adds a bit there; in short it creates a new body. Thus the natural body no longer exists; what we have is a cultural body emerging through a silhouette characteristic of a moment in time.(Bruna 2015, p. 32)

While the concept was not completely new, the “idea of the body as sculpture” (Bruna 2015, p. 32) took a new dimension with the medieval body. This paradigm was to such an extent that calls arose against men who dared to alter the original perfection of the natural body considered to be the work of the divine creator. The emergence of the corset in the European court culture of the first half of the 16th century further evolved the idea of amending the silhouette. Aristocratic women and girls progressively added more rigid materials, such as buckram and whalebone, into their cloth bodices (Steele 2005, pp. 6–7). The goal of this constrictive posture that dramatically altered the appearances of the hips, the waist, and the bust, was to create a bodily esthetic distinct from less entitled populations. Until the invention of the mechanical corset in 1823 that allowed women to lace and unlace their corsets alone (Fontanel 2001, p. 49), tightening a corset required the help of a servant. Because of the way the corset limited physical mobility, it signaled a life of idleness and wealth. For the laboring class, it was difficult to perform physical labor while wearing such a restrictive device, let alone afford the price of the refined material. Even in the 19th century, when corsets became more widespread during the democratization brought about by the industrial revolution, they could cost between twenty to forty French francs (approximately $140.00 in today’s currency) (Fontanel 2001, p. 47). Country women had no choice other than to wear a corselet, which differed greatly from the garment worn by the ruling class. This humblest version of the corset needed to be tightened from the front, so that dressing up did not require assistance (Fontanel 2001, p. 39). Working women laced the piece of material loosely to comfortably perform harsh daily activities. Crucially, corselets did not mold the human natural forms. In her formal analysis of Van Gogh’s drawings of peasant women at work (1885), Griselda Pollock theorizes the dichotomy between the “sculpted landscape” (Pollock 1999, p. 47) of the corseted lady and the uncontrived torso of the working class. In the bourgeois erotic imagination, the physical figure of the female peasant forced to bend—thus, indecently exposing her buttocks—and to be semi-naked, correlated strongly with the notions of animality and bestiality. In summary, the corset was deeply linked to the idea of sublimating the aristocratic body as a cultural object of esthetic, but also of moral and sexual values. The aristocratic body was not just the work of God. It was also a work of art for the pleasure of the eye and the elevation of the soul.

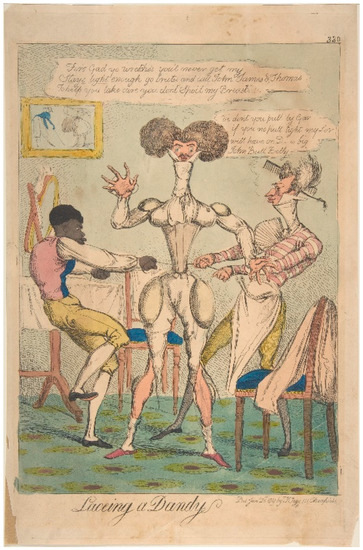

To transform the body into an abstraction was mainly reserved to a classed but also a racially defined elite. From the archetypal Mammy (actress Hattie McDaniel), pulling Scarlett O’Hara’s (actress Vivien Leigh) corset as hard as she could in the movie Gone with the Wind (adapted in 1939 by Victor Fleming from Margaret Mitchell’s novel of the same name written in 1936), to caricatural anonymous prints such as Tight Lacing, or Fashion before Ease (circa 1777) (Figure 3) and Lacing a Dandy (1819) (Figure 4), representations of (black) servants submissively lacing-up the entitled body have abounded.

Figure 3.

Jon Collet, Tight Lacing, or Fashion before Ease (1777). Paper. Satirical print published by Bowles and Carver. The British Museum. Source: https://www.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/collection_object_details/collection_image_gallery.aspx?assetId=142571001&objectId=1639535&partId=1.

Figure 4.

Anonymous, Lacing a Dandy (1819). Hand-colored etching. Satirical print published by Thomas Tegg. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Source: https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/384283.

