Overlaying the imagery of cats and mice onto genocide, Art Spiegelman famously and controversially anthropomorphized the Holocaust in his groundbreaking graphic novel. These seemingly reductive images succeed in telling a nuanced story in

Maus (

Spiegelman 1986), because animal characters in comics and animation tradition had long served two divergent goals: anthropomorphic characters are sympathetic vehicles for viewer identification, but they are also often vectors for racist caricature. The use of animal stand-ins has a history as long as world literature itself, most notably in traditions of fable and myth. Be it the snake-in-the-garden in Judeo-Christian tradition, or the wolf from Aesop’s fables (dated to Ancient Greece), animals who act as humans participate in a long tradition of morality narratives. In this essay, I pair Ari Folman’s

Waltz With Bashir (

Folman et al. 2009), a film documenting the 1982 Sabra and Shatila Massacre of Palestinians, with Rutu Modan and Igal Sarna’s 2009 comics collaboration, “War Rabbit”, a much lesser known documentary piece about the 2009 military strikes on Gaza and contemporary Israeli life.

1 These two texts portray Palestinian suffering through metaphorical representations of animal victims of state violence, giving more direct narrative space to rabbits, dogs and horses than human Palestinian victims. The use of animal avatars is superficially sympathetic to victims, moralizing the unjustness of their suffering, but this same trope unselfconsciously exemplifies the dehumanizing logic of persecution.

In this essay, I refer to the animals depicted in Waltz with Bashir and “War Rabbit” as “avatars” for human suffering. In so doing, I am indebted to critical game theory, and the scholarship on video and computer simulations in particular, for their critique of the identification function of these animal characters. Unlike role-playing games, in which consumers act through an avatar, these two narrative texts portray animal avatars as subjects with limited agency. Yet the animal characters nonetheless function as avatars in the sense that they are meant to provide identification with and access to an experience significantly divergent from the viewers’ reality. This representational strategy fetishizes their suffering, grossly simplifies their thoughts and feelings, and casts them as mute figures unable to speak for themselves.

Representing human suffering through animal analogy can be a way to foster recognition and a way to approach unknowable experience with empathy. It is also a way to escape the ethical problems of direct representation. As Susan Sontag famously argues, photographic images all too often trivialize violence, rendering out individual circumstance into the aesthetics of pain (

Sontag 2004). However, as this attempt at empathy operates through estrangement, representing human victims as animals risks reinstating hierarchal difference and casting victims as voiceless others. Drawing on graphic narratives aimed at young adult readers in particular, Suzanne Keen argues that animal avatars for the real-life plight of persecuted individuals and communities build “fast tracks to narrative empathy”, helping readers to identify with human circumstances more quickly. Even as she argues that the animal faces in comics activate “readers’ neural systems for recognition of basic emotions”, Keen is skeptical that the reader empathy cultivated for animal characters translates to increased empathy with real-world human victims (

Keen 2011, p. 137). Keen suggests that achieving the empathy required to “make a voluntary leap to the group targeted for compassion”, is particularly uncertain given young-adult readers’ cognitive and emotional maturity.

To state the obvious, identifying victims with animals eerily echoes dehumanizing persecutory rhetoric. Additionally, some animals are more sympathetic (often those that are pets) than others, following cultural associations. Keen astutely observes that the empathy animal avatars inspire is an empathy that easily plays into stereotypes and biases (p. 146). For these reasons Keen observes, “When it comes to evoking readers’ empathy in tales that employ animal figures, then, the representation of particular animals can rarely be a neutral matter. Household pets, farmyard animals, jungle dwellers, birds and sea creatures are already part of a literary tradition that dictates which figures will be sympathetic and which ones will automatically evoke antipathy” (p. 138).

Comics’ scholar Michael Chaney has likewise explored associations between animal metaphors and racist mythology in a reading of graphic novels that feature human characters who partially transform into animals: “talking animals, humans that become animal and humans that interact with magical, humanoid animals” (

Chaney 2011, p. 131). Animal avatars bear with them both cultural associations (i.e., the lazy tortoise) and racist overtones as certain races and nationalities are despairingly likened to particular animal species. Echoing Keen’s observation that all animals do not signify in the same ways, Chaney observes, “as the apotheosis of otherness, the animal is also a racial signifier” (p. 139). Thus, the rabbit metaphor in Modan’s comic conjures a stereotype of uncontrolled reproduction, while the dog metaphor in Folman’s film plays on images of dogs and horses as needing strong discipline (but servile when trained).

