Abstract

This case study of I’ll Be Fine describes my creation of a passively interactive, “playable” movie for networked screens, and outlines reasons why this story is an instance of a new genre of storytelling that might be called “playable narrative”. Although the piece is interactive, and while it seems to satisfy certain features of the activity of play, I’ll Be Fine does not offer opportunities for strategy, competition, or closure, and does not proceed towards goals or outcomes, but seeks to construct meaning cinematically, proceeding sequentially across planes or layers, and using a spatial design much like the cinematic compositional scheme of background, middle ground, and foreground. While a general model for the spatial construction of playable movies is outside the scope of this writing, the following description of my design concepts are meant to delineate certain aspects of working with spatiality and playability while constructing an interactive story.

1. Introduction

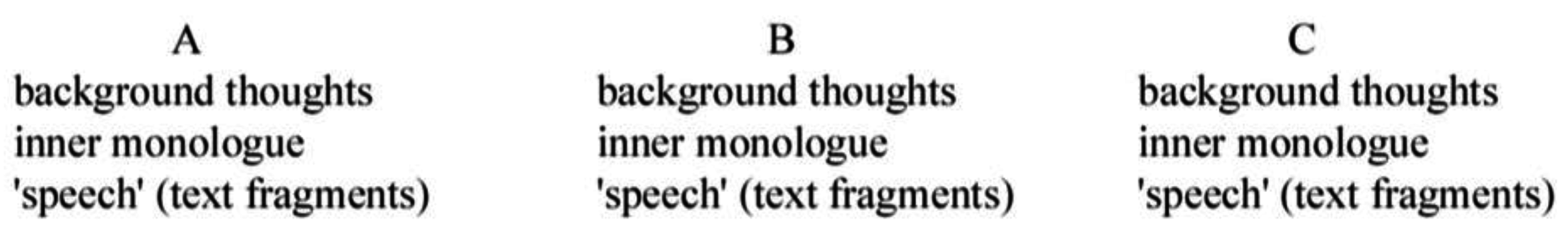

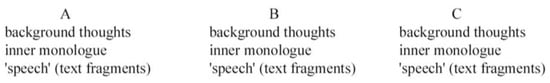

As its title suggests, I’ll Be Fine is a movie about individual reactions to and recoveries from a romantic breakup. I designed the project to play in storefront windows, at street level, as a “walk up” interactive, a new kind of public media form, one which depends on casual, or “passive”, interaction from viewers passing by on the sidewalk [1]. I installed this work at Industry City in Brooklyn, New York, for Creative Tech Week, an industry-wide gathering for creative technologists held in New York from 29 April to 8 May 2016, sponsored by Leaders in Software Art (LISA), a salon-based collective of artists and technologists founded by Isabelle Draves in 2009. Aesthetic theories of passive interaction allow for media forms that admit viewers have some degree of influence over the story presented, while acknowledging that, ultimately, that story may continue autonomously through decisions made through computation [2]. In this way, the design and installation of I’ll Be Fine echoes the experience of encountering and reacting to an anecdotal story overheard in passing. The story presents three narrators, each in control of his or her own screen, each addressing the viewer through the device of a three-layered cinematic field of background, middle ground, and foreground. Although these compositional layers can assume a number of connotations in the mind of the viewer, I’ll Be Fine attempts to model the personal address of these characters and generally follows the familiar cinematic tradition of placing narrative information on screen in a hierarchical spatial arrangement [3]. As shown in Figure 1, this appropriation of a scheme of deep focus, about-to-be-forgotten or soon-to-be-important elements appear in the background plane, currently influential story elements in the middle ground, and focal elements in the foreground. A traditional reading of foreground, middle ground, and background is not so much challenged in this project, as relied on to provide some aspect of readability for viewers encountering a playable story [4].

Figure 1.

Compositional Planes.