In this new light, we could read in Beyoncé’s vignettes, a transgressive role reversal of what Patricia Hill names the “controlling images” (Hill 2000, p. 69) of black women—and more specifically, of the figure of the “mammy”. Hill (2000, pp. 69–93) details how a range of interrelated stereotypical representations of black womanhood rooted in the African American history of slavery have reinforced the subjugation of black women. The history of the controlling images began with the mammy (Hill 2000, p. 72). The pervasive representations in the social fabric of faithful servants have legitimized the limitation of black women to domestic service from the time of slavery onwards. Southern mammies were supposedly as deferent as they were content, completely ready to serve their white family better than their own. The mammy was “an ideal slave” (White 1985, p. 58), an idealized view entrenched in the cult of domesticity, maternity, and morality (White 1985, p. 58). More an ideological construct that blossomed after the Civil War than a concrete reality, the “mythology” (White 1985, p. 54) of the mammy offered a warm and comforting image of the harsh truth of slavery and its daily reality. Her physical strength, robust body, and effectiveness was a converse image to the dainty, passive, and decorative models of white femininity. In Mitchell’s description of the mammy’s character in her novel, Mammy was “a huge old woman with the small, shrewd eyes of an elephant” (Mitchell 1936, pp. 22–23) and could “move with such savage stealth” (Mitchell 1936, p. 546). She had the “sadness of a monkey’s face” (Mitchell 1936, p. 415) and “monumental, sagging breasts” (Mitchell 1936, p. 545). We need to read the animalization of Mammy and of her large shapeless body in contrast to the valorization of Scarlett’s culturally constrained silhouette.

Thus, Beyoncé’s corseted and stiffened body standing determinedly in the Louvre is already full of political innuendos. Even so, Queen Bey does not stop at the subversion of high-fashion protocols through the use of the corset. The artist renforces the idea of the black female body as a work of high art by transgressing the female nude genre embedded in the conventionalized depictions of Greco-Roman divinities.

5. The Unclothed Body: Subverting Conventions of High Art

Beyoncé’s choice of the nude color corset immediately refers to the historically charged notion of nakedness. The back-blue light that cloaks her body in semi-obscurity enhances the impression of complete nudity. Queen Bey presents a striking example of what Kenneth Clark calls “the nude” (1959). Clark theorizes two ways of presenting the unclothed body. On one side, there is the notion of being “naked” which indicates a deep shame rooted in the Judeo-Christian tradition. It is after eating the apple from the forbidden Tree of Knowledge that Adam and Eve became aware of their nudity and sexual craving. The price to pay for their disobediance of God was to leave the Paradise. For colonialists, missionaries, scientists and traders, the nudity of the native populations in Africa represented a troubling spiritual dysfunction (Levine 2008, p. 191). In this ethnocentric worldview framed by the original sin, they never considered the “requirements of a tropical climate” (White 1985, p. 29) when interpreting near nakedness to “lewdness” (White 1985, p. 29). As Philippa Levine rightly expresses, the “native was signified by near-nakedness and animalism, the white by proper clothing and stout weaponry that could be turned against all manner of wild animals, the local human population included” (Levine 2008, p. 215). Clothing delimited the boundaries between bestiality and humanity, savagery and civility.

The semi-nudity of the female native especially clashed with the Western middle-class model of chastity and prudery. This lack of sexual modesty could be synonymous only for Westerners with loose sexual customs and by implication, promiscuity. They never contemplated the possibility that the notions of respectability, beauty, and nudity could relate differently in other cultural contexts. Thus, visitors have largely ignored the scope, roles, and refinement of natural adornments and body modifications in the native cartography of desire. Hans Silvester’s (2009) contemporary photographs of the Surma people in the Omo valley of Ethiopia for instance, illustrate how, in the hands of these communities, nuts, roots, flowers, bones, feathers, fruits, and snail shells transform into jewelry and accessories. The body becomes a “sculptural surface” (Silvester 2009, p. 3) on which to paint abstract motifs with natural pigments. Drawing of the example of the Motuan people in Papua New Guinea, Macintyre and MacKenzie observe that where “nakeness is commonplace, adornement is the crucial expression of beauty” (Macintyre and MacKenzie 1992, p. 163). Motuan women only exposed the tattoos that ornated their thighs and buttocks at specific ceremonial occasions. It was the patterned body and not its bareness that conveyed sexual desirability and marriageability.

The fact that Westerners equated the apparent, in their eyes, absence of female modesty in Africa with licentious and bestial desires is encapsulated in the story of Saartjie Baartman (also Sarah, Sara and Saartje among other spellings due to the lack of any verifiable record of her original name). Baartman (circa 1790–1815) traveled from Capetown to Liverpool in 1810. She strived for the brighter future that had been promised by surgeon and Chip’s exporter of museum specimens Alexander Dunlop (Qureshi 2004, p. 235) and showman Hendrick Cezar. Barely off the boat, Dunlop tried unsuccessfully to “sell his share in the ‘Hottentot’ as well as the skin of a giraffe” (Sharpley-Whiting 1999, p. 18) to the director of the Liverpool Museum in London. While Baartman aspired to demonstrate her artistic skills, Dunlop and Cezar, who exhibited her in the London’s thriving freak show scene, had other expectations. So did the Victorian public. They were not longing for Baartman’s performance but for her curvaceous body. It was not enough to theorize black female sexuality as animalistic in the collective imagination. One needed concrete proof. Baartman’s hypertrophied vaginal labia—called at the time the “Hottentot apron”—and enlarged buttocks were typical of the physiognomy and body modifications of the Khoikho tribe. For the Victorian audience, these physical specificities were the “external signs” (Gilman 2002, p. 122) of black women’s “‘primitive’ sexual appetite” (Gilman 2002, p. 122). In order to emphasize her bodily features, Baartman had to wear a tight costume in the color of her complexion (Strother 1999, p. 43). If decorum prevented her manager from exhibiting Baartman fully naked, her attire did not leave much to the imagination. Even fully clothed, Baartman had to appear “naked”. In this highly sexually exploitative scenario, Baartman’s (un)clothed body refers to Clark’s interpretation of nakedness. It carries the feelings of “embarrassment” (Clark 1959, p. 23) and defenselessness. Beyond reasons of salacity, this Victorian conceptualization of black femininity reassured the crowd of their sexual and moral superiority while conveniently justifying calls for colonial subjugation.