2 Obviously, these associations touch on relevant and troubling ideological aspects of the Israeli state’s treatment of Palestinian people.

Moreover, as

Christopher Pizzino (

2017) has recently explored, depicting animals as metaphors or “fables” for human beings can be read as itself an act of hubris and violence, in as much as doing so denies animals’ own realities. Recently, José Alaniz has suggested that comics’ focalization produces unique narratological capacity to represent animal experience as distinct from human experience (

Alaniz 2017). It is crucially important, then, that while

Waltz with Bashir and “War Rabbit” approach Palestinian plight through analogy to animal victims, neither simplistically renders them

as animals. In graphic texts that blur the distinction between animal and human, “the animal in such comics always functions as a mask or costume, beneath which lies the human, whose universality is reaffirmed and reified in the process” (

Chaney 2011, p. 135). This essay explores the status of universality and empathy in narratives in which animals and humans cannot speak to one another.

Haunting Images

Animals in “War Rabbit” and in Waltz with Bashir operate alternatively as an analogy for known human suffering and guilty fantasy of the part of Israeli protagonists. In “War Rabbit”, the illustrator, Rutu Modan, and writer, Igal Sarna deploy animals as a titular metonym for the Israeli–Palestinian conflict, comparing both sides to rabbits “driven underground”, in bomb-shelters and supply tunnels, respectively. Sarna and Modan, who appear as characters in their short comic, each encounter dead rabbits; as real and imagined victims, these helpless animals emphasize Israeli wrongdoing more than other allusions to Palestinian suffering in the comic. Similarly, Folman’s Waltz with Bashir begins with nightmares of dogs searching for Folman, the film’s former-soldier protagonist; the dogs are coming to take revenge on him for the dogs he killed as part of an Israeli military operation.

Rutu Modan is best known for her graphic novels

Exit Wounds (

Modan 2007) and

The Property (

Modan 2013). Modan’s writing has often taken inspiration from history and from Modan’s own life experiences, but the journalistic aspect of “War Rabbit”, on which she collaborated with popular Israeli non-fiction essayist, Igal Sarna, sets it apart in Modan’s oeuvre. Rather than casting a fictional set of characters in a realistic setting, as her graphic novels do in their treatment of terrorist bombings in Israel and Jewish–European ties after the Holocaust, Modan renders the stories of direct historical witnesses in “War Rabbit”. Unfortunately, “War Rabbit” has been largely ignored, with the vast majority of scholarly attention to Modan devoted to her book-length comics. Modan and Sarna visit an Israeli town near the Gaza border during an air raid. Structurally, “War Rabbit” alternates between representations of Modan and Sarna’s direct experience traveling to the border and imaginative renderings of the experiences of the town’s residents. Direct witnessing comes only from Israelis in “War Rabbit”. All but one of the scenes in the story seem to correspond to the point of view of an Israeli, specifically to Rutu Modan and Igal Sarna’s perspectives and to those of the family. Excluding the page depicting the Palestinian Nadam, which shows him operating a crane over Gaza—not directly present in or affected by events below—the story concerns itself with Israeli spaces and memories. To a degree, this bias is the unavoidable consequence of journalistic limitations; Modan and Sarna were unable to cross the border into Gaza and thus only had access to Israeli perspectives.

3 As Sarna laments, the Israeli state denied journalists access to Palestine during the Gaza War, over-representing Israeli suffering: “The tragedy is over there, but they’re not letting us in, so every cat that goes missing over here gets a bigger headline than a hundred of their dead do” (p. 2).

Ari Folman worked on

Waltz with Bashir for over two years, conducting interviews twice, filming live action footage, before animating the entire movie (

McCurdy 2016). Folman insists that the movie could only have been animated in the cut-outs process. Yoni Goodman, director of animation, elaborates, “We wanted to recreate the actual events, and to do more, to give the sense of anxiety, of fear, to really bring out the horrors of war through nightmares and hallucinations, and animation is really the best. The only way of telling the story as it should be told” (

McCurdy 2016). The documentary’s ostensible subject is the Sabra and Shatila massacre, as Israeli soldiers remember it.

Waltz emphasizes how other elements of the war, such as the stark contrast between civilian life and the front, obscure the massacre itself in individual and national Israeli memory. Tracing the memory of Israeli soldiers who witnessed the massacre indirectly,

Waltz with Bashir rarely depicts Palestinian victims on screen, but it would be overly simplistic to read this structural absence as disregard. Indeed,

Waltz is an agonized exploration of Israelis’ individual and collective guilt. As the filmmaker and subject, Folman’s lost memory becomes the central narrative problem of the film. While he interviews friends and fellow former soldiers, he begins to remember. However, as the film progresses, Folman meditates on the ways in which the process of taking in multiple perspectives, including interviews with officials during the war, very likely produces new memories as much as it recovers that which is lost. For these reasons,

Waltz with Bashir, not unlike “War Rabbit”, seems to invite a trauma-theory-oriented reading, tracing the circuitous path of repressed memory.

