Abstract

This paper reflects upon my experiences teaching and learning from displaced youth in Greece over a period of eight months in 2017. Following a brief examination of the current challenges in accessing formal education, I examine non-formal education initiatives, summarizing my work with two NGOs in Athens and Chios where I taught lessons in English on ancient Greek art, archaeology, history, and literature. In offering these lessons, my hope was to do more than simply improve students’ language skills or deposit information: I wanted to examine the past to reflect upon the present, exploring themes of migration, forced displacement, and human belonging. Moreover, I wanted to engage students in meaningful connection, to the past and to the present, to one and to others, as a means of building community in and beyond the classroom, at a time when many were feeling alienated and isolated. This paper, therefore, outlines the transformational, liberating learning that took place, citing ancient evidence of displacement and unpacking modern responses by those currently displaced.

But come now, tell me about your wanderings:describe the places, the people, and the cities you have seen.Which ones were wild and cruel, unwelcoming,and which were kind to visitors, respecting the gods?King Alcinous to Odysseus(Homer’s Odyssey, 8.571–576)1

“What was the role of the imagination when tales, spread by the roaming story-tellers, forged ideas of the world?”2 The Western world’s earliest known story-tellers, the Greeks, imagined a world both cruel and kind: Homer’s Odyssey gives us a snapshot of that world. I’ve read the Odyssey many times, on my own and with students, but only recently has this text come to resonate more profoundly with me on account of my own personal wanderings in Greece, where I worked with displaced Syrian youth. I wish to sing of the people and the places I have seen: how these experiences have compelled me to address the history of migration and forced displacement and to encourage other educators to bring this marginalized history to the forefront of teaching and learning, in ways that are both scholarly and sensitive.

1. Prologue: My Odyssey in Education

Two years ago, I finished a three-year teaching-stream post in the Department of Historical Studies at the University of Toronto Mississauga. Facing an uncertain future, I decided to take time to apply my love for teaching classics in a very different way: I spent most of 2017 teaching displaced youth in Greece, first on the island of Chios and then in Athens. In Chios I developed a series of lessons and workshops related to ancient history and classical art and archaeology. In Athens, I led small groups of youth on tours of local archaeological sites and museums.

My decision to work with displaced youth in Greece was inspired in part by the experiences of other academics teaching and working with marginalized groups in vulnerable contexts, both at home and abroad.3 In particular, I was stirred by the work of Richmond Eustis, a Fulbright Scholar who, in 2015, taught English to refugees at the University of Jordan using Homer’s Odyssey.4 Eustis recounts student responses to the text and how these responsive readings moved him by offering “a glimpse into another’s vision and experience of the world”. He also reflects on class discussions as a means of fostering personal connection: “Our lives could not be more different, and yet, strangely, I feel as though our fates are intertwined.” (Eustis 2015)

I too wanted to utilize my expertise in a more meaningful way, furthering my efforts to affect change in education and social justice.5 I was drawn to the migrant crisis in the Mediterranean for two reasons. First, I come from a family of migrants: my father and my grandparents on my mother’s side emigrated from Italy to Canada, but they moved as free people without fear of persecution. My family was lucky, and thus I have been lucky. Second, I have studied classics all of my adult life, and although my research has focused on the representation of ‘Others’ and theories of agency and identity (Trentin 2015b, 2016b), I had never seriously thought about migrants as an identity category. As a burgeoning field of interest, I was keen to explore this ancient theme in a modern context.6

What follows, then, is an account of my teaching experiences in Greece, with insights into: (1) the value of teaching ancient history to highlight shared stories of displacement in unfamiliar lands, (2) the role of education in bolstering the wellbeing of displaced youth during times of trauma and upheaval, and (3) the learning and liberty that can be gained through collective knowledge exchange. Based on my experiences, I will explore the pedagogy of border liberation, and transformative learning theory, drawing on the works of Paulo Freire, Henry Giroux, bell hooks, and Jack Mezirow, examining the ways in which a ‘problem-posing’, critically reflective approach to education can nurture biculturalism and cultural synthesis. Citing ancient evidence of displacement and unpacking modern responses by those currently displaced, I will outline the transformational, two-way learning that took place between teachers and students.

To be clear, what follows is an authentic, reflective piece about my personal and professional self-actualization, made possible by the relationships formed as a student among students. I was wholly ignorant to the dominant discourses on the pedagogies of oppression and liberation when I departed for Greece but returned acutely aware of these critical pedagogies in action (see below, Section 9. Learning from Displaced Youth in Greece).

2. Action for Education: Greece

In Europe, eighty percent of displaced people arrive by sea; from the east, most land in Greece via the Aegean islands of Lesbos, Chios and Samos, thereafter transferred to the mainland, either to Athens or Thessaloniki. Since 2015, over one million people have arrived on the Aegean islands, roughly half of whom under the age of eighteen.7

Among the numerous concerns raised by the migration crisis, the wellbeing of displaced children and youth is of utmost importance. Access to education is key to resilience-building, social integration and transcultural awareness, but the obstacles to full participation in formal education are considerable, especially for those between the ages of fifteen and eighteen, for whom education is not officially mandated.

Since the outset of the current migration crisis, the international community has recognized the value of education for displaced children. A number of international actors have been key driving forces in the right for formal education: UNESCO, UNICEF and the UNHCR. But perhaps the greatest efforts in the field of “creative engagement and [informal] education” has come from non-governmental organizations, or NGOs. In Greece, these include the Greek Council for Refugees, the Norwegian Refugee Council and Save the Children. NGOs on the ground have established ad hoc schools, providing safe and welcoming spaces, where children and youth can learn English and Greek, as well as essential social skills and school etiquette. Criticism of such schools has focused on the lack of professional teachers and formal evaluation of curricula, thus questioning the overall quality of education being delivered.8 To be sure, though the education provided by NGOs varies, they offer immediate support and sustained stability for displaced people in uncertain times.

In the spring of 2016, the Greek Ministry of Education, Research & Religious Affairs spearheaded the “Refugee Education Project” and officially assumed responsibility for “the formal education of refugees”: integrating refugee children under fifteen years of age in Greek schools and/or reception accommodation centres.9 All NGOs involved in education initiatives were invited to be certified by the Ministry, based on evaluation procedures prescribed by the Greek Ministry and Greek Higher Education Institutions. Still in its early stages, and facing significant obstacles in timing, structure and mobilization, the project has yet to reveal its full impact. Many children and youth are still waiting to go to school.

It is not my intent here to comment on the merits of a formal versus informal education. Emergency situations require immediate action; informal education provides access to knowledge and skills in lieu of formal education. I do not know the Greek school system well enough nor the particulars of its program of integration for refugees. But I do know about the teaching and learning that took place at a school run by a small NGO on the island of Chios: I will use this paper to summarize the academic, psychological, and social transformations that regular schooling, committed teachers, and engaging lessons can bring about by nurturing curiosity and excitement in the classroom.10

3. Teaching Displaced Youth in Chios

The island of Chios, seven kilometers west of the Turkish coast and port town of Cesme, has been a short and long-term ‘home’ to 131,021 displaced persons since 2015.11 The UNHCR records Chios island’s capacity at Vial camp—the sole official camp—as 1300, though it regularly overflows with nearly triple that number: in June of 2017, 3853 people lived in Vial camp.12 Of these individuals, 10 percent were minors.13

Amid the piteous conditions of camp life, there is hope, hospitality, and humanity enhanced by Greek solidarity groups and foreign-run NGOs.14 The UK based non-profit charity ‘Action for Education’ has taken on the challenge of providing free, non-formal education for the large numbers of displaced people inhabiting the island.15 Operating two schools (a primary and secondary school) and a youth centre, open seven days a week, and catering to children and youth between the ages of six and twenty-one years old, the schools provide more than an education: they are places of escape, offering safety and normalcy, beyond the camp.16 Run by volunteers from different professional backgrounds (teachers, but also artists, nurses, social workers, writers, etc.), the schools are alive with creativity and enthusiasm brought into the classrooms every single day: a curriculum that teaches English, but also includes, and is not limited to: archaeology workshops, computer and software skills training, cooking programs, German and Greek (and other languages) lessons, music and dance classes, science labs, studio art, and more.