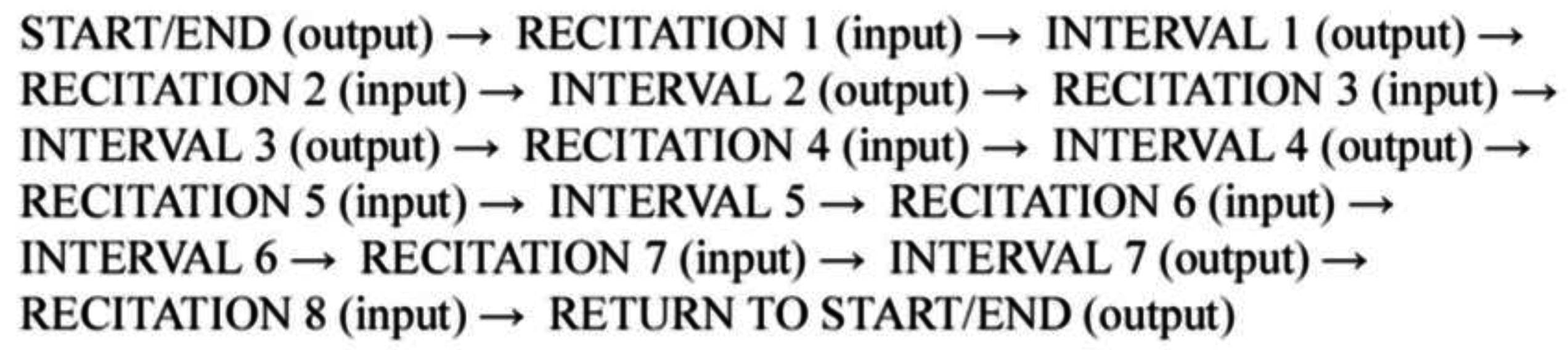

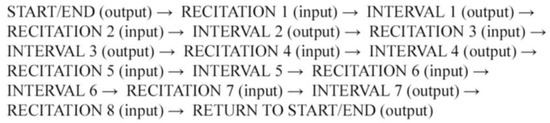

The movie is designed to loop endlessly through sixteen segments as shown in Figure 2: a start/end segment, eight recitations, and seven intervals. At the beginning, intervals, and end of the movie, characters present elements important to their current-state view of the breakup. This part of the movie is made up of visual patterns, graphic icons, and short fragments of text. The effect should be a kind of visual and textual assault, with individual stories feeling unintelligible and resisting assimilation. Starting and ending states for each of the characters feel somewhat alike or bound in a kind of stasis. Each of the characters’ uses text and image to express change and transition during the seven interval segments with certain text fragments and graphic icons moving from plane to plane and even passing from screen to screen, or person to person, as this type of spatial design would suggest.

Figure 2.

Narrative path.

In an intercut, interlocking style, each of the characters uses one of the three screens to work through his or her individual sentiments concerning this romantic breakup. Each presents his or her own version of the event and aftermath, questions, misgivings, regrets, and plans for the future. Each of the characters presents their current-state view of events in the first person, with complete authority, ignoring the feelings, observations, and viewpoints shown on the screens around them. While one screen advances, the other screens continue unchanging in their last left computed state. Their next computed state, however, takes into account any transitions occurring in the active screen during their dormant phases. During recitations, control of the story passes from one screen to another, with cuts and intercuts decided algorithmically, based on inputs from a sensed audience of viewers. Inputs sensed as movements from the audience can also affect the selection and placement of story elements during the recitation segments, placements which in turn affect the narrative path or focus of the interval segments.

