@Shakespeare and @TwasFletcher: Performances of Authority

Abstract

1. Introduction

Although the relationship between the ‘original’ and the ‘reproduction’ is already complex in the case of Shakespeare, these complications are intensified by digital technologies and their advanced reproductive capabilities. In the swirl of the assemblages that (re)animate Shakespeare’s legacy, we can no longer say with confidence what is original and what is reproduced—or reincarnated. In playing around with death and animation, I also pick up Danielle Rosvally’s identification of @Shakespeare as a ‘digital ghost’; in engaging with and extending Rosvally’s terminology, I also engage with the longer critical history of literary and dramatic ‘ghosting’, including the the work of Benjamin, Jacques Derrida, Marjorie Garber, Herbert Blau, and Marvin Carlson on the afterlives of art (and specifically performances) as processual ‘hauntings’ that continuously carry forward into the present (Rosvally 2017).[t]he here and now of the original underlies the concept of its authenticity […] The whole sphere of authenticity eludes technological—and of course not only technological—reproduction. But whereas the authentic work retains its full authority in the face of a reproduction made by hand, which it generally brands a forgery, this is not the case with technological reproduction.

2. ‘Tell Them You’re Me!’ Ghostly Identities on Twitter

3. Theorising Authority, Identity, and Anonymity Online

In other words, marginalised bodies online are not allowed to forget their colour, gender, orientation, religion, ability, or class in the way that “normalised” bodies like Jernigan’s might. To appear to be anything other than an idealised male body online is to be scrutinised, marginalised, cryosectioned, examined under a social microscope. While we might argue that movements such as #MeToo are beginning to change this landscape, statistical data continues to show that women are ‘more than twice as likely to experience severe forms of abuse such as stalking or sexual harassment’ online (Veletsianos et al. 2018, p. 4691). This is, of course, an intersectional issue, with women of colour and trans women (for example) experiencing significantly higher rates of abuse. Veletsianos et al. also note that ‘women who are in the public eye or who use technology to promote their work—such as scholars—are placed at even greater risk’ of serious abuse in online spaces. (Veletsianos et al. 2018, p. 4691; see also Duggan 2014).[i]n other words, given that the majority of computer scientists in the early years of the public Internet were (and are today) male, bodies in cyberspace will be described, represented, and recognized—and, one can extrapolate, addressed—according to the “preexisting codes for body” ([Stone] 14), that is, for gendered bodies, that proliferate in real-world spaces.

By putting the inmate in a state of constant visibility and making them aware that they are always potentially watched, the power of the invisible guardians is consolidated and assured. In this sense invisibility does confer power, but perhaps only to those who already hold it.He [sic] is seen, but he does not see; he is the object of information, never a subject in communication. The arrangement of his room, opposite the central tower, imposes on him an axial visibility; but the divisions of the ring, those separated cells, imply a lateral invisibility. And this invisibility is a guarantee of order. […] Hence the major effect of the Panopticon: to induce in the inmate a state of conscious and permanent visibility that assures the automatic functioning of power.

4. Fannish Authority on Twitter

5. @Shakespeare: Performing Implicit Authority

This ‘bit of online real estate’ makes the account more accessible than similar efforts such as @Wwm_Shakespeare. And yet, for all its visibility—discoverability, findability—the account is stringent in its maintenance of anonymity. In my interviewee’s words,Well I think part of it is simply the Twitter handle. The @shakespeare address is a small, strategic bit of online real estate, and it means that some people unwittingly evoke us just by adding the @.

