Dalmatians and Dacians—Forms of Belonging and Displacement in the Roman Empire

Abstract

:1. Alburnus Maior, Roman Dacia

1.1. Displacement or Labour Mobility?

1.2. ‘Illyrians’ in Alburnus Maior

Maximus Batonis puellam nomine | Passiam, sive ea quo alio nomine est an|norum sex [above line: circiter p(lus) m(inus) empta sportellaria] emit mancipioque accepit | de Dasio Verzonis Pirusta ex Kaviereti[o] | * ducentis quinque. … dari fide rogavit | Maximus Batonis, fide promisit Dasius || Verzonis Pirusta ex Kaviereti[o]. Proque ea puella, quae s(upra) s(cripta) est, * ducen|tos quinque accepisse et habere | se dixit Dasius Verzonis a Maximo Batonis …

Maximus son of Bato has bought and accepted as a mancipium a girl by name Passia, or if she is (known) by any other name, m(ore or) l(ess) around six years old, having been bought as a foundling, for 205 (denarii), from Dasius son of Verzo, a Pirustian from Kavieretium. … Maximus the son of Bato asked to be given in faith, Dasius son of Verzo a Pirustian from Kavieretium promised in faith. Dasius son of Verzo said that he received and has for this girl, w(ho) i(s) w(ritten) a(bove), 250 denarii from Maximus son of Bato. Done at Kartum on the 16th day before the Kalends of April when (emperor) Titus Aelius Caesar Antoninus Pius and Bruttius Praesens were consuls (for the second time)… 19

1.3. Internal Divisions?

D(is) M(anibus) | Dasas Liccai (filius) | Del(mata) k(astello) Starvae | vixit an(nis) XXXV |5 pos(uerunt) Beucus | Sarius et ḌẠ[…] | […]i heredes b(ene) m(erenti).

To the spirits of the dead. Dasas, son of Liccaius, Dalmatian, from the fortified settlement (kastellum) of the Starvae, lived 35 years. The heirs Beucus, Sarius, and Da[-] set up (this epitaph), well-deserving.

1.4. Shared Experiences

1.5. Polyonymy

2. Krokodilo, Eastern Egyptian Desert

2.1. Dacians in the Desert

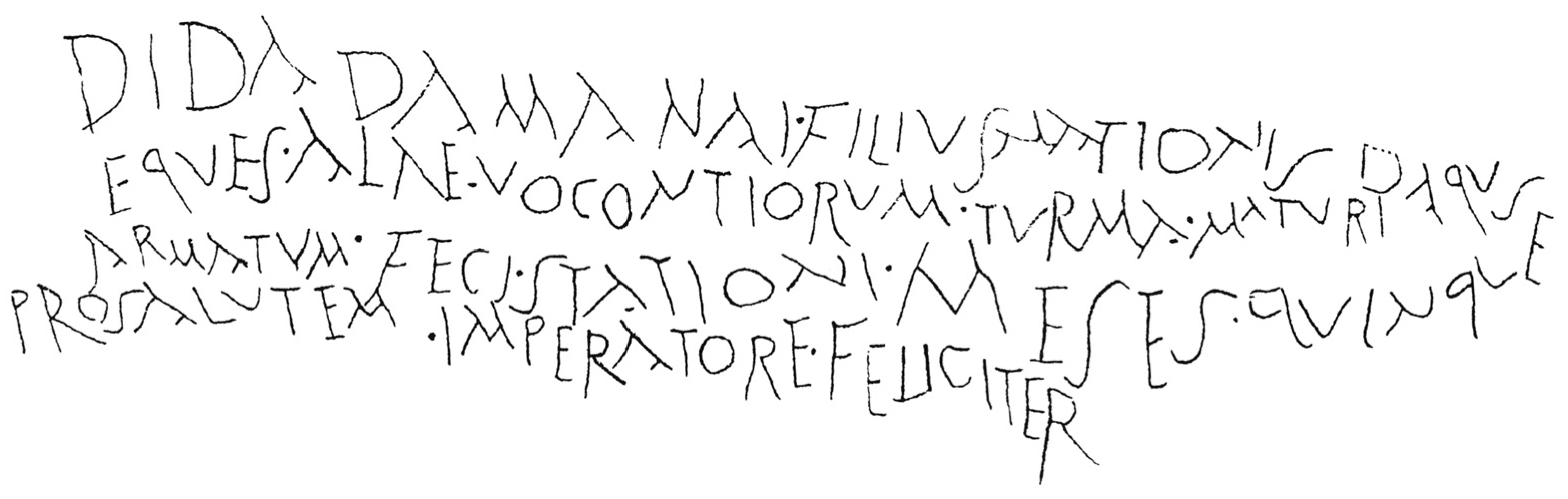

1Dida Damanai filius nationis Daqus |2 eques alae Uocontiorum turma Maturii |3 armatum(!) feci stationi (!) me(n)ses quinque |4 pro salute{m} imperatore (!) feliciter85

I, Dida, son of Damanaus, born in Dacia, cavalryman in the wing of the Vocontii, squadron of Maturus, stood five months under arms on post. Long live the emperor! Good luck!

Δεκιναις Καικεισα τῷ ἀδελφῷ χ(αίρειν). | ἀσπάζου Ζουτουλα καὶ Πουριδουρ. | ἐρωτῶ σε, Καικισα, σκύλητει | πρὸς ἐμὲ ἐπὶ χρίαν σου ἔχω· |5 ἐρωτῶ σε, ἔρχου ὡς πρὸς ἐμέ· | ἐγὼ ἤκουσα ὅτι πάντες οἱ Δάκες | ὑπάγουσιν μετὰ τοῦ ἡγεμόνος | ἰς Ἀλεξάνδ(ρειαν)· ἐὰν εἰδῇς ὅτι ὑπάγου|σιν ἰς Ἀλεξάνδ(ρειαν), γράψον ἰς Κόπτον |10 ἵνα ταχὺ ἀναβῇ. | ἔρρωσο.

“Dekinais to Kaikisa, his brother, greetings. Greet Zoutoula and Pouridour. I beg you, Kaikisa, move yourself and come because I have need of you. I beg you come and join me. I heard saying that all the Dacians are going with the prefect of Egypt to Alexandria. If you learned that they are going to Alexandria (with certainty), write to Koptos so that he(?) may hurry to go up(?). Farewell.”89

2.2. Shared Experience

2.3. Decebalus!

3. Conclusions

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AE | Année Epigraphique. |

| ChLA | Chartae Latinae Antiquiores. |

| CIL | Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum. |

| IDR | Inscriptiones Dacicae Romanae, Bucarest. |

| IGR | R. Cagnat et al., Inscriptiones Graecae ad Res Romanas pertinentes, Paris 1906–1927. |

| I. Ko. Ko. | A. Bernand, De Koptos à Kosseir, Leyden 1972. |

| ILJug | Inscriptiones Latinae quae in Iugoslavia inter annos MCMII et MCMLXX repertae et editae sunt, Ljubliana. |

| ILS | H. Dessau, Inscriptiones Latinae Selectae, Berlin 1892–1916. |

| O. Claud. | Mons Claudianus. Ostraca Graeca et Latina, Cairo. |

| O. Did. | Cuvigny (2012). |

| O. Ka. La. inv. | unpublished ostraka from Kaine Latomia (Umm Balad). |

| O. Krok. | Cuvigny (2005). |

| O. Krok. inv. | unpublished ostraka from Krokodilo (al-Muwayh). |

| LexMyth | W.H. Roscher (ed.). Ausführliches Lexikon der griechischen und römischen Mythologie, Leipzig 1884–1937. |

| RAC | Reallexikon für Antike und Christentum, Stuttgart. |

| RIB | Roman Inscriptions of Britain. |

Appendix A

References

- Alföldy, Géza. 1962. ΣΠΛAΥΝOΝ—Splonum. Acta Antiqua Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 10: 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Alföldy, Géza. 1963. Einheimische Stämme und civitates in Dalmatien unter Augustus. Klio 41: 187–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alföldy, Géza. 1965. Bevölkerung und Gesellschaft der Römischen Provinz Dalmatien. Budapest: Akadémiai Kiado. [Google Scholar]