This unofficial curriculum is positively Euro- and Anglo-centric; but it is also truly liberatory, striving to find a common ground for all. Lessons are taught in English, by native and non-native speakers, some of whom are certified ESL teachers, and most of whom come from Britain and Europe, though some––like me!––from further west.17 As the official international language of the EU and the UN, learning English is key for communication between displaced persons and foreign aid workers, thus students were eager to study English. But the methods of language instruction were not wholly traditional; staff were encouraged to test new and innovative teaching techniques, allowing greater freedom and flexibility in learning.18

During the five months I spent in Chios, I volunteered at the high-school teaching advanced English to (mostly Syrian) students between the ages of twelve and twenty-one. Together we read selections of Greek literature and myth (including parts of Homer’s Odyssey), exploring topics of war, migration and displacement. I also ran a series of workshops on ancient art (Greek pottery-painting and Roman mosaic-making), archaeology (tours of sites and museums), cultural heritage (lectures on Syria’s antiquities) and history (lessons on ancient Egypt, Greece, and Rome).19

I was surprised by the students’ interest in antiquity; their overwhelming positive response to a few introductory lessons on ancient history led to a series of themed activities that spanned over two months, with different activities geared to different age groups. By far, the most popular activities were those that involved hands-on construction or deconstruction: the art and archaeology workshops.

4. Ancient Art and Archaeology

“Awareness, creativeness, inter-disciplinarity, imagination.These engines drive mankind in formulating the “next step”.”—Segatto, Quantum Notes on Classic Places20

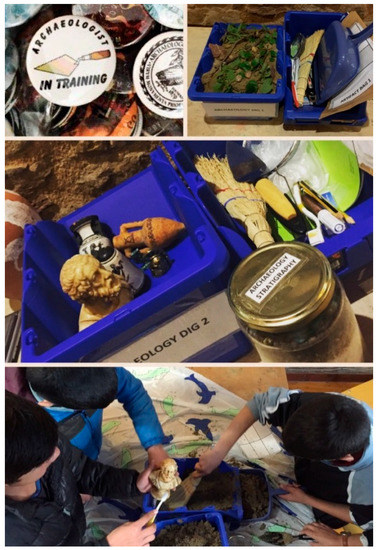

For the junior students (those between the ages of twelve to fifteen), the workshops on archaeology were most popular. The first activity organized was the creation and excavation of a layer-cake archaeological site.21 Students were split into two teams: each team was assigned a site and given edible artifacts to “bury”, recording the number of artifacts deposited in each layer, made of alternating cake and icing. The teams then switched sites and excavated, recording the number of artifacts discovered in each layer and describing key characteristics (shape, size, texture, etc.). Students learned the basic principles of stratigraphy and the importance of carefully “excavating” and describing discovered artifacts. They also loved that they got to eat cake, too! It was a messy activity, but well worth the mess.

The second activity organized was a sandbox dig (Figure 1).22 Box sites were constructed using beach sand and dirt with “real” artifacts: replicas of ancient Greek coins, pottery, and statuettes. Students were divided into teams to share the responsibilities of excavation: taking turns digging, sifting, measuring, recording, cleaning, and bagging all artifacts discovered. Students learned more about the techniques of excavation and the importance of handling artifacts with care. One student, while cleaning a miniature bust of Homer, dropped it, breaking part of it—the student was so distraught until I explained that archaeologists sometimes damage artifacts, too, when excavating or transporting them. Students liked this activity because they got to dig in the dirt and find cool stuff!

Figure 1.

Sandbox dig. Photo by author.

