Abstract

Victorian poet Christina Rossetti (1830–1894) was frequently troubled by poor health, and her mid-life episode of life-threatening illness (1870–1872) when she suffered from Graves’ disease provides an illuminating case study of the ways that illness can be reflected in poetry and prose. Rossetti, her family, and her doctors understood Graves’ disease as a heart condition; however, Rossetti’s writing reflects a different paradigm, presenting themes of self-attack and a divided self that uncannily parallel the modern understanding of Graves’ disease as autoimmune in nature. Interestingly, these creative representations reflect an understanding of this disease process that Rossetti family documents and the history of Victorian medicine demonstrate Rossetti could not have been aware of. When the crisis had passed, Rossetti’s writing began to include new rhetoric and imagery of self-acceptance and of suffering as a means of spiritual improvement. This essay explores the parallels between literary and somatic metaphors: Rossetti’s body and art are often simultaneously “saying” the same thing, the physical symptoms expressing somatically the same dynamic that is expressed in metaphor and narrative in Rossetti’s creative writing. Such a well-documented case history raises questions about how writing may be shaped by paradigms of illness that are not accessible to the conscious mind.

In his biographical “Memoir” of his sister, William Michael Rossetti observed, “any one who did not understand that Christina was an almost constant and often a sadly-smitten invalid, seeing at times the countenance of Death very close to her own, would form an extremely incorrect notion of her corporeal, and thus in some sense her spiritual, condition” (W.M. Rossetti 1900, p. l [50]). Victorian poet Christina Rossetti (1830–1894) suffered from a variety of health problems: when she was an adolescent, her health broke down dramatically, though the diagnosis is not clear. She suffered in young adulthood from heart symptoms, her recurring respiratory problems raised fears of incipient tuberculosis, and some of her doctors believed that Rossetti also suffered from hysteria. She endured repeated bouts of depression. In her early forties, her life was seriously endangered by Graves’ disease (autoimmune hyperthyroidism), which she survived but which left her heart and general health permanently weakened. Her final illness was breast cancer; she underwent a mastectomy, but the cancer recurred within a year, and she died at the age of 64. Illness clearly played a significant role in Rossetti’s life, but little has yet been written about the ways in which illness may have influenced her writing. Apart from the brief but frequent references to her current health in her letters, Rossetti did not write directly and specifically on the subject of her illnesses—she never wrote a pathography or an autobiographical illness narrative—but at every stage of her career Rossetti’s writings are inflected by her illness experience.

Christina Rossetti’s illness experience presents a fascinating literary case study, for we know that the medical community at the time fundamentally misunderstood the major life-threatening pathology from which she suffered. Her episode of serious illness in 1870–1872 was certainly due to Graves’ disease, and William Michael Rossetti’s diary records both the progress of his sister’s illness and many of the doctors’ treatments for it. We also know that Rossetti’s doctors correctly identified the disease but that their medical understanding of it was inaccurate. Graves’ disease is recognizable in Rossetti’s symptoms of rapid and powerful heartbeat, enlarged thyroid gland, and exophthalmos (protrusion of the eyeball from the socket); but at the time of Rossetti’s illness, these signs were all medically attributed to a cardiac syndrome in which the increased action of the heart causes the enlarged neck and bulging eyes. Doctors did not yet understand the role of the thyroid gland in this condition or the disease’s origins in autoimmune activity. Meanwhile, as a writer of poetry, fiction, and devotional prose, Rossetti herself offered a surprising—and until now overlooked—perspective on her illness, for her writings intersect with her physical and emotional experience of illness in both expected and unexplained ways. There are multiple modes for telling a story of illness, and Rossetti’s case presents of number of these for our study: a physical record of symptoms; social constructions of the meanings of her various ailments; Victorian medical framing of her sickness; modern understanding of the actual disease processes; Rossetti’s own metanarrative interpretation of her illness experience as spiritual correction; and finally, an array of Rossetti’s writings in poetry and prose that shed light on her inner lived experience—creative writings that seem to reflect unconsciously and uncannily the autoimmune disease process that was unknown to Rossetti and her doctors.

Rossetti’s experience of ill health influenced her outlook and creative choices throughout her adulthood and writing career. Following her adolescent illness, neither she nor her family expected that she would live a normal lifespan, a circumstance that in part explains her poetic preoccupation with death and the afterlife. Rossetti’s early novella, Maude, completed when she was 19, is particularly revealing in its semi-autobiographical depiction of a young and sickly poetess.1 Meanwhile, Rossetti’s decisive mid-career shift toward devotional prose works seems directly attributable to her nearly fatal bout with Graves’ disease. Prior to this major illness, Rossetti had expressed the feeling that she was spent creatively; unexpectedly, the illness reinvigorated her career as Rossetti began to explore a new genre and find a new publisher, audience, and public voice. Even to the end, illness exerted an influence on her art: as Diane D’Amico points out, Rossetti’s poetry, her religion, and her final illness all intersect in the creation of her last work, Verses (1893) (D’Amico 2006, p. 39).2 Despite the important role that illness played in Rossetti’s life, critics have done little to investigate illness’s important and pervasive relationship to her writings at a thematic and symbolic level.3

The role of illness in Rossetti’s life is a topic that has vexed biographers, who invariably remark upon her often vague and indefinite symptoms and on the advantages that Rossetti gained by being ill. They note that Christina’s prolonged adolescent illness conveniently exempted her from the expectation that she, like her older sister Maria, would have to work as a governess, a benefit that Christina herself consciously appreciated: “I know I am rejoiced to feel that my health does really unfit me for miscellaneous governessing en permanence” (C. Rossetti 1997–2004, vol. 1, p. 102). It was illness that freed Rossetti from having to undertake regular paid work and allowed her to pursue a vocation as a poet. Moreover, two of her early diagnoses—heart disease and possible tuberculosis—had important culturally-constructed meaning: they were seen as indications of the sufferer’s sensitivity and creativity. Rossetti’s illnesses thus both freed her to be a writer and marked her as a writer.

Briefly, after a healthy childhood, at the age of fourteen Rossetti’s health suddenly became precarious. The symptoms gave serious concern but were difficult to diagnose. Various eminent physicians were consulted, including Sir Thomas Watson, Sir Charles Locock (the Queen’s gynecologist), Dr. Peter Mere Latham, also known as “Heart” Latham, an expert on “nervous disease of the heart” (Blair 2006, p. 37) and Dr. Charles Hare, under whose constant care Rossetti remained from 1845 to 1850. This adolescent breakdown of bodily health appears to have been accompanied by a “severe nervous breakdown” (Marsh 1994, p. 51). Details of Rossetti’s mental state at this time were reportedly given in an interview between Dr. Hare and Rossetti’s biographer Mackenzie Bell, but Bell decided to suppress these details. Hare’s memoranda written to Bell in 1896 have recently been brought to light by Simon Humphries, and Hare’s notes describe a 15-year-old female of “a highly neurotic disposition & character” who presents a complex array of psychological and physiological symptoms.4 William Michael Rossetti would later recall that toward 1852, the diagnosis that had emerged was angina pectoris, which is severe chest pain caused by insufficient blood and oxygen supply to the heart muscle. Although this diagnosis was later questioned, Rossetti came to maturity under the belief that she suffered from a heart condition. As Kirstie Blair explains in Victorian Poetry and the Culture of the Heart, in this mid-century high-Victorian cultural milieu, Rossetti’s supposed heart condition would be read as an indication of her exquisite emotional sensitivity, her intense spirituality, and her poetic vocation (Blair 2006, pp. 1–22).