- Alföldy, Géza. 1969. Die Personennamen in der römischen Provinz Dalmatia. Heidelberg: Carl Winter Universitätsverlag. [Google Scholar]

- Ardevan, Radu. 2004. Die Illyrier von Alburnus Maior. Herkunft und Status. In AD FONTES! Festschrift für Gerhard Dobesch zum fünfundsechzigsten Geburtstag am 15. September 2004. Edited by Herbert Heftner and Kurt Tomaschitz. Wien: Eigenverlag, pp. 593–98. [Google Scholar]

- Ardevan, Radu, and Criszina Crăciun. 2003. Le collegium Sardiatarum à Alburnus Maior. In Urbs Aeterna. Actas y Colaboraciones del Colloquio Internacional ‘Roma entre la Literatura y la Historia’. Homenaje a la Profesora Carmen Castillo. Edited by Concepcion Alonso del Real, Maria Pilar García Ruiz, Álvaro Sánchez-Ostiz Gutierrez, and José Bernadino Torres Guerra. Pamplona: EUNSA, pp. 227–40. [Google Scholar]

- Barnard, Alan, and Jonathan Spencer, eds. 2002. Encyclopedia of Social and Cultural Anthropology. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Birley, Anthony Richard. 1993. Marcus Aurelius: A Biography. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Bojanovski, Ivo. 1988. Bosna i Hercegovina u antičko doba. Sarajevo: Akademija nauka i umjetnosti Bosne i Hercegovine. [Google Scholar]

- Broux, Yanne. 2015. Double Names and Elite Strategy in Roman Egypt. Leuven: Peeters. [Google Scholar]

- Brun, Jean-Pierre, and Michel Reddé. 2006. L’architecture des praesidia et la genèse des dépotoirs. In La route de Myos Hormos. L’armée romaine dans le désert Oriental d’Égypte. Vol. 1 (FIFAO 48/1). Edited by Hélène Cuvigny. Le Caire: Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale, pp. 73–186. [Google Scholar]

- Bülow-Jacobsen, Adam, Hélène Cuvigny, Jean-Luc Fournet, Marc Gabolde, and Christian Robin. 1995. Les inscriptions d’Al-Muwayh. Bulletin de l’Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale 95: 103–24. [Google Scholar]

- Cauuet, Béatrice, and Călin Gabriel Tămaş. 2012. Les travaux miniers antiques de Roşia Montană (Roumanie). Apports croisés entre archéologie et géologie. In Minería y Metalurgia Antiguas. Visiones y revisiones. Homenaje a Claude Domergue. Edited by Almudena Orejas and Christian Rico. Madrid: Casa de Velázquez, pp. 219–41. [Google Scholar]

- Ciongradi, Carmen. 2009. Die römischen Steindenkmäler aus Alburnus Maior. Cluj-Napoca: Mega Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Ciongradi, Carmen, Anca Timofan, and Vitalie Bârcǎ. 2008. Eine neue Erwähnung des kastellum Starva in einer Inschrift aus Alburnus maior. Studium zu epigraphisch bezeugten kastella und vici im dakischen Goldbergwerksgebiet. Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 165: 249–66. [Google Scholar]

- Ciulei, Georges. 1983. Les triptyques de Transylvanie (Etudes juridiques). Zutphen: Terra Publishing Co. [Google Scholar]

- Combet-Farnoux, Bernard. 1981. Mercure romain, les ‘Mercuriales’ et l’institution du culte impérial sous le Principat augustéen. In Aufstieg und Niedergan der Römsichen Welt: Geschichte und Kultur Roms im Spiegel der Neueren Forschung II. Prinzipat. 17. Band. 1. Teilband. Religion (Heidentum: Römische Götterkulte, Orientalische Kulte in der Römischen Welt). Edited by Wolfgang Haase. Berlin: Walter De Gruyter, pp. 457–501. [Google Scholar]

- Coussement, Sandra. 2016. ‘Because I am Greek’. Polyonymy as an Expression of Ethnicity in Ptolemaic Egypt. Leuven: Peeters. [Google Scholar]

- Cuvigny, Hélène. 1996. The Amount of Wages paid to the quarry-workers at Mons Claudianus. Journal of Roman Studies 86: 139–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuvigny, Hélène. 2005. Ostraca de Krokodilô. La correspondence militaire et sa circulation (FIFAO 51). Le Caire: Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale. [Google Scholar]

- Cuvigny, Hélène, ed. 2012. Didymoi. Une garnison romaine dans le désert Oriental d’Égypte. II. Les textes (FIFAO 67). Le Caire: Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale. [Google Scholar]

- Czysz, Wolfgang, Karlheinz Dietz, Thomas Fischer, and Hans-Jörg Kellner. 1995. Die Römer in Bayern. Stuttgart: Konrad Theiss Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Daicoviciu, Constantin. 1958. Les “castella Dalmatarum”de Dacie: un aspect de la colonisation et de la romanisation de la province de Dace. Dacia 2: 259–66. [Google Scholar]

- Dalal, Ayham. 2017. Uncovering Culture and Identity in Refugee Camps. In Displacement and the Humanities: Manifestos from the Ancient to the Present. Edited by Elena Isayev and Evan Jewell. Special issue, Humanities 6: 61. [Google Scholar]

- Damian, Paul, ed. 2003. Alburnus Maior I. Bucharest: Muzeul Național de Istorie a României. [Google Scholar]

- Dana, Dan. 2003. Les Daces dans les ostraca du désert oriental de l’Égypte Morphologie des noms daces. Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 143: 166–86. [Google Scholar]

- Dana, Dan. 2007. Le nom du roi Décébale. Aperçu historiographique et nouvelles données. In Dacia Felix. Studia Miachaeli Bărbulescu oblata. Edited by Sorin Nemeti. Cluj-Napoca: Editura Tribuna, pp. 42–47. [Google Scholar]

- Dana, Dan. 2014. Onomasticum Thracicum (OnomThrac). Répertoire des noms indigènes de Thrace, Macédoine orientale, Mésies, Dacie et Bithynie (Meletemata 70). Athènes: Centre de recherche de l’antiquité grecque et romaine, Fondation nationale de la recherche scientifique. [Google Scholar]

- Dana, Dan, and Florian Matei-Popescu. 2006. Le recrutement des Daces dans l’armé romaine sous l’empereur Trajan. Une esquisse préliminaire. Dacia 50: 195–206. [Google Scholar]

- Dana, Dan, and Radu Zăgreanu. 2013. Les indigènes en Dacie romaine ou la fin annoncée d’une exception. Relecture de l’épitaphe CIL III 7635. Dacia 57: 145–59. [Google Scholar]

