Troubadours & Troublemakers: Stirring the Network in Transmission & Anti-Transmission

Abstract

:transport [of a message] transforms—Régis Debray

[I]t is one of the important tasks of poems to short-circuit the transparency that words have for the signified and which is usually considered their advantage for practical uses.—Rosmarie Waldrop

I am a DJ. I am what I play.—David Bowie

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight35

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. A Sample Index of Trouble Song lyrics, Typically in Order of Appearance in Trouble Songs: A Musicological Poetics

Appendix B. Notes (via Andrew Klobucar, as Presented at the Electronic Literature Organization 2014 Conference Panel “Troubadours of Information: Aesthetic Experiments in Sonification and Sound Technology”)

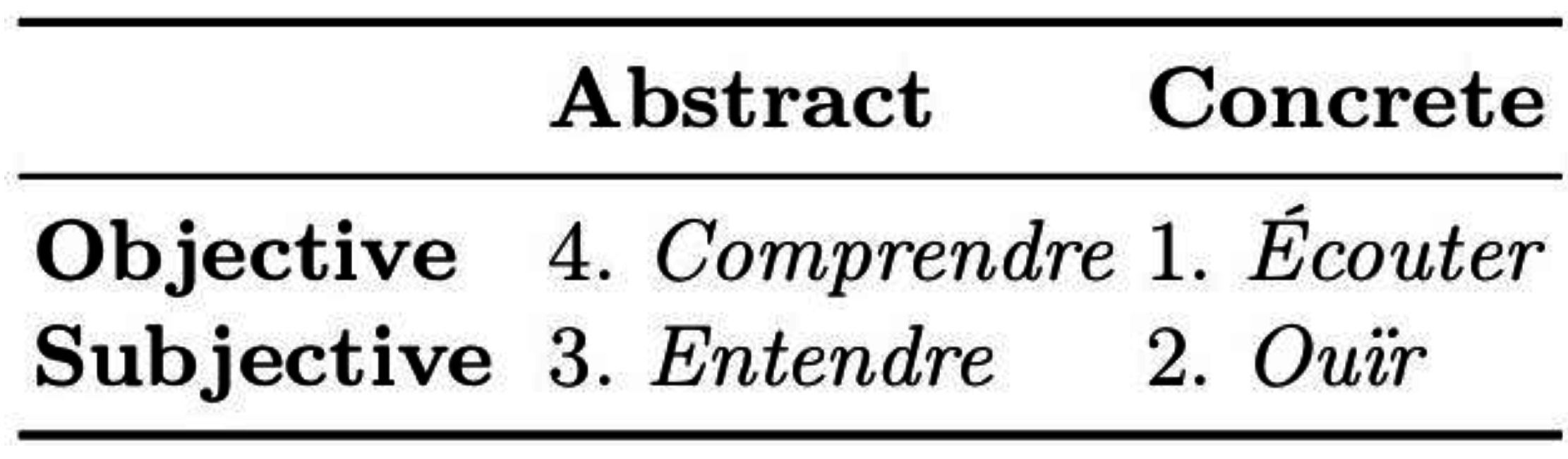

- Écouter, is listening to someone, to something; and through the intermediary of sound, aiming to identify the source, the event, the cause, it treats the sound as a sign of this source, this event (Concrete/Objective).

- Ouïr, to perceive by the ear, to be struck by sounds, it is the crudest level, the most elementary of perception; so we “hear”, passively, lots of things which we are not trying to listen to nor understand (Concrete/Subjective).

- Entendre, here, according to its etymology, means showing an intention to listen [écouter], choosing from what we hear [ouïr] what particularly interests us, thus “determining” what we hear (Abstract/Subjective).

- Comprendre, means grasping a meaning, values, by treating the sound like a sign, referring to this meaning as a function of a language, a code (semantic hearing; Abstract/Objective).