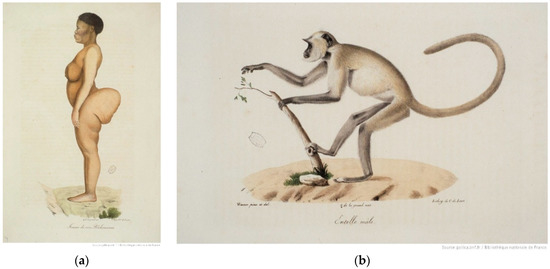

Another example that can tell us a great deal about the positioning of Baartman in the collective imagination is the scientific interest that her body generated. In 1815, she accepted to pose nearly naked for the sake of science at the French Muséum d’Histoire Naturelle in Paris. Zoologists Etienne Geoffroy Saint–Hilaire’s and Georges Cuvier scrutinized her physiognomy along with artists Jean–Baptiste Berré, Léon de Wailly, and Nicolas Huet, who sketched her figure. In the watercolors (Figure 5) that illustrate (Saint-Hilaire and Cuvier 1819) Volumes One and Two of the Histoire Naturelle des Mammifères (The Natural History of Mammals), Sadiah Qureshi notices that

Cuvier’s descriptions of the illustrations also positioned Baartman closer to the animal in the evolutionary scale by comparing her with the mammals pictured in the book. For the zoologist, Baartman’s “brusque et capricieux” (sudden and unpredictable) (Cuvier 1824, p. 5) movements suggest those of monkeys, and her way of protruding out her lips are supposedly very similar to what he had previously observed in orangutans. While Baartman’s nickname was the “Hottentot Venus”—a term that encapsulates the feeling of attraction and repulsion of the public—her image never adorns the walls of the French temples of culture. Instead, Cuvier dissected Baartman’s body after her death in 1815. Her skeleton and a full plaster cast of her figure were exhibited in the Musée de l’Homme in Paris until the 1970s (Qureshi 2004, p. 233), her brain and genitals conserved in a jar. Sharpley–Whiting’s comment that even “in Baartman’s nakedness, Cuvier had yet to decipher her body, to undress the body” (Sharpley-Whiting 1999, p. 27) highlights the deep racial, sexual and medical fascination that Baartman’s body exerted over the French psyche.Instead of portraying a classical pose, the artist presents views framed similarly to the other mammalian specimens in the volume and which are analogous to the anterior and lateral profiles used in zoological illustration. The delicate colouring is clearly intended to be realistic; details such as the hair, veining of the areola tissue, and nails contribute clinical precision. Minimal scenery hints at a geographical location without interfering with the human/animal subject.(Qureshi 2004, p. 242)

Figure 5.

Wermer, illustrations for Histoire Naturelle des Mammifères (1819). (a) Depiction of Baartman with the caption “Femme de race Bôchismanne”. (b) Depiction of a male monkey with the caption “Entelle mâle”. Text Etienne Geoffroy Saint–Hilaire and Frédéric Cuvier. Bibliothèque National de France (Gallica.bnf.fr). Source: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b2300295r?rk=107296;4.

In contrast to the disparaged image of nakedness, Clark opposes the notion of being “nude” (Clark 1959, p. 23) ingrained in the classical art. The visual repertoire of the Western female nude has its source in the glorification of Greco-Roman undraped divinities (Squire 2011, p. 68). From the 15th century onward, the female nude as an object of esthetic and intellectual value has progressively replaced the male nude associated with God’s perfection. A revival of the Ancient World during the Renaissance contributed to the formation of this new art form. The nude culminated in the 19th century with the consecration of the notion of “fine art” in opposition to a more decorative and utilitarian art. Since then, coded visual tropes and instances of legitimization have policed the thin line between object of obscenity and artistic merit, body and mind, nature and culture in the definition of who and what constitute the ideal nude.

