Children and Trauma: Unexpected Resistance and Justice in Film and Drawings

Abstract

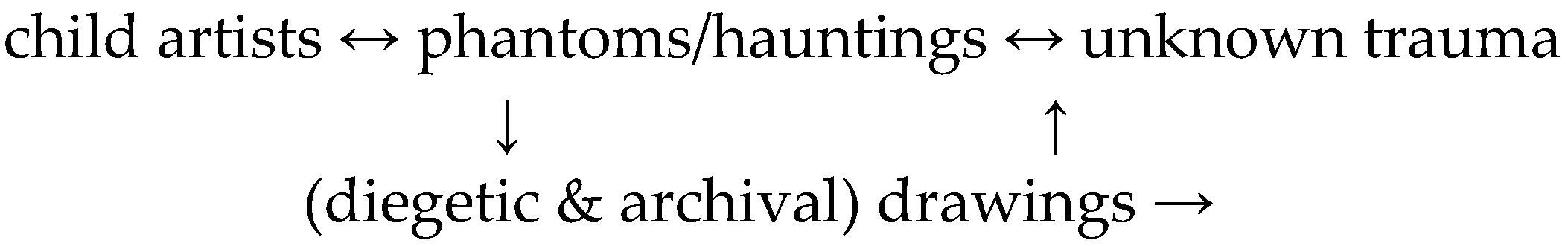

:The children’s drawings, much the same as the photographs and the image of the wounded child, also show too little and too much, but the power of these images remains undeniable. They evoke an emotional response even when standing alone, and emotion draws the viewer in—counteracting a potentially disinterested or distant stance. They serve as a silent witness of the child artists’ traumatic pasts and validate pain—potentially with or without a narrative attached to them. However, as with the following analysis of del Toro’s film and the situation of the traumatic within a narrative of sense (narrative memory + the restoration of sense), I have chosen to contextualize the drawings separately from the film by providing information obtained from the Archive and personal correspondence.Photography, the art of de- and re-contextualizing, can isolate and freeze the moment, much in the way that violence ruptures our present from our past and freezes time in a simple before/after… The violent separation of each object, bracketed off from the rest, also invokes the pain and isolation of exile, the life lived out of place. The photograph unsettles–showing simultaneously too little and too much.

Representations of the Traumatic

DR. CASARES. ¿Qué es un fantasma? Un evento terrible condenado a repetirse una y otra vez. Un instante de dolor, quizás. Algo muerto que parece por momentos vivo aún. Un sentimiento suspendido en el tiempo, como una fotografía borrosa, como un insecto atrapado en ámbar.

The voice-over is repeated at the end of the film with an additional line revealing the Doctor’s own connection to phantoms. The film’s narration, mostly linear and chronological except for several flashbacks, is united by the repetition of the beginning voice-over, paired with a new set of shots, at the end. The initial establishing sequence begins with a slow movement towards a darkened doorway [“¿Qué es un fantasma? Un evento terrible condenado a repetirse una y otra vez.”], then cuts [sound of the cargo doors opening] to the underside of a plane as the cargo doors open and a bomb drops into a rain-filled sky illuminated by various explosions and fires on the ground. The shot ends with the closing of the cargo doors, and the next one starts with the image of a wounded child (later identified as Santi) lying on the ground [“Un instante de dolor, quizás.”]. His head has a large gash that is bleeding out onto the ground as another boy (later revealed to be Jaime) touches the wound, bloodying his own fingers and face in the process, and cries [“Algo muerto que parece por momentos vivo aún.”]. The fourth shot is of a murky body of water with an initially unknown object that appears to be sinking [“Un sentimiento suspendido en el tiempo,”]. A boy’s face is finally visible [“como una fotografía borrosa,”], his body descending deeper into the water, while the camera moves up and outside of the water to show the older boy from the third shot, still crying, as he gazes into the body of water, now visibly a cistern [“como un insecto atrapado en ámbar.”]. The fourth shot is connected to the fifth, final shot as the cistern scene dissolves into another murky fluid with unrecognizable objects floating in it. These objects are eventually identified as fetuses with exposed spinal cords or spina bifida, an allusion to the devil’s backbone from which the film derives its name.DR. CASARES. What is a phantom? A terrible event condemned to repeat itself time after time. An instant of pain, perhaps. Something dead that at times seems still alive. A sentiment suspended in time, like a blurred photograph, like an insect trapped in amber.