4 Rather than allowing the texts to direct their own reading in this way, this essay seeks to avoid investigation into the psyche of the traumatized Israeli soldier, and focuses instead on the limited ways each text represents Palestinians.

Animal victims recur in the film and frame the way it portrays human victims. In particular, while it is not until the film’s finale that we see the actual victims of the Sabra and Shatila massacre, a scene halfway through

Waltz pauses over the haunting dead eyes of horses,

Figure 1. The dead horse’s face is later echoed by that of a Palestinian girl found dead in the rubble after a massacre, both disturbingly swarmed with flies. This later image of the girl appears in the film’s final sequence, shortly before the animation gives way to documentary footage taken in the aftermath of the Sabra and Shatila massacre. By representing human suffering through voiceless animated animal stand-ins, which give way to direct recordings of the victims themselves, Folman’s film suggests that the human pain is unfathomably grave.

The image of the girl’s face,

Figure 2, echoes that of the horse seen earlier in the film. Part of the horror in this moment is that only a “head and hand” are visible in the rubble. The Israeli veteran who recounts this memory remarks on being struck by the resemblance between this dead girl and his own young child. It is significant and troubling that the girl’s eyes are closed, because this image is the only animated close-up of a victim’s face. In contrast to the image of the girl, the animated “camera” looks directly, in a very tight shot, into the eye of the dead horse, so closely as to show the soldier’s reflection in the moist eyeball. Looking into a living being’s eyes connotes self-recognition, a convention that is literalized in this animation.

Waltz with Bashir concludes with archival film footage after the massacre, producing an implicit, if unintended contrast between animal and human victims; for the first time, viewers are confronted with human victims not focalized through Israeli memory, victims who seem to confront the camera, seeking recognition.

This conclusion stands out all the more, because Palestinians are not very present at all in

Waltz with Bashir, nor in “War Rabbit”. While Folman’s film focuses on the Sabra and Shatila massacre, it is undoubtedly a film about the Israeli soldiers’ experience of it. Critiques of

Waltz have lamented the film’s reticence to center Palestinian experience and rightly observed that comparisons to the Holocaust function as an apology for Israeli state violence. Scholars such as Shira Stav remark on the way this choice privileges the Israeli perspective. Stav writes, “There is no point in asking why the Sabra and Shatila massacre echoes the memory of the Holocaust rather than events more relevant to the Palestinian experience. The mind that reflects is an Israeli mind, and memory can reflect nothing but what it contains: a Jewish story, an Israeli narrative” (

Stav 2012, p. 95). Stav is critical of Folman’s

Waltz with Bashir for failing to educate viewers (Israeli and international) about the Palestinian experience. This criticism applies equally well to Rutu Modan and Igal Sarna’s “War Rabbit”, which similarly speculates on the Palestinian experience through analogy to Jewish settlement life and the Holocaust.

