“Our Self-Undoing”: Christina Rossetti’s Literary and Somatic Expressions of Graves’ Disease

Abstract

:Graves’ Disease

Literary Representations

One content, one sick in part;One warbling for the mere bright day’s delight,One longing for the night.(p. 10, ll. 212–14)

She cried “Laura,” up the garden,“Did you miss me?”Come and kiss me.…Eat me, drink me, love me;Laura, make much of me.”(p. 17, ll. 464–66, 471–72)

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Battiscombe, Georgina. 1981. Christina Rossetti: A Divided Life. London: Constable. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, Mackenzie. 1898. Christina Rossetti: A Biographical and Critical Study. London: Hurst and Blackett, Boston: Roberts Brothers. [Google Scholar]

- Blair, Kirstie. 2006. Victorian Poetry and the Culture of the Heart. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Briggs, Julia. 1999. Speaking Likenesses: Hearing the Lesson. In The Culture of Christina Rossetti: Female Poetics and Victorian Contexts. Edited by Mary Arseneau, Antony H. Harrison and Lorraine Janzen Kooistra. Athens: Ohio University Press, pp. 212–31. [Google Scholar]

- Broom, Brian. 2000. Medicine and story: A novel clinical panorama arising from a unitary mind/body approach to physical illness. Advances in Mind-Body Medicine 16: 161–207. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Broom, Brian. 2002. Somatic Metaphor: A Clinical Phenomenon Pointing to a New Model of Disease, Personhood, and Physical Reality. Advances in Mind-Body Medicine 18: 16–29. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rossetti, Christina. 1968. The Family Letters of Christina Rossetti. Edited by William Michael Rossetti. New York: Haskell. First published 1908. [Google Scholar]

- Rossetti, Christina. 1874. Annus Domini: A Prayer for Each Day of the Year, Founded on a Text of Holy Scripture. London: James Parker. [Google Scholar]

- Rossetti, Christina. 1892. The Face of the Deep: A Devotional Commentary on the Apocalypse. London: SPCK. [Google Scholar]

- Rossetti, Christina. 1994. “Vanna’s Twins.” 1870. In Christina Rossetti: Poems and Prose. Edited by Jan Marsh. London: J.M. Dent, pp. 314–23. [Google Scholar]

- Rossetti, Christina. 1997–2004. The Letters of Christina Rossetti. Edited by Antony H. Harrison. 4 vols. Charlottesville and London: University Press of Virginia. [Google Scholar]

- Rossetti, Christina. 1998. “Speaking Likenesses.” 1874. In Selected Prose of Christina Rossetti. Edited by David A. Kent and P. G. Stanwood. New York: St. Martin’s Press, pp. 117–51. [Google Scholar]

- Rossetti, Christina. 2001. Christina Rossetti: The Complete Poems. Text by R. W. Crump. Notes and Introduction by Betty S. Flowers. London: Penguin. [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell, Janis McLarren. 2004. Literature and Medicine in Nineteenth-Century Britain: From Mary Shelley to George Eliot. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Charon, Rita. 2006. Narrative Medicine: Honoring the Stories of Illness. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chiu, Wei-Yih, Chih-Chao Yang, I-Chueh Huang, and Tien-Shang Huang. 2004. Dysphagia as a Manifestation of Thyrotoxicosis: Report of Three Cases and Literature Review. Dysphagia 19: 120–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossetti, Dante Gabriel. 1967. Letters of Dante Gabriel Rossetti. Edited by Oswald Doughty and John Robert Wahl. Oxford: Clarendon Press, vol. 3. [Google Scholar]

- D’Amico, Diane. 2006. Christina Rossetti’s Breast Cancer: ‘Another Matter Painful to Dwell Upon’. The Journal of Pre-Raphaelite Studies 15: 28–50. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott and Fry, photogr. 1992. “Christina Rossetti.” Photograph. In Learning Not to Be First: The Life of Christina Rossetti. Edited by Kathleen Jones. New York: St. Martin’s Press, Fig. 19. [Google Scholar]

- Gosse, Edmund. 1903. Critical Kit-Kats. New York: Dodd, Mead and Company. [Google Scholar]

- Graves, Robert James. 1835. “Newly observed affection of the thyroid gland in females,” Clinical lectures delivered at the Meath Hospital during the session of 1834-5. Lecture XII. London Medical Surgical Journal 7: 516–17. [Google Scholar]