Rossetti also suffered from recurring pulmonary symptoms—persistent cough, bronchitis, lung congestion—which were alarmingly suggestive of consumption (or tuberculosis), a terrible disease that nonetheless was idealized in the 19th century as a disease of excessive passion and sensitivity. This diagnosis would have placed Rossetti in the company of poets such as John Keats, who suffered from what Clark Lawlor describes in Consumption and Literature as a glamorous Romantic disease and “a sign of passion, spirituality and genius”5 (Lawlor 2006, p. 2). Rossetti was prone to respiratory ailments, and doctors monitored her lungs carefully for decades. On doctor’s orders, she was often removed from the polluted air of London to spend periods of time at seaside destinations such as Hastings and Folkestone. For example, suffering from wracking headaches and an alarming cough that brought up blood, Rossetti spent the winter of 1864–1865 at Hastings. However, biographer Jan Marsh observes that in spite of her distressing symptoms, Rossetti was not suffering from tuberculosis or pneumonia6 (Marsh 1994, p. 318). Meanwhile, another Rossetti biographer, Lona Mosk Packer, observes that Rossetti was predisposed to pulmonary ailments, but that “it was chiefly during periods of emotional stress that latent susceptibilities burgeoned into symptoms” (Packer 1963, p. 244).

The intertwining of emotional and physical health that is evident throughout Rossetti’s life merits further attention. Marsh observes that “many of her bouts of illness seem to have been accompanied if not caused by depression, rendering her sufficiently listless for doctors to be called and sickness diagnosed” (Marsh 1994, pp. 168–69). Packer comments that throughout Rossetti’s life “emotional disturbances were paralleled by poor health” (Packer 1963, p. 190). Rossetti’s suffering was certainly due not only to physical causes but to psychological ones as well. Antony H. Harrison (editor of Rossetti’s letters) emphasizes that Rossetti “was a victim of chronic and sometimes severe depression”, something she herself acknowledged (Harrison 2007, p. 419).7 But in addition to the presentation of clinical depression, it seems likely that Rossetti’s psychological distress at times presented as physical symptoms.

Somatization (which Rossetti’s doctors referred to by the typically Victorian and more misogynistic term “hysteria”) also played a role in some of Rossetti’s symptoms. Somatization is an unconscious process by which psychological distress is converted to physical symptoms; a tension headache is a common example. Psychogenesis or somatization is a basic human response, writes Edward Shorter in his history of psychosomatic illness, and to suggest that a symptom is psychogenic (originating in the mind) in no way diminishes its reality and impact for the patient (Shorter 1992, p. x). To put this into context, Rossetti had numerous serious health problems that were unquestionably due to infection, physical disorder, or disease: these included anemia, lung congestion, bronchitis, abscesses, Graves’ disease, heart attacks, hypothyroidism, and cancer. But in addition to these, throughout her life Rossetti did present symptoms that are typical of hysteria or somatization, including fatigue, palpitations, choking sensations, dizziness, pain, headaches, and sore throat. For example, when Rossetti faints upon seeing her former fiancé, James Collinson, she is presenting a psychological event as a physical symptom. Ascertaining today the cause of Rossetti’s various symptoms is an unrealistic expectation, for the symptoms listed above that are usually attributed to hysteria can also have other causes. Graves’ disease itself causes nausea, loss of appetite, palpitations, dizziness, syncope, fatigue, and shortness of breath; furthermore, one of the treatments that Rossetti’s doctors prescribed for her condition, digitalis, also is known to cause these symptoms as side effects.

Some of Rossetti’s diagnoses are doubtful, including the possibility of tuberculosis or an underlying heart condition. William Michael indicates that in hindsight Christina’s diagnosis of angina pectoris in early adulthood seems questionable (W.M. Rossetti 1900, p. l [50]). Rossetti’s symptoms, which likely included heart palpitations, constriction in the chest, feeling of suffocation, and shortness of breath may have been due to psychological causes. Even during her “terrible illness” (Bell 1898, p. 31), Rossetti’s doctors believed that in addition to the symptoms of Graves’ disease, Rossetti was also troubled by hysterical symptoms. For instance, William Michael’s diary, a daily record that offers the best information on the course of Christina’s illness, records that Christina’s “difficulty in swallowing” was one of “the most troublesome details” of her illness; but Rossetti’s attending physician Dr. Wilson Fox explicitly declared that this was caused by “spasmodic nervous action”. The “choking sensation in her throat,” reported Fox, arose “entirely from nervous contraction, and not from any internal lump” (W.M. Rossetti 1977, pp. 123, 135–36). William Michael’s diary records a choking fit that left Christina “at the moment and afterwards, more scared and upset than I think I ever before saw her at any moment of pain or distress”8. Later, and presumably similar, experiences are recorded by William Michael as “hysterical attack[s]” (W.M. Rossetti 1977, pp. 136, 235). During Rossetti’s terminal illness, her doctor told William Michael “more than once” that Christina was “extremely subject” to hysteria (C. Rossetti [1908] 1968, p. 219). These diagnoses of hysteria came from highly respected and respectful doctors who were well aware of Rossetti’s organic illnesses, but who nevertheless identified an overlay of symptoms that they attributed to nervous rather than organic causes.

All the evidence suggests that Rossetti’s experience of psychological health and physical health were deeply interdependent. It is likely that psychosocial stress was sometimes converted to physical symptoms and that stress also was a contributing factor in organic disease. Current medical research continues to probe ways in which stress can compromise the immune system, leaving the body more susceptible to disease and infection. The interconnections among stress, depression, and the immune system are recognized and continue to be explored. From adolescence onward, Rossetti’s illnesses often occupy a gray area in which physical disease and psychological suffering coincide and influence each other. Later in life, her physical illness would have directly affected her mood: her hypothyroid condition is a known cause of depression; Graves’ disease causes nervous symptoms including irritability, nervousness, agitation, erratic behavior, and emotional lability. Furthermore, it is medically understood that in a susceptible individual Graves’ disease can be triggered or worsened by emotional stress.9 We would like to explore the possibility that for Rossetti this confluence of psychological and physical expression extends to a corresponding interdependence of mind and body in her artistic expression, demonstrated in previously unnoticed parallels between Rossetti’s illness and her imaginative writing, particularly as manifested in a striking similarity between the body’s expression of physical pathology (or what Brian Broom calls “somatic metaphor”) (Broom 2002, p. 16)10 and Rossetti’s creative expression (or literary metaphor). Of course, literature and medicine scholarship has frequently made careful study of artists’ creative expressions of their illness experience, but Rossetti’s writing and her experience of Graves’ disease make a particularly interesting case study because of the way that Rossetti’s literary metaphors seem to parallel the modern understanding of her affliction rather than the Victorian framing of her disease as her doctors explained it to her. If her literary metaphors reflect the physical process of her disease, they do so without Rossetti’s conscious awareness that they do so, for at this period in history these actual physical processes would have been unknown to her and her doctors.