The animation technique of

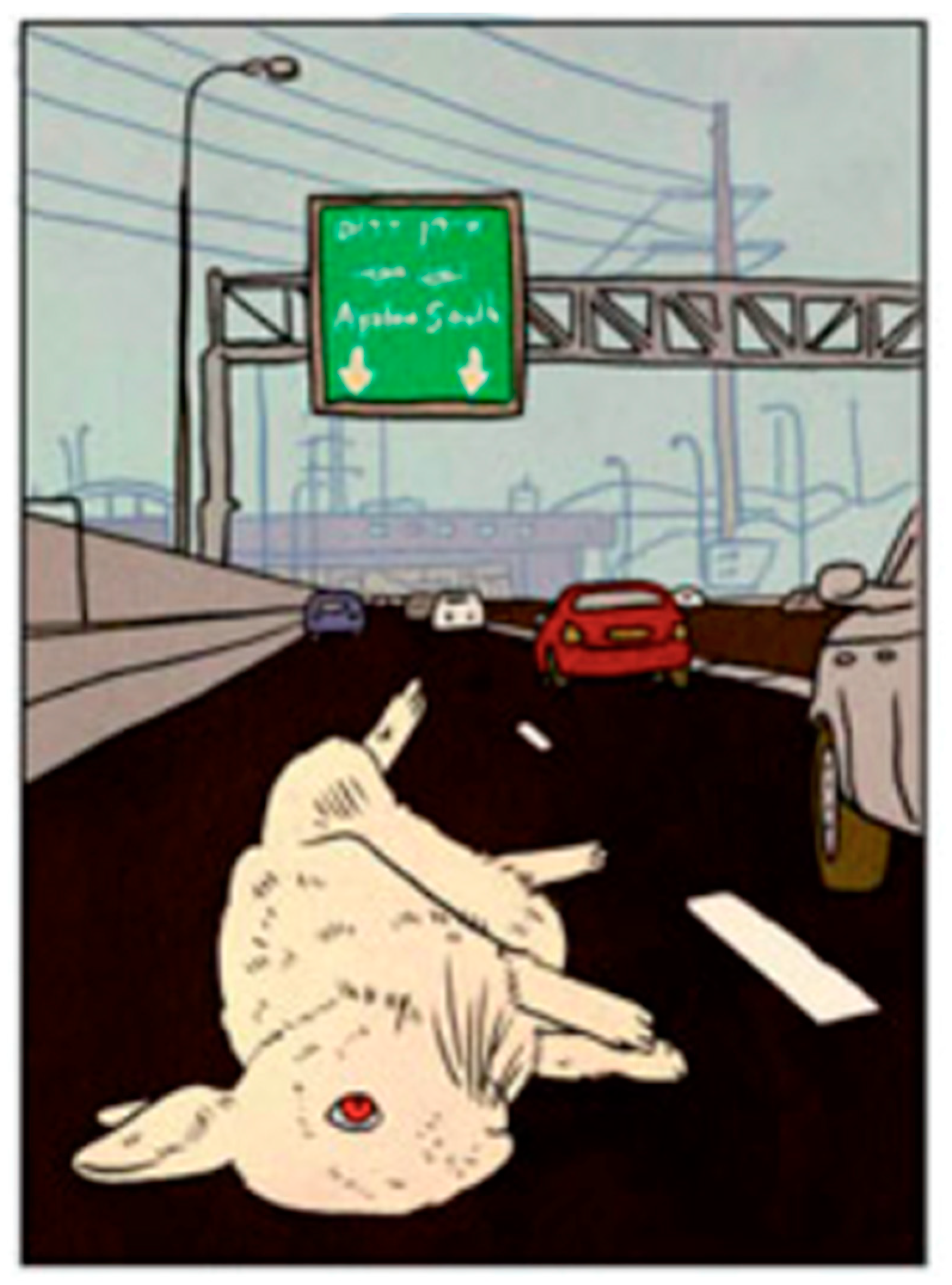

Waltz with Bashir and the panel structure in “War Rabbit” both portray the world in realistic, yet minimalist detail. Both graphic texts use their animal figures to join nightmarish imagination with reality. For instance, when Rutu imagines seeing a rabbit on the road in “War Rabbit”, the accompanying panel shows a larger than life rabbit in the middle of a highway,