References

- Cascone, Kim. 2004. The Aesthetics of Failure: ‘Post-Digital’ Tendencies in Contemporary Computer Music. In Audio Culture: Readings in Modern Music. Edited by Christoph Cox and Daniel Warner. Continuum: New York, pp. 392–99. [Google Scholar]

- Casillo, Robert. 1985. Troubadour Love and Usury in Ezra Pound’s Writings. Texas Studies in Literature and Language 27: 125–53. [Google Scholar]

- Debray, Régis. ; Translated by Martin Irvine. 1999. What Is Mediology? Le Monde Diplomatique, 32. [Google Scholar]

- Gaye, Marvin. 1972. Trouble Man. Hollywood: Tamla. [Google Scholar]

- Gaye, Marvin. 1971. What’s Going On. New York: Tamla, LP record. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, Jeff T. 2015. Trouble Songs: A Musicological Poetics. Jacket2. May 18. Available online: http://jacket2.org/article/trouble-songs (accessed on 5 April 2017).

- Johnson, Jeff T. 2017. Trouble Songs: A Musicological Poetics. Earth, Milky Way: Punctum Books. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | Originally presented at the Electronic Literature Organization 2014 conference panel “Troubadours of Information: Aesthetic Experiments in Sonification and Sound Technology,” with Andrew Klobucar. During the conference panel presentation, the essay was projected behind the speaker, who was accompanied by clips from referenced songs. Each prose block was laid out in landscape view, counterbalanced by associated footnotes. This setup was intended to acknowledge and engage multiple nodes and modes of audience attention, while suggesting a verse-chorus or call-and-response form to the text. Notes were read selectively, and improvised. See Appendix B (Figure A1) for panel framework. |

| 2 | See (Johnson 2015; Johnson 2017)). The trouble singer is a figure who sings “trouble” in place of “actual” trouble, thus temporarily dispelling the latter and allowing the audience to commune over this exorcism while sharing a sense of their burdens. The Trouble Song summons trouble in an aestheticized form that not only shields the audience (temporarily) from its worries, but protects the singer from a potentially debilitating candor (or public exposure). Meanwhile, the Trouble Song functions as a screen onto which the audience (and the singer) may project their own troubles. |

| 3 | We may conflate DJ, Mixmaster and MC, while allowing each term to add layers to our key figure, the trouble singer. (We adopt terminology from the Trouble Songs project, where Trouble Song is a proper noun but trouble singer is not, though the latter usage may appear inconsistent here with the other key figures: DJ, Mixmaster and MC. Let’s say the trouble singer is a generic figure that encompasses the other more specific figures.) We think of the DJ (disc jockey) as broadcaster and collector/controller of records—or media curator. The Mixmaster moniker emphasizes technique (turntablism) and the signal/noise interface signified by the scratch. (We might further explore this path in relation to Kim Cascone’s consideration of glitch music as the product of digital tools that enable the foregrounding of error and signal failure, so that audio processing tools, like the turntable, become instruments rather than media. See (Cascone 2004) Meanwhile, the Mixmaster’s crossfade (via multiple turntables, along with other devices including laptop and CD console) takes us across media and directs transmission flows between sources. The MC (mic controller) is the rapper or maker of toasts, whose verbal dexterity and feel for the audience serve to monitor and inflect communal affect. We will toggle between these terms to emphasize various roles and skills embodied by our contemporary trouble singer, even while the DJ may combine these roles (as the DJ needs the Mixmaster’s technological skills and the MC’s genius). Meanwhile, these footnotes will tend to sing a more formal song than the body text, as a more explicit academic backup, or a hybrid (re)mix of Trouble Songs tones, or a straight cover of the same song, a simulcast transmission. Pardon the mixed (troubled?) metaphor. |

| 4 | in her multiple guises |

| 5 | As with the media operated by the Mixmaster, they are a confluence of signals. |