Graves’ Disease

The life-threatening episode when Rossetti was in her early forties and was diagnosed with Graves’ disease had profound effects for her both physically and creatively, and it constitutes a hinge between two distinct portions of Rossetti’s career: upon recovering, Rossetti immediately composes Annus Domini: A Prayer for Each Day of the Year, Founded on a Text of Holy Scripture (published in April 1874; C. Rossetti 1874), the first of her six books of devotional prose, a new genre for her and one which would define the second half of her career. Written as a direct response to illness, Annus Domini deliberately frames physical suffering in spiritual terms. In presenting suffering through this religious lens, Rossetti does what many patients either consciously or unconsciously do in telling their illness narratives: she gives her own personal experience a narrative shape that conforms to an available and culturally-approved master narrative or meta-narrative (Shapiro 2011, p. 69), in this case a narrative of spiritual improvement. In Annus Domini, Rossetti asks Christ for the grace to see all suffering as heaven-sent: “sanctify and bless to us, I beseech Thee, all our sorrows and sufferings. In sickness, let Thy cross sustain us” (C. Rossetti 1874, p. 139). She prays for the grace to suffer patiently, and she asks for God’s healing: “O Lord Jesus Christ, Lord That healest us, have pity, I entreat Thee, on our bodies many ways afflicted; and bind up the wounds of our souls” (p. 10). What is clear is that the entire recent illness experience is framed as a sign of God’s love: “O Lord Jesus Christ, Who chastenest whom Thou lovest, grant us grace, I pray Thee, to discern Thy Love in whatever suffering Thou sendest us” (p. 292). Rossetti looks back on her illness as a correction sent by God; the physical suffering is divinely intended to effect spiritual transformation: “give each of us that good gift which Thou designest for us by Thy chastening. Before I was troubled I went wrong, but now will I keep Thy law. Amen” (p. 292). Rossetti writes of physical suffering as a stepping stone to an improved spiritual state, a paradigm that allows an artistic and spiritual trajectory out of the body. But Rossetti’s physical illness registered in her writing in other unrecognized ways as well, and understanding this correlation necessitates a fuller understanding of Rossetti’s experience and understanding of her illness.

Graves’ disease was recognized in Rossetti’s time by its hallmark triad of symptoms: a rapid, powerful heartbeat; goiter (enlargement of the thyroid gland); and exophthalmos (protrusion of the eyeball from the socket).11 Dr. Robert Graves identified these symptoms as constituting a single syndrome and made the disease widely known through his published description of it in the first half of the nineteenth century.12 In Graves’ description, the disease is framed as a cardiac syndrome in which the increased action of the heart is the cause of enlargement of first the thyroid gland and then the eyeballs. Graves emphasizes the heart’s violent “paroxysm of palpitation,” saying that in one patient “the beating of the heart could be heard during the paroxysm at some distance from the bed—a phenomenon I had never before witnessed, and which strongly excited my attention and curiosity” (Graves 1843, p. 674).

William Stokes’ later discussion (“Increased action of the heart and of the arteries of the neck, followed by enlargement of the thyroid gland and eye-balls”) published in The Diseases of the Heart and the Aorta in 1855 elaborates on Graves’ earlier description and more formally frames the disease as a cardiac syndrome, describing it as “a special form of cardiac neurosis.” Stokes emphasizes the nervous origins of the irregular heart function: “special nervous excitement” acting on the heart (Stokes 1855, pp. 298, 309). There is no organic disease of the heart when symptoms first appear, but the prolonged functional disturbance can lead to organic disease. Stokes thus describes the disease as primarily cardiac, though with an emphasis on hysterical and nervous influences.13

For Rossetti, the onset of symptoms was gradual, and for almost two years the doctors did not know their root cause. In May of 1870, Rossetti wrote to her friend Alice Boyd: “I do not know exactly what ‘the matter with me’ amounts to, but I am all out of sorts and lazy,” and some unidentified internal complaint begins to be felt (C. Rossetti 1997–2004, vol. 1, p. 354).14 On doctor’s orders, Rossetti spent much of the summer on an extended seaside recuperative holiday, but her symptoms continued: “my persistent weariness without exertion is something wonderful to contemplate,” Rossetti commented (C. Rossetti 1997–2004, vol. 1, p. 358). She continued in this uncertain state of health, but then in late April 1871 a serious crisis occurred. She became gravely ill, and on and off for the next two years her life was in jeopardy. Her symptoms at this point appear to have been fever, extreme weakness, complete loss of appetite, and an “enlarged throat” (C. Rossetti 1997–2004, vol. 1, p. 377). By late summer, the worst of the illness seemed to be over, but she was still weak, “completely altered” in appearance, “looking suddenly ten years older,” according to Dante Gabriel Rossetti (D.G. Rossetti 1967, vol. 3, p. 1022). But worse was yet to come: “enormous protrusion of the eyes” (W.M. Rossetti 1977, p. 232), faintness, rapid heartbeat, palpitations, difficulty swallowing, a choking sensation, severe headaches, extreme weakness and exhaustion, fainting, hair loss, frequent vomiting, weight loss, change in voice, continual shaking of her hands, skin discoloration, changed mental function, “a feeling of perpetual heat” (W.M. Rossetti 1977, p. 183), and eventually heart attacks.15 Death was common in Graves’ disease, and Rossetti’s doctors considered the chief danger to be exhaustion.16 By May of 1872, William Michael himself feared this outcome: “there seems to be no real rally of physical energy now for months past and the process of exhaustion proceeds with fatal and frightful steadiness” (W.M. Rossetti 1977, p. 198). But Rossetti did survive, and recovered to a good degree, though her heart and her appearance were permanently affected. At her worst, William Michael described her appearance as a “total wreck” (W.M. Rossetti 1977, p. 127), and all were very relieved to see her looks recover significantly. But the improvement was relative: in 1873, when critic and friend Edmund Gosse encountered the now-recovered Christina at the British Museum, he found her “so strangely altered as to be scarcely recognisable” (Gosse 1903, p. 159). Although no written record confirms this surmise, one of the permanent changes to Rossetti’s appearance might well have been asymmetrical eye alignment, visible in an 1877 photographic portrait that shows her left eye gazing directly at the camera, while the right eye is oriented off to the right (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Christina Rossetti, 1887, photograph by Elliott and Fry (1992).

Throughout this illness, Rossetti was under the meticulous care of Drs William Jenner and Wilson Fox17, leading physicians who also attended Queen Victoria, and by late 1871 they had correctly diagnosed Rossetti’s illness as Graves’ disease. Ineffectual though treatment was, Rossetti did receive the best medical care available. Both doctors had some experience with this “very rare” condition.18 From letters and William Michael’s diary we can glean a few details of her medical treatment. Surgery was considered (presumably removal of the thyroid gland), and Dr. Jenner brought in the distinguished surgeon Spencer Wells to examine Rossetti.19 Her “enlarged throat” was treated with iodine20; when her heart symptoms presented, digitalis was prescribed to regulate the heart.21 Dr. Fox’s plan was for “keeping up the system as much as possible by frequent glasses of wine.” Fox also prescribed “early tea with brandy” which Christina thought helped with her “frequent headaches of a very aggravated kind” (W.M. Rossetti 1977, pp. 126, 127). The main prescription was rest, sea air when she was well enough to travel, avoidance of the exertion of climbing stairs, and absolutely complete bed rest at the worst of the illness.