The ‘ghost-tweeter(s)’ capitalise upon that secret, and my interviewee suggests that the account has been popular—and relatively immune to ‘trolling’ and abuse—partly because it ‘assumes Shakespeare’s authority instead of grasping for it’ (@Shakespeare 2017, my emphasis). This is a powerful assumption in that it encompasses not merely the continuing cultural cache of Shakespeare’s canon, but the capital wielded by the entire ‘surfeit of Shakespeares’ (O’Neill 2018, p. 121), the coincidence of historical and cultural factors that define what ‘Shakespeare’ means in the present. As Fazel and Geddes remind us,… it’s part of the @Shakespeare DNA to keep the ghost-tweeter(s) anonymous. It has just always seemed funnier and more effective to commit to the fiction that this is really William Shakespeare. […] So one of the basic rules is that no one can find the tweeter(s) [sic] identities online. This is not a secret to everyone, but it is a secret to the Internet. (30 May 2017)

Scholars and particularly artists have long embraced the ‘possibility that history, even long dead history, does not have to remain static’ (Rosvally 2017, p. 162); the digital, however, makes these processes clearer, more transparent, and more accessible to intervention from a variety of actors. @Shakespeare, then, is one such actor, who intervenes in the continuous re-making of Shakespeare to stake its claim to the authority contained therein.what is collectively represented or defined as Shakespeare is continuously being reminagined and reconstructed in accordance with the affordances of the medium in which he appears and the purposes to which he is put to task.

Aside from the geeky satisfaction of a joke (or, in this case, a whole series of jokes) about John Donne, Christopher Marlowe, Ben Jonson, and William Shakespeare hanging out in Los Angeles together, this tweet trades on the reader’s knowledge of Elon Musk’s electric car and its functionality as much as niche early modern authors. This is Shakespeare’s—and @Shakespeare’s—‘uncanny temporality’ in action: a joke groaning under the weight of 400 years (O’Neill 2018, p. 122). But whereas knowledge of how a Tesla Model S functions might be considered popular (if not yet common) knowledge in 2017, it is perhaps less likely that the average Twitter user would recognise and understand enough about Donne, Marlowe, and/or Jonson to be in on the joke.Donne hath rented us a Tesla Model S. It turns itself on as Marlowe gets behind the wheel.Jonson looks for a ghost.There are 4.#ShakesLA (24 February 2017)

@Shakespeare: ‘On the boardwalk at Venice Beach, asking passers by of [sic] they want to wage on the Three Caskets game.’ #ShakesLA

The success of the jokes, here, relies on the reader’s knowledge of—at a minimum—The Merchant of Venice and The Winter’s Tale, making it a satisfying in-joke for Shakespeare scholars, practitioners, and enthusiasts. The account trades on this level of engagement from those who know Shakespeare’s works inside and out, using even his most obscure plays to make topical jokes: ‘Don’t let Coriolanus defecting to the Volscians and marching on Rome distract you from the big things’ (20 May 2017). This is a performance not only of Shakespearean authority—that is, a performance of an ‘author-ized’ (Fazel and Geddes 2015) Shakespearean self—but also a performance of fannish authority, that manipulates and reconstitutes both the historical figure of Shakespeare and his canon to accommodate new situations, relationships, and narratives.@_BenJonson_: ‘(We let @Shakespeare do this. It keeps him from running up to every spray-painted statue performer & crying “Music! Awake her!”) #ShakesLA’ (25 February 2017).

6. @TwasFletcher: Transforming Shakespeare’s Authority

‘The #FletcherSunday tag is amazing because after 5 centuries, his works are still treasured and performed’ (20 September 2015).

‘Okay he just referred to Fletcher as “J. Fletch” and thats [sic] where I draw the line’ (30 September 2015).

These examples are particularly relevant in their co-option of #ShakespeareSunday, a weekly meme tradition created by fans of the BBC Shakespeare histories series The Hollow Crown (@HollowCrownFans). #ShakespeareSunday encourages followers to tweet their favourite Shakespeare quotations, every Sunday, ‘often unified around specified themes or commemorative events’ that ‘enable users to demonstrate their knowledge of Shakespeare’ (Mullin 2018, pp. 214–15).13 @TwasFletcher’s intervention here is therefore doubly significant for its interruption and interpolation of a longstanding (in Twitter terms) and enormously popular Shakespeare meme.‘There are so many awesome #FletcherSunday quotes!’ (27 September 2015).