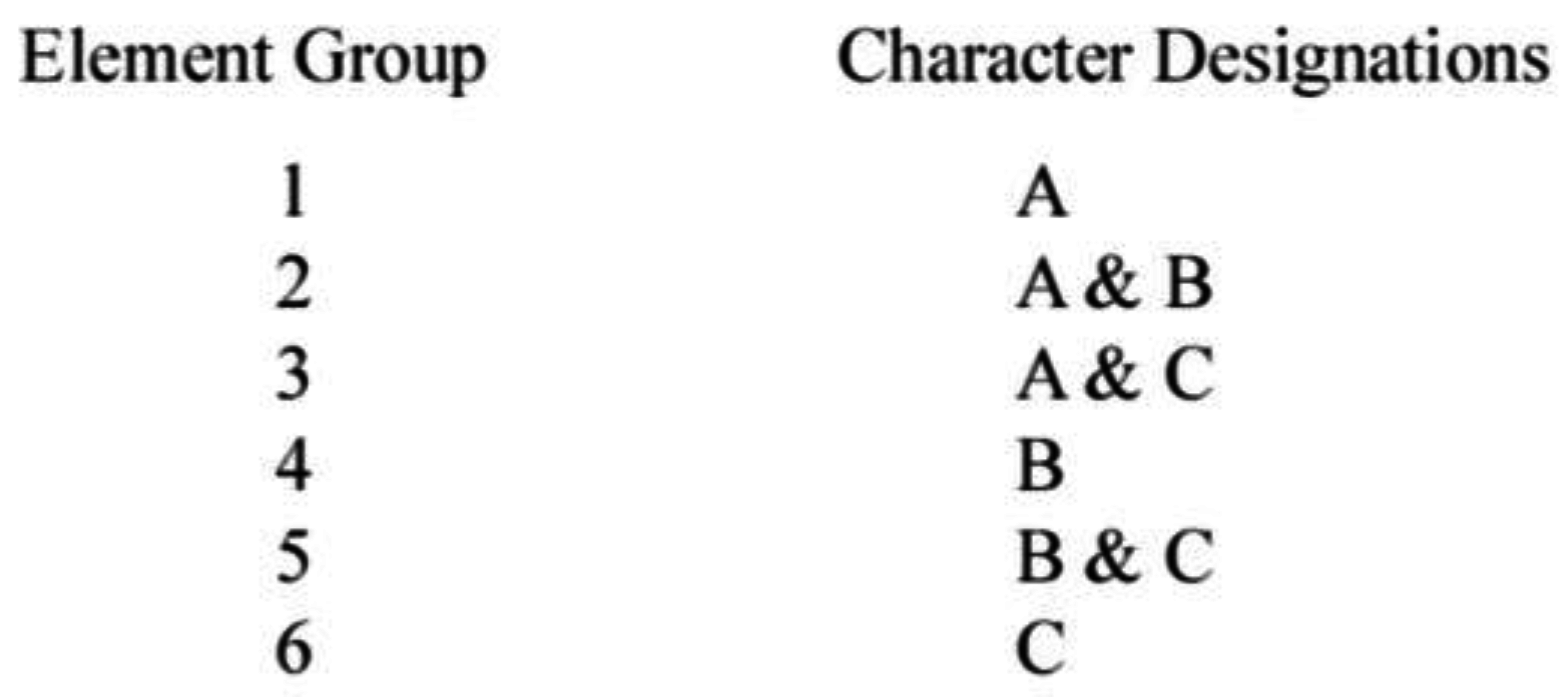

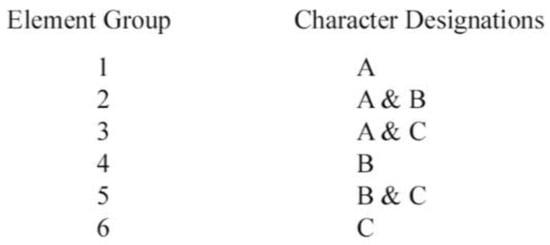

In addition to the structuring effects of screens and compositional layers within those screens, the text fragments and graphic elements of I’ll Be Fine are bound to specific characters or to the idea of the relationship between those characters. Figure 3 shows the plan for distributing these screen visual across the three character screens. Under certain computational rules, a graphic or text element is allowed to pass from one compositional plane to another within a single screen. Under a set of related correlative rules, these elements are also allowed to pass from one screen to another.

Figure 3.

Element categories.

The only universal view of the event would be on the part of a viewer who might step back from an individual screen a attempting to take in all three screens at once in a kind of outside perspective on the story, but there is no global set of story elements, no one correct view of the event.

My intentions for the creation of meaning in I’ll Be Fine would be the result of the aggregate content of the screens, but my plan was that this meaning would also be dependent on the spatial arrangements and movement of that content, the flow of elements through each of the segments (sequence), the transition of story elements from one screen to another, the placement of story elements within the compositional or cinematic planes of background, middle ground, and foreground and, like the shift of elements from one screen to another, the shift of elements from one narrative plane to another. This case study is an attempt to articulate the ideas I had while I was designing these types of spatial arrangements and how I intended those design concepts might help narration metaphorically and allegorically.

2. Structural and Procedural Considerations

The construction of I’ll Be Fine was informed by three primary narrative features: modularity, spatiality and playability.

Spread across three screens, and within those screens across multiple planes, and relying on story elements that were fragmented and combinatory, I’ll Be Fine was conceived of as a modular text, and relies on many of the techniques of modular fiction:

- -

- an effaced or reduced forward-moving plot;

- -

- resistance to any narrative dominance that would imply a central truth or final resolution to the concerns presented in the story;

- -

- a structure that allows for multiple points of view, contradictions, instabilities, and double meanings;

- -

- juxtaposition, flashback, and variation reveal character rather than organize plot;

- -

- disruptions to any linear progressions;

- -

- inclusion of seemingly random events;

- -

- amplification and meaning gained through an accumulation of elements;

- -

- pattern and repetition have privilege over event or plot [5].

The arrangement of story elements in I’ll Be Fine is also intended to be narrative. As with any movie, the use of graphic space in this story is an inseparable part of meaning. Working in multiple directions simultaneously, certain parts of the story are inferred from placements of story elements on screen so that some elements of each story repeat, migrate, interweave, disrupt, or collide with others. A phone number or lipstick case may appear on multiple screens simultaneously, implying a connection the text of the story seems to negate. In other cases, certain themes establish themselves through spatial patterning. For example, self-doubt is symbolized by a rolling bar which may move from plane to plane as thoughts come forward, are evaluated, and dismissed. Romantic expectation is signified by a grid of rotating flowers. Moving elements back and forth in stacks or graphic planes creates correlations and disjunctions between themes and character that are intended to be important aspects of storytelling.

Sequence produces another set of correlations between story elements, but these connections are primarily established through cue or duration. Unlike sequential linkages, spatial connections can be established even when there are contradictions in time, place, or other aspects of a story. For example, once a text associates flowers with a remembered past event, placing flowers in the foreground of one character panel might imply that the character in question is actively recalling a past event. Meanwhile, placing those same flowers in the background of another character’s panel might signal that, for this second character, the past is slipping away.

3. Interaction

As a given in this design, I worked from the idea that, unlike its static fictional counterpart, a playable narrative should be able to distinguish itself by its ability to model some of the processes that justify its existence, and even offer an algorithmic, although fictive, model of those processes. In the case of this specific project, the idea was that as an interactive and playable text, processes interior to the story’s characters could be presented dynamically as a prominent aspect to the viewer’s experience. While watching I’ll Be Fine, viewers do not input into the system intentionally, but passively through their proximity to the screens. Rather than make explicit choices, viewers exert influence, redirecting and refocusing the story by moving through the installation space, or by encouraging a specific screen simply by spending more time in front of it. Since the movie exists in public space, with many possible interactors, and a single viewer cannot be proved to have definitive control over a response from the system, it would be difficult to ascribe intent to any single input to the system. For this reason, viewer interaction with I’ll be Fine is considered passive, but still influential for the text. User inputs in this story act primarily as catalysts for computation. Users do not make choices per se, but feed the narrative impulse of the characters by rewarding those characters with their attention. User input then partially accounts for each character’s interpretation of his or her surroundings, and should also account for the ways I’ll Be Fine establishes and follows narrative paths, chooses among alternate paths, and suppresses other options.