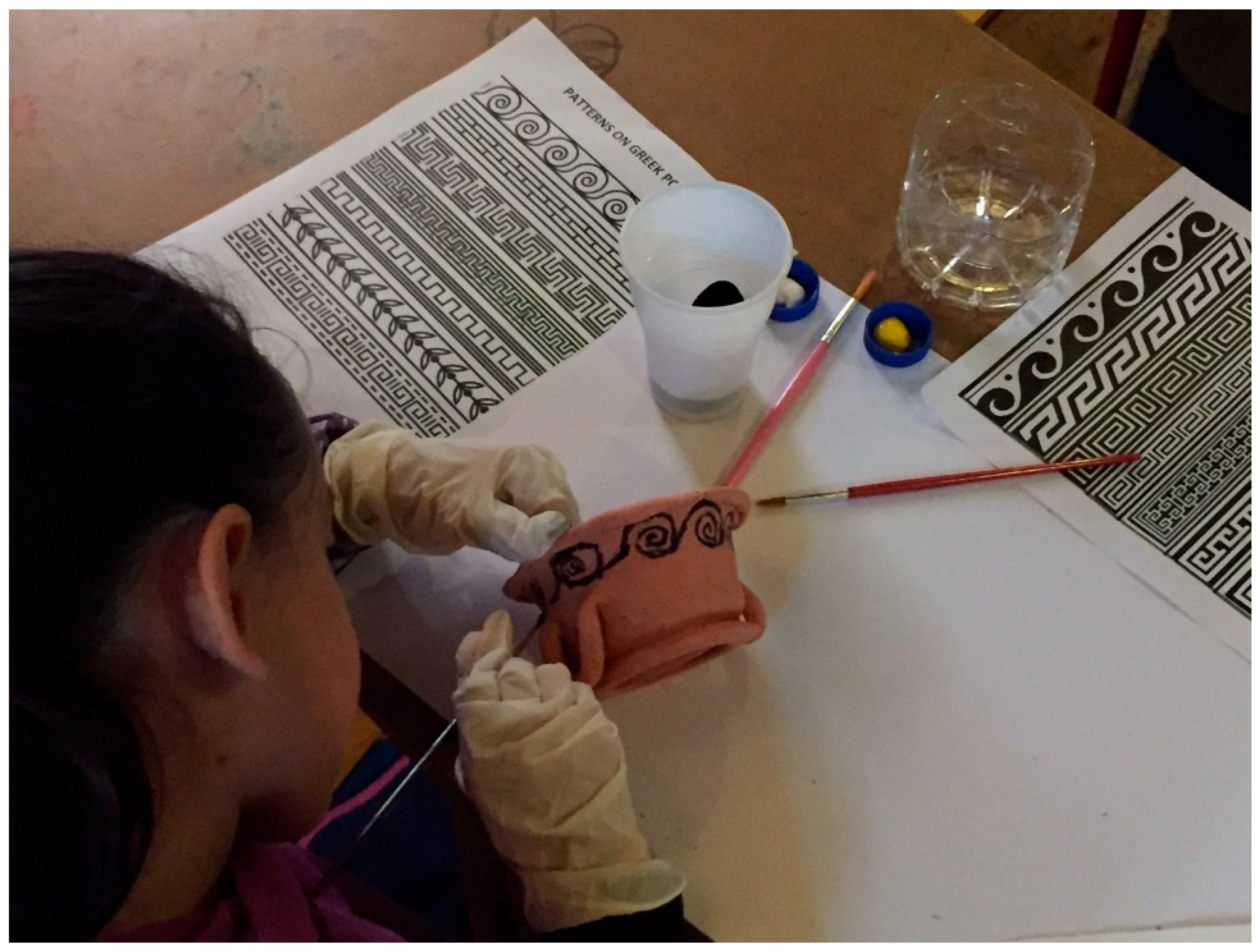

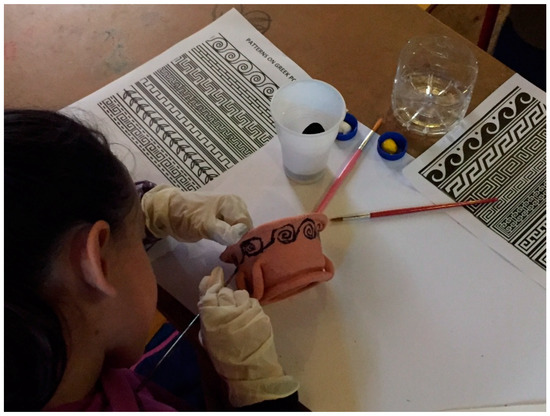

Also popular were the workshops on ancient art(-making). In a workshop on Greek pottery, students learned about the uses of different Greek pottery styles and practiced drawing pottery profiles as well as reconstructing pots from (replica Greek) pot sherds. They also made clay pots (small kraters) and painted them with geometric designs, according to ancient Greek pottery styles and techniques (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Greek vase-painting. Photo by author.

This workshop was paired with a class on Greek history, covering aspects of art, architecture, language and religion. Students were keen to learn the Greek alphabet and immediately tried to read signs in modern Greek. They were especially fascinated by my discussion of the Greeks’ migration out of Greece in the eighth century BCE and were eager to learn more about the site of Pithekoussai where artifacts recovered from tombs suggest maritime trade between Egypt, Greece, Italy and the east, including Syria.23

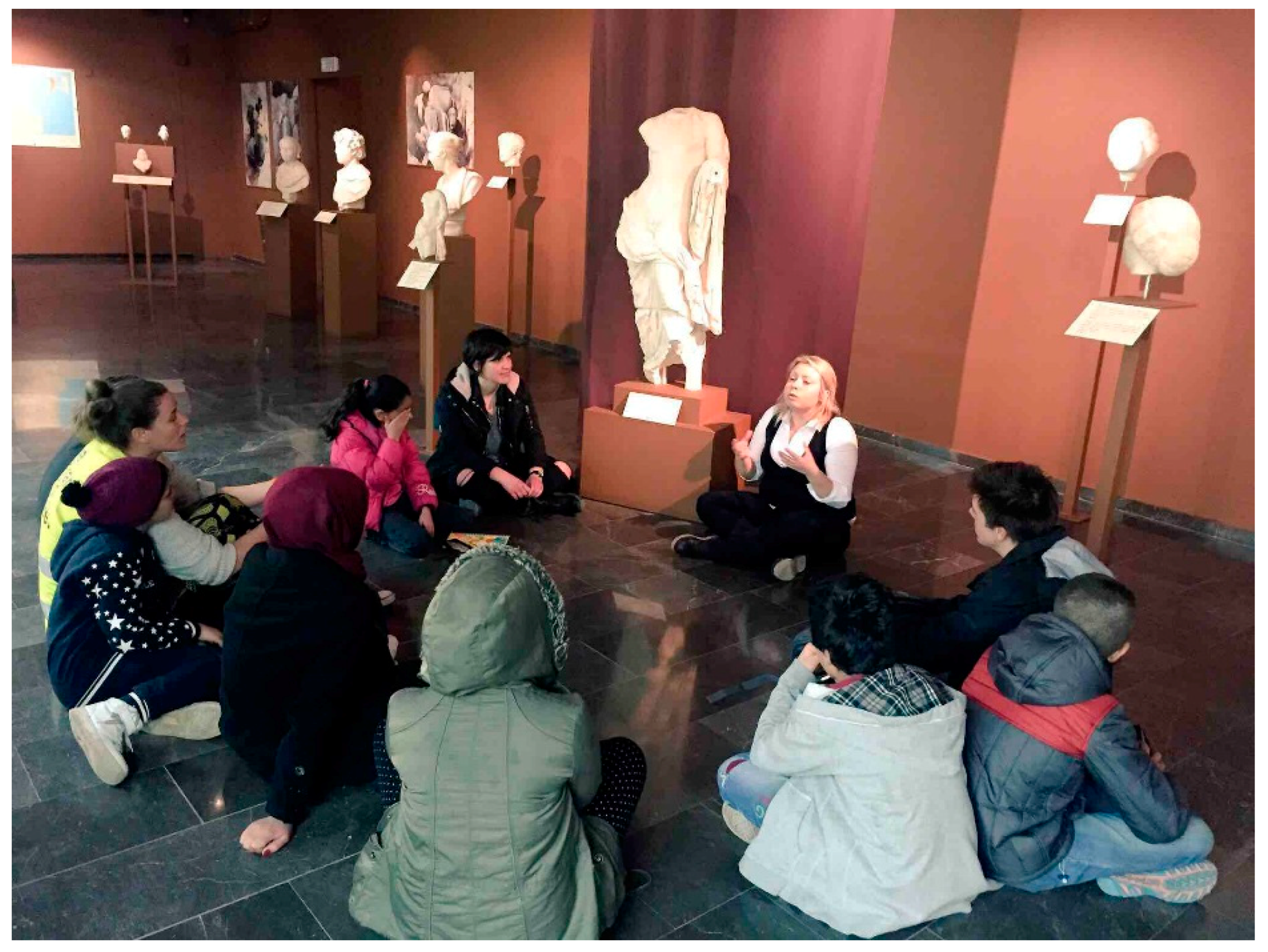

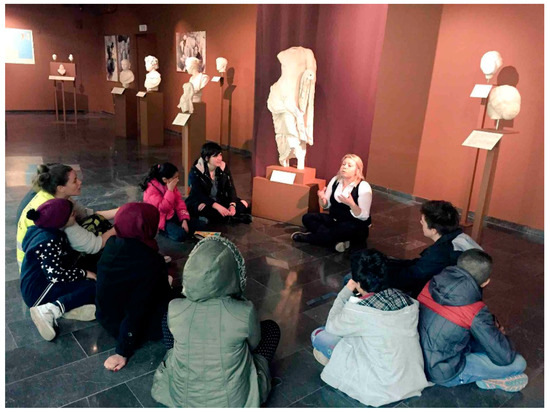

These lessons culminated with a field trip—the school’s and students’ first field trip!—to the Archaeological Museum of Chios, which has an excellent collection of ancient Greek (Chian) pottery. The Director of Antiquities in Chios arranged a guided tour of the museum’s collection provided by Dr. Maria Finfini, who encouraged students to really look at the artifacts, to ask questions, and to communicate their thoughts with her and with one another. The museum staff were delighted to have us and the students were jubilant to see real pots, and other artifacts (Figure 3).24

Figure 3.

Visiting the Chios Archaeological Museum. Photo by author.

5. Archaeology and Cultural Heritage

“Does the historian or the archaeologist—beyond the necessary preparation, competence, determination and method—need imagination to reconstruct the remains of those traces,the habits, the manufacturing, the thinking that is no longer present?”—Segatto, Quantum Notes on Classic Places25

The senior students (between the ages of sixteen to twenty-one) were involved in more analytical work, investigating cultural heritage and the history of archaeology at specific sites: Timgad in Algeria, Babylon in Iraq, Persepolis in Iran and Palmyra in Syria. Most students knew of these sites but had never been. Only one student, from Morocco, had been to the Roman site of Timgad and wrote a brief reflective piece about his visit, sharing this with the class and his peers as a means of visualizing the site.