Unlike @Shakespeare, there is no cloak of anonymity around @TwasFletcher. Pasupathi does borrow Fletcher’s likeness under the auspices of @TwasFletcher, but only intermittently—and even when she does so, there is always a clear path back to her, the material fact of her brown, female body and her status as a professor in a notoriously old, white, and male field. For those in the know, it becomes a kind of joke: we interact with @TwasFletcher knowing that, on some level, we are interacting with Pasupathi. There is no such awareness embedded in @Shakespeare: most who interact with the account do not know who its authors are, and there is no trail back to them through the account bio or other public-facing record. It is not possible to have the same level of awareness, the same sense of interacting with a person that @TwasFletcher provides, despite the fact that @TwasFletcher is primarily automated (a bot) and @Shakespeare’s content is user-generated.What does it look like when we replace Shakespeare with Fletcher, if only in digital spaces? How do people respond when they find a name they don’t expect? Do Fletcher’s lines […] sound worthy of being passed around?

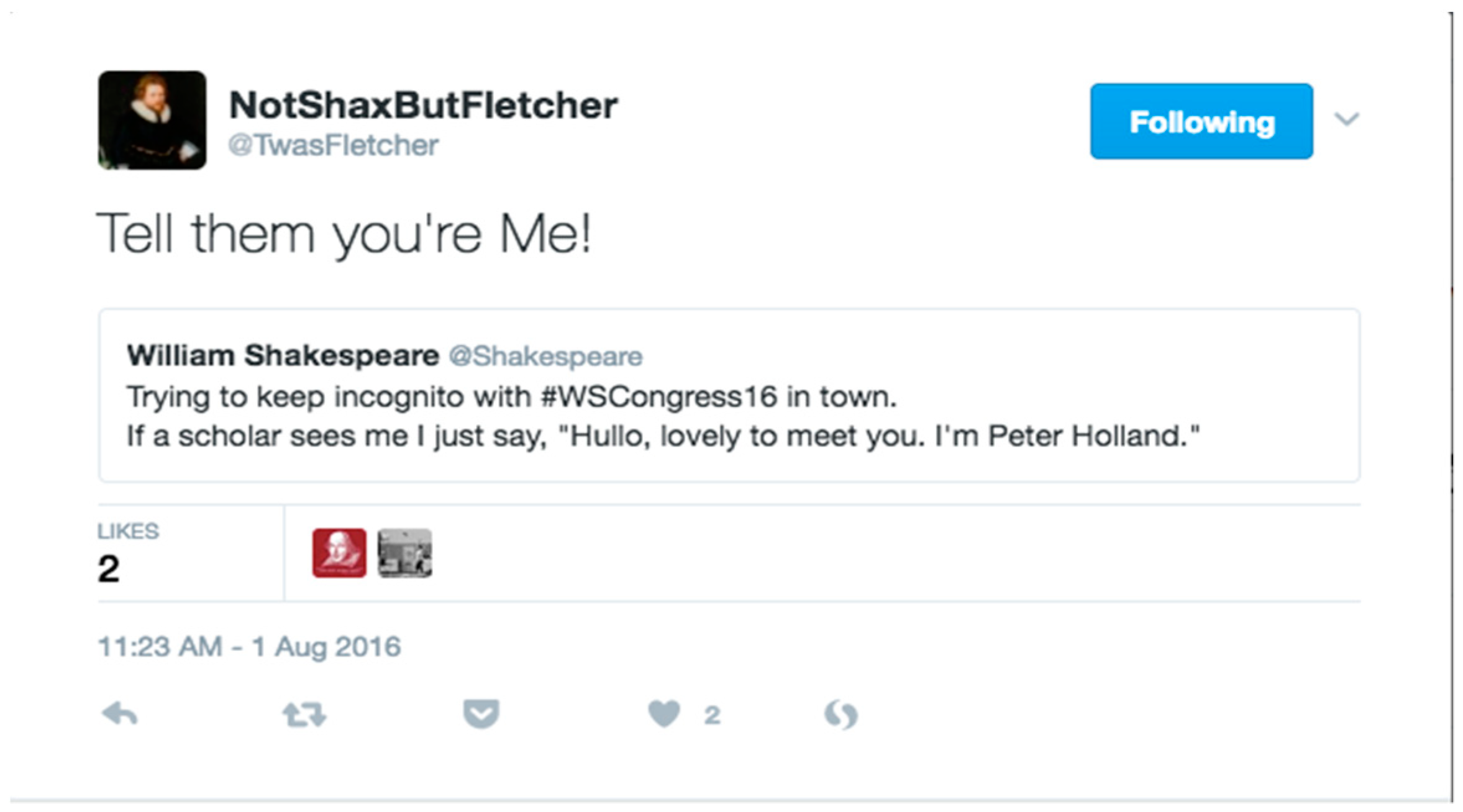

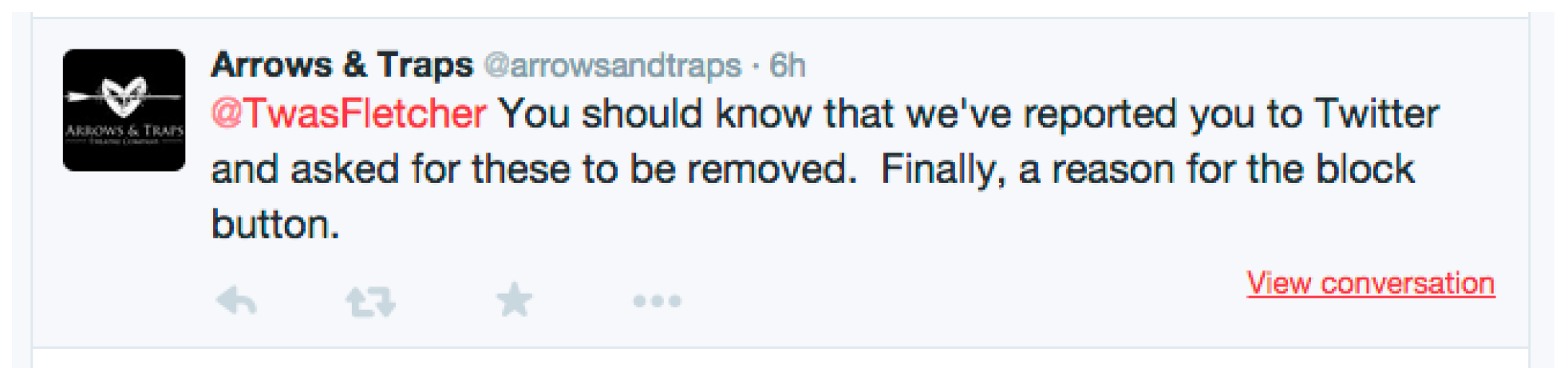

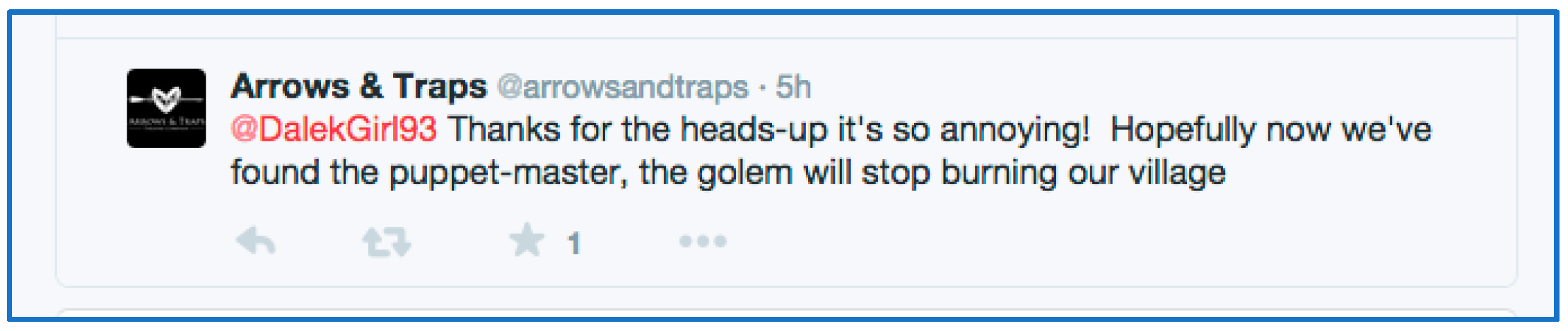

They also likened Pasupathi to a ‘golem’ ‘burning our village’ (Figure 3):‘@TwasFletcher You should know that we’ve reported you to Twitter and asked for these to be removed. Finally, a reason for the block button.’