- Dészpa, Mihály Loránd. 2012. Peripherie-Denken. Transformation und Adaption des Gottes Silvanus in den Donauprovinzen (1.-4. Jahrhundert n. Chr.). Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Dušanić, Slobodan. 1999. The miner’s cults in Illyricum. Pallas 50: 129–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Džino, Danijel. 2010. Illyricum in Roman Politics 229 BC—AD 68. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Džino, Danijel. 2014. The formation of early imperial peregrine civitates in Dalmatia. (Re)constructing indigenous communities after the conquest. In The Edges of the Roman World. Edited by Marko A. Janković, Vladimir D. Mihajlović and Staša Babić. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, pp. 219–31. [Google Scholar]

- Eck, Werner, and Andreas Pangerl. 2005. Neue Militärdiplome für die mauretanischen Provinzen. Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 153: 188–94. [Google Scholar]

- Eck, Werner, and Andreas Pangerl. 2006a. Neue Diplome für die Auxiliartruppen in den moesischen Provinzen von Vespasian bis Hadrian. Dacia 50: 91–108. [Google Scholar]

- Eck, Werner, and Andreas Pangerl. 2006b. Syria unter Domitian und Hadrian. Neue Diplome für die Auxiliartruppen der Provinz. Chiron 36: 204–47. [Google Scholar]

- Fears, J. Rufus. 1981. The Cult of Jupiter and Roman Imperial Ideology. In Aufstieg und Niedergang der Römischen Welt: Geschichte und Kultur Roms im Spiegel der Neueren Forschung II. Prinzipat. 17. Band. 1. Teilband. Religion (Heidentum: Römische Götterkulte, Orientalische Kulte in der Römischen Welt). Edited by Wolfgang Haase. Berlin: Walter De Gruyter, pp. 7–141. [Google Scholar]

- Geiger, Daniel. 2009. Turner in the Tropics. The Frontier Concept Revisited. Ph.D. dissertation, Universität Luzern, Lucerne, Switzerland, December. [Google Scholar]

- Gesztelyi, Tamás. 1981. Tellus-Terra Mater in der Zeit des Prinzipats. In Aufstieg und Niedergang der Römischen Welt: Geschichte und Kultur Roms im Spiegel der Neueren Forschung II. Prinzipat. 17. Band. 1. Teilband. Religion (Heidentum: Römische Götterkulte, Orientalische Kulte in der Römischen Welt). Edited by Wolfgang Haase. Berlin: Walter De Gruyter, pp. 429–56. [Google Scholar]

- Haley, Evan W. 1991. Migration and Economy in Roman Imperial Spain. Barcelona: Publicacions Universitat de Barcelona. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, Jonathan M. 2002. Hellenicity. Between Ethnicity and Culture. Chicago: Chicago University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Haynes, Ian. 2013. Blood of the Provinces. The Roman auxilia and the Making of Provincial Society from Augustus to the Severans. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hirt, Alfred Michael. 2010. Imperial Mines and Quarries in the Roman World. Organizational Aspects 27 BC—AD 235. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Holleran, Claire. 2016. Labour Mobility in the Roman World. A Case Study of Mines in Iberia. In Migration and Mobility in the Early Roman Empire. Edited by Luuk de Ligt and Laurens E. Tacoma. Leiden: Koninlijke Brill NV, pp. 95–137. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, Siân. 1997. The Archaeology of Ethnicity. Constructing Identities in the Past and Present. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, Barri, and David Mattingly. 2002. An Atlas of Roman Britain. Oxford: Oxbow Books. [Google Scholar]

- Kajanto, Iiro. 1981. Fortuna. In Aufstieg und Niedergang der Römischen Welt: Geschichte und Kultur Roms im Spiegel der Neueren Forschung II. Prinzipat. 17. Band. 1. Teilband. Religion (Heidentum: Römische Götterkulte, Orientalische Kulte in der Römischen Welt). Edited by Wolfgang Haase. Berlin: Walter De Gruyter, pp. 503–58. [Google Scholar]

- Katičić, Radoslav. 1962. Die illyrischen Personenamen in ihrem östlichen Vebreitungsgebiet. Živa antika 12: 95–120. [Google Scholar]

- Katičić, Radoslav. 1963. Das mitteldalmatische Namengebiet. Živa antika 12: 255–92. [Google Scholar]

- Katičić, Radoslav. 1965. Zur Frage der keltischen und pannonischen Namengebiete im römischen Dalmatien. Godišnjak 3: 53–76. [Google Scholar]

- Katičić, Radoslav. 1968. Die einheimische Namengebung von Ig. Godišnjak 6: 61–120. [Google Scholar]

- Katičić, Radoslav. 1976. Ancient Languages of the Balkans. The Hague: Mouton & Co., vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Katičić, Radoslav. 1980. Die Balkanprovinzen. In Die Sprachen im Römischen Reich der Kaiserzeit, Kolloquium vom 8. bis 10. April 1974. Edited by Günter Neumann and Jürgen Untermann. Köln: Rheinland-Verlag, pp. 103–20. [Google Scholar]

- Kolendo, Jerzy. 1989. Le culte de Jupiter Depulsor et les incursions des Barbares. In Aufstieg und Niedergang der Römischen Welt: Geschichte und Kultur Roms im Spiegel der Neueren Forschung. Teil II. Prinzipat. Band 18. 2. Teilband. Religion (Heidentum: Die religiösen Verhältnisse in den Provinzen [Forts.]). Edited by Wolfgang Haase. Berlin: Walter De Gruyter, pp. 1062–76. [Google Scholar]

- Krahe, Hans. 1929. Lexikon Altillyrischer Personennamen. Heidelberg: Carl Winter’s Universitätsbuchhandlung. [Google Scholar]

- Lamar, Howard Roberts, and Leonard Monteath Thompson, eds. 1981. The Frontier in History: North America and Southern Africa Compared. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lamont, Michèle, and Virág Molnár. 2002. The Study of Boundaries in the Social Sciences. Annual Review of Sociology 28: 167–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leguilloux, Martine. 2006. Les animaux et l’alimentation d’après la faune: les restes de l’alimentation carnée des fortins de Krokodilô et Maximianon. In La route de Myos Hormos. L’armée romaine dans le désert Oriental d’Égypte. Vol. 2 (FIFAO 48/2). Edited by Hélène Cuvigny. Le Caire: Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale, pp. 549–88. [Google Scholar]

- Marx, Christoph. 2003. Grenzfälle. Zu Geschichte und Potential des Frontierbegriffs. Saeculum 54: 123–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, Anton. 1957. Die Sprache der alten Illyrier. Band I. Einleitung. Wörterbuch der illyrischen Sprachreste. Wien: Rudolf M. Rohrer. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, Anton. 1959. Die Sprache der alten Illyrier. Bd. II. Etymologisches Wörterbuch des Illyrischen. Grammatik der illyrischen Sprache. Wien: Rudolf M. Rohrer. [Google Scholar]

- McInerney, Jeremy, ed. 2014. A Companion to Ethnicity in Ancient Mediterranean. Malden: Wiley Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, Elizabeth A. 2004. Legitimacy and Law in the Roman World. Tabulae in Roman Belief and Practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Milošević, Ante. 1998. Arheološka Topografija Cetine. Split: Muzej hrvatskih arheoloških spomenika. [Google Scholar]

- Mischke, Jürgen. 2015. Familiennamen im mittelalterlichen Basel. Kulturhistorische Studien zu ihrer Entstehung und zeitgenössischen Bedeutung. Basel: Schwabe. [Google Scholar]

- Mladenović, Dragana. Forthcoming. Roman Gold and Silver Mining in the Central Balkans and its Significance for the Roman State.