- Graves, Robert James. 1843. A System of Clinical Medicine. London: Longman. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, Antony H. 2007. Christina Rossetti: Illness and Ideology. Victorian Poetry 45: 415–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Esther T. 2010. Christina Rossetti and the Poetics of Tractarian Suffering. In Through a Glass Darkly: Suffering, the Sacred, and the Sublime in Literature and Theory. Edited by Holly Faith Nelson, Lynn R. Szabo and Jens Zimmermann. Waterloo: Wilfred Laurier University Press, pp. 155–67. [Google Scholar]

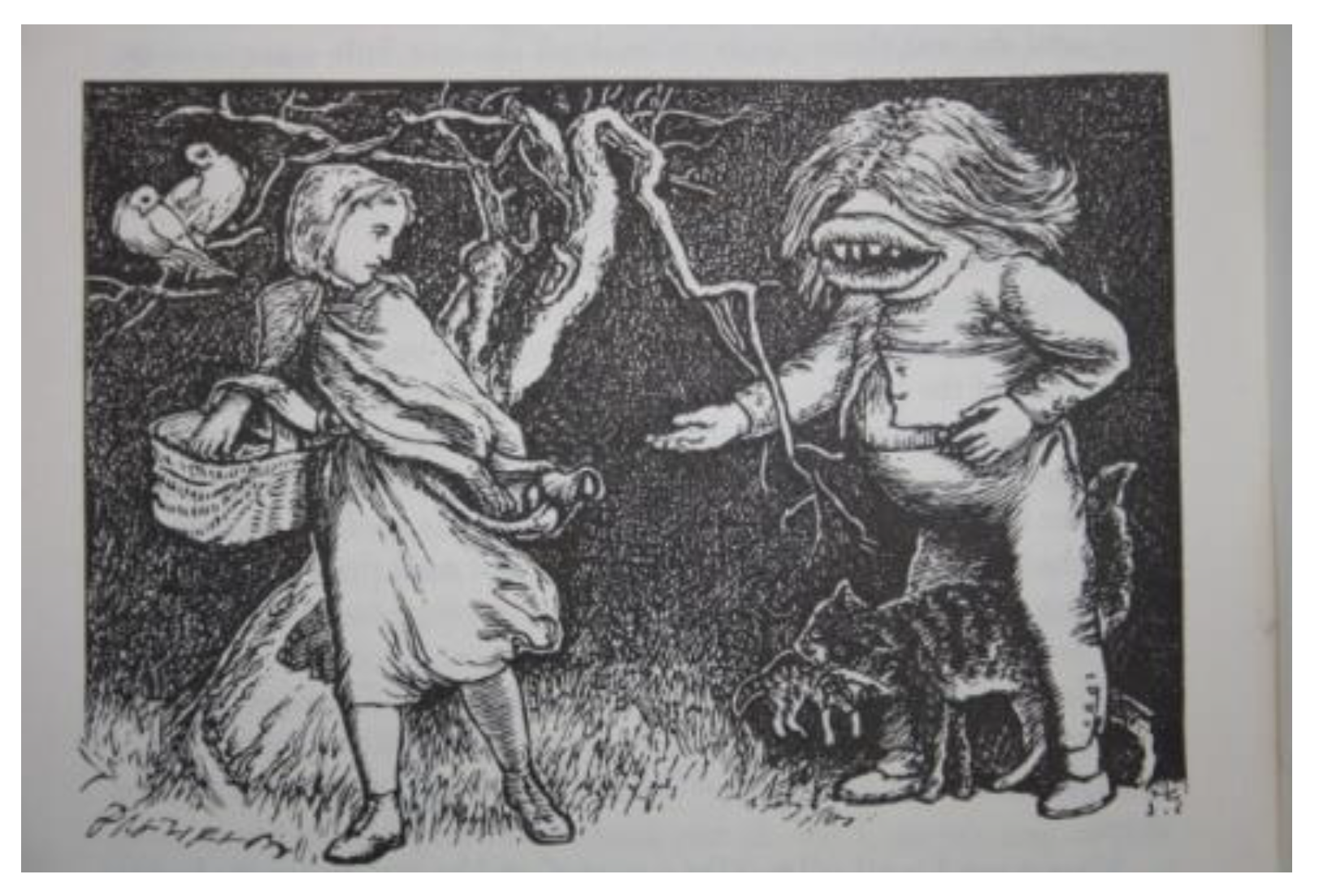

- Hughes, Arthur. 1998. The boy with the great mouth full of teeth grins at Maggie. Illustration for Christina Rossetti’s Speaking Likenesses. 1874. In Selected Prose of Christina Rossetti. Edited by David A. Kent and P. G. Stanwood. New York: St. Martin’s Press, p. 148. [Google Scholar]