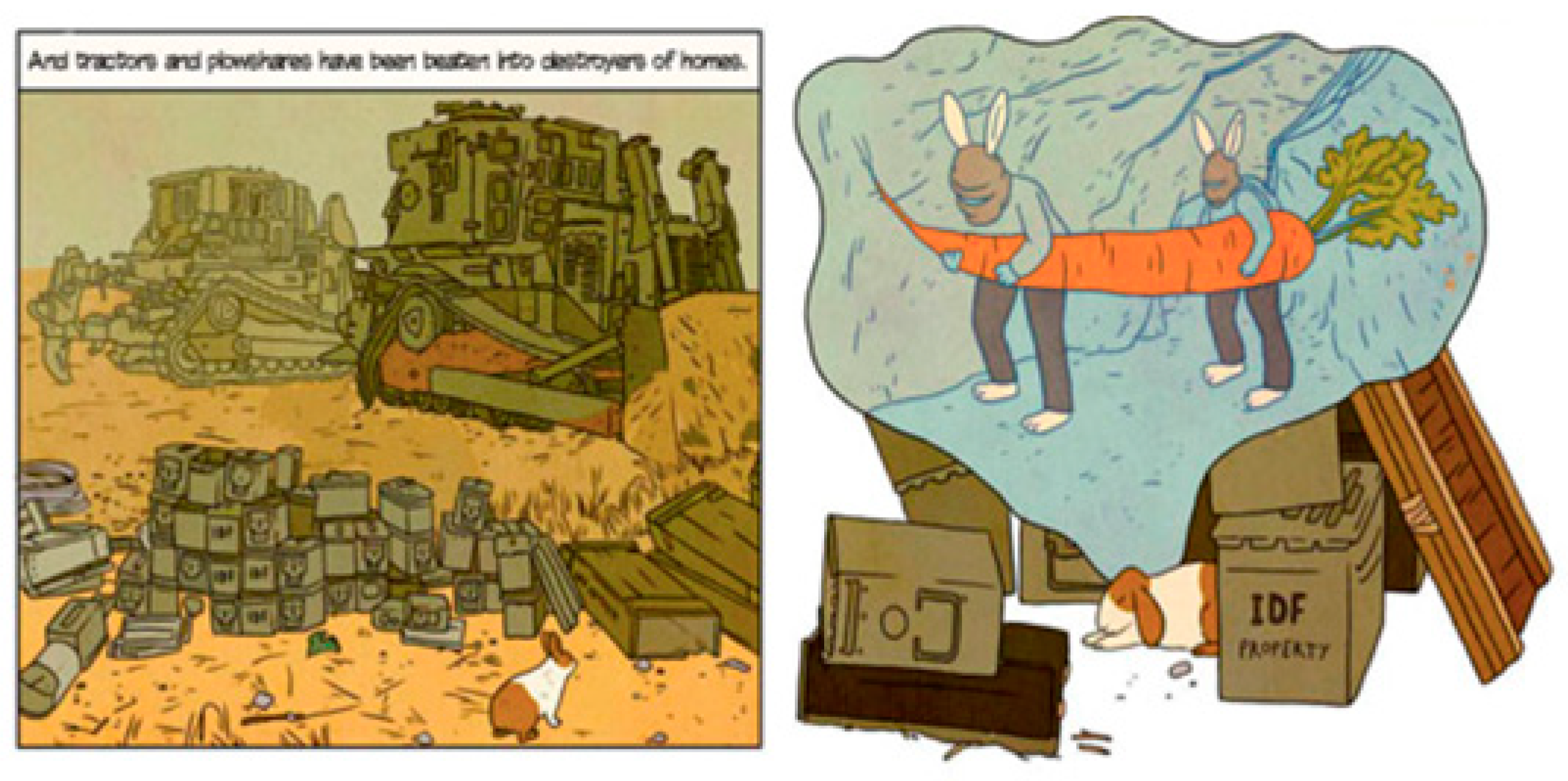

Figure 3. “War Rabbit” also shows anthropomorphized bunnies smuggling materials through a tunnel,

Figure 4. Modan’s style, heavily influenced by the visually flat, French ligne-clair comic tradition, favors compositions and detail that, like the cut-out animation process of

Waltz with Bashir, could easily be mistaken for rotoscoping (a tracing process).

5The visual style of

Waltz with Bashir reinforces the immediate/distant paradox of traumatic memory, producing an uncanny world where realistic figure-drawing meets exaggerated animation. In interviews, Folman insists that he could only have made

Waltz as an animated film. He says, “Doing this film in a different way was not an option. People keep asking why it was animated. And I never really understood why this is asked. It’s an animated film. End of story” (

Davidson 2016). One wagers that there is has been so much interest in Folman’s decision to animate his documentary film, at least in part, because it looks neither like most documentaries, nor frankly like most animations. To achieve

Waltz with Bashir, Folman and his team invented a new “cut-out” animation technique. Prior to animation, Folman and his crew filmed interviews, but they relied on the live-action footage only for reference, not for rotoscoping. The effect is a photorealistic visual style whose process insists upon subjective human filtering, as the filmed footage is reinterpreted by hand.

Sympathetic Identification and Its Limits

Much of the scholarly criticism of Folman’s film faults it for inadequately engaging the Palestinian experience and for not explicitly condemning Israelis for sanctioning it. This criticism asks that the film present a rational account of the Sabra and Shatila massacre, not the subjective memory of its creator and his acquaintances. While there is much less scholarly work on Modan and Sarna’s comic, the same criticisms could no doubt apply. Joseph A. Kraemer expresses this criticism in his discussion of the newsreel footage that closes

Waltz with Bashir: “The Palestinian Arabs of the film remain invisible figures, hardly pictured except in long shot, their voices and faces distant, obscure, and foreign. The funeral procession of women at the climax is shown as a mass of bobbing, veiled heads, their backs turned to the camera, faceless and moving as one mass” (

Kraemar 2015, p. 65). While I do not share Kraemar’s assumption that the cinematic alignment of the ‘camera-eye’ with the soldier is an endorsement of that vantage point, undeniably, the film makes little attempt to show the massacre from the perspective of its victims.