In Beyoncé’s radical reimagining of the dehumanized black female figure, her semi-clothed figure incarnates the splendor of the cultural body. She displays what Clark calls a “body re-formed” (Clark 1959, p. 23), blessed with insolent youth and physical strength. The nude stands against an unruly natural order. It denies childbirth—three in the case of Beyoncé—and the finitude of life. Beyoncé’s formidable figure is a brilliant demonstration of Clark’s description of the “balanced, prosperous, and confident” (Clark 1959, p. 23) nude. Queen Bey embodies a glorious cultural ideal. She is a modern Venus de Milo—a point made by Cadolle on the company’s social network Twitter when stating that “the #VenusdeMilo has now a serious competitor”. The discredited black body can play in the same league as the mother of all the Western nudes.

Queen Bey is using a similar artistic strategy to the one at play with the corseted body. After subverting the image of the “mammy”, Beyoncé plays with another “controlling image” (Hill 2000, p. 69): the “jezebel”. The supposed sexual promiscuity of African women illustrated by the story of Baartman has formed the basis for another pervasive stereotype, the figure of the jezebel. Unlike the asexual mammy too busy with her domestic duties, the jezebel seems to not be able to satiate her voracious sexual nature. This stereotypical image was twofold. First, it helped justify the cost efficiency of forced procreation by women in order to increase the slave labor force. Women “were ‘breeders’—animals, whose monetary value could be precisely calculated in terms of their ability to multiply their numbers” (Davis 1983, p. 10). Second, the image of a sexually loose woman always ready for intercourse provided grounds for the perpetuation of sexual violence perpetuated by white masters (Hill 2000, pp. 81–82). Angela Davis (1983, p. 10) astutely emphasizes that the rape of women working in tobacco, cane, and sugar fields was not a biological urge but another tool of domination. Both depictions of the mammy and the jezebel have policed and exploited the sexuality of black women for prurient and economic interests. They are the two sides of the same coin. Thus, one of the strengths of Queen Bey’s cultural and monumental body is the dismissal of denigrated depictions of black women ranging from “carnal to maternal” (White 1985, p. 46), that have saturated the Europeen visual landscape.

This role reversal is in the artistic legacy of black female artists such as Mickalene Thomas. Thomas’ erotically charged multimedia installation, Me as Muse, merges a patchwork of depictions fluctuating from Western canonical nudes to the portrait of the artist unclothed in a classical pose, and the statuesque physique of model, singer and trendsetter Grace Jones. The artist’s fragmented imagery and the broken voice of the narrator give us a glance not only at the struggle black women have faced over time but also at the scars left in their current cartography of desires. Renée Cox has been another precursor in creating an empowering corpus of images through installation art and staged photography. The confidence of Cox, standing completely naked with the exception of her black spike heeled shoes in her black and white auto-portrait The Yo Mama (1993), immediately recalls Beyoncé’s defiant posture next to the Venus de Milo. With Missy at Home (2008), Cox is not short of humor when she impersonates a wealthy collector of her own work. She sits straight-up—a rigid posture that implies a strict control of the body—on the sofa of her living room. A white servant is busy serving her with deference. The groomed poodle dog as compliant as Cox’s housekeeper, and the fluffy lamb fleece pillow cover casually placed on the couch, are more than social status symbols. They also express the control of culture over a domesticated nature. Another interesting example is Cox’s photographic vignette Baby Back (2001), in reference to Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres’ painting La Grande Odalisque (1814). The artwork depicts a classical reclining nude with a twist. In the review of Cox’s work, Deborah Willis pays attention to the artist’s sexual agency in the mise-en-scène:

She shows enough of her face to guide the viewer to her long locks, strikingly round bottocks, and red patent leather heels and then grabs attention with the bullwhip she holds. A yellow rose, possibly from an appreciative lover, sits at the edge of the frame on the floor. Cox like Thomas and Williams explores the sexual fantasies so often revealed in nineteenth-century painting, but she places the control in the woman’s hand. The empowered odalisque is no longer the sex slave but the one who determines her own pleasure. Cox takes artistic license and turns desire upside down. The large photograph (100 × 144 inches) recalls the scale of the original painting and at the same time critiques the representation of black women in the history of art.(Willis 2014, p. 206)

It would, however, be incorrect to reduce the work of Beyoncé—and of her artist peers—to a straightforward reversal game. A simplistic “cut and paste” approach would be a celebration of the values of the dominant system. Beyoncé does not just dare to confront Western classical art by displaying her cultural body. She recreates majestic examples of original nakedness. It is when Beyoncé fills the room with semi-naked dancers reminiscent of the sacred figure of her African heritage that she offers a true syncretic language. The result is a celebration of what Janell Hobson calls the “collective black body politic” (Hobson 2018, p. 178). From Bootylicious (2001) that exalts curvaceous black female bodies epitomized by Baartman (Hobson 2018, pp. 141–78) to Apeshit, Beyoncé has yearned to write a “shared history of racial and sexual objectification and embodied resistance” (Hobson 2018, p. xiii). Turning to African art is a way for Queen Bey to remind the white social order that she is above all a woman proud of the beauty and specificities of her black body. At the zenith of her career in the Louvre, her true allegiance is to her transnational black community.