An unplanned activity, arising from student interest, was a discussion about currency: students showcased their national currency, some of which honoured ancient buildings and sites, including the Roman Theatre at Bosra and the ruins of Palmyra, both in Syria. I took this opportunity to discuss the significance of commemorating historical monuments on money (a practice which dates back to the Romans). As a class we compared banknotes (Canadian, European, Syrian, etc.). What was represented and why?

During these discussions, students communicated concerns about the destruction of archaeological sites in their homelands, exposing varying degrees of emotional distress at the loss of their culture, their identity. When I showed students the controversial reconstructed Arch of Triumph from Palmyra, on display in London, they were bemused: why was it recreated? for whom? Having them research news articles about the reconstruction, they quoted Syria’s Director of Antiquities, Dr. Maamoun Abdulkarim, as saying “We have a common heritage. Our heritage is universal—it is not just for Syrian people”.26 This was a message raising cross-cultural awareness, and, more important for my students, it was a testimony to the value of sharing their culture and preserving their identity in the West.

After these sessions, my advanced English class, composed entirely of young Syrian men, took an interest in Syrian art and archaeology and wanted to know more. I dug up as much information as I could find: students read about Idrimi, the 3500 year old refugee whose inscribed statue is on display today at the British Museum;27 they explored the “Living History” of Syria through online videos from the 2016 Aga Khan Toronto exhibit, including works by contemporary Syrian artists in exile;28 and they examined digital images of artifacts-turned-artworks from a 2017 exhibit at the Museum of Classical Archaeology in Cambridge titled “Lost”, by Syrian-born artist Issam Kourbaj.29

The students had mixed responses to this material: they were surprised by the tale of Idrimi and ashamed that they had not known his story; they were fascinated by the ancient artifacts from their homeland and their modern adaptations but wondered why Canadians were so interested; and they were deeply disturbed by the plaster-dipped clothing belonging to migrants lost at sea. The pride in their country and its history, and the peril of their own journeys, were met with equal intensity.

These lessons gave students the opportunity to reflect on the complex history of their homeland: conquering peoples, forced displacement, the destruction of cultural heritage, and the connections between past and present in the construction of identity and reality. It also gave students a wider point of reference for understanding how the world beyond Greece was responding to the migration crisis, and how the voices of Syria remained alive, despite the country’s great losses. They became aware, too, of the importance of their voices and the power of sharing their stories.

In highlighting the work of Syrians abroad, students were (if only temporarily) optimistic about the preservation of their culture, and the liberation of their people. But they were also plagued by common concerns which came up again and again: We are different. We are strangers here. We do not belong. Europe does not want us. And the question asked by all, “How can we integrate without losing what it means to be Syrian?” A question asked by migrants and displaced people throughout history, and one I could only begin to tackle by introducing students to ancient Greek literature.

6. Ancient Greek Literature

“I’m led to believe that, once upon a time, as much as nowadays,those who move or are displaced from their land are led,in turn, to activate sooner or later an imaginationthat is beyond the necessities of migration and flight.”—Segatto, Quantum Notes on Classic Places30

With my advanced English students, I read selections of classical literature to unpack historical perspectives on ‘Otherness’ related to displacement, migration, refuge, and xenia.31 While I could have examined any number of texts, especially from the corpus of Greek tragedy ripe with tales of foreigners in the Greek world (e.g., Hecuba, Medea, the Danaids, etc.),32 I chose to examine a text about a (Greek) man’s long journey home, and the foreign places he visits and people he meets en route: Homer’s epic poem, the Odyssey.

The Odyssey recounts the Greek hero Odysseus’ ten-year voyage home to Ithaca in western Greece—via the Aegean and Mediterranean Seas—after having fought for ten years at Troy (modern Turkey). Along the way, Odysseus meets friends and foes; his encounters reveal a great deal about the construction of Greek identity, through association with and opposition to the ‘Other’. The story informs and warns readers of the complex cultural interactions that cannot be simply summarized as those between ‘civilized’ peoples, or hospitable hosts, and ‘uncivilized’ peoples, or hostile hosts.33

Fundamentally the Odyssey is a story about a migrant longing to return home and regain his identity. Odysseus’ journey is lengthy and risky, with a great many barriers to his freedom of movement: he is detoured to unknown lands, facing an uncertain welcome. Arriving in the land of the Phaeacians, Odysseus asks, “What is this country I have come to now? Are all the people wild and violent, or good, hospitable, and god-fearing?” (The Odyssey, 6.119–121). His story is one to which my students, and all displaced people, could intimately relate: foreigners at the mercy of strangers, uncertain if they would be welcome, hoping to forge a new life, longing for a home.

But the Odyssey is not just about Odysseus’ encounters with foreign people (‘Others’) in foreign lands, it is also a story about the ways in which those foreign people receive the stranger (Odysseus as ‘Other’). Odysseus is a man of military age: he is a lethal warrior. When Nausicaa and her slaves meet Odysseus, naked (except for a leafy branch used “to cover his manly parts”) and looking a wreck, all were “quite terrified” except Nausicaa who asks: “Why are you running from this man? Do you believe he is an enemy?” (The Odyssey, 6.129, 138 and 199–200) Is Odysseus to be feared? Can he be trusted?

My advanced English students were all young adult Muslim men: a critically vulnerable group who superficially ‘fit’ the profile of Islamic terrorists. President Donald Trump has expressed his fears that the “young, strong male refugees” entering the United States could be “the greatest Trojan horse of all time”: a reference to Odysseus’ master ruse which ultimately led to the destruction of Troy from within the city walls.34 Are refugees to be feared? Can they be trusted?

Reading selections of the Odyssey with my students provided the opportunity to survey the fears and hopes of strangers and hosts in the ancient and modern Greek worlds, examining the ancient roots of xenia and the modern sources of xenophobia. We read only from books six through nine, about the Phaeacians and the Cyclopses, a civil nation versus savage beasts, skipping sections that were particularly gruesome: bodily dismemberment, cannibalism, and bloody violence were topics that could rouse trauma, and my intention wasn’t to shock my students into understanding, but rather, to stress the limits and antonyms of xenia and the construction of the ‘Other’.35

Though we read only a small part of the Odyssey—it took a great deal of time to get through the text as students faced considerable challenges with the English translation—students were nevertheless able to connect the themes of migration, displacement and xenia with their own experiences, having traveled from Syria to Turkey to Greece. A few times this generated heated debate and emotional outbursts when students addressed abuse or neglect by organizations (e.g., the Greek or Turkish police, the EU asylum service, etc.).36 Other times our readings prompted sharing stories of comfort, hospitality, and generosity shown by strangers and ‘ordinary’ people (e.g., International volunteers, Greek solidarity groups and local citizens). Like Odysseus, these young men had met both friends and foes; these encounters not only shaped their view of the ‘Other’ but helped refine beliefs about the collective ‘Other’ and individual ‘Others’.37 And also like Odysseus—at once a hero, a warrior, a family-man, a trickster, a beggar and a migrant—these young men were negotiating their own layered identities.

The mysterious Homer, according to tradition, is thought to have been a blind bard from the island of Chios. As early as the sixth century BCE, a guild of bards were calling themselves the ‘Homeridae’, or progeny of Homer. Today, the island boasts of ‘Homer’s Rock’, a spot just north of Chios town in Vrontados, where Homer supposedly sang and taught.38 Towards the end of my time in Chios, I went in search of this rock with three of my former students: we sat and talked about Homer’s Odyssey, while gazing across the Aegean Sea to Turkey, a route traveled by all of us, but only one (me) as a free citizen.