The wound and the voice that cries out from it are tied to the belatedness of trauma, its unassimilated nature, and its being not known at the moment of wounding; for these reasons, the “missed” trauma may return to haunt those who survive the initial wounding (p. 4). El espinazo revisits a past violence through the phantom child’s return to (his haunting of) the place of trauma (a concealed murder). The use of wounded phantoms in the film is literally a return to the haunting of trauma in trauma studies. The traumatic is given materiality in the frightful appearance of the wounded phantom child Santi while the abject that produces repulsion is also unexpectedly re-appropriated as both a warning of future violence and a cry for justice for past violence. Through traumatic imagery, Santi and the other orphans are converted into sites of traumatic memory (symbolically) and (literal agents of) justice, one founded in natural law and the supernatural—both of which must serve the victims in the absence of positive laws and guardians to protect them.Just as Tancred does not hear the voice of Clorinda until the second wounding, so trauma is not locatable in the simple violent or original event in an individual’s past, but rather in the way that its very unassimilated nature–the way it was precisely not known in the first instance–returns to haunt the survivor later on.

The children’s drawings have the power of expressing the inexpressible (to bear witness to the inarticulate experience of the inside)—connected to subjectivity (requires the possibility of a witness for Oliver), response-ability, ethical obligations, and justice. For Oliver, “Response-ability is never solitary” (p. 91) (unlike the traumatic narrative addressed to no one). The drawings, when viewed as symbolic expressions of “the inside,” request and require an audience who will be ethically responsible.Yet in order to reestablish subjectivity and in order to demand justice, it is necessary to bear witness to the inarticulate experience of the inside. … It is the tension between finite understanding linked to historical facts and historically determined subject positions, and the infinite encounter linked to psychoanalysis and the infinite responsibility of subjectivity that produces a sense of agency. Such an encounter necessarily takes us beyond recognition and brings with it ethical obligation.

In this context, the drawings can function as a means for children to address themselves to others and for human rights organizations through children to work against the forces of violence—the annihilation of social relations and of existence itself. Daniel Feierstein (2014) speaks of disappearance as more than murder in that it is an obliteration of one’s existence. As a means of resisting the obliteration of the Other and as a reclamation of existence, the drawings attest to a violence that “disappeared” people. They are a tool employed to counteract the process of annihilation and re-establish subjectivity through a confirmation of address-ability and response-ability by “bear[ing] witness to the inarticulate experience of the inside” (Oliver 2001, p. 90).To conceive of oneself as a subject is to have the ability to address oneself to another, real or imaginary, actual or potential. Subjectivity is the result of, and depends on, the process of witnessing—address-ability and response-ability. Oppression, domination, enslavement, and torture work to undermine and destroy the ability to respond and there-by undermine and destroy subjectivity.

Concluding Thoughts on Fiction and the Archive

The idea of haunting as a means of revealing past violence with the clear intent of pursuing justice is particularly evident in El espinazo, where Jaime’s drawing becomes a tool for natural law that works in tandem with the supernatural (in the absence of positive laws). As the orphans answer the phantom’s cry for justice, their bodies, repositories marked by violence, carry traumatic memory forward to a final reckoning in which the traumatized child’s body is also the weapon or force that claims justice. With the archival children’s drawings, the use of visual recreations of unresolved past violence is also utilized for the pursuit of a just recognition of wrongs committed, although within the framework of positive law and human rights work in exile. The archival drawings, as a call for response-ability and address-ability, pursue justice through COSOFAM’s propagation of interventionist strategies (using children’s drawings to expose violence and request intervention) and demand for accountability on the part of the Argentine State for the “missing” bodies connected to the names listed on the postcards. I have not currently located a document at the Archive stating that any action was taken on the part of the judge in question, but it is possible that a record exists. This would be an intriguing line of inquiry for future studies.