In challenging Shakespeare’s authority via a lesser-known early modern playwright, Pasupathi also challenges the boundaries of good taste. This perceived assault on the boundaries of Shakespeare’s cultural authority is significant for its connection to Pasupathi as much as its affiliation with Fletcher: she represents (and, through her bot, enacts) a challenge to the status quo of Shakespeare Studies and pop culture Shakespeare alike.The boundaries of “good taste,” then, must constantly be policed; proper tastes must be separated from improper tastes; those who possess the wrong tastes must be distinguished from those whose tastes conform more closely to our own expectations. Because one’s taste is so interwoven with all other aspects of social and cultural experience, aesthetic distaste brings with it the full force of moral excommunication and social rejection. “Bad taste” is not simply undesirable; it is unacceptable.

Of course, @Shakespeare’s anonymity is nothing intentionally sinister or underhanded: the ghost-tweeters assert that it is simply ‘more fun’ to pretend that Shakespeare himself is on Twitter. In this case, it means hiding in plain sight. The managers of @Shakespeare exist: they are flesh-and-blood humans who nonetheless are invisible to most who interact with the account. The lack, in this case, of a tangible, embodied person to whom we can attach the activities of @Shakespeare allows Shakespeare (the man, the myth, the legend) to haunt @Shakespeare more thoroughly—and, in doing so, entrench the image of Shakespeare as man. As Rosvally puts it, @Shakespeare ‘generates creative fictions about the figure of Shakespeare that ask users to envision the ghost’s presence in their daily lives’ (Rosvally 2017, p. 156). @TwasFletcher does something similar, but with an additional layer of haunting: by reconfiguring tweets about Shakespeare as tweets about Fletcher, it performs an alternative history that interpolates itself into our horizon of expectation. John Fletcher’s haunting of @TwasFletcher is of a totally different kind, both because Fletcher lacks Shakespeare’s ubiquity and because Pasupathi interrupts the ghostly presence, layering herself between Fletcher and @TwasFletcher in deliberate and significant ways.Many works of cyborg discourse envision a near-future of human-machine (ranging from complete merging to entrenched warfare between the two parties) in which “human” is equated with femaleness. […] This is a persistent trope in visions of the future that circulated during the 1980s and 1990s: as the flesh appears ever weaker and decreasingly mandatory in the face of technology’s galloping developments, women become the “natural preserve” of human embodiment, the memory-keepers of, and advocates for, the importance and significance of physicality.

7. Conclusions: Remediating Ghostly Authority

Framed in this way, we might think about @TwasFletcher as a kind of carnival version of @Shakespeare—and @Shakespeare, in turn, as a carnival Shakespeare. As De Kosnik and Donald Theall have argued, it is easy to connect internet cultures to the idea of the carnival because Marshall McLuhan’s theory of the global village echoes Mikhail Bakhtin:recreate Shakespearean and literary ontologies (What is Shakespeare? What is literary?), genres and media (Where do we find Shakespeare? What elements do we consider Shakespeare?), motives and audiences (For whom and to whom is this Shakespeare?) and markets (Who is capitalizing from or on Shakespeare, and in what ways?).