- Mrozek, Stanislaw. 1969. Die Arbeitsverhältnisse in den Goldbergwerken des römischen Dazien. In Gesellschaft und Recht im Griechisch-Römischen Altertum. Eine Aufsatzsammlung. Teil 2. Edited by Mihail N. Andreev, Johannes Irmscher, Elemér Polay and Witold Warkallo. Berlin: Akademie-Verlag, pp. 139–55. [Google Scholar]

- Mrozek, Stanislaw. 1977. Die Goldbergwerke im römischen Dazien. In Aufstieg und Niedergang der Römischen Welt. Geschichte und Kultur Roms im Spiegel der Neueren Forschung II. Prinzipat. 6. Band. Politische Geschichte (Provinzen und Randvölker: Lateinischer Donau-Balkanraum). Edited by Hildegard Temporini and Wolfgang Haase. Berlin: Walter De Gruyter, pp. 95–109. [Google Scholar]

- Nemeti, Sorin. 2004. Bindus-Neptunus and Ianus Geminus at Alburnus Maior (Dacia). Studia Historica. Historia Antiqua 22: 91–101. [Google Scholar]

- Nemeti, Irina, and Sorin Nemeti. 2010. The Barbarians within. Illyrian colonists in Roman Dacia. Studia Historica. Historia Antigua 28: 109–33. [Google Scholar]

- Noeske, Hans-Christoph. 1977. Studien zur Verwaltung und Bevölkerung der dakischen Goldbergwerke in Römischer Zeit. Bonner Jahrbücher 170: 271–415. [Google Scholar]

- Nünning, Ansgar, ed. 2005. Grundbegriffe der Kulturtheorie und Kulturwissenschaften. Stuttgart: Verlag J.B. Metzler. [Google Scholar]

- Oltean, Ioana A. 2007. Dacia. Landscape, Colonisation and Romanisation. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Oltean, Ioana A. 2009. Dacian ethnic identity and the Roman army. In The army and Frontiers of Rome. Papers offered to David J. Breeze on the Occasion of his Sixty-Fifth Birthday and his Retirement from Historic Scotland. (Journal of Roman Archaeology Supplement Series 74); Edited by William S. Hanson. Portsmouth R.I.: Journal of Roman Archaeology, pp. 91–101. [Google Scholar]

- Osterhammel, Jürgen. 1995. Kulturelle Grenzen in der Expansion Europas. Saeculum 46: 101–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osterhammel, Jürgen. 2014. The Transformation of the World. A Global History of the Nineteenth Century. Princeton CT: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Patsch, Carl. 1899. Archäologisch-epigraphische Untersuchungen zur Geschichte der römischen Provinz Dalmatien. Wissenschaftliche Mittheilungen aus Bosnien und der Hercegovina 6: 154–273. [Google Scholar]

- Peacock, David P. A., and Valerie A. Maxfield, eds. 1997. Mons Claudianus. Survey and Excavation. 1987–1993. Volume I. Topography & Quarries (FIFAO 37). Cairo: Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale. [Google Scholar]

- Perinić, Ljubica. 2017. The Nature and Origin of the Cult of Silvanus in the Roman Provinces of Dalmatia and Pannonia. Oxford: Archaeopress. [Google Scholar]

- Piso, Ioan. 2004. Gli Illiri ad Alburnus Maior. In Dal Danubio all’Adriatico. L’Illirico nell’età greca e romana. Edited by Gianpaolo Urso. Pisa: Edizioni ETS, pp. 271–307. [Google Scholar]

- Piso, Ioan. 2008. Les débuts de la province de Dacie. In Die römischen Provinzen. Begriff und Gründung. Edited by Ioan Piso. Cluj-Napoca: Mega Verlag, pp. 297–331. [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen, Mattias Borg, and Christian Lund. 2017. Reconfiguring Frontier Spaces. The Territorialization of Resource Control. World Development 101: 388–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reger, Gary. 2014. Ethnic Identities, Borderlands, and Hybridity. In A Companion to Ethnicity in Ancient Mediterranean. Edited by Jeremy McInerney. Malden: Wiley Blackwell, pp. 112–26. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro, Beatriz, Fernando Oelze, and Orlando Soares Lopes. 2017. A Narrative of Resistance: A Brief History of the Dandara Community, Brazil. In Displacement and the Humanities: Manifestos from the Ancient to the Present. Edited by Elena Isayev and Evan Jewell. Special Issue. New York: Humanities, Volume 6, p. 70. [Google Scholar]

- Rohrbough, Malcolm J. 1997. Days of Gold. The California Gold Rush and the American Nation. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ruscu, Dan. 2004. The supposed extermination of the Dacians: The literary tradition. In Roman Dacia. The Making of a Provincial Society. Journal of Roman Archaeology Supplement Series 56; Edited by William S. Hanson and Ian P. Haynes. Portsmouth: Journal of Roman Archaeology, pp. 75–85. [Google Scholar]

- Russu, Ioan I. 1957. Numele de localități ìn tăblițele cerate din Dacia. Cercetări de Lingvistică 2: 243–50. [Google Scholar]

- Russu, Ioan I. 1975. Inscripțiile Daciei Romane. Vol. I. Introducere istorică și epigrafică, diplomele militare, tăblițele cerate. Bucureşti: Editura Academiei Republicii socialiste Romania. [Google Scholar]

- Sanders, Jimy M. 2002. Ethnic Boundaries and Identity in Plural Societies. Annual Review of Sociology 28: 327–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sastre Prats, Inés. 2002. Onomástica y relaciones políticas en la epigrafía del. Conventus Asturum durante el Alto Imperio (Anejos de Archivo Español de Arqueología XXV). Madrid: Consejo superior de Investigaciones Científicas. [Google Scholar]

- Shipley, Graham. 2011. Pseudo-Skylax’s Periplous: The Circumnavigation of the Inhabited World. Text, Translation and Commentary. Exeter: Bristol Phoenix Press. [Google Scholar]

- Škegro, Ante. 2000. Bergbau der römischen Provinz Dalmatien. Godišnjak 29: 53–173. [Google Scholar]

- Škegro, Ante. 2006. The economy of Roman Dalmatia. In Dalmatia. Research in the Roman Province 1970–2001. Papers in honour of J.J. Wilkes. British Archaeological Reports International Series 1576; Edited by David Davison, Vince Gaffney and Emilio Martin. Oxford: Archaeopress, pp. 149–73. [Google Scholar]

- Solin, Heikki. 2003. Die griechischen Personennamen in Rom. Ein Namenbuch. Berlin: Walter De Gruyter, Vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Speidel, Michael Alexander. 2009. Traian: Bellicosissimus Princeps. In Michael Alexander Speidel. Heer und Herrschaft im Römischen Reich der Hohen Kaiserzeit (MAVORS XVI). Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag, pp. 121–65. [Google Scholar]

- Strobel, Karl. 2005/2007. Die Frage der rumänischen Ethnogenese. Kontinuität—Diskontinuität im unteren Donauraum in Antike und Frühmittelalter. Balkan-Archiv Neue Folge 30–32: 59–173. [Google Scholar]

- Strobel, Karl. 2010. Kaiser Traian. Eine Epoche der Weltgeschichte. Regensburg: Verlag Friedrich Pustet. [Google Scholar]