The idea of haunting as a means of revealing past violence with the clear intent of pursuing justice is particularly evident in El espinazo, where Jaime’s drawing becomes a tool for natural law that works in tandem with the supernatural (in the absence of positive laws). As the orphans answer the phantom’s cry for justice, their bodies, repositories marked by violence, carry traumatic memory forward to a final reckoning in which the traumatized child’s body is also the weapon or force that claims justice. With the archival children’s drawings, the use of visual recreations of unresolved past violence is also utilized for the pursuit of a just recognition of wrongs committed, although within the framework of positive law and human rights work in exile. The archival drawings, as a call for response-ability and address-ability, pursue justice through COSOFAM’s propagation of interventionist strategies (using children’s drawings to expose violence and request intervention) and demand for accountability on the part of the Argentine State for the “missing” bodies connected to the names listed on the postcards. I have not currently located a document at the Archive stating that any action was taken on the part of the judge in question, but it is possible that a record exists. This would be an intriguing line of inquiry for future studies. Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alicia Raquel Puchulu de Drangosch Archive. Donated 2014. Comisión de Solidaridad con Familiares de Desaparecidos en Argentina (COSOFAM). Eight Postcards Imprinted with Children’s Drawings. No date. Listed in the “Catálogo de Fondos Escritos/Audiovisuales/Fotográficos”. Buenos Aires: Archivo Nacional de la Memoria, Accessed on 8 September 2015.

- Arendt, Hannah. 1958. The Origins of Totalitarianism. Cleveland and New York: Meridian Books, The World Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Bergero, Adriana. 2010. Espectros, escalofríos y discursividad herida en El espinazo del diablo: El gótico como cuerpo-geografía cognitiva-emocional de quiebre. No todos los espectros permanecen abandonados. Project Muse 125: 433–56. [Google Scholar]

- Calveiro, Pilar. 1998. Poder y Desaparición: Los Campos de Concentración en Argentina. Buenos Aires: Ediciones Colihue. [Google Scholar]

- Calvo, A., and Archivo Nacional de la Memoria. 2016. January 7. Email message to author.

- Caruth, Cathy. 1996. Unclaimed Experience: Trauma, Narrative, and History. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- El espinazo del diablo [The Devil’s Backbone], 2001. Toro Guillermo del, director. Production Companies: El Deseo S.A., Tequila Gang, and Anhelo Producciones. DVD.

- Feierstein, Daniel. 2014. Genocide as Social Practice: Reorganizing Society under the Nazis and Argentina’s Military Juntas. Translated by Douglas Andrew Town. New Brunswick, and London: Rutgers University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Felman, Shoshana, and Dori Laub. 1992. Testimony: Crises of Witnessing in Literature, Psychoanalysis, and History. New York and London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner, C., and Light House Program at South Coast Hospice. 2017. February 28. Email message to author.

- Gatti, Gabriel. 2011. Identidades Desaparecidas: Peleas por el Sentido en los Mundos de la Desaparición Forzada. Buenos Aires: Prometeo Libros. [Google Scholar]

- Lázaro-Reboll, Antonio. 2007. The Transnational Reception of El espinazo del diablo (Guillermo del Toro 2001). Hispanic Research Journal 8: 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyano, E., and Suarez del Archivo nacional de la memoria. 2016. October 16. Email message to author.

- Oliver, Kelly. 2001. Witnessing: Beyond Recognition. Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ranciere, Jacques. 2009. The Emancipated Spectator. Translated by Gregory Elliott. London and New York: Verso. [Google Scholar]