After spending five months in Chios, I returned home to Toronto: a safe place that I knew and loved, where I was warmly welcomed by family and friends. I returned to Greece briefly in July, and then again in October to end the year, this time working in Athens.

7. Teaching Displaced Youth in Athens

Building on the archaeology and ancient history lessons and workshops I ran in Chios, I was keen to expand this initiative. Having visited Athens briefly in July, I chose to spend the last two months of 2017 there, volunteering with the Khora Community Centre, where I worked once again with migrants and displaced youth.

The Khora Centre, a humanitarian co-operative, is a one-stop shop for the displaced in Athens: it operates a freeshop (distributing clothes and hygiene products), a family space (with a kids’ play area), a communal kitchen (providing breakfast and lunch daily), a social café (with free wifi), an education space (for adult language classes), a library (for quiet study and reading) and numerous other resources and services (including legal, dental, and social assistance).39 Run by international volunteers with extensive field experience in Calais, Serbia, Lesbos, and Athens, and from a diverse range of cultural and political backgrounds and traditions, the Centre provides a positive model of collective co-working. It has hundreds of service users from Afghanistan, North Africa, Iran, Iraq and Syria: it is a truly multi-cultural space where foreigners from around the world converge and collaborate.

I worked with Khora volunteers in the education space to evaluate student English levels and coordinate classes, teachers and scheduling. In my free time, I led tours for interested students, some former students from Chios, some new students from Khora, to archaeological sites and museums. Here I witnessed true intersections and connections of people from diverse backgrounds, traditions, and statuses, sharing their histories.

8. Greek Art, Archaeology, and Ancient History

Although students had spent much time in and around Athens, few had visited the city’s ancient monuments or historical museums and thus had little knowledge of Athens’ rich history and legacy. It at first seemed that students weren’t interested in this legacy as it bore little connection to their own lives and realities. This would soon change.

Our first visit was to the National Archaeological Museum, home to many of Greece’s most famous artifacts. An interesting, though not unexpected, response from students surfaced: the female Muslim students were embarrassed by the male nudity of Archaic Greek statues and felt uncomfortable looking; the male students were amused (I suspect uncomfortably so) and looked at length.40 Viewing these artifacts raised questions about cultural customs and gender roles throughout time and place, from ancient Greece to modern Syria. Encouraging open, frank dialogue about these (dis)connections provided the opportunity to think critically about acceptable dress codes, gendered behaviour, and associated moral or ethical standards.41

Another site visited was the Acropolis Museum: students were intrigued by the use of colour on ancient art and dazzled by the architecture of the modern building against the ancient ruins of the Acropolis. Examining casts and originals of the Parthenon frieze, I discussed the history of the displaced marbles (the students had different opinions about the Ottomans), asking students to consider the debate of repatriation, using resources from the museum. What followed was an interesting conversation about the ownership and preservation of cultural heritage, including the destruction and reconstruction of historical monuments, the illicit trafficking of antiquities, and the display of looted artifacts in museums around the world.42 By and large, students were, in theory, keen to have artworks from their homelands displayed elsewhere if that meant protecting them, but the reality of viewing these works in foreign lands brought both delight and distress.

Following our visit to the Acropolis Museum, we toured the Acropolis itself. From the top of the city, I spoke briefly about the Greco-Persian wars, the sack of Athens in 480 BCE, and the (temporary) displacement of Athenian citizens. Students were surprised by this aspect of Greek history (they knew more about its history under Ottoman rule) and were intrigued by the layered interactions between Greeks and foreigners in Athens. Focusing on the Parthenon, students were interested in its transformation from a pagan temple, to a Christian church, to an Islamic mosque. Discussion turned to the role of religion and the conversion of places of worship, but this was short-lived, as a few students became uncomfortable and reluctant to engage, deeming any religious discussion connected to Islam haram. This was somewhat troubling for me: I wanted to encourage neutral dialogue but also remain sensitive to others’ feelings of unease (some feelings may not have been voiced), respecting conflicting religious beliefs.43

Other site visits included the Arch of Hadrian, the Roman Agora, the Athenian Agora, and the Temple of Olympian Zeus. Our site visits revealed points of connection and disconnection between “them” (the Greeks, or the Turks, or the Romans) and “us” (the Syrians). The Greeks were proud of their history and it was important for them to preserve it. The Athenians had experienced the ravages of war(s), with invasions that forced them to flee their city, at least temporarily. Athens’ most famous ancient monuments had been pillaged and damaged, but later repaired and reinstated as icons of Greece’s enduring history. Syrians too were proud of their culture and history, and hoped that it too would have a lasting legacy.

As the historical capital of Europe, Athens is the top tourist destination in Greece, with millions of international tourists visiting annually.44 In the centre of Athens people from around the world converge, negotiating national identities, cultural hierarchies, and personal relationships to the past. In Athens, you can clearly witness the Greek custom of xenia: strangers welcomed, sharing stories, shaping history.

9. Learning from Displaced Youth in Greece

Before I departed for Greece, a dear friend introduced me to the work of Paulo Freire and encouraged me to read his seminal book The Pedagogy of the Oppressed ahead of my travels.45 A year later, as I reflected on my teaching experiences, I would read Freire’s A Pedagogy of Freedom, Henry Giroux’s Border Crossings, and bell hooks’ Teaching to Transgress. As a white, Western teacher, I set off for Greece (unknowingly?) following centuries of colonial repression of the very people I would teach; I returned having learned a great deal about the challenges and possibilities of a truly revolutionary, transformative pedagogy and about education as a practice of freedom.46

This paper has laid out a model for teaching ancient history, archaeology, and classical literature as a means of highlighting shared stories; this type of dialogical, engaged pedagogy can bolster the wellbeing of displaced children and youth by allowing them a space to reflect and share, a place where their voices are heard, and their presence is recognized and respected. In a classroom where collective knowledge exchange happens naturally, learning becomes truly liberating. That liberation facilitates a transformation in the self.

In offering these lessons, my hope was to engage students in the discovery of history, theirs and others’ and our joint histories—to think critically about what it has meant to be displaced throughout history. In so doing, I wanted to problematize the distance and difference between “them” and “us”; on the flip side, I also wanted to emphasize diversity as an enriching element of cultural unity.47 Working with small groups of students encouraged the sharing of personal stories, exposing similar and different experiences, transforming our understanding of these monuments and texts, and, more importantly, each other.

This learning environment was intimate and intense. My advanced English class in Chios was by far the most challenging and rewarding class I have ever taught in my entire career. No day was the same and there was no such thing as a typical lesson plan or structure. I could prepare a lesson with the hope of getting through a specific text and covering key English grammar or vocabulary, but so many things outside of my control could foil these plans. Students could be (and were) prevented from attending class if there was a security issue within the camp, an emergency that required medical attention (self-harm), meetings with lawyers or psychologists, or an interview with the asylum service. Students could (and did) arrive late, exhausted, hungry, and/or distressed because of an incident (abuse, theft, violence) in or outside of the camp. Students could (and did) become irritable in class, either disengaging or instigating arguments. On any given day, I couldn’t predict the responses that students might have to a certain topic or text, nor could I prepare for the reactions that these responses might elicit in their peers.