Structurally, Palestinian suffering looms in the background of both Waltz with Bashir and “War Rabbit”. Strikingly underrepresented in other ways, both “War Rabbit” and Waltz with Bashir represent Palestinian victims through metonymic animals: “War Rabbit” opens with the anecdote of a rabbit chased and scared to death by an IDF unit (the Israeli military, so named Israel "Defense" Forces) and Waltz with Bashir similarly begins with a soldier’s nightmare recollection of shooting dogs to silence them. That artists like Modan and Folman suggest that their audiences are more able to relate to rabbits and dogs than Palestinian humans speaks to the deep separation between the Western (including Israeli) and Palestinian communities. As Keen observes, “A reader resonating with empathetic feeling” with a dead animal, like Modan’s panic-stricken bunny or Folman’s rotting horse, “may not make a voluntary leap to the group targeted for compassion” (p. 146). This strategic symbolism highlights the misrecognition and misunderstandings negotiated under the sympathetic guise.

These animals constitute absolutely voiceless victims, devoid of language; sympathy with them means projecting one’s (human) experience and worldview onto their behavior, much as the children in “War Rabbit” project their life experience onto their pet rabbits, two pets that they consider “husband” and “wife”. When one rabbit gets lost, the children worry that the other misses his wife. This basic recognition, that victims of persecution have deep family ties, is often glaringly lacking in the treatment of the victims of human rights violations, who are routinely separated from one another by circumstance if not outright state policies. It is not only young children in “War Rabbit” who anthropomorphize the pet rabbits. When Yoram tells his teenage son that the Palestinian family also kept pet rabbits until poverty led them to “eat whatever we’ve got”, the son calls it “murder” to kill pet rabbits for food (p. 10). At this extreme, sympathy with animals takes precedence over recognition of human suffering.

“War Rabbit” explicitly applies the rabbit metaphor to Israelis and Palestinians alike, when Igal describes “human beings [driven] underground”, an apt description for settlement residents in bomb shelters as well as people whose livelihood depends upon smuggling goods via underground tunnels (

Modan and Sarna 2009b, p. 10). Yet, beginning with the very first page of the comic, the literal and metaphoric illustrations of rabbits much more strongly associate Palestinians with these animal victims. As in