The passive position of the user in this kind of interactive narrative was partly determined by the decision to design a story for public space, where interaction is, by definition, a one-to-many relationship. However, there are also some narrative aspects to passive interaction that worked well with the subject matter. The relationship of viewers to the screens was intended to suggest the typical viewpoint of “witness to an event” rather than “participant in an event” that might describe the situation of an observer to a failed romance. The use of passive rather than active interaction is also consistent with the movie’s interface, spatial relations, visual and textual elements in that it allows viewers to understand I’ll Be Fine as a combinatorial field of its elements. We see the work as a dynamic system, rather than as a narrative organized sequentially in segments (beginning, middle, and end). In other words, as one aspect of its playability, I’ll Be Fine was designed as an ongoing dynamic field, rather than a formal system that seeks goals, end-states, or outcomes.

4. Construction of a Fictional Space

Just as an emotional event lives on in the minds of those who experienced it, the story elements comprising I’ll Be Fine were designed to surface in each character’s awareness over and over again. Characters move from thought to thought, question to question, sorting and resorting actions that led to the end. In a simple spatial scheme, the story occupies three planes within each character screen: background, middle ground and foreground. Each of these planes represents the focal distance of any particular story element from the mind and emotions of the character in question. The background plane is where the story algorithm places elements most distant from the characters’ current account of the experience, the foreground plane is where active thoughts, statements and occupations are displayed. A viewer’s presence near a screen increases the computational activity within that screen, which in turn will affect the influence that character has on the others and the activity in their screens. By moving story elements, words, and text from one plane to another, I’ll Be Fine simulates a character’s active exploration of his or her feelings surrounding a central dramatic event. Passing a story element from one character screen to another, no matter what plane, foreground, middle ground, and background, is involved, can be interpreted as an observation, belief, or conclusion held in common by those same characters. While tracking the movements of story elements from background to foreground and from screen to screen, viewers can follow and build an interpretation of the stories put forward by the characters.