And yet, they came. They arrived in (mostly) high spirits, enthusiastic and optimistic. They took care to listen to one another, to ask questions, to interpret or translate if the right word couldn’t be found by one. We shared stories, joked together, cried together. When one student became agitated or aggressive, another student would try to mollify him; if two students disagreed about something (usually a translation!), another student intervened. Never once did I feel threatened or unsafe. In fact, quite the opposite: I felt truly connected. I was called elhaj-je (Arabic for old aged! = matron, respected one) Lisa.

Our classroom was one defined by mutual respect; we worked together to create a connected learning space, though this was not without its ongoing challenges. It took some time for me to convince the students that I was interested in their responses, their stories, their lives. It took time for them to trust me and one another. Likewise, it took time for them to get used to our non-traditional language class which focused as much on context as it did content, on responses as much as readings, on individual stories as much as collective histories. As the weeks passed and as trust grew stronger, we shared more: listening and learning from one another, restoring hope in ourselves and the world.

This listening environment taught us all a valuable lesson: sharing personal stories is a sure way to establish mutual acceptance, tolerance and understanding. Knowing others helped us to know ourselves. By emphasizing our participation as individuals in an ongoing, collective discussion about e.g., migration and integration, human relations and human rights, and the impact of one(’s) voice, students were empowered with agency to act about the situation that their displacement landed them in. Rather than being passive ‘victims’, they had the awareness to challenge their reality and assume their freedom as humans.

Indeed, by emphasizing the value of each and every person and by encouraging thoughtful, open dialogue in the classroom, students experienced a level of liberation, despite being confined to the island. Evidence of this came in their increased confidence in the power of their voices and sharing their stories more widely. One student became particularly active: on the one-year anniversary of the EU-Turkey deal, he gave a speech in Chios town square during a public demonstration (16/03/2017); he also gave an interview with the Guardian about his journey to Greece (28/04/2017); and, once he had been transferred to the mainland, participated in a workshop on “The Mental Health of Refugees” in Athens (25/06/2017).48 Another student offered translation services and sewing lessons with the InterEuropean Human Aid Association in Thessaloniki; another student now acts as an Arabic cultural mediator in the Khora Centre in Athens. These students confronted the reality of their oppression, striving to rise above it. They did so not just to help themselves, but others too, working cooperatively with local and international communities.49

What struck me most about the youth I met was their resilience: despite the physical and psychological trauma they had endured, they came to school with open hearts and open minds, wanting to learn. There were no credits to be earned, no pass or fail grades. These were more than just students; I was more than a teacher; and the lessons we shared went far beyond art, archaeology, history, or literature. This was human connection that recognized our independence and interdependence through shared stories of courage, strength, vulnerability, and yearning.

10. Epilogue: My Nostos to Education

My pedagogical practice fundamentally shifted during my time in Greece: this was not a conscious development but rather one borne out of circumstance and context. In the traditional university classroom, I clung to the normative teacher-student hierarchy, asserting (as a young woman in the academy) my role as one who ‘knows’ and deposits my knowledge of the discipline to the unknowing student (the ‘banking’ system of education).

To be fair, despite this hierarchical environment, I have worked hard to develop undergraduate students’ skills in critical thinking and communication: examining literary texts (like Homer’s Odyssey) through the lens of characterization and ‘Otherness’, pressing students to consider constructions of identity in relation to themselves and the world in which we live (as privileged patricians attending a prestigious and internationally renowned institution of higher learning). I have always encouraged students to nurture their intellectual curiosity by asking questions, regardless of the answers that might (not) come (the ‘problem-posing’ system of education).

One could argue that forging authentic and meaningful personal connections (between students and teachers, or students and texts), in a lecture hall of 150 students, or even a seminar of 25 students, is near impossible. I don’t know this to be true or not, yet. I do know, however, that my experience teaching small groups of six to ten students in a non-formal educational environment, casting aside the teacher-student hierarchy, the constraints of a fixed curriculum, and the pressures of formal evaluation, yielded a more fluid, free learning environment, where students weren’t expected to memorize course content, but to interrogate it so as to access and assess their own realities.

I am brought back to Freire’s assertion that “looking at the past must be a means of understanding more clearly what and who we are so that we can more wisely build the future.”50 The stories of those students in Greece and the collective history of displaced peoples will be woven into the global history of displacement and human belonging, but it is up to us jointly to expose these stories, and other marginalized histories, to combat xenophobia and promote intercultural awareness and acceptance in our changing world.

For readers keen to use their skills and passion for the ancient world in a similar context, I hope that this paper has highlighted the possibilities of such endeavours, outlining some of the approaches to doing this work and striving to ensure it is carried out in an ethical and sensitive way.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Battle, Jacob. 2015. Nicholls Professor learns a little about himself halfway around the world. Houma Today. July 5. Available online: http://www.houmatoday.com/news/20160705/nicholls-professor-learns-a-little-about-himself-halfway-around-the-world (accessed on 7 February 2018).

- Beard, Mary. 2018. Mary Beard: A Don’s Life. Oxfam. The Times Literary Supplement. February 17. Available online: https://www.the-tls.co.uk/oxfam/ (accessed on 7 February 2018).

- Bond, Sarah. 2016. The Ethics of 3D-Printing Syria’s Cultural Heritage. Forbes. September 22. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/drsarahbond/2016/09/22/does-nycs-new-3d-printed-palmyra-arch-celebrate-syria-or-just-engage-in-digital-colonialism/ (accessed on 7 February 2018).

- Buchner, Giorgio. 1966. Pithekoussai. Oldest Greek Colony in the West. Expedition 5: 5–12. [Google Scholar]

- Dalal, Ayham. 2017. Uncovering Culture and Identity in Refugee Camps. In Displacement and the Humanities: Manifestos from the Ancient to the Present. Edited by Elena Isayev and Evan Jewell. Special issue, Humanities 6: 61. Available online: http://www.mdpi.com/2076-0787/6/3/61 (accessed on 7 February 2018).

- Doerries, Bryan. 2016. The Theatre of War. What Ancient Tragedies Can Teach Us Today. New York: Vintage. [Google Scholar]

- Eustis, Richmond. 2015. We’re all Refugees. Salon. February 12. Available online: https://www.salon.com/2015/12/02/were_all_refugees_what_teaching_displaced_syrians_taught_me_about_my_calling_and_my_country/ (accessed on 7 February 2018).

- Ferrari, Alessandro, and Sabrina Pastorelli. 2016. The Burqa Affair across Europe. Between Public and Private Space. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Freire, Paulo. 1970. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. Translated by Myra Bergman Ramos. London: Penguin Books. [Google Scholar]

- Freire, Paulo. 2001. Pedagogy of Freedom: Ethics, Democracy, and Civic Courage. Translated by Patrick Clarke. Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Freire, Paulo, and Antonio Faundez. 1989. Learning to Question. A Pedagogy of Liberation. New York: Continuum Books. [Google Scholar]

- Gabriel, Yiannis. 2003. Your Home, My Exile: Boundaries and ‘Otherness’ in Antiquity and Now. Organizational Studies 24: 619–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giroux, Henry. 2005. Border Crossings. Cultural Workers and the Politics of Education, 2nd ed. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Godderis, Rebecca. 2016. Trigger Warnings: Compassion is not Censorship. Radical Pedagogy 12: 130–38. [Google Scholar]

- Goff, Barbara. 2005. Classics and Colonialism. London: Duckworth. [Google Scholar]

- Greek Ministry of Education Research and Religious Affairs. 2017. Refugee Education Project. Available online: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/cmsdata/125422/refugee-education-project.pdf (accessed on 7 February 2018).