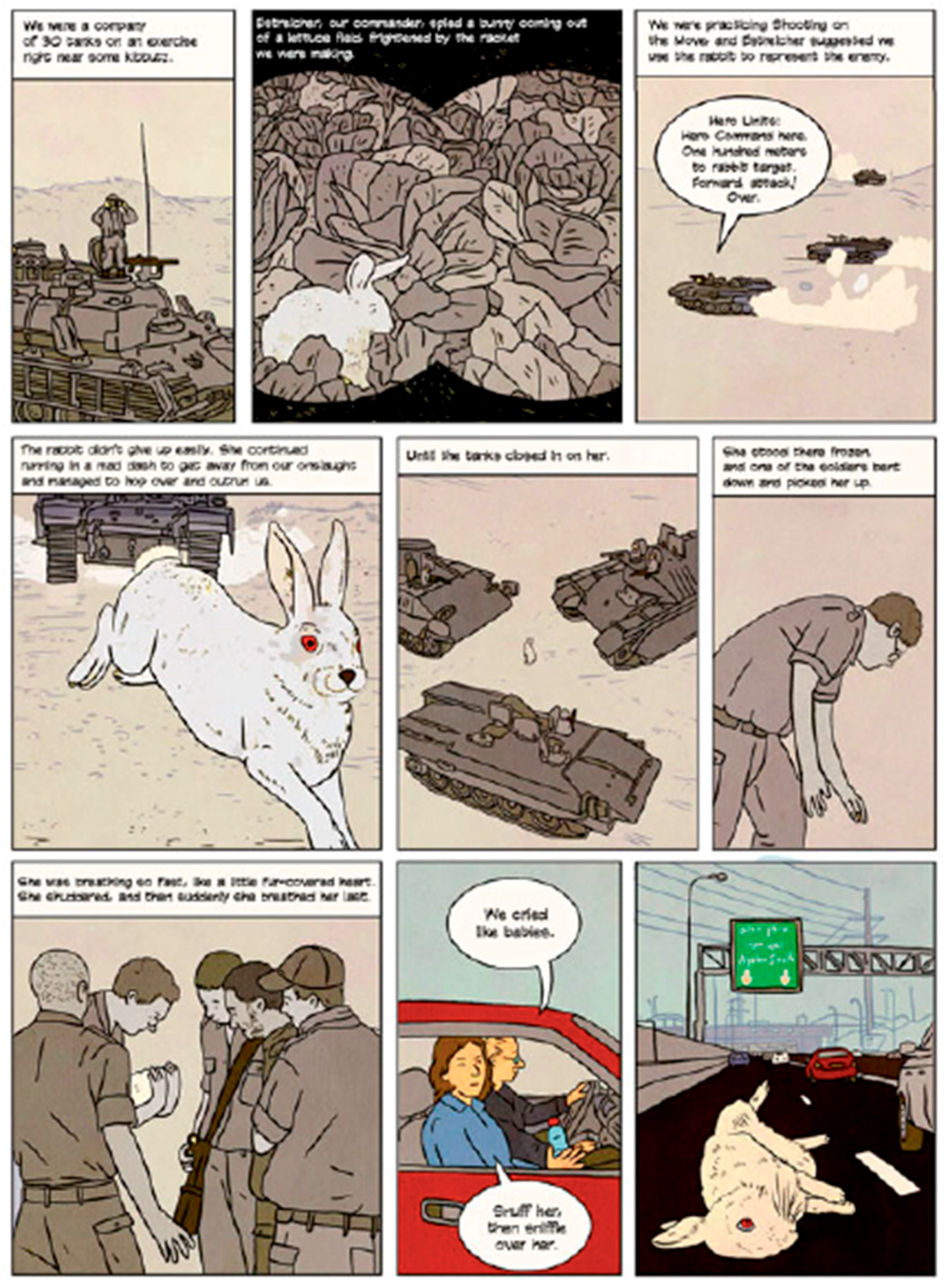

Waltz with Bashir, “War Rabbit” begins with a veteran Israeli soldier’s memory of killing a helpless animal. The speaker, later revealed to be Igal Sarna, recounts happening upon a rabbit in a lettuce patch during a training exercise: “We were practicing shooting on the move and [commander] Estreicher suggested we use the rabbit to represent the enemy” (

Modan and Sarna, 2009a, p. 1).

6 The attributed dialogue trivializes the exercise: “Hero Units: Hero Command here. One hundred meters to rabbit target”. The accompanying images emphasize the extreme imbalance between a single rabbit and three military tanks. Having trapped the rabbit, now “frozen” in fear, the soldiers pick up and cradle it as it dies in their arms. As if they were children unable to distinguish between games and reality, the soldiers are shocked and disturbed when the rabbit dies. Igal tells Rutu, “We cried like babies”, to which she responds, “Snuff her, then sniffle over her”.

“War Rabbit” encourages readers to dwell on this opening page for thematic meaning. Unlike the other twelve (of thirteen total) pages in “War Rabbit”, which portray a family in Netivot, and the conversations Modan and Sarna have about them, this very first page is only indirectly connected to the larger narrative in its depiction of nearby IDF tanks chasing a rabbit,

Figure 5. In addition to its distinct subject matter, this opening page stands apart from the rest of the comic with a visually muted style; as in two other places in the comic, sepia tones connote flashback, signaling the thematic importance of memory, but the first page features images far less color-saturated than any other. The page’s final image of a giant rabbit lying dead on a busy highway lane further emphasizes the rabbit motif by realistically depicting what can only be imagination. Its visual realism is compounded by the saturated color of the image, which links it to the adjacent panel—the only other fully colored panel on the page—which introduces Modan and Sarna as they discuss the memory.

This framing is a reminder to Western audiences that a story about Israeli settlement dwellers is also invariably a story about former and current soldiers, as the country conscripts military service. “War Rabbit” and Waltz with Bashir both suggest that Israelis’ military experience—compelled of each citizen in his or her youth—traumatizes these citizen-soldiers to the extent that they are unable to recognize Palestinian suffering, even as they are individually haunted by their own guilty consciences for it. On the surface, the two works sympathize with this traumatized Israeli perspective—even offering it as an apology for Israeli indifference to Palestinian suffering. Yet, read against the grain, this emphasis casts every Israeli, who in the majority of cases would be a current or former soldier, as someone who (could have) directly caused Palestinian suffering. As such, the texts’ attention to Israeli veterans’ trauma troubles the viewer sympathies it provokes. Moreover, “War Rabbit” places much emphasis on the callous attitudes of children too young for military deployment or the trauma it might involve, whose exposure to nationalist rhetoric hardens their hearts to Palestinian suffering.

