Uncovering Culture and Identity in Refugee Camps

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. |

| 2 | World Food Program. |

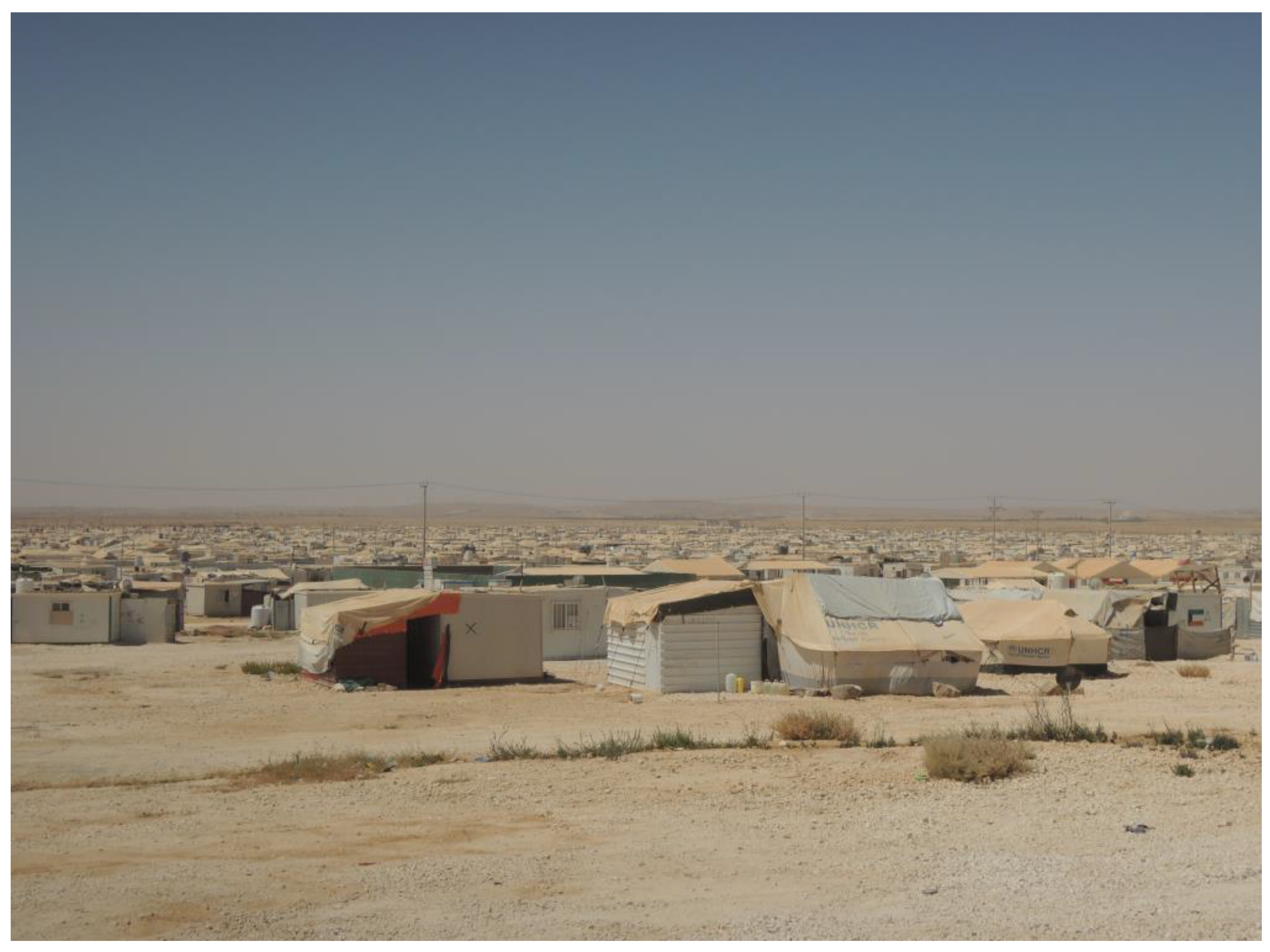

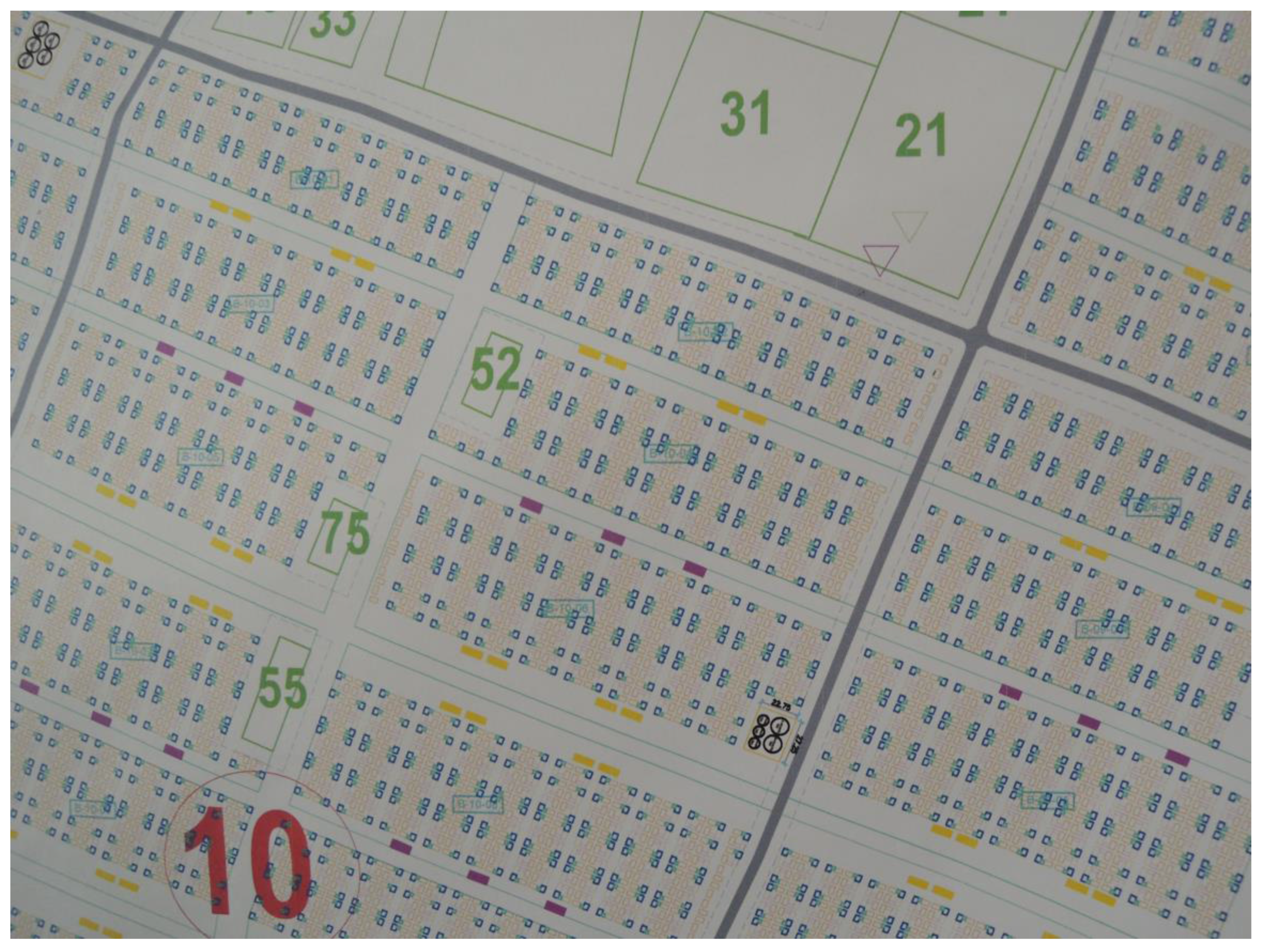

| 3 | This text is based on the fieldwork notes of the author, conducted between November 2016 and April 2017 in Zaatari camp as part of his Ph.D. research: “Understanding the Morphology of Zaatari Camp: The Role of Culture, Representations of Home and the Social Structuring of Space” at TU Berlin. Taking an ethnographic approach, the study looks at ‘Home’ as a microcosm to understand the social structuring of the camp’s space and reveal the different factors related to it. Additionally to the previously mentioned fieldwork, the study builds on the author's experience and engagement in Syrian and Palestinian camps in Jordan since 2014 as a researcher, consultant and tutor for several workshops and studies. |

© 2017 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dalal, A. Uncovering Culture and Identity in Refugee Camps. Humanities 2017, 6, 61. https://doi.org/10.3390/h6030061

Dalal A. Uncovering Culture and Identity in Refugee Camps. Humanities. 2017; 6(3):61. https://doi.org/10.3390/h6030061

Chicago/Turabian StyleDalal, Ayham. 2017. "Uncovering Culture and Identity in Refugee Camps" Humanities 6, no. 3: 61. https://doi.org/10.3390/h6030061

APA StyleDalal, A. (2017). Uncovering Culture and Identity in Refugee Camps. Humanities, 6(3), 61. https://doi.org/10.3390/h6030061