- Herman, Gabriel. 2002. Ritualized Friendship and the Greek City. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Homer. 2018. The Odyssey. Translated by Emily Wilson. London: W.W. Norton & Company. [Google Scholar]

- hooks, bell. 1994. Teaching to Transgress. Education as the Practice of Freedom. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- hooks, bell. 2004. Teaching Community. A Pedagogy of Hope. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Isayev, Elena. 2017. Xenia. Campus in Camps Collective Dictionary. Exeter: University of Exeter, Available online: http://www.campusincamps.ps/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/XENIA_CollectiveDictionary_CiC_download.pdf (accessed on 7 February 2018).

- Kostara, Effrosyni. 2016. Developing critical thinking in the education and training of adult educators through classical literature. Paper presented at the XII International Transformative Learning Conference–Engaging at the Intersections, Tacoma, WA, USA, October 20–23. [Google Scholar]

- Meineck, Peter, and David Konstan. 2014. Combat Trauma and the Ancient Greeks. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Mezirow, Jack. 2000. Learning as Transformation: Critical Perspectives on a Theory in Progress. San Francisco: Jossey Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Munawar, Nour. 2017. Reconstructing Cultural Heritage in Conflict Zones: Should Palmyra be Rebuilt? Journal of Archaeology 2: 33–48. [Google Scholar]

- Rabinowitz, Nancy. 2013. Teaching Greek Tragedy in Prisons. Classics Confidential. October 16. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8PstjDffC7Y (accessed on 7 February 2018).

- Rabinowitz, Nancy. 2014. Women and War in Tragedy. In Combat Trauma and the Ancient Greeks. Edited by Peter Meineck and David Konstan. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 185–206. [Google Scholar]

- Rabinowitz, Nancy, and Fiona McHardy. 2014. From Abortion to Pederasty. Addressing Difficult Topics in the Classics Classroom. Columbus: Ohio State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Refugee Rights Data Project. 2017a. An Island at Breaking Point. May. Available online: http://refugeerights.org.uk/wpcontent/uploads/2017/07/RRDP_AnIslandAtBreakingPoint.pdf (accessed on 7 February 2018).

- Refugee Rights Data Project. 2017b. The State of Refugees and Displaced People in Europe. August. Available online: http://refugeerights.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/RRDP_Findings_2016-17-2.pdf (accessed on 7 February 2018).

- Refugee Rights Data Project. 2017c. Top Five Facts. November. Available online: http://refugeerights.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/RRDP_Top5Facts.pdf (accessed on 7 February 2018).

- Rhodan, Maya. 2015. Are the Syrian Refugees all ‘Young, Strong Men’? Time. November 21. Available online: http://time.com/4122186/syrian-refugees-donald-trump-young-men/ (accessed on 7 February 2018).

- Rohde, Katharina. 2017. Collaborations on the Edge. In Displacement and the Humanities: Manifestos from the Ancient to the Present. Edited by Elena Isayev and Evan Jewell. Special issue, Humanities 6: 59. Available online: http://www.mdpi.com/2076-0787/6/3/59 (accessed on 7 February 2018).

- Segatto, Diego. 2017. Quantum Notes on Classic Places. In Displacement and the Humanities: Manifestos from the Ancient to the Present. Edited by Elena Isayev and Evan Jewell. Special issue, Humanities 6: 54. Available online: http://www.mdpi.com/2076-0787/6/3/54 (accessed on 7 February 2018).

- Skarvteit, Hanna-Lovise, and Katherine Goodnow. 2010. Changes in Museum Practice. New Media, Refugees, and Participation. New York: Berghahn Books. [Google Scholar]

- Skotheim, Mali. 2015. Classics through Bars. Eidolon. June 18. Available online: https://eidolon.pub/classics-through-bars-b4bf3ae6ef7a (accessed on 7 February 2018).

- Stewart, Roberta. 2015. Ancient Narratives and Modern War Stories: Reading Homer with Combat Veterans. Amphora 12: 1–3, 20–21. [Google Scholar]

- Strolonga, Polyxeni. 2014. Teaching Uncomfortable Subjects: When Religious Beliefs get in the Way. In From Abortion to Pederasty. Addressing Difficult Topics in the Classics Classroom. Edited by Nancy Rabinowitz and Fiona McHardy. Columbus: Ohio State University Press, pp. 107–18. [Google Scholar]

- Trentin, Lisa. 2014. Talking about Disability in the Classics Classroom. In From Abortion to Pederasty: Addressing Difficult Topics in the Classics Classroom. Edited by Nancy Rabinowitz and Fiona McHardy. Columbus: Ohio State University Press, pp. 54–71. [Google Scholar]

- Trentin, Lisa. 2015a. The body, physical difference and disability in ancient Greece. In Embedding Equity and Diversity in the Curriculum: A Classics Practitioner’s Guide. Edited by Susan Deacy. Scotland: The Higher Education Academy, Available online: https://www.heacademy.ac.uk/system/files/resources/eedc_classics_online.pdf (accessed on 7 February 2018).

- Trentin, Lisa. 2015b. The Hunchback in Hellenistic and Roman Art. London: Bloomsbury Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Trentin, Lisa. 2016a. A History of the Women’s Network of the Classical Association of Canada. Cloelia. October 11. Available online: https://medium.com/cloelia-wcc/a-history-of-the-womens-network-of-the-classical-association-of-canada-the-wn-executive-lisa-275bade71441 (accessed on 7 February 2018).

- Trentin, Lisa. 2016b. The ‘Other’ Romans: Deformed Bodies in the Visual Arts of Rome. In Disability in Antiquity. Edited by Christian Laes. London: Routledge, pp. 233–47. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, Lauren. 2016. Palmyra’s Arch of Triumph Recreated in London. BBC News. April 19. Available online: http://www.bbc.com/news/uk-36070721 (accessed on 7 February 2018).

- UNHCR. 2015. Chios Island Snapshot. December 31. Available online: https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/Daily_Arrival_Chios_31122015.pdf (accessed on 7 February 2018).

- UNHCR. 2016a. Profiling of Syrian Arrivals on the Greek Islands 2016. March. Available online: https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/SyriansMarchProfilingFactsheet.pdf (accessed on 7 February 2018).

- UNHCR. 2016b. Chios Island Snapshot. March 20. Available online: https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/Daily_Snapshot_Chios_20032016.pdf (accessed on 7 February 2018).

- UNHCR. 2017a. Europe Refugee Emergency Weekly Map. June 20. Available online: http://www.refworld.org/docid/595253924.html (accessed on 7 February 2018).

- UNHCR. 2017b. Global Trends. Forced Displacement in 2016. June 19. Available online: http://www.unhcr.org/5943e8a34.pdf (accessed on 7 February 2018).

- UNHCR. 2018. Greece: Sea Arrivals Dashboard—December 2017. January 5. Available online: https://data2.unhcr.org/en/documents/download/61492 (accessed on 7 February 2018).

- UNICEF. 2018. End of Year Report, 2017—Syria Crisis: 2017 Humanitarian Results. January 14. Available online: https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/UNICEF_Syria_Crisis_Situation_Report_2017_year_end_External.pdf (accessed on 7 February 2018).

- West, Martin. 1999. The Invention of Homer. The Classical Quarterly 49: 364–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, Jessica. 2016. Talking to Strangers (Inside): Teaching Latin in the Prison Classroom. Cloelia. December 13. Available online: https://medium.com/cloelia-wcc/talking-to-strangers-inside-teaching-latin-in-the-prison-classroom-559c44ff7c76 (accessed on 7 February 2018).