- Humphries, Simon. 2017. Christina Rossetti’s ‘Religious Mania’. Notes and Queries 64: 116–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, Yusuf S., Jessica C. Hookham, Amit Allahabadia, and Sapabathy P. Balasubramanian. 2017. Epidemiology, management and outcomes of Graves’ disease-real life data. Endocrine 56: 568–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ives, Maura. 2011. Christina Rossetti: A Descriptive Bibliography. New Castle: Oak Knoll Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kent, David A. 1996. Christina Rossetti’s Dying. The Journal of Pre-Raphaelite Studies 5: 83–97. [Google Scholar]

- Kohl, James A. 1968. A Medical Comment on Christina Rossetti. Notes and Queries 15: 423–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawlor, Clark. 2006. Consumption and Literature: The Making of the Romantic Disease. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Leung, Angela M., and Lewis E. Braverman. 2014. Consequences of excess iodine. Nature Reviews Endocrinology 10: 136–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marsh, Jan. 1994. Christina Rossetti: A Literary Biography. London: Jonathan Cape. [Google Scholar]

- McIver, Bryan, and John C. Morris. 1998. The Pathogenesis of Graves’ Disease. Endocrinology and metabolism clinics of North America 27: 73–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medvei, Victor Cornelius. 1993. The History of Clinical Endocrinology: A Comprehensive Account of Endocrinology from Earliest Times to the Present Day, rev. ed. New York: Parthenon. [Google Scholar]

- Packer, Lona Mosk. 1963. Christina Rossetti. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds, J. Russell. 1890. A Contribution to the Clinical History of Graves’ Disease (Exophthalmic Goitre). The Lancet 135: 1055–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, Johanna. 2011. Illness narratives: Reliability, authenticity and the empathic witness. Medical Humanities 37: 68–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shorter, Edward. 1992. From Paralysis to Fatigue: A History of Psychosomatic Illness in the Modern Era. New York: Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sontag, Susan. 1978. Illness as Metaphor. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. [Google Scholar]

- Stokes, William. 1855. The Diseases of the Heart and the Aorta. Philadelphia: Lindsay and Blakiston. [Google Scholar]

- Volpé, Robert, and Clark Sawin. 2000. Graves’ Disease—A Historical Perspective. In Graves’ Disease: Pathogenesis and Treatment. Edited by Basil Rapoport and Sandra M. McLachlan. New York: Springer, pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Rossetti, William Michael, ed. 1900. The Poetical Works of Christina Georgina Rossetti. London: Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Rossetti, William Michael. 1977. The Diary of W.M. Rossetti. Edited by Odette Bornand. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Waldman, Suzanne B. 2009. The Demon and the Damozel: Dynamics of Desire in the Works of Christina Rossetti and Dante Gabriel Rossetti. Athens: Ohio University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Weathers, Winston. 1965. Christina Rossetti: The Sisterhood of Self. Victorian Poetry 3: 81–89. [Google Scholar]

- Weetman, A. P. 2003. Graves’ Disease 1835–2002. Hormone Research 59: 114–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| 1 | The intertwining of the fictional Maude’s failing health and Rossetti’s own is supported by an extant copy of Rossetti’s Verses (1847), inscribed and presented to her physician Charles Hare (Ives 2011, p. 32). In this presentation copy, Rossetti copies out a more recent composition, “Looking Forward.” This poem, in which the lyric speaker looks forward to death as a release from care and pain, biographically emerged from Rossetti’s own poor health, having been written in a period when Rossetti was too ill to even transcribe her own composition (W.M. Rossetti 1900, p. 478); it is included in the semi-autobiographical Maude as one of the last compositions of the dying poetess. |

| 2 | In this article D’Amico deliberately foregrounds Rossetti’s terminal illness, asking “What did it mean for a Victorian middle-class woman to die of breast cancer in 1894?” (D’Amico 2006, p. 30). Meanwhile, in her essay “Christina Rossetti and the Poetics of Tractarian Suffering”, Esther T. Hu considers closely Verses (1893), the volume that Rossetti assembled in her final illness, examining poems dealing with themes of pain, suffering, and grief, and emphasizing how they align with Tractarian theology that valued suffering as a means of spiritual improvement (Hu 2010, pp. 155–56). |

| 3 | Rossetti’s various biographers have offered much detailed information about Rossetti’s health and often relate illness to Rossetti’s poetic preoccupation with early death. Meanwhile, other critics have focused on biographical facts surrounding a particular illness (Kohl 1968; Humphries 2017; and D’Amico 2006) and the cultural contexts that influenced Rossetti’s illness experiences (Harrison 2007; Hu 2010; Blair 2006; and Kent 1996). |