6. Original Nakedness: Reimagining a Space of Possibilities

A close analysis of one of the sequences (1:05) that opens the video clip could be useful to discern how Beyoncé challenges a simplistic binary opposition between the realms of culture and nature to create new possibilities. Eight black female dancers in nude-colored leotards invest the corridors of the Louvre. Unlike the Cadolle’s corset, their underwear comfortably fits the natural shapes of their bodies’ contours without restricting their freedom of movement. A backlighting produces a contre-jour that transforms their figures into monochromatic silhouettes. The overall effect is to relegate the paintings on the walls to mere background. Reduced to a two dimentional shape, the dancers become an abstraction—a collection of sculptures placed on pedestals for our scopophilic pleasure. The repetition of body shapes and their formal simplicity produce a unified whole. The dancers’ spatial positions define two orthogonal lines. They recede to a vanishing point to convey a feeling of continuity. This triangular pathway accentuates the sense of a strong visual organization.

Beyond the precision of its esthetic features and its sense of connectedness, what is striking in this scenography is the bodily positions of the dancers. With their knees flexed and arched backs, they are live versions of some of the stolen native objects exhibited as works of art in Western museum (Figure 6). In the pre-modern sculpural tradition, carved figures covered a large spectrum of possibilities. They could be decorative and functional, dedicated to honor kings and queens, used in funerary rites, and receptacles of spiritual power. In the latter, objects of worship were essential for the social cohesion of the community. They could attest to the ongoing presence of the ancestors of deceased members, and act as mediators between the living and spiritual entities. People turned to them for reasons as diverse as resolving a conflict in the community, calling for protection, curing a sickness, or finding solace in the face of adversity. Objects of worship encapsulated different forms of knowledge essential to their ecosystems of origin. Far from being a homogenous topography, each geographical area had its own rituals and stylistic features. Their refinement was such that when German explorer Leo Frobenius collected Ife objects of Ancient Nigeria for European museums in the early 20th century, he could not envisage “like many others of his day” (Schildkrout 2009, p. 4) that they “were of African origin and theorized that this great art was evidence of the lost Atlantis of the Greeks” (Schildkrout 2009, p. 4).

Figure 6.

Anonymous. Side (a) and back view (b) of a female figure from a reliquary ensemble (19th–20th century). Wood and metal. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Source: https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/310870.

From the 19th century onward, the colonialist order and a rising interest in ethnography have justified the looting of African artifacts on a large scale while depriving the countries of origin of their cultural heritages. In the report Witness to History: A Compendium of Documents and Writings on the Return of Cultural Objects, Alain Godonou stresses that today “90 percent to 95 percent of African heritage is to be found outside the continent in the major world museums” (Godonou 2009, p. 61). By re-contextualizing, classifying, and cataloguing these objects with new official narratives and scenographies, Western museums have asserted their power to control their meanings in a hierachical perception of the world. Artifacts lost their properties in the process of becoming objects of scientific inquiries. They were stripped of their affiliation to their communities and of the performative rituals that animate their abilities.

With the advent of modern art, a new shift occurred early 20th century. African artifacts became objects of esthetique transcendence. The wooden carved sculpture from a Fang (Oak group) reliquary ensemble (Gabon and Equatorial Guinea), which is today exhibited in the American Metropolitan Museum of Arts in New York City (MET), exemplified this transformation (Figure 6). In the museum’s accompanying text concerning the relic, one can read that Fang sculptures tremendously impressed European collectors in the 1920s (Metropolitan Museum of Art 2019). Artists praised their abstractions of the human form. Before its acquisition in 1961 by the director of the Museum for Primitive Art Robert Golwater, the figure of this reliquary ensemble was the property of French artist André Derain. It is most interesting to know that French painter Maurice de Vlaminck “showed an African sculpture to Derain and said that he found it to be ‘almost as beautiful as the Venus de Milo’. Derain responded that it was in fact ‘as beautiful as the Venus de Milo’. The two then showed it to Picasso, who reputedly deemed it ‘more beautiful than the Venus de Milo’” (Metropolitan Museum of Art 2019).