It was not until early January 1872 that the family first learned, through Maria Rossetti, the actual name of the malady, “Dr. Graves’s disease, or exophthalmic bronchocele” (W.M. Rossetti 1977, p. 144).22 But although Dr. Fox had not yet mentioned the name of the disease, his discussions with the family make clear that he had already identified the malady in November of the previous year. By this period Jean Martin Charcot and Armand Trousseau had proposed (incorrectly) that the disease was neurological in nature, but Jenner and Fox consistently describe Rossetti’s condition as disturbed action of the heart, the disease model described by Graves and Stokes. Fox called Rossetti’s heart symptoms “accelerated circulation” (W.M. Rossetti 1977, p. 127). William Michael records the details offered by Fox: “The thing that is essentially the matter with her now is connected with the heart […], though not amounting strictly to heart disease. The swelling outside the throat and other symptoms depend on this same malady” (W.M. Rossetti 1977, p. 130). Even more significantly, Christina’s own letters demonstrate that it was explicitly in these terms that she herself understood her condition. Late in 1873, during a period of emotional stress, Rossetti suffers what she describes as “a serious relapse into heart complaint & consequent throat enlargement” (C. Rossetti 1997–2004, vol. 1, p. 437). Rossetti understood herself to be suffering from a recurring heart complaint in which the disordered function of the heart causes the other visible symptoms (enlargement in throat and eyes).

Today, however, Graves’ disease is understood as an autoimmune thyroid disease.23 In simple terms, in an autoimmune disease the organism fails to recognize some part of the body as “self,” and the immune system begins to attack the body’s own cells or tissue. Self-tolerance is lost: self fails to recognize the self, and self attacks the self. Rossetti’s experience of Graves’ disease in the 1870s predates medical understanding of the thyroid gland’s role in the disease; indeed, the study of endocrinology did not yet exist.24 The category of diseases now known as “autoimmune” would not be hypothesized until the 20th century. Unquestionably, this modern framing of her disease was completely unknown to Rossetti, yet her writings mirror in surprising ways this autoimmune pathology. Rossetti repeatedly dramatizes and represents metaphorically the same self-attack that underlies the autoimmune dynamic, as a fragmented or divided self, a symbolic resonance and confluence that warrants further examination. The body’s expression in somatic metaphor appears in Rossetti’s case to mirror and to be mirrored in literary metaphors. Rossetti’s pathological self-attack at a cellular level and the imagery and themes explored in her poetry and prose mutually reflect and echo each other. After Rossetti survived her battle with Graves’ disease, these poetic expressions changed: internal divisions were now consciously rejected, and movement toward self-acceptance became a prominent theme. Of course, this is to suggest that Rossetti was creatively preoccupied with themes and metaphors that uncannily portray with a remarkable accuracy the disease to which she is predisposed, and that she did so without any conscious understanding of autoimmune disease, indeed long before the model of autoimmune disease had even been conceptualized.

Literary Representations

New understanding of Rossetti’s writing can emerge when her poetry and prose are read through the lens of this medical history. Two works of fiction resonate specifically in the context of her major health crisis with Graves’ disease: first, the short story “Vanna’s Twins” written in 1869–1870, within months of the first recorded symptoms of Graves’ disease, and second, Speaking Likenesses, written shortly after her illness.25 In both stories, Rossetti represents a divided self in potentially life-threatening circumstances. While not autobiographical, the earlier tale, “Vanna’s Twins,” reflects aspects of Rossetti’s own experiences, in the middle-aged spinster narrator who comes to the seaside town to recuperate from recent illness, and in the Italian family she lodges with and befriends (Vanna, her husband, and their twin children). Interestingly, the plot is consistently motivated by illness. On the fateful day, the twins’ father is away from home in order to collect an outstanding debt so that he in turn can pay the doctor’s bill owing since the twins’ recent treatment for scarlatina. In his absence, an impoverished young mother rushes into town frantically looking for the doctor for her three young ones who are “down with the fever” (C. Rossetti 1994, p. 320). The narrator resolves to make a charitable contribution to the poor family the next day; Vanna, however, acts independently and more immediately, sending her seven-year-old twins to deliver oranges to the sick children. The narrator, alert to the onset of a winter storm, is filled with misgiving. Meanwhile, the twins safely reach the sick children’s cottage and then contemplate their homeward journey. Significantly they have conflicting impulses at this point: the female, Gioconda, is tearful and wants to stay in the cottage and warm herself; her brother, Felice, is determined to keep his word to their mother and not loiter. They set out but do not reach home; days later they are found frozen to death locked in an embrace. In this story of twinned characters and competing impulses, harmonization is desired but denied, with tragic consequences. The twins’ unity is emphasized throughout the tale, they are “like one work in two volumes” (C. Rossetti 1994, p. 319) and their shared fate is determined by their only occasion of internal division. Just as in Graves’ disease, by which a misguided immune system dutifully performs a role which turns out to be self-destructive, Felice obediently insists on returning home as promised, and in doing so refuses to recognize the self and its needs—the healthy instinct for self-preservation expressed in Gioconda’s cries for warmth, rest, and shelter.

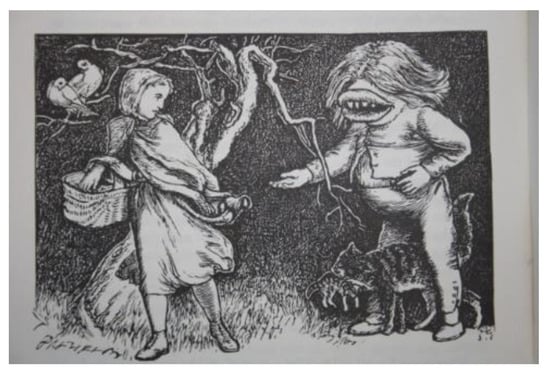

Within months of finishing this story, Rossetti acknowledges in writing her own poor state of health. Significantly, the only mention of “Vanna’s Twins” in Rossetti’s four volumes of collected letters is followed almost immediately by the first acknowledgement of her puzzling illness (C. Rossetti 1997–2004, vol. 1, p. 354). As already mentioned, Rossetti’s first project upon recovery is Annus Domini, her first book of devotional prose. In the same year, Rossetti also wrote and published Speaking Likenesses, three linked tales for children, in which she returns to the motif of a child sent on a potentially dangerous winter’s errand. As Rossetti explained to her publisher Alexander Macmillan, “my small heroines perpetually encounter ‘speaking (literally speaking) likenesses’ or embodiments or caricatures of themselves or their faults” (C. Rossetti 1997–2004, vol 2, p. 19). Through these “embodiments,” Julia Briggs suggests, Rossetti depicts a self doubled into self and anti-self (Briggs 1999, p. 215). In the final tale in Speaking Likenesses, young Maggie volunteers to deliver forgotten Christmas purchases to a doctor’s house on a cold Christmas Eve. On the way, she falls and hits her head, and then meets fantastical figures: children at play, a grotesque boy who demands the chocolate Maggie is delivering, and a group of mysterious sleepers. Briggs rightly suggests that these are projections of Maggie’s desire to play, eat, and rest (Briggs 1999, p. 218), but each of these fantastical beings also embodies aspects of Rossetti’s recent illness: the playing children are feverishly overheated and “you might have heard and seen their hearts beat” (C. Rossetti 1998, p. 145), the very clinical phenomenon that Graves described; the boy who tries to steal food has a face which is all mouth and no eyes, an inversion of Rossetti’s own loss of appetite and wildly prominent eyes (Figure 2, C. Rossetti 1998, p. 148)26; finally, the sleepers tempt Maggie to give in to potentially fatal exhaustion, for the narrator warns her listeners that to yield to sleep in such cold would mean death (C. Rossetti 1998, p. 149). Maggie resists these temptations and reaches the doctor’s home, where she hopes to be “asked indoors, warmed by a fire, […] and indulged with a glimpse of the Christmas tree”; however, she receives only a perfunctory “Thank you” before the door is shut on her (C. Rossetti 1998, p. 149). Not unlike Rossetti herself, Maggie gets no effective help from the doctor.