| 6 | just as poem becomes song |

| 7 | Here we might add that the troubadour’s reputation for knowledge of technique and form evokes the technical (and technological) prowess of the Mixmaster, just as the troubadour’s vocality recalls (or preforms) the MC’s mic skills. |

| 8 | Further along the road, we note the country blues tradition of itinerant musicians after emancipation—as discussed by Leroi Jones in Blues People, and Angela Y. Davis in Blues Legacies and Black Feminism—and the ways these ambulatory cultural practices abet the floating folk lyric, where recognizable phrases hop from song to song and place to place (see also Greil Marcus, “The Old, Weird America” and Luc Sante, “The Invention of the Blues”). This line of thinking is elaborated in Trouble Songs: A Musicological Poetics. |

| 9 | Consider the DJ’s bag of records, many of which carry the signal of the MC, whose song travels with or without her. Still, the DJ may toast (to sample a term from the origins of hip-hop, at the emergence of the MC’s distinct role) over the top of that signal, spinning a new verse over the spinning record(s). |

| 10 | Rather than confuse singer for song, we might (remixing Cascone) conflate singer and song with device, and device with the failure of the device. We might then amplify the glitch: synechdochal failure, or device failure as device, or failure for device. The device, too (like or as the song), might carry us (temporarily) away from trouble—or replace one trouble with another. Glitch can be transformative or transporting, but it also signals imminent crash. |

| 11 | That is, if we bracket (or delay) for a moment the advent of electromagnetic wave transmission, which will extend and further complicate song travel. |

| 12 | Again we go back (and forward) to early 20th century country blues and folk lyric mobility and transfer. This is worth mentioning again because itinerant blues may be considered in the context of this essay as a reference point connecting the troubadour to our contemporary DJ figure—where allusion, floating lyric and sample wax transhistorical. |

| 13 | Indeed, the etymological commentary opens, “The origin of the verb itself is questioned.” |

| 14 | Whether this figure might also either be a troubleshooter, or might seem to require troubleshooting, remains to be seen. |

| 15 | Here the etymological connection between troubadour and the medieval Latin tropus, via trope (again per OED) connects with verse, which suggests a sense-making prosodic arrangement we might also think of as version, mix or flow. This related sense of trope as verse phrase also evokes a (call and) response as introduced in the medieval Western Church and carried through MC flow. |

| 16 | The successful Trouble Song lyric balances pathos and detail with a generic sense of inclusiveness and discretion, which protects singer/listener privacy while allowing for communal feeling and commiseration. |

| 17 | which she turns, literally, a remix of trope’s etymology from Greek tropos, ‘turn’ |

| 18 | making use of the MC’s geniality and the Mixmaster’s technique, which are no sweat (see here Erik B. & Rakim’s foundational hip-hop album Don’t Sweat the Technique). |

| 19 | The song finds us by ear and by eye. The DJ sees what she plays, from cover to groove, while the Mixmaster sees sounds as wave forms to be manipulated, amplified, numerically sampled, patterned as information. Meanwhile, at least in retrospect, we all see trouble coming. |

| 20 | Allow us to reintroduce the troubadour, who models a form of cultural remix, where historical traditions are de-contextualized, then re-contextualized in the mix for contemporaneous situations and loci. Much is brought to the transhistorical party, including more trouble: a provisional order is established with a wink, set up to be knocked down as the revelry gets underway. |

| 21 | As we’ll see (and can hear for ourselves), What’s Going On (Gaye 1971), from which this cut comes, is full of trouble. A year later, Gaye graces the album cover of the soundtrack to Trouble Man, above a spliced action shot of the lead film actor (the composition shaped in a T for Trouble with a capital T, while the O in trouble and the A in Marvin are shot through with extra holes). He sings its title song and adds vocal textures to a few other numbers, but the album is mostly instrumental and incidental accompaniment to the Blaxploitation film by the same name. This is a whole other world of (representational) trouble, outside the scope of this essay, though in terms of Trouble Songs’ musicological poetics, we might say the Trouble Man character Gaye doubles for on the soundtrack plays the part for those who want a taste of trouble without paying for their meal: “Trouble” in place of trouble, as Trouble Songs has it, and as explored above (or below) in a moment. |