- Wright, Jessica. 2017. Latin Behind Bars. Teaching College Latin in an American Prison. Eidolon. January 16. Available online: https://eidolon.pub/latin-behind-bars-8ab9cfb14557 (accessed on 7 February 2018).

| 1 | This translation, and all to follow, from Homer (2018, trans. Wilson). |

| 2 | Segatto (2017, p. 3) in this volume. |

| 3 | In particular, the efforts of classicists working through trauma with prisoners (Rabinowitz 2013, 2014; Skotheim 2015; Wright 2016, 2017) and war veterans (Meineck and Konstan 2014; Stewart 2015; Doerries 2016) using ancient texts. See also the Ancient Greeks/Modern Lives: Poetry-Drama-Dialogue program organized by the Aquila Theatre from September 2011 to May 2012: www.ancientgreeksmodernlives.org. |

| 4 | Eustis (2015) and Battle (2015). See also the 2012 “Campus in Camps” initiative and the work of Isayev (2017). |

| 5 | Throughout my academic career I have been dedicated to disability rights and women’s rights in scholarship, service, and teaching (Trentin 2014, 2015a, 2016a). |

| 6 | The subject is not new but has experienced a renewed interest of late: Columbia University recently hosted a conference on “Refuge and Refugees in the Ancient World”, November 11–12, 2016; and Elena Isayev at the University of Exeter has led a series of Classics courses based on her research in migration, mobility, and belonging (2016–2018). |

| 7 | 1,112,406 from 2013–2017. In 2017, 29,718 migrants arrived on the Greek islands, 42% of whom were Syrians: (UNHCR 2018). In 2016, 47% of Syrian refugees on the Greek islands were children, 11% of whom travelled alone: (UNHCR 2016a). Global statistics for the Syrian crisis: (UNICEF 2018). |

| 8 | See the Greek Ministry of Education Research and Religious Affairs (2017, p. 73). |

| 9 | Greek Ministry of Education Research and Religious Affairs (2017). |

| 10 | On the vital role of curiosity in education, see Freire (1970, 2001); on building excitement in the classroom, see hooks (1994); on the transformative effects of education, see Mezirow (2000). |

| 11 | In 2015: 120,804; in 2016: 33,969; in 2017: 6294; and as of January 2018: 119. UNHCR (2015, 2016b). |

| 12 | UNHCR (2017a), June 20. All of the Aegean island camps are overcrowded. |

| 13 | Refugee Rights Data Project (2017a, p. 4). |

| 14 | The UNHCR remains “very concerned at the situation of refugees and migrants” in the camps on the Greek islands (UNHCR 2017b, p. 41). See also Dalal (2017), in this volume. |

| 15 | ‘Action for Education’ charity #1099682. From November 2016–January 2018 the schools and youth centre were run by the Swiss NGO ‘Be Aware and Share’. |

| 16 | At the time of publication, the primary school was passed to the Greek NGO Metadrasi. |

| 17 | Volunteers from the refugee community, speaking Arabic and Farsi, also provided language and translation support. |

| 18 | See the vision of ‘Action for Education’, accessible at: www.actionforeducation.co.uk. |

| 19 | Perhaps colonial, these lessons aimed at exploring cultural unity through diversity. See Rohde (2017) in this volume. On (post-)colonial discourses in Classics, see Goff (2005). |

| 20 | Segatto (2017, p. 4). |

| 21 | This activity was modified from the “Simulated Digs” lesson plan via the Education Department of the Archaeological Institute of America: https://www.archaeological.org/pdfs/education/digs/Digs_layer_cake.pdf. |

| 22 | This activity was modified from the “Shoebox Dig” activity via the Education Department of the Archaeological Institute of America: https://www.archaeological.org/pdfs/education/digs/Digs_shoebox.pdf. |

| 23 | Example: North Syrian aryballos from grave 215, and Egyptian faience scarabs, both dated to the eight century BCE, Pithekoussai. See Buchner (1966, pp. 6–8). |

| 24 | On museum engagement and refugee communities, see Skartveit and Goodnow (2010). |

| 25 | Segatto (2017, p. 3). |

| 26 | BBC News (Turner 2016). On the destruction of cultural heritage and current debate about reconstruction projects (by whom? for whom?), see (Bond 2016; Munawar 2017). |

| 27 | On Idrimi, see: https://blog.britishmuseum.org/idrimi-the-3500-year-old-refugee/ |

| 28 | On the “Living History” of Syria, see: https://www.agakhanmuseum.org/syria-living-history, |

| 29 | On the works of Issam Kourbaj, see: https://www.classics.cam.ac.uk/museum/exhibitions/exhibitions/lost |

| 30 | Segatto (2017, p. 3). |

| 31 | In ancient Greece, xenia or guest-friendship, was defined by a mutual respect between stranger and host, whereby a host would provide hospitality to strangers in need. On the practice of xenia, see Herman (2002). |

| 32 | See the recent work of Effrosyni Kostara (2016) on Greek drama and transformative learning theory. |

| 33 | On the problematic and politically charged use of ‘civilized’ and ‘civilization’, see Beard (2018). On colonial and postcolonial discourses in Classics, see Goff (2005). |

| 34 | Rhodan (2015) in Time. |

| 35 | For current debate on the use of “trigger-warnings” see Godderis (2016); on addressing difficult topics in the Classics classroom, see Rabinowitz and McHardy (2014). |

| 36 | For examples of abuse, see the Refugee Rights Data Project (2017b, 2017c). |

| 37 | Gabriel (2003, p. 631): “As individuals, we may display hospitality, … But as members of organizations, hospitality does not enter our thinking. Borders are borders. They must be respected, defended, and patrolled with closed ears to the plight of the Other. Those outside the borders are kept outside—their voices ignored until they seek to test the borders, something we experience as a violation and a threat. Their stories are irrelevant. Unlike the Homeric boundaries which may be crossed under the tradition of hospitality, redefined or disregarded, ours appear impermeable.” |

| 38 | For the mythological evidence for Homer in Chios, see West (1999). |

| 39 | See the Khora website for more information, www.khora-athens.org. |

| 40 | This is not an uncommon response, even among students from western backgrounds. The nudity of Greek statues was recently explored at the British Museum’s exhibit Defining Beauty: The Body in Ancient Greek Art (2015). |

| 41 | On the wearing of headdresses, women’s rights and religious freedom, see Ferrari and Pastorelli (2016). |

| 42 | See above Section 5. Archaeology and Cultural Heritage. On the latest ban exporting antiquities from Syria, Iraq, and other states in the Middle East, see the United Nations Security Council Resolution 2199 (February 2015) via the UNESCO website at: www.unesco.org/new/fileadmin/MULTIMEDIA/HQ/ERI/pdf/UN_SC_RESOLUTION_2199_EN.pdf. |

| 43 | A thoughtful essay on teaching uncomfortable subjects with students of varying religious backgrounds comes from Strolonga (2014). |

| 44 | The Greek Tourism Confederation projected 30 million tourists would visit in 2017; official data is not yet available. |

| 45 | I am grateful to Joe Druce for gifting me a copy of Freire’s book. |

| 46 | hooks (1994, 2004), defines the pedagogy of liberation as “education as a practice of freedom” where teachers and students share in the intellectual and personal growth of one another, with an openness of heart and mind, building community and transgressing boundaries of body, mind, and spirit. |

| 47 | See Freire and Faundez (1989), “The rediscovery of the Other” (pp. 71–72). |

| 48 | For reasons of anonymity and privacy, links have not been included here. |

| 49 | They became true border-crossers! See Giroux (2005). |

| 50 | Freire (1970, p. 65). |

© 2018 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).