- Tarpin, Michel. 2002. Vici et Pagi dans l’Occident Romain. Rome: École Française de Rome. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Veen, Marijke. 1998. A life of luxury in the desert? The food and fodder supply to Mons Claudianus. Journal of Roman Archaeology 11: 101–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Nijf, Onno. 2010. Being Termessian. Local Knowledge and Identity Politics in a Pisidian City. In Local Knowledge and Microidentities in the Imperial Greek World. Edited by Tim Whitmarsh. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 163–88. [Google Scholar]

- Velasco Murillo, Dana. 2009. Urban Indians in a Silver City. Zacatecas, Mexico, 1546–1806. Ph.D. dissertation, University of California, Los Angeles, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkes, John J. 1965. ΣΠΛAΥΝOΝ—Splonum again. Acta Antiqua Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 13: 111–25. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkes, John J. 1969. Dalmatia. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul. [Google Scholar]

- Wissowa, Georg. 1912. Religion und Kultus der Römer. München: Verlag C.H. Beck. [Google Scholar]

- Woodard, Roger D. 2008. The Ancient Languages of Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Woytek, Bernhard. 2004a. Die Metalla-Prägungen des Kaisers Traian und seiner Nachfolger. Numismatische Zeitschrift 111: 35–68. [Google Scholar]

- Woytek, Bernhard. 2004b. Die Metalla-Prägungen des Kaisers Traian und seiner Nachfolger: Supplementum. Mitteilungen der Österreichischen Numismatischen Gesellschaft 44: 134–39. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | Mrozek (1969, pp. 141–42); Mrozek (1977, p. 99). Daicoviciu (1958, p. 260) has the Dalmatians being sent by Rome (“l’envoi par Rome”); Wilkes (1969, p. 173) has them “transported” to Alburnus Maior, the Nemetis (Nemeti and Nemeti 2010, p. 111) speak of “dislocation”. Other scholars are a bit more careful in describing the movement of communities from Dalmatia to Alburnus Maior. |

| 2 | During the period of expansion under emperor Augustus (27BCE–14CE) young men of a conquered people could be forced into newly created auxiliary units (often carrying the name of the people they were recruited from, e.g., ala I Asturum or cohors I Cantabrorum); these units often served distant from home. With the consolidation of territorial gains during much of the 1st c. CE, recruitment to auxiliary units shifted from these original sources of manpower to volunteers, conscripts, and substitutes (for conscripts) from within and beyond the garrison province, see Haynes (2013, pp. 95–102, 121–34). With the conquest of Dacia the ‘Augustan’ practice was seemingly revived, though some Dacians were dispersed in small groups to units in provinces distant from Dacia (see below). |

| 3 | Use of the concept ‘displacement’ in this essay follows the definition set out in the introduction to this Special Issue. The terms ‘relocation’ or ‘resettlement’ are used here to describe a spatial movement and change of permanent residence by individuals, by a group, or a community; the terms are understood to be neutral, i.e. to be free of any implication as to rationale or impetus for this movement. For the use of ‘identity’ as describing a sense of sameness shared by a collective or group to which individuals associate themselves, or are associated by others, see Barnard and Spencer (2002, p. 292); Nünning (2005, pp. 71–72), with further bibliography. The term ‘ethnic’, in this essay, is very narrowly defined as a category of ascriptions or designations in Latin or Greek used by Greco-Roman authors and Imperial authorities for groups or ‘peoples’ (Gk. ‘ethnē’, Lat. ‘nationes’) and which are adopted/adapted as self-descriptive names by groups. We do not know whether or not terms such as Dacian, Dalmatian, Illyrian, etc., reflect group descriptions in non-Greek/Latin languages at all. For a general discussion of ‘ethnicity’ as a concept in ancient history and archaeology, see Jones (1997); Hall (2002); various contributions in McInerney (2014). |

| 4 | |

| 5 | Lamar and Thompson (1981, pp. 3–13); Marx (2003, pp. 123–24); Osterhammel (2014, pp. 326–27); see also Osterhammel (1995, pp. 111–14). |

| 6 | Osterhammel (2014, pp. 328–29). For the use of ‘frontier’ as a concept to describe the grab for resource in the internal peripheries of the developing world, see Geiger (2009); Rasmussen and Lund (2017, pp. 390–93). |

| 7 | Alternatively, the term ‘borderland’ or ‘border’ could be employed; in its narrow sense, i.e., a zone connected with a border between two political entities, ‘borderland’ seems less applicable, whereas in the wider sense as a cipher for a ‘social space where cross-group interactions take place’ (Sanders 2002, p. 328) it is conceptually too vague to be of analytical use, because it excludes the sense of remoteness from settled and ordered society (Lamont and Molnár 2002, pp. 167–69; Reger 2014, pp. 115–16). |

| 8 | It is entirely possible that the conquered Dacians did not adopt the habit of setting up inscribed monuments which might also partly explain their absence from the textual record. |

| 9 | Northwestern Spain: Florus 2.33.59 f.; Germania: Hirt (2010, p. 334), with further bibliography; Britain: RIB 2: 2404.31–6. 61–2; Jones and Mattingly (2002, pp. 66–77). |

| 10 | An Ulpius Hermias, an imperial libertus, a former slave manumitted by Trajan, is attested at Ampelum, serving as procurator for the Dacian goldmines under Trajan or Hadrian; CIL 3: 1312 = ILS 1593 = IDR III/3, 366, with Noeske (1977, pp. 296, 347, AMP 1). For the mining administration at Ampelum: Hirt (2010, pp. 126–30, 149–52). |

| 11 | CIL 3: p. 921; according to X. Neugebauer, in the ‘Josephigrube’, St. Joseph mine, six tablets were found in 1791 “neben einem alten Mann, der sofort zu Staub zerfiel als man ihn anrührte”, next to the corpse of an old man who immediately crumbled to dust when touched. For an overview of inscribed monuments, see Ciongradi (2009). |

| 12 | |

| 13 | 8.6.2: Traianus victa Dacia ex toto orbe Romano infinitas eo copias hominum transtulerat ad agros et urbes colendas. |

| 14 | 8.6.2: Dacia enim diuturno bello Decibali viris fuerat exhausta. |

| 15 | See p. 2 with n. 1. |

| 16 | Plin. NH. 33.67; Stat. Silv. 4.7.14-15; also see 1.2.153 and 3.3.89–90.; Mart. 10.79. |

| 17 | For a survey, see Škegro (2000); Škegro (2006, pp. 149–52). Much of the data provided, though, hails from publication of surveyors and mining engineers of the Austro-Hungarian Empire in the late 19th century, detailing what they think are Roman vestiges. On this problematic complex, see (Mladenović forthcoming). |

| 18 | According to Hélène Cuvigny (1996, p. 145) the wages the miners at Alburnus Maior received, seems to be well above average pay for menial labour, an indication that specialist work such as mining was well rewarded. |

| 19 | |

| 20 | TC VI, CIL 3, p. 936.6 (p. 2215), l. 4: de Dasio Verzonis Pirusta ex kaviereti[o]. It is not quite clear whether the toponym Kavieretium/k(astellum) Aviereti(um) refers to a place in or near the mining district of Alburnus Maior or whether it needs to be sought in Dalmatia in the territory of the Pirustae, see Daicoviciu (1958, p. 263); Piso (2004, p. 293, n. 146); Ciongradi et al. (2008, p. 254, n. 35). Dasius, son of Verzo, is furthermore mentioned as party to a land sale or the exchange of a lump sum in TC XVII, CIL 3, p. 954, see Noeske (1977, p. 409); Piso (2004, p. 280 no. 71). |