Figure 2.

“The boy with the great mouth full of teeth grins at Maggie” (Hughes 1998).

Disappointed, cold, tired, and hungry, Maggie begins her walk homeward and again has three encounters as she comes upon a dove, a kitten, and then a puppy. As Briggs observes, in these abandoned animals Maggie is encountering her needs in a second form, and, “in an act of vicarious nurture, she cares for herself by caring for them” (Briggs 1999, p. 218). At the precise sites where Maggie had first encountered dangerous and diseased projections of herself, she now meets embodiments that invite and allow her to recognize and care for herself. Motivated and reinvigorated by concern for the animals she has taken into her care, Maggie “ran along singing quite merrily under her burden” (C. Rossetti 1998, p. 150). Thus, while internal divisions mirroring Rossetti’s incipient disease led to tragedy in “Vanna’s Twins”, the recovered Rossetti now writes a second journey narrative in which metaphoric representations of her illness are overcome, and in which self-recognition and self-care ultimately lead her young heroine to home and safety.

If both are read symbolically, Rossetti’s illness and her fiction written at the same period are “saying” the same thing: literary and somatic metaphor reinforce and explicate each other. Interestingly, these parallels between Rossetti’s illness and her verbal expressions are not as singular as we might expect. Physician and psychotherapist Brian Broom has documented and catalogued the clinical phenomenon of what he calls “somatic metaphor,” instances where a physical disease seems to be expressing the same meaning as the patient’s subjective story expresses in verbal language. But Broom and many others go further in questioning the fundamental paradigm that sees mind and body as separate. Broom argues that disease presentation and verbal language are often confluent because they are both expressions of the same personhood, the combined mind/body and individual unity from which both story and symptom emerge (Broom 2000, p. 164). In this model, neither the body language nor verbal language are primary. As Broom points out, while the influence of psychosocial factors on body and disease is accepted, though not fully understood, there is no current medical model that would explain the often observed symbolic or metaphorical match between organic disease and life story which Broom documents and which is also discernible in Rossetti’s life and writing.

The resonance between what Rossetti’s illness is “saying” and what Rossetti is saying fictionally in “Vanna’s Twins” and Speaking Likenesses extends even further, for the representation of a self harmfully divided within and against itself is a key motif in Rossetti’s poetry as well. Works predating 1870 often express a (dis)ease with self and a fragmented self, a central theme that has been recognized since the earliest modern reappraisal of Rossetti.27 Furthermore, in Rossetti’s writing such states of internal conflict are often linked to illness (as the sickly, conflicted, self-critical fictional poetess in Maude exemplifies). Rossetti writes of the fragmented self as a source of sickness in various intensely personal poems arising out of periods of illness. For example, in the second section of “Three Stages” (an utterance so personal that she did not publish it in her lifetime), Rossetti writes of the self turning on the self in punitive destruction: “I must pull down my palace that I built,/Dig up the pleasure-gardens of my soul” (C. Rossetti 2001, p. 765, part 2, ll. 9–10). This self-attack leaves her fragmented and sick: “Part of my life is dead, part sick, and part / Is all on fire within” (C. Rossetti 2001, p. 765, 2:15–16). Meanwhile, in “Who Shall Deliver Me?” Rossetti contemplates this internal enemy, asking “who shall wall / Self from myself, most loathed of all?” (C. Rossetti 2001, p. 220, ll. 8–9), and she seeks protection from this life-threatening self, a “strangling load” (C. Rossetti 2001, p. 221, l. 23) and an “arch-traitor to myself;/My hollowest friend, my deadliest foe” (C. Rossetti 2001, p. 221, ll. 19–20).

Fragmentation is also potentially fatal in Rossetti’s most-studied poem, “Goblin Market.” The sisters Laura and Lizzie (closely identified and often read as two aspects of one psyche) exist in a state of health and harmony until Laura alone eats the forbidden goblin fruit. While Lizzie remains unchanged, “with an open heart” (C. Rossetti 2001, p. 10, l. 210), Laura is now “in an absent dream” (p. 10, l. 211). They are divided:

One content, one sick in part;One warbling for the mere bright day’s delight,One longing for the night.(p. 10, ll. 212–14)

Laura enters a life-threatening decline; determined to help her sister, Lizzie resolves to purchase goblin fruit for her. Following a violent encounter with the goblin men that leaves Lizzie dripping with goblin fruit pulp and juices, in the poem’s climactic passage Lizzie offers Laura the cure, in form of both an antidote and a healing reunion with her sister:

She cried “Laura,” up the garden,“Did you miss me?”Come and kiss me.…Eat me, drink me, love me;Laura, make much of me.”(p. 17, ll. 464–66, 471–72)

Clearly “Goblin Market” is a poem that is preoccupied with states and signs of illness and health, and we see how this poem reiterates Rossetti’s framing of health as a state of integration and self-division as a source of illness. Furthermore, this poem pays consistent attention to the physical body and its involuntary, unwilled symptoms and signs. For example, the goblins’ cries elicit from Lizzie “blushes” (p. 6, l. 35) and from both sisters “tingling cheeks and finger tips” (p. 6, l. 39), all of which are specific physical responses to stress (and sex, another essential physical aspect in interpretations of the poem). Rossetti describes this charged situation as registering on the body. In fact, the poem throughout attests to Rossetti’s attunement to bodily signs, from Laura’s salivation for more goblin fruit—“my mouth waters still” (p. 9, l. 166)—to the physical harm wrought by the ingested fruit: the dwindling (p. 12, l. 278), the thinning, graying hair (p. 12, l. 277), and the “sunk eyes and faded mouth” (p. 12, l. 288). Laura is “Thirsty, cankered” (p. 17, l. 484), and “Shaking with aguish fear, and pain”28 (p. 18, l. 491). Taking the bitter medicine, Laura’s “lips began to scorch” (p. 18, l. 492) and “Swift fire spread thro’ her veins” (p. 18, l. 507). The healing crisis is violent and intense; Laura is “Writhing as one possessed” (p. 18, l. 496) before she falls into a state of unconsciousness. Now, Lizzie actively nurses her sister, “Counted her pulse’s flagging stir,/Felt for her breath,/Held water to her lips, and cooled her face/With tears and fanning leaves” (p. 19, ll. 526–29). Finally, Laura’s restored health is documented in the physical signs: “Her gleaming locks showed not one thread of grey,/Her breath was sweet as May/And light danced in her eyes” (p. 19, ll. 540–42). In spite of the fact that “Goblin Market” has attracted an enormous amount of critical scrutiny in the past few decades, there has been no sustained attempt to read the poem’s many references to the body, health, and illness through the lens of Rossetti’s own experience of illness.