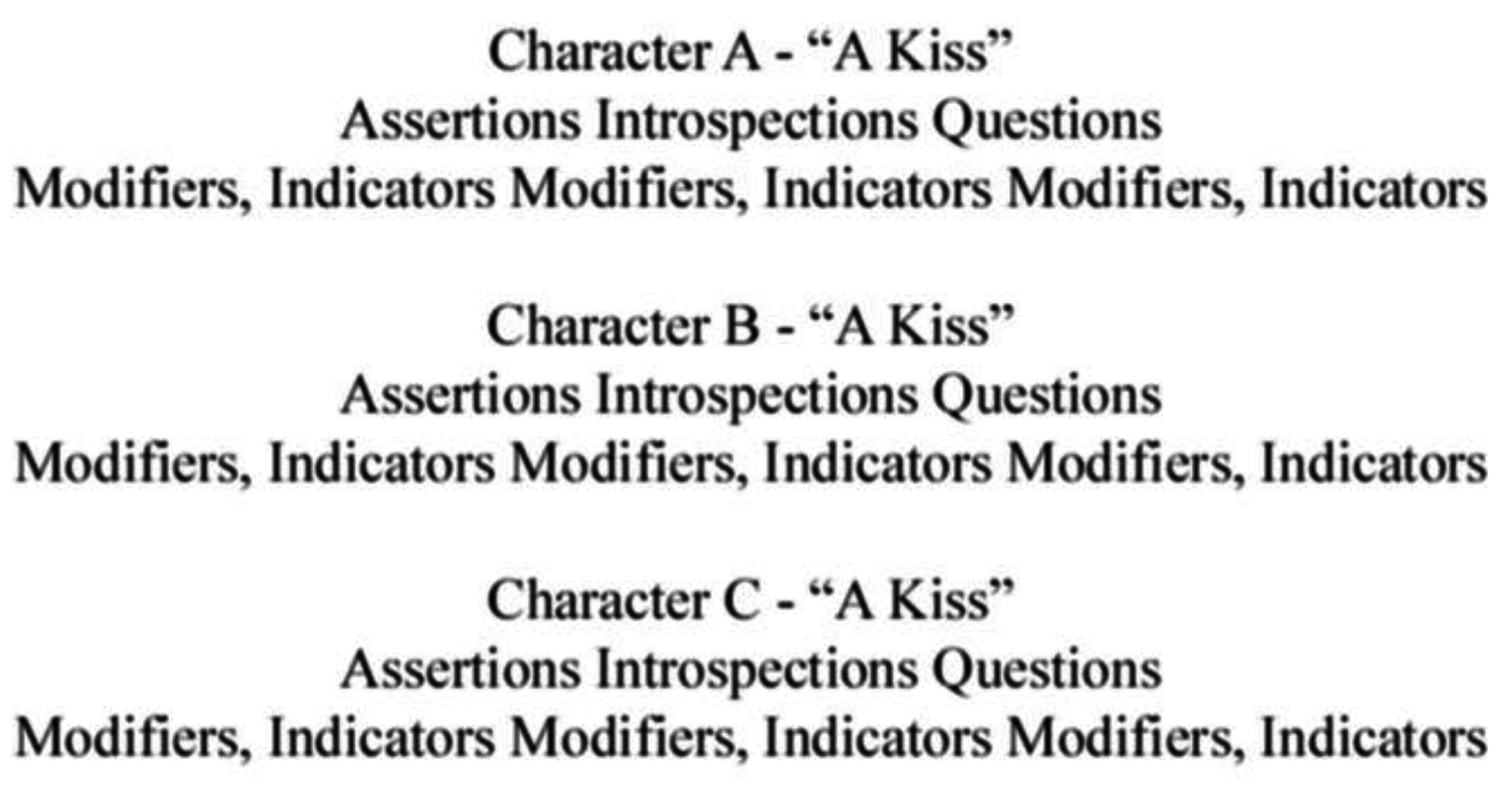

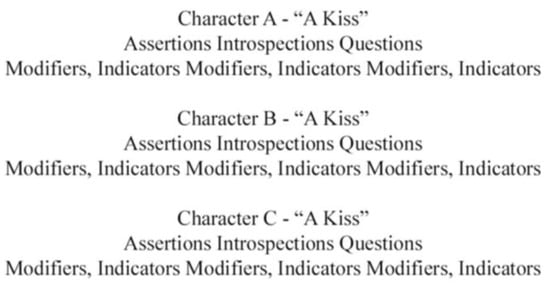

Although Aristotle’s six elements of drama (Spectacle, Character, Fable, Diction, Melody and Thought) remain essential to the construction of contemporary cinema, the narrative modes of I’ll Be Fine follow no Aristotelian logic of connection, hierarchy, or cause and effect, but are sequenced according to computation [6]. There are five modes, or event zones, in I’ll Be Fine. These were organized according to the plan shown in Figure 4. Since this is the story of a breakup, the five events, chosen for their archetypical qualities, are: he/she kissed me, now I remember/now that makes sense, I saw him/her, a fight broke out, am I supposed to wait? Within those five modes there are three types of story element: Assertions, Introspections, and Questions. An assertion is a character’s plain statement of fact or belief: “She was late” or “I never believed Tom”. Introspections are a guess at another character’s state of mind or motivation: “She wanted me to worry” or “She was trying to impress Fred”. Questions are about anything in any mode: “Maybe she planned to be late?” or “I wonder how he felt about Harry?” Within each event mode there are, in addition to the three types of story elements, two classes of statement: modifiers and indicators. Modifiers are graphics or texts that amplify, reduce, suppress, or in some way transform a story element by occupying its foreground plane. Indicators are informational elements that establish identity, time, location and any other details a character might use to fix an emotion in their reality.

Figure 4.

Narrative elements.

As for specific story elements themselves, while their respective identities fundamentally determine the story and its tone, their structural arrangement is by now familiar. Each story element can be viewed as a piece of a closed universe of possibilities, a member of the set of all elements pertaining to this story. These elements, organized in motifs, are distinct instances of narrative fragments within a dynamic system as opposed to a single series of narrative fragments arranged in a pre-determined order. As with their spatial arrangements, their overall ability to be organized dynamically is fundamental to the fictional world.

Computation directs how fragments and elements, and their respective relationships to each other appear. The longer a viewer remains within a screen’s tracking plane, the more ”attention” a character ”feels”, the more rapidly he or she may transform introspection into assertion, etc. The more this first character asserts, the more other characters may resist—or agree—depending on where these assertions land in the second character’s own computational cycle and in the narrative mode of the story state at that given moment.

When I describe the story as spatial, I mean there is a connection between the graphic placement of elements of the story in space and on screens and the meaning of those elements in the fictional world and that this connection has narrative meaning. This is not the same as a correspondence between the spatial patterns of presentation and space as it might be imagined in the story world. In the case of I’ll Be Fine, the story world is concerned with a particular moment in time. The space of the story world is almost completely constrained and the spatial patterns of the movie have no correlation to where events take place in the fictional world. Elements in the story are placed in relation to their psychological and emotional importance to the characters.

Also, characters in this story can only produce meaning by putting forward, combining, and recombining pre-determined units of story elements. The movement of those elements within and across character screens represents the action level of the story. The discourse of the story is composed of the selection of story elements, the spatial organization of these elements, the computational model by which a current story state is produced, and the effect the current computational state produces on the next state of the story. It is not so much that a story is given and a story received, but that a story is calculated, presented, influenced, recalculated, and then re-presented over again [7,8].

5. Construction of a Playable Space

Still, the aim of I’ll Be Fine is not an arrangement of visual and texts, but a worthwhile fictional experience, one that affects viewers with a story of romantic disappointment. What was sought was a form of cinematic expression in which characters make assertions yet continually undercuts themselves, a kind of self-canceling personal account. The spatial juxtaposition of story elements, narrative routines of the self, of personal delusion, blame, regret, dissemblance, and their procedural representation through parataxis, disjuncture, faulty logic, and impulse are in many ways expressive of that fictional situation. Viewers should find themselves confronted with contradictory versions of the same event simultaneously. False conclusions, misunderstandings, poorly grasped intentions all make their way to the screen, leaving observers to sift through multiple, equally weighted accountings in hopes of a final, valid version of what happened. By arranging elements spatially, by subsequently imparting meaning to these spatial relationships as they occur, and by noting how those meanings might change as the story develops, the viewer should be to able to follow, interpret, and empathize, not only with the story as presented by each character, but also with the story as it might impress an outsider, or voyeur, as an interdependent whole. The concept behind this interactive design, was meant to imply that action in the story might be inferred from appearance, placement, and movement through and across the story space, and to continually push the viewer further and further into an interpretive stance.