For these artists mainly interested in the formal and sensual qualities of the objects, it was not considered important to know that they had previously had a life of their own. In the 19th century, Fang reliquary figures such as the one on display in the MET were devoted to the Bieri ancestral cult. They were positioned on top of bark containers to carefully guard the sanctified relics of preeminent ancestors. In the museal space, the carved figure stands today alone, severed from the crate she was supposed to safeguard. We need to acknowledge the violence at work in the heart of these practices. By conceptualizing sacred figures as static artistic objects, Western museums have partially amputated them from their deep inner meanings in an inexorable way. In this new light, we could interpret the selected sequence in Apeshit as the re-enactment of a ritualistic ceremony that gives the operative power back to sacred carved sculptures. The objects/subjects incarnated by semi-naked dancers again exude the sense of temporal continuity and cohesiveness of their roots. They are as “alive” as in the days they were animated with primary forces by collective rituals and knowledgeable individuals. Queen Bey presents to us a syncretic mode of display and activation of the female figure. Her metaphorical carved sculptures are both contemplative artworks in the Western definition of high culture, Venus on their own terms, and traditional objects of sacred performances.

7. Conclusive Notes

While Beyoncé does not address the tight links between the imperialism she denounces and the capitalism that she indirectly celebrates, Apeshit is nonetheless a complex and politically charged work. It is my hope that other scholars will keep investigating the layers of meaning embedded in this rich text. Findings in this paper confirm my original claim of a syncretic language in which the erotic and the esthetic are never far from the politic. Beyoncé looks back and forth to lace past and present and the contested notions of nature and culture. The conceptual and formal force of her work is in the dismantling of spatial and temporal borders.

The venture is not without its difficulties. When the British newspaper The Sun (Wootton 2016) spread unfounded rumors alleging that Beyoncé was planning to star in a filmic interpretation of Baartman’s life, public outrage ensued. Reactions varied from “African Americans puzzling over why someone with the superstar status of Beyoncé would ‘demean’ herself in taking on such a sexualized (and pathologized) role, to South Africans expressing outrage that Baartman, reconfigured as ‘mother of the nation’, would be misrepresented by an iconic black sex symbol from the U.S.” (Hobson 2018, p. 141). While the idea of Beyoncé incarnating Baartman raises serious ethical questions and would have necessitated close attention to often unspoken power dynamics within the African diaspora, the result may well have been a further example of Beyoncé’s syncretic language.

By positioning the black body in relation to larger economic, political, geographic, and social forces, Queen Bey proposes with Apeshit a portrayal of black women in their complexity, sensuality, and humanity. The inspiration for her work is grounded in a long history of trauma inflicted upon the black female body. From slavery onwards, black women have been dispossessed of their corporality and desires to serve sexual and economic interests. Popular visual representations—such as the “controlling images” (Hill 2000, p. 69) of the mammy and the jezebel—and high art have played a pivotal role in naturalizing imperialistic logics of subjugation and colonization.

Yet black women have never been passive in facing the odds. They have strived to draw new sexual, esthetic, and social landscapes. In the legacy of African American female artists, Apeshit is a visual and sensual manifesto that provides new ways of interrogating the imperial past, of challenging the present, and of foreseeing the future. Beyoncé investigates the historically charged notion of nakedness to draw a critical reimagining of museal practices. With its confronting role reversals and its syncretic vocabulary, Apeshit manages, in a few snapshots, to tackle the tension between two complementary dynamics. On one side, there has been the erasure and dehumanization of the black female body in European canonical works. And on the other side there has been the pillage of a cultural heritage in a process of “intentional alienation and deculturation of subordinated populations whose psychological equilibrium has been broken” (Sarr and Savoy 2018, p. 7). The two forces have worked hand in hand. Art historian Bénédicte Sarr and writer Felwire Savoy note similarities between strategies of dehumanization, such as rape in times of war and occupation, with the looting of artifacts. Without their cultural heritage, communities feel deprived of a “part of the foundation of their humanity” (Sarr and Savoy 2018, p. 8) such as “their spirituality, creativity, transmission of knowledge” (Sarr and Savoy 2018, p. 8).

On this subject, it is thought-provoking to see how Beyoncé’s creative production has anticipated the crucial issue currently trending: the question of the restitution of stolen African cultural heritage. The debate is not new. Countries such as Nigeria have appealed to France for the repatriation of their cultural heritage taken without consent during the colonial era for more than five decades (Sarr and Savoy 2018, p. 17). They have faced contemptuous indifference and resistance as the sole responses. The subject took a new dimension when French president Emmanuel Macron expressed his willingness to return to African nations items that are rightfully theirs on 28 November 2017. Macron’s speech at the University of Ouaga 1 in Burkina Faso’s capital Ouagadougou enhanced the momentum. Macron commissioned an investigation written by Savoy and Sarr advocates for an “opening up for the signification of the objects” (Sarr and Savoy 2018, p. 2). In this major report that has yet to be concretely implemented, they raise the importance for African nations of undertaking a process of “self-reinvention” of the returned objects (Sarr and Savoy 2018, p. 32). Savoy and Sarr give the example of the National Museum in Mali. A selection of objects already exists in a plurality of ecosystems: on display at the museum and on loan in the community for ritual use. In this fluid framework, the object could “fulfill a different function at each site (pedagogical, memorial, creative, spiritual, mediator, etc.)” (Sarr and Savoy 2018, p. 33).