Rossetti’s experience of Graves’ disease was a pivotal point in her life and career. Following this illness, Rossetti’s representations of the self undergo a transformation. In three contiguous poems29 in her first poetic collection following her illness, A Pageant and Other Poems (1881), Rossetti acknowledges the dynamics of self-laceration, rejects such inward-turned destructiveness, and seeks healing for the wounds she herself has inflicted. In “An Old World Thicket,” the speaker begins her journey in a state of despair and internal strife which she vividly describes through imagery of violent self-attack: “Self stabbing self with keen lack-pity knife” (C. Rossetti 2001, p. 333, l. 45). In another poem, she prays for healing of her self-inflicted wounds, beseeching, “Lord undo/Our self-undoing” (C. Rossetti 2001, p. 329, ll. 7–8). Meanwhile, “The Thread of Life” explicitly articulates self-acceptance: “I am not what I have nor what I do;/But what I was I am, I am even I” (C. Rossetti 2001, p. 331, part 2, ll. 13–14). In her last work of devotional prose, The Face of the Deep, Rossetti elaborates theologically on the “inextinguishable I,” the immortal, immutable aspect of selfhood that is both inherited from and corresponds to the Divine (C. Rossetti 1892, p. 536). In Rossetti’s life story and artistic project this recognition and acceptance of herself has simultaneously been learned theologically, experienced physiologically, and expressed artistically: “I who am myself cannot but be myself. I am what God has constituted me […]. Who I was I am, who I am I am, who I am I must be for ever and ever […]. I may loath myself or be amazed at myself, but I cannot unself myself for ever and ever” (C. Rossetti 1892, p. 47).

In Narrative Medicine, Rita Charon asserts that “Illness occasions the telling of two tales of self at once, one told by the “person” of the self and the other told by the body of the self” (Charon 2006, p. 87). Respect for these two modes of telling would have been modeled by Rossetti’s own doctors. Janis McLarren Caldwell asserts that “the most important development of nineteenth-century British medicine was the ‘history and physical’ format for diagnosing illness” (Caldwell 2004, p. 8), a format that encompasses both patient’s subjective narration and the physician’s objective findings in physical examination. Such a method, observes Caldwell, invites a “dialectical hermeneutic,” an interpretive technique that oscillates between the “physical evidence and inner, imaginative understanding” (Caldwell 2004, p. 1). By the early 1840s medical students were being trained in this “history and physical” format. Dr. Hare, Rossetti’s physician during her first extended illness, wrote prize-winning case reports—long, detailed documents with the history mainly recorded in the patient’s own words (Caldwell 2004, pp. 150–51). Attended by Dr. Hare between the ages of 15 and 20 years, Rossetti would have learned that patient narrative or “story” is worthy of careful attention, that both the patient’s story and the physical signs are equally important expressions of illness.

Given that both the Victorian and the current medical framings of Graves’ disease acknowledge the role that stress can play in the onset or worsening of this disease, it is completely compatible with medical understanding to consider Rossetti’s life story and psychological state as meaningful in relation to this illness. Today, an emotional and psychological state of self-laceration would itself be recognized as the kind of stress that could lead to autoimmune disease expression in a pre-disposed individual; but the expressive correlation between literary metaphor and physiological processes that is exemplified in Rossetti’s life and writing is remarkable and deserving of further study, for this is less explicable in terms of current mind/body models. It is accepted that stories are shaped by a variety of forces, and images and metaphors can emerge from sources other than those under the control of deliberate and conscious thought. We currently recognize that the unconscious mind can be an important source of artistic creativity: Is it possible that the body’s unconscious physical operations might also be a source of metaphor in a creative individual? This complex topic is genuinely interdisciplinary, raising questions in fields ranging from medicine and cognitive psychology to philosophy, language theory, literary criticism, and aesthetics as we seek to better understand ways of communicating illness.

Author Contributions

The co-authors collaborated on this article. M.A.’s contributions focused on Christina Rossetti and her writings, while E.T.’s contributions focused on the medical aspects of the essay.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the scholarly generosity of Marjorie Stone (Dalhousie University), Diane D’Amico and Bonnie Cross (Allegheny College).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Battiscombe, Georgina. 1981. Christina Rossetti: A Divided Life. London: Constable. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, Mackenzie. 1898. Christina Rossetti: A Biographical and Critical Study. London: Hurst and Blackett, Boston: Roberts Brothers. [Google Scholar]

- Blair, Kirstie. 2006. Victorian Poetry and the Culture of the Heart. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Briggs, Julia. 1999. Speaking Likenesses: Hearing the Lesson. In The Culture of Christina Rossetti: Female Poetics and Victorian Contexts. Edited by Mary Arseneau, Antony H. Harrison and Lorraine Janzen Kooistra. Athens: Ohio University Press, pp. 212–31. [Google Scholar]

- Broom, Brian. 2000. Medicine and story: A novel clinical panorama arising from a unitary mind/body approach to physical illness. Advances in Mind-Body Medicine 16: 161–207. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Broom, Brian. 2002. Somatic Metaphor: A Clinical Phenomenon Pointing to a New Model of Disease, Personhood, and Physical Reality. Advances in Mind-Body Medicine 18: 16–29. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rossetti, Christina. 1968. The Family Letters of Christina Rossetti. Edited by William Michael Rossetti. New York: Haskell. First published 1908. [Google Scholar]

- Rossetti, Christina. 1874. Annus Domini: A Prayer for Each Day of the Year, Founded on a Text of Holy Scripture. London: James Parker. [Google Scholar]

- Rossetti, Christina. 1892. The Face of the Deep: A Devotional Commentary on the Apocalypse. London: SPCK. [Google Scholar]

- Rossetti, Christina. 1994. “Vanna’s Twins.” 1870. In Christina Rossetti: Poems and Prose. Edited by Jan Marsh. London: J.M. Dent, pp. 314–23. [Google Scholar]

- Rossetti, Christina. 1997–2004. The Letters of Christina Rossetti. Edited by Antony H. Harrison. 4 vols. Charlottesville and London: University Press of Virginia. [Google Scholar]

- Rossetti, Christina. 1998. “Speaking Likenesses.” 1874. In Selected Prose of Christina Rossetti. Edited by David A. Kent and P. G. Stanwood. New York: St. Martin’s Press, pp. 117–51. [Google Scholar]

- Rossetti, Christina. 2001. Christina Rossetti: The Complete Poems. Text by R. W. Crump. Notes and Introduction by Betty S. Flowers. London: Penguin. [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell, Janis McLarren. 2004. Literature and Medicine in Nineteenth-Century Britain: From Mary Shelley to George Eliot. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Charon, Rita. 2006. Narrative Medicine: Honoring the Stories of Illness. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chiu, Wei-Yih, Chih-Chao Yang, I-Chueh Huang, and Tien-Shang Huang. 2004. Dysphagia as a Manifestation of Thyrotoxicosis: Report of Three Cases and Literature Review. Dysphagia 19: 120–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossetti, Dante Gabriel. 1967. Letters of Dante Gabriel Rossetti. Edited by Oswald Doughty and John Robert Wahl. Oxford: Clarendon Press, vol. 3. [Google Scholar]