Viewed this way, the process of placement, which is influenced by the sensed presence of an auditor, becomes a discursive ingredient. An algorithm will ultimately choose where each element is placed, at what frequency, and in what order that element appears; yet that algorithm is to some degree constructed by a viewer’s influence on the activity of a particular screen at a particular moment. The narrative is composed of elements arranged in a collection, organized by motif, triggered by the presence of a viewer, and constructed by the computation that places elements on a particular plane or within a particular screen, but much of the meaning of the piece is a feature of the movie’s arrangement in space and of the interpretative situations that this arrangement makes possible.

Multiple screens are important to the movie as they prevent a single authoritative or official view of the situation, but multiple screens also ask the viewer to come up with a navigational strategy for moving through the space of the story. Sequence exists in time, but an equally important narrative quality is intended to be constructed spatially, spread through and across all of the planes and surfaces presented. Viewers are asked to observe both aspects of the movie at once, by reading planes of narration within screens and the relationships being formed and dissolved between the elements on other screens. Since the movie also exists in sequence, one image following another, one way to think of this structure is as a story that has both a chronology and a topology. This dual nature is intended whether the viewer reads the screens chronologically by focusing on one screen, or reads topographically by taking in all screens at once in a kind of moving image field, or even alternates between two viewing strategies by moving back and forth between screens or between the planes of a single screen.

Allowing that placement and movement of story elements is in this movie is the more determinant aspect of the story’s narrative should mean that we can call the structure of I’ll Be Fine spatial. Unlike sequential narratives, spatial narrative is not primarily concerned with sequential events, or causation. Interaction modes, such as a game model, or any interactive model which privileges sequence or the syntagmatic, are less useful as paratactic or paradigmatic schemes of shaping association. Likewise, in the instance of this movie, ideas of story versus discourse, satellites, or kernels are less useful than ideas about correlation, association and accumulation.

Finally, I would note that - while the spatial arrangement of the story and its means of navigation give some narrative influence to the audience, and to the performance of a viewer, that influence does not in any way relinquish control over the narrative world to the viewer. That world by definition remains a closed world constructed by a writer. Although its identity is one of a system made up of narrative elements in which the relationships between elements is determined computationally, both the data and functional aspects of the story are predetermined. The representational concepts of playable media allow for variation and exploration on the part of viewers and are necessarily organized and re-organized through play and interaction, but their meaning is not dependent, Rather than produce results, playable stories offer an authored, closed model plan, a fictive idea, that through its organization and the discovery of that organization offer insights, experiences, and meaning to the viewer. In these important ways, this type of media is a fictional construction.

6. Analysis of the Structure

A further aspect of story in I’ll Be Fine is carried by the relationships between the assertions, introspections and questions of three fictional characters as they relate the event of their romantic breakup. Those elements are grouped internally, by character, according to motif, and at the same time sequenced and ordered according to more traditional narrative schemes. Just as flowers can represent a happy event in the past, an event that is either being called to mind, or pushed away, birds might symbolize hope for the future, or an impulse to transcend sadder emotions. These categories can thus intermingle, overlap, foreshadow, and even echo each other. We can think of these visual motifs as organizing schemes, one kind of order at work in this fictional world. Viewers are intended by both the design of the interaction scheme and by the structure of the story to follow and track this aspect of narrative.

Viewers are also intended to note the fictional effects created by the movement of story elements from foreground to background. The distance, juxtaposition, dominance and relationships between these aspects of the movie can change at any time, with some parts of the story moving closer, moving apart, or appearing more or less frequently, their spatial placement changing as their relationships in the story change. The placement of story elements on visual planes, and the patterns created from those placements, is intended to create narrative associations that reinforce, contradict, advance, regress, elaborate, correlate, or in some way alter our understanding of the story. Viewers can think of this as the vertical structure of the story.

Yet viewers can also think of this movie as a story unfolding in a series of elements presented in juxtaposition to one another. This is the aspect of the story that appears when the movie is viewed across all screens simultaneously, a juxtaposition that can be thought of as the horizontal structure of the movie world. Here also, the spatial design of the story is somewhat pre-determined, a pre-defined structure or container in which the placement of pre-authored elements—and the fixed possibilities of that placement—implies a kind of fictional information.