| 21 | For ‘Illyrian’ names noted in this text and footnotes see the Appendix A. |

| 22 | The names of the witnesses were not appended in their own handwriting, but by the same scribe who wrote the main text next to the individual seals of the witnesses, see Th. Mommsen, at CIL 3, p. 922; Ciulei (1983, p. 14). |

| 23 | For Kartum (or k(astellum) Artum?), see Russu (1957, p. 245); Daicoviciu (1958, p. 263); Piso (2004, p. 272 n. 11). |

| 24 | For the ‘Illyrian’ names, see Appendix A. For the toponyms? Sclaietae and Marcinium, see Russu (1957, p. 248); Noeske (1977, pp. 277, 393); Piso (2004, p. 292), with further bibliography. Masurius and Messius might well be Latin names, but an Illyrian interpretation of their names has been suggested as well, see Alföldy (1969, pp. 98–99). |

| 25 | The text does not specify which council he was part of, but a small community such as Alburnus Maior could have had a council as well. Noeske (1977, p. 275); Piso (2004, p. 300). Councils and magistrates are attested for vici, small settlements, as well, see Tarpin (2002, pp. 261–82); if Masurius were a member of a municipal ordo decurionum one would expect a Latin gentilnomen and tria nomina. |

| 26 | Principes of Delmatae, see CIL 3:2776; of civitates, see princeps Desit(i)atum (1st half 2nd c. CE; Breza; ILJug 1582), princeps civitatis Docl(e)atium (ILJug 1853), pri[nceps civ(itatis)] Dinda[riorum] (mid/late 2nd c. CE; Skelani [Sreberenica]; ILJug 1544); of municipia (e.g., CIL 3:2774, mid/late 2nd c. CE, Danilo Gornje [Šibenik]) and of other communities, i.e., a princeps k(astelli) Salthua (2nd half 2nd c. CE?; Suntulija near Riječani [Nikšić]; ILJug 1853), a princ[eps] caste[lli] from the Upper Cetina valley (Milošević 1998, pp. 102–3), or a princeps of a hitherto unnamed municipium S[…]/mod. Pljevlja, which is thought to be within the territory of the Pirustae (2nd half 2nd c. CE; AE 2002: 1115 = 2005: 1183). Leaders of the Iapodes are known as praepositus (CIL 3: 14325), praepositus Iapodum (CIL 3: 14328), or praepositus et princeps (CIL 3: 14324, 1432) in inscribed votive monuments to Bundus Neptunus at Privilica near Bihać, see Džino (2014, pp. 224–25). |

| 27 | |

| 28 | CIL 3: 1322 (late 2nd c. CE). Splonum has not yet been located, but the prevailing suggestions see it either in the territory of the Sardeates (see below) or of the Pirustae, see Alföldy (1962); Alföldy (1965, p. 158, near Šipovo, BIH); Wilkes (1965, p. 123, Plevlja, MNE); Bojanovski (1988, p. 255) = Barrington Atlas Map 20 (Vrtoče near Drvar, BIH); see also Piso (2004, p. 300, n. 216). Delmata here probably means the province rather than the civitas or tribe of the same name, see Piso (2004, p. 300 n. 216). |

| 29 | Noeske (1977, pp. 342, 393). Patsch (1899, p. 265 n. 7) saw Aper as member of the civic elite at Splonum. Whether further Dalmatian settlers came or were brought in under Septimius Severus in order to renew gold mining operations is another issue, which is closely linked to the problem whether the mining district suffered from the Marcomannic Wars in the late 160s and early 170s or not. Noeske (1977, pp. 343, 369); Piso (2004, pp. 301–2) does not believe that the latest date attested on wax tablets (March 29, 167 CE) is a terminus post quem for a Marcomannic attack on Dacia, unlike Noeske (1977, pp. 336–37); Birley (1993, pp. 151, 252). |

| 30 | Two witnesses Planius Verzonis and Liccaius Epicadi seem to be named together with their places of origin, i.e., Sclaies /Scalaietae and Marcinium, respectivly. Daicoviciu (1958, pp. 263–64 n. 28), Russu (1975, pp. 189–90), and Noeske (1977, p. 277) think these toponyms refer to localities in Dalmatia, indicating their origo or place of origin. Patsch (1899, p. 266) places them in the relative vicinity of Alburnus Maior. Piso (2004, p. 292, with further bibliography) suggests reading Sclaietis and Marciniesi as names of gentes or tribes. |

| 31 | |

| 32 | Funerary association: CIL 3, p. 924 ff.; loan receipt: CIL 3, pp. 930 ff.; loan contract: CIL 3, pp. 934–35; work contracts: CIL 3, pp. 933, 948–49; slave sale contracts: CIL 3, pp. 936 ff., 940 ff., 959ff.; house sale: CIL 3, pp. 944 ff.; deposit: CIL 3, p. 949; loan association: CIL 3, pp. 950–51. |

| 33 | TC VIII tab. 1 r l.3, CIL 3 pp. 944–45. (6 May 159 CE). Further evidence: a writ on dissolution of a funeral association was posted in Alburnus Maior ad statio Resculi (TC I l.2, CIL 3, p. 924 [9 February 167 CE]); a receipt details payment at Deusara (TC II tab. 3 r l.2, CIL 3, pp. 931–32 [20 June 162 CE]); a further slave sale contract is concluded in in the civilian settlement (cannabae) adjacent to the legionary camp of the XIIIth Gemina at Apulum/Alba Iulia ( TC VII tab. 2 r l.19, CIL 3, pp. 940–41. [16 May 142 CE]); a second slave sale contract is concluded at the same site: TC XXV tab. 2 r l.17, CIL 3, p. 959 (4 October 140 CE). A contract for work in the gold mines was concluded at Immenosum Maius: TC X l.11, CIL 3, p. 948 (19 May 164 CE). |

| 34 | |

| 35 | |

| 36 | |

| 37 | |

| 38 | |

| 39 | |

| 40 | |

| 41 | AE 2008: 1166 (Panes Bizonis), 1167 (Dasas Liccai); Ciongradi et al. (2008); Ciongradi (2009, nos. 109, 119). |

| 42 | |

| 43 | Caes. B Gall. 5.1; Livy 45.26.13; Strabo 7.5.3; Vell. Pat. 2.115.4; Plin. HN. 3.139-14; Ptol. Geog. 2.16.5.; App. Ill. 4.16. Alföldy (1963, pp. 190–91); Alföldy (1965, pp. 56–59); Bojanovski (1988, pp. 51–52, 90–91); Džino (2014, p. 223). |

| 44 | Alföldy (1965, pp. 59, 176) assumed that in the early Principate their territory was broken up into the smaller territories (civitates) which is why Pliny makes no mention of the Pirustae but notes the civitates of the Scirtones (Skirtari), the Ceraunii, and the Siculotae instead (HN. 3.143). |

| 45 | |

| 46 | |

| 47 | Sarnade: It. Ant. 269.3; Sarute: Tab. Peut.; Alföldy (1965, p. 53, near Pecka); Wilkes (1969, p. 170, west of Jajce), followed by Piso (2004, p. 294); Ardevan (2004, pp. 594–95). |

| 48 | Ps-Skylax 23–24; Shipley (2011, pp. 2–3, for date); Alföldy (1965, p. 99); Wilkes (1969, pp. 3, 5); Ardevan (2004, p. 594); Piso (2004, p. 295). |