- D’Amico, Diane. 2006. Christina Rossetti’s Breast Cancer: ‘Another Matter Painful to Dwell Upon’. The Journal of Pre-Raphaelite Studies 15: 28–50. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott and Fry, photogr. 1992. “Christina Rossetti.” Photograph. In Learning Not to Be First: The Life of Christina Rossetti. Edited by Kathleen Jones. New York: St. Martin’s Press, Fig. 19. [Google Scholar]

- Gosse, Edmund. 1903. Critical Kit-Kats. New York: Dodd, Mead and Company. [Google Scholar]

- Graves, Robert James. 1835. “Newly observed affection of the thyroid gland in females,” Clinical lectures delivered at the Meath Hospital during the session of 1834-5. Lecture XII. London Medical Surgical Journal 7: 516–17. [Google Scholar]

- Graves, Robert James. 1843. A System of Clinical Medicine. London: Longman. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, Antony H. 2007. Christina Rossetti: Illness and Ideology. Victorian Poetry 45: 415–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Esther T. 2010. Christina Rossetti and the Poetics of Tractarian Suffering. In Through a Glass Darkly: Suffering, the Sacred, and the Sublime in Literature and Theory. Edited by Holly Faith Nelson, Lynn R. Szabo and Jens Zimmermann. Waterloo: Wilfred Laurier University Press, pp. 155–67. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, Arthur. 1998. The boy with the great mouth full of teeth grins at Maggie. Illustration for Christina Rossetti’s Speaking Likenesses. 1874. In Selected Prose of Christina Rossetti. Edited by David A. Kent and P. G. Stanwood. New York: St. Martin’s Press, p. 148. [Google Scholar]

- Humphries, Simon. 2017. Christina Rossetti’s ‘Religious Mania’. Notes and Queries 64: 116–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, Yusuf S., Jessica C. Hookham, Amit Allahabadia, and Sapabathy P. Balasubramanian. 2017. Epidemiology, management and outcomes of Graves’ disease-real life data. Endocrine 56: 568–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ives, Maura. 2011. Christina Rossetti: A Descriptive Bibliography. New Castle: Oak Knoll Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kent, David A. 1996. Christina Rossetti’s Dying. The Journal of Pre-Raphaelite Studies 5: 83–97. [Google Scholar]

- Kohl, James A. 1968. A Medical Comment on Christina Rossetti. Notes and Queries 15: 423–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawlor, Clark. 2006. Consumption and Literature: The Making of the Romantic Disease. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Leung, Angela M., and Lewis E. Braverman. 2014. Consequences of excess iodine. Nature Reviews Endocrinology 10: 136–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marsh, Jan. 1994. Christina Rossetti: A Literary Biography. London: Jonathan Cape. [Google Scholar]

- McIver, Bryan, and John C. Morris. 1998. The Pathogenesis of Graves’ Disease. Endocrinology and metabolism clinics of North America 27: 73–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medvei, Victor Cornelius. 1993. The History of Clinical Endocrinology: A Comprehensive Account of Endocrinology from Earliest Times to the Present Day, rev. ed. New York: Parthenon. [Google Scholar]

- Packer, Lona Mosk. 1963. Christina Rossetti. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds, J. Russell. 1890. A Contribution to the Clinical History of Graves’ Disease (Exophthalmic Goitre). The Lancet 135: 1055–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, Johanna. 2011. Illness narratives: Reliability, authenticity and the empathic witness. Medical Humanities 37: 68–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shorter, Edward. 1992. From Paralysis to Fatigue: A History of Psychosomatic Illness in the Modern Era. New York: Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sontag, Susan. 1978. Illness as Metaphor. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. [Google Scholar]

- Stokes, William. 1855. The Diseases of the Heart and the Aorta. Philadelphia: Lindsay and Blakiston. [Google Scholar]

- Volpé, Robert, and Clark Sawin. 2000. Graves’ Disease—A Historical Perspective. In Graves’ Disease: Pathogenesis and Treatment. Edited by Basil Rapoport and Sandra M. McLachlan. New York: Springer, pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Rossetti, William Michael, ed. 1900. The Poetical Works of Christina Georgina Rossetti. London: Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Rossetti, William Michael. 1977. The Diary of W.M. Rossetti. Edited by Odette Bornand. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Waldman, Suzanne B. 2009. The Demon and the Damozel: Dynamics of Desire in the Works of Christina Rossetti and Dante Gabriel Rossetti. Athens: Ohio University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Weathers, Winston. 1965. Christina Rossetti: The Sisterhood of Self. Victorian Poetry 3: 81–89. [Google Scholar]

- Weetman, A. P. 2003. Graves’ Disease 1835–2002. Hormone Research 59: 114–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| 1 | The intertwining of the fictional Maude’s failing health and Rossetti’s own is supported by an extant copy of Rossetti’s Verses (1847), inscribed and presented to her physician Charles Hare (Ives 2011, p. 32). In this presentation copy, Rossetti copies out a more recent composition, “Looking Forward.” This poem, in which the lyric speaker looks forward to death as a release from care and pain, biographically emerged from Rossetti’s own poor health, having been written in a period when Rossetti was too ill to even transcribe her own composition (W.M. Rossetti 1900, p. 478); it is included in the semi-autobiographical Maude as one of the last compositions of the dying poetess. |

| 2 | In this article D’Amico deliberately foregrounds Rossetti’s terminal illness, asking “What did it mean for a Victorian middle-class woman to die of breast cancer in 1894?” (D’Amico 2006, p. 30). Meanwhile, in her essay “Christina Rossetti and the Poetics of Tractarian Suffering”, Esther T. Hu considers closely Verses (1893), the volume that Rossetti assembled in her final illness, examining poems dealing with themes of pain, suffering, and grief, and emphasizing how they align with Tractarian theology that valued suffering as a means of spiritual improvement (Hu 2010, pp. 155–56). |

| 3 | Rossetti’s various biographers have offered much detailed information about Rossetti’s health and often relate illness to Rossetti’s poetic preoccupation with early death. Meanwhile, other critics have focused on biographical facts surrounding a particular illness (Kohl 1968; Humphries 2017; and D’Amico 2006) and the cultural contexts that influenced Rossetti’s illness experiences (Harrison 2007; Hu 2010; Blair 2006; and Kent 1996). |

| 4 | Rossetti biographers and critics have noted that Rossetti’s treating physician, Dr. Charles Hare, was still alive when Mackenzie Bell was writing the first full biography of Christina Rossetti, and he “gave his statement at first hand” to Bell. Hare reportedly said that the adolescent Rossetti was at that time “more or less out of her mind (suffering, in fact, from a form of insanity, I believe, a kind of religious mania)”. It was decided that this fact would be omitted from Bell’s biography “for obvious reasons […], tho’ the doctor’s good faith was not impugned” (Kohl 1968, pp. 423–24). However, the accuracy of this report has recently come under question. In a recent brief article, Simon Humphries for the first time brings into the biographical record Dr. Hare’s memoranda sent to Bell on 2 November 1896. Humphries probes the evidence, exposes misattributions, and very usefully corrects and clarifies this attribution to Dr. Hare of a diagnosis that the adolescent Rossetti suffered from “religious mania” (Humphries 2017). |

| 5 | For a discussion of the culturally constructed meaning attached to tuberculosis, see Susan Sontag’s Illness as Metaphor (Sontag 1978). |