If the animal victim in the opening sequence of “War Rabbit” connotes Palestinians as helpless victims, without place to run to and resources to resist, Waltz with Bashir lays its thematic groundwork through animal victims that signify threat. Waltz with Bashir portrays looking into the eyes of animal victims in two instances: first, a dreamed pack of dogs who metaphorically haunt an Israeli veteran, and secondly, in the herd of dying and dead horses discussed above. In the first instance, an angular black dog leaps onto the screen in the opening sequence of Waltz. It bounds forward snarling. The “camera” follows this single dog running through the streets. This animal metaphor is a mirror image to Modan’s rabbit episode. The dog is soon joined by a pack, which grows as the musical tempo increases. Like the rabbit, people cower and run, they freeze in place, a mother holds her child close, hoping the pack will pass them by. Yet, unlike the soldiers in “War Rabbit”, the dogs do not choose their target at random. They move in concert, pursuing a single target. The scene ends when the dogs gather below an apartment window, staring down a figure that peers out.

The sequence in

Waltz with Bashir is a nightmare, an imagination, (

Figure 6). Boaz Rein, friend of Ari Folman, recounts having this dream every night. Rein tells Folman (and viewers, by extension) that his dream always ends with the dogs demanding that Rein’s boss, “Give us Boaz Rein, or we’ll eat your customers. In one minute!” Rein knows exactly how many dogs appear in his dream—26—because that is the number of dogs he shot while searching villages for Palestinian “fugitives” during the Lebanon war. While rabbits and dogs leverage opposing semiotics of helplessness and menace, respectively, they both appear as military casualties in “War Rabbit” and

Waltz with Bashir. Dogs are killed, not by accident, but through necessity; the dogs would have barked an alarm and so needed to be neutralized. For Rein, these animal victims were an alternative to killing humans. As he recollects to Folman, his superiors ordered him to shoot: “They knew I couldn’t shoot a person. They told me: ‘Go ahead and shoot the dogs!’” Rein’s confession is followed by a reenactment sequence,

Figure 7. In it, Rein deliberates and reacts as if he were shooting a person. He takes aim at a dog, and a shot–reverse-shot structure suggests the dog meets his look with expressive eyes. The dog recoils when hit, whimpers and falls. Each of these details obscures the boundary between human and animal.

Why did his troop mates want him to shoot? One answer might be that military culture encourages a cavalier attitude to violence, but another explanation lies in what Rein does not say in his recollection. In the film Rein tells Folman that they were in the village(s) “to search for wanted Palestinians”, “fugitives” who would have evaded (or attacked) the IDF soldiers had the dogs been allowed to bark. It requires only a small leap of imagination to infer that they killed those Palestinians after finding them. Thus, Rein had to shoot the dogs not merely to harden his heart to violence, but also to directly participate in the human murder. Dogs are then a double signifier, both for acknowledged human victims of massacre and of forgotten victims. Forgotten because Rein’s nightly dream started only twenty years after the fact. Forgotten because even then, Palestinian deaths go unspoken.

Much as

Waltz includes images of dead horse and human faces that privilege looking at the animal victim, so too does it depict soldiers shooting both dogs and humans. Visually,

Waltz with Bashir resists proximity to human murder. Unlike the shot–reverse-shot sequence of close-ups used to depict the killing of dogs, one instance depicts the victims of the massacre being lined-up facing a wall and shot as though seen through binoculars, such that their bodies are distant and un-individualized.

7 Another sequence presents a young boy in the medium-distance gunned down by IDF soldiers, but not before his body and face disappear behind the missile he launches at the troops,

Figure 8. Undoubtedly, Folman would defend this repeated contrast by claiming an allegiance to honesty; he and the other former Israeli soldiers he interviews did not see the faces of Palestinian victims, let alone look into their eyes. That truth—that it is rare to look human suffering in the face and easier to empathize with animals—is all the more important for how unsettling.

Taken together, the two animal species function as analogies for Palestinian death as a consequence of Israel’s military policy, either as the inadvertent consequence of military routine or by strategic necessity. Waltz with Bashir portrays its animal victims as angry seekers of revenge, while “War Rabbit” casts them instead in a position of shocked defeat, but these interpretations reveal more about the psychology of the IDF veterans and their relationship to guilt than they reflect the accessible attitudes of the victims. Unlike the human, the animal is always without language; and, without mutual language, interspecies communication is all but impossible. Consequently, the indirect representation of Palestinian mortality through animal victims denies Palestinians the ability to communicate their own trauma. It denies them the ability to bridge the discursive divide to address Israelis, and worse yet, casts them as essentially mute.