- Rocha, Carolina, and Georgia Seminet. 2012. Introduction. In Representing History, Class, and Gender in Spain and Latin America: Children and Adolescents in Film. Edited by Carolina Rocha and Georgia Seminet. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, Diana. 2009. Cuerpos políticos/Body Politics. In Body Politics: Políticas del Cuerpo en la Fotografía Latinoamericana. Edited by Marcelo Brodsky and Julio Pantoja. Buenos Aires: La marca editora, pp. 20–31. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Kolk, Bessel A., and Onno van der Hart. 1995. The Intrusive Past: The Flexibility of Memory and the Engraving of Trauma. In Trauma: Explorations in Memory. Edited by Cathy Caruth. Baltimore and London: The John Hopkins University Press, pp. 158–82. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | IMPORTANT NOTE: Pictures of the archival drawings were obtained with the permission of the Archivo Nacional de la Memoria [National Archive of Memory] in Argentina and cannot be reproduced for monetary gain or without authorization. I have not included the drawings within the text due to restrictions regarding their dissemination. |

| 2 | According to the Catálogo de Fondos Escritos/Audiovisuales/Fotográficos [Catalogue of Written/ Audiovisual/Photographic Collections] (Alicia Raquel Puchulu de Drangosch Archive 2014), Alicia Raquel Puchulu de Drangosch founded and was president of COSOFAM in the Netherlands during the Argentine military dictatorship. She was forced to flee Argentina to ensure her and her family’s safety. I discovered the children’s drawings/postcards in her archive, part of a collection donated in 2014 by her daughters to the Archivo Nacional de la Memoria in Buenos Aires, thanks to the Ben and Rue Pine travel grant (2015). |

| 3 | My initial research findings on the comparative study of children’s drawings in del Toro’s films and those from the archive in Argentina were first presented at the ACLA Annual Meeting at Harvard University in 2016. Since then, I have altered and expanded upon my initial conclusions based on new information. |

| 4 | This theme of the traumatic past/phantoms haunting the present is represented in El orfanato (2007), directed by J.A. Bayona with del Toro as an executive producer. |

| 5 | I recognize that many scholars might disagree with my decision to juxtapose representational strategies and purposes of a fictional interpretation with archival drawings, and I want to emphasize that my intention is to place them in dialogue with each other, not to suggest that the Spanish Civil War and the Argentine military dictatorship were the same. They are distinct historical events, but that does not mean reconstructions of violence pertaining to either period cannot pursue similar strategies or purposes. |

| 6 | Translations from Spanish to English are mine; please note that I have attempted to maintain the original meanings instead of translating word for word. |

| 7 | Names of personal correspondents have been shortened for privacy. |

| 8 | Information was also obtained via email from I. Suarez. “Archivo nacional de la memoria—Cartas postales de COSOFAM.” Email message to author, 27 May and 14 September 2016. |

| 9 | Caruth appropriates the symbols of the wound and the voice from Freud’s analysis of a story, recounted by Tasso in the epic Gerusalemme Liberata [Jerusalem Delivered] (1581), about the knight Tancred who accidentally wounds his beloved Clorinda (Caruth 1996, p. 2). |

| 10 | Carlos pronounces the name “Santi,” carved on the wall by the bed. |

| 11 | One example is the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance (December 2006). |

| 12 | The child artists were Moyano, her sisters, and cousin. |

| 13 | Several supporting entities are also listed: CO. SO. FAM. (COSOFAM), A.F.U.D.E., Nederlandse Kinderraad [Netherlands Council for Children], Komitee Twee [Committee Two], Kerk en Vrede [Church and Peace], I.F.O.R., Stichting Oecumenische Hulp [Foundation for Ecumenical Assistance], Kerken en Vluchtelingen [Churches and Refugees], and N.C.O., respectively. |

| 14 | See also, Marguerite Feitlowitz. 2011. A Lexicon of Terror: Argentina and the Legacies of Torture, Revised and Updated with a new Epilogue. Oxford: Oxford University Press. |

© 2018 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Robinson, C.M. Children and Trauma: Unexpected Resistance and Justice in Film and Drawings. Humanities 2018, 7, 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/h7010019

Robinson CM. Children and Trauma: Unexpected Resistance and Justice in Film and Drawings. Humanities. 2018; 7(1):19. https://doi.org/10.3390/h7010019

Chicago/Turabian StyleRobinson, Cheri M. 2018. "Children and Trauma: Unexpected Resistance and Justice in Film and Drawings" Humanities 7, no. 1: 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/h7010019

APA StyleRobinson, C. M. (2018). Children and Trauma: Unexpected Resistance and Justice in Film and Drawings. Humanities, 7(1), 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/h7010019