Due to the computational nature of their placement and the overall scheme of montage, it would be difficult to determine certain qualities of the story before playing it, such as which narrative patterns or motifs are dominant, which most urgent, which regressive, for these patterns are not dependent on any static feature of the story’s construction and in fact require the presence of the viewer and the viewer’s input as “interactor” to present or reveal themselves fictionally. One way to think of these shifting narrative relationships is to imagine this dynamic aspect of the movie as the modal or real-time structure of the story. Although the spatial location of each character’s point of view is fixed, bound to a single screen, at nearly every point in the movie, most story elements are in motion within the planes of a single screen, possibly within the planes of multiple screens, with a number of elements able to cross screens as the movie plays. This allows a number of story elements to be interpreted in terms of motion and movement through the spatial configuration of the narrative. As the story establishes itself in the imagination of the viewer, the placement of story elements in the background, middle ground, or foreground of a character screen is intended to carry fictional meaning, and the movement of story elements from one plane to another, or one character screen to another, carries narrative meaning. The intention is that the spatial arrangement of story elements becomes an important fictional device and, in a spatial work like this one, those placements become, in a practical sense, an aspect of content [9].

These three aspects of structure—vertical, horizontal and modal—exist simultaneously as a means of expressing fictional experience. For the story to exist, it requires an author, a viewer, and a state of computation.

7. Playability and the Production of Meaning

I’ll Be Fine was also intended to encourage play and playability. A complete experience of the story is tied to the viewer’s willingness to affect a series of associations and spatial placements possible from the story system and the set of story elements provided as content, as well as the interpretive positions the viewer is encouraged to inhabit as the story unfolds. Even in their passive role, viewers are sensed by the system and have the opportunity to adopt a ludic stance in relation to the story. The relevance of the story structure depends on play to reveal itself.

In this sense, I’ll Be Fine is as much a map or simulation as a narrative. There is no resolution to the storyline, just a continual reconfiguration, one that emphasizes and effaces certain aspects of an accounting, with those stresses and easings presented as narrative features of each play or performance of the story. The movie’s interpretive and symbolic possibilities hopefully outweigh the importance of plot, suspense or sequence. The creative fulfillment of the story should lie in an engagement with its fictional presence and with the realization that narrative closure is less important, or even unimportant altogether. What outweighs resolution is the movie’s ability to sustain association and interaction, the orchestration of the movie’s elements, and the continual satisfaction of the evolution of the placement of those elements. In this sense, narrative complexity is created from motif, diversity, pattern, and placement and the ways in which specific viewings of the movie modify each other, so that while there may be several collisions among text and visual elements or revisions of interpretations possible given a specific set of story elements, there is no fixed version of events that would act as a global organizer of a “true”’ narrative accounting. In place of hierarchy there is juxtaposition, gapping, parataxis and layering. While the graphic construction of story elements is more or less traditional, and while the story consistently operates through its own visual motifs, there is no conventional development of a central visual image, but rather several shifting centers of symbolism.

This relationship might also be compared to that between fabula, the set of events or assertions put forward as story elements, and sujzet, the narrative arrangement, frequency, focalization, or hierarchy of those elements [10,11]. Here, story elements, like fabula, have some authorial, pre-determined relationship, while the sujzet or their arrangement is a result of the congruence of passive input from the user and a computational scheme processed by a computer though provided by a writer. The final organizational structure of the fictional world is a combination of both schemes imposed on space over time. The fictional effect should be one related to playability, one in which the movement of story elements from plane to plane and screen to screen acts as a spatial materialization and psychological metaphor for the characters and themes gaining prominence at different points in time [12].

Narrative devices that might be important in a structure like this would be inference, framing, resonance, amplification, composition, superimposition, juxtaposition, and correlation. The function of playability and the presentation of narrative spatially should break down traditional aspects of a more sequential form. Since a playable narrative gains engagement over repetitive readings, and since the presence of the story can be continual, the construction of story in this case moves away from narrative closure and towards exploration. The narrative process is one of assemblage, putting ideas together, breaking them apart, then putting them together again though this time in a new configuration, an organizing concept that should be less constraining formally and ideologically, and one that might encourage revisions of narrative priorities.

Another way to evaluate the playability of a story might be to turn to the observations of specific theorists. In his 1961 book, Man, Play, and Games, French literary critic Roger Caillois attempted a definition of the conceptual aspects of play in an effort to link play activities to the production of culture. Caillois’s writings outline four attributes of playful or ludic structures, paraphrased here as competition, chance, mimicry (the work’s ability to foster make-believe and pretend), and ilinx, a term Caillois uses to describe a kind of dizziness invoked by play, one which disrupts reality, and accordingly extends to the idea of immersion [13].

Some of these features are satisfied in I’ll Be Fine. There is chance, or a process of trial-and-error decision-making as the viewer listens to or shifts her presence from screen to screen, but that action on the part of the viewer and the response on the part of the system proceeds without the intention of an outcome; in other words, viewer input is a feature more indicative of the category of informal play, play which proceeds independently of an explicit set of goals. The movie seeks to be playable by continually pressing viewers deeper into content and further into a narrative sequence which, by design, cannot be resolved or reach a conclusion. Likewise, there is not make-believe in the sense that viewers are expected to take on the role of Character A or Character B, but there is hopefully empathy or suspension of belief, a feature we might also describe as a kind of play, but only informally. There is, if the story is successful, immersion. So that while I’ll Be Fine satisfies some of the fundamental categories of play (chance, mimicry, hopefully immersion), and while a viewing of the move might inspire Huizinga’s important idea of a “magic circle”, the activity on the part of the viewer, in comparison to the interaction offered by a game, is somewhat passive, consisting of a tendency of movements through and across content rather than facing a progressive series of challenges or skill-based encounters in hopes of a positive outcome [14].