| 4 | Rossetti biographers and critics have noted that Rossetti’s treating physician, Dr. Charles Hare, was still alive when Mackenzie Bell was writing the first full biography of Christina Rossetti, and he “gave his statement at first hand” to Bell. Hare reportedly said that the adolescent Rossetti was at that time “more or less out of her mind (suffering, in fact, from a form of insanity, I believe, a kind of religious mania)”. It was decided that this fact would be omitted from Bell’s biography “for obvious reasons […], tho’ the doctor’s good faith was not impugned” (Kohl 1968, pp. 423–24). However, the accuracy of this report has recently come under question. In a recent brief article, Simon Humphries for the first time brings into the biographical record Dr. Hare’s memoranda sent to Bell on 2 November 1896. Humphries probes the evidence, exposes misattributions, and very usefully corrects and clarifies this attribution to Dr. Hare of a diagnosis that the adolescent Rossetti suffered from “religious mania” (Humphries 2017). |

| 5 | For a discussion of the culturally constructed meaning attached to tuberculosis, see Susan Sontag’s Illness as Metaphor (Sontag 1978). |

| 6 | Marsh also suggests that the persistent cough may have been a tussis nervosa, a psychosomatic symptom. |

| 7 | Harrison speculates that Rossetti’s depression was the product of mid-Victorian ideology and rigid suppression of sexual desire (Harrison 2007, p. 422). |

| 8 | Many authoritative lists of Graves’ disease symptoms do not include difficulty swallowing or a choking sensation, but recent research reports that dysphagia is a rare manifestation of Graves’ disease (Chiu et al. 2004). The relationship of nervous symptoms to Graves’ disease has been debated. During the 1890s, doctors saw the nervous derangement as part of Graves’ disease and considered a whole range of “nervous disturbances” and “hysterical symptoms” as part of the disease presentation (Reynolds 1890, p. 1056). The authors are grateful to Diane D’Amico and Bonnie Cross for generously sharing their research on the history of Graves’ disease. |

| 9 | Stress is one of the environmental factors that can precipitate onset of Graves’ disease in a genetically predisposed individual. Toxins (including cigarette smoking), infections, hormones, and ageing are other factors that can play a role. Both infection and stress could have contributed in the case of Rossetti’s Graves’ disease. |

| 10 | The authors would like to thank Marjorie Stone (Dalhousie University) for bringing Broom’s work to our attention and for many inspiring and productive conversations on literature and medicine. |

| 11 | Although the Rossetti family record characterizes Graves’ disease as “rare,” it is the most common type of hyperthyroidism, with an incidence of 22–25 per 100,000 people in the United Kingdom. The female to male ratio is 3.9 to 1 (Hussain et al. 2017). The Rossetti family referred to the condition as both “Dr. Graves’s disease” and as “exophthalmic bronchocele”. Other names used today include “Basedow’s disease”, “autoimmune thyrotoxicosis”, “autoimmune hyperthyroidism”, and “toxic diffuse goiter”. |

| 12 | Graves’ description was first presented in clinical lectures delivered at the Meath Hospital during the session of 1834–35 and was published under the title “Newly observed affection of the thyroid gland in females” in the London Medical Surgical Journal (Graves 1835) and later republished in 1843 in Graves’ influential book A System of Clinical Medicine (1843). For the history of Graves’ disease, see Volpé and Sawin (2000), Weetman (2003), and Medvei (1993). |

| 13 | Stokes also notes that this condition occurs most often in females, and he associates the disease with a sensitive and nervous temperament and with “hysteria, neuralgia, or uterine disturbance” (Stokes 1855, p. 312). |

| 14 | This vague reference to “internal complaint” could refer to gastrointestinal hypermotility resulting in diarrheal-like stool or possibly to alterations in Rossetti’s menstrual cycle, both of which can occur with Graves’ disease. Such uncertainties highlight one of the limitations of the substantial written record—a sense of privacy and decorum that would have prevented Christina and others from describing some symptoms in detail. |

| 15 | Through this period, Rossetti continued to suffer from other sundry problems, a bad tooth, ear-aches, an abscess in her mouth that made her face swell, a cold, a hacking cough, and styes. |

| 16 | Today, thyroid storm, atrial fibrillation, and myocardial infarction would be considered serious risks. |

| 17 | Sir William Jenner had been known to Christina since 1854, but there is no record of Jenner attending her professionally until the 1860s; he continued treating her until his retirement in 1890 (Marsh 1994, p. 375). |

| 18 | “Dr. Fox,” William Michael wrote in his diary, “has seen only two cases of it (one of which he treated successfully), and Sir W. Jenner, as I understand, had also only seen two cases” (W.M. Rossetti 1977, p. 130). |