| 6 | Marsh also suggests that the persistent cough may have been a tussis nervosa, a psychosomatic symptom. |

| 7 | Harrison speculates that Rossetti’s depression was the product of mid-Victorian ideology and rigid suppression of sexual desire (Harrison 2007, p. 422). |

| 8 | Many authoritative lists of Graves’ disease symptoms do not include difficulty swallowing or a choking sensation, but recent research reports that dysphagia is a rare manifestation of Graves’ disease (Chiu et al. 2004). The relationship of nervous symptoms to Graves’ disease has been debated. During the 1890s, doctors saw the nervous derangement as part of Graves’ disease and considered a whole range of “nervous disturbances” and “hysterical symptoms” as part of the disease presentation (Reynolds 1890, p. 1056). The authors are grateful to Diane D’Amico and Bonnie Cross for generously sharing their research on the history of Graves’ disease. |

| 9 | Stress is one of the environmental factors that can precipitate onset of Graves’ disease in a genetically predisposed individual. Toxins (including cigarette smoking), infections, hormones, and ageing are other factors that can play a role. Both infection and stress could have contributed in the case of Rossetti’s Graves’ disease. |

| 10 | The authors would like to thank Marjorie Stone (Dalhousie University) for bringing Broom’s work to our attention and for many inspiring and productive conversations on literature and medicine. |

| 11 | Although the Rossetti family record characterizes Graves’ disease as “rare,” it is the most common type of hyperthyroidism, with an incidence of 22–25 per 100,000 people in the United Kingdom. The female to male ratio is 3.9 to 1 (Hussain et al. 2017). The Rossetti family referred to the condition as both “Dr. Graves’s disease” and as “exophthalmic bronchocele”. Other names used today include “Basedow’s disease”, “autoimmune thyrotoxicosis”, “autoimmune hyperthyroidism”, and “toxic diffuse goiter”. |

| 12 | Graves’ description was first presented in clinical lectures delivered at the Meath Hospital during the session of 1834–35 and was published under the title “Newly observed affection of the thyroid gland in females” in the London Medical Surgical Journal (Graves 1835) and later republished in 1843 in Graves’ influential book A System of Clinical Medicine (1843). For the history of Graves’ disease, see Volpé and Sawin (2000), Weetman (2003), and Medvei (1993). |

| 13 | Stokes also notes that this condition occurs most often in females, and he associates the disease with a sensitive and nervous temperament and with “hysteria, neuralgia, or uterine disturbance” (Stokes 1855, p. 312). |

| 14 | This vague reference to “internal complaint” could refer to gastrointestinal hypermotility resulting in diarrheal-like stool or possibly to alterations in Rossetti’s menstrual cycle, both of which can occur with Graves’ disease. Such uncertainties highlight one of the limitations of the substantial written record—a sense of privacy and decorum that would have prevented Christina and others from describing some symptoms in detail. |

| 15 | Through this period, Rossetti continued to suffer from other sundry problems, a bad tooth, ear-aches, an abscess in her mouth that made her face swell, a cold, a hacking cough, and styes. |

| 16 | Today, thyroid storm, atrial fibrillation, and myocardial infarction would be considered serious risks. |

| 17 | Sir William Jenner had been known to Christina since 1854, but there is no record of Jenner attending her professionally until the 1860s; he continued treating her until his retirement in 1890 (Marsh 1994, p. 375). |

| 18 | “Dr. Fox,” William Michael wrote in his diary, “has seen only two cases of it (one of which he treated successfully), and Sir W. Jenner, as I understand, had also only seen two cases” (W.M. Rossetti 1977, p. 130). |

| 19 | Thomas Spencer Wells was surgeon to Queen Victoria’s household 1863–1896 (W.M. Rossetti 1977, p. 69 n3). |

| 20 | This is known as the Wolff–Chaikoff effect, whereby large doses of iodine will temporarily inhibit production of thyroid hormone. This effect is still taken advantage of today in the ICU setting for patients in a clinical thyroid storm. See Leung and Braverman (2014). |

| 21 | Digitalis is a medication that is still in use today, in the form of digoxin, for the symptomatic management of low ejection heart failure and atrial fibrillation. In Graves’ disease, it is possible to develop both of these states as a direct result of the hyperthyroid state. Digoxin can improve contractility and left ventricular ejection fraction, decrease sympathetic tone, and increase vagal tone. |

| 22 | William Michael records, “Maria was talking the other day to her surgical friend Mr Curgenvan about Christina’s illness. He says that he quite understands what it is, from the various statements he has heard about it. It is the malady called Dr. Graves’s disease, or exophthalmic bronchocele—very rare. A Dr. Cheadle has treated some cases successfully. The disease is (as we had been previously told) in the circulation of the blood: some congestion hence arising causes the swelling at the throat” (W.M. Rossetti 1977, p. 144). |

| 23 | Graves’ disease is an autoimmune thyroid disease which is characterized by hyperthyroidism and the production of autoantibodies which bind to and activate the thyrotropin receptor (TRAb). As these antibodies wrongfully overstimulate the thyroid gland, the synthesis of thyroid hormone becomes autologous, causing systemic disease. See McIver and Morris (1998). |

| 24 | In 1886, Paul Julius Moebious first proposed that hypersecretion from the thyroid gland could cause the disorder (Weetman 2003, p. 115). |

| 25 | Rossetti sent the manuscript to her publisher Alexander Macmillan on 4 February 1874 (C. Rossetti 1997–2004, vol. 2, p. 7). |

| 26 | Perhaps some lingering sensitivity on Rossetti’s part to her own altered appearance can be read in her description of Maggie’s thoughts on meeting the deformed boy: Maggie “tried not to stare, because she knew it would be rude to do so; though none the less amazed was she at his aspect” (C. Rossetti 1998, p. 147). |

| 27 | In “The Sisterhood of Self,” Winston Weathers uses Freudian psychoanalytic terms to discuss Rossetti’s lyric poetry as an allegorical sketch of “the fragmented self moving or struggling toward harmony and balance,” a theme which Weathers describes as “one of the major motifs in her mythic fabric” (Weathers 1965, p. 81). Georgina Battiscombe describes Rossetti’s life as one of strain and suffering caused by continual internal conflict between two sides of Rossetti’s personality, each side determined by one of two contesting cultural influences, English and Italian (Battiscombe 1981, pp. 13–14). More recently, Suzanne Waldman has described self-division as a key structure in Rossetti’s poems. Following Lacan, Waldman sees this split as a cleavage, not between the unconscious and the conscious, but between the imaginary and symbolic orders; for Christina, this duality is a Christian conflict within which the subject aspires to heaven while clinging to the world (Waldman 2009, p. 1). Marsh, meanwhile, observes that self-loathing is a recurrent theme in Rossetti’s poetry, noting that “the sense of a ‘dark double’ within her soul (‘traitor,’ ‘deadliest foe’) lay close to the surface of Christina’s personality” (Marsh 1994, p. 307). |

| 28 | Ague is a medical term indicating a febrile state involving alternating periods of fever, sweating, chills, and shivering. |

| 29 | “‘If thou sayest, behold, we knew it not,’” “The Thread of Life,” and “An Old World Thicket” (C. Rossetti 2001, pp. 329–36). |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).