At the same time, I’ll Be Fine could not really qualify as a game. A game is a very particular, highly structured, and narrow form of interaction, one that depends on goals, planning and outcomes. While I’ll Be Fine offers interactions, and satisfies some of the qualities of play, by design it resists certain important features of games. Here, agency on the part of the viewer is more vague, slightly ambient. There is no competitive aspect to the viewer’s exploration of the story world, not between the viewer and herself, the viewer and other viewers, or the viewer and the system. There is not, in this structure, an interest in a central illustration of a group of rules per se, or in forcing the viewer through a progressive leveling of skills. There is no goal, no way to “win” or “lose” [15,16]. There are no rules a player might follow to advance a position or affect an outcome. The elements of the fictional world are storytelling elements, about storytelling, they are not related to instruction and do not claim to model a real-world system. Instead, the story world exists primarily as a frame for exploration [17]. At no point is the viewer expected to adopt a metaphoric position in relation to the movie, that is, viewers are not expected, as in a game of chess, to act as if the board and pieces are more than bits of wood, but knights and pawns. In this structure, the meaning created by interactivity is meaning related to story.

For these reasons, I would describe this move as an instance of a new genre of media we might describe as “playable”. Viewers are intended to approach this work as a movie. It proceeds through written and chosen content arranged by an author and, while influenced by and dependent on play, this story is not created through interaction, or its players. Meaning is not something uncovered in a win or lose state or at the end of a segment, level or module, but an experience that is revealed throughout. As in any fictional attempt, the playable structure of the movie presents itself and its variations according to an author’s decisions as to what is important to recognize and reward with attention. The reward for a viewer’s engagement is the experience of that engagement, in other words, the story itself. Narrative is not reduced to a series outcomes or an “and then” exposition. The rules are not strictly predictable. The idea that the same action will lead to the same result, that a strategy lurks beneath the surface of a system, is false within this narrative context. The interface of I’ll Be Fine does not rely on the metaphor of “heads-up design”, scoring, leaderboards, health bars, or any game-like visual syntax. Viewers are not encouraged to “de-focus” and “play the board”, but to concentrate on specifics, be able to draw comparisons, to notice variation.

8. Conclusions

These notes describe the framework for a particular story, I’ll Be Fine. They also make an argument that I’ll Be Fine enacts a form of media that can be described as playable. While playable narratives present some of the features and aspects of meaningful interactivity, they are not directed to goals, outcomes or progressions in the traditional understanding of those terms, and are not intended as or meant to be interpreted as games. This playable story allows viewers to influence the arrangement of story elements on screen in such a way that viewers can construct variable meanings from what is experienced. As in all other kinds of fiction, playable narrative insists on the complexity of its own inner world as its reward for engagement.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Anne Balsamo. “The Cultural Work of Public Interactives.” In A Companion to Digital Art. Chichester: Wiley Blackwell, 2016, pp. 330–51. [Google Scholar]

- Katja Kwastek. “Case Studies.” In Aesthetics of Interaction in Digital Art. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2013, pp. 186–93. [Google Scholar]

- Patrick Ogle. “Technological and Aesthetic Influences on the Development of Deep-Focus Cinematography in the United States.” In Movie and Methods. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1985, vol. II, pp. 58–82. [Google Scholar]

- Christopher Beach. A Hidden History of Film Style: Cinematographers, Directors, and the Collaborative Process. Oakland: University of California Press, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- A. Cameron. Modular Narratives in Contemporary Cinema. Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Aristotle. “Poetics.” The Internet Classics Archive. Available online: http://classics.mit.edu/Aristotle/poetics.html (accessed on 24 March 2017).

- Joseph Frank. “Spatial Form in Modern Literature: An Essay in Two Parts.” The Sewanee Review 53 (1945): 221–40. [Google Scholar]

- Joseph Frank. “Spatial Form in Modern Literature: An Essay in Three Parts.” The Sewanee Review 54 (1945): 643–53. [Google Scholar]

- Tzvetan Todorov. “Papers on Language and Literature.” Edwardsville 50 (2014): 381–424. [Google Scholar]

- Lee T. Lemon, Marion J. Reis, Gary Saul Morson, Viktor Shklovskiĭ, Boris Viktorovich Tomashevskiĭ, and Boris Mikhaĭlovich Ėĭkhenbaum. Russian Formalist Criticism: Four Essays. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Maria Pramaggiore, and Tom Wallis. Film: A Critical Introduction. London: Laurence King Publishing, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- David Bordwell. Narration in the Fiction Film. Madison: Routledge, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Roger Caillois, and Meyer Barash. Man, Play and Games. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Johan Huizinga. Homo Ludens: A Study of the Play-Element in Culture. Kettering: Angelico Press, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Chris Crawford. Chris Crawford on Game Design. Indianapolis: New Riders, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Reza Negarestani. “Parasitic Gamer.” Hyperstition. 21 June 2004. Available online: http://hyperstition.abstractdynamics.org/archives/003370.html (accessed on 24 March 2017).

- Miguel Sicart. “Against Procedurality.” Game Studies. 2011. Available online: http://gamestudies.org/1103/articles/sicart_ap (accessed on 21 April 2017).

© 2017 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).