| 49 | ILJug 3: 2775; Baridustae: Ardevan (2004, p. 593); Piso (2004, p. 293); Ciongradi (2009, p. 16); contra Wilkes (1969, pp. 184, 244). |

| 50 | |

| 51 | |

| 52 | |

| 53 | In Roman funerary or votive inscriptions, the origin or origo of a person is usually provided if he/she is not from the settlement where his/her tombstone or altar is erected. If the inscription only provides the name of a kastellum or vicus of the deceased, we may presume that the place is located relatively close by and within the confines of the same civitas (an overarching territorial body and community which included other settlements). If the person in question hails from outside a civitas (or colonia or municipium), a geographical or ethnic determinant (e.g., Delmata, Dacus, Breucus, Pirusta) is often provided in addition to, or instead of, the name of the settlement. A comparative sample is provided by inscriptions from Northwestern Spain and Portugal, where members of civitates/tribes in the Northwest move to distant mining districts and have their origins indicated on the funerary stones, see Haley (1991); Sastre Prats (2002); Holleran (2016). |

| 54 | The altars dedicated by three soldiers, all beneficiarii consularis, are produced and the letters carved with a bit more finesse than the other votives, revealing the military’s social status and wealth. By contrast, the altars dedicated by civilians are less elaborately executed, see Dészpa (2012, pp. 28–29), with the catalogue in Ciongradi (2009) for individual altars. |

| 55 | The resulting interpretations are associative and, at best, offer a flavour of the hopes and anxieties individuals and communities shared and required the support of divine beings for. |

| 56 | AE 1990: 844 (Batonianus); AE 2003: 1498 (Dasius Sta(–) [qui et?] Durius); AE 2003: 1509 (Surio Sumeletis). On Terra Mater, see Gesztelyi (1981, pp. 447–48); Dušanić (1999, pp. 132–33); Piso (2004, p. 296). |

| 57 | Piso (2004, p. 296, with n. 175). Aeracura: AE 1990: 841; W.A. Roscher, s.v. ‘Aeracura’, in: LexMyth 1/1, col. 85-86; Wissowa (1912, p. 313); Dušanić (1999, p. 132). Soranus: AE 1990: 832; Wissowa (1912, p. 238); G. Wissowa, s.v. ‘Soranus pater’ in: LexMyth 4: col. 1215–16; Dušanić (1999, p. 132). |

| 58 | AE 1990: 830 (Nasidius Primus); AE 2003:1507 (Valerius Niconis and Plator). Sorin Nemeti (2004) made the suggestion that behind Neptunus there is perhaps a Dalmatian god of water springs, Bindus or Bindus-Neptunus. |

| 59 | Maelantonius: AE 1990: 831; Naos/n: AE 1990: 839. |

| 60 | Asclepius: AE 2003: 1493 (M. Ul(pius) Cle(mens?)); Asclepius Augustus: Ciongradi (2009, p. no. 42, Fronto Plarentis); Wissowa (1912, pp. 306–7). |

| 61 | W.A. Roscher, s.v. ‘Planeten’, in: LexMyth 3/2: col. 2532–34. Diana: AE 1944: 21 = IDR 3.3: 387 (Panes Epicadi qui et Suttius), CIL 3: 7822 = IDR 3.3: 385 (Celsen(i)us Adiutor), AE 1965: 42 = IDR 3.3: 386 (Dassius). Apollo Pirunenus: AE 2003: 1502 (Macrianus Surionis), for Pirunenus, see Piso (2004, pp. 297–98). Apollo: AE 1960: 236 = IDR 3.3: 384 (Panes N[o?]setis), AE 2003: 1456 (Plator Implai), CIL 3: 7821 = IDR 3.3: 383 (Implaius Linsantis), AE 2003: 1495 (Verso Dasantis qui et Veidavius). |

| 62 | |

| 63 | Liber Pater: IDR 3.3: 396 (Atrius Maximi); CIL 3: 7826 = IDR 3.3: 397 (?); AE 2003: 1506 (Suttis Panentis f.); Liber et Libera: AE 2003: 1497 (Beucus Dasantis). On function, see Wissowa (1912, pp. 297–304); Dušanić (1999, p. 132); Piso (2004, p. 296, with fn. 175). Sidus: AE 1990: 849 = AE 2003: 1510 (Aelius Quintus); on deity, see Dušanić (1999, p. 132); Piso (2004, p. 296, with fn. 179). |

| 64 | Mercurius: AE 1990: 829 (Nasidius Primus); AE 2003: 1479 (Plator Implei), 1485 (Verzo Platoris), 1494 (Beuc(us?) Sut(tinis?)); on Mercurius see Wissowa (1912, pp. 305–6); Combet-Farnoux (1981). |

| 65 | Whether the altar to Fortuna (AE 2003: 1492) must be interpreted in the same vein, is open to speculation, see Kajanto (1981). The veneration of Asclepius must be a stark reminder of the health risks involved in mining, see AE 2003: 1493 (M. Ulpius Cl[-]); Ciongradi (2009, p. 59, no. 42, Fronto Plarentis). |

| 66 | Wissowa (1912, pp. 247–52); Dušanić (1999, pp. 130–31); J. Scheid, s.v. ‘Diana’, in: Brill’s New Pauly, consulted online on 26. 03. 2018, http://dx.doi.org.liverpool.idm.oclc.org/10.1163/1574-9347_bnp_e316670. |

| 67 | Silvanus: AE 1960: 235 = IDR 3.3: 403 (Varro Scen[-], Aelius Be[-]); AE 2003: 1496 (Dexter and Martialis); CIL 3: 7827 = IDR 3.3: 402 (Pla[-] Baotius?); CIL 3: 12564 = IDR 3.3: 404 (Rufi(us) Sten[-]); IDR 3.3: 407. Silvanus Augustus sacer: IDR 3.3: 405 (Hermes Myrini). Silvanus Silvestris sacer: AE 1944: 19 = IDR 3.3; 406 ([-] Annai(?)ius); IDR 3.3: 405a (Varro Titi). Silvanus sacer: CIL 3: 7828 = IDR 3.3:408 (k(astellum) Ansi). Silvanus Domesticus: CIL 3: 7828 = IDR 3.3: 408 (Sameccus). On Silvanus, see Wissowa (1912, pp. 213–16); Dészpa (2012); Perinić (2017, pp. 1–15, with further bibliography). |

| 68 | AE 1990: 846 (Implaius Sumeletis); AE 2003: 1508 (Ael(ius) Mes[-]). H. Herter, F. Heichelheim, s.v. ‘Nymphai’, in: RE 17, col. 1581–99; Wolfgang Speyer, s.v. ‘Nymphen’, in: RAC 26, col. 1–30. |

| 69 | Iupiter Optimus Maximus: CIL 3: 1260 = IDR 3.3: 390 (M. Aur. Maximus, legulus); IDR 3.3: 391 (M. Aur. Su[pe]<r>atus und M. Aur. Supe[ri]anus); AE 2003: 1488 (Dasas Loni, collegi Sardiatensium); CIL 3: 7823 = IDR 3.3: 392 (Implaius Lisantis); AE 1990: 837 (C. Iucundius Verus, bf. cos.); AE 1990: 827 (Q. Marius Proculus, bf. cos); AE 1990: 828 (C. Calpurnius Priscinus, bf. cos.); AE 2003: 1499 (Panes Stagilis); AE 2003: 1481 (Platius); AE 1990: 843 (Tritius Gar[-]); CIL 3: 7825 = IDR 3.3: 393 (Ve(r)z(o) Pant(onis)); IDR 3.3: 395. Iupiter Depulsor: AE 2003: 1482 (Platius Turi). On Iupiter, see Fears (1981); Kolendo (1989). The altars to Iuno (AE 1990: 834, 838) may fulfil a function similar to Iupiter, see Wissowa (1912, pp. 181–90). Venus: AE 2003: 1483 (Beucus Daieci) |