Because displaced objects have “incorporated several regimes of meaning” (Sarr and Savoy 2018, p. 87), Savoy and Sarr call for them “to serve as mediators of a new relationality” (Sarr and Savoy 2018, p. 87). In this framework, the items become the support for “another relational ethics” (Sarr and Savoy 2018, p. 87) to “initiate a new economy of relations whose effect will not be limited to cultural spaces or those of museographical exchanges” (Sarr and Savoy 2018, p. 88). What is really at stake is a new balance between the global north and the global south. This concept of “new relationality” is fully present in Beyoncé’s corporality, sensuality, and creativity. In the likeness of the objects she re-enacts, Queen’s Bey syncretic vocabulary does not have a fixed meaning. Rather, it carries a stratification of significations. By doing so, Beyoncé’s creative work maps different scenarios, traces possible futures, and enriches the collective imaginaries at large.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Arenas, Amelia. 2002. Broken: The Venus de Milo. Arion: A Journal of Humanities and the Classics 9: 35–45. [Google Scholar]

- Barbier, Muriel, and Chazia Boucher. 2010. The Stories of Women’s Underwear. New York: Parkstone International. [Google Scholar]

- Bruna, Denis. 2015. Fashioning the Body: An Intimate History of the Silhouette. New York: Bard Graduate Center. [Google Scholar]

- Cadolle Loves. 2018. Available online: https://www.cadolle.com/en/actualites/beyonce-b3.html (accessed on 4 April 2019).

- Clark, Kenneth. 1959. The Nude: A Study in Ideal Form. New York: Doubleday Anchor Books. [Google Scholar]

- Cochrane, Lauren. 2015. Rihanna Becomes Dior’s First Black Campaign Star. The Guardian. May 14. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/fashion/2015/may/14/rihanna-becomes-diors-first-black-campaign-star (accessed on 8 August 2019).

- Curtis, Gregory. 2003. Disarmed: The Story of the Venus de Milo. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. [Google Scholar]

- Cuvier, Georges. 1824. Femme de Race Boschismanne. In Histoire Naturelle des Mammifères. Edited by Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire and Frédéric Cuvier. Paris: Belin, A. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, Angela Y. 1983. Women, Race & Class. New York: Vintage ebook. [Google Scholar]

- Fontanel, Béatrice. 2001. Support and Seduction: The History of Corsets and Bras. Translated by Willard Wood. New York: Abradale Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gilman, Sander. 2002. The Hottentot and the Prostitute. In Race-ing Art History: Critical Readings in Race and Art History. Edited by Kymberley N. Pinder. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Godonou, Alain. 2009. Museums, Memory and Universality. In Witness to History: A Compendium of Documents and Writings on the Return of Cultural Objects. Edited by Lyndel V. Prott. Paris: United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, Patricia Collins. 2000. Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness and the Politics of Empowerment. New York and London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hobson, Janell. 2018. Venus in the Dark: Blackness and Beauty in Popular Culture. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hooks, Bell. 2000. Feminism is for Everybody: Passionate Politics. Cambridge: South End Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jamieson, Amber. 2016. West Virginia County Worker Fired for Calling Michelle Obama an ‘Ape in Heels’. The Guardian. November 15. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2016/nov/15/michelle-obama-ape-in-heels-post-west-virginia-worker-fired (accessed on 15 May 2019).

- Knowles-Carter, Beyoncé. 2019. Homecoming: A Film by Beyoncé. Los Gatos: Netflix. [Google Scholar]

- Kousser, Rachel. 2005. Creating the Past: The Vénus de Milo and the Hellenistic Reception of Classical Greece. American Journal of Archaeology 109: 227–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Leloir, Maurice. 1951. Dictionnaire du Costume et de ses Accessoires des Armes et des Etoffes des Origines à nos Jours. Paris: Librairie Gründ. [Google Scholar]

- Levine, Philippa. 2008. States of Undress: Nakedness and the Colonial Imagination. Victorian Studies 50: 189–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macintyre, Martha, and Maureen MacKenzie. 1992. Focal Length as an Analogue of Culture Distance. In Anthropology and Photography, 1860–1920. Edited by Elizabeth Edwards. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- McGrath, Elizabeth. 1992. The Black Andromeda. Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 55: 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metropolitan Museum of Art. 2019. Figure from a Reliquary Ensemble: Seated Female, 19th–Early 20th Century. Available online: https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/310870 (accessed on 5 May 2019).