The other key to carnival is that it is a temporary state, when the laws that normally apply are sub/inverted and topsy-turvy rules. In this sense, we can think of @TwasFletcher as a kind of brief, carnivalesque inversion that ‘infuse[s] its participants with a conviction that the prevailing social and cultural order and structure need not always prevail’ (De Kosnik 2016, p. 177). Pasupathi’s experiment embodies the carnivalesque in its limited time frame and in its gleeful subversion of the Shakespeare-centric narrative of early modern drama and culture. The identity-swapping that takes place in the #WSCongress16 tweet discussed above offers a potent example: not only does Fletcher (lesser-known, less exalted early modern playwright) co-opt the authority of Shakespeare (shining star, ubiquitous early modern playwright), but—through this topsy-turvied relationship between Fletcher and Shakespeare—Pasupathi turns Shakespearean academic hierarchy on its head as well, tugging on the authority of Peter Holland and broadcasting her own voice in the process.Carnival does not know the footlights, in the sense that it does not acknowledge any distinction between actors and spectators […]. Carnival is not a spectacle seen by the people; they live in it, and everyone participates because its very idea embraces all people.

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- @Shakespeare. 2017. Twitter Direct Message to the author. May 30. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin, Walter. 2002. The Work of Art in the Age of Its Reproducibility. In Walter Benjamin: Selected Writings. Edited by Howard Eiland and Michael W. Jennings. Translated by Edmund Jephcott, Howard Eiland, and et al.. Cambridge: Belknap Press, pp. 101–33, First publish 1936. [Google Scholar]

- Blackwell, Anna. 2018. Shakespearean Celebrity in the Digital Age: Fan Cultures and Remediation. London: Palgrave. [Google Scholar]

- Bolter, Jay David, and Richard Grusin. 1999. Remediation: Understanding New Media. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Mark. 2016. Emma Rice to Step Down as Artistic Director at Shakespeare’s Globe. Guardian. October 25. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/stage/2016/oct/25/emma-rice-step-down-artistic-director-shakespeares-globe (accessed on 22 February 2019).

- Calbi, Maurizio. 2013. “He Speaks … Or Rather … He Tweets”: The Specter of the “Original”, Media, and “Media-Crossed” Love in Such Tweet Sorrow. In Spectral Shakespeares: Media Adaptations in the Twenty-First Century. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 137–62. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, Barry R. 2019. Francis Bacon’s Contribution to Shakespeare: A New Attribution Method. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- De Kosnik, Abigail. 2016. Rogue Archives: Digital Cultural Memory and Media Fandom. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Duggan, Maeve. 2014. Online Harassment. The Pew Research Centre: Internet, Science and Tech. Available online: http://assets.pewresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/14/2014/10/PI_OnlineHarassment_72815.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2019).

- Fazel, Valerie M., and Louise Geddes. 2015. ‘Give Me Your Hands If We Be Friends’: Collaborative Authority in Shakespeare Fan Fiction. Shakespeare 12: 274–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazel, Valerie M., and Louise Geddes. 2017. Introduction: The Shakespeare User. In The Shakespeare User: Critical and Creative Appropriations in a Networked Culture. Edited by Valerie M. Fazel and Louise Geddes. London: Palgrave Macmillian, pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault, Michel. 1995. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. New York: Vintage Books. [Google Scholar]

- Furness, Hannah. 2016. Emma Rice: ‘A lot of Shakespeare feels like medicine’. Telegraph. January 16. Available online: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/theatre/actors/emma-rice-a-lot-of-shakespeare-feels-like-medicine/ (accessed on 22 February 2019).

- Harvey, Kerric. 2014. Encyclopedia of Social Media and Politics. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Iyengar, Sujata. 2017. Shakespeare Transformed: Copyright, Copyleft, and Shakespeare After Shakespeare. Shakespeare après Shakespeare [Shakespeare After Shakespeare]. Paper presented at Société Française Shakespeare Conference, Paris, France, January 20–23. Edited by Anne-Valérie Dulac and Laetitia Sansonetti. Available online: https://journals.openedition.org/shakespeare/3852 (accessed on 1 February 2019).