| 70 | TC XX, CIL 3, p. 956: Dasas Loni qui et [-]); AE 2003: 1498; Dasius Sta(–) (qui et ?) Durius; TC VI, CIL 3, p. 939: Epicadus Plarentis qui et Mico; AE 1944: 21: Panes Epicadi qui et Suttius; CIL 3: 1270: Planius Baezi qui et Magister; TC X, CIL 3, p. 948; TC XI, CIL 3, p. 949: Titus Beusantis qui et Bradua; AE 2003: 1495: Verso Dasantis qui (et) Veidavius. |

| 71 | See OLD s.v. magister. |

| 72 | For example, at medieval Basel: Mischke (2015, p. 16). |

| 73 | The translation is dependent on the reading of the word ἐξεῖλον. |

| 74 | Scholia in Lucianum [ed. Rabe] 24.16; Ruscu (2004, p. 75 ff.); Strobel (2005/2007, p. 93); Strobel (2010, p. 283). |

| 75 | |

| 76 | Dana and Zăgreanu (2013, pp. 157–58). On the linguistic identification of Dacian names, see Dana (2014, pp. LXVII–LXXV) with further bibliography. |

| 77 | On settlement types and density in the Late Iron Age/La Têne and Roman period see Oltean (2007, pp. 210–11); Oltean (2009, p. 92). |

| 78 | |

| 79 | Dio 54.22.5; K. Dietz, in: Czysz et al. (1995, pp. 43–44). |

| 80 | This already appears to be the case during the Dacian Wars with Dacian tribal groups siding with Rome and being included in newly established units such as cohors I Ulpia Dacorum civium Romanorum in 104 (relocated to Syria, according to a military diploma from 22 March 129, see Eck and Pangerl (2006b, pp. 221–30, no. 4) and cohors II (Ulpia?) Dacorum in 101 CE (see diploma from 9/10 December 125/6 CE in Eck and Pangerl (2006a, pp. 102–4). We also find single Dacians assigned to units in disparate provinces such as Lower Germany, Britain, or Africa Proconsularis already before 106 CE, see Strobel (2010, p. 295). |

| 81 | |

| 82 | Dana (2003, p. 183). For some of these Dacians we know the units they were enrolled in: ala Apriana and cohors I Flavia Cilicia equitata at Mons Claudianus or ala Vocontiorum at Krokodilo. Dana (2003, p. 183, with n. 83). |

| 83 | Dana (2003, p. 183); lists with Dacians: O. Claud. II 402, 403, 404, 405; O. Claud. inv. 29, 392, 1076, 1209, 1239, 1412, 1693, 1792, 3027, 8362. Dana (2003, s.vv. Aptasa, Blaikisa, Dekibalos, Diengi, Diourpa, Diourdanos, Dotos, Dotouzi, Eithazi, Geithozi, I-/Eithiokalos, Natopor, Petipor, Thiais, Thiaper, Titila, Zouroblost(-)); O. Did. 64; |

| 84 | |

| 85 | l.3: read armatus instead of armatum, statione instead of stationi; l.4: read imperatoris instead of imperatore. |

| 86 | |

| 87 | |

| 88 | O. Krok. inv. 503; O. Ka. La. inv. 37; Dana (2003, p. 183); Dana and Matei-Popescu (2006, p. 201). Perhaps one might add a letter in Latin (O. Did. 417) found at the fort of Didymoi/Khashm el-Minayh, written by a Numosis in which he greets a Crescens as his compatriot (conterraneus). Dana (2014, p. 262 s.v. Numosis) thinks Numosis was perhaps a Dacian name (?). |

| 89 | ed. and trans. Cuvigny (2005, p. 167). |

| 90 | O. Krok. 98 |

| 91 | For further evidence of correspondence amongst Dacians, see O. Did. 392, 435, 439; O. Krok. inv. 610, see Dana (2003, p. 176 s.v. Dida, Diernais) |

| 92 | |

| 93 | |

| 94 | Kaigiza: O. Krok. 1 (AD 108 or earlier). Dida: O. Krok. 11/12 (AD 108), 24 (AD 109), 30 (AD 109), 36 (c. AD 109). Auizina: O. Krok 71 (c. AD 109). |

| 95 | O. Krok. 87. |

| 96 | See Cuvigny (2005, p. 203 s.v. ἱππεύc). |

| 97 | For ala or cohors in documentary evidence from the Eastern Desert, e.g., O. Krok. 6, 14, 87; for turma, e.g., O. Ber. passim (τύρμη); O. Claud. 177; O. Krok. 6, 14, 24, 25, 26, 28, 29, 30, 31, 33, 47, 74, 102; O. Claud. 177. For turma, centuria and ala/cohors in votive and funerary texts, see IGR I.5: 1247, 1249, 1250; I. Ko.Ko. 19, 77, 92, 133; I. Pan 48 |

| 98 | |

| 99 | Baths: Brun and Reddé (2006); Peacock and Maxfield (1997, pp. 118–34, 137–38). On shaving, see O. Claud 176. |

| 100 | Diurpaneus, who waged war against Domitian (Oros. 7.10.4; Jord. Get. 76, 78) is also a name attested in the ostraca of the Eastern Desert, see Dana (2014, p. 145), but remains far less popular. |

| 101 | |

| 102 | That the use of historical and mythological slave names is a symbolic expression of Roman dominance over the conquered and victory over an external threat, is suggested by names such as Arsaces, Pacorus, Mithridates, Tigranes, Tiridates, or Pharnaces, eastern kings, most notably of Parthia and Armenia, who posed or pose a direct threat to Roman rule, see Solin (2003, pp. 240–44); Dana (2007, p. 46). |

| 103 | In the case of a child named Decibal[us] recorded on a third century tombstone from Birdoswald (RIB 1920), Haynes (2013) has suggested that the name Decebalus, together with the Dacian falx sword (on falx see pp. 289–92), seems to have become almost a cultural relic or regimental tradition, rather than the young boy being the son of a Dacian recruit (p. 133). The idea of the ‘martial race’ in docile service to Rome certainly permeates the description of Batavi and Tungrians by Tacitus in his narration of the battle at Mons Graupius (Tac. Agr. 35.2) or of the Batavi in his account of German tribes (Tac. Germ. 29). |

| 104 | |

| 105 | For a full list, see (Piso 2004, pp. 274–90). |

© 2018 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hirt, A. Dalmatians and Dacians—Forms of Belonging and Displacement in the Roman Empire. Humanities 2019, 8, 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/h8010001

Hirt A. Dalmatians and Dacians—Forms of Belonging and Displacement in the Roman Empire. Humanities. 2019; 8(1):1. https://doi.org/10.3390/h8010001

Chicago/Turabian StyleHirt, Alfred. 2019. "Dalmatians and Dacians—Forms of Belonging and Displacement in the Roman Empire" Humanities 8, no. 1: 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/h8010001

APA StyleHirt, A. (2019). Dalmatians and Dacians—Forms of Belonging and Displacement in the Roman Empire. Humanities, 8(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/h8010001