| 22 | or gets around |

| 23 | And let’s recall the Mixmaster’s crossfader, which re-places or conflates one song/signal for another, and makes possible the potentially infinite dilation of the break (as we’ll see). |

| 24 | And yuck, etc. This heteronormative and sexist display is ripe, of course, for drag dressing-up-as-dressing-down via torch song. |

| 25 | a refrain, to refrain: She has no intention of calling trouble itself, except to call it “trouble”—to re-place trouble (elsewhere, anywhere but here). |

| 26 | city to city, beat to beat. |

| 27 | Here we find Wikipedia’s entry for hook to be of use (recognizing also the suitability of this source, as cultural and linguistic sample and remix): musical idea or short riff. |

| 28 | Archetypal breakbeats come from James Brown’s “Funky Drummer” or The Incredible Bongo Band’s “Apache,” as mixed on two turntables by DJ Kool Herc (circa early ’70s in The Bronx), as he cut between two copies of the same record to extend the drum break for the benefit of the b-boys and b-girls on the dance floor. |

| 29 | see also Appendix A: “Trouble Will Find You” (from Trouble Songs: A Musicological Poetics, in which a version of this essay appears). |

| 30 | or, again, two turntables linked by crossfader. |

| 31 | Nor does the troubadour arrive (though he attends the song)—always out of place, the troubadour (like the Mixmaster et al.) is stuck in a loop of here/there. Just so, the trouble singer rides the break (sic) of trouble/“trouble.” |

| 32 | And here we can further illustrate and complicate the matter with reference to electromagnetic radio waves and wireless communication, where source and signal translocate and exist in multiple and proliferant destinations, and the nature, form and format of the source is transmogrified. |

| 33 | where (in this verse) technique is delivery, and device (be it metaphor, guitar or computer) is technology. |

| 34 | the medium and the tool/instrument. |

| 35 | Here we turn 8 on its side, lower it to the turntable, and loop the next track. |

| 36 | It’s up to you, of course. If you do keep the song spinning, and listen through Gaye’s delivery to the words, which are perfectly clear even as they soar above signification, you’ll hear a cocaine blues, probably, but you’ll also hear a love song, and a song of brotherhood. You’ll also hear, in the last, circling verse, the boy who makes slaves out of men to whom the song—and the singer—is hooked. You might also notice the way the previous song, “What’s Happening Brother,” lands on the opening vocal oohs of “Flyin’ High,” making the connection between the returning soldier and the troubled mind. Can’t find no work, can’t find no job my friend sings the soldier in “What’s Happening Brother,” and the grounded pilot answers In the morning, I’ll be alright, my friend, before correcting himself later in “Flyin’ High”: Well I know I’m hooked, my friend. He knows well the answer to the soldier’s final question, What’s been shakin’ up and down the line (and the soldier knows he knows—just like the album title, his question has no question mark): Without ever leaving the ground/…I ain’t seen nothing but trouble baby. |

© 2017 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Johnson, J.T. Troubadours & Troublemakers: Stirring the Network in Transmission & Anti-Transmission. Humanities 2017, 6, 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/h6020021

Johnson JT. Troubadours & Troublemakers: Stirring the Network in Transmission & Anti-Transmission. Humanities. 2017; 6(2):21. https://doi.org/10.3390/h6020021

Chicago/Turabian StyleJohnson, Jeff T. 2017. "Troubadours & Troublemakers: Stirring the Network in Transmission & Anti-Transmission" Humanities 6, no. 2: 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/h6020021

APA StyleJohnson, J. T. (2017). Troubadours & Troublemakers: Stirring the Network in Transmission & Anti-Transmission. Humanities, 6(2), 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/h6020021