- Jenkins, Henry. 2006. Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide. New York: NYU Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, Henry. 2013. Textual Poachers: Television Fans and Participatory Culture. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kidnie, Margaret Jane. 2009. Shakespeare and the Problem of Adaptation. Abingdon: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Lonergan, Patrick. 2016. Theatre & Social Media. London: Palgrave. [Google Scholar]

- Moberly, David C. 2018. ‘Once More to the Breach!’: Shakespeare, Wikipedia’s Gender Gap, and the Online, Digital Elite. In Broadcast Your Shakespeare: Continuity and Change Across Media. Edited by Stephen O’Neill. London: Bloomsbury Arden, pp. 87–104. [Google Scholar]

- Mullin, Romano. 2018. Tweeting Television/Broadcasting the Bard: @HollowCrownFans and Digital Shakespeares. In Broadcast Your Shakespeare: Continuity and Change Across Media. Edited by Stephen O’Neill. London: Bloomsbury Arden, pp. 207–26. [Google Scholar]

- Murthy, Dhiraj. 2013. Twitter: Social Communication in the Twitter Age. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura, Lisa. 2008. Digitizing Race: Visual Cultures of the Internet. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill, Stephen. 2018. Shakespeare’s Digital Flow: Humans, Technologies and the Possibilities of Intercultural Exchange. Shakespeare Studies 46: 120–33. [Google Scholar]

- Pasupathi, Vimala C. 2015. #NotShaxButFletch. Available online: https://vcpasupathi.wordpress.com/current-research/replaceshaxwithfletch/ (accessed on 1 February 2019).

- Pasupathi, Vimala C. 2017. Digital Fletcher. Paper presented at the MLA Convention, Philadelphia, PA, USA, January 5–8. [Google Scholar]

- Rice, Emma. 2018. A Letter from Artistic Director Emma Rice. Shakespeare’s Globe Blog. April 19. Available online: https://blog.shakespearesglobe.com/tagged/A-Letter-From (accessed on 22 February 2019).

- Rose, Gillian. 1993. Feminism and Geography: The Limits of Geographical Knowledge. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rosvally, Danielle. 2017. The Haunted Network: Shakespeare’s Digital Ghost. In The Shakespeare User: Critical and Creative Appropriations in a Networked Culture. Edited by Valerie M. Fazel and Louise Geddes. London: Palgrave Macmillian, pp. 149–66. [Google Scholar]

- Roth, Yoel. 2018. Automation and the Use of Multiple Accounts. Twitter Developer Blog. February 21. Available online: https://blog.twitter.com/developer/en_us/topics/tips/2018/automation-and-the-use-of-multiple-accounts.html (accessed on 1 February 2019).

- Saco, Diana. 2002. Cybering Democracy: Public Space and the Internet. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, Sanjay. 2013. Black Twitter?: Racial Hashtags, Networks and Contagion. New Formations: A Journal of Culture/Theory/Politics 78: 46–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Emma. 2017. Shakespeare: The Apex Predator. TLS Online. May 4. Available online: https://www.the-tls.co.uk/articles/public/shakespeare-apex-predator/ (accessed on 1 February 2019).

- Strauss, Valerie. 2015. Teacher: Why I Don’t Want to Assign Shakespeare Anymore (Even Though He’s in the Common Core). Washington Post. June 13. Available online: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/answer-sheet/wp/2015/06/13/teacher-why-i-dont-want-to-assign-shakespeare-anymore-even-though-hes-in-the-common-core/??noredirect=on (accessed on 1 February 2019).

- Veletsianos, George, Shandell Houlden, Jaigris Hodson, and Chandell Gosse. 2018. Women Scholars’ Experiences with Online Harassment and Abuse: Self-Protection, Resistance, Acceptance, and Self-Blame. New Media & Society 20: 4689–708. [Google Scholar]

- Vint, Sherryl. 2007. Bodies of Tomorrow: Technology, Subjectivity, Science Fiction. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | From its founding until 2017, Twitter limited each “tweet” to 140 characters. |

| 2 | For more complete introductions to Twitter and its affordances, see Dhiraj Murthy (2013), Twitter: Social Communication in the Twitter Age, Cambridge: CUP; Maurizio Calbi (2013), “He Speaks … Or Rather … He Tweets”: The Specter of the “Original,” Media, and “Media-Crossed” Love in Such Tweet Sorrow. In Spectral Shakespeares: Media Adaptations in the Twenty-First Century. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 137–62; and Romano Mullin (2018), ‘Tweeting Television/Broadcasting the Bard: @HollowCrownFans and Digital Shakespeares’. In Broadcast Your Shakespeare: Continuity and Change Across Media. Edited by Stephen O’Neill. London: Bloomsbury Arden, pp. 207–26. |