| 19 | Thomas Spencer Wells was surgeon to Queen Victoria’s household 1863–1896 (W.M. Rossetti 1977, p. 69 n3). |

| 20 | This is known as the Wolff–Chaikoff effect, whereby large doses of iodine will temporarily inhibit production of thyroid hormone. This effect is still taken advantage of today in the ICU setting for patients in a clinical thyroid storm. See Leung and Braverman (2014). |

| 21 | Digitalis is a medication that is still in use today, in the form of digoxin, for the symptomatic management of low ejection heart failure and atrial fibrillation. In Graves’ disease, it is possible to develop both of these states as a direct result of the hyperthyroid state. Digoxin can improve contractility and left ventricular ejection fraction, decrease sympathetic tone, and increase vagal tone. |

| 22 | William Michael records, “Maria was talking the other day to her surgical friend Mr Curgenvan about Christina’s illness. He says that he quite understands what it is, from the various statements he has heard about it. It is the malady called Dr. Graves’s disease, or exophthalmic bronchocele—very rare. A Dr. Cheadle has treated some cases successfully. The disease is (as we had been previously told) in the circulation of the blood: some congestion hence arising causes the swelling at the throat” (W.M. Rossetti 1977, p. 144). |

| 23 | Graves’ disease is an autoimmune thyroid disease which is characterized by hyperthyroidism and the production of autoantibodies which bind to and activate the thyrotropin receptor (TRAb). As these antibodies wrongfully overstimulate the thyroid gland, the synthesis of thyroid hormone becomes autologous, causing systemic disease. See McIver and Morris (1998). |

| 24 | In 1886, Paul Julius Moebious first proposed that hypersecretion from the thyroid gland could cause the disorder (Weetman 2003, p. 115). |

| 25 | Rossetti sent the manuscript to her publisher Alexander Macmillan on 4 February 1874 (C. Rossetti 1997–2004, vol. 2, p. 7). |

| 26 | Perhaps some lingering sensitivity on Rossetti’s part to her own altered appearance can be read in her description of Maggie’s thoughts on meeting the deformed boy: Maggie “tried not to stare, because she knew it would be rude to do so; though none the less amazed was she at his aspect” (C. Rossetti 1998, p. 147). |

| 27 | In “The Sisterhood of Self,” Winston Weathers uses Freudian psychoanalytic terms to discuss Rossetti’s lyric poetry as an allegorical sketch of “the fragmented self moving or struggling toward harmony and balance,” a theme which Weathers describes as “one of the major motifs in her mythic fabric” (Weathers 1965, p. 81). Georgina Battiscombe describes Rossetti’s life as one of strain and suffering caused by continual internal conflict between two sides of Rossetti’s personality, each side determined by one of two contesting cultural influences, English and Italian (Battiscombe 1981, pp. 13–14). More recently, Suzanne Waldman has described self-division as a key structure in Rossetti’s poems. Following Lacan, Waldman sees this split as a cleavage, not between the unconscious and the conscious, but between the imaginary and symbolic orders; for Christina, this duality is a Christian conflict within which the subject aspires to heaven while clinging to the world (Waldman 2009, p. 1). Marsh, meanwhile, observes that self-loathing is a recurrent theme in Rossetti’s poetry, noting that “the sense of a ‘dark double’ within her soul (‘traitor,’ ‘deadliest foe’) lay close to the surface of Christina’s personality” (Marsh 1994, p. 307). |

| 28 | Ague is a medical term indicating a febrile state involving alternating periods of fever, sweating, chills, and shivering. |

| 29 | “‘If thou sayest, behold, we knew it not,’” “The Thread of Life,” and “An Old World Thicket” (C. Rossetti 2001, pp. 329–36). |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Arseneau, M.; Terrell, E. “Our Self-Undoing”: Christina Rossetti’s Literary and Somatic Expressions of Graves’ Disease. Humanities 2019, 8, 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/h8010057

Arseneau M, Terrell E. “Our Self-Undoing”: Christina Rossetti’s Literary and Somatic Expressions of Graves’ Disease. Humanities. 2019; 8(1):57. https://doi.org/10.3390/h8010057

Chicago/Turabian StyleArseneau, Mary, and Emery Terrell. 2019. "“Our Self-Undoing”: Christina Rossetti’s Literary and Somatic Expressions of Graves’ Disease" Humanities 8, no. 1: 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/h8010057

APA StyleArseneau, M., & Terrell, E. (2019). “Our Self-Undoing”: Christina Rossetti’s Literary and Somatic Expressions of Graves’ Disease. Humanities, 8(1), 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/h8010057