- Mitchell, Margaret. 1936. Gone with the Wind. New York: The Macmillan Company. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, Derek Conrad. 2004. Hip-Hop vs. High Art: Notes on Race as Spectacle. Art Journal 63: 4–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murrell, Denise. 2018. Posing Modernity: The Black Model from Manet and Matisse to Today. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Musée d’Orsay. 2019. Black Models: From Géricault to Matisse. Available online: https://www.musee-orsay.fr/en/events/exhibitions/in-the-museums/exhibitions-in-the-musee-dorsay-more/article/le-modele-noir-47692.html?tx_ttnews%5BbackPid%5D=254&cHash=1135cf8ff6 (accessed on 13 April 2019).

- Pollock, Griselda. 1999. Differencing the Canon: Feminist Desire and the Writing of Art’s Histories. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Qureshi, Sadiah. 2004. Displaying Sara Baartman, the “Hottentot Venus”. History of Science 42: 233–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randanne, Fabien. 2018. «Apeshit»: Dans le clip, Beyoncé et Jay–Z «se mettent sur un pied d’égalité» avec la Joconde. 20 Minutes. June 4. Available online: https://www.20minutes.fr/arts-stars/culture/2291923–20180618-apeshit-clip-beyonce-jay-z-mettent-pied-egalite-joconde (accessed on 20 February 2019).

- Reed, Arden. 2017. Slow Art: The Experience of Looking, Sacred Images to James Turrell. Oakland: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Saint-Hilaire, Geoffroy, and Frédéric Cuvier. 1819. Histoire Naturelle des Mammifères. Paris: Lasteyrie, C. de. [Google Scholar]

- Sarr, Felwine, and Bénédicte Savoy. 2018. The Restitution of African Cultural Heritage: Toward a New Relational Ethics. Paris: Présidence de la République. [Google Scholar]

- Schildkrout, Enid. 2009. Ife Art in West Africa: An Introduction to the Exhibition. In Dynasty and Divinity Ife Art in Ancient Nigeria. Edited by Henry John Drewal and Enid Schildkrout. New York: Museum for African Art. [Google Scholar]

- Sharpley-Whiting, Tracy Denean. 1999. Black Venus: Sexualized Savages, Primal Fears, and Primitive Narratives in French. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Silvester, Hans. 2009. Natural Fashion: Tribal Decoration from Africa. London: Thames & Hudson. [Google Scholar]

- Squire, Michael. 2011. The Art of the Body: Antiquity and its Legacy. London and New York: I. B. Tauris. [Google Scholar]

- Steele, Valerie. 2005. The Corset: A Cultural History. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Strother, Zoë. 1999. Display of the Body Hottentot. In Africans on Stage: Studies in Ethnological Show Business. Edited by Bernth Lindfors. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. [Google Scholar]

- The Carters. 2018. Apeshit. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kbMqWXnpXcA (accessed on 18 March 2019).

- The Louvre. 2019. 10.2 Million Visitors to the Louvre in 2018. Paris. Available online: https://presse.louvre.fr/10-2-million-visitors-to-the-louvre-in-2018/ (accessed on 15 May 2019).

- Weidhase, Nathalie. 2015. ‘Beyoncé Feminism’ and the Contestation of the Black Feminist Body. Celebrity Studies 6: 128–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, Deborah Gray. 1985. Ar’n’t I a Woman?: Female Slaves in the Plantation South. New York: Norton. [Google Scholar]

- Willis, Deborah. 2014. Contemporary Photography: (Re)presenting Art History. In The Image of the Black in Western Art: The Twentieth Century. Edited by David Bindman and Karen C. C. Dalton. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Willsher, Kim. 2013. French Magazine Faces Legal Inquiry over Racist Slur against Politician. The Guardian. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2013/nov/13/french-magazine-racist-far-right-minute-crafty-monkey (accessed on 1 June 2019).

- Wootton, Dan. 2016. Beyonce Has Bot Her Eyes on Winning an Oscar for Film About Lady with Giant Rear. The Sun. January 2. Available online: https://www.thesun.co.uk/archives/bizarre/934423/beyonce-has-bot-her-eyes-on-winning-an-oscar-for-film-about-lady-with-giant-rear/ (accessed on 28 July 2019).

- Zimmer, Ben. 2018. Going “Apes––t”. Slate. June 19. Available online: https://slate.com/culture/2018/06/apeshit-etymology-the-history-of-the-phrase-behind-beyonce-and-jay-zs-new-single.html (accessed on 4 June 2019).

- Zuffi, Stefano. 2010. Love and the Erotic in Art. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum. [Google Scholar]

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).