| 3 | Mark Rylance, former Artistic Director of Shakespeare’s Globe, recently wrote to Foreword to a forthcoming book by Barry R. Clarke on Francis Bacon’s Contribution to Shakespeare: A New Attribution Method (Clarke 2019). See M.J. Kidnie (2009), Shakespeare and the Problem of Adaptation for a more complete discussion of the role of ‘authenticity’ in reviews of Shakespeare productions. |

| 4 | Unlike many major conferences (including Shakespeare Association of America (SAA)), the 2016 World Shakespeare Congress did not advertise a specific social media policy. SAA first published a detailed social media policy for conference delegates in 2015, but this was substantially updated in 2017. See http://www.shakespeareassociation.org/about/saa-policies/social-media-guidelines/. |

| 5 | The language of the fleshly, ‘real’ body as ‘meat’ originates with William Gibson’s Neuromancer (1984), often considered the first and certainly one of the most influential cyberpunk novels of the 1980s and 90s. In the novel, the offline world is referred to (derisively) as the ‘meatspace’, in contrast to ‘cyberspace’. |

| 6 | We might extend ‘women’ here to include other marginalised identities. |

| 7 | See also Nakamura on ‘Measuring Race on the Internet: Users, Identity, and Cultural Difference in the United States’ in Digitizing Race: Visual Cultures of the Internet, pp. 171–201. |

| 8 | Patrick Lonergan (2016) gives a detailed account of Gardiner’s use of false identities on Twitter in Theatre & Social Media, pp. 1–3. |

| 9 | See Anna Blackwell (2018), Shakespearean Celebrity in the Digital Age: Fan Cultures and Remediation. London: Palgrave, especially Chapter 3: ‘Performing the Shakespearean Body: Tom Hiddleston Onstage and Online’. |

| 10 | ‘Findability’ is an industry term used to describe the discoverability or availability of a given piece of digital culture. See, e.g., Kerric Harvey (ed.), Encyclopedia of Social Media and Politics. London: Sage, (Harvey 2014). |

| 11 | Shakespeare’s Globe announced the appointment of Emma Rice as their third Artistic Director on 1 May 2015. This was a controversial choice from the start, with Rice confessing to the press that she had previously directed only one Shakespeare play (Cymbeline) and that reading Shakespeare’s plays often ‘left her “very sleepy”’ (Furness 2016). In October 2016, barely six months after Rice had taken up her post, the Globe announced that she would be stepping down after her second season. The announcement, exacerbated by the reasoning given in the Globe’s press release (a desire to return to ‘shared light’ productions ‘without designed sound and light rigging’ (Brown 2016)), triggered enormous and immediate backlash on Facebook and Twitter, with #EmmaRice trending as both supporters and detractors weighed in. Rice later published a pull-no-punches letter to her successor, which addressed some of the controversy and was published to the Globe’s blog (Rice 2018). |

| 12 | Following the Cambridge Analytica data mining scandal, and investigations into foreign governments’ potential interference in the 2016 Presidential election in the United States and the EU referendum in the United Kingdom, Twitter updated their ‘Automation Rules’ in January 2018 (Roth 2018). |

| 13 | For a more thorough account of the relationship between @HollowCrownFans and #ShakespeareSunday, see (Mullin 2018). |

| 14 |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Williams, N.J. @Shakespeare and @TwasFletcher: Performances of Authority. Humanities 2019, 8, 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/h8010046

Williams NJ. @Shakespeare and @TwasFletcher: Performances of Authority. Humanities. 2019; 8(1):46. https://doi.org/10.3390/h8010046

Chicago/Turabian StyleWilliams, Nora J. 2019. "@Shakespeare and @TwasFletcher: Performances of Authority" Humanities 8, no. 1: 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/h8010046

APA StyleWilliams, N. J. (2019). @Shakespeare and @TwasFletcher: Performances of Authority. Humanities, 8